Abstract

Current land surface models assume that groundwater, streamflow and plant transpiration are all sourced and mediated by the same well mixed water reservoir—the soil. However, recent work in Oregon1 and Mexico2 has shown evidence of ecohydrological separation, whereby different subsurface compartmentalized pools of water supply either plant transpiration fluxes or the combined fluxes of groundwater and streamflow. These findings have not yet been widely tested. Here we use hydrogen and oxygen isotopic data (2H/1H (δ2H) and 18O/16O (δ18O)) from 47 globally distributed sites to show that ecohydrological separation is widespread across different biomes. Precipitation, stream water and groundwater from each site plot approximately along the δ2H/δ18O slope of local precipitation inputs. But soil and plant xylem waters extracted from the 47 sites all plot below the local stream water and groundwater on the meteoric water line, suggesting that plants use soil water that does not itself contribute to groundwater recharge or streamflow. Our results further show that, at 80% of the sites, the precipitation that supplies groundwater recharge and streamflow is different from the water that supplies parts of soil water recharge and plant transpiration. The ubiquity of subsurface water compartmentalization found here, and the segregation of storm types relative to hydrological and ecological fluxes, may be used to improve numerical simulations of runoff generation, stream water transit time and evaporation–transpiration partitioning. Future land surface model parameterizations should be closely examined for how vegetation, groundwater recharge and streamflow are assumed to be coupled.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Freshwater fluxes via plant transpiration (45,000 km3 yr−1, ref. 3, to 62,000 km3 yr−1, ref. 4), streamflow (37,000 km3 yr−1 to 40,000 km3 yr−1, refs 5, 6) and groundwater recharge (12,000 km3 yr−1 to 16,200 km3 yr−1, ref. 7) are central components of the terrestrial hydrosphere. Understanding the sources of water and processes that govern each component is important for predicting the effects of global change on water security and ecosystem services6. One of the most useful tools for quantifying water-cycle components and the linkages between plant ecology and physical hydrology is stable-isotope tracing8. Global isotopic databases developed over the past 60 years9 have enabled continental-scale assessments of transpiration/evaporation ratios4 and the recycling of rainfall back into the atmosphere10.

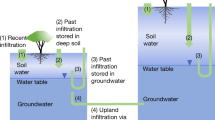

While global sets of precipitation9, streamflow9 and groundwater11 data are now available for analysis, measurements of plant xylem waters (that is, water moving within plants) remain dispersed throughout the primary, specialist literature. Synthesizing global groundwater, streamflow and plant xylem water isotopic data is important because recent watershed-based case studies have shown evidence of ecohydrological separation1,2—meaning that the soil water that supplies plant transpiration is isolated from the water that recharges groundwater and replenishes streamflow. These two recent field studies both showed that plant transpiration is supplied by waters within unsaturated soils, but that local streamflow and groundwater were supplied by mobile water (linked to infiltrating precipitation) that moves through the soil seemingly unmixed with the waters that are retained in the soil.

Compartmentalization of a poorly mobile plant transpiration water pool versus a highly mobile stream/groundwater pool, if widespread, would challenge existing land surface model parameterizations that assume that plants and streams draw from a single, well mixed subsurface water reservoir12. If true, such widespread ecohydrological separation would also have implications for isotope-based assessments of evaporation/transpiration ratios that rely on well mixed systems4. Here, we use a new global isotope database to test the ecohydrological compartmentalization hypothesis: that the isotopic composition of waters that supply plant transpiration differs from that of waters that supply groundwater and streamflow. The global ecohydrological isotope database consists of 18O/16O and 2H/1H ratios for plant xylem water (n = 1,460), soil water (n = 1,830), stream water (n = 336), groundwater (n = 2,749) and precipitation (n = 488) at 47 globally distributed locations (Table 1, Fig. 1).

The median (interquartile range) δ18O and δ2H values are: a, groundwater: −7.7 (7.4), −51.5 (62.6), n = 2,749; b, stream water: −6.2 (8.8), −37.1 (66.9), n = 336; c, plant xylem water: −5.5 (6.1), −50.6 (50.6), n = 1,460; d, soil water: −7.5 (7.4), −63.9 (52.2), n = 1,830. The inset in a shows the locations of 47 globally distributed stable isotopic data sets. The histogram borders show partitioning of the data sets at 30 identical intervals or bins. The global meteoric water line (GMWL13) is also shown. V-SMOW, Vienna-standard mean ocean water.

Our approach is predicated on the knowledge that precipitation δ2H and δ18O values (see Methods for definitions) co-vary along a regression line with a δ2H/δ18O slope of eight (this is the global meteoric water line, GMWL)13. The physical process of evaporation occurs under disequilibrium, produces a strong kinetic isotope effect that yields δ2H/δ18O slopes of less than eight14, and results in a situation in which water samples that have undergone some evaporation plot ‘below’ the regression line of precipitation isotopic data. We use this well known difference between the meteoric water line and the local evaporation line as a key marker for ecohydrological compartmentalization1,2.

Figure 1a–d shows isotopic data for groundwater, stream water, plant xylem water and soil water from our compiled database. Globally, headwater streams and groundwater plot approximately along the GMWL. These patterns suggest that stream water and groundwater follow the local precipitation input signal15. Plant xylem and soil waters extracted from the 47 studies plot below the regression of global meteoric waters—a result of the strong kinetic isotope effect via the process of evaporation14.

To quantify the similarities or differences between waters used by plants and waters that contribute to groundwater and streamflow, we use a site-by-site comparison based on a precipitation offset16:

where a and b are the slope and y intercept, respectively, calculated from monthly measurements of δ18O and δ2H from local precipitation at each study site, and S is one standard deviation measurement uncertainty for both δ18O and δ2H. The precipitation offset describes the difference in the isotopic composition of environmental waters from that of local precipitation, which has, by definition, a precipitation offset of zero. The precipitation offset can distinguish hydrological processes that occur under chemical equilibrium (for example, the condensation of vapour13) from hydrological processes that occur under disequilibrium (for example, evaporation17). Plant transpiration does not affect the precipitation offset, whereas the evaporation of meteoric water near the land surface results in precipitation offset values of less than zero. By comparing the local precipitation offsets of our four water types (that is, soil water, plant xylem water, stream water and groundwater), we can use the stable isotopes to distinguish evaporated waters from non-evaporated waters and to test whether streamflow, groundwater and plant transpiration are supplied by one well mixed subsurface water reservoir, or more than one water reservoir (namely water that is retained in the soil and water that recharges groundwater and discharges in streams).

