Abstract

Purpose

Eating-out and prevalence of obesity/overweight have been rising rapidly in China in the past two decades due to social economic developments. This study examined Chinese school children’s eating-out behaviors and associated factors, including their association with obesity during a 3-year follow.

Methods

Data were collected from 3313 primary and middle school children aged 7–16 years in five mega-cites across China in 2015, 2016 and 2017, in an open cohort study. Eating-out behaviors were assessed using questionnaire survey. The Chinese age-sex-specific body mass index (BMI) cutoffs were used defining child overweight/obesity (combined) and obesity; central obesity was defined as WHtR ≥ 0.48. Mixed effect models examined associations between child eating-out behaviors and BMI, overweight and obesity in this longitudinal data, adjusting for other covariates.

Results

About 80.1% of the children reported having eaten out ≥ 1 times/week over the past 3 months; 46.7% and 70.9% chose Western- and Chinese-style food when ate out, respectively. Meanwhile, 29.8% of them were overweight/obese, 12.7% were obese and 20.1% had central obesity. Child eating-out behaviors were positively associated with parents’ eating-out behaviors (p < 0.05). Boys were more likely to choose Western-style food than girls (OR 1.27; 95% CI 1.09–1.48) when eating out. Compared to non-overweight/obese children, those being overweight/obese at baseline were less likely to eat out dining on Western-style food during the follow-up.

Conclusion

Eating-out is common among school children in major cities in China, but with considerable differences across groups. Children’s weight status was associated with eating-out behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

People’s lifestyles and the disease burden have been changing rapidly in China in the past two decades due to social economic developments [1,2,3]. National data show that from 1985 to 2014, the combined prevalence of overweight and obesity among school children in China increased from 2.6 to 19.5% [4, 5]. Childhood obesity has many health consequences, including increasing the risk of acquiring non-communicable chronic diseases such as diabetes, coronary heart disease and some cancers later in life [6].

Dietary intake is one of the several lifestyle factors that can be adjusted to help promote a healthy body weight [7]. One important aspect of dietary intake is eating behavior. Previous research predominately conducted in western societies, especially in the USA, shows that eating away from home is associated with poor diet quality and larger portions compared with eating home-prepared foods [8,9,10,11]. The number of restaurants and fast food restaurants providing opportunities to eat out has grown rapidly in China in the past 20 years [12]. For example, the National Bureau of Statistics reports that the average consumption of catering services among urban residents in China increased nearly 2.5 times between 2007 and 2008 [13]. A growing number of families choose to eat out or order food from restaurants rather than cooking meals at home. This phenomenon is expedited by the booming of online network food delivery in China. It is reported that the frequency of eating out affects the risk of childhood obesity [14]. Such changes of eating behaviors in China may have contributed to the growing obesity epidemic in China [15, 16]. In particular, eating-out behaviors and overweight and childhood obesity prevalence have been rising [17, 18]. Eating-out behavior, especially unhealthy eating habits, play critical roles in the development of childhood obesity, and need to be targeted in fighting the epidemic [19,20,21,22,23]. Therefore, it is of great interest to study children’s eating-out behaviors and its relationship with overweight/obesity.

The present study aimed to fill these gaps and examined: (1) children’s eating-out behaviors in five major cities across China; (2) the associations between eating out (including the frequency and type of foods) and childhood obesity, to examine how one might affect the other, using longitudinal data collected across 3 years; and (3) the other factors associated with eating-out behaviors (e.g., pocket money, parental eating behaviors etc.). We hypothesized that there might be a bidirectional relationship between eating out and childhood obesity: those who ate out more frequently or those who consumed more unhealthy restaurant foods (i.e., Western-style fast food) were more likely to develop overweight/obesity during follow-up, while those who were overweight/obese at baseline might change their eating behaviors with the intention of eating healthier (i.e., eat out less) during the follow-up in order to control their body weight. Results from our study will provide insight to promote healthy eating and childhood obesity prevention.

