Abstract

The adoption of trauma-informed practices in schools is a significant and growing area of school reform efforts. It has been assumed that professional development aimed at influencing teacher attitudes toward trauma-informed care in schools is an important first step in adopting trauma-informed practices and improving student and school outcomes. However, there are gaps in the literature assessing the impact of trauma-informed professional development on teacher attitudes toward trauma-informed care, and there is little evidence linking changes in teacher attitudes to changes in practices. This exploratory study assessed teacher responses to a year-long pilot program providing intensive professional development and consultation on trauma-informed practices in one urban elementary school in the U.S. Southwest. Findings raise questions about the impact of professional development on teacher attitudes and subsequent changes to practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Trauma-informed practices in schools have become a significant focus for school reform and educator professional development over the last decade [25] While a significant body of work has established the need for trauma-informed approaches and established their theory of impact [33], empirical evidence documenting positive outcomes for the systemic application of trauma-informed practices is limited [21]. There is also limited research into the impact of trauma-informed professional development on teacher attitudes toward trauma-informed care [4, 8]. Well-intentioned policies or programs requiring teachers to receive training on the impact of trauma have led to the tendency to conflate having received training on trauma or trauma-informed practice with actual implementation of these practices [23]. Furthermore, there is significant variability in the content of and approaches to professional development and the need for a more systematic, research-based approach to addressing gaps in teacher knowledge [33].

This study documents preliminary findings from a year-long program involving intensive trauma-informed professional development and consultation on teacher attitudes toward trauma-informed care and their perspectives on the impact of professional development in one elementary school. The program was designed by the researchers in consultation with current literature [10] existing models [11, 12] and school administration to effectively apply evidence-based frameworks for trauma-informed practices to this setting. Data were collected from participating teachers before and after the program to answer the research questions: (1) What is the impact of intensive professional development and ongoing consultation around trauma-informed practices on teacher attitudes toward trauma-informed care, and (2) How do teachers describe the impact of this approach to professional development on their attitudes, their own practices, their school’s practices/policies, or the school environment?

1.1 Literature review

In the United States and across the globe, trauma-informed practices are increasingly acknowledged as critical approaches to intervention and school reform which seek to address the pervasive impacts of trauma on child development, school functioning, and academic achievement [9, 16]. The widespread attention to these approaches has significant implications for training and professional development of teachers who are primary implementors of these practices. By 2017, at least eleven states had mandated some form of trauma education or training for school staff [32] and this number continues to increase. Additionally, there has been a shift from a strong focus on identifying students who have experienced trauma and the provision of trauma-specific interventions toward frameworks that focus on whole-school structures and changes to classroom and school practices and policies to prevent and respond to trauma [8, 28, 32, 36]. These realities have significant implications for teacher professional development in trauma-informed practices. While efforts to provide professional development that supports implementation of such schoolwide efforts have proliferated, research has struggled to catch up.

In identifying research for this review, the authors completed a comprehensive search of their library databases for peer-reviewed articles published after 2010 using the terms “trauma-informed” and “teacher” and either “training” or “professional development”. This yielded 306 articles which were then limited to those which presented novel data from pk-12 teachers assessing the impact of approaches to professional development in this area. Theoretical articles or articles exploring practitioners in other settings constituted most articles in the initial search with fewer than ten articles meeting the above criteria. In addition, the authors consulted several existing systematic reviews relating to trauma-informed practices in pk-12 education [1, 2, 4, 21, 33,34,35] to identify any additional research not identified in the original search. Of those articles reviewed, most focused on teacher perceptions of training, fewer assessed the relationship between professional development and practice. Several also described a positive response to training inhibited by barriers to implementation such as Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS). We describe this body of research below.

1.2 Impact of professional development on knowledge, attitudes, perceptions, and practices

In one of the largest and most comprehensive studies of the impact of trauma-informed professional development, McIntyre and colleagues [22] evaluated teachers’ attitudes towards a two-day “Foundational Professional Development (FDP)” (p. 95) program. Their sample of 185 teachers from six different schools demonstrated significant growth in teacher knowledge about trauma and its impact based on a pre-post assessment. They also found that support for trauma-informed approaches was higher in participants who reported fit between these approaches and their existing school systems [22].

