Abstract

Background

Gut microbiota maturation coincides with nervous system development. Cross-sectional data suggest gut microbiota of individuals with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) differs. We hypothesized that infant gut microbiota composition is associated with later ADHD development in our on-going birth cohort study, WHEALS.

Methods

Gut microbiota was profiled using 16S ribosomal RNA and the internal transcribed spacer region 2 (ITS2) sequencing in stool samples from 1 month and 6 months of age. ADHD was defined by parent-reported or medical record doctor diagnosis at age 10.

Results

A total of 314 children had gut microbiota and ADHD data; 59 (18.8%) had ADHD. After covariate adjustment, bacterial phylogenetic diversity (p = 0.017) and bacterial composition (unweighted UniFrac p = 0.006, R2 = 0.9%) at age 6 months were associated with development of ADHD. At 1 month of age, 18 bacterial and 3 fungal OTUs were associated with ADHD development. At 6 months of age, 51 bacterial OTUs were associated with ADHD; 14 of the order Lactobacillales. Three fungal OTUs at 6 months of age were associated with ADHD development.

Conclusions

Infant gut microbiota is associated with ADHD development in pre-adolescents. Further studies replicating these findings and evaluating potential mechanisms of the association are needed.

Impact

-

Cross-sectional studies suggest that the gut microbiota of individuals with and without ADHD differs.

-

We found evidence that the bacterial gut microbiota of infants at 1 month and 6 months of age is associated with ADHD at age 10 years.

-

We also found novel evidence that the fungal gut microbiota in infancy (ages 1 month and 6 months) is associated with ADHD at age 10 years.

-

This study addresses a gap in the literature in providing longitudinal evidence for an association of the infant gut microbiota with later ADHD development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder hallmarked by hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity at a developmentally inappropriate level.1 Studies of the gut-brain axis suggest that the gut microbiome influences neurodevelopment.2,3,4 The gut microbiome develops rapidly over the first 3 years of life concurrently with synaptogenesis, myelination, and synaptic refinement of the central nervous system, and produces a vast range of bioactive metabolites that could influence neurodevelopment.2,5,6,7 Studies of the role of the gut microbiome in neurodevelopment could enhance our understanding of the etiology of neurodevelopmental disorders as well as identify targets for intervention.

Most studies of gut microbiota and ADHD have been relatively small, and cross-sectional, precluding investigation of a temporal relationship. In a study of 19 adolescents and adults with ADHD and 77 healthy controls, ADHD was associated with a higher abundance of Bifidobacterium.8 In a cross-sectional study, children with ADHD had lower levels of Faecalibacterium, Dialister, and Sutterella than controls.9 Children with ADHD had a relatively lower abundance of Bacteroides coprocola and higher abundances of B. uniformis, B. ovatus, and Sutterella stercoricanis in a cross-sectional study of 30 Taiwanese children with ADHD and 30 healthy controls (mean age 8.4 years).10 Finally, in Chinese children aged 6–12 years (17 cases with ADHD and 17 controls), cases had a significantly lower abundance of Faecalibacterium and Veillonellaceae and significantly higher levels of Odoribacter and Enterococcus.11 Less is known, however, about the infant gut microbiome and subsequent risk of childhood ADHD. In a randomized trial of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG supplementation during the first 6 months of life, no supplemented children developed ADHD by age 13 years.12 In this same trial, Bifidobacterium species were lower in children who later developed ADHD.12

Given that neurodevelopment and gut microbiome development are rapid during early life, studies of the association of the infant gut microbiota with neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood are needed. This study sought to examine if early-life gut microbiota composition (at 1 month and 6 months of age) is associated with ADHD in preadolescence.

Methods

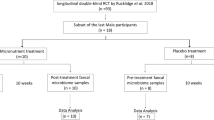

Study population

The Wayne County Health, Environment, Allergy and Asthma Longitudinal Study (WHEALS) recruited pregnant women aged 21–49 years, second trimester or later, with due dates from September 2003 through December 2007, who were seeing a practitioner at any of five clinics in the Henry Ford Health System, and were living in a predefined geographic area that included the city of Detroit and surrounding suburban areas to establish a birth cohort.13,14 Mothers were interviewed in the clinic during pregnancy and postpartum interviewer-administered questionnaires were completed at child age 1, 6, 12, and 24 months. Research clinic visits were conducted at 2 and 10 years of age. Study protocols were approved by the Henry Ford Health System Institutional Review Board. The mother provided written, informed consent at the prenatal visit, and at the age 10 years visit the guardian (primarily the mother) provided written, informed consent, and the child provided written, informed assent.