Figure 2 shows that plant xylem water offsets (median, interquartile range, P < 0.0001 using nonparametric Steel–Dwass method) (−5.6, 4.7) and soil water offsets (−6.2, 4.4) are significantly different from the offsets of groundwater (−1.8, 3.2) and stream water (0.22, 3.7) in all five of the biomes represented by the 47 sites in our database. Of our 47 sites, 40 have groundwater precipitation offsets that are statistically distinct (P < 0.05 using two-tailed homoscedastic/heteroscedastic tests, as applicable) from both soil water and plant xylem water precipitation offsets. Our analysis is suggestive of a widespread occurrence of ecohydrological separation—that is, poor and incomplete mixing of subsurface water, with one reservoir of water sustaining plant transpiration, and another contributing to groundwater recharge and streamflow. On a site-by-site basis, groundwater and stream water have a precipitation offset that is on average respectively 5.4 and 4.8 higher (that is, closer to zero) than do soil and plant xylem waters. The greatest differences between the precipitation offsets of streamwater/groundwater and plant xylem/soil water are found in the tropical and Mediterranean biomes (7.7 and 5.4, respectively), with smaller differences observed in the arid, temperate grassland, and temperate forest biomes (3.6, 2.4 and 1.6 on average, respectively).

Extents of plant xylem (white) and soil (grey) water bars show 25th and 75th percentiles. All values of groundwater (squares) are shown for visualization of data density (that is, darker regions) and dispersion (that is, lighter regions). Mean values of stream water (circles) are also shown, as are the transpiration-amount-weighted values of plant xylem water (triangles).

Recent work has shown that different storm types contribute disproportionately to groundwater recharge (see, for example, refs 11, 18). Some studies have shown that more intense storms dominate groundwater recharge18; others present evidence to the contrary19. While our analyses do not allow us to associate storm intensity with either plant transpiration or groundwater recharge fluxes, we can nevertheless trace the isotopic composition of the precipitation from which plant xylem water originated. We calculated the intersection points of local plant xylem evaporation lines with local meteoric water lines (LMWLs)—that is, plant xylem δ source value (see Extended Data Fig. 1 and Methods):

where m, a and b are the slope of the evaporation line, the LMWL slope, and the LMWL intercept, respectively.

The results of this analysis show that at 80% of the sites (see Extended Data Table 1; 37 of 46 sites) where plant xylem water δ source values can be calculated, groundwater isotope values (median, interquartile range, P < 0.05 using nonparametric Wilcoxon method) (−52, 63‰ δ2H) are statistically different from plant xylem water δ source values (−82, 83‰ δ2H). This suggests that, in many cases (see, for example, Extended Data Fig. 2), ecologically and hydrologically important precipitation is segregated in both space and time, even before these waters become further segregated in the subsurface for plant transpiration or for groundwater recharge and streamflow (see Methods and Extended Data Figs 2 and 4).

We also use equations (2) and (3) to trace the isotopic composition of precipitation from which soil water originated—that is, the soil water δ source value. We find that at 83% of the sites (Extended Data Table 1; 29 of 35 sites) where soil water isotopic data are available, soil water δ source values (−104, 96‰ δ2H) are statistically different from groundwater isotope values. The significant difference between soil water δ source and groundwater isotope values suggests that some forms of precipitation that recharge the subsurface may be more important than others to plant transpiration fluxes. We assess the uncertainties in parameter m (equation (2)) and find overall average uncertainties of 1.07‰ for δ18O and 5.54‰ for δ2H (2σ). These are slightly less than, but somewhat comparable to, the prediction uncertainties in precipitation isotope values (1.17‰ for δ18O and 9.4‰ for δ2H; ref. 20).

Plants regulate water fluxes from the subsurface to the atmosphere4. Our discovery that ecohydrological separation is widespread throughout the terrestrial water cycle has major implications for isotope-based estimates of runoff sources12, streamwater residence times21 and evaporation/transpiration partitioning4. Recent estimates4 of catchment-scale transpiration/evapotranspiration (T/ET) ratios have followed an assumption of well mixed water stores within the critical zone, consistent with most land surface parameterizations12; our findings fundamentally challenge this assumption as it relates to catchment-based evapotranspiration partitioning4,22,23 and most land surface models12. Our work would suggest that downstream water isotope compositions are biased towards precipitation and groundwater source contributions, and do not reflect the composition of water seen in soil. This in turn casts doubt on the estimates of transpiration/evapotranspiration made in other studies if based solely on isotope data, meaning that evapotranspiration partitioning based on downstream water isotope compositions may not represent an integrated catchment-wide isotopic signature as widely applied.

Notwithstanding these issues, our general finding that transpiration comprises the greatest fraction of terrestrial evapotranspiration is reinforced by the lines of evidence discussed in ref. 4, and by the results of land surface models (terrestrial T/ET of 59% to 80%; refs 24, 25), atmospheric vapour isotope measurements (European T/ET of 62%; ref. 26), global syntheses of stand-level transpiration measurements (terrestrial T/ET of roughly 61%; ref. 3), and some but not all general circulation models (see refs 27, 28). Although transpiration is, indeed, the largest component of terrestrial evapotranspiration4, our results show that the mechanisms by which such partitioning takes place, and links to other components of the water cycle29, are still poorly understood. These combined findings point the way towards the research that is needed to understand the ecophysiological basis of ecohydrological separation across biomes. Finally, our results also suggest that existing land surface model parameterizations of plant physiological processes and runoff30 (that is, streamflow) can be made more realistic through the incorporation of ecohydrological separation.

Methods

Data compilation and treatment

We performed a keyword-based search of published literature for stable water isotopes in ecology and hydrology. Because ecohydrological separation31 is based on the offset of a water sample from the local meteoric water line (that is, ‘precipitation offset’16; equation (1)), we included only dual-isotope findings and excluded papers that used either δ2H or δ18O alone. Stable isotope values from the 47 papers found were then extracted in one of two ways: first, where data were reported in tabular form, we compiled the data directly into the database; second, where plant xylem and soil water isotope data were not reported in tabular form, we used a graphical user interface to extract data points from figures in the original paper. We then calculated the precipitation offset values on the basis of equation (1). The measurement uncertainty S in equation (1) was calculated as:

Reported analytical errors for δ2H and δ18O are 1‰ and 0.2‰ on average, respectively.

