Abstract

Background:

Subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) undergoes major changes in obesity, but little is known about the whole-genome scale patterns of these changes or about their variation between different obesity sub-groups. We sought to compare how transcriptomics profiles in SAT differ between monozygotic (MZ) co-twins who are discordant for body mass index (BMI), whether the profiles vary between twin pairs and whether the variation can be linked to clinical characteristics.

Methods:

We analysed the transcriptomics (Affymetrix U133 Plus 2.0) patterns of SAT in young MZ twin pairs (n=26, intra-pair difference in BMI >3 kg m−2, aged 23–36), from 10 birth cohorts of adult Finnish twins. The clinical data included measurements of body composition, insulin resistance, lipids and adipokines.

Results:

We found 2108 genes differentially expressed (false discovery rate (FDR)<0.05) in SAT of the BMI-discordant pairs. Pathway analyses of these genes revealed a significant downregulation of mitochondrial oxidative pathways (P<0.05) and upregulation of inflammation pathways (P<0.05). Hierarchical clustering of heavy/lean twin ratios, representing effects of acquired obesity in the transcriptomics data, revealed three sub-groups with different molecular profiles (FDR<0.05). Analyses comparing these sub-groups showed that, in the heavy co-twins, downregulation of the mitochondrial pathways, especially that of branched chain amino acid degradation was more evident in two clusters while and upregulation of the inflammatory response was most evident in the last, presumably the unhealthiest cluster. High-fasting insulin levels and large adipocyte diameter were the predominant clinical characteristic of the heavy co-twins in this cluster (Bonferroni-adjusted P<0.05).

Conclusions:

This is the first study in BMI-discordant MZ twin pairs reporting sub-types of obesity based on both SAT gene expression profiles and clinical traits. We conclude that a decrease in mitochondrial BCAA degradation and an increase in inflammation in SAT co-occur and associate with hyperinsulinemia and large adipocyte size in unhealthy obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) has an important metabolic function in storing and mobilising energy. During obesity development, SAT, containing adipocytes and stromal-vascular cells that include fibroblastic connective tissue cells as well as preadipocytes, macrophages and leucocytes,1, 2 undergoes major expansion and remodelling.3, 4, 5, 6 Changes include an increase in number and size of adipocytes, infiltration of adipose tissue (AT) by immune cells and relative rarefaction of blood vessels and neural structures.3, 4, 5, 6

Whole-genome scale SAT transcriptomics studies have revealed various genes and pathways associated with upregulation of inflammation7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and immune response,7, 8 and downregulation of mitochondrial pathways,8, 10, 12 insulin-signalling13 and lipid metabolism8 in obesity. Further, targeted SAT transcriptomics studies comparing metabolically (MHO) healthy and unhealthy (MUO) obese individuals have found more downregulation of branched chain amino acid (BCAA) degradation in MUO than in MHO group.14 In a similar study, weight gain increased lipid metabolism and synthesis in MHO but not in MUO individuals.15 These studies suggest that although obesity affects AT gene expression in general, the responses may vary depending on the obese person’s metabolic health status.

Although there have been a few studies on SAT gene expression comparing obese and lean groups or groups with different clinical health parameters, little is known about whether a hypothesis-free transcriptomics analysis can identify distinct SAT gene expression profiles in obesity, which link to metabolic health. In ordinary studies comparing obese and lean individuals, part of the gene expression differences can be driven by differences in genetic background. To this end, we employ a study design of young adult MZ twin pairs highly discordant for body mass index (BMI). This study design allows us to analyse effects of acquired obesity independent of genetic background. We first examined whole-genome scale SAT gene expression differences between all BMI-discordant MZ co-twins, that is, an effect of overweight in general. We then clustered the twin pairs to determine whether the effects of acquired obesity show different molecular and clinical profiles manifesting as heterogeneity of obesity in general population. Lastly, we verified the results in an already published material of BMI-discordant MZ twins.10

Materials and methods

Subjects

The discovery phase of the study included 26 BMI-discordant (within-pair difference, ΔBMI ⩾3 kg m−2) MZ twin pairs (males n=9, females n=17) recruited from two longitudinal population-based studies of Finnish twins, FinnTwin16 (born between 1975–1979, n=2839 pairs) and FinnTwin12 (born between 1983–1987, n=2578 pairs).16 The participants have been described previously as has the targeted analysis of genes regulating the mitochondria.11, 12 In brief, the mean BMI difference within the twin pairs was 6 kg m−2, and mean age 30.2 years at the time of clinical study. The twins were healthy, with the exception of one obese twin with inactive ulcerative colitis (treated with mesalazine and azathioprine), and another obese twin with T2DM (treated with metformin and insulin). The replication set comprised 13 healthy BMI-discordant MZ twin pairs (males n=8, females n=5, mean BMI difference within-twin pairs=5.25 kg m−2, mean age=25.6) from an already published data set,10 obtained from (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/). Four twin pairs exist in the discovery and replication data set but discovery data set samples were taken 6 years after the replication data set. We obtained written informed consent from all participants and designed the study protocol in accordance to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration with approval from the Ethics Committee of the Helsinki University Central Hospital.