Definition of ADHD and neurotypical development

At the age 10 years visit, the caregiver reported if the child had ever been diagnosed with ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, Asperger’s syndrome, or sensory processing disorder. Medical chart abstraction was also completed to obtain these diagnoses. We previously reported near-perfect agreement between caregiver-reported and medical record ADHD diagnosis in WHEALS;15 thus, children were considered to have ADHD if either source indicated the child had ADHD. Children were considered neurotypical (NT) if they did not have a caregiver-reported or medical record identified autism spectrum disorder, Asperger’s, ADHD, or sensory processing disorder diagnosis.

Stool specimens

At infant ages 1 and 6 months, stool samples were collected from soiled diapers and stored at −80 °C. Detailed information on DNA extraction methods is presented elsewhere.16

Polymerase chain reaction conditions and library preparation for sequencing

For bacterial sequencing, the V4 region of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene was amplified using Illumina Nextseq (San Diego, CA).17 For fungal sequencing, the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) 2 of the ribosomal RNA gene was amplified using the primer pair fITS7 (5’-GTGARTCATCGAATCTTTG-3’) and ITS4 (5’-TCCTCCGCTTATT GATATGC-3’) and processed using Illumina MiSeq according to previously published protocols.18

Sequence data processing and quality control

Bacterial paired-end sequences were assembled using FLASH v1.2.7 requiring a minimum base pair overlap of 25 bp and demultiplexed by barcode using QIIME (Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology, v1.8). Quality filtering was performed using USEARCH v8.0.1623 to remove reads with >2 expected errors. Quality reads were dereplicated at 100% sequence identity, clustered at 97% sequence identity into operational taxonomic units (OTUs), filtered of chimeric sequences by UCHIME,19 and mapped back to resulting OTUs using UPARSE;20 sequence reads that failed to cluster with a reference sequence were clustered de novo. Taxonomy was assigned to the OTUs using the Greengenes database v13_5.21 Sequences were aligned using PyNAST,22 and FastTree 2.1.323 was used to build a phylogenetic tree. The resulting sequence reads were normalized by multiply rarefying to 60,000 reads per sample as described previously24 to assure reduced data were representative of the fuller data for each sample. The rarefied OTU table was used for all subsequent analyses.

Fungal sequences were quality trimmed (Q score, <25) and removed from adaptor sequences using cutadapt.25 Paired-end sequences were assembled, demultiplexed by barcode, clustered into OTUs at 97% identity and filtered of chimeras using similar methods as described for 16S amplicons. Taxonomy was assigned using UNITE v7.0.26 The resulting sequence reads were normalized by multiply rarefying to 1000 reads per sample to assure reduced data were representative of the fuller data for each sample.

A total of 580 children had at least one stool sample in the final rarefied OTU table; of these, 323 (56%) had data to classify neurodevelopment. We excluded 9 children with autism spectrum disorder, Asperger’s syndrome, or sensory processing disorder. A total of 431 stool samples (229 1-month and 202 6-month) from 314 children had bacterial gut microbiota measured; only 209 of these (107 1-month and 102 6-month) produced an ITS2 amplicon permitting fungal identification.

In the analytical dataset, stool specimens from the 1- and 6-month visits were collected at a mean ± standard deviation of 39 ± 19 and 205 ± 32 days, respectively. Throughout, “1 month” and “6 months” are used as labels of the intended time period of sample collection.