We extracted groundwater isotope data for 45 of 47 sites either from the compiled papers (n = 24) or from the comprehensive global groundwater database (n = 21) of ref. 11. Of the 21 groundwater data sets compiled using the latter database, 16, 2, 1 and 2 data sets are within a 200-, 300-, 400- and 500-km radius of actual study sites. The radii within which groundwater data were extracted were chosen so that we could build groundwater data sets for most of the 47 sites in our database. To test whether or not the choice of radii imposed a scale-dependent variation (that is, bias) in isotopic trends, we performed a sensitivity analysis by calculating the precipitation offset values of groundwater at distances of 25, 50 and 100 km. We found that precipitation offset values of groundwater did not differ statistically in space. That is, precipitation offset of groundwater at 25 km (−3.5 ± 2.2, n = 688) was not statistically different from precipitation offset at 50 km (−2.5 ± 2.4, n = 1,605), 100 km (−2.4 ± 2.4, n = 3,295), 200 km (−2.7 ± 2.2, n = 6,598), 300 km (−2.5 ± 4.5, n = 12,000), 400 km (−2.8 ± 4.6, n = 18,239) and 500 km (−2.8 ± 4.8, n = 24,000). This scale-invariant behaviour of groundwater precipitation offset supported our choice of radii in building the data sets for 45 of 47 sites in our database. It also reinforced one of the key messages of this work, in that groundwater isotopes generally fall along the local meteoric water line.

To show that plant transpiration water and groundwater recharge are related to different storm types, we traced the precipitation δ source value of plant xylem water by calculating the intersection points of local evaporation lines with local meteoric water lines (LMWLs) (equations (2) and (3); Extended Data Fig. 1). On a site-by-site basis, we compared the calculated precipitation δ source value of plant xylem water and soil water with the mean groundwater δ value (Extended Data Table 1).

Comparing plant xylem water δ source values with mean groundwater δ values requires intuitively that both should be situated as close to each other as possible at a site. The distance of groundwater wells to actual study sites in our database, however, varies from 0 km to almost 500 km. To test whether our approach of comparing both isotope composition values was statistically robust, we ran a sensitivity analysis by comparing plant xylem water δ source values with only the closest groundwater well to a given site. Increasing the radii between actual study sites and sites of groundwater measurements was then used as a critical evaluation metric for the approach (Extended Data Fig. 3). Our results showed that, for five increasing radii ranges between the actual xylem water study site and groundwater well site, the differences (median (interquartile ranges), absolute δ2H‰) between plant xylem water δ and groundwater δ values (24 (29), n = 7; 30 (30), n = 8; 31 (42), n = 7; 21 (22), n = 9; 23 (40), n = 11) are not statistically different from each other (P > 0.90, Tukey–Kramer honest significant difference). This suggests that our approach in comparing plant xylem water δ source values (that is, xylem evaporation line intercept with LMWL) and mean groundwater value at a site is valid. We underline that this does not imply that groundwater isotope values are invariant in space, but rather that the mean difference between plant xylem water δ source values and mean groundwater values is invariant in space (statistically not different), as shown in Extended Data Fig. 3.

We make a distinction between the two phenomena: ‘segregation’ of storm types and ‘ecohydrological separation’. The former is related to source precipitation analysis (equations (2) and (3)), the latter to the fate of these waters either as groundwater or for plant transpiration (equation (1)). Segregation of storm types and ecohydrological separation in space is ubiquitous in the global data set. We are unable to test for both phenomena in time because of limitations in the available information in the compiled source papers. That is, if a source paper has data for at least two time points (usually contrasting moisture time points) then we can use such information to explore temporal contrasts (38 of 47 sites). For the 38 sites that satisfy this criterion, both storm-type segregation and ecohydrological separation exist in 30 and 32 of 38 sites, respectively (P < 0.05 using nonparametric Wilcoxon Method).

We recognize that non-weighted plant xylem water isotope values would be biased towards values where transpiration rates are low. To test the robustness of the precipitation offset parameter, we also calculate the transpiration-amount-weighted isotopic composition of plant xylem water (δxyl(weighted)) using compiled long-term, global, biome-level transpiration rate estimates3:

where δxyl(i) represents the isotopic composition of xylem water during sampling month i, and  represents the amount of transpiration during month i. As illustrated in Fig. 2, both transpiration-amount-weighted and non-weighted plant xylem precipitation offsets are statistically different from zero, supporting our primary conclusion that plant transpiration water chemistries are different from groundwater and streamflow at 40 of 47 locations. We use no amount weighting on groundwater isotope values, in agreement with observations that showed little change in groundwater isotopic composition on timescales of years and decades32,33.

represents the amount of transpiration during month i. As illustrated in Fig. 2, both transpiration-amount-weighted and non-weighted plant xylem precipitation offsets are statistically different from zero, supporting our primary conclusion that plant transpiration water chemistries are different from groundwater and streamflow at 40 of 47 locations. We use no amount weighting on groundwater isotope values, in agreement with observations that showed little change in groundwater isotopic composition on timescales of years and decades32,33.

To trace the fate of water after precipitation (that is, either as groundwater recharge or as plant water uptake), we quantified the precipitation offset from the LMWL (equation (1)). We confirmed ecohydrological separation at a study site if plant xylem water and soil water isotopic composition fall below the regression of δ2H and δ18O values in local precipitation on the LMWL.

Conventional notation for isotope composition is used where δ = (Rsample/Rstandard − 1) × 1,000‰, where R is the ratio of 18O/16O (δ18O) or 2H/1H (δ2H) in the sample, or in the international standard (Vienna-standard mean ocean water, V-SMOW).

