Abstract

Objective

Short interpregnancy interval (IPI) is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth (PTB < 37 weeks GA). We investigated whether short IPI (< 6 months) contributes to the higher PTB frequency among non-Hispanic Blacks (NHB).

Study design

Using a linked birth cohort > 1.5 million California live births, we examined frequencies of short IPI between racial/ethnic groups and estimated risks by multivariable logistic regression for spontaneous PTB. We expanded the study to births 1991–2012 and utilized a “within-mother” approach to permit methodologic inquiry about residual confounding.

Results

NHB women had higher frequency (7.6%) of short IPI than non-Hispanic White (NHW) women (4.4%). Adjusted odds ratios for PTB and short IPI were 1.64 (95% CI 1.54, 1.76) for NHW and 1.49 (1.34, 1.65) for NHB. Using within-mother analysis did not produce substantially different results.

Conclusions

Short IPI is associated with PTB but does not explain risk disparity between NHWs and NHBs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB) is a leading cause of infant morbidity and mortality in the United States [1,2,3], and disproportionately affects some racial minorities [4]. Notably, the occurrence of PTB among non-Hispanic Blacks is substantially greater than among non-Hispanic Whites with frequencies among all births of 13.2% and 8.9%, respectively [5]. Underlying causes for such disparities remain elusive and likely multifaceted. Several studies have observed that non-Hispanic Blacks tend to have greater occurrence of shortened (i.e., < 6 months) interpregnancy interval (IPI, i.e., the time between the end of one pregnancy and conception of the next) than non-Hispanic White women [6,7,8,9].

These observations coupled with findings that short IPI is a risk factor in the overall population for PTB, even when controlled for maternal education, parity, and previous prematurity [7, 10,11,12,13,14,15], motivated us to investigate the risk of PTB at short IPI among non-Hispanic Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites in the population. Specifically, we examined risk of spontaneous PTB among non-Hispanic Black women and non-Hispanic White women based upon various IPIs in California over a 22-year period. Consistent with recent studies [16, 17], we also utilized a “between-mother” and “within-mother” approach to permit methodologic inquiry about the contribution of residual confounding influences to such findings.

Materials and methods

We investigated live births in California between 1991 and 2012 from California linked birth cohort files. These files merge fetal death, birth, and infant death certificates in California with Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development maternal and infant hospital discharge data from pregnancy, at delivery, and up to 1 year after delivery (previously described) [18,19,20]. This work was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board and the California State Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

For our primary analyses of IPI we restricted the overall 1991–2012 study cohort (to allow for standardized gestational age dating, i.e., best obstetrical estimate) to those births in the period 2007–2012. For these, we included linked birth certificate (BC) and maternal and infant hospital discharge summaries for all singleton, live births between 20 and 41 weeks of age gestation for multiparous, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Asian and Hispanic women (n = 1,721,711). Exclusion criteria were missing previous live birth date, live births preceded by a termination, and implausible (< 36 days) IPI (n = 153,776). The majority of exclusion criteria (n = 132,843) was comprised of early pregnancy loss reported between live births. All study variables were derived from the linked files. Gestational age at delivery, in weeks, was based on the obstetric estimate. Variables included maternal age (continuous), parity (2, 3, ≥ 4), prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) (underweight, normal, overweight, obese I, obese II, obese III, missing), educational attainment (some high school or less, high school graduate/equivalent, some college, college graduate or more, missing), medical payment (Medi-Cal, private insurance, self-pay/medically unattended birth, other, missing), initiation of prenatal care (within first 5 months, 6 months or later/no initiation, missing), previous PTB (yes or no), and smoking during pregnancy (yes, no, missing) [18].

PTB was defined as < 37 weeks gestational age and more narrowly as 20–23, 24–31, and 32–36 completed weeks, owing to their suspected underlying etiological differences. PTB was also examined by the clinical subtypes spontaneous, medically indicated, and unclassifiable. First, births < 37 weeks were classified as spontaneous PTB when codes for premature rupture of membranes (PROM; ICD-9 diagnosis (dx): 658.1; BC labor/delivery: 10), premature labor (ICD-9 dx: 644), or tocolysis (BC pregnancy/concurrent illness: 28) were identified. Remaining births < 37 weeks were considered medically indicated PTB if none of the above codes to identify spontaneous PTB were reported, and there was a code for medical induction (ICD-9 procedure (pr): 73.1, .4; BC labor/delivery: 11, 12), artificial rupture of membranes (AROM; ICD-9 pr: 73.0), or cesarean delivery (ICD-9 pr: 74; BC method of delivery: 01, 11, 21, 31, 02, 12, 22, 32). All births < 37 weeks not captured by either above groups were considered unclassifiable.