Clinical measures were obtained as described previously (Table 1).12, 17 We used dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA)18 to measure body composition, magnetic resonance imaging to determine body fat distribution of abdominal subcutaneous and intra-abdominal fat, and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) to determine liver fat.19 We measured fasting lipids, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), leptin, adiponectin, as well as glucose and insulin during a 2-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). The plasma BCAA (valine, leucine and isoleucine) values were measured using a high-throughput NMR metabolomics platform.17 We also recorded nutritional intake with a 3-day food diary, physical activity by Baecke indices.12, 20 Current daily smoking status for the twins was assessed by questionnaire.

AT morphology

We obtained SAT biopsies via a surgical technique under local anaesthesia. We photographed the SAT adipocytes with a light microscope and measured the diameters of 200 cells using ImageJ.21, 22

Transcriptomics analyses

We used the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Redwood City, CA, USA) to extract SAT RNA,12 treated it with DNase I (Qiagen) and hybridised 250 ng to Affymetrix U133Plus2.0 microarray (Affymetrix, www.affymetrix.com) to detect gene expression.11 We normalised the expression data using R-Bioconductor23 package GCRMA,24 and performed annotation with Brainarray cdf version 18.25

First, we analysed whether within-pair differences for heavy/lean status differed between males and females (by comparing the beta coefficients using linear models for microarray analysis [limma]).26

Second, we used limma to identify differentially expressed genes within the co-twins. P-values were corrected for multiple testing (Benjamini and Hochberg method).27 We considered false discovery rate (FDR)<0.05 as statistically significant. In this paired design model, as the twin pairs were perfectly matched for sex, sex did not provide any additional information to the model. We further examined the differential gene expression on pathway level using ingenuity pathway analysis tool (IPA, Qiagen).

Cluster analyses

Third, we explored whether the twin pairs cluster based on within-pair gene expression ratios (heavy/lean). We used weighted gene co-expression network analysis (R-WGCNA)28 to perform hierarchical clustering. We then performed moderated two-sided t-tests (limma), using sex as a covariate, on the gene expression data to obtain differentially expressed genes within the pairs in each cluster. In this paired design model, although the twin pairs were matched for sex, sex distribution between the clusters differed and was adjusted for. Next, we tested whether the original top ten differentially expressed pathways within the 26 twin pairs were cluster-specific using IPA’s comparison analysis. Lastly, we determined each cluster’s pathways individually using the IPA’s canonical pathway analysis. Fisher’s exact test P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Replication data set

Clinical measures of the replication data set are as described previously10 (Supplementary Table 1). However, we lacked data for insulin area under the curve (AUC) and glucose AUC during OGTT, adiponectin and BCAA, nutritional intake and physical activity that were measured in the discovery data set. Within-twin pair differences in gene expression for this data set have already been published,10 and in this study, we used the data set to verify the cluster analysis results.

Basic statistics (discovery and replication data sets)

We used Wilcoxon’s signed rank tests in R software29 to measure means of the clinical measurements in the heavy and lean groups. In addition, we used one-way Anova with Tukey’s posthoc tests in R software29 to calculate mean differences within pairs in each cluster. FDR⩽0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Twin pairs were highly discordant for clinical characteristics of obesity

As reported previously,12 the lean and heavy co-twins were highly discordant (P<0.0001) for all measures of adiposity (Table 1). In addition, the heavy co-twins were more insulin-resistant (higher fasting insulin and insulin AUC during OGTT), had higher levels of low-density lipoprotein, triacylglycerol, serum hs-CRP and leptin, and lower levels of high-density lipoprotein and adiponectin. The lean twins had significantly higher Baecke sports indices. Most twins were non-smokers, but three pairs were concordant and six pairs discordant for smoking status. The replication set10 was similar to the current data set for all clinical measures (Supplementary Table 1). Four pairs were concordant and three pairs discordant for smoking status. Other pairs were not smokers.

2108 genes were differentially expressed in SAT within the BMI-discordant pairs

Altogether 2108 genes were differentially expressed (FDR<0.05) between the lean and heavy co-twins in SAT, 945 (45%) of which were upregulated in the heavy co-twins. Between males and females, these genes had a correlation value of 0.899 (P-value<0.0001) (Supplementary Figure 1). Although this correlation was high, we decided to altogether minimise the possible effects of sex by adjusting subsequent cluster models for sex. Among the 2108 genes differentially expressed, the top 10 up- and downregulated genes are shown in Table 2 (full list in Supplementary Table 2). The most upregulated gene in the heavy co-twins was EGFL6 (fold change 8.90), which has a role in the regulation of cell cycle, proliferation, and developmental processes. Genes involved in apoptosis and immune response were amongst the top 10 upregulated genes.

The most downregulated gene in the heavy co-twins, SLC27A2 (fold change 0.1848) is associated with lipid biosynthesis and fatty acid degradation. The remaining top nine downregulated genes are involved in lipid and fatty acid metabolism, and cell signalling processes.

Top ten pathways mostly associated with mitochondrial function, lipid metabolism and inflammation

We then analysed the 2108 differentially expressed genes with IPA's pathway analysis to obtain their biological pathways. The ten most significant differentially expressed pathways are presented in Figure 1. Five of these are shown in detail in Supplementary Figures 2–6.

