Abstract

Background/Objective:

In Chile, approximately one in three children under 6 years of age reported overweight/obese, while one in four children in elementary school suffer from obesity. There is a paucity of population-based information on the influence of childhood eating behavior on anthropometric measures related to obesity. To assess the association between eating behavior scores and Body Mass Index (BMI) z-scores in 7–10-year-old Chilean children.

Subjects/Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study in 1058 children aged 7–10 (51% girls) from the ‘Growth and Obesity Chilean Cohort Study’ (GOCS). Direct measures of weight and height were used to compute BMI z-scores according to World Health Organization (WHO) curves. Children were classified as normal weight (−1<1 s.d.), overweight (1<2 s.d.) and obese (⩾2 s.d.). Eating behavior scores were measured through the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ), previously adapted and validated for Chilean children. Multiple linear regressions were carried out using BMI z-score as the outcome and eating behavior scores as explanatory variables. All models were adjusted by age and gender.

Results:

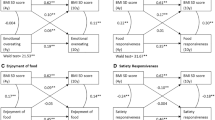

BMI z-scores were positively associated with pro-intake scores in the subscales ‘enjoyment of food’, ‘emotional overeating’ and ‘food responsiveness’ (P<0.0001). Contrary to other studies, ‘desire for drinks’ scores were also associated with BMI z-scores (P<0.0001). In contrast, food-avoidant ‘satiety responsiveness’, ‘slowness in eating’ and ‘food-fussiness’ scores were negatively associated with BMI z-scores (P<0.0001).

Conclusion:

We found a significant relationship between eating behavior scores and BMI z-scores in Chilean children, showing that BMI in 7–10-year-old Chilean children is positively associated with pro-intake eating behavior scores and negatively associated with anti-intake eating behavior scores. The identification of specific eating behaviors patterns related to obesity will provide important information for the implementation of prevention programs for this disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is the result of overeating behaviors coupled with sedentary habits. In Chile, 33% of children under 6 years of age in primary health care reported overweight/obese,1 while it is estimated that approximately one in four elementary school children suffer from obesity.2, 3 In this context, it is not only important to know the amount of food consumed, but also eating habits.4, 5 It is believed that eating behavior is under biological and social control,6, 7 with temporal stability from childhood to adulthood.8 It has been shown that obese children display lower response to internal signs of satiety,9, 10, 11 eat faster in the course of a meal12, 13, 14 and are more sensitive to advertising of non-healthy food,15 compared with normal-weight children. On the other hand, eating behavior scores are strongly and gradually associated with obesity.16, 17

The Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ)18, 19 is a psychometric tool that covers eight eating behavior dimensions (subscales) measured with high levels of internal consistency.16, 20, 21 We have previously evaluated the factorial validity and internal consistency of CEBQ in Chilean children, finding positive associations between specific eating behavior scores and obesity.22

In the present study, we wish to confirm the magnitude of associations using independent data from a large sample size of children belonging to the ‘Growth and Obesity Chilean Cohort Study (GOCS)’. Thus, the objective of this study was to assess the association between eating behavior scores and body mass index (BMI) z-scores in 7–10-year-old Chilean children.

