Abstract

Growing evidence suggests that host-microbiota interactions influence GvHD risk following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. However, little is known about the influence of the transplant recipient’s pre-conditioning microbiota nor the influence of the transplant donor’s microbiota. Our study examines associations between acute gastrointestinal GvHD (agGvHD) and 16S rRNA fecal bacterial profiles in a prospective cohort of N=57 recipients before preparative conditioning, as well as N=22 of their paired HLA-matched sibling donors. On average, recipients had lower fecal bacterial diversity (P=0.0002) and different phylogenetic membership (UniFrac P=0.001) than the healthy transplant donors. Recipients with lower phylogenetic diversity had higher overall mortality rates (hazard ratio=0.37, P=0.008), but no statistically significant difference in agGvHD risk. In contrast, high bacterial donor diversity was associated with decreased agGvHD risk (odds ratio=0.12, P=0.038). Further investigation is warranted as to whether selection of hematopoietic stem cell transplant donors with high gut microbiota diversity and/or other specific compositional attributes may reduce agGvHD incidence, and by what mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The success of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) remains limited by GvHD. Even among transplants sourced from ‘gold standard’ donors (HLA-matched siblings), acute GvHD occurs in 35–45% of recipients,1, 2 highlighting the need to continue investigating GvHD etiology and new strategies for prophylaxis.

The 16S rRNA sequencing has enabled a dramatic re-evaluation of the relationships between GvHD and the intestinal bacteria.3, 4, 5 The pre-transplant microbiota of recipients has been reported to approximate the diverse microbiota compositions of healthy adults before transplant, but becomes dramatically altered following transplant procedures.6, 7, 8 The extent of this ‘disruption’ may contribute to GvHD: lower bacterial diversity9, 10, 11 and lower abundances of specific commensal bacteria like Blautia11 shortly after transplant have been associated with increased GvHD incidence and mortality. Mouse experiments further suggest a possible therapeutic benefit of post-transplant microbiome-based interventions: butyrate—one of many immunomodulatory short-chain fatty acids12 produced by commensal bacteria—mitigated GvHD when administered post transplant in mice.13

Mouse studies have also indicated that manipulation of the pre-transplant microbiota may have therapeutic potential: pre-transplant administration of Lactobacillus johnsonii14 and rhamnosus GG15 in mice resulted in decreased GvHD. Despite the promise of these experiments, the focus of most recent human studies has been the post-transplant time point,9, 10, 11, 16, 17 with relatively few studies profiling pre-transplant microbiota,6, 7, 8 even fewer sampling recipients prior to conditioning,7, 18 and of these, none reporting GvHD as the primary outcome. We hypothesized that pre-conditioning gut microbiota features in allo-HSCT recipients are associated with GvHD.

In addition, the influence of the stem cell donor’s microbiota on GvHD is unknown. Throughout the neonatal period and early life, the immune system establishes tolerance to ‘self’ through deletion of self-reactive cells or their differentiation into suppressive regulatory T cells. The nascent immune system similarly develops central and peripheral tolerance to the microbiota.19, 20 The tolerance that one individual’s immune system may have for the microbiota of another is unknown. We speculate that donor immune cell recognition of the transplant recipient’s intestinal microbiota as ‘non-self’ contributes to the immune response. Thus, we examined the hypothesis that acute gastrointestinal GvHD (agGvHD) is associated with dissimilarity in microbiota compositions between the allo-HSCT recipient and donor.

The donor’s microbiota may also influence GvHD through mechanisms independent of mismatch with the recipient’s microbiota. The intestinal bacteria and their products influence the activation and differentiation of immune cell populations like regulatory T cells.21, 22, 23 This influence occurs not only in the gut, but also in distant sites including the bone marrow.24, 25, 26 In principle, different donor microbiota may promote different compositions of transplanted allo-HSCT donor immune cells, consequently impacting alloreactivity and GvHD. We thus hypothesized that the composition and diversity of the donor microbiota itself is associated with GvHD.

