Abstract

Background

Prednisolone/prednisone coadministration with abiraterone may explain abiraterone-related increase in cardiovascular risk. We explored this postulation and glucocorticoid’s association with cardiovascular risk.

Methods

Patients with prostate cancer on androgen deprivation therapy and enzalutamide, or abiraterone with 5 mg (ABI + P5) or 10 mg (ABI + P10) daily total prednisolone/prednisone were followed up for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).

Results

We analyzed 933 patients. ABI + P10, but not enzalutamide, had higher risk of MACE than ABI + P5. Cumulative glucocorticoid dose before enzalutamide/abiraterone initiation was associated with MACE.

Conclusions

Prednisolone/prednisone coadministration with abiraterone likely contributed to abiraterone-related increased cardiovascular risk. Prevalent cumulative glucocorticoid dose was associated with cardiovascular risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Androgen receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSIs) are recommended for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer [1]. However, these agents are associated with increased cardiovascular risks [2]. We previously observed higher cardiovascular risk in abiraterone users than enzalutamide users [3], with abiraterone’s requirement for prednisolone/prednisone coadministration postulated as a cause. This study thus aimed to explore this postulation and the association between glucocorticoid use and cardiovascular risk in these patients.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong—New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee and followed the Declaration of Helsinki.

The data source was described previously [3]. Briefly, we used the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS), a population-based health records database of all patients who attend public hospitals/clinics in Hong Kong. CDARS is linked to the governmental death registry. Both have been used extensively in research [4].

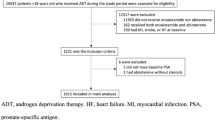

Patients aged ≥18 years old with prostate cancer who received enzalutamide or abiraterone atop androgen deprivation therapy (gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists, and bilateral orchidectomy) in Hong Kong between 1/12/1999 and 31/3/2021 were included. The following patients were excluded: (a) received both drugs simultaneously/separately, (b) with abiraterone initiated without glucocorticoids, (c) with prior stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or heart failure (HF), (d) with enzalutamide initiated with any glucocorticoid, and (e) with abiraterone initiated with any glucocorticoid regimen that is not prednisolone/prednisone 5 mg daily, 5 mg twice daily, nor 10 mg daily. Exclusion criteria (d) and (e) were added to the ones used in our prior study [3] as these prescriptions were not standard for enzalutamide/abiraterone regimens and were likely for other indications.

Patients were followed up from enzalutamide/abiraterone initiation (“index”) until 30/9/2021 or death, whichever earlier. Per our prior study [3], the primary outcome was MACE, a composite of all-cause mortality, MI, HF, and stroke. As some studies suggested efficacy differences between enzalutamide and abiraterone [5], we included an alternatively defined MACE (MACEalternative) as a secondary outcome, defined as a composite of non-PCa-related mortality, MI, HF, and stroke. Outcome and covariate ascertainment have been described in our prior study [3].

The exposure groups (regimen at the start of follow-up) were enzalutamide, abiraterone with 5 mg daily total of prednisolone/prednisone (ABI + P5), and abiraterone with 10 mg daily total of prednisolone/prednisone (ABI + P10).

The association between exposure and the risk of MACE was modeled using multivariable Cox regression, while that for the cumulative incidence of MACEalternative was modelled using multivariable Fine-Gray competing risk regression with PCa-related mortality as the competing event. All regressions were adjusted for pre-specified covariates as listed in Supplementary Table 1. Cumulative glucocorticoid dose at index (CGD) was analyzed as log-transformed prednisolone-equivalent dose (as ln(1 + [cumulative glucocorticoid dose]) to allow transformation of zeros) [6].

In a post-hoc sensitivity analysis, only enzalutamide was compared against ABI + P10, as these groups were more similar in PCa treatment-related covariates (e.g. pre-index ADT duration).

Two-sided p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata v16.1 (StataCorp LLC, United States).

Results

Altogether, 933 patients were analyzed (enzalutamide: 392; ABI + P5: 92; ABI + P10: 449; Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Over a median follow-up of 24.2 (interquartile range: 13.6–41.9) months, MACE occurred in 535 patients (57.3%), whilst MACEalternative occurred in 278 (29.8%).

Compared to ABI + P5, ABI + P10 had higher risks of both MACE (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.90 [95% confidence interval: 1.34–2.68], p < 0.001; Fig. 1A) and MACEalternative (adjusted subhazard ratio [aSHR] 1.53 [1.07–2.17], p = 0.019; Fig. 1B). Meanwhile, enzalutamide did not differ from ABI + P5 for both outcomes (MACE: aHR 1.31 [0.91–1.88], p = 0.144; MACEalternative: aSHR 1.06 [0.79–1.41], p = 0.700). Notably, a higher CGD was associated with higher risks of MACE (aHR 1.10 [1.05–1.16], p < 0.001) and MACEalternative (aSHR 1.06 [1.03–1.10], p < 0.001).