Covariates

During the prenatal interview, the mother self-reported race, date of birth, marital status, household income, education, parity, smoking history, and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Maternal medical records were abstracted to obtain maternal height and weight, prescription antibiotic and antifungal use, delivery mode, birthweight, and gestational age at delivery.27

Statistical analysis

Basic parametric (independent samples t-test and χ2 test) and non-parametric (Fisher’s exact test and Kruskal–Wallis test) tests were used to compare maternal and child characteristics between children with and without ADHD. Linear regression was used to test for the association of alpha diversity metrics (richness, Pielou’s evenness, Faith’s phylogenetic diversity [bacterial only], and Shannon’s diversity) with ADHD. The association of infant gut microbiota composition with ADHD was evaluated using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with the R package vegan (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).28,29 Unweighted and weighted UniFrac were tested for bacterial composition and Canberra and Bray–Curtis for fungal composition.30,31 Because of the small number of children with ADHD and the unbalanced design (large number of NT children), we were concerned about violating the homogeneity of dispersions assumption inherent to PERMANOVA. Homogeneity of dispersion by the group was evaluated using the betadisper function in vegan. Differential abundance of OTUs between ADHD and NT children was tested using zero-inflated negative binomial models (pscl package)32 or negative binomial models (MASS package)33 in cases of non-convergence or model-fitting issues. Only OTUs detected in ≥5% of samples were included for testing. P values were corrected using the false discovery rate;34 false discovery rate corrected p < 0.05 was considered significant. All models were fit unadjusted and adjusted for a pre-specified set of potential confounders (exact age at stool sample collection, maternal body mass index, prenatal antifungal use, maternal smoking during pregnancy, child sex, mode of delivery, gestational age at delivery, parity, and breastfeeding status). Sex-specific effects were tested using interaction terms (interaction p < 0.1 was considered significant).35 For all main effect analyses, p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Among the 314 WHEALS children with gut microbiota and neurodevelopment data, 59 (18.8%) had ADHD. Boys were more likely to develop ADHD (Table 1; p = 0.001). Mothers of children who developed ADHD were more likely during pregnancy to have used antifungals (p = 0.001), to have exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (p = 0.048), to be younger (p = 0.031), and to have a larger body mass index (p = 0.023) (Table 1).

Early-life bacterial and fungal alpha diversity metrics and ADHD

Bacterial alpha diversity metrics in 1-month samples were not associated with ADHD (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1; all p ≥ 0.57). At 6 months of age, both before and after covariate adjustment, Faith’s phylogenetic diversity was higher in children who developed ADHD (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1; both p = 0.017). No other bacterial alpha diversity metrics in 6-month samples were associated with ADHD (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1; all p ≥ 0.17).

Data are mean ± standard deviation. Unadjusted (punadj) and adjusted (padj) p values are presented; adjusted analyses included exact age at stool sample collection, maternal prenatal body mass index, prenatal antifungal use, maternal smoking during pregnancy, child sex, mode of delivery, gestational age at delivery, parity, and breastfeeding status.

Twenty-three (59%) children with ADHD and 84 (44%) NT children had 1-month fungal data (i.e., fungal ITS2 sequences). The fungal amplification rate was not statistically significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.13). Similarly, in 6-month stool samples, 23 (61%) children with ADHD had fungal data compared to 79 (48%) NT children (p = 0.23). Prior to covariate adjustment, fungal richness was higher (p = 0.046) at 6 months of age in children who developed ADHD; after covariate adjustment, this was slightly attenuated and no longer statistically significant (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1; p = 0.083).

Data are mean ± standard deviation. Unadjusted (punadj) and adjusted (padj) p values are presented; adjusted analyses included exact age at stool sample collection, maternal prenatal body mass index, prenatal antifungal use, maternal smoking during pregnancy, child sex, mode of delivery, gestational age at delivery, parity, and breastfeeding status.

The association between all alpha diversity (both bacterial and fungal) metrics and ADHD did not differ by child sex (all interactions p ≥ 0.17).

Early-life gut microbiota compositional differences and ADHD

Bacterial microbiota composition was associated with the development of ADHD (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Bacterial composition at 6 months of age reached statistical significance before covariate adjustment (PERMANOVA; p = 0.012 and p = 0.034, for unweighted and weighted UniFrac, respectively); after covariate adjustment, only the unweighted UniFrac remained statistically significant (PERMANOVA; p = 0.006), explaining 0.9% of the variability. When dispersions of unweighted UniFrac at 6 months were compared between groups, the null hypothesis of homogeneous dispersions was rejected (p = 0.036), with dispersions being smaller in ADHD relative to NT children (average distance to median = 0.38, 0.40, respectively). The association between gut microbiota composition and ADHD did not differ by child sex (all interactions p ≥ 0.12).

