Abstract

Objectives

Infant Follow Up Programs (IFUPs) provide developmental surveillance for preterm infants after hospital discharge but participation is variable. We hypothesized that infants born to Black mothers, non-English speaking mothers, and mothers who live in “Very Low” Child Opportunity Index (COI) neighborhoods would have decreased odds of IFUP participation.

Study design

There were 477 infants eligible for IFUP between 1/1/2015 and 6/6/2017 from a single large academic Level III NICU. Primary outcome was at least one visit to IFUP. We used multivariable logistic regression to identify factors associated with IFUP participation.

Result

Two hundred infants (41.9%) participated in IFUP. Odds of participation was lower for Black compared to white race (aOR 0.43, p = 0.03), “Very Low” COI compared to “Very High” (aOR 0.39, p = 0.02) and primary non-English speaking (aOR 0.29, p = 0.01).

Conclusion

We identified disparities in IFUP participation. Further study is needed to understand underlying mechanisms to develop targeted interventions for reducing inequities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Racial and ethnic disparities in access to medical care, treatments, and outcomes are a pervasive phenomenon in the U.S. healthcare system. Among neonates, there are significant disparities in infant mortality and neonatal morbidity. The Black infant mortality rate is more than double the white infant mortality rate in the United States and the disparity has been widening over the past decade [1]. Among neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), infants born to Black mothers experience poorer quality treatment and have increased rates of NICU-associated morbidity and mortality compared to infants born to white mothers [2,3,4]. Even within a single NICU, observed variations in treatment and care between white and Black patients may be drivers of ongoing disparities in health and developmental outcomes [5].

Newborns admitted to the NICU are at an increased risk of requiring specialized medical and developmental supports and have increased healthcare utilization after discharge. Newborns discharged from the NICU have a three to four-fold increased risk of hospitalization in the first year of life compared to term infants [6]. Preterm infants, especially those born <28 weeks’ gestation, are at an increased risk of having an abnormal neurologic exam and cognitive, neurosensory, and motor impairments [6,7,8]. Prematurity confers an increased risk for chronic health conditions such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), cardiometabolic diseases, and disordered growth [6, 9]. Importantly, these problems are often not evident at the time of NICU discharge.

Recognizing these increased risks and specialized needs after discharge, the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn recommends that all high-risk infants be referred to Infant Follow Up Programs (IFUPs) after discharge [10]. While the composition of IFUPs vary among centers, all provide specialized periodic assessment, diagnosis, and support for medical, neurodevelopmental, and functional impairments [9, 11]. This specialized follow up is meant to be complementary to, and integrated with, routine child health care maintenance examinations provided by primary care pediatricians, using a multidisciplinary approach focused on the medical and developmental concerns unique to this patient population.

IFUPs are designed to increase screening and referral to neurodevelopmental programs, such as Early Intervention, which are associated with improved IQ, school readiness, functional skills [12], and social development [13, 14]. Studies have found that infants who do not participate, have inconsistent participation in IFUPs, or are lost to follow up tend to have poorer sensorineural, sensorimotor, and cognitive outcomes compared to those with more consistent participation [15, 16].

Despite the importance of IFUPs, only ~50% of eligible infants participate [9, 17]. To better understand the low participation rates, studies have examined both social and biologic factors that may contribute to variable participation in infant follow-up. Studies focusing on biologic infant factors have identified that younger gestational age and lower birthweight, increase likelihood of IFUP participation [9, 17,18,19]. Studies focusing on social factors have found that living in primary English language speaking families [9], two-parent homes [9, 15, 20], having private insurance [18, 21], and increased maternal age [18, 19, 22] are associated with increased rates of follow up, while increased distance from the hospital [18, 21, 22], maternal stress, and substance abuse are associated with lower rates of appropriate follow up [22]. Finally, some studies have also identified racial and ethnic disparities in referral and participation [9, 17,18,19]. However, studies have been limited by small sample sizes, difficult to study populations, and inconsistent findings across studies. For example, while Hintz et al. found that infants with comorbidities had increased odds of IFUP participation, Nehra et al. did not [18, 22].