Methods and materials

Study design, study participants and data collection

The Childhood Obesity Study in China Mega-cities was designed as an open cohort study that aimed to study the etiology of childhood obesity in China. Children, their parents and schools in five major cities across China (Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Xi’an and Chengdu) were recruited and joined the study initiated in 2015. Thus far, data had been collected during November 2015, 2016 and 2017. Children were selected by stratified cluster sampling. In each city, two districts were randomly selected, then a primary schools (3rd–6th grades) and a middle schools (7th–9th grades) from each district were selected randomly.

These schoolchildren and their mothers or other key healthcare providers were surveyed using questionnaires, which contained rich information such as children’s health status, eating behaviors, physical activity and their home and school environments. Anthropometric measurements of children included height, weight, waist circumference and blood pressure were obtained by trained investigators.

Observations with missing data on related variables were excluded from the analysis. The final cross-sectional sample size for this analysis was 3313 school children (for those who had repeated measures during 2015–2017, only one measure was used in the analysis). For our longitudinal data analysis, children’s repeated measures collected during 2015–2017 were used (see below).

This study was approved by Ethical Committee of the State University of New York at Buffalo (FWA00008824) and related collaborative institutes in China. Written informed consents were collected from school administrators and parents and/or children.

Key variables and measurements

Eating-out behaviors

We measured eating-out behaviors using the frequency of eating out and the type of food consumed. The frequency of eating out was obtained from answers to the question, “How often (times/week) did you eat a meal or snack in the past 3 months?” The type of food consumed on these occasions was obtained by asking the number of times eating out in western-style restaurants (e.g., McDonald's, KFC, etc.) or in Chinese restaurants (including canteens and food stands) in the past 3 months. Eating out was categorized as yes or no. The frequency of eating out was categorized as 0, 1–2 and ≥ 3 times per week [24, 25].

Body weight status

Overweight, obesity and central obesity were key outcome variables. Height was measured without shoes using the Seca 213 Portable Stadiometer Height-Rod with a precision of 0.1 cm. Body weight was measured with light clothes using a Seca 877 electronic plate scale with a precision of 0.1 kg. Waist circumference was measured as midway between the highest point of the iliac crest and the bottom of the ribcage by an inelastic tape with an accuracy of 0.1 cm. Children’s body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2. Waist height ratio (WHtR) was calculated as = waist circumference (cm)/height (cm).

Obesity and overweight were defined using the Working Group on Obesity in China (WGOC) age-sex-specific BMI cutoffs, which were developed based on age-sex-specific BMI curves that correspond to BMI cutoffs of 24 (for overweight) and 28 (for obesity) at age 18 [26]. Central obesity was defined as WHtR ≥ 0.48 for children [27]. BMI cutoffs of 24 and 28 were used to define overweight (24 ≤ BMI < 28) and obesity (BMI ≥ 28) for parents.

Other covariates

Children’s pocket money was determined by asking “On average, how much pocket money do you receive from your family every week?”. Sex, age, city (Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Xi’an and Chengdu), school level (primary or middle school), father’s and mother’s BMI (kg/m2, calculated from self-reported weight and height) were collected. Data on frequency of parental eating-out behaviors per week and frequency of family eating-out per week, which were collected in the surveys, were also considered in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Cross-sectional data analysis

First, characteristics of the study participants were described based on cross-sectional (pooled) data collected from the children and their parents in 2015, 2016 and 2017. Only data collected from 1 year were used in this descriptive table for each subject (n = 3313). For those who participated twice or more, the earlier year data were used. Continuous variables were presented as means (standard deviation, SD), and categorical variables were presented as count and percentage. Chi-square and t test were conducted to compare between-group differences. Then, we assessed frequency of eating out, food type eaten and weight status (overweight, obesity and central obesity) in children by school type, city and gender. Third, multiple logistic regression models were used to identify factors associated with children’s eating-out behaviors (frequency and food type eaten). Eating-out behaviors were studied as the outcome variable.

Longitudinal data analysis

Mixed effect models were fit using the longitudinal data collected during 3 years to examine the associations between eating-out behaviors and overweight/obesity during follow-up among children who were not overweight/obesity at baseline (those being overweight/obese at baseline were excluded in this analysis) (n = 1089). Incidence of overweight/obesity was entered as dependent variable in this model.