To examine these three non-competing hypotheses, we used 16S rRNA gene sequencing to characterize fecal bacterial compositions in a pilot prospective cohort of allo-HSCT recipients and HLA-matched sibling donors at ‘baseline,’ defined respectively as 0–7 days before preparative conditioning for recipients and 0–7 days before administration of hematopoietic growth factors in donors. We explored associations between agGvHD incidence and (1) the diversity and relative abundance of taxa in the baseline recipient microbiota, (2) donor–recipient microbiota dissimilarity and (3) the diversity and abundance profiles of the donor microbiota.

Subjects and methods

Subject recruitment

We prospectively recruited allo-HSCT transplant recipients from the University of Colorado Hospital between 2012 and 2014. If the transplant was sourced from an HLA-matched sibling, we also recruited the stem cell donor. All donors met healthy standards per National Marrow Donor Program guidelines. Based on pre-established exclusion criteria, we did not analyze recipients without a baseline (pre-conditioning) fecal sample or clinical follow-up at +100 days or later (to identify most agGvHD cases). Ultimately, our study featured 57 recipients and 22 paired donors, a sample size that enables detection of high effect size microbiota associations (odds ratios (ORs) ⩾2.6 or ⩽0.38 with 80% power in the full recipient cohort; Supplementary File 1). The Multiple Institutional Review Board approved this study (COMIRB-12-1571). We obtained informed consent for all subjects.

Transplant regimen and diagnosis

Allo-HSCT recipients received chemotherapy±radiation prior to transfer of unmanipulated (that is, no T-cell depletion) hematopoietic stem cell graft sourced from a sibling, unrelated donor or two cord blood units (double cord). Low-intensity conditioning was most common: notably, low-dose TBI at 200 Gy with fludarabine±cytoxan. Each conditioning regimen was paired with one of four sets of GvHD prophylaxis medications: tacrolimus or cyclosporine with mycophenolate mofetil or methotrexate. The following antibiotics were used: Bactrim DS twice daily from day of admission to Day −2, levofloxacin 750 mg daily Day +1 until engraftment, and Bactrim DS twice daily, twice a week from Day +21 through 6 months.

GvHD was diagnosed clinically and graded per the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry criteria.27 Half of our agGvHD-positive diagnoses were also biopsied for confirmation. Further recipient characteristics and transplant outcomes are summarized in Table 1.

Sample preparation and sequencing

We modeled fecal sample collection after the Human Microbiome Project’s Core Microbiome Sampling Protocol A:28 within 24 h of the baseline clinical visit, subjects collected stool from a single bowel movement for storage in a provided cooler containing frozen gel packs. We homogenized stool samples with a metal spatula under sterile conditions and stored them at −80 °C until DNA extraction with the PowerFecal DNA Isolation kit (MO BIO Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA), using manufacturer protocols.

We performed broad-range amplification and sequencing of bacterial 16S rRNA genes with previously described methods.29, 30, 31 After normalizing each sample to ~106 template/microliter with quantitative PCR,32 we generated PCR amplicons with barcoded primers33 targeting the V4 hypervariable region of 16S rRNA (primers 534 F: 5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′ and 806 R: 5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). We sequenced resulting 16S amplicon libraries on the Illumina MiSeq using the 600-cycle MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The paired-end sequencing reads are available from the European Nucleotide Archive (accession ERP017899).

Bioinformatics pipeline

We translated sequencing reads into gut bacteria composition with QIIME34 v1.9.1. After filtering reads containing Phred scores <30 or chimeric sequences detected by USEARCH35 v6.1, we clustered forward reads into de novo operational taxonomic units36 at a 97% similarity threshold using UCLUSTref37 v1.2.22q and greengenes38 v13_8. We translated operational taxonomic units to taxa (for example, genus and species) using RDP39 v2.2. We constructed a phylogenetic tree of operational taxonomic units with FastTree40 v2.1.3, to evaluate bacterial diversity (phylogenetic diversity index,41 sums total phylogenetic branch length observed in a subject) and donor–recipient dissimilarities (unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances42 quantify unique versus shared phylogenetic tree branch length between two samples). These quantities were estimated from averages of 1,000 rarefactions at 70,490 reads/sample. Our bioinformatics analyses can be freely reproduced using Qiita (qiita.ucsd.edu/study/description/10564).