Specific bacterial and fungal OTUs at 1 and 6 months of age associated with ADHD development after covariate adjustment are presented in Table 3 (unadjusted results are presented in Supplementary Table 2). At 1 month of age, 18 bacterial OTUs reached statistical significance after covariate adjustment and false discovery rate correction: 6 with lower abundance (including 2 Lachnospiraceae OTUs), and 12 with higher abundance in children who developed ADHD (including Collinsella, Akkermansia, and Dorea OTUs). At 6 months of age, 51 bacterial OTUs reached significance; Enterococcus and Ruminococcus OTUs were relatively depleted in children who developed ADHD, while Dorea and Blautia OTUs were relatively enriched. At the order level, 14 of these 51 OTUs were Lactobacillales (lactic acid bacteria), all but one of which was significantly depleted in children who developed ADHD.

After covariate adjustment, a total of six fungal OTUs were associated with ADHD development, three at each time point (Table 3; unadjusted results are presented in Supplementary Table 2). Specifically, all three significant fungal OTUs at 1 month (Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, Candida orthopsilosis, and Malassezia globose) were in lower abundance in children who developed ADHD. At 6 months of age, two fungal OTUs (one Candida and one Saccharomyces OTU) were in lower abundance in children who developed ADHD while one (Trichosporon OTU) was relatively enriched.

Discussion

Our results indicate that the early-life gut microbiota is associated with ADHD at age 10 years. Specifically, children with ADHD had significantly higher phylogenetic diversity and distinct bacterial compositions at 6 months of age, characterized by a relative depletion of lactic acid bacteria, including Enterococcaceae and Lactobacillales.

Lactic acid bacteria are a diverse group of bacteria characterized by the primary end-product of carbohydrate metabolism being lactic acid36 and impact health through metabolism regulation, defense against infection, and immune activation.37 In a mouse model of dextran sulfate sodium-treated mice, administration of Enterococcus faecalis 2001 reversed neuroinflammation in the hippocampus and depressive symptoms.38 Neuroinflammation is a potential mechanistic factor in ADHD.39 In addition, some Lactobacillus species are capable of producing γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA);40 lower GABA levels are associated with ADHD.41 Thus, the relative depletion of lactic acid bacteria in the gastrointestinal tracts of children at 6 months of age who later developed ADHD could be related to neuroinflammatory effects or reductions in GABA; however, this requires further study.

To our knowledge, no other study has examined the early-life gut microbiome with later development of ADHD, making direct comparisons to other studies difficult. Children with ADHD in the current study had significantly higher bacterial phylogenetic diversity (measured as Faith’s diversity) than NT children at 6 months of age. Previous studies of cross-sectional associations of gut microbiota alpha diversity metrics and ADHD have been mixed; three studies showed no differences in alpha diversity, another showed decreased Shannon diversity, and another study showed higher Shannon diversity and Chao index values, but lower Simpson index values, in children with ADHD compared to controls.8,9,10,11 Diversity in the infant gut increases with age.42 It is possible, although not part of the current analysis, that the association we found between higher bacterial diversity at 6 months of age and ADHD in the current study may actually reflect that children with ADHD experienced precocious gut maturation. Of note, in a study of Bangladeshi infants through age 2 years, two Dorea species were part of the 24 age-discriminant taxa identified;43 Dorea OTUs at both 1 month and 6 months of age were associated with ADHD development in the current study, and thus may suggest that aberrant gut microbiota maturation in early life may influence later ADHD development. Future studies that specifically investigate early maturation of the gut microbiota with neurodevelopment are needed.

Compositionally, previous cross-sectional studies have implicated Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Dialister, Enterococcus, Faecalibacterium, Odoribacter, Sutterella, and Veillonellaceae, as being in differential abundance comparing those with ADHD to healthy controls.8,9,10,11 In the current study, the early-life abundance of Campylobacteraceae, Enterococcaceae, Eubacteriaceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Staphylococcaceae was associated with ADHD in preadolescence. The inconsistent findings across these studies and our own likely relate to the study design (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal) and the timing of gut microbiota measurement (mean age of stool collection ranged from 8 to 27 years, compared to 1 and 6 months of age in the current study).