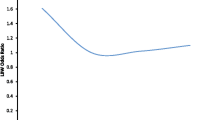

IPI was defined as the interval from previous live birth to conception of the present live birth. IPI was calculated in months from the date of the previous live birth to the date of the present live birth, minus the gestational age, i.e., estimated conception date. Date of previous live birth contained year and month information only and as such was set to the middle of the month for IPI calculations. Recent studies demonstrate that short IPI (< 6 months) and long IPI (≥ 60 months) are associated with increased risk for PTB [18, 21,22,23,24]. We classified IPI as < 6 months, 6–11 months, 12–17 months, 18–23 months (reference range), 24–29 months, 30–35 months, 36–47 months, 48–59 months and ≥ 60 months. The reference range was identified by Zhu et al. [12], noting the lowest risk for perinatal outcomes is an IPI of 18–23 months.

We examined the distribution of IPI as frequency and percent for each race/ethnicity. Multivariable logistic regression models estimated odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all PTB, spontaneous PTB, and medically indicated PTB each at 20–36, 20–23, 24–31, and 32–36 weeks. Models were adjusted for covariates including maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, smoking during pregnancy, education, payer, parity, previous PTB, and prenatal care.

In addition, analyses to investigate potential residual confounding influences, i.e., women with short IPIs may be predisposed to adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth [16, 17, 25, 26], we employed a within-mother analysis. This strategy attempted to account for measured and unmeasured factors inherent to mothers (e.g., genetic predisposition). We assembled a set of mothers who gave birth to their first three consecutive live births in California using the entire study cohort of birth from 1991 to 2012. To examine between versus within-mother risks, we compared results from conditional logistic regression (each mother possesses two distinct IPIs and acts as her own control) with unconditional logistic regression (based on across mother comparisons). Between-mother models adjusted for parity, education, age, year, and previous birth outcome (term, preterm). Within-mother models adjusted for parity, education, age, and year. The birth cohort files link multiple births to the same woman and provide unique maternal IDs. To ensure correct identification of consecutive births to the same mother, we required that the maternal birth date match across records and that the month and year of the preceding birth listed on the second BC matched the month and year of birth recorded on the first BC. In this analysis, our estimate of gestational age at delivery was based on last menstrual period. Exclusion criteria for any of the three births to a single mother were delivery at < 20 or > 44 weeks, undetermined sex, implausible birth weight [27], age < 14, IPI < 36 days, and reported termination in between live births.

Results

In California between 2007 and 2012 there were 385,919 singleton live births to non-Hispanic White women and 86,568 births to non-Hispanic Black women—these two racial/ethnic groups were the focus of analyses. Characteristics of these two groups are shown in Table 1.

Percentages of PTB overall among non-Hispanic Whites and Blacks were 5.86% and 10.56%, respectively. Frequencies of births by the two racial/ethnic groups and by various IPIs are shown in Table 2. Non-Hispanic Blacks had higher prevalence of short IPI (< 6 months) at 7.6%, compared to 4.4% for non-Hispanic Whites.

Risks (odds ratios) of PTB (20–36 weeks gestation) with short IPI (< 6 months) were elevated in both racial/ethnic groups, 1.64 (95% CI 1.54, 1.76) for non-Hispanic Whites and 1.49 (95% CI 1.34, 1.65) for non-Hispanic Blacks. Risks were also elevated for PTB associated with long IPI (≥ 60 months) at 1.35 (95% CI 1.29, 1.43) for non-Hispanic Whites and 1.31 (95% CI 1.20, 1.43) for non-Hispanic Blacks (Table 3a). These elevated risks were also observed for more narrowly defined PTB gestational ages, i.e., 20–23, 24–31, and 32–36 weeks (Table 3a). Similar risk patterns (short and long IPI) were also observed for spontaneous PTB (Table 3b), but risks were substantially lower for comparisons involving medically indicated PTB (see Table 3c, Supplemental materials).