Furthermore, we tested children’s eating-out behaviors among those who were overweight/obese at baseline vs. those who were not to investigate how baseline weight status might have affected eating behaviors during the follow-up (n = 1440). The frequency of eating-out behavior was entered as dependent variables. We tested whether those who were overweight/obese at baseline would have changed their eating-out behaviors during the follow-up period (e.g., eating out less to control body weight) than those who were not overweight/obese at baseline.

For both above analyses, we set school and individuals as fixed factors. We adjusted children’s factors including demographic factors (age, sex, city) and social economic factors (school levels and monthly pocket money) and parental factors (parental BMI, frequency of eating-out behaviors and eating out with family per week) as covariates for both analyses. We used the first measure if subjects had repeated measures for some of these covariates. As Western- and Chinese-style food were the two main types of eating-out food, and choosing of either type of food was not exclusive, so we presented the stratification by food style in these modes.

All statistical analysis was performed using Stata software (version 15.0). A two-tailed test and a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analysis.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study subjects. The combined prevalence of overweight/obesity and the prevalence of central obesity were 29.8% and 20.1%, respectively. Boys were more likely to be overweight and obese than girls (37.9% vs.21.3%, 16.7% vs. 8.5%, p < 0.001). Compared with girls, boys had higher WC, WHtR and central obesity (28.3% vs. 11.4%). Regarding to parental characteristics, girls’ mother had higher BMI than boys’ (p < 0.05).

Prevalence of eating-out behaviors in children

Table 2 shows that 80.1% of school children reported eating out at least once per week in previous 3 months, and 46.7% reported dining out on Western-style food. There were significant differences in eating out for Western-style food between primary school and middle school children (p < 0.001), between boys and girls (p < 0.001) and among children living in different cities (p < 0.001). 70.9% of school children reported they ate out on Chinese-style food at least once a week, with no difference by gender (p = 0.164). More boys ate out frequently (either for Chinese- or Western-style food) than girls (5.0% of boys consumed Western-style food ≥ 3 times per week vs. 3.5% of girls; 33.8% of boys consumed Chinese-style food ≥ 3 times per week vs. 28.8% of girls). Children in Chengdu had highest rate of consuming Chinese-style food among all five cities (80.2%), while those in Nanjing had highest percentage to eat out for Western-style food (51.7%, p < 0.001). The more frequently parents ate out themselves or with family, the more likely their children had eating-out behaviors (ptrend < 0.001).

Factors associated with children’s eating-out behaviors

Table 3 shows the factors that might be associated with children’s eating-out behaviors based on logistic regression analysis. Boys were more likely to choose Western-style food (OR 1.27; 95% CI 1.09–1.48) than girls. Age was positively associated with eating out for Chinese-style food (1.15; 1.06–1.24), but not for Western-style food. Children in Shanghai and Chengdu were more likely to choose Chinese-style food than those in Beijing (1.91; 1.45–2.53; 1.68; 1.29–2.20, respectively). Children whose parents ate out on their own (ate away from home ≥ 1 per week) were more likely to eat out than those whose parents never ate in a restaurant (1–2 times/week: 1.62; 1.19–2.21; ≥ 3 times/week: 1.60, 1.13–2.29, respectively). In addition, children whose parents ate out with their families at least once per week was more likely to eat out compared with those whose parents never ate in a restaurant.

Associations between children’s eating-out behaviors and weight status

Table 4 shows the associations between eating-out behavior at baseline and the incidence of overweight (during follow-up, as an outcome variable) among children who were not overweight/obese at baseline. Among the 1089 children who were not overweight/obese at baseline, 10.8% of them developed overweight during the follow-up period. Both eating out for Western-style and for Chinese-style food were not statistically significant associated with overweight risk after adjusting for child and parental factors.

How children’s weight status impact their eating-out behaviors?

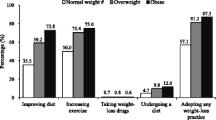

The further mixed model analysis showed that compared to children who were not overweight/obese at baseline, the overweight/obese children were less likely to have eating-out behaviors involving dining on Western-style food during the follow-up [OR and 95% CI 0.55 (0.40–0.75)]. The difference was greater in girls than in boys [0.42 (0.25–0.71) vs. 0.65 (0.45–0.95), respectively]. There were no such differences for consumption of Chinese-style food (Table 5). In addition, all the children’s eating-out behaviors increased as they grew older during follow-up. However, differences in this behavioral change occurred according to their baseline weight status. The non-overweight/obese children increased their consumption of Western-style food, while the overweight/obese children increased their consumption of Chinese-style food (Fig. 1).