Several mechanisms by which the gut microbiome could impact neurodevelopment have been postulated, including upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines, altered mitochondrial function, blood–brain barrier or gut permeability changes, and stimulation of afferent vagal nerves by peptides produced by gut microbiota.3 The gut microbiome may also influence available nutrients essential for the developing nervous system.44 Cowan et al. suggested there are critical windows of gut microbiome development that correspond with neurodevelopment.44 In our study, the association of the gut bacterial microbiota with ADHD was more consistent at 6 months of age than 1 month of age, suggesting that exposures in later infancy (e.g., complementary food introduction) may influence or enhance the risk of disease. Further study of the gut microbiota over more frequent time points in early life will be needed to identify specific critical windows of development.

A small body of literature on humans supports the role of the early-life microbiome in various aspects of neurodevelopment, including achievement of developmental milestones and variations in brain structure and function. Sordillo et al. measured the infant gut microbiome (at 3–6 months of age) and the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, 3rd edition, at age 3 years in children participating in the VDAART trial; four bacterial co-abundance groups were identified.45 Clostridiales-dominated co-abundance scores were significantly associated with greater odds of communication skills and personal and social skills delays at 3 years of age whereas Bacteriodetes-dominated co-abundance scores were associated with greater odds of fine motor skills delays.45 Children with ADHD have weaker social skills46 and fine motor control;47 thus, these findings are consistent with an early influence of the gut microbiota on ADHD risk. In a study of 39 1-year olds, higher Faith’s phylogenetic diversity was statistically significantly associated with functional connectivity in several brain regions.48 A number of studies have shown altered functional connectivity between various brain regions in those with and without ADHD.49,50 In a study of 89 healthy children, gut microbiota was measured at age 1 year and the Mullen Scales of Early Learning was administered along with structural brain magnetic resonance imagining at ages 1 and 2 years.51 Higher alpha diversity at age 1 year was associated with an overall lower Mullen cognitive score as well as lower scores on the visual reception and expressive language scales at 2 years of age and with higher brain volumes in the precentral gyrus, left amygdala, and right angular gyrus.51 Children with ADHD have deficits in language, including expressive language.52 Together, these data support the role of the gut microbiota in altering specific aspects of early development and brain structure and function that may precede the diagnosis of ADHD.

Little is known about fungal microbiota and ADHD, with the exception of a case study suggesting that Candida infection worsened ADHD symptoms.53 A challenge in profiling the fungal microbiome is that DNA extraction steps need to be modified due to difficulties with fungal cell lysis.54 Although successful fungal amplification rates were relatively modest in our study despite making such modifications, we did detect fungal OTU differences in children with and without ADHD. Children with ADHD had significant depletion of three fungal OTUs at 1 month (R. mucilaginosa, C. orthopsilosis, and M. globosa) while at age 6 months two fungal OTUs were depleted (a Candida and a Saccharomyces OTU) and one was enriched (Trichosporon OTU.). The relative depletion of some Candida in the early-life gut of children with ADHD was unexpected, given that Candida overgrowth, particularly C. albicans, is associated with other neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder.55,56 Of note, Rhodotorula may strengthen intestinal barrier function and provide a probiotic effect;57 thus, its relative depletion in early life may plausibly influence neurodevelopment. Additional studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Our findings may have implications for the prevention of ADHD beginning in very early life. In a randomized trial, Pärtty et al. found that among children supplemented with L. rhamnosus GG during the first 6 months of life, none developed ADHD by age 13 years.12 However, there is a paucity of randomized trial data on this topic.58 Observational study data, such as ours, may be critical to identify potential targets for intervention. In the current study, we utilized 16S technology to identify potential compositional differences in the early-life gut microbiota of children who later developed ADHD. This does not provide information on the function of these organisms, which may be the best targets for intervention (e.g., production of short-chain fatty acids, metabolism of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids59). Future studies that utilize technologies such as metagenomics, metabolomics, and/or metatranscriptomics59,60 to understand the functional changes in the early-life gut are needed to design potential interventional trials for the prevention of ADHD.