Statistical analysis

We tested for compositional differences between recipients and donors using the Welch t-test (for mean diversity, single taxa abundances) and permutational multivariate analysis of variance43 (multivariate UniFrac distribution; vegan44 R package v2.3-3). To quantify associations between agGvHD and the microbiota (diversity and taxa relative abundances), we modeled agGvHD as the outcome in multivariable logistic regression models (profile likelihood confidence intervals, likelihood ratio test P-values). Similarly, we used right-censored Cox proportional hazards regression (survival45 v2.38-3) to evaluate associations between overall mortality rate and the microbiota (post hoc; details in Supplementary File 2). Before statistical tests on taxa, we grouped operational taxonomic units at the species level and filtered species observed in fewer than 15% of subjects or <0.1% maximum relative abundance. Taxa relative abundances were log-transformed and scaled with the z-transformation to remove order of magnitude differences in interpreting ORs and hazard ratios.46

Regression models included adjustment for the following covariates: recipient age (years), obesity (body mass index ⩾30 versus <30), underlying disease (leukemia/other), donor sex-match (yes/no), donor CMV status (seropositive/seronegative or cord/cord), donor HLA-matched and related (yes/no), and conditioning intensity (low, reduced and high). At our center, conditioning intensity is paired with GvHD prophylaxis medication and stem cell source (PBSC, bone marrow and cord/cord); thus, we did not explicitly adjust for these two confounders due to collinearity. As particular antibiotics administered peri- and post transplant have been associated with GvHD,17, 47 we also performed a sensitivity analysis to examine whether including pre-transplant antibiotic exposures in models altered our conclusions (Supplementary File 4).

Results

Allo-HSCT recipients exhibit disrupted pre-conditioning microbiota

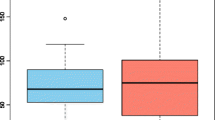

We observed substantial variability among baseline recipient microbiota compositions. Although the microbiota of some recipients resembled that of the healthy donors, lower bacterial diversity (Figure 1a; t-test, P=0.0002) and different phylogenetic membership (Figure 1b; permutational multivariate analysis of variance, unweighted UniFrac, P=0.001) were common. Namely, recipients had up to 97% relative abundances of facultative anaerobic bacteria (for example, Enterobacteriaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Enterococcaceae and Streptococcaceae) typical to early successional or disturbance-associated intestinal communities,48 in lieu of the obligate anaerobes (Bacteroidaceae, Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae) considered typical of the distal gut in healthy American adults49, 50 and observed in our donors (Figure 1c). In formal statistical tests, 58 species differed in average relative abundance between recipients and donors (Supplementary File 2).

Baseline microbiota composition differs between allo-HSCT recipients and healthy donors. (a) Bacterial diversity by group with superimposed median and interquartile ranges (IQRs). (b) Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) generated from unweighted UniFrac distance matrices in QIIME. (c) Heat map showing each subject’s observed log-transformed relative abundances for the top 20 most abundant taxonomic families and bacterial diversity. The dendrogram and order of the rows (taxa at the family resolution) was generated from unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Euclidean distance).

Baseline recipient diversity is associated with co-morbidities and mortality

As other centers6, 7, 8 have instead reported that the gut microbiota of recipients resemble those of healthy adults before transplant, we examined whether baseline recipient diversity was associated with baseline co-morbidities in our cohort. We were able to explain only 35% of the variation in recipient diversities using clinical information (R2 values; Supplementary File 4), but found lower diversities associated with more severe underlying hematologic disease (using conditioning intensity as a proxy for severity; analysis of variance P<1 × 10−4), CMV seropositivity (t-test; P=0.006), gastrointestinal and/or hepatic conditions (P=0.004), recent microbial infection (P=0.006) and pre-baseline antibiotic use (P=0.003; particularly antibiotics expected to be disruptive to the gut microbiota; see Supplementary File 4).

We also found one standard deviation increase in baseline recipient diversity to be associated with 60% lower overall mortality rates (Cox regression, P=0.008; hazard ratio=0.37, 95% confidence interval 0.18–0.77; causes of death summarized in Table 1). A significant association persisted after adjusting for the set of co-morbidities (absence/presence) described above. Supplementary File 2 describes these analyses and co-morbidity definitions in greater detail.