Top 10 biological pathways for the differentially expressed genes within 26 BMI-discordant monozygotic twin pairs. The numbers above the bars represent the genes belonging to the respective pathways (IPA). The left y axis represents the percentage of overlap between the study data set and the known genes belonging to the respective pathways. The y axis on the right displays the −log of P-value, calculated by Fisher's right-tailed exact test showing increased significance. A −log(P-value) of 1.3 is indicative of P-value of 0.05. The bars show the percentage of upregulated (dark grey) and downregulated (light grey) genes in the heavy co-twins in the study data set. The white blocks represent the genes belonging to the pathway but which did not reach significance.

The top pathway was oxidative phosphorylation. Out of all the genes in this pathway, those that were also in our differentially expressed genes were downregulated in the heavy co-twins (Supplementary Figure 2). The mitochondrial dysfunction pathway included the same significantly downregulated genes as the oxidative phosphorylation pathway and in addition, upregulated genes GSR and CYB5R3, which are involved in mitochondrial oxidative stress reactions (Supplementary Figure 3). Majority of the genes in the BCAA pathways, valine degradation I (Supplementary Figure 4) and isoleucine degradation I also encode genes that function in the mitochondria and were downregulated in the heavy co-twins. The genes in the glutaryl-CoA degradation pathway (Supplementary Figure 5), all downregulated in the heavy co-twins, participate in tryptophan and lysine degradation and many of them are shared with the isoleucine degradation pathway.

In addition to the pathways discussed above, the differentially expressed pathways included triacylglycerol biosynthesis (Supplementary Figure 6), the transcripts of which were mostly downregulated in the heavy co-twins. Also ketogenesis and ketolysis pathways were differentially expressed in SAT between the co-twins. These two pathways share two genes (HADHA, HADHB), which are also involved in the fatty acid β-oxidation pathway30 and two genes (ACAT1, ACAT2) also involved in isoleucine degradation (IPA). Nur77 Signalling in T-lymphocytes and unfolded protein response pathways had both up- and downregulated genes in our heavy co-twins. These two pathways have a role in inflammation and ER stress, respectively, suggesting an effect in these processes in obesity, although our data was unable to conclusively show upregulation or downregulation.

Gene expression profiling can be used in identifying obesity sub-types

Next, we explored whether the SAT transcriptomics profiles can characterise different forms of acquired obesity. Cluster analysis using gene expression ratios between heavy and lean co-twins revealed three clusters (Figure 2). The first cluster (Cluster 1) had two, the second cluster (Cluster 2) 19 and the third cluster (Cluster 3) five twin pairs. Because of unequal sex distribution in the clusters (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5), sex was included as a covariate in the cluster analysis. Cluster 1 had 413, Cluster 2 had 728 and Cluster 3 had 828 differentially expressed genes within the twin pairs (Supplementary Table 3) (FDR<0.05). Most of the genes were specific for each cluster with four shared genes between Cluster 1 and 3 and 110 shared genes between Cluster 2 and 3 (Supplementary Figure 7). The clusters’ clinical characteristics are presented in Supplementary Table 4.

Cluster tree for the twin pair ratios of gene expression data (n=14 665 genes). Cluster 1 had a total of 274 differently expressed genes (139 upregulated, 135 downregulated), Cluster 2 had 728 differently expressed genes (290 upregulated, 438 downregulated) and Cluster 3 had 828 differently expressed genes (503 upregulated, 325 downregulated) within the twin pairs. Twin pair ratios (n=26 BMI-discordant pairs) for the gene expression were used for the cluster analysis.

We then performed IPA pathway analyses for the within-twin pair differentially expressed genes for each cluster separately. For some pathways, IPA was able to (via z-scores) conclusively show upregulation/downregulation. Among the pathways that differed between the co-twins in Cluster 1 (Figure 3a), none reached significant z-scores. In Cluster 2 (Figure 3b), most of the top 10 pathways were involved in mitochondrial functions (two pathways were downregulated and one upregulated in the heavy co-twins). In Cluster 3, the significant pathways (Figure 3c) were strongly upregulated in the heavy co-twins and involved in immune response.

The top 10 pathways of the clusters based on the within-twin pair differences in gene expression. Differentially expressed genes for each cluster (FDR<0.05, n=274 for Cluster 1, n=728 for Cluster 2, n=828 for Cluster 3) were entered into IPA to produce the pathways. (a) Cluster 1, (b) Cluster 2 and (c) Cluster 3. The y axis displays the −log of P-value which is calculated by Fisher's exact right-tailed test. A-log(P-value) of 1.3 is indicative of P-value of 0.05. The percentage of upregulated (dark grey) and downregulated (light grey) genes in the heavy co-twins in the data set is represented. The white blocks represent the genes that belong to the pathway according to IPA analysis but did not reach significance. For some pathways, IPA was able to conclusively provide activation scores: (z-scores which show statistical significance of the observed number of ‘activated’ and ‘inhibited’ genes; <0: inhibited, >0: activated). z-scores >2 or <−2 are considered significant. For Cluster 2, IPA predicted the following pathways to be downregulated (EIF2 signalling (z=−2.309) and the following pathways to be upregulated: mTOR signalling (z=0.378) and IL-8 signalling (z=1.414). For Cluster 3, IPA predicted the following pathways in Cluster 3 to be upregulated: CD28 signalling in T-helper cells: (z=2.688), TREM1 signalling (z=4.123), B-cell receptor signalling (z=3.128), role of pattern recognition receptors in recognition of bacteria and viruses (z=4.00), role of NFAT in regulation of the immune response (z=3.578), iCOS-iCOSL signalling in T-helper cells (z=2.309).