Our definition of ADHD was based on medical record or caregiver-reported doctor diagnosis. While we have previously shown high agreement between medical record and caregiver-reported ADHD diagnosis,15 we do not have data on ADHD subtype (inattentive, hyperactive, or combined), severity, or age at diagnosis, which could be differentially related to microbiota. We were able to adjust for a number of potential confounding factors (e.g., breastfeeding and mode of delivery). Some of these factors, however, may be on the causal pathway, thus models may be over-adjusted.61 ADHD is heritable,62 but we do not have data on the family history of ADHD. It is possible we are missing an important confounding or effect modifying variable. Because we only have antibiotic information in early life on a subset of children, we did not include that as a covariate. In a previous publication of factors impacting early-life microbiota in WHEALS children,16 we failed to detect an association with infant antibiotic use, which was likely due to the small sample size of children with this covariate. While antibiotic use is known to impact gut microbiota, several studies suggest antibiotic use in early life is not associated with ADHD;63,64 thus, it is unlikely that we missed an important confounder in this analysis. However, future studies with more complete data on both prenatal and early-life antibiotic use should examine these relationships further, including a careful investigation by antibiotic timing and class. Although our measurement of the infant gut microbiota at 1 and 6 months of age aligns with the shift from predominantly a facultative anaerobe composition in the first few weeks of life to a strict anaerobe composition at around 6 months of age,65 even with two early-life measurements, we may be missing key time points and inferences about key developmental windows should not be made from our study. However, the current study does provide compelling evidence suggesting the need for future studies with multiple stool sample collection over infancy/early childhood. In their recent review on gut microbiota and ADHD, Checa-Ros et al. noted the considerable differences in associations of the gut microbiota and ADHD across studies;59 we also found some inconsistent findings between our work and previous studies. Previous studies have relied on cross-sectional study designs, and thus alterations in the gut microbiota in those studies could reflect differences due to ADHD treatment, differences in dietary patterns between children with and without ADHD, or reverse causality (changes in the gut microbiota caused by ADHD).66 We found evidence that the assumption of homogenous dispersions was not met. However, for unbalanced designs, PERMANOVA tests are typically too conservative if the larger group has greater dispersion,67 so despite not meeting the homogeneity assumption, results are unlikely to be a false positive.

A strength of the current study is the longitudinal design, with measurement of the gut microbiota preceding ADHD diagnosis by years, and thus differences in the gut microbiota found in our study are not due to ADHD treatment. As described in Checa-Ros et al., future studies with standardized protocols leveraging high-resolution techniques such as shotgun metagenomics are needed to reduce heterogeneity in results across different studies.59

In summary, the early-life gut microbiota is associated with ADHD in preadolescence. Future studies replicating these findings and evaluating potential functional differences are needed.

References

Tarver, J., Daley, D. & Sayal, K. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): an updated review of the essential facts. Child Care Health Dev. 40, 762–774 (2014).

Borre, Y. E. et al. Microbiota and neurodevelopmental windows: implications for brain disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 20, 509–518 (2014).

Principi, N. & Esposito, S. Gut microbiota and central nervous system development. J. Infect. 73, 536–546 (2016).

McDonald, D. et al. Towards large-cohort comparative studies to define the factors influencing the gut microbial community structure of ASD patients. Micro. Ecol. Health Dis. 26, 26555 (2015).

Gilbert, J. A. et al. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat. Med. 24, 392–400 (2018).

Ly, V. et al. Elimination diets’ efficacy and mechanisms in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 26, 1067–1079 (2017).

Evans, J. M., Morris, L. S. & Marchesi, J. R. The gut microbiome: the role of a virtual organ in the endocrinology of the host. J. Endocrinol. 218, R37–R47 (2013).

Aarts, E. et al. Gut microbiome in ADHD and its relation to neural reward anticipation. PLoS One 12, e0183509 (2017).

Jiang, H. Y. et al. Gut microbiota profiles in treatment-naive children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav. Brain Res. 347, 408–413 (2018).

Wang, L. J. et al. Gut microbiota and dietary patterns in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 29, 287–297 (2020).

Wan, L. et al. Case-control study of the effects of gut microbiota composition on neurotransmitter metabolic pathways in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Front Neurosci. 14, 127 (2020).

Partty, A., Kalliomaki, M., Wacklin, P., Salminen, S. & Isolauri, E. A possible link between early probiotic intervention and the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders later in childhood: a randomized trial. Pediatr. Res. 77, 823–828 (2015).

Havstad, S. et al. Effect of prenatal indoor pet exposure on the trajectory of total IgE levels in early childhood. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 128, 880–885 e884 (2011).