Parker and colleagues [26] described two evaluations of the impact of Compassionate Schools Training (CST) on teacher participants. In a questionnaire assessing teacher mindset and self-reported behavior changes related to trauma-informed practices administered six months after training, 74% of 133 participants reported changes in both their mindset and behavior and 86% reported persistent changes in their mindset post-training. A second evaluation of the training came from administration of the ARTIC (Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care) directly before and after participation in CST. Participants demonstrated a significant increase in positive attitudes toward trauma-informed care in schools overall and on each sub-scale within the ARTIC. Another study by Stipp and Kilpatrick [31] evaluated a six-session teacher training based on the Trust-Based Relational Intervention (TBRI) system, noting that the forty-one participants responses indicated that the training was “valuable” and “socially acceptable”.

While the studies described above addressed in-service teachers, other research has focused on pre-service educators. Rodger and colleagues [29] assessed the impact of integrating principles of Trauma and Violence Informed Care (TVIC) into a mental health literacy course in an undergraduate teacher preparation program in Canada. Among the 287 participants, it was reported that the course significantly increased positive attitudes toward TVIC as well as self-reported efficacy in teaching using inclusive practices.

In a more direct evaluation of the relationship between training, teacher knowledge of trauma and their ability to respond to students impacted by trauma, Sonsteng-Person and Loomis [30] evaluated survey responses from ninety-four teachers in Los Angeles. Rather than assessing outcomes from a specific program, the authors used regression to analyze the relationship between teacher self-report of participation in trauma-specific training, their knowledge of trauma (measured by the Teaching Traumatized Students Scale) and their difficulty responding to students (measured by the Teachers’ Difficulties Helping Children after Traumatic Exposure Scale). Findings indicated that training did increase knowledge of trauma and that this mediated teacher reported difficulty in responding to students impacted by trauma.

Other research has documented the impact of more structured and expansive approaches to professional development in trauma-informed practices using quasi-experimental design. An evaluation of the effectiveness of Child-Teacher Relationship Training (CTRT) by Post and colleagues [28] compared perspectives on trauma-informed practices from a group of teachers who participated in CTRT with a control group who did not participate. The intervention group showed significant growth in favorable attitudes towards trauma-informed care and growth in their use of trauma-informed practices in the classroom setting although no impact on their professional quality of life (compared with the control group) were observed. Overall, findings suggested that training was effective but did not address sustainability of trauma-informed practices due to the impact of Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) on teachers. This and other barriers to implementation that inhibit the efficacy of training are more fully explored below.

1.3 Inhibiting factors

Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) describes trauma-related symptoms resulting from interactions with the traumatic experiences and trauma responses of others [24]. Teachers may experience STS when they learn about the traumatic experiences of students or witness trauma’s impact on students. As a profession, teachers generally report high levels of STS [20], which adversely impact their personal and professional functioning, especially for educators in marginalized communities [14, 19]. Given the identification of Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) as an inhibiting factor, additional work that specifically addresses teacher experiences of trauma within trauma-informed professional development has emerged.

An approach known as Enhancing Trauma Awareness (ETA) [12], was evaluated by Herman and Whitaker in 2020 [18]. ETA involves six sessions over a 12-week period, which utilize a group-based, relational approach to increasing teacher knowledge and skills. This approach varies from others in its emphasis on participant exploration of their own traumas and experiences as a way of learning how to acknowledge and work with students who experienced trauma. Participants demonstrated growth in empathy, self-regulation, and mindfulnesshighlighting the potential value of a more holistic and experiential approaches to training when compared with other similar studies. In another application of approaches oriented toward addressing teacher trauma, Castro Schepers and Young [7] described the positive impact of pre-services educators’ participation in a trauma-informed practice seminar on preventing or decreasing experiences STS in this population.