Statistical analysis

Parametric requirements of normality and equal variances, particularly for aggregate precipitation offset values, are not satisfied via attempts to transform the data. Testing whether group means are located similarly across groups is performed using nonparametric tests, which use functions of the response ranks (or rank scores). A Kruskal–Wallis/Steel–Dwass method is performed to test whether or not the precipitation offset values of the water types—groundwater, stream water, plant xylem water and soil water—differ statistically from each other. We perform a similar nonparametric test (Dunn all pairs for joint ranks method) by computing ranks on all the data. The results are the same as those from the pairwise method Kruskal–Wallis/Steel–Dwass test. To test whether each water type is statistically different from zero (that is, the precipitation offset value of local precipitation), the Dunn method for joint ranking is performed. The test shows that plant xylem water and soil water are statistically different from zero, while groundwater and stream water are not statistically different from zero. This test result supports the interpretation that groundwater and stream water fall along the δ2H/δ18O slopes of local meteoric water lines, while plant xylem water and soil water fall ‘below’ the slopes of this linear regression. The same method is also used to test for statistical significance of precipitation offset values of each water type across biomes. These nonparametric tests are based on ranks and control for the overall alpha level (α = 0.05). The Dunn method, which reports P values after a Bonferroni adjustment, is used to correct for multiple testing problem that may arise from an inflated type I error rate (0.0001 ≤ P ≤ 0.05). Where parametric requirements are met, particularly for intrasite tests on water types, Student’s t/Tukey–Kramer HSD tests are performed as applicable. Uncertainty estimation, particularly for equations (2) and (3) parameters, is performed with the jack-knifing approach34.

A mechanism for ecohydrological separation

Partial mixing of ‘new’ (incoming) and ‘old’ (resident) water in the subsurface is rarely considered in conceptual models35,36. Our key finding that groundwater/stream water and soil/plant uptake water are fundamentally (physically and temporally) separated supports the dynamic partial mixing model of ref. 37. In fact, it was the contrasting conclusions drawn by ref. 1 compared with those of refs 38 and 39 regarding the mixing mechanisms that led the authors of ref. 37 to propose the use of the following dimensionless mixing coefficient  , controlled mainly by soil moisture content:

, controlled mainly by soil moisture content:

where  and

and  are actual storage and storage capacity within the root zone, respectively;

are actual storage and storage capacity within the root zone, respectively;  and

and  are location and shape parameters, respectively; and i is the storage compartment. Equation (6) is applied to tracer (for example, stable water isotopes) balance equations, which may then enable functional comparisons amongst other alternative diagnostic models (for example, the more widely used complete mixing model).

are location and shape parameters, respectively; and i is the storage compartment. Equation (6) is applied to tracer (for example, stable water isotopes) balance equations, which may then enable functional comparisons amongst other alternative diagnostic models (for example, the more widely used complete mixing model).

Our precipitation offset parameter analysis (equation (1)) is used to modify equation (6) by substituting the precipitation offset value of soil water for the term  :

:

where  is the absolute value of precipitation offset parameter. This results in a dimensionless mixing coefficient

is the absolute value of precipitation offset parameter. This results in a dimensionless mixing coefficient  value that decreases as precipitation offset

value that decreases as precipitation offset  value increases. When

value increases. When  is applied in tracer mass balance equations (as outlined in ref. 37), mixing between ‘new’ and ‘old’ water increases as soil moisture decreases; or, conversely, separation between ‘new’, ‘fast-flowing’ waters and ‘old’, ‘matrix’ waters increases with higher antecedent soil moisture. The persistence of ‘old’ water within the soil matrix and reduced participation in dispersive and diffusive exchange with preferential flow path water lead to continued exposure to evaporation (stage 1, capillary action, and stage 2, vapour diffusion). For details regarding evaporation from porous media, see ref. 40.

is applied in tracer mass balance equations (as outlined in ref. 37), mixing between ‘new’ and ‘old’ water increases as soil moisture decreases; or, conversely, separation between ‘new’, ‘fast-flowing’ waters and ‘old’, ‘matrix’ waters increases with higher antecedent soil moisture. The persistence of ‘old’ water within the soil matrix and reduced participation in dispersive and diffusive exchange with preferential flow path water lead to continued exposure to evaporation (stage 1, capillary action, and stage 2, vapour diffusion). For details regarding evaporation from porous media, see ref. 40.

Our conceptual formulation as outlined in equation (7) is supported by the results of our precipitation offset analysis. Our analysis provides a site-by-site (Extended Data Table 2) and biome-level (Extended Data Table 3) quantification of the magnitude of separation—and, by extension, mixing—between groundwater recharge and stream discharge, and the water that recharges the soil matrix and is being taken up by plants for transpiration. Extended Data Table 3 shows that in soils of the arid biome, the precipitation offset value is highest (that is, closer to zero); conversely, in soils of the humid tropics where antecedent soil wetness is high, the precipitation offset value is lower. Calculating the dimensionless mixing coefficient  using the precipitation offset values in Extended Data Table 3 and plugging these values into equation (7) supports the observation that in the dry soils of the arid biome, mixing between new, fast-flowing waters and old, matrix waters increases. The opposite is true for the other extreme, in humid tropical soils, where antecedent soil wetness is high. In general, because plants in our compiled database use soil water, these precipitation offset trends in soils are therefore consistent with plant xylem water data. That is, the magnitude of ecohydrological separation—plants using evaporated soil water that is isotopically distinct from groundwater recharge and stream discharge—increases with antecedent soil wetness. The relationship between soil wetness and the dimensionless mixing coefficient

using the precipitation offset values in Extended Data Table 3 and plugging these values into equation (7) supports the observation that in the dry soils of the arid biome, mixing between new, fast-flowing waters and old, matrix waters increases. The opposite is true for the other extreme, in humid tropical soils, where antecedent soil wetness is high. In general, because plants in our compiled database use soil water, these precipitation offset trends in soils are therefore consistent with plant xylem water data. That is, the magnitude of ecohydrological separation—plants using evaporated soil water that is isotopically distinct from groundwater recharge and stream discharge—increases with antecedent soil wetness. The relationship between soil wetness and the dimensionless mixing coefficient  is discussed in detail and tested with actual, long-term catchment-level data in ref. 37. However, we state a caveat: the use of the precipitation offset parameter in equation (7) may be considered as a coarse (first-order) approximation given the nonlinear relationship between evaporative loss and the precipitation offset parameter.

is discussed in detail and tested with actual, long-term catchment-level data in ref. 37. However, we state a caveat: the use of the precipitation offset parameter in equation (7) may be considered as a coarse (first-order) approximation given the nonlinear relationship between evaporative loss and the precipitation offset parameter.