The baseline recipient microbiota and agGvHD

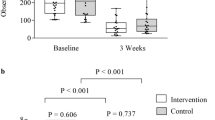

Recipient bacterial diversity was not significantly associated with agGvHD incidence (Figure 2a; P=0.28). Similarly, no taxa were significantly associated with agGvHD following multiple test correction, although this may follow from our low statistical power (see Supplementary File 1). Supporting this, taxa that trended with GvHD had large effect sizes (Table 2, and Figures 2b and c) and have been associated with HSCT outcomes in other studies8, 18 (see Discussion).

Associations between the baseline recipient microbiota and agGvHD incidence. Scatterplots with superimposed median and interquartile range (IQR) comparing (a) bacterial diversity and log-transformed relative abundances (RAs) of (b) P. distasonis and (c) Barnesiellaceae between agGvHD-negative and -positive recipients.

Baseline donor–recipient dissimilarity and agGvHD

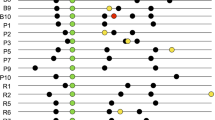

Among the N=22 ‘sub-cohort’ of transplant recipients whose HLA-matched sibling donor participated in the study, donor–recipient compositional dissimilarity was not significantly associated with agGvHD incidence (Figures 3a and b; unweighted and weighted UniFrac, P=0.36, P=0.88). However, due to the high variability in recipient microbiota but relative uniformity in donor profiles (Figure 1), UniFrac distances were strongly correlated with recipient diversity (Figures 3c and d), suggesting that UniFrac distances primarily indicated the recipient’s degree of microbiota disruption relative to the health profile. This analysis thus primarily reiterates the nonsignificant association between low recipient diversity and agGvHD.

Associations between donor-recipient dissimilarity (UniFrac distances) and agGvHD incidence. For the recipient sub-cohort with paired donor samples (N=22), we show (a) unweighted and (b) weighted donor-recipient UniFrac distances by agGvHD-negative and -positive recipients with superimposed median and IQR. (c and d) Scatterplots of UniFrac distances and recipient bacterial diversity. The Pearson correlations between diversity and donor-recipient UniFrac distances are respectively −0.68 and −0.64.

The baseline donor microbiota and agGvHD

An increase of 1 s.d. in baseline donor diversity was significantly associated with 88% lower odds of agGvHD in the corresponding transplant recipient (Figure 4a; P=0.038; OR=0.12, 95% confidence interval: 0.01–0.81). No donor taxa differentiated agGvHD incidence, although we note that 17 species were significantly correlated with donor diversity (Table 3), including disruption-associated taxa in HSCT recipients, like Enterococcus and Lactobacillus (Figure 4b).

Associations between donor microbiota and agGvHD incidence. (a) Scatterplot with superimposed median and interquartile range (IQR) shows association between high donor bacterial diversity and lower agGvHD odds. One donor associated with an agGvHD-negative recipient appears to have an outlying phylogenetic diversity (PD) value of 517, but the association between donor diversity and lower agGvHD odds remains significant with the putative outlier’s removal (resulting OR=0.20, P=0.049). (b) Spearman's correlations between bacterial diversity and taxa relative abundances, where blue indicates higher Spearman correlation (that is, taxa enriched in high diversity donors or recipients). Rows (taxa at the family resolution) were sorted by unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Euclidean distance).

Discussion

The baseline microbiota profiles of allo-HSCT donors, but not recipients, were significantly associated with agGvHD. Higher donor bacterial diversity was associated with decreased agGvHD risk (OR=0.12, P=0.038), an association potentially consistent with either of our two donor-centric hypotheses.

First, we hypothesized that donor-recipient microbiota dissimilarity at baseline would be associated with increased GvHD. Measuring donor–patient dissimilarity using UniFrac was uninformative, as UniFrac was primarily driven by the degree of recipient microbiota ‘disturbance,’ which was in turn not significantly associated with GvHD (Figure 3). However, this hypothesis may be supported by higher relative abundances of facultative anaerobes like Enterococcus and Lactobacillus among high diversity donors (Table 3). These species were often enriched in our recipients before conditioning (Figure 1) and expand following transplant procedures peri-engraftment and during GvHD onset.6, 14, 51 Thus, higher diversity donors may be more immunotolerant of the taxa characteristic of many allo-HSCT recipients.