The community and environment in which a child lives is of paramount importance to their health. This has been demonstrated through multiple studies that have found that exposure to environmental adversity impacts both health outcomes as well as health service utilization [23, 24]. While studies have examined the role of distance from the hospital [18, 21] and zip-code [19] in successful IFUP participation, no studies have examined neighborhood characteristics beyond simple geography to understand health services utilization in this population.

The Child Opportunity Index (COI) is a multidimensional index of “neighborhood-based conditions and resources conducive to healthy child development” [25]. The COI has previously been examined as a source of variation in pediatric health, healthcare utilization, and hospitalization but has never to our knowledge been investigated in relation to health services utilization among preterm infants after NICU discharge [24, 26, 27]. Though the exact mechanism by which this operates is not fully understood, it is likely that the COI measures community-level barriers—or facilitators—to care, including social norms and attitudes about health systems, reliable access to transportation, and employment practices that enable parents to take off work to attend doctor’s visits.

Because of widespread segregation in the United States, an individual’s race or ethnicity and the neighborhood where they live are inextricably linked to each other [28]. While race and ethnicity are non-modifiable risk factors, neighborhoods can be modified through community interventions. Thus, we determined that examining the role of neighborhood could aid in identifying modifiable targets for interventions to improve IFUP participation.

As part of a quality improvement initiative in a single large academic Level III NICU, we examined the role of race and ethnicity, neighborhood opportunity, and other maternal and infant factors on IFUP participation with the intent of identifying potential strategies to improve family engagement and ensure follow-through for high-risk infants after NICU discharge. We utilized social epidemiology and a social-ecological framework to inform our hypothesis that infants born to Black mothers, non-English speaking mothers, and mothers who live in “Very Low” COI neighborhoods would have decreased odds of IFUP participation.

Methods

Study design

Our retrospective cohort study was part of a quality improvement initiative in a single large urban academic Level III NICU located in the second largest birth hospital in Massachusetts. This study was designed to identify targets for quality improvement interventions to improve eligible infant referral and participation in a local IFUP. Eligible infants were defined as having gestational age <32 weeks or birthweights <1500 grams. We included all 477 infants discharged between 1/1/2015 and 6/6/2019 eligible for participation in the IFUP. As this study was part of a quality improvement initiative, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined this study was not human subjects research and did not require IRB approval.

Study setting

In our NICU, parents are informed of the IFUP by their team of providers including neonatal nurse practitioners, physicians, and nurses. At the time of the study, written materials were available to families regarding our IFUP. The IFUP coordinator was not involved with the patient during the NICU admission. Referral is made for infants born at gestational age <32 weeks or with birthweight <1500 grams. Appointments are scheduled prior to discharge home from either our Level III NICU or our affiliated Level II special care nurseries for those infants transferred before discharge. Scheduled appointments are noted in the discharge summary. The first appointment is generally made 2–4 months after discharge. Our IFUP has in-person visits weekly on Mondays. No virtual visits or home-visits were offered during the study period as this was not standard of care at the time. Parking reimbursement is provided to offset transportation costs, but no other transportation assistance is otherwise provided. Visits are scheduled with an interpreter as needed for families identifying that English is not their primary language. At the end of the visit, families receive in person feedback and a brief summary of the report as well as additional developmental resources. Following the visit, reports are sent to the infant’s primary care provider.

Variables

The primary outcome was defined as at least one visit to IFUP, as we were primarily interested in uptake of IFUP services. Furthermore, frequency of IFUP is determined by a combination of medical risks and determined needs, thus we limited our investigation to at least one visit to IFUP. The primary predictor variables were race/ethnicity, defined as maternal self-identified race or ethnicity (categorical) and the COI. The COI, is a publicly available census-tract level composite score derived from 19-neigborhood level indicators, in three domains: (1) Education, (2) Health and Environment, and (3) Social and Economic opportunity (Supplementary Table 1). We utilized the composite COI that divides overall opportunity into quintiles (“Very High”, “High”, Moderate”, “Low”, and “Very Low”). The composite COI is an average of the three domain scores. Each domain score is derived relative to the indicators for other census tracts in the region through the use of Z-scores to allow for comparison of census tracts to regional averages [25].