While ref. 1 was the first paper to develop the ecohydrological separation concept and was relatively successful at proposing a mechanistic explanation for the observed results, other work has shown that such a mechanism may not universally explain the observed ecohydrological separation. For example, ref. 2 also found ecohydrological separation in a seasonally dry cloud forest in Mexico; these authors argued that the mechanism proposed in ref. 1 was not likely to explain the observed isotopic separation in their study2. The plant xylem water values in ref. 1 are more enriched than most of the soil water values—the opposite case to ref. 2. If the ‘first in, last out’ mechanism proposed by ref. 1 was correct, then the measured plant xylem values should have matched those of (or at least be bounded by) the measured soil water values. Their data suggest that this was not the case. In contrast, the authors of ref. 2 observed their plant xylem water values to lie completely in between precipitation and bulk soil water values. The aggregate result (Extended Data Fig. 4) from our global data set lends support more to the interpretation of ref. 2 than to that of ref. 1.

Water extraction techniques

As underlined in our central message, plant xylem water and soil water isotopes plot ‘off’ the LMWLs, supporting the idea of a widespread occurrence of ecohydrological separation on a global scale. This finding is true across the different techniques used to extract water out of soil and plant stem samples in our data set. The authors of ref. 1 argued that plant transpiration is supplied by ‘tightly bound’ waters within unsaturated soils. This interpretation was inferred from the laboratory technique used to extract water out of a soil sample (cryogenic vacuum distillation), which uses suction pressures that are orders of magnitude greater than those used in other field techniques (for example, suction lysimetry). Potential nuances in the fidelity of water extraction from soil samples using existing laboratory techniques have recently been explored41,42,43. These findings suggest that soil physicochemical characteristics may contribute to isotopic fractionation, specifically with respect to δ18O. We explored the relationship between water extraction techniques and plant xylem water/soil water δ18O in our data set. Extended Data Fig. 5 shows the plant xylem water/soil water δ18O values using a liquid–vapour equilibration technique from cryogenic vacuum distillation and azeotropic distillation. Although there are statistically significant differences (P < 0.0001, nonparametric Dunn method for joint ranking) between both cryogenic vacuum (n = 2,640) and azeotropic distillation (n = 441), and liquid-vapour equilibration methods (n = 204), there is no significant difference in plant xylem water δ18O between the two more widely used techniques, cryogenic vacuum and azeotropic distillation (P = 0.35, nonparametric Dunn method for joint ranking). Despite these differences in δ18O of plant xylem water and soil water with respect to water extraction techniques, both water types plot ‘off’ the LMWL in dual-isotope space. This suggests that ecohydrological separation exists beyond any differences in soil water δ18O that are related to different water extraction techniques.

Global map of plant xylem water δ2H and δ18O

For the first time, to our knowledge, we provide not only a global map of plant xylem δ2H and δ18O, but also their relationship to respective LMWLs as integrated in the precipitation offset parameter—a fundamental descriptor of ecohydrological separation (Extended Data Fig. 6). Our compilation of global plant xylem δ2H and δ18O may complement other existing large-scale isotopic data sets from precipitation44 and streams45, in pursuing future research questions related to plant-water relations from continental to global scales.

References

Brooks, J. R., Barnard, H. R., Coulombe, R. & McDonnell, J. J. Ecohydrologic separation of water between trees and streams in a Mediterranean climate. Nature Geosci. 3, 100–104 (2010)

Goldsmith, G. R. et al. Stable isotopes reveal linkages among ecohydrological processes in a seasonally dry tropical montane cloud forest. Ecohydrol. 5, 779–790 (2012)

Schlesinger, W. H. & Jasechko, S. Transpiration in the global water cycle. Agric. For. Meteorol. 189, 115–117 (2014)

Jasechko, S. et al. Terrestrial water fluxes dominated by transpiration. Nature 496, 347–350 (2013)

Dai, A. & Trenberth, K. E. Estimates of freshwater discharge from continents: latitudinal and seasonal variations. J. Hydrometeorol. 3, 660–687 (2002)

Oki, T. & Kanae, S. Global hydrological cycles and world water resources. Science 313, 1068–1072 (2006)

Wada, Y., Van Beek, L. P. H., Wanders, N. & Bierkens, M. F. P. Human water consumption intensifies hydrological drought worldwide. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 034036 (2013)

Yakir, D. & Wang, X.-F. Fluxes of CO2 and water between terrestrial vegetation and the atmosphere estimated from isotope measurements. Nature 380, 515–517 (1996)

International Atomic Energy Agency’s Water Resources Programme http://www.iaea.org/water/ (2014)

Levin, N. E., Zipser, E. J. & Cerling, T. E. Isotopic composition of waters from Ethiopia and Kenya: Insights into moisture sources for eastern Africa. J. Geophys. Res. D 114, D23306 (2009)

Jasechko, S. et al. The pronounced seasonality of global groundwater recharge. Wat. Resour. Res. 50, 8845–8867 (2014)

Birkel, C., Tetzlaff, D., Dunn, S. M. & Soulsby, C. Towards a simple dynamic process conceptualization in rainfall-runoff models using multi-criteria calibration and tracers in temperate, upland catchments. Hydrol. Processes 24, 260–275 (2010)

Friedman, I. Deuterium content of natural waters and other substances. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 4, 89–103 (1953)

Craig, H. Isotopic variations in meteoric waters. Science 133, 1702–1703 (1961)

Dutton, A. R. Groundwater isotopic evidence for paleorecharge in U.S. High Plains aquifers. Quat. Res. 43, 221–231 (1995)

Landwehr, J. & Coplen, T. in Isotopes in Environmental Studies 132–135 (IAEA-CN-118/56, International Atomic Energy Agency, 2006)

Dansgaard, W. Stable isotopes in precipitation. Tellus 16, 436–468 (1964)

Taylor, R. G. et al. Evidence of the dependence of groundwater resources on extreme rainfall in East Africa. Nature Clim. Change 3, 374–378 (2013)

Scholl, M. A. & Murphy, S. F. Precipitation isotopes link regional climate patterns to water supply in a tropical mountain forest, eastern Puerto Rico. Wat. Resour. Res. 50, 4305–4322 (2014)