The association between high donor diversity and decreased agGvHD risk is also supportive of our hypothesis that the donor’s microbiota may influence GvHD incidence through mechanisms independent of the recipient’s microbiota. This could occur if different donor microbiota promote different compositions and/or alloreactivities of transplanted immune cells. Interestingly, higher diversity donors harbored higher relative abundances of commensal bacteria with evidence for anti-inflammatory effects (Table 3), including bacteria associated with regulatory T cell differentiation (for example, Bacteroides fragilis22, 52 and Bifidobacterium spp.53). Pairing donor microbiota profiles with measurements of graft immune cell subsets or investigation of the immune modulatory activities of donor microbiota in vitro may yield more insight into this hypothesis.

To our knowledge, associations between the donor microbiome and GvHD have only previously been explored in mice. The absence/presence of a donor microbiota (that is, whether the donor mouse was germ-free) did not affect donor T-cell alloreactivity or GvHD severity.54 However, more nuanced features (for example, diversity and membership) were not evaluated. Moreover, the distorted immune system of germ-free mice22, 55 is of unknown generalizability to that of human donors, whose immune system is shaped by the microbiota throughout life.56 Alternatively, donors with more ‘permissive’ immune systems due to factors like host genetics57, 58 and early life exposures59, 60 (which may not vary among laboratory mice) may enable colonization by a greater variety of microbes. Thus, higher donor microbiota diversity may indicate higher donor immunologic tolerance.

Although the association between high donor diversity and lower GvHD risk remained significant after adjusting for measured donor-based risk factors (for example, CMV seropositivity and sex match), other donor traits (for example, age and obesity) were not collected and thus should be thoroughly examined in follow-up donor studies. However, regardless of the underlying mechanistic relationships (that is, even if not directly causal), donor diversity could be a useful indicator of a complex collection of GvHD risk factors.

In contrast, we did not find significant associations between the pre-conditioning microbiota of the allo-HSCT recipient and agGvHD, although four species trended with GvHD risk before multiple test correction (Table 2). We found the decreased GvHD risks associated with Parabacteroides distasonis (OR=0.28) and Barnesiellaceae spp. (OR=0.38) notable due to the underpowered nature of our pilot study (Supplementary File 1), large effect sizes, and biological rationale building on previous allo-HSCT and microbiome literature. In a pediatric allo-HSCT cohort, Parabacteroides was higher among GvHD-negative recipients and was correlated with fecal propionate concentrations.8 Pre-conditioning Barnesiellaceae predicted lower risk of chemotherapy-related bloodstream infection among an adult allo-HSCT cohort.18 In addition, both taxa have been associated with anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles (for example, decreases in TNF-α61, 62). The baseline microbiota may thus contribute immunomodulatory or mucosal integrity functions that reduce future GvHD risk. Conversely, taxa like Lachnobacterium spp. (OR=2.37) and Haemophilus parainfluenzae (OR=2.04)—which have not previously been reported in HSCT/microbiome literature—may be pro-inflammatory microbes that increase GvHD risk. Thus, associations between the pre-conditioning recipient microbiota and GvHD may merit further investigation in studies with higher power.

More generally, baseline recipient disruption—characterized by significantly lower diversity and lower relative abundances of obligate anaerobes compared with healthy donors (Figure 1)—may warrant exploration at other centers. In our recipients, baseline disruption was significantly associated with overall mortality rates (hazard ratio for diversity=0.37, P=0.008). In contrast, two previous 16S rRNA studies that sampled adult allo-HSCT recipients alongside healthy controls reported recipients to approximate the typical healthy adult profile,6, 7 despite similarly permissive inclusion criteria (for example, mixes of underlying hematologic diseases, no reported exclusion on recent antibiotic use or co-morbidities). However, given that low baseline diversity was associated with conditions common to many allo-HSCT recipients like pre-conditioning microbial infection and antibiotic use (Supplementary File 3), we suspect that our findings are generalizable to other centers.

These findings compliment pioneering studies observing improved recipient outcomes with less disrupted post-transplant microbiota, while also suggesting potential benefits of clinical interventions prior to conditioning. However, further studies at the pre-conditioning time point are needed to clarify the causes and clinical implications of baseline recipient disruption. The pre-conditioning microbiota may mediate the effects of existing gut decontamination practices or prospective prebiotic/probiotic treatments:63, 64 thus, fostering ‘protective’ microbiota compositions prior to admission may compliment later interventions on recipients’ intestinal bacteria. Thus, if observed in more centers, further study of baseline recipient disruption may lead to insight about the generalizability of and/or best practices for microbiome-targeted interventions in allo-HSCT recipients.