Proportions (%) and trends of children’s eating-out behaviors at baseline and follow-up by their weight status (overweight vs. non-overweight) at baseline. a Eating out for Western-style food ≥ 1 times per week in the past 3 months. b *Eating out for Chinese-style food ≥ 2 times per week in the past 3 months. c #Eating out for Chinese-style food ≥ 3 times per week in the past 3 months

Discussion

Using data from five major cities across China, we examined the patterns of children’s eating-out behaviors, the associated factors and the relationship of these factors with the children’s obesity status. This is the first study to examine these issues using data collected from a large sample of school children and their parents across China. Overall, we found that eating out was common (80.1%) among Chinese school children, but there were considerable differences across groups. We also found a link between eating out and overweight/obesity status. Children who were overweight/obese at baseline were less likely to eat out for Western-style food than these who were free of overweight/obesity.

We defined eating out as having meals prepared and eaten in a Western- or Chinese-style restaurant or Chinese food stall, since these two types of food are the most common food that subjects consume. We found that 80.1% of these children reported having eating out at least once per week, with the figure being 46.7% and 70.9% for Western- and Chinese-style food, respectively. Boys, older children, those with more pocket money, and those whose parents ate out alone frequently were more likely to eat out than their counterparts. Parental eating-out behavior was a strong predictor of children’ eating out.

Boys were more likely to dine out on Western-style foods, while older children tended to dine out on Chinese-style food. There were significant differences in children's eating-out behaviors across cities, which may be due to some differences in economic development and food preference. In addition, we found that with the increase in pocket money, the frequency of eating out increased. This is consistent with our previous research which reported a positive relationship between pocket money and childhood overweight and obesity [23].

In addition, it is interesting to note that we found all the children’s eating-out behaviors increased as they grew older during the follow-up period, regardless of their baseline weight status. However, differences in the change existed according to their baseline weight status. The non-overweight/obese children increased their intake of Western-style food, while overweight/obese children increased their intake of Chinese-style food. Mixed model analysis shows that compared to children who were not overweight/obese at baseline, the overweight/obese children were less likely to have eaten out on Western-style food during the follow-up [OR and 95% CI 0.55 (0.40–0.75)], with the difference greater in girls than in boys, 0.42 (0.25–0.71) vs 0.65 (0.45–0.95), respectively. It is speculated that the awareness among some overweight/obese children, especially among girls, of the effect of Western-style food on obesity risk, and they attempted to limit their consumption of such food to help control their body weight.

With the rapid economic development in China over the past two decades, these five cities have experienced many remarkable shifts in their urban environment and residents’ lifestyles. The number of restaurants, including fast food restaurants, has increased rapidly [28]. Changes in the food environment have led to a rise in food consumption away from home. Between 2000 and 2008, the spending on food eaten away from home increased from 14.7 to 20.6% [29]. Another earlier study reported that 17.2% of children reported eating Western-style food at least once a month in 2004 [30], while in 2015, 51.9% of the children reported eating Western-style food at least once a week and 43.6% reported eating Chinese-style food at least once a month [9]. These findings are consistent with ours.

There are concerns regarding eating-out behaviors considering the kinds of food people may consume. Evidence from some systematic reviews reported that eating outside the home was associated with a higher total energy intake and higher percentage of energy from fat [7]. This is due to the fact that restaurant meals tend to have larger portion sizes and contain high energy density, fat, saturated fat, trans-fat, added sugar and sodium, all of which may increase the risks of obesity and other chronic disease [31,32,33,34]. However, studies investigating the frequency of eating out and the types of food consumed among children are limited.

One previous study showed that eating out more than twice a week was positively correlated with obesity in Hong Kong [35]. A Turkish study indicated that children’s eating behaviors were related to BMI without gender differences [36]. However, the present study did not show a significant association between eating-out behaviors and weight status.