Good, S. P. et al. Patterns of local and nonlocal water resource use across the western US determined via stable isotope intercomparisons. Wat. Resour. Res. 50, 8034–8049 (2014)

Syed, T. H., Famiglietti, J. S., Zlotnicki, V. & Rodell, M. Contemporary estimates of Pan-Arctic freshwater discharge from GRACE and reanalysis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L19404 (2007)

Ferguson, P. R., Weinrauch, N., Wassenaar, L. I., Mayer, B. & Veizer, J. Isotope constraints on water, carbon, and heat fluxes from the northern Great Plains region of North America. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 21, GB2023 (2007)

Gibson, J. J. & Edwards, T. W. D. Regional water balance trends and evaporation-transpiration partitioning from a stable isotope survey of lakes in northern Canada. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 16, 10-1-10-14 (2002)

Dirmeyer, P. A. et al. GSWP-2: multimodel analysis and implications for our perceptions of the land surface. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 87, 1381–1397 (2006)

Wang-Erlandsson, L., van der Ent, R. J., Gordon, L. J. & Savenije, H. H. G. Contrasting roles of interception and transpiration in the hydrological cycle—part 1: temporal characteristics over land. Earth Syst. Dyn. 5, 441–469 (2014)

Aemisegger, F. et al. Deuterium excess as a proxy for continental moisture recycling and plant transpiration. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 4029–4054 (2014)

Sutanto, S. J. et al. A perspective on isotope versus non-isotope approaches to determine the contribution of transpiration to total evaporation. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 18, 2815–2827 (2014)

Lawrence, D. M., Thornton, P. E., Oleson, K. W. & Bonan, G. B. The partitioning of evapotranspiration into transpiration, soil evaporation, and canopy evaporation in a GCM: Impacts on land-atmosphere interaction. J. Hydrometeorol. 8, 862–880 (2007)

Gouet-Kaplan, M., Tartakovsky, A. & Berkowitz, B. Simulation of the interplay between resident and infiltrating water in partially saturated porous media. Wat. Resour. Res. 45, W05416 (2009)

Stöckli, R., Vidale, P. L., Boone, A. & Schär, C. Impact of scale and aggregation on the terrestrial water exchange: integrating land surface models and Rhône catchment observations. J. Hydrometeorol. 8, 1002–1015 (2007)

McDonnell, J. J. The two water worlds hypothesis: ecohydrological separation of water between streams and trees? WIREs Water 1, 323–329 (2014)

Darling, W. G., Bath, A. H. & Talbot, J. C. The O and H stable isotopic composition of fresh waters in the British Isles. 2. Surface waters and groundwater. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 7, 183–195 (2003)

Genty, D. et al. Rainfall and cave water isotopic relationships in two South-France sites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 131, 323–343 (2014)

Wu, C. Jackknife, bootstrap and other resampling methods in regression analysis—discussion. Ann. Stat. 14, 1261–1295 (1986)

van der Velde, Y., Torfs, P. J. J. F., van der Zee, S. E. A. T. M. & Uijlenhoet, R. Quantifying catchment-scale mixing and its effects on time-varying travel time distributions. Wat. Resour. Res. 48, W06536 (2012)

Page, T., Beven, K. J., Freer, J. & Neal, C. Modelling the chloride signal at Plynlimon, Wales, using a modified dynamic TOPMODEL incorporating conservative chemical mixing (with uncertainty). Hydrol. Processes 21, 292–307 (2007)

Hrachowitz, M., Savenije, H., Bogaard, T. A., Tetzlaff, D. & Soulsby, C. What can flux tracking teach us about water age distribution patterns and their temporal dynamics? Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 17, 533–564 (2013)

Legout, C. et al. Solute transfer in the unsaturated zone-groundwater continuum of a headwater catchment. J. Hydrol. 332, 427–441 (2007)

Klaus, J., Zehe, E., Elsner, M., Külls, C. & McDonnell, J. J. Macropore flow of old water revisited: experimental insights from a tile-drained hillslope. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 17, 103–118 (2013)

Or, D., Lehmann, P., Shahraeeni, E. & Shokri, N. Advances in soil evaporation physics—a review. Vadose Zone J. 12(4), http://dx.doi.org/10.2136/vzj2012.0163 (2013)

Oerter, E. et al. Oxygen isotope fractionation effects in soil water via interaction with cations (Mg, Ca, K, Na) adsorbed to phyllosilicate clay minerals. J. Hydrol. 515, 1–9 (2014)

Meissner, M., Koehler, M., Schwendenmann, L., Hoelscher, D. & Dyckmans, J. Soil water uptake by trees using water stable isotopes (δ2H and δ18O)–a method test regarding soil moisture, texture and carbonate. Plant Soil 376, 327–335 (2014)

Orlowski, N., Frede, H., Brüggemann, N. & Breuer, L. Validation and application of a cryogenic vacuum extraction system for soil and plant water extraction for isotope analysis. J. Sensors Sensor Syst. 2, 179–193 (2013)

Bowen, G. J. & Wilkinson, B. Spatial distribution of δ18O in meteoric precipitation. Geology 30, 315–318 (2002)

Kendall, C. & Coplen, T. B. Distribution of oxygen-18 and deuterium in river waters across the United States. Hydrol. Processes 15, 1363–1393 (2001)

Boutton, T. W., Archer, S. R. & Midwood, A. J. Stable isotopes in ecosystem science: structure, function and dynamics of a subtropical savanna. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 13, 1263–1277 (1999)

McKeon, C. et al. Growth and water and nitrate uptake patterns of grazed and ungrazed desert shrubs growing over a nitrate contamination plume. J. Arid Environ. 64, 1–21 (2006)

Snyder, K. A. & Williams, D. G. Water sources used by riparian trees varies among stream types on the San Pedro River, Arizona. Agric. For. Meteorol. 105, 227–240 (2000)

Williams, D. G. & Ehleringer, J. R. Intra- and interspecific variation for summer precipitation use in pinyon-juniper woodlands. Ecol. Monogr. 70, 517–537 (2000)

Zhou, Y.-D., Chen, S.-P., Song, W.-M., Lu, Q. & Lin, G.-H. Water-use strategies of two desert plants along a precipitation gradient in northwestern China. Chinese J. Plant Ecol. 35, 789–800 (2011)