For analyses involving between- and within-mother comparisons, mothers having their first three singleton live births in California between 1991 and 2012 included 126,020 non-Hispanic Whites and 22,946 non-Hispanic Blacks. Compared with the reference IPI of 18–23 months, non-Hispanic Blacks, and non-Hispanic Whites had similar elevated risks for PTB (< 37 weeks gestation) associated with short IPI < 6 months: i.e., non-Hispanic Whites 1.35 (95% CI 1.25–1.46) and non-Hispanic Blacks 1.31 (95% CI 1.16–1.49), but differed somewhat for IPIs of ≥ 120 months, i.e., the risks were 1.31 (95% CI 1.02, 1.67) and 1.67 (95% CI 1.44, 1.94) for non-Hispanic Whites and non-Hispanic Blacks, respectively (Table 4). In comparing between- and within-mother analyses, the risk of PTB for IPI ≤ 6 months was slightly attenuated for non-Hispanic White women but not for non-Hispanic Black women. Long IPIs were attenuated using within-mother analyses for both racial/ethnic groups.

Discussion

In this population-based study of 385,919 singleton live births, short IPI < 6 months was associated with increased spontaneous PTB risk across various gestational ages in both non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White women. These elevated risks tended to be about the same magnitude in both racial/ethnic groups. These elevated risks were also observed in analyses that were conducted utilizing a between-mother and within-mother approach to permit methodologic inquiry about the contribution of residual confounding influences to such findings. Elevated risks of PTB were also observed in both racial/ethnic groups associated with long IPIs, defined as ≥ 60 months.

Racial disparities in adverse pregnancy outcomes have been studied for years [4, 6,7,8, 28,29,30,31,32,33]. Non-Hispanic Black women tend to have higher frequencies of short IPI compared with non-Hispanic White women [6, 7, 33,34,35]. This higher frequency was observed in our study as well with 7.6% and 4.4%, respectively. Contrary to some prior studies [6, 28, 36], but not all [7, 35], non-Hispanic White women had increased risk of PTB compared to non-Hispanic Blacks with the same IPI intervals. The prevalence of PTB among non-Hispanic Blacks with IPI < 6 months in this California population was 1.7 times that for non-Hispanic Whites. As observed in this large population, the overall PTB prevalence among non-Hispanic Blacks was 10.6% and among non-Hispanic Whites was 5.9%. If the frequency of short IPI (< 6 months) in non-Hispanic Blacks (7.6%) had been the same as non-Hispanic Whites (4.4%), this would only reduce the overall PTB prevalence in non-Hispanic Blacks from 10.6% to 10.4% (assuming the referent IPI of 18–23 months experienced a proportional increase). Khoshnood et al. [7] also concluded that short IPI does not explain the magnitude of the disparity between non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White women.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to utilize a within-mother analysis and stratify by race/ethnicity. Similar to others [16, 17], the risk of spontaneous PTB was attenuated at short IPI, indicating that controlling for some factors via within-mother analysis reduces confounding influences that contribute to observed risks for between-mother results. Another study looked at controlling for residual confounding through a within-family analysis, and found short IPI was still associated with increased risk of PTB [37]. In our study, however, PTB risk was attenuated for non-Hispanic White women only and was not substantially attenuated for non-Hispanic Black women. The implication of the latter, i.e., risk was not attenuated for non-Hispanic Black women, has not previously been reported from these administrative data and may serve as a clue to be explored further with more granular data.

A major strength of this study was the size of the population-based cohort. This enabled new comparisons including investigation of finer PTB definitions associated with short (and long) IPI. Within-mother analyses help to control potential effects of unmeasured confounders. There were also limitations of this study. Administrative data lack detailed information on potentially meaningful variables such as whether the pregnancy was planned or unplanned, or if breastfeeding occurred—factors that could contribute to various behaviors (e.g., nutritional intake) between the end of one pregnancy and the beginning of the next. Miscarriage, or early spontaneous termination of pregnancy, is a common pregnancy outcome, reported to occur among 10–25% of recognized pregnancies [38, 39]. The influence, if any, of a prior pregnancy loss < 20 weeks on the outcome of a consecutive pregnancy is uncertain. How best to treat women who report terminations in between pregnancies regarding analysis of IPI is unclear [26]. In this study, women who reported terminations in between live births were removed.