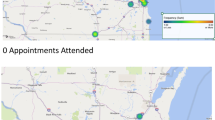

Additional predictor variables included infant factors, maternal social factors, and household social factors. Infant factors included continuous completed weeks and days of gestation, continuous birthweight (grams), dichotomous presence or absence of NICU comorbidity, defined as BPD (need for respiratory support at 36 weeks) or any grade intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), dichotomous need for durable medical equipment (DME) defined as discharge with gastrostomy tube or home oxygen use, dichotomous out-born vs. in-born status, and dichotomous discharge disposition (discharge home vs. transfer to another facility). Maternal social factors included dichotomous primary English language speaking, and dichotomous maternal partner status. Household social factors included continuous Euclidian distance from the IFUP clinic and COI. Distances were calculated using Esri ArcGIS (Redlands, California).

Statistical analysis

We performed bivariate analysis using Student’s t test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables between all variables and the primary outcome. To determine the independent factors associated with IFUP participation, we used multivariable logistic regression using forward selection. We derived the list of candidate variables from bivariate analysis with threshold for inclusion of p < 0.10. We then performed step-wise forward selection using p < 0.05 as threshold for inclusion. We performed step-wise inclusion of all excluded candidate covariables to assess for confounding and collinearity. Confounding was defined by a change in predictor beta coefficient of 10%. All confounders with p value < 0.05 were included in the final model. We included an interaction term to assess our a priori conceptualization that NICU comorbidities act as effect modifiers of the relationship between race/ethnicity and IFUP visit in a separate model. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Code is available upon request.

Results

There were 477 infants eligible for IFUP participation during the study period (Table 1). The average gestational age was 29 weeks and 4 days (standard deviation (SD) 2 weeks and 4 days) with an average birthweight of 1248.6 grams (SD 379 grams). There were 257 male infants and 220 female infants. One hundred fifty-two infants were transferred to another facility prior to discharge and 325 infants were discharged home. One hundred forty-one infants had a NICU comorbidity and 89 infants required DME at the time of discharge.

Racial and ethnic composition was as follows: 196 mothers identified as non-Hispanic white, 66 as non-Hispanic Black, 33 as Asian, and 21 as Hispanic or Latina. One hundred sixty-one mothers identified as either other (82) or their race was unknown (79). Four hundred twenty-two mothers identified English as their primary language. Of the 398 mothers who had marital status documented, 129 were single and 269 were partnered. Average Euclidian distance from the hospital was 22.7 kilometers (km) (SD 20.7 km). Infant COI demographics are as follows: 82 “Very Low”, 84 “Low”, 109 “Moderate”, 108 “High”, and 79 “Very High.”

Of the 477 infants included in the analysis, 200 (41.9%) participated in IFUP (Table 2). Infants who participated were more likely to be of lower gestational age and smaller birthweight compared to those who did not. Additionally, infants who participated were more likely to have a NICU comorbidity, have a need for DME at discharge, and were more likely to be discharged home rather than transferred. COI was significantly associated with IFUP participation. Participants were more likely to have mothers whose primary language was English and be of white race, though these did not reach statistical significance in bivariate comparisons.

From our multivariable logistic regression model, we identified that infants born to Black mothers had a significantly lower likelihood of IFUP participation compared to infants born to white mothers (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 0.43, 95% CI [0.20, 0.90]) (Table 3). Compared to infants whose mothers lived in neighborhoods with “Very High” COI, infants born to mothers living in neighborhoods with “Very Low” COI had significantly lower odds of participation (aOR 0.39, 95% CI [0.17, 0.88]). Finally, maternal primary non-English language speaking was also associated with lower odds of IFUP participation (aOR 0.29, 95% CI [0.12, 0.72]).

In addition to the social predictors of IFUP participation, older gestational age (aOR 0.75, 95% CI [0.68, 0.82]), absence of a NICU comorbidity (aOR 0.48, 95% CI [0.29, 0.80]), and transfer to another facility vs. discharge home (aOR 0.31, 95% CI [0.19, 0.51]) were all significantly predictive of decreased IFUP participation.