Study design, subjects and methods

Study design

The Growth and Obesity Cohort Study (GOCS)23 was initiated in 2006 in collaboration with the Chilean National Preschool Program (JUNJI) as well as the Chilean National School Board Program (JUNAEB) and financed by FONDECYT 1100206. All children aged 2.6–4.0 years attending public nursery schools in six neighborhoods in Santiago were invited to participate in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: (i) single births with birthweight between 2500 and 4500 g and (ii) absence of physical and psychological conditions that could alter growth. The mothers of 1195 children (from 1498 eligible participants, ~80%) were included in the study. No significant differences were found in terms of age, gender and birth anthropometry of those enrolled and not enrolled. Public nursery schools in Chile serve low- to middle-income children providing free early education and food 5 days per week (from 8 AM to 5 PM) during 11 months of the year. GOCS participants did not significantly differ from the population of children attending public nursery schools in 2006 in terms of gender (53% girls), socioeconomic status (15% vulnerability) and anthropometry at birth (weight=3420 g, height=49.9 cm, BMI=13.7 kg/m2). In this study, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis of children with available data on anthropometry, eating behavior scores and physical fitness measured in 1058 children who were 7–10 years of age (50.8% girls), evaluated during 2010 and 2011. The sample size provides adequate power (>80%; with a confidence >90%) to detect significant differences in eating behavior scores based in previous studies.22 Written informed consents were obtained from parents or guardians together with the assent of the child in a protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Nutrition and Food Technology (INTA), University of Chile.

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric measurements (weight, height) were carried out using standardized techniques by trained personnel, as described elsewhere.24, 25, 26 BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). We estimated BMI for age (BMI z-scores) based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 growth reference,27 with normal weight defined as between −1 and 1 s.d.; overweight as >1 and 2 s.d.; and obese as >2 s.d.

Child eating behavior questionnaire (CEBQ)

Eating behavior was assessed with the CEBQ, as described elsewhere. The Chilean version of this questionnaire is available under request from the authors.18, 22 The questionnaire consists of 35 items measuring eight subscales of eating behavior. The items are statements about child behavior answered by the mother or guardian on a Likert scale (1: never; 5: always) (Table 1). Four subscales refer to positive inclinations for eating (Pro-intake): Enjoyment of food (EF), Food Responsiveness (FR), Emotional Overeating (EOE) and Desire to Drink (DD); while the other four subscales evaluated negative inclinations of food intake (Anti-intake): Satiety Responsiveness (SR), Slowness in Eating (SE), Emotional Undereating (EUE) and Food Fussiness (FF). For each participant, the score for each subscale was calculated as the sum of individual scores for each subscale, divided by the total number of items (Figure 1). When only two items were missing, a mean-imputation method was applied. The sum of the pro-intake scores (four subscales) and the sum of anti-intake scores (four subscales) were calculated as a measure of child eating behavior. Pro-intake/anti-intake scores were represented as a radar chart in which the top part shows the four pro-intake subscales while the bottom part shows the four anti-intake subscales. Finally, an individual summary measure of eating behavior, the ratio between these two sums (Ratio Pro-intake/Anti-intake or RPA) was calculated.

Statistical analysis

Results are shown as median±interquartile range or average±s.d., as appropriate. Analysis of variance and Kruskall–Wallis tests were used to compare summary statistics of continuous variables by gender and nutritional status groups.

Multiple linear regression analysis was carried out to assess the association between eating behavior scores and BMI z-scores, and was adjusted by age and gender. Initially, nine bivariate models were considered using BMI-z as the outcome and each eating behavior subscale. A significant result was considered when P<0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out with the STATA 9.

Results

Table 2 shows summary statistics of the 1058 participants in this study. The prevalence of obesity in the whole group was 23.9% and BMI-z was significantly higher in boys compared with girls (1.80±0.84 versus 1.69±0.77 respectively; P=0.013). As we expected, most anthropometric variables differed by obesity status after adjusting for age and sex. In our study, pro-intake eating behavior scores were strongly associated with gender, after adjusting for age and BMI-z (P-value<0.001 for all pro-intake subscales), with higher scores of these subscales in boys compared with girls. In addition, higher scores of SE were found in girls compared with boys (P<0.001) while lower scores of EUE were estimated in girls than in boys (P=0.02). No significant differences by gender were found for SR and FF. Figure 2 shows a graded and direct association between pro-intake scores (EOE, EF, FR, DD) and obesity status (P⩽0.001).