Our study also provides preliminary evidence for a previously undescribed GvHD risk factor: low microbiota diversity of the stem cell donor. However, our pilot study was limited in sample size and donor characteristics (N=22 HLA-matched siblings from a single center, unmanipulated graft and 21/22 PBSC). It is critical to reexamine this association in broader transplant settings—particularly as other populations (for example, recipients with no suitable ‘gold standard’ donor) may benefit most from new donor screening criteria. Moreover, while we have presented speculation on the mechanisms underlying the association between high donor diversity and decreased agGvHD risk, future investigations of the donor gut microbiota that aim to characterize causes of donor diversity and to integrate 16S rRNA data with immunological measurements may yield novel insights about the etiology of GvHD.

References

Ferrara JL, Levine JE, Reddy P, Holler E . Graft-versus-host disease. Lancet 2009; 373: 1550–1561.

Magenau J, Runaas L, Reddy P . Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of graft-versus-host disease. Br J Haematol 2016; 173: 190–205.

Murphy S, Nguyen VH . Role of gut microbiota in graft-versus-host disease. Leuk Lymphoma 2011; 52: 1844–1856.

Mathewson N, Reddy P . The microbiome and graft versus host disease. Curr Stem Cell Rep 2015; 1: 39–47.

Zama D, Biagi E, Masetti R, Gasperini P, Prete A, Candela M et al. Gut microbiota and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: where do we stand? Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 52: 1–8.

Holler E, Butzhammer P, Schmid K, Hundsrucker C, Koestler J, Peter K et al. Metagenomic analysis of the stool microbiome in patients receiving allogeneic stem cell transplantation: loss of diversity is associated with use of systemic Antibiotics and more pronounced in gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014; 20: 640–645.

Taur Y, Xavier JB, Lipuma L, Ubeda C, Goldberg J, Gobourne A et al. Intestinal domination and the risk of bacteremia in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55: 905–914.

Biagi E, Zama D, Nastasi C, Consolandi C, Fiori J, Rampelli S et al. Gut microbiota trajectory in pediatric patients undergoing hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015; 50: 992–998.

Taur Y, Jenq RR, Perales M-A, Littmann ER, Morjaria S, Ling L et al. The effects of intestinal tract bacterial diversity on mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2014; 124: 1174–1182.

Weber D, Oefner PJ, Hiergeist A, Koestler J, Gessner A, Weber M et al. Low urinary indoxyl sulfate levels early after ASCT reflect a disrupted microbiome and are associated with poor outcome. Blood 2015; 126: 1723–1729.

Jenq RR, Taur Y, Devlin SM, Ponce DM, Goldberg JD, Ahr KF et al. Intestinal blautia is associated with reduced death from graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015; 21: 1373–1383.

Corrêa-Oliveira R, Fachi JL, Vieira A, Sato FT, Vinolo MAR . Regulation of immune cell function by short-chain fatty acids. Clin Transl Immunol 2016; 5: e73.

Mathewson ND, Jenq R, Mathew AV, Koenigsknecht M, Hanash A, Toubai T et al. Gut microbiome-derived metabolites modulate intestinal epithelial cell damage and mitigate graft-versus-host disease. Nat Immunol 2016; 17: 505–513.

Jenq RR, Ubeda C, Taur Y, Menezes CC, Khanin R, Dudakov JA et al. Regulation of intestinal inflammation by microbiota following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Exp Med 2012; 209: 903–911.

Gerbitz A, Schultz M, Wilke A, Linde H-J, Schölmerich J, Andreesen R et al. Probiotic effects on experimental graft-versus-host disease: let them eat yogurt. Blood 2004; 103: 4365–4367.

Bilinski J, Robak K, Peric Z, Marchel H, Karakulska- Prystupiuk E, Halaburda K et al. The impact of gut colonization by antibiotic-resistant bacteria on the outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a retrospective, single-center study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016; 22: 1087–1093.