Then, we checked how the original top 10 pathways (Figure 1) obtained in the analysis on all 26 twin pairs behaved in each cluster. IPA's comparison analysis revealed that compared to Cluster 1, the other two clusters’ pathways had more affected genes (Supplementary Figure 8). In Cluster 3, Nur77 signalling in T-lymphocytes (inflammation) and valine degradation were more prominent than in Cluster 1 or 2. Compared to Cluster 1 and 3, Cluster 2 had more affected genes in the mitochondrial pathways.

Replication data set reveals similar patterns as the study data set for cluster 3

To validate the robustness of these clusters, we repeated the cluster analysis on previously published data on BMI-discordant MZ twin pairs. Owing to a very small replicate data set, we considered nominal P-values <0.05 as significant. The differentially expressed genes on the replication data set revealed three clusters (Supplementary Figures 9 and 10) which we then analysed for the pathways (Supplementary Figure 11).

The pathways in Cluster 1 (Supplementary Figure 11a) and Cluster 2 (Supplementary Figure 11b) were not clearly similar to Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 of the study data set. However, like in the study data set, the replication data set showed upregulation of immune and inflammatory response for Cluster 3 (Supplementary Figure 11c). The results from the replication data set (Supplementary Figure 12) showed a general consistent pattern across the three clusters whereby, as we move from Cluster 1 to 2 towards Cluster 3, the representation of genes responsible for immune/inflammatory response increase.

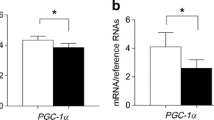

Inflammatory response and BCAA degradation significantly different in cluster 3 in both data sets

We then selected a few pathways of interest to closely compare the clusters in both data sets. We selected two mitochondrial pathways (oxidative phosphorylation and BCAA degradation) and two inflammatory pathways (humoral immune response and inflammatory response) because of their top appearance either in the study or replication data set. We found that for both data sets (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 12) Cluster 2 and 3 showed higher enrichment for BCAA degradation and Cluster 3 for inflammatory response in the heavy co-twins compared to Cluster 1.

Pathways of Clusters 1–3 compared for selected functions. Differentially expressed genes for each cluster (FDR<0.05, n=274 for Cluster 1, n=728 for Cluster 2, n=828 for Cluster 3) were entered into IPA to compare the selected pathways. The y axis displays the −log of P-value which is calculated by Fisher's exact right-tailed test. A-log(P-value) of 1.3 is indicative of a P-value of 0.05.

Cluster 3 was associated with high-fasting insulin levels and adipocyte diameter

We then performed multiple group comparison analysis to ascertain clinical measurements differences in the three clusters. The results of the discovery data set (Supplementary Table 4) showed that differences between the heavy and leaner co-twins were larger for Cluster 3 than in Cluster 2 for fasting insulin levels (Bonferroni-adjusted P=0.041) and adipocyte diameter (adjusted P=0.045). The replication data set also showed that within-pair differences of fasting insulin were larger in Clusters 3 (adjusted P=0.02) and 2 (adjusted P=0.005) than in Cluster 1 (Supplementary Table 5). The within-pair differences in other obesity-associated clinical parameters did not differ between the three clusters.

Discussion

This study reveals two fundamental changes in the SAT transcriptomics profiles of heavy versus lean co-twins of BMI-discordant MZ twin pairs: a downregulation of mitochondrial and upregulation of inflammatory pathways. The most pronounced differences between the co-twins were observed for oxidative phosphorylation and BCAA (especially valine and isoleucine) degradation pathways, suggesting an effect on mitochondrial function in obesity. Also, an effect on inflammation in the heavy co-twins was observed, although not nearly as prominent as the mitochondrial finding.

In addition, our extended hierarchical clustering analyses of gene expression of heavy/lean twin ratios revealed that the transcriptomics profiles defined three patterns of acquired obesity. Our results suggest that in Cluster 1, the transcriptional differences between the heavy and leaner co-twins were more benign, but that in Cluster 2 and 3, the intensification of mitochondrial downregulation was seen, and finally, in Cluster 3, a clear inflammatory pattern in the heavy co-twins. Many of these results, especially those of Cluster 3, were verified in a previously published replication data set of BMI-discordant MZ twin pairs.10 Both the study and the replication data sets showed increased fasting insulin levels in the heavy twins of Cluster 3 than in the other clusters, perhaps suggesting that the defined AT transcriptomics profiles associate with development of the insulin-resistant phenotype in acquired obesity. In the discovery data set, the intra-pair difference in adipocyte size was also larger in Cluster 3.