Hai, Z., Xin-Jun, Z., Li-Song, T. & Yan, L. Differences and similarities between water sources of Tamarix ramosissima, Nitraria sibirica and Reaumuria soongorica in the southeastern Junggar Basin. Chinese J. Plant Ecol. 37, 665–673 (2013)

Lin, Z., Xing, X. & Gui-Lian, M. Water sources of shrubs grown in the northern Ningxia Plain of China characterized by shallow groundwater table. Chinese J. Plant Ecol. 36, 618–628 (2012)

Bijoor, N. S., McCarthy, H. R., Zhang, D. & Pataki, D. E. Water sources of urban trees in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Urban Ecosyst. 15, 195–214 (2012)

February, E. C., West, A. G. & Newton, R. J. The relationship between rainfall, water source and growth for an endangered tree. Austral Ecol. 32, 397–402 (2007)

Kurz-Besson, C. et al. Hydraulic lift in cork oak trees in a savannah-type Mediterranean ecosystem and its contribution to the local water balance. Plant Soil 282, 361–378 (2006)

Swaffer, B. A., Holland, K. L., Doody, T. M., Li, C. & Hutson, J. Water use strategies of two co-occurring tree species in a semi-arid karst environment. Hydrol. Processes 28, 2003–2017 (2014)

West, A. G. et al. Diverse functional responses to drought in a Mediterranean-type shrubland in South Africa. New Phytol. 195, 396–407 (2012)

Ohte, N. et al. Water utilization of natural and planted trees in the semiarid desert of Inner Mongolia, China. Ecol. Appl. 13, 337–351 (2003)

Sun, S., Huang, J., Han, X. & Lin, G. Comparisons in water relations of plants between newly formed riparian and non-riparian habitats along the bank of Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Trees Struct. Funct. 22, 717–728 (2008)

Berry, Z. C., Hughes, N. M. & Smith, W. K. Cloud immersion: an important water source for spruce and fir saplings in the southern Appalachian Mountains. Oecologia 174, 319–326 (2014)

Jia, G., Yu, X., Deng, W., Liu, Y. & Li, Y. Determination of minimum extraction times for water of plants and soils used in isotopic analysis. J. Food Agric. Environ. 10, 1035–1040 (2012)

Rong, L., Chen, X., Chen, X., Wang, S. & Du, X. Isotopic analysis of water sources of mountainous plant uptake in a karst plateau of southwest China. Hydrol. Processes 25, 3666–3675 (2011)

Tang, K. L. & Feng, X. H. The effect of soil hydrology on the oxygen and hydrogen isotopic compositions of plants' source water. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 185, 355–367 (2001)

Wang, P., Song, X., Han, D., Zhang, Y. & Liu, X. A study of root water uptake of crops indicated by hydrogen and oxygen stable isotopes: a case in Shanxi Province, China. Agric. Water Manage. 97, 475–482 (2010)

Wei, Y. F., Fang, J., Liu, S., Zhao, X. Y. & Li, S. G. Stable isotopic observation of water use sources of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica in Horqin Sandy Land, China. Trees Struct. Funct. 27, 1249–1260 (2013)

Wei, L., Lockington, D. A., Poh, S., Gasparon, M. & Lovelock, C. E. Water use patterns of estuarine vegetation in a tidal creek system. Oecologia 172, 485–494 (2013)

Zhang, W. et al. Using stable isotopes to determine the water sources in alpine ecosystems on the east Qinghai-Tibet plateau, China. Hydrol. Processes 24, 3270–3280 (2010)

Anderegg, L. D. L., Anderegg, W. R. L., Abatzoglou, J., Hausladen, A. M. & Berry, J. A. Drought characteristics’ role in widespread aspen forest mortality across Colorado, USA. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 1526–1537 (2013)

Berkelhammer, M. et al. The nocturnal water cycle in an open-canopy forest. J. Geophys. Res. D 118, 10225–10242 (2013)

Bertrand, G. et al. Determination of spatiotemporal variability of tree water uptake using stable isotopes (δ18O, δ2H) in an alluvial system supplied by a high-altitude watershed, Pfyn forest, Switzerland. Ecohydrol. 7, 319–333 (2014)

Liu, Y. et al. Analyzing relationships among water uptake patterns, rootlet biomass distribution and soil water content profile in a subalpine shrubland using water isotopes. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 47, 380–386 (2011)

Penna, D. et al. Tracing the water sources of trees and streams: isotopic analysis in a small pre-alpine catchment. Proc. Env. Sci. 19, 106–112 (2013)

Phillips, S. L. & Ehleringer, J. R. Limited uptake of summer precipitation by bigtooth maple (Acer grandidentatum Nutt) and Gambel's Oak (Quercus gambelii Nutt). Trees Struct. Funct. 9, 214–219 (1995)

Rose, K. L., Graham, R. C. & Parker, D. R. Water source utilization by Pinus jeffreyi and Arctostaphylos patula on thin soils over bedrock. Oecologia 134, 46–54 (2003)

Brunel, J. P., Walker, G. R. & Kennettsmith, A. K. Field validation of isotopic procedures for determining sources of water used by plants in a semiarid environment. J. Hydrol. 167, 351–368 (1995)

Clinton, B. D., Vose, J. M., Vroblesky, D. A. & Harvey, G. J. Determination of the relative uptake of ground vs. surface water by Populus deltoides during phytoremediation. Int. J. Phytoremed. 6, 239–252 (2004)

Eggemeyer, K. D. et al. Seasonal changes in depth of water uptake for encroaching trees Juniperus virginiana and Pinus ponderosa and two dominant C(4) grasses in a semiarid grassland. Tree Physiol. 29, 157–169 (2009)

Holland, K. L., Tyerman, S. D., Mensforth, L. J. & Walker, G. R. Tree water sources over shallow, saline groundwater in the lower River Murray, south-eastern Australia: implications for groundwater recharge mechanisms. Aust. J. Bot. 54, 193–205 (2006)

Kukowski, K. R., Schwinning, S. & Schwartz, B. F. Hydraulic responses to extreme drought conditions in three co-dominant tree species in shallow soil over bedrock. Oecologia 171, 819–830 (2013)