Wegienka, G. et al. Racial disparities in allergic outcomes in African Americans emerge as early as age 2 years. Clin. Exp. Allergy 42, 909–917 (2012).

Cassidy-Bushrow, A. E. et al. Prenatal pet keeping and caregiver-reported attention deficit hyperactivity disorder through preadolescence in a United States birth cohort. BMC Pediatr. 19, 390 (2019).

Levin, A. M. et al. Joint effects of pregnancy, sociocultural, and environmental factors on early life gut microbiome structure and diversity. Sci. Rep. 6, 31775 (2016).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 6, 1621–1624 (2012).

Sitarik, A. R. et al. Fetal and early postnatal lead exposure measured in teeth associates with infant gut microbiota. Environ. Int. 144, 106062 (2020).

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C. & Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200 (2011).

Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998 (2013).

McDonald, D. et al. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 6, 610–618 (2012).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics 26, 266–267 (2010).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1641–1650 (2009).

Fujimura, K. E. et al. Neonatal gut microbiota associates with childhood multisensitized atopy and T cell differentiation. Nat. Med. 22, 1187–1191 (2016).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 3 (2011).

Koljalg, U. et al. Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Mol. Ecol. 22, 5271–5277 (2013).

Wegienka, G. et al. Combined effects of prenatal medication use and delivery type are associated with eczema at age 2 years. Clin. Exp. Allergy 45, 660–668 (2015).

Oksanen, J. et al. 2019 Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.5-6. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan.

Oksanen, J. et al. 2012 Community Ecology Package. R Version 2.0-5. http://cran.r-project.org, http://vegan.r-forge.r-project.org/.

Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8228–8235 (2005).

Legendre, P. & De Cáceres, M. Beta diversity as the variance of community data: dissimilarity coefficients and partitioning. Ecol. Lett. 16, 951–963 (2013).

Zeileis, A., Kleiber, C. & Jackman, S. Regression models for count data in R. J. Stat. Softw. 27, 1–25 (2008).

Venables, W. N. & Ripley, B. D. Modern Applied Statistics with S Plus 4th edn (Springer, New York, 2002).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Selvin, S. Statistical Analysis of Epidemiologic Data 2nd edn (Oxford University Press, New York, 1996).

George, F. et al. Occurrence and dynamism of lactic acid bacteria in distinct ecological niches: a multifaceted functional health perspective. Front Microbiol. 9, 2899 (2018).

Pessione, E. Lactic acid bacteria contribution to gut microbiota complexity: lights and shadows. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2, 86 (2012).

Takahashi, K. et al. Effect of Enterococcus faecalis 2001 on colitis and depressive-like behavior in dextran sulfate sodium-treated mice: involvement of the brain-gut axis. J. Neuroinflammation 16, 201 (2019).

Dunn, G. A., Nigg, J. T. & Sullivan, E. L. Neuroinflammation as a risk factor for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pharm. Biochem Behav. 182, 22–34 (2019).

Yogeswara, I. B. A., Maneerat, S. & Haltrich, D. Glutamate decarboxylase from lactic acid bacteria—a key enzyme in GABA synthesis. Microorganisms 8, 1923 (2020).

Mamiya, P. C., Arnett, A. B. & Stein, M. A. Precision medicine care in ADHD: the case for neural excitation and inhibition. Brain Sci. 11, 91 (2021).

Tanaka, M. & Nakayama, J. Development of the gut microbiota in infancy and its impact on health in later life. Allergol. Int. 66, 515–522 (2017).

Subramanian, S. et al. Persistent gut microbiota immaturity in malnourished Bangladeshi children. Nature 510, 417–421 (2014).

Cowan, C. S. M., Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, J. F. Annual Research Review: Critical windows – the microbiota-gut-brain axis in neurocognitive development. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 61, 353–371 (2020).

Sordillo, J. E. et al. Association of the infant gut microbiome with early childhood neurodevelopmental outcomes: an ancillary study to the VDAART randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e190905 (2019).

Ros, R. & Graziano, P. A. Social functioning in children with or at risk for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 47, 213–235 (2018).

Kaiser, M. L., Schoemaker, M. M., Albaret, J. M. & Geuze, R. H. What is the evidence of impaired motor skills and motor control among children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? Systematic review of the literature. Res Dev. Disabil. 36c, 338–357 (2015).