We assessed whether NICU comorbidity or COI were effect modifiers of the relationship between race and IFUP participation. That is, does the relationship between race and IFUP participation differ by presence or absence of NICU comorbidity or level of COI. Interaction terms between race/comorbidity and race/COI were added to the model. Neither term was significant suggesting no effect modification.

Discussion

In agreement with our study hypothesis, we identified social factors that contribute to decreased likelihood of IFUP participation. Infants of Black mothers had a 43% decreased odds of participation in clinical follow-up compared to children of white mothers. Infants of mothers whose primary language was not English also had significantly decreased likelihood of participation in IFUP. Additionally, we found that infants of mothers living in neighborhoods with “Very Low” COI compared to “Very High,” regardless of distance from the clinic and independent of race, also had significantly decreased likelihood of participation in IFUP. To our knowledge, this is the first study that investigated the role of neighborhood as a factor contributing to participation in IFUP. These findings highlight the societal contributions to disparities in health services utilization of high-risk infants after NICU discharge.

Our study also identified infant-level factors that contribute to variations in IFUP participation. We found that newborns of younger gestational ages and smaller birthweights had increased odds of participation in IFUP as were those with NICU-associated comorbidities (BPD or IVH). Infants discharged home compared to transferred to another facility before discharge also had increased odds of participation in IFUP. These data are consistent with prior studies that have sought to identify infant-level factors associated with successful IFUP participation [17,18,19, 21, 22].

Our study is unique in that we used an ecologic approach to explore contextual influences on participation in clinical follow-up programs. Specifically, we tested the association of IFUP participation with neighborhood health, environmental, economic, and educational opportunity by utilizing the COI, a metric not previously utilized in this context. Considering drivers of disparities in health services access and utilization at multiple levels, the individual and the neighborhood, highlights the multi-layered and nuanced interactions between children, their families, and their communities and lends insights for making improvements to decrease those disparities.

Infants who participate in IFUP have improved neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes compared to those infants that do not participate or have difficulty participating [15, 16]. Thus, IFUPs are especially important to infants who are at highest risk for long-term sequalae of preterm birth. Prior studies have identified that, compared to infants born to white mothers, preterm infants born to Black mothers have increased rates of NICU comorbidities that are associated with poorer neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes, such as severe IVH [29,30,31]. The racial disparity in IFUP participation we identified suggests that the infants at highest risk for poor outcomes—infants born to Black mothers—are also those that are least likely to participate in IFUP. From a life-course perspective, differential access to, and participation in, recommended post-discharge health services might act to perpetuate or even amplify disparities in NICU-related health outcomes through childhood and early adulthood [32].

Additionally, our study identified that infants born to primary non-English language speaking mothers had a significantly decreased odds of participation in IFUP compared to infants with primary English language speaking mothers. Infants born to primary non-English language speaking mothers have reported decreased satisfaction with their NICU care compared to English speaking families [33]. After discharge, infants born to primary non-English language speaking families have decreased appropriate follow up [33] and have increased emergency department health service utilization [34]. The decreased rate of IFUP participation we identified among infants born to primary non-English language speaking mothers highlights the importance of language and health literacy in ensuring access to appropriate post-discharge health services.

We found that infants born to mothers living in neighborhoods with “Very Low” COI had significantly decreased odds of participation in IFUP compared to infants born to mothers who live in neighborhoods with “Very High” COI. The COI is comprised of 19 indicators across the three domains of Education, Health and Environment, and Social and Economic opportunity (Supplementary Table 1). Neighborhoods with “Very Low” COI are characterized by low average adult educational attainment, low rates of health insurance coverage, high rates of poverty, and proximity to employment [25]. Any one of these factors may contribute to decreased likelihood of IFUP participation. For example, decreased proximity to employment and subsequent long commute times may limit opportunity for convenient clinic appointment times. Finally, low average educational attainment may impact cultural neighborhood norms surrounding healthcare service use. This highlights that drivers of disparities in healthcare utilization have societal, as well as individual, origins and is consistent with the existing literature highlighting system-level characteristics associated with variations in care and outcomes [3, 5, 29, 35].