McCole, A. A. & Stern, L. A. Seasonal water use patterns of Juniperus ashei on the Edwards Plateau, Texas, based on stable isotopes in water. J. Hydrol. 342, 238–248 (2007)

Mensforth, L. J., Thorburn, P. J., Tyerman, S. D. & Walker, G. R. Sources of water used by riparian Eucalyptus-Camaldulensis overlying highly saline groundwater. Oecologia 100, 21–28 (1994)

Hartsough, P., Poulson, S. R., Biondi, F. & Estrada, I. G. Stable isotope characterization of the ecohydrological cycle at a tropical treeline site. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 40, 343–354 (2008)

Brunel, J. P., Walker, G. R., Dighton, J. C. & Monteny, B. Use of stable isotopes of water to determine the origin of water used by the vegetation and to partition evapotranspiration. A case study from HAPEX-Sahel. J. Hydrol. (Amst.) 188–189, 466–481 (1997)

February, E. C., Higgins, S. I., Newton, R. & West, A. G. Tree distribution on a steep environmental gradient in an arid savanna. J. Biogeogr. 34, 270–278 (2007)

Garcin, Y. et al. Hydrogen isotope ratios of lacustrine sedimentary n-alkanes as proxies of tropical African hydrology: insights from a calibration transect across Cameroon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 79, 106–126 (2012)

Deng, Y., Jiang, Z. & Qin, X. Water source partitioning among trees growing on carbonate rock in a subtropical region of Guangxi, China. Env. Earth Sci. 66, 635–640 (2012)

Evaristo, J. A., McDonnell, J. J. & Scholl, M. A. Evidence for ecohydrological separation across contrasting sites in a wet tropical low seasonality catchment. Hydrol. Processes (submitted)

Nie, Y. et al. Seasonal water use patterns of woody species growing on the continuous dolostone outcrops and nearby thin soils in subtropical China. Plant Soil 341, 399–412 (2011)

Rosado, B. H. P., De Mattos, E. A. & Sternberg, L. D. S. L. Are leaf physiological traits related to leaf water isotopic enrichment in restinga woody species? An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 85, 1035–1045 (2013)

Schwendenmann, L., Pendall, E., Sanchex-Bragado, R., Kunert, N. & Holsher, D. Tree water uptake in a tropical plantation varying in tree diversity: interspecific differences, seasonal shifts and complementarity. Ecohydrol. 8, 1–12 (2014)

Acknowledgements

J.E. thanks the Saskatchewan Innovation and Opportunity Scholarship, Global Institute for Water Security, and School of Environment and Sustainability (University of Saskatchewan) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J.M. conceived the idea of testing the ecohydrological compartmentalization hypothesis with global data. J.E., S.J. and J.J.M. brainstormed on how to do this. J.E. designed the approach, compiled the data set, and conducted the statistical analyses. J.E. wrote the first paper draft. S.J. and J.J.M. edited and commented on the manuscript and contributed to the text in later iterations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Figure 1 Schematic representation of tracing the isotopic composition of source precipitation.

Plant xylem water isotopic values plot on a linear regression called the evaporation line. The point on the local meteoric water line (LMWL) where the plant xylem water evaporation line intersects provide a good approximation of the mean isotopic value of plant xylem source precipitation. The same method is used in tracing the soil water δ source value.

Extended Data Figure 2 Tracing the isotopic composition of plant xylem source precipitation versus mean groundwater value.

Plant xylem water (grey triangles, n = 88) plotted in δ18O–δ2H space. Shown are the mean plant xylem source precipitation value (green triangle with error bars, ±1 s.d., n = 88), mean groundwater value (blue circle with error bars, ±1 s.d., n = 271), amount-weighted average precipitation (yellow star), GMWL (solid black line) and LMWL (dashed black line). This is an example of a case in Oregon, USA (ref. 1) where mean groundwater isotope value is more positive than plant xylem source precipitation value. This is the case in 41 of 47 sites in our database.

Extended Data Figure 3 The difference between plant xylem δ-source precipitation values and mean groundwater δ2H values, plotted against increasing distance of groundwater locations from actual plant xylem study sites.

The extents of the boxes show the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers show the extents of outliers. Also shown are median (interquartile range) values (P > 0.90, Tukey–Kramer honest significant difference) for five (n = 7; n = 8; n = 7; n = 9; n = 11) arbitrary distance ranges.

Extended Data Figure 4 Groundwater and plant xylem source precipitation.

Plot of δ18O versus δ2H for global plant xylem water (green triangles, n = 1,460), soil water (grey circles, n = 1,830), and groundwater (blue circles, n = 2,749). Also shown are the isotopic composition of source precipitation that leads to groundwater recharge (blue circle with error bars, mean ± 1 s.d.) and precipitation that leads to plant water uptake (green triangle with error bars, mean ± 1 s.d.). The inset shows the linear regression of plant xylem water and soil water, forming distinct evaporation lines (ELs) whereby, at a site level, plant xylem water is completely bounded by soil water. Also shown are GMWL and LMWL in the main plot and inset, respectively.

Extended Data Figure 5 Comparison of plant xylem (black boxes) and soil water (grey boxes) δ18O, based on water extraction techniques.

Cryogenic vacuum (n = 2,640) and azeotropic distillation (n = 441) are significantly different from liquid–vapour equilibration methods (n = 204) (P < 0.0001, nonparametric Dunn method for joint ranking). Cryogenic vacuum and azeotropic distillation are not significantly different from each other (P = 0.35, nonparametric Dunn method for joint ranking). The extents of the boxes show the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers show the extents of outliers. Also shown are median (interquartile range) values for each water type and water extraction technique.

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Evaristo, J., Jasechko, S. & McDonnell, J. Global separation of plant transpiration from groundwater and streamflow. Nature 525, 91–94 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14983

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14983

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Elastic deformation as a tool to investigate watershed storage connectivity

Communications Earth & Environment (2024)

-

Soil pore water evaporation and temperature influences on clay mineral paleothermometry

Communications Earth & Environment (2024)

-

Determining the source water and active root depth of woody plants using a deuterium tracer at a Savannah site in northern Stampriet Basin, Namibia

Hydrogeology Journal (2024)

-

Shift in groundwater recharge of the Bengal Basin from rainfall to surface water

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Hydrological characteristics and water quality change in mountain river valley on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau

Applied Water Science (2023)