The underlying explanations for the elevated risk of spontaneous PTB among non-Hispanic Blacks continue to elude our best analytic efforts to identify variables of import, including maternal education, smoking, BMI, and social disadvantage [32]. Our a priori expectation was that short IPI among non-Hispanic Blacks—which is more frequent than short IPI for non-Hispanic Whites—would have an associated risk of PTB much larger than observed for non-Hispanic Whites and therefore contribute meaningfully to the overall elevated PTB risk for non-Hispanic Blacks. That combination was not observed here. If we have to reduce the overall population burden of spontaneous PTB, novel approaches will be needed to discern the obviously complicated social and biologic determinants of this condition in various racial/ethnic groups.

References

Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding Premature B, Assuring Healthy O. The National Academies Collection: reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Behrman RE, Butler AS (eds). Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences: Washington (DC), 2007.

Muglia LJ, Katz M. The enigma of spontaneous preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:529–35.

Callaghan WM, MacDorman MF, Rasmussen SA, Qin C, Lackritz EM. The contribution of preterm birth to infant mortality rates in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1566–73.

DeSisto CL, Hirai AH, Collins JW Jr., Rankin KM. Deconstructing a disparity: explaining excess preterm birth among U.S.-born black women. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28:225–30.

Murphy SL, Mathews TJ, Martin JA, Minkovitz CS, Strobino DM. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2013–2014. Pediatrics. 2017;139:pii: e20163239.

Rawlings JS, Rawlings VB, Read JA. Prevalence of low birth weight and preterm delivery in relation to the interval between pregnancies among white and black women. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:69–74.

Khoshnood B, Lee KS, Wall S, Hsieh HL, Mittendorf R. Short interpregnancy intervals and the risk of adverse birth outcomes among five racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:798–805.

Hogue CJ, Menon R, Dunlop AL, Kramer MR. Racial disparities in preterm birth rates and short inter-pregnancy interval: an overview. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:1317–24.

James AT, Bracken MB, Cohen AP, Saftlas A, Lieberman E. Interpregnancy interval and disparity in term small for gestational age births between black and white women. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:109–12.

Smith GC, Pell JP, Dobbie R. Interpregnancy interval and risk of preterm birth and neonatal death: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2003;327:313.

Fuentes-Afflick E, Hessol NA. Interpregnancy interval and the risk of premature infants. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:383–90.

Zhu BP, Rolfs RT, Nangle BE, Horan JM. Effect of the interval between pregnancies on perinatal outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:589–94.

Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295:1809–23.

Ahrens KA, Nelson H, Stidd RL, Moskosky S, Hutcheon JA. Short interpregnancy intervals and adverse perinatal outcomes in high-resource settings: An updated systematic review. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2018;33:O25–O47.

DeFranco EA, Stamilio DM, Boslaugh SE, Gross GA, Muglia LJ. A short interpregnancy interval is a risk factor for preterm birth and its recurrence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:264.e261–6.

Ball SJ, Pereira G, Jacoby P, de Klerk N, Stanley FJ. Re-evaluation of link between interpregnancy interval and adverse birth outcomes: retrospective cohort study matching two intervals per mother. BMJ. 2014;349:g4333.

Hanley GE, Hutcheon JA, Kinniburgh BA, Lee L. Interpregnancy interval and adverse pregnancy outcomes: an analysis of successive pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:408–15.

Shachar BZ, Mayo JA, Lyell DJ, Baer RJ, Jeliffe-Pawlowski LL, Stevenson DK, et al. Interpregnancy interval after live birth or pregnancy termination and estimated risk of preterm birth: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2016;123:2009–17.

Lyndon A, Lee HC, Gilbert WM, Gould JB, Lee KA. Maternal morbidity during childbirth hospitalization in California. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:2529–35.

Herrchen B, Gould JB, Nesbitt TS. Vital statistics linked birth/infant death and hospital discharge record linkage for epidemiological studies. Comput Biomed Res. 1997;30:290–305.