Interventions to address the disparities in IFUP participation informed by our findings related to COI may include re-locating IFUP clinics from academic centers to community-based sites, having increased flexibility of appointment times to accommodate limitations presented by long commutes, or increased education surrounding the importance and benefit of IFUP. Additionally, our findings may facilitate the development of risk-stratification schemas that incorporate an individual’s neighborhood COI to create targeted interventions to increase the likelihood that individuals in low COI neighborhoods attend IFUP. Further study will be needed to identify the modifiable neighborhood characteristics that contribute to “Very Low” COI and drive variation in IFUP participation in order to create system-level changes that improve population access and participation in IFUPs.

A multilevel approach like Bronfenbrenner’s social-ecological model encourages us to consider the many social contexts that influence child health and development [36]. From the family to the immediate community to the state, region, and nation, each ecological level has resources and constraints, opportunities, and challenges. Furthermore, each level has the capacity to contribute to disparities. Our findings highlight several levels at which disparities in healthcare utilization are propagated: the individual level (gestational age, NICU-associated comorbidities), the family level (maternal race, and primary language), and the societal level (neighborhood COI). Interventions to reduce disparities in IFUP participation should not only be focused on the individual. Instead, a multilevel ecologically based approach must be designed that will both address individual-level factors, such as medical distrust and provider bias, while dismantling systems that promote inequitable healthcare delivery. Novel approaches and changes to the paradigm of care, utilizing quality improvement methodology to ensure equal implementation of interventions across communities, and partnering with communities have been suggested to increase IFUP participation [32].

Informed by the results of this study, we have formally assessed the health literacy environment of our IFUP to address the needs of families with limited English proficiency. Additionally, we have conducted semi-structured interviews with families, staff, and key informants to better understand barriers to participation in IFUP. Finally, we plan to assemble task forces to address our specific findings through the implementation of small tests of change and equity-focused quality improvement methodology [37] to improve IFUP participation.

Our study has several methodologic limitations. First, our study was performed as part of a single center quality improvement initiative with a regionally homogenous sample. Second, our study is limited by a high proportion of mothers who chose to not identify their race or ethnicity. This is likely because collecting data on race is not standardized at the institution level and may be considered highly sensitive. We addressed missingness by conducting sensitivity analyses. In sensitivity analyses, the effect of Black race on IFUP participation did not change when all missing values were set to White. When set to Black, the magnitude of the effect size of Black race was diminished, though the direction of the association was unchanged. It is unlikely that the missing values would take on either extreme given the demographics of our local patient population. Third, our study is limited by the focus on preterm infants. While this is an important population, the high-risk infant population requiring specialized follow up also includes infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, genetic disorders [38], and those requiring surgery [39].

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. First, we a priori sought to identify racial and ethnic disparities associated with IFUP participation and, as noted above, used social epidemiology theory to develop and inform our hypotheses. This provided an epidemiological framework for analysis and a lens for appropriate interpretation of results. Second, by seeking to understand health services utilization among high-risk infants within an ecological framework, our hypotheses and variables, including neighborhood, are meaningfully situated among many levels of influence. This enabled us to establish a foundation for further studies to identify the multilevel, modifiable risk factors that contribute to IFUP participation. Finally, this is the first time, to our knowledge, that neighborhood has been investigated as a contributor to variation and disparity in infant health service utilization. As we begin to understand the multiple levels that contribute to ongoing disparities in neonatal care, it will be necessary to perform large, multicenter, collaborative studies that seek to understand population-level modifiable risk factors as targets for intervention to improve outcomes.

In conclusion, infants born to Black mothers, mothers who did not identify English as their primary language, and those living in neighborhoods with “Very Low” COI were significantly less likely to participate in IFUP. Additionally, younger and smaller newborns, as well as those with NICU comorbidities and those discharged home vs. transferred were more likely to participate in IFUP. Further studies are needed to understand underlying mechanisms and drivers of disparities to be able to develop targeted multilevel interventions to improve IFUP participation among all newborns.