Childhood eating behavior scores according CEBQ. Scores expressed as medians. The ‘ratio’ was calculated as the ratio between the sum of scores of the pro-intake subscales divided of the sum of scores of anti-intake subscales. DD, Desire to drink; EF, Enjoyment of food; EOE, Emotional overeating; EUE, Emotional undereating; FR, Food responsiveness; FF, Food fussiness; SR, Satiety responsiveness; SE, Slowness in eating.

A negative association was observed between the anti-intake eating behavior scores and obesity (P⩽0.001), with lower scores in obese children compared with normal-weight of overweight children, with the exception of EUE scores. The pro-intake/anti-intake ratios differed significantly by gender, with slightly higher scores in girls (median: 0.96; interquartile range: 0.72–1.29) than in boys (median: 1.12; interquartile range: 0.82–1.55). No differences in eating behavior scores were observed by gender in the subset of obese children. Table 3 shows the association between BMI score and eating behavior scores, adjusting for age and gender.

Discussion

Our study shows that obese and overweight children in our sample have higher scores on pro-intake subscales of eating behavior and lower scores on anti-intake subscales compared with normal-weight children, independent of gender and age.29, 30, 31 At the same time, important differences in eating behavior scores were found by gender. For this reason, results are presented separately for boys and girls. Different hypotheses have been proposed to explain why children with higher BMI show higher scores in pro-intake subscales. Higher scores of FR and EF may be explained by increased response among obese children to external food signals like advertising, which is related to unhealthy food choices and/or increased episodes of ‘eating without hunger’.20, 29 Reyes et al.32 found that an important proportion of Chilean adolescents showed unhealthy satiety responsiveness and, in fact, they did eat when exposed to a permissive environment. The higher scores in EOE and DD in obese children might be explained by differential reaction against stress.17 The lower score in SR in obese children may reflect their lack of capacity to regulate their food consumption once the meal is initiated, as it has been demonstrated in observational studies of obese and normal-weight adults.33 Lower scores of FF and SE in obese children may indicate that, as BMI-z increases, children are less restrictive in food choices and eat faster than lean children.34, 35 Similar to the findings of Sleddens et al.35 and Santos et al.22 in our study, EUE did not achieve statistical significance in relation to BMI-z, which may indicate that these scores are not relevant in the determination of body weight. In our study, DD was significantly associated with BMI-z in contrast to the findings of Sleddens et al.35 and Santos et al.22 This may reflect the large sample size of our study and the relation of DD scores with consumption of sugar-sweetened soft drinks.36 In normal-weight children, we found that girls showed a greater tendency towards anti-intake behavior relative to boys, which represents a common pattern of eating behavior found adolescent girls compared to boys in girls compared with boys. Further research is required to define the role of gender in eating behavior during childhood. In general, the results of our research are similar to the case–control study published by Santos et al.22 in Chilean children. We have replicated most of these associations using a larger sample size in the context of a population-based cohort study in Chilean children. In addition, we report how eating behavior profiles differ by nutritional status, thus contributing to obese/overweight subjects have greater susceptibility to gain weight faster than normal-weight children. It is important to analyze the magnitude of the pro-intake/anti-intake ratio, as it serves to signal a balanceserves to signal a balance between pro-intake inclinations related to how much children may eat versus satiety signals. Using this pro-intake/anti-intake ratio as an indicator of pro-obesity behavior might provide important information in support of obesity preventive programs a useful tool for evaluating children in clinical practice and/or at the population level.

Our study has some strengths and several limitations. For strengths, it is worth noting that the large sample size (>1000 children) provides sufficient statistical power to detect significant associations between eating behavior scores and obesity, given our preliminary research work on CEBQ validation.28 In any case, there are unavoidable limitations derived from the cross-sectional nature of this study (rather than longitudinal) and the subjective information derived from eating questionnaires.

In conclusion, we have found a significant and gradual relationship between eating behavior scores and BMI z-scores in Chilean children, showing that BMI in 7–10-year-old Chilean children is positively associated with pro-intake eating behavior scores and negatively associated with anti-intake eating behavior scores. The identification of specific eating behaviors patterns related to obesity.