In the first part (analysis of 26 twin pairs) of the study, we identified 2108 differentially expressed genes between the heavy and lean co-twins. These genes mapped to several mitochondria- and inflammation-related pathways. For the mitochondria-related pathways, genes from our data set were mostly downregulated in the heavy co-twins. For inflammation-related pathways, some genes from our data set were downregulated and some upregulated, in the heavy co-twins. Similar results were observed in the replication data set: mitochondrial oxidative pathways, especially BCAA catabolism, were downregulated together with upregulation of a number of inflammatory pathways in the heavy co-twins.10 Mitochondrial downregulation (mitochondrial DNA copy number, mRNA and protein expression) in obese SAT was also observed in a series of targeted analyses performed for the same twins as in the current study.21 A couple of other studies also suggest lower expression of genes encoding mitochondrial proteins in SAT in overweight subjects.8, 31 Studies also show that mitochondrial respiration in human fat cells is significantly reduced with increasing BMI.32, 33

Although the triggering events for the mitochondrial downregulation in obese fat are not known, it can be assumed that in energy overload, ATP production by cytosolic processes such as glycolysis are activated and mitochondria are needed less. Insufficiency of mitochondrial catabolism was noted for both fatty acids and BCAAs. It should also be noted that although ketogenesis and ketolysis appear as two significant pathways, these processes occur in the liver and thus showed up in our data set probably because of the shared genes with fatty acid oxidation and BCAA catabolism.

Altogether with overall oxidative phosphorylation, the most significantly enriched pathway in our heavy co-twins was BCAA degradation. The cluster analyses revealed that downregulation of mitochondrial and BCAA degradation-related pathways worsened towards the higher clusters 2 and 3, suggesting that these processes are related to a metabolically more disadvantaged obesity. We consider these as the most novel results of our study. BCAAs (valine, leucine and isoleucine) are essential amino acids catabolised by BCAT1 in the cytosol and thereafter by a number of genes in the mitochondria. We specifically show a significant downregulation of the mitochondrial genes, and interestingly, a twofold upregulation of the cytosolic BCAT1 (Supplementary Table 3). Similar findings have been reported in other studies.31 Blood BCAA levels have been reported as increased,34, 35, 36 and BCAA breakdown product alpha-ketoisocaproate as decreased along with decreased AT BCAA catabolism activity in obesity.10 Unfortunately, our measured levels of valine, leucine and isoleucine did not show any significant differences between the Clusters, which could be because of lower statistical power owing to missing data for some of our twins. However, studies by other researchers suggest that the decrease in AT BCAA catabolism does contribute significantly to circulating BCAA levels37, 38 and that the gene expression of the BCAA catabolism enzymes in obesity is downregulated in AT, but not in liver nor muscle.39 Increased BCAA levels have not only been correlated with insulin resistance36, 40, 41, 42 but also predict future risk of T2DM.34, 41 Here we show that, in what we assume as the more advanced stage of metabolic dysfunction in SAT, the decrease in BCAA catabolism pathways is more pronounced and associated with higher fasting insulin levels in the heavy co-twins. Previously, we showed that reduced BCAA catabolism in obesity correlates with a paradoxical reduction of adipogenesis pathways in SAT, and perhaps thereof, with accumulation of liver fat.10 Interestingly, quite recently, isotope studies in adipocytes demonstrated that BCAA catabolism improves adipocyte differentiation.43 With decreased BCAA catabolism in obesity, SAT may fail to enlarge adequately,43 which in turn may favour deposition of ectopic fat and subsequent effects on insulin sensitivity.44 Thus, our study provides a mechanistic link (reduction in mitochondrial catabolism of BCAAs) for the association between circulating BCAA and the risk of T2DM.

For reasons that are incompletely understood, downregulation of mitochondrial pathways and upregulation of inflammatory pathways in SAT often coexist.10, 11 In the present study, we noted the co-occurrence of these phenomena, but only in the higher clusters. Because mitochondrial ‘dysfunction’ only appeared in Clusters 2 and 3, and inflammation only in Cluster 3, these clusters possibly represent the metabolically more disadvantaged obesity. The order of causation remains unknown: it is possible that the mitochondria fail first as a reaction to overload of incoming energy (Cluster 2 and 3), and because the adipocytes are no longer viable, in a later stage (Cluster 3), inflammatory cells clear the dying adipocytes. Alternatively, inflammation in AT may hamper mitochondrial function.45, 46, 47, 48

The inflammatory pathways enriched in Cluster 3 of the study data set were mainly involved in B and T-helper cell activation, indicating that infiltration of these cell types in the SAT is increased in the heavy co-twins of Cluster 3 but not in the other clusters. Why the inflammatory response seen in the present study is mainly of lymphocyte origin remains an open question. It is possible that factors produced and secreted by adipocytes and/or macrophages enter the circulation and activate lymphocytes.49 Alternatively, lymphocytes may precede macrophage infiltration in obese AT presenting an early inflammatory stage that may itself modify the number and the activation state of AT macrophages.50, 51, 52, 53 It is also possible that the true inflammatory response of AT involves a complex mixture of cell types and cellular events, as has been seen in other recent obesity studies.54 Activation of the inflammasome pathway in Cluster 3 heavy co-twins in our study also points to a general inflammatory activation.