Gao, W. et al. Gut microbiome and brain functional connectivity in infants-a preliminary study focusing on the amygdala. Psychopharmacol. (Berl.) 236, 1641–1651 (2019).

Castellanos, F. X. & Aoki, Y. Intrinsic functional connectivity in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a science in development. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 1, 253–261 (2016).

Uddin, L. Q., Dajani, D. R., Voorhies, W., Bednarz, H. & Kana, R. K. Progress and roadblocks in the search for brain-based biomarkers of autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 7, e1218 (2017).

Carlson, A. L. et al. Infant gut microbiome associated with cognitive development. Biol. Psychiatry 83, 148–159 (2018).

Korrel, H., Mueller, K. L., Silk, T., Anderson, V. & Sciberras, E. Research Review: Language problems in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder – a systematic meta-analytic review. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 640–654 (2017).

Rucklidge, J. J. Could yeast infections impair recovery from mental illness? A case study using micronutrients and olive leaf extract for the treatment of ADHD and depression. Adv. Mind Body Med. 27, 14–18 (2013).

Forbes, J. D., Bernstein, C. N., Tremlett, H., Van Domselaar, G. & Knox, N. C. A fungal world: could the gut mycobiome be involved in neurological disease? Front Microbiol. 9, 3249 (2018).

Iovene, M. R. et al. Intestinal dysbiosis and yeast isolation in stool of subjects with autism spectrum disorders. Mycopathologia 182, 349–363 (2017).

Strati, F. et al. New evidences on the altered gut microbiota in autism spectrum disorders. Microbiome 5, 24 (2017).

Hof, H. Rhodotorula spp. in the gut – foe or friend? GMS Infect. Dis. 7, Doc02 (2019).

Rianda, D., Agustina, R., Setiawan, E. A. & Manikam, N. R. M. Effect of probiotic supplementation on cognitive function in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomised trials. Benef. Microbes 10, 873–882 (2019).

Checa-Ros, A., Jeréz-Calero, A., Molina-Carballo, A., Campoy, C. & Muñoz-Hoyos, A. Current evidence on the role of the gut microbiome in ADHD pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Nutrients 13, 249 (2021).

Rojo, D. et al. Exploring the human microbiome from multiple perspectives: factors altering its composition and function. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 41, 453–478 (2017).

Schisterman, E. F., Cole, S. R. & Platt, R. W. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 20, 488–495 (2009).

Biederman, J. & Faraone, S. V. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 366, 237–248 (2005).

Hamad, A. F., Alessi-Severini, S., Mahmud, S. M., Brownell, M. & Kuo, I. F. Antibiotic exposure in the first year of life and the risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 188, 1923–1931 (2019).

Axelsson, P. B. et al. Investigating the effects of cesarean delivery and antibiotic use in early childhood on risk of later attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 60, 151–159 (2019).

Jena, A. et al. Gut-brain axis in the early postnatal years of life: a developmental perspective. Front Integr. Neurosci. 14, 44 (2020).

Chou, W. J. et al. Dietary and nutrient status of children with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: a case-control study. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 27, 1325–1331 (2018).

Anderson, M. J. & Walsh, D. C. I. PERMANOVA, ANOSIM, and the Mantel test in the face of heterogeneous dispersions: what null hypothesis are you testing? Ecol. Monogr. 83, 557–574 (2013).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI050681, R01 HL113010, R01 HD082147, and P01 AI089473) and the Fund for Henry Ford Hospital. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, in drafting and/or revising critically the article for important intellectual content; and in the final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.V.L. is a board member and consultant for Siolta Therapeutics Inc. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Parental written informed consent and pre-adolescent written informed assent were obtained for the conduct of the study. Specific patient consent was not required for the current manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cassidy-Bushrow, A.E., Sitarik, A.R., Johnson, C.C. et al. Early-life gut microbiota and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in preadolescents. Pediatr Res 93, 2051–2060 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02051-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02051-6

- Springer Nature America, Inc.

This article is cited by

-

Gamma-aminobutyric acid as a potential postbiotic mediator in the gut–brain axis

npj Science of Food (2024)

-

Development of the gut microbiota in the first 14 years of life and its relations to internalizing and externalizing difficulties and social anxiety during puberty

European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2024)