References

Deis, Ministerio de Salud 2010, Gobierno de Chile. Available from http://intradeis.minsal.cl/reportesrem/2010/PBC_NINOS_NUTRICION_cas_2/PBC_NINOS_NUTRICION_cas_2.aspx.

Atalah E . Epidemiología de la Obesidad en Chile. Rev Med Clinc Condes 2012; 23: 117–123.

Mazza C, Kovalskys I . Epidemiology of childhood obesity in Latinamerican countries. Med Infant 2002; 9: 299–304.

Osorio J, Weisstaub G, Castillo C . Desarrollo de la conducta alimentaria en la infancia y sus alteraciones. Rev Chil Nutr 2002; 29: 280–285.

Obregón A, Pettinelli P, Santos JL . Childhood obesity and eating behaviour. J Pediatr Endocr Met 2014; 28: 497–502.

Santos JL . Sistema leptina - melanocortinas en la regulación de la ingesta y el peso corporal. Rev Med Chile 2009; 137: 1225–1234.

Palma J, Iriarte J . Appetite regulation: neuroendocrine basis and clinical approaches. Med Clin (Barc) 2012; 139: 70–75.

Fraley RC, Roberts BW . Patterns of continuity: a dynamic model for conceptualizing the stability of individual differences in psychological constructs across the life course. Psychol Rev 2005; 112: 60–74.

Fisher JO, Cai GW, Jaramillo SJ, Cole SA, Comuzzie AG, Butte NF . Heritability of hyperphagic eating behavior and appetite related hormones among Hispanic children. Obesity 2007; 15: 1484–1495.

Fisher JO, Birch LL . Eating in the absence of hunger and overweight in girls from 5 to 7 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr 2002; 76: 226–231.

Moens E, Braet C . Predictors of disinhibited eating in children with and without overweight. Behav Res Ther 2007; 45: 1357–1368.

Barkeling B, Ekman S, Rossner S . Eating behavior in obese and normal weight 11-year-old children. Int J Obes 1992; 16: 355–360.

Drabman RS, Cordua GD, Hammer D, Jarvie GJ, Horton W . Developmental-trends in eating rates of normal and overweight preschool-children. Child Dev 1979; 50: 211–216.

Agras WS, Kraemer HC, Berkowitz RI, Korner AF, Hammer LD . Does a vigorous feeding style influence early development of adiposity. J Pediatr 1987; 110: 799–804.

Jansen A, Theunissen N, Slechten K, Nederkoorn C, Boon B, Mulkens S et al. Overweight children overeat after exposure to food cues. Eat Behav 2003; 4: 197–209.

Senra C, Seoane G, Vilas V, Sánchez-Cao E . Comparison of 10- to 12-year-old boys and girls using a Spanish version of the children’s eating attitudes test. Personality and Individual Differences 2007; 42: 947–957.

Webber L, Hill C, Saxton J, Van Jaarsveld CH, Wardle J . Eating behaviour and weight in children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33: 21–35.

González A, Santos JL . Adaptación y aplicación del cuestionario de conducta de conducta de alimentación infantil CEBQ. In: Martínez A, Portillo M (eds), Fundamentos de Nutrición y Dietética Parte II: Bases Metodológicas y Aplicaciones. España: Editorial Medica Panamericana, Madrid, Spain 2011, pp 339–344.

Stassen Berger K . La adolescencia: el desarrollo biosocial. In: Stassen Berger K (ed). Psicología del Desarrollo: Infancia y Adolescencia. Editorial Panamericana: Madrid, España, 2007, pp 435–442.

Viana V, Sinde S, Saxton J . Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire: associations with BMI in Portuguese children. Brit J Nutr 2008; 100: 445–450.

Lozano Jiménez C . Anorexia simple en la infancia, etiopatogenia y actitud terapéutica. In: Hernández Rodríguez M (ed), Alimentación Infantil. Editorial Díaz de Santos: Madrid, España, 2001, pp 193–196.