To see these molecular differences from a clinical perspective, we then analysed the clinical differences between twin pairs. The results (Supplementary Table 4) showed that Cluster 3 differed from Cluster 2 and 1 for fasting insulin levels and adipocyte size, suggesting that the heavy co-twins in Cluster 3 had a more marked insulin resistance along with larger adipocytes compared to their co-twins than the heavy co-twins in the other two clusters. The coexistence of mitochondrial pathway downregulation, large adipocyte size, inflammatory pathway upregulation in SAT and higher circulating levels of insulin in the heavy twins in Cluster 3 suggests that these phenomena may be biologically connected. Interestingly, large adipocytes have also previously been suspected to be linked to mitochondrial downregulation21 and inflammation in AT,55 and mitochondrial dysfunction and low-grade inflammation co-occur in insulin-resistant subjects’ AT.56 However, the mechanisms underpinning these connections require further studies.

The MZ co-twin study represents perhaps the best controlled study design available in humans because of the complete or close match for genes, age, gender, and intrauterine and childhood environment. As the genetic background is identical in each pair, acquired factors must account for the BMI discordance. With only six twin pairs discordant for smoking (both leaner and heavier co-twins being smokers), we cannot draw any conclusions about the effects of smoking on obesity. Alternatively, having leaner co-twins with higher Baecke sports index, hints at the possible positive effects of exercise. Food diaries, subject to significant underreporting especially by overweight people, did not reveal any differences between the co-twins.57

While comparing such matched groups of lean and heavy individuals has multiple advantages, there are also limitations. Despite extensive screening of nationwide cohorts, we only identified 26 BMI-discordant young adult twin pairs. Also, the independent contributions of the different SAT cells (stromavascular cells and adipocytes) to the results cannot be determined. In addition, measuring the transcripts levels does not necessarily translate to levels of functional proteins. This cross-sectional study also doesn’t allow us to determine cause and effect. The twins may begin to exhibit different molecular and clinical symptoms with age or varying stages of obesity. The relatively low number of subjects per cluster also provided lower statistical power. Because Cluster 1 had only two twin pairs, no definitive conclusions may be drawn regarding this cluster. Also in the replication data set, the number of twin pairs is low. The clusters themselves may represent different genetic populations, a hypothesis worth studying in the future in larger data sets.

In conclusion, there are elements of mitochondrial downregulation and activation of inflammation and immune response in the SAT transcriptomics profiles in acquired obesity, and these changes may be specifically related to a certain subgroup or sub-groups of obese persons. Our results highlight that not all obesities are the same. Accordingly, identifying obesity sub-types and profiling them using clinical traits and gene expression may facilitate improved diagnostics and personalised obesity treatment.

References

Fruhbeck G . Overview of adipose tissue and its role in obesity and metabolic disorders. Methods Mol Biol 2008; 456: 1–22.

Trayhurn P . Adipocyte biology. Obes Rev 2007; 8: 41–44.

Cinti S, Mitchell G, Barbatelli G, Murano I, Ceresi E, Faloia E et al. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res 2005; 46: 2347–2355.

Cancello R, Henegar C, Viguerie N, Taleb S, Poitou C, Rouault C et al. Reduction of macrophage infiltration and chemoattractant gene expression changes in white adipose tissue of morbidly obese subjects after surgery-induced weight loss. Diabetes 2005; 54: 2277–2286.

Cinti S . The adipose organ. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2005; 73: 9–15.

Cinti S . The adipose organ: morphological perspectives of adipose tissues. Proc Nutr Soc 2001; 60: 319–328.

Nair S, Lee YH, Rousseau E, Cam M, Tataranni PA, Baier LJ et al. Increased expression of inflammation-related genes in cultured preadipocytes/stromal vascular cells from obese compared with non-obese Pima Indians. Diabetologia 2005; 48: 1784–1788.

van Erk M,J, Pasman WJ, Wortelboer HM, van Ommen B, Hendriks HFJ . Short-term fatty acid intervention elicits differential gene expression responses in adipose tissue from lean and overweight men. Genes Nutr 2008; 3: 127–137.

Lee YH, Nair S, Rousseau E, Allison DB, Page GP, Tataranni PA et al. Microarray profiling of isolated abdominal subcutaneous adipocytes from obese vs non-obese Pima Indians: increased expression of inflammation-related genes. Diabetologia 2005; 48: 1776–1783.

Pietilainen KH, Naukkarinen J, Rissanen A, Saharinen J, Ellonen P, Keranen H et al. Global transcript profiles of fat in monozygotic twins discordant for BMI: pathways behind acquired obesity. PLoS Med 2008; 5: e51.

Naukkarinen J, Heinonen S, Hakkarainen A, Lundbom J, Vuolteenaho K, Saarinen L et al. Characterising metabolically healthy obesity in weight-discordant monozygotic twins. Diabetologia 2014; 57: 167–176.

Heinonen S, Buzkova J, Muniandy M, Kaksonen R, Ollikainen M, Ismail K et al. Impaired mitochondrial biogenesis in adipose tissue in acquired obesity. Diabetes 2015;.64: 3135–3145.

Walley AJ, Jacobson P, Falchi M, Bottolo L, Andersson JC, Petretto E et al. Differential coexpression analysis of obesity-associated networks in human subcutaneous adipose tissue. Int J Obes 2012; 36: 137–147.

Badoud F, Lam KP, DiBattista A, Perreault M, Zulyniak MA, Cattrysse B et al. Serum and adipose tissue amino acid homeostasis in the metabolically healthy obese. J Proteome Res 2014; 13: 3455–3466.