Aalen-Johansen cumulative incidence curves of A major adverse cardiovascular events and B alternatively defined major adverse cardiovascular events, stratified by exposure groups (enzalutamide, abiraterone with 5 mg daily total of prednisolone/prednisone [ABI + P5], and abiraterone with 10 mg daily total of prednisolone/prednisone [ABI + P10]).

In the sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Table 2), enzalutamide had significantly lower risks of MACE and MACEalternative. A higher CGD was associated with higher risks of both outcomes.

Discussion

We observed that ABI + P10 was associated with higher cardiovascular risks than enzalutamide and ABI + P5 (the two of which did not differ significantly in risk) despite enzalutamide users having numerically more comorbidities, and that a higher CGD at index was associated with higher cardiovascular risks. Overall, these findings supported the postulation that prednisolone/prednisone coadministration with abiraterone contributed to abiraterone’s reported increase in cardiovascular risk compared to enzalutamide [3]. This was consistent with a previous study suggesting that high dose glucocorticoid (>10 mg prednisolone/prednisone) was associated with increased MI risk [7]. The lack of significant differences in cardiovascular risk between enzalutamide and ABI + P5 was also consistent with LATITUDE and ARCHES, which found no significant increase in cardiovascular events with abiraterone and enzalutamide, respectively, compared to placebo [8, 9]. It may be prudent for clinicians to carefully consider patients’ CGD and cardiovascular risk before considering ARSIs. Further research should be undertaken to explore glucocorticoid-free abiraterone regimens, with a phase 2 trial suggesting that such regimen may be feasible in selected patients [10].

This study has several limitations. First, there was no data on cancer staging or whether the patients had castration-resistant or hormone-sensitive disease, which may confound the findings. Secondly, this study’s observational nature predisposed to residual confounding and reverse causality. Thirdly, the impact of exposure duration on cardiovascular outcomes was not assessed, which is difficult in observational studies. Randomized controlled trials in this area may be warranted. Lastly, individual data adjudication was not possible; miscoding of events and covariates may, therefore, be possible.

Conclusions

In patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide/abiraterone, prednisolone/prednisone coadministration with abiraterone likely contributed to abiraterone-related increase in cardiovascular risk. A higher prevalent CGD was strongly associated with higher cardiovascular risks.

Data availability

All data underlying this study are available on reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

References

Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II—2020 update: treatment of relapsing and metastatic prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2021;79:263–82.

Iacovelli R, Ciccarese C, Bria E, Romano M, Fantinel E, Bimbatti D, et al. The cardiovascular toxicity of abiraterone and enzalutamide in prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16:e645–e653.

Lee YHA, Hui JMH, Leung CH, Tsang CTW, Hui K, Tang P, et al. Major adverse cardiovascular events of enzalutamide versus abiraterone in prostate cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-023-00757-0.

Wu D, Nam RHK, Leung KSK, Waraich H, Purnomo AF, Chou OHI et al. Population-based clinical studies using routinely collected data in Hong Kong, China: a systematic review of trends and established local practices. Cardiovasc Innov Appl. 2023; 8. https://doi.org/10.15212/CVIA.2023.0073.

Li PY, Lu YH, Chen CY. Comparative effectiveness of abiraterone and enzalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in Taiwan. Front Oncol. 2022;12:822375.

Liu D, Ahmet A, Ward L, Krishnamoorthy P, Mandelcorn ED, Leigh R, et al. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2013;9:30.

Varas-Lorenzo C, Rodriguez LAG, Maguire A, Castellsague J, Perez-Gutthann S. Use of oral corticosteroids and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis. 2007;192:376–83.

Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, Matsubara N, Rodriguez-Antolin A, Alekseev BY, et al. Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N. Engl J Med. 2017;377:352–60.

Armstrong AJ, Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP, Holzbeierlein J, Villers A, Azad A, et al. ARCHES: a randomized, phase III study of androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide or placebo in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2974–86.

McKay RR, Werner L, Jacobus SJ, Jones A, Mostaghel EA, Marck BT, et al. A phase 2 trial of abiraterone acetate without glucocorticoids for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer. 2019;125:524–32.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JSKC conceptualized and designed the study, performed the statistical analyses, visualized the results, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. YHLA and CHL collected and curated the data. DKWL, ECD, KN, GT, and CFN offered expert opinion and supervised the study. All authors revised the manuscript critically and approved its submission and publication in its current form.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

ECD is funded in part through the Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA008748). GT is supported by a Research Impact Fund from Hong Kong Metropolitan University (Project Reference No. RIF/2022/2.2). All other authors have no conflict of interest.

Patient consent

The need for patient consent was waived by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong—New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee due to the retrospective nature of this study and the use of deidentified data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, J.S.K., Lee, Y.H.A., Leung, C.H. et al. Associations between glucocorticoid use and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with prostate cancer receiving antiandrogen: a retrospective cohort study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-024-00889-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-024-00889-x

- Springer Nature Limited