References

Matoba N, Collins JW. Racial disparity in infant mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:354–9. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2017.07.003.

Martin AE, D’Agostino JA, Passarella M, Lorch SA. Racial differences in parental satisfaction with neonatal intensive care unit nursing care. J Perinat. 2016;36:1001–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.142.

Sigurdson K, Mitchell B, Liu J, Morton C, Gould JB, Lee HC, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in neonatal intensive care: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2019:e20183114. https://doi.org/10.1542/PEDS.2018-3114.

Boghossian NS, Geraci M, Lorch SA, Phibbs CS, Edwards EM, Horbar JD. Racial and ethnic differences over time in outcomes of infants born less than 30 weeks’ gestation. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20191106. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1106.

Profit J, Gould JB, Bennett M, Goldstein BA, Draper D, Phibbs CS, et al. Racial/ethnic disparity in NICU quality of care delivery. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20170918. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0918.

Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371:261–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60136-1.

Spittle AJ, Cameron K, Doyle LW, Cheong JL. Motor impairment trends in extremely preterm children: 1991–2005. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20173410. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3410.

Adams-Chapman I, Heyne RJ, DeMauro SB, Duncan AF, Hints SR, Pappas A, et al. Neurodevelopmental impairment among extremely preterm infants in the neonatal research network. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20173091. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3091.

Litt JS, Edwards EM, Lainwala S, Mercier C, Montgomery A, O’Reilly D, et al. Optimizing high-risk infant follow-up in nonresearch-based paradigms. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2020;5:e287. https://doi.org/10.1097/pq9.0000000000000287.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1119–26. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-2174.

Kuppala VS, Tabangin M, Haberman B, Steichen J, Yolton K. Current state of high-risk infant follow-up care in the United States: results of a national survey of academic follow-up programs. J Perinatol. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2011.97.

Litt JS, Glymour MM, Hauser-Cram P, Hehir T, McCormick MC. Early intervention services improve school-age functional outcome among neonatal intensive care unit graduates. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18:468–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.07.01.

Spittle A, Orton J, Anderson PJ, Boyd R, Doyle LW. Early developmental intervention programmes provided post hospital discharge to prevent motor and cognitive impairment in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005495.pub4.

McCormick MC, Brooks-Gunn J, Buka SL, Goldman J, Yu J, Salganik M, et al. Early intervention in low birth weight premature infants: results at 18 years of age for the infant health and development program. Pediatrics. 2006;117:771–80. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-1316.

Callanan C, Doyle L, Rickards A, Kelly E, Ford G, Davis N. Children followed with difficulty: how do they differ? J Paediatr Child Health. 2001;37:152–6. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00621.x.

Tin W, Fritz S, Wariyar U, Hey E. Outcome of very preterm birth: children reviewed with ease at 2 years differ from those followed up with difficulty. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1998;79:F83–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/fn.79.2.F83.

Mercier CE, Dunn MS, Ferrelli KR, Howard DB, Soll RF. Vermont Oxford Network ELBW Infant Follow-Up Study Group. Neurodevelopmental outcome of extremely low birth weight infants from the Vermont Oxford Network: 1998–2003. Neonatology. 2010;97:329–38. https://doi.org/10.1159/000260136.

Hintz SR, Gould JB, Bennett MV, Lu T, Gray EE, Jocson MA, et al. Factors associated with successful first high-risk infant clinic visit for very low birth weight infants in California. J Pediatr. 2019;210:91–8.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.03.007.

Swearingen C, Simpson P, Cabacungan E, Cohen S. Social disparities negatively impact neonatal follow-up clinic attendance of premature infants discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinat. 2020;40:790–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-020-0659-4.

Ballantyne M, Stevens B, Guttmann A, Willan AR, Rosenbaum P. Maternal and infant predictors of attendance at neonatal follow-up programmes. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40:250–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12015.

Harmon SL, Conaway M, Sinkin RA, Blackman JA. Factors associated with neonatal intensive care follow-up appointment compliance. Clin Pediatr. 2013;52:389–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922813477237.