Fabbrini E, Yoshino J, Yoshino M, Magkos F, Tiemann Luecking C, Samovski D et al. Metabolically normal obese people are protected from adverse effects following weight gain. J Clin Invest 2015; 125: 787–795.

Kaprio J . Twin studies in Finland 2006. Twin Res Hum Genet 2006; 9: 772–777.

Soininen P, Kangas AJ, Wurtz P, Tukiainen T, Tynkkynen T, Laatikainen R et al. High-throughput serum NMR metabonomics for cost-effective holistic studies on systemic metabolism. Analyst 2009; 134: 1781–1785.

Pietrobelli A, Formica C, Wang Z, Heymsfield SB . Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry body composition model: review of physical concepts. Am J Physiol 1996; 271: E941–E951.

Graner M, Seppala-Lindroos A, Rissanen A, Hakkarainen A, Lundbom N, Kaprio J et al. Epicardial fat, cardiac dimensions, and low-grade inflammation in young adult monozygotic twins discordant for obesity. Am J Cardiol 2012; 109: 1295–1302.

Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE . A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr 1982; 36: 936–942.

Heinonen S, Saarinen L, Naukkarinen J, Rodriguez A, Fruhbeck G, Hakkarainen A et al. Adipocyte morphology and implications for metabolic derangements in acquired obesity. Int J Obes 2014; 38: 1423–1431.

Rao JNK, Scott AJ . On chi-squared tests for multiway contingency tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data, 1984; 12: 46–60.

Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol 2004; 5: R80.

Wu Z, Irizarry RA, Gentleman R, Martinez-Murillo F, Spencer F . A model-based background adjustment for oligonucleotide expression arrays. J Am Stat Assoc 2004; 99: 909–917.

Dai M, Wang P, Boyd AD, Kostov G, Athey B, Jones EG et al. Evolving gene/transcript definitions significantly alter the interpretation of GeneChip data. Nucleic Acids Res 2005; 33: e175–e175.

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43: e47.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y . Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 1995; 57: 289–300.

Langfelder P, Horvath S . Fast R functions for robust correlations and hierarchical clustering. J Stat Softw 2012; 46.

R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. The R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2008.

Houten SM, Wanders RJA . A general introduction to the biochemistry of mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation. J Inherit Metab Dis 2010; 33: 469–477.

Mardinoglu A, Heiker JT, Gartner D, Bjornson E, Schon MR, Flehmig G et al. Extensive weight loss reveals distinct gene expression changes in human subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 14841.

Yin X, Lanza IR, Swain JM, Sarr MG, Nair KS, Jensen MD . Adipocyte mitochondrial function is reduced in human obesity independent of fat cell size. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99: E209–E216.

Fischer B, Schottl T, Schempp C, Fromme T, Hauner H, Klingenspor M et al. Inverse relationship between body mass index and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacity in human subcutaneous adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2015; 309: E380–E387.

McCormack SE, Shaham O, McCarthy MA, Deik AA, Wang TJ, Gerszten RE et al. Circulating branched-chain amino acid concentrations are associated with obesity and future insulin resistance in children and adolescents. Pediatr Obes 2013; 8: 52–61.

Newgard CB, An J, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Stevens RD, Lien LF et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab 2009; 9: 311–326.

She P, Van Horn C, Reid T, Hutson SM, Cooney RN, Lynch CJ . Obesity-related elevations in plasma leucine are associated with alterations in enzymes involved in branched-chain amino acid metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2007; 293: E1552–E1563.

Lynch CJ, Adams SH . Branched-chain amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014; 10: 723–736.

Herman MA, She P, Peroni OD, Lynch CJ, Kahn BB . Adipose tissue branched chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism modulates circulating BCAA levels. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 11348–11356.

Mardinoglu A, Kampf C, Asplund A, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, Edlund K et al. Defining the human adipose tissue proteome to reveal metabolic alterations in obesity. J Proteome Res 2014; 13: 5106–5119.

Shah SH, Crosslin DR, Haynes CS, Nelson S, Turer CB, Stevens RD et al. Branched-chain amino acid levels are associated with improvement in insulin resistance with weight loss. Diabetologia 2012; 55: 321–330.

Wang TJ, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Cheng S, Rhee EP, McCabe E et al. Metabolite profiles and the risk of developing diabetes. Nat Med 2011; 17: 448–453.

Adams SH . Emerging perspectives on essential amino acid metabolism in obesity and the insulin-resistant state. Adv Nutr 2011; 2: 445–456.

Green CR, Wallace M, Divakaruni AS, Phillips SA, Murphy AN, Ciaraldi TP et al. Branched-chain amino acid catabolism fuels adipocyte differentiation and lipogenesis. Nat Chem Biol 2015; 12: 15–21.

Dubois SG, Heilbronn LK, Smith SR, Albu JB, Kelley DE, Ravussin E et al. Decreased expression of adipogenic genes in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Obesity 2006; 14: 1543–1552.

Valerio A, Cardile A, Cozzi V, Bracale R, Tedesco L, Pisconti A et al. TNF-alpha downregulates eNOS expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in fat and muscle of obese rodents. J Clin Invest 2006; 116: 2791–2798.