Some limitations of this study need to be considered when interpreting our results. First, some of our analysis is based on cross-sectional data. Thus, the causal relationship between eating out and obesity could not be obtained. Second, our survey mainly asked about children’s eating-out behaviors in terms of number of times eating in a restaurant or at a stallholder, and this might not capture the effect of having the ability to order foods online for delivery to the home, which has become increasingly common in China in recent years. Third, information on co-variables, such as physical activities, snack eaten, which might have impact on results were lacking. Fourth, the study participants were 7- to 16-year-old children in five mega-cities, which do not represent other groups in China. Thus, the results cannot be generalized to all children in China. However, our open cohort study collected longitudinal data, and we used mixed models in data analysis. Cohort studies with a longer follow-up time are needed to confirm the causal relationship between eating out and overweight/obesity risks and to assess the differential effects of Chinese-style and Western-style food on childhood obesity.

In conclusion, eating out has become increasingly common among Chinese children and their parents living in large cities in China. These children increased the frequency of eating out over time. Over 80% of the children ate out at least once per week, while nearly half of them (46.7%) ate in Western-style restaurants. Boys, older children, those with more pocket money, and those whose parents ate out alone (without their families present) more often were more likely to eat out frequently than their counterparts. Parental eating-out behaviors were a strong predictor of their children’s eating-out behaviors. Children’ eating-out behaviors are associated with their obesity status in a bidirectional relationship. Nutrition and health education efforts are needed to empower children and their parents to make healthy food choices, especially when they eat away from home. National programs are recommended to promote restaurants to provide healthy dish choices. Such programs are needed to promote healthy eating in China, which will help fight the growing obesity and chronic disease epidemic.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Wang Y, Wang L, Xue H et al (2016) A review of the growth of the fast food industry in China and its potential impact on obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13(11):112

Xue H, Wu Y, Wang X et al (2016) Time trends in fast food consumption and its association with obesity among children in China. PLoS ONE 11:e0151141

Wang Y, Lobstein T (2006) Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes 1:11–25

An R, Yan H, Shi X et al (2017) Childhood obesity and school absenteeism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 18:1412–1424

Sun H, Ma Y, Han D et al (2014) Prevalence and trends in obesity among China’s children and adolescents, 1985–2010. PLoS ONE 9:e105469

Llewellyn A, Simmonds M, Owen CG et al (2016) Childhood obesity as a predictor of morbidity in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 17:56–67

Lachat C, Nago E, Verstraeten R, Roberfroid D, Van Camp J, Kolsteren P (2012) Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes Rev 13(4):329–346

Rosenheck R (2008) Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obes Rev 9:535–547

Young LR, Nestle M (2007) Portion sizes and obesity: responses of fast-food companies. J Public Health Policy 28:238–248

Torbahn G, Gellhaus I, Koch B et al (2017) Reduction of portion size and eating rate is associated with BMI-SDS reduction in overweight and obese children and adolescents: results on eating and nutrition behaviour from the observational KgAS Study. Obes Facts 10:503–516

Jia X, Liu J, Chen B et al (2018) Differences in nutrient and energy contents of commonly consumed dishes prepared in restaurants v. at home in Hunan Province. China Public Health Nutr 21:1307–1318

Wang Y, Mi J, Shan XY et al (2007) Is China facing an obesity epidemic and the consequences? The trends in obesity and chronic disease in China. Int J Obes (Lond) 31:177–188

National Bureau of Statistics (2008) Summary of Chinese statistics

Jia P, Li M, Xue H et al (2017) School environment and policies, child eating behavior and overweight/obesity in urban China: the childhood obesity study in China megacities. Int J Obes (Lond) 41:813–819

Zeng Q, Zeng Y (2018) Eating out and getting fat? A comparative study between urban and rural China. Appetite 120:409–415

Jiang Y, Wang J, Wu S, Li N, Wang Y, Liu J et al (2019) Association between take-out food consumption and obesity among Chinese university students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 16(6):1071

Cao K, He Y, Yang X (2014) The association between eating out of home and overweight/obesity among Chinese adults. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 48(12):1088–1092

Bezerra IN, Curioni C, Sichieri R (2012) Association between eating out of home and body weight. Nutr Rev 70(2):65–79