Nehra V, Pici M, Visintainer P, Kase JS. Indicators of compliance for developmental follow-up of infants discharged from a regional NICU. J Perinat Med. 2009;37. https://doi.org/10.1515/JPM.2009.135.

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:245–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8.

Beck AF, Huang B, Wheeler K, Lawson NR, Kahn RS, Riley CL. The Child Opportunity Index and disparities in pediatric asthma hospitalizations across one Ohio metropolitan area, 2011–2013. J Pediatr. 2017;190:200–6.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.08.007.

Acevedo-Garcia D, McArdle N, Hardy EF, Crisan UI, Romano B, Norris D, et al. The child opportunity index: improving collaboration between community development and public health. Health Aff. 2014;33:1948–57. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0679.

Kersten EE, Adler NE, Gottlieb L, Jutte DP, Robinson S, Roundfield K, et al. Neighborhood child opportunity and individual-level pediatric acute care use and diagnoses. Pediatrics. 2018;141. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2309.

Aris IM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Jimenez MP, Li L, Hivert M, Oken E, et al. Neighborhood child opportunity index and adolescent cardiometabolic risk. Pediatrics. 2021;147. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-018903.

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X.

Howell EA, Janevic T, Hebert PL, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J. Differences in morbidity and mortality rates in Black, White, and Hispanic very preterm infants among New York City hospitals. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:269. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4402.

Janevic T, Zeitlin J, Auger N, Egorova NN, Hebert P, Balbierz A, et al. Association of race/ethnicity with very preterm neonatal morbidities. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:1061. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2029.

Murosko D, Passerella M, Lorch S. Racial segregation and intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1508.

Beck AF, Edwards EM, Horbar JD, Howell EA, McCormick MC, Pursley DM. The color of health: how racism, segregation, and inequality affect the health and well-being of preterm infants and their families. Pediatr Res. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0513-6.

Miquel-Verges F, Donohue PK, Boss RD. Discharge of infants from NICU to Latino families with limited English proficiency. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:309–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-010-9355-3.

Abdulla L, McGowan EC, Tucker RJ, Vohr BR. Disparities in preterm infant emergency room utilization and rehospitalization by maternal immigrant status. J Pediatr. 2020;220:27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.01.052.

Horbar JD, Edwards EM, Greenberg LT, Profit J, Draper D, Helkey D, et al. Racial segregation and inequality in the neonatal intensive care unit for very low-birth-weight and very preterm infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173:455. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0241.

Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; 1979.

Reichman V, Brachio SS, Madu CR, Montoya-Williams D, Peña MM. Using rising tides to lift all boats: equity-focused quality improvement as a tool to reduce neonatal health disparities. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.siny.2021.101198.

Wojcik MH, Stewart JE, Waisbren SE, Litt JS. Developmental support for infants with genetic disorders. Pediatrics. 2020;145. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0629.

Laing S, Walker K, Ungerer J, Badawi N, Spence K. Early development of children with major birth defects requiring newborn surgery. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47:140–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01902.x.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Wenyang Mao for her biostatistical support and consultation.

Funding

This work was supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant number T32HS000063. YSF was supported by AHRQ grant number T32HS000063 as part of the Harvard-wide Pediatric Health Services Research Fellowship Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YSF conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. JES and JSL conceptualized and designed the study, designed the collection instruments, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fraiman, Y.S., Stewart, J.E. & Litt, J.S. Race, language, and neighborhood predict high-risk preterm Infant Follow Up Program participation. J Perinatol 42, 217–222 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01188-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01188-2

- Springer Nature America, Inc.

This article is cited by

-

Social determinants of health and language outcomes in preterm infants with public and private insurance

Journal of Perinatology (2024)

-

Disparity drivers, potential solutions, and the role of a health equity dashboard in the neonatal intensive care unit: a qualitative study

Journal of Perinatology (2024)

-

Association between neurodevelopmental outcomes and concomitant presence of NEC and IVH in extremely low birth weight infants

Journal of Perinatology (2024)

-

A mixed methods study of perceptions of bias among neonatal intensive care unit staff

Pediatric Research (2023)