Shono Y, Docampo MD, Peled JU, Perobelli SM, Velardi E, Tsai JJ et al. Increased GVHD-related mortality with broad-spectrum antibiotic use after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in human patients and mice. Sci Transl Med 2016; 8: 339ra71–339ra71.

Montassier E, Al-Ghalith GA, Ward T, Corvec S, Gastinne T, Potel G et al. Pretreatment gut microbiome predicts chemotherapy-related bloodstream infection. Genome Med 2016; 8: 49.

Lathrop SK, Bloom SM, Rao SM, Nutsch K, Lio C-W, Santacruz N et al. Peripheral education of the immune system by colonic commensal microbiota. Nature 2011; 478: 250–254.

Cebula A, Seweryn M, Rempala GA, Pabla SS, McIndoe RA, Denning TL et al. Thymus-derived regulatory T cells contribute to tolerance to commensal microbiota. Nature 2013; 497: 258–262.

Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, Suda W, Nagano Y, Nishikawa H et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature 2013; 500: 232–236.

Round JL, Mazmanian SK . Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 12204–12209.

Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Hase K . Commensal microbiota regulates T cell fate decision in the gut. Semin Immunopathol 2015; 37: 17–25.

Khosravi A, Yáñez A, Price JG, Chow A, Merad M, Goodridge HS et al. Gut microbiota promote hematopoiesis to control bacterial infection. Cell Host Microbe 2014; 15: 374–381.

Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Yadava K, Sichelstiel AK, Sprenger N, Ngom-Bru C et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med 2014; 20: 159–166.

Josefsdottir KS, Baldridge MT, Kadmon CS, King KY . Antibiotics impair murine hematopoiesis by depleting intestinal microbiota. Blood 2017; 129: 729–739.

Rowlings PA, Przepiorka D, Klein JP, Gale RP, Passweg JR, Henslee-Downey PJ et al. IBMTR Severity Index for grading acute graft-versus-host disease: retrospective comparison with Glucksberg grade. Br J Haematol 1997; 97: 855–864.

McInnes P, Cutting M Manual of Procedures for Human Microbiome Project Core Microbiome Sampling Protocol A: HMP Protocol 7-001. Version 9.0. 2010,National Institutes of Health.

Lemas DJ, Young BE, Baker PR, Tomczik AC, Soderborg TK, Hernandez TL et al. Alterations in human milk leptin and insulin are associated with early changes in the infant intestinal microbiome. Am J Clin Nutr 2016; 103: 1291–1300.

Brumbaugh DE, Arruda J, Robbins K, Ir D, Santorico SA, Robertson CE et al. Mode of delivery determines neonatal pharyngeal bacterial composition and early intestinal colonization. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016; 63: 320–328.

Markle JGM, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S, Robertson CE, Feazel LM, Rolle-Kampczyk U et al. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science 2013; 339: 1084–1088.

Nadkarni M, Martin FE, Jacques NA, Hunter N . Determination of bacterial load by real-time PCR using a broad range (universal) probe and primer set. Microbiology 2002; 148: 257–266.

Frank DN . BARCRAWL and BARTAB: software tools for the design and implementation of barcoded primers for highly multiplexed DNA sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics 2009; 10: 362.

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Publ Gr 2010; 7: 335–336.

Edgar RC . Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010; 26: 2460–2461.

Westcott SL, Schloss PD . De novo clustering methods outperform reference-based methods for assigning 16 S rRNA gene sequences to operational taxonomic units. PeerJ 2015; 3: e1487.

Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R . UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011; 27: 2194–2200.

DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16 S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006; 72: 5069–5072.

Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR . Naïve Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007; 73: 5261–5267.

Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP . Fasttree: Computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol 2009; 26: 1641–1650.

Faith DP, Baker AM . Phylogenetic diversity (PD) and biodiversity conservation: some bioinformatics challenges. Evol Bioinform Online 2006; 2: 121–128.

Lozupone C, Knight R . UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 2005; 71: 8228–8235.

Anderson MJ, Walsh DCI . PERMANOVA, ANOSIM, and the Mantel test in the face of heterogeneous dispersions: what null hypothesis are you testing? Ecol Monogr 2013; 83: 557–574.

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB et al vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2016.