Dahlman I, Forsgren M, Sjogren A, Nordstrom EA, Kaaman M, Naslund E et al. Downregulation of electron transport chain genes in visceral adipose tissue in type 2 diabetes independent of obesity and possibly involving tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Diabetes 2006; 55: 1792–1799.

Guilherme A, Virbasius JV, Puri V, Czech MP . Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008; 9: 367–377.

Pietilainen KH, Rog T, Seppanen-Laakso T, Virtue S, Gopalacharyulu P, Tang J et al. Association of lipidome remodeling in the adipocyte membrane with acquired obesity in humans. PLoS Biol 2011; 9: e1000623.

Travers RL, Motta AC, Betts JA, Bouloumie A, Thompson D . The impact of adiposity on adipose tissue-resident lymphocyte activation in humans. Int J Obes 2015; 39: 762–769.

Deiuliis J, Shah Z, Shah N, Needleman B, Mikami D, Narula V et al. Visceral adipose inflammation in obesity is associated with critical alterations in tregulatory cell numbers. PLoS ONE 2011; 6: e16376.

Nishimura S, Manabe I, Nagasaki M, Eto K, Yamashita H, Ohsugi M et al. CD8+ effector T cells contribute to macrophage recruitment and adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Nat Med 2009; 15: 914–920.

Feuerer M, Herrero L, Cipolletta D, Naaz A, Wong J, Nayer A et al. Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nat Med 2009; 15: 930–939.

Winer S, Chan Y, Paltser G, Truong D, Tsui H, Bahrami J et al. Normalization of obesity-associated insulin resistance through immunotherapy. Nat Med 2009; 15: 921–929.

Mraz M, Haluzik M . The role of adipose tissue immune cells in obesity and low-grade inflammation. J Endocrinol 2014; 222: R113–R127.

Xiao L, Yang X, Lin Y, Li S, Jiang J, Qian S et al. Large adipocytes function as antigen-presenting cells to activate CD4(+) T cells via upregulating MHCII in obesity. Int J Obes 2016; 40: 112–120.

Soronen J, Laurila PP, Naukkarinen J, Surakka I, Ripatti S, Jauhiainen M et al. Adipose tissue gene expression analysis reveals changes in inflammatory, mitochondrial respiratory and lipid metabolic pathways in obese insulin-resistant subjects. BMC Med Genomics 2012; 5: 9.

Pietilainen KH, Korkeila M, Bogl LH, Westerterp KR, Yki-Jarvinen H, Kaprio J et al. Inaccuracies in food and physical activity diaries of obese subjects: complementary evidence from doubly labeled water and co-twin assessments. Int J Obes 2010; 34: 437–445.

Acknowledgements

We thank the twins for their invaluable contribution to the study. The Obesity Research Unit team and the staff at the Finnish Twin Cohort Study are acknowledged for their help in the collection of the data. This study was supported by The Academy of Finland (Grant numbers 266286 to KHP, 251316 to MO, and 141054, 265240, 263278 and 264146 to JK); Centre of Excellence in Research on Mitochondria, Metabolism and Disease (FinMIT) to KHP (Grant 272376), Center of Excellence in Complex Disease Genetics (Grants 213506 and 129680 to JK); Helsinki University Central Hospital (NL, AH, AR, KHP); The University of Helsinki Research Funds (MO, KHP); grants from following Foundations: Novo Nordisk (KHP), Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas (KHP), The Sigrid Juselius Foundation (MO), Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation (KHP) and Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research (KHP). Data collection in FinnTwin16 and FinnTwin12 was supported by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grants AA-12502 and AA-09203 to RJ Rose).

Author contributions

KHP designed the research, supervised the work, and participated in discussion and revision of the results. MM analysed all the data and wrote the full draft of the manuscript. KHP, SH, JK and AR collected the study data; and KHP, HYJ, JK and AR collected the replication data. AH, JL and NL participated in the imaging of the twins. JK was responsible for the base cohorts from which the discordant pairs were sampled. MO participated in discussions related to analysis and interpretation of the findings, helped in drafting the manuscript and critically commented on it. SH, HYJ, AH, JL, NL, JK, AR and KHP reviewed the manuscript draft. KHP is the guarantor of this work and as such had full access to the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muniandy, M., Heinonen, S., Yki-Järvinen, H. et al. Gene expression profile of subcutaneous adipose tissue in BMI-discordant monozygotic twin pairs unravels molecular and clinical changes associated with sub-types of obesity. Int J Obes 41, 1176–1184 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2017.95

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2017.95

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Altered H3K4me3 profile at the TFAM promoter causes mitochondrial alterations in preadipocytes from first-degree relatives of type 2 diabetics

Clinical Epigenetics (2023)

-

White adipose tissue mitochondrial bioenergetics in metabolic diseases

Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (2023)

-

Gene co-expression networks are associated with obesity-related traits in kidney transplant recipients

BMC Medical Genomics (2020)

-

New Mechanisms of Vascular Dysfunction in Cardiometabolic Patients: Focus on Epigenetics

High Blood Pressure & Cardiovascular Prevention (2020)

-

Plasma metabolites reveal distinct profiles associating with different metabolic risk factors in monozygotic twin pairs

International Journal of Obesity (2019)