Santos J, Ho-Urriola J, Gonzalez A, Smalley SV, Dominguez-Vasquez P, Cataldo R et al. Association between eating behavior scores and obesity in Chilean children. Nutr J 2011; 10: 108–116.

Corvalan C, Uauy R, Stein AD, Kain J, Martorell R . Effect of growth on cardiometabolic status at 4 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 90: 547–555.

Unidad de Nutrición MINSAL, Consejo Asesor de Nutrición, Grupo de Expertos. Norma técnica de evaluación nutricional del niño de 6 a 18 años. Reporte Técnico Rev Chil Nutr 2004; 31: 128–137.

Van der Kooy K, Seidell JC . Techniques for the measurement of visceral fat: a practical guide. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998; 17: 187–196.

Corvalan C, Uauy R, Mericq V . Obesity is positively associated with dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate concentrations at 7 y in Chilean children of normal birth weight. Am J Clin Nutr 2013; 97: 318–325.

De Onis M, Onyango A, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J . Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85: 660–667.

Carnell S, Wardle J . Measuring behavioural susceptibility to obesity: validation of the child eating behaviour questionnaire. Appetite 2007; 48: 104–113.

Wardle J, Guthrie CA, Sanderson S, Rapoport L . Development of the Children's Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. J Child Psychol Psyc 2001; 42: 963–970.

Carnell S, Wardle J . Appetite and adiposity in children: evidence for a behavioral susceptibility theory of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 88: 22–29.

Delgado-aros S, Cremonini F, Castillo JE, Chial HJ, Burton DD, Ferber I et al. Independent influences of body mass and gastric volumes on satiation in humans. Gastroenterology 2004; 126: 432–440.

Reyes M, Hoyos V, Martinez SM, Lozoff B, Castillo M, Burrows R, Blanco E, Gahagan S . Satiety responsiveness and eating behavior among Chilean adolescents and the role of breastfeeding. Int J Obes 2014; 38: 552–557.

Carruth BR, Skinner J, Houck K, Moran J, Coletta F, Ott D . The phenomenon of ‘picky eater’: a behavioural marker in eating patterns of toddlers. J Am Coll Nutr 1998; 17: 180–186.

Cerro N, Zeunert S, Simmer KN, Daniels LA . Eating behaviour of children 1,5–3,5 years born preterm: parents’ perceptions. J Paediatr Child Health 2002; 38: 72–78.

Sleddens E, Kremers S, Thijs C . The Children's Eating Behaviour Questionnaire: factorial validity and association with body mass index in Dutch children aged 6–7. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008; 5: 49–58.

Sweetman C, Wardle J, Cooke L . Soft drinks and 'desire to drink' in preschoolers. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008; 5: 60.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by FONDECYT 1100206, 1120326 and 1150416.

Author contributions

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—US, GW and JS designed the research and wrote the manuscript; US analyzed the data and had primary responsibility for the final content. CC and RU were final reviewers for scientific content and language. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez, U., Weisstaub, G., Santos, J. et al. GOCS cohort: children's eating behavior scores and BMI. Eur J Clin Nutr 70, 925–928 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2016.18

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2016.18

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Omega-3 polygenic score protects against altered eating behavior in intrauterine growth-restricted children

Pediatric Research (2023)

-

Association between the dietary literacy of children's daily diet providers and school-age children's nutritional status and eating behaviours: a cross-sectional study

BMC Public Health (2022)

-

Interactions between a polygenic risk score for plasma docosahexaenoic fatty acid concentration, eating behaviour, and body composition in children

International Journal of Obesity (2022)

-

Breastfeeding and maternal eating behaviours are associated with child eating behaviours: findings from the ROLO Kids Study

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2021)

-

Eating behavior trajectories in the first 10 years of life and their relationship with BMI

International Journal of Obesity (2020)