Therneau TM A Package for Survival Analysis in S. 2015.

Ramette A . Multivariate analyses in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2007; 62: 142–160.

Whangbo J, Ritz J, Bhatt A . Antibiotic-mediated modification of the intestinal microbiome in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 52: 183–190Online: 1–8.

Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, Jansson JK, Knight R . Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2012; 489: 220–230.

Donaldson GP, Lee SM, Mazmanian SK . Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol 2016; 14: 20–32.

Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 2012; 486: 222–227.

Weber D, Oefner PJ, Dettmer K, Hiergeist A, Koestler J, Gessner A et al. Rifaximin preserves intestinal microbiota balance in patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51: 1087–1092.

Troy EB, Kasper DL . Beneficial effects of Bacteroides fragilis polysaccharides on the immune system. Front Biosci 2010; 15: 25–34.

López P, González-Rodríguez I, Gueimonde M, Margolles A, Suárez A . Immune response to Bifidobacterium bifidum strains support Treg/Th17 plasticity. PLoS ONE 2011; 6: e24776.

Tawara I, Liu C, Tamaki H, Toubai T, Sun Y, Evers R et al. Influence of donor microbiota on the severity of experimental graft-versus-host-disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013; 19: 164–168.

Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell 2009; 139: 485–498.

Gensollen T, Iyer SS, Kasper DL, Blumberg RS . How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 2016; 352: 539–544.

Blekhman R, Goodrich JK, Huang K, Sun Q, Bukowski R, Bell JT et al. Host genetic variation impacts microbiome composition across human body sites. Genome Biol 2015; 16: 191.

Goodrich JK, Waters JL, Poole AC, Sutter JL, Koren O, Blekhman R et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell 2014; 159: 789–799.

Arrieta MC, Stiemsma LT, Amenyogbe N, Brown EM, Finlay B . The intestinal microbiome in early life: health and disease. Front Immunol 2014; 5: 427.

Tamburini S, Shen N, Wu HC, Clemente JC . The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes. Nat Med 2016; 22: 713–717.

Kverka M, Zakostelska Z, Klimesova K, Sokol D, Hudcovic T, Hrncir T et al. Oral administration of Parabacteroides distasonis antigens attenuates experimental murine colitis through modulation of immunity and microbiota composition. Clin Exp Immunol 2011; 163: 250–259.

Dinh DM, Volpe GE, Duffalo C, Bhalchandra S, Tai AK, Kane AV et al. Intestinal microbiota, microbial translocation, and systemic inflammation in chronic HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2015; 211: 19–27.

Andermann TM, Rezvani A, Bhatt AS . Microbiota manipulation with prebiotics and probiotics in patients undergoing stem cell transplantation. Curr Hematol Malig Rep 2016; 11: 19–28.

Peled JU, Jenq RR, Holler E, van den Brink MRM . Role of gut flora after bone marrow transplantation. Nat Microbiol 2016; 1: 16036.

Acknowledgements

We thank our study participants and clinical staff. We thank Jørgen V Bjørnholt, Merete Eggesbø, and Tore Midtvedt for use of their antibiotic classification scale in our sensitivity analysis and thank Keith Hazleton for consulting on antibiotic classifications. We are grateful for our anonymous peer reviewers for their feedback on our manuscript. This research was generously supported by the Amy Strelzer Manasevit Research Program and Denver Golfers Against Cancer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Bone Marrow Transplantation website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, C., Frank, D., Horch, M. et al. Associations between acute gastrointestinal GvHD and the baseline gut microbiota of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients and donors. Bone Marrow Transplant 52, 1643–1650 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2017.200

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2017.200

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

The gut microbiome: an important factor influencing therapy for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Annals of Hematology (2024)

-

The association of intestinal microbiota diversity and outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Annals of Hematology (2023)

-

Microbiota long-term dynamics and prediction of acute graft-versus-host disease in pediatric allogeneic stem cell transplantation

Microbiome (2021)

-

Roles of the intestinal microbiota and microbial metabolites in acute GVHD

Experimental Hematology & Oncology (2021)

-

Patterns of infection and infectious-related mortality in patients receiving post-transplant high dose cyclophosphamide as graft-versus-host-disease prophylaxis: impact of HLA donor matching

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2021)