Dubois L, Farmer A, Girard M et al (2008) Social factors and television use during meals and snacks is associated with higher BMI among pre-school children. Public Health Nutr 11:1267–1279

Gable S, Chang Y, Krull JL et al (2007) Television watching and frequency of family meals are predictive of overweight onset and persistence in a national sample of school-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc 107:53–61

Magriplis E, Farajian P, Panagiotakos DB et al (2019) The relationship between behavioral factors, weight status and a dietary pattern in primary school aged children: the GRECO study. Clin Nutr 38:310–316

Magriplis E, Farajian P, Risvas G et al (2015) Newly derived children-based food index. An index that may detect childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Food Sci Nutr 66:623–632

Li M, Xue H, Jia P et al (2017) Pocket money, eating behaviors, and weight status among Chinese children: the Childhood Obesity Study in China mega-cities. Prev Med 100:208–215

Zhao Y, Wang L, Xue H et al (2017) Fast food consumption and its associations with obesity and hypertension among children: results from the baseline data of the Childhood Obesity Study in China Mega-cities. Bmc Public Health 17:933

Orfanos P, Naska A, Trichopoulos D et al (2007) Eating out of home and its correlates in 10 European countries. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Public Health Nutr 10:1515–1525

Ji CY (2005) Report on childhood obesity in China (1)–body mass index reference for screening overweight and obesity in Chinese school-age children. Biomed Environ Sci 18:390–400

Meng LH, Mi J, Cheng H et al (2008) Using waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio to access central obesity in children and adolescents. Chin J Evid Based Pediatr 3:324–325

Wang Y, Wang L, Xue H et al (2016) A review of the growth of the fast food industry in china and its potential impact on obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13:1112

Zhai FY, Du SF, Wang ZH et al (2014) Dynamics of the Chinese diet and the role of urbanicity, 1991–2011. Obes Rev 15(Suppl 1):16–26

Zhang YR, Wang JZ, Xue Y (2014) Investigation on relevant factors of eating out and fast food and overweight/obesity among 3–12-year-old children in 9 areas of China. China Maternal Child Health Care 29:5132–5135

Schroder H, Fito M, Covas MI (2007) Association of fast food consumption with energy intake, diet quality, body mass index and the risk of obesity in a representative Mediterranean population. Br J Nutr 98:1274–1280

Paeratakul S, Ferdinand DP, Champagne CM et al (2003) Fast-food consumption among US adults and children: dietary and nutrient intake profile. J Am Diet Assoc 103:1332–1338

Kris-Etherton PM, Lefevre M, Mensink RP et al (2012) Trans fatty acid intakes and food sources in the US population: NHANES 1999–2002. Lipids 47:931–940

Ma G (2004) Analysis of the relationship between the frequency of western fast food consumption and obesity rate of children and adolescents in four cities in China. J Nutr 6:486–489

Ko GT, Chan JC, Tong SD et al (2007) Associations between dietary habits and risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in a Hong Kong Chinese working population–the “Better Health for Better Hong Kong” (BHBHK) health promotion campaign. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 16:757–765

Sanlier N, Arslan S, Buyukgenc N et al (2018) Are eating behaviors related with by body mass index, gender and age? Ecol Food Nutr 57:372–387

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the study participants and the school personnel who participated in the study. We also thank those worked in the data collection and our collaborators from multiple institutes in China and the USA who have contributed to this study.

Funding

This study was funded in part by research grants from the National Institute of Health (NIH, U54 HD070725) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF2018-Nutrition-2.1.2.3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YW and JW conceived and designed the study. JZ, BX, LG, LZ and YW collected the data. JW, HX and YW analyzed the data and interpreted the results. JW prepared the manuscript, and YW, HX and LZ helped revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Ethical Committee of the State University of New York at Buffalo (FWA00008824) and related collaborative institutes in China. Written informed consents were collected from school administrators and parents and/or children.

Consent for publication

Written informed consents for publication were collected from parents and/or children.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, J., Gao, L., Xue, H. et al. Eating-out behaviors, associated factors and associations with obesity in Chinese school children: findings from the childhood obesity study in China mega-cities. Eur J Nutr 60, 3003–3012 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02475-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02475-y