Koullali B, Kamphuis EI, Hof MH, Robertson SA, Pajkrt E, de Groot CJ, et al. The effect of interpregnancy interval on the recurrence Rate of spontaneous preterm birth: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:174–82.

Lengyel CS, Ehrlich S, Iams JD, Muglia LJ, DeFranco EA. Effect of modifiable risk factors on preterm birth: a population based-cohort. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:777–85.

Shree R, Caughey AB, Chandrasekaran S. Short interpregnancy interval increases the risk of preterm premature rupture of membranes and early delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:3014–20.

Appareddy S, Pryor J, Bailey B. Inter-pregnancy interval and adverse outcomes: evidence for an additional risk in health disparate populations. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30:2640–4.

Ahrens KA, Hutcheon JA, Ananth CV, Basso O, Briss PA, Ferre CD, et al. Report of the Office of Population Affairs’ expert work group meeting on short birth spacing and adverse pregnancy outcomes: methodological quality of existing studies and future directions for research. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2018;33:O5–14.

Hutcheon JA, Moskosky S, Ananth CV, Basso O, Briss PA, Ferre CD, et al. Good practices for the design, analysis, and interpretation of observational studies on birth spacing and perinatal health outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2018;33:O15–24.

Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:163–8.

Tucker CM, Berrien K, Menard MK, Herring AH, Daniels J, Rowley DL, et al. Predicting preterm birth among women screened by north carolina’s pregnancy medical home Program. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:2438–52.

Atreya MR, Muglia LJ, Greenberg JM, DeFranco EA. Racial differences in the influence of interpregnancy interval on fetal growth. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:562–70.

McGrady GA, Sung, John F.C., Rowley, Diane L., Hogue, Carol J.R. Preterm delivery and low birth weight among first-born infants of black and white college graduates. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:266–76.

Ekwo EE, Moawad A. The relationship of interpregnancy interval to the risk of preterm births to black and white women. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:68–73.

Carmichael SL, Kan P, Padula AM, Rehkopf DH, Oehlert JW, Mayo JA, et al. Social disadvantage and the black-white disparity in spontaneous preterm delivery among California births. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0182862.

Adams MM, Delaney KM, Stupp PW, McCarthy BJ, Rawlings JS. The relationship of interpregnancy interval to infant birthweight and length of gestation among low-risk women, Georgia. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1997;11:48–62.

Nabukera SK, Wingate MS, Owen J, Salihu HM, Swaminathan S, Alexander GR, et al. Racial disparities in perinatal outcomes and pregnancy spacing among women delaying initiation of childbearing. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:81–9.

Cofer FG, Fridman M, Lawton E, Korst LM, Nicholas L, Gregory KD. Interpregnancy Interval and Childbirth Outcomes in California, 2007-2009. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:43–51.

Zhu BP, Haines KM, Le T, McGrath-Miller K, Boulton ML. Effect of the interval between pregnancies on perinatal outcomes among white and black women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1403–10.

Class QA, Rickert ME, Oberg AS, Sujan AC, Almqvist C, Larsson H, et al. Within-family analysis of interpregnancy interval and adverse birth outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1304–11.

Wang X, Chen C, Wang L, Chen D, Guang W, French J. Conception, early pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: a population-based prospective study. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:577–84.

Practice Bulletin No. 200: early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e197–207.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the March of Dimes Prematurity Research Center at Stanford University School of Medicine and NIH R03HD090243.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lonhart, J.A., Mayo, J.A., Padula, A.M. et al. Short interpregnancy interval as a risk factor for preterm birth in non-Hispanic Black and White women in California. J Perinatol 39, 1175–1181 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-019-0402-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-019-0402-1

- Springer Nature America, Inc.

This article is cited by

-

Sexual Socialization Experiences and Perceived Effects on Sexual and Reproductive Health in Young African American Women

Sex Roles (2024)

-

Interactions between long interpregnancy interval and advanced maternal age on neonatal outcomes

World Journal of Pediatrics (2023)

-

Protective Places: the Relationship between Neighborhood Quality and Preterm Births to Black Women in Oakland, California (2007–2011)

Journal of Urban Health (2022)