In addition to the specific impact of STS, more generalized experiences of stress, lack of support, and challenges with school climate likely interfere with the translation of professional development into practice. Anderson and colleagues [1] described results of a study in which sixteen teachers participated in four workshops addressing the impact of trauma on students and supportive school-based responses. Participants demonstrated increased knowledge about and understanding of trauma in addition to identifying tangible takeaways from the trainings. However, data suggested that training did not significantly influence practices. Several potential barriers to implementation were identified by participants in focus groups. These included experiences of stress in the school climate, lack of support to work with students impacted by trauma and teacher lack of power/authority in the school. This work highlights the significant interaction between the school as a system and the potential for changes to teacher practices as a critical determining factor in the ultimate efficacy of professional development.

1.4 Synthesis

Taken as a whole, research suggests that a wide range of approaches are effective at increasing teacher knowledge about and positive attitudes toward trauma-informed practices. However, most evaluations of teacher attitudes toward trauma-informed care reflect changes immediately post-training and may not be reflective of the durability of these changes. While Parker and colleagues [26] sought to assess changes six months after training, their participants had self-selected to participate in training as individuals which may or may not reflect expected changes in the general population of teachers who might be required in such training as part of broader school reform efforts.

Emergent research also suggests that training and subsequent changes in knowledge or attitudes could increase teacher ability to effectively respond to trauma-related needs in students. However, other research suggests that even positively received and effective training may not translate into changes in teacher practices and that changes in practice lag changes in knowledge/attitudes. Importantly, barriers to implementation also impact training efficacy. Several studies described teacher stress (due to STS or general issues in school climate) as a factor inhibiting translation of training to practice while another asserted the importance of fit between training and existing structures and systems.

The current study sought to contribute to current research by assessing changes in teacher attitudes related to trauma-informed care in schools resulting from whole-school professional development and consultation over the course of an academic year. This specific approach to professional development utilized recommend practices and address barriers identified in existing literature. Below, we describe our project design and study results, situating them within the broader conversation around the demonstrated and potential impact of trauma-informed professional development for teachers.

1.5 Theoretical framework and project design

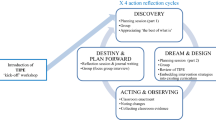

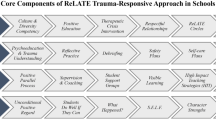

The approach to professional development used in the current case study utilized Borko’s model of integrated cognitive and social approaches to teacher professional development [6] in trauma-informed practice and assessed the impact of such a model on teacher attitudes toward trauma-informed care over one year. Employing methods based on the Enhancing Trauma Awareness approach (ETA) described by Herman and Whitaker [18] professional development activities involved teacher self-reflection, group processing and opportunities for modeling or practicing trauma-informed responses. These occurred in both the initial four-hour workshop and subsequent sessions that were co-designed by school leaders and the researcher.

This project also employed guidance from the Trauma and Learning Policy Institute [10], which emphasizes that trauma-informed practices require a whole school effort and that the specific manifestations of these practices are and should be school-specific to meet the unique needs of students and communities. In these efforts, the researcher participated in school leadership meetings relating to the revision of school discipline and support policies and practices the summer prior to project implementation. The researcher also participated in the school’s community school council which involves staff, students, administrators, family, and community members.

These efforts resulted in a collaboratively designed year-long professional development plan, coordinated to support additional policy changes within the school system. In the summer prior to the trauma-informed development project, all school staff participated in summer sessions designed to create multi-tiered, supportive responses to student behavior challenges. This included defining schoolwide expectations and positive supports, distinguishing classroom versus office responses to behavioral concerns, and identifying tier 2 and 3 supports in response to behavioral needs at the school level. The researcher co-participated in these sessions and utilized outcomes to inform trauma-informed professional development.

Prior to students returning to school, all teachers participated in a 4-h initial training which provided foundational information on the impact of trauma and trauma-informed practices in schools provided by the researcher. The researcher returned for two subsequent one-hour professional development sessions, co-designed by the researcher, school administrators, and teacher-leaders in the school to respond to specific and emerging staff and student needs. Specific areas of focus include trauma-informed family engagement, self-regulation for educators, and self and community care for staff.

The researcher also provided monthly office hours” orpláticas following professional development sessions in which they met with teachers and staff informally to discuss challenges and needs relating to areas of focus. Pláticas are “both a method and a methodology” focused on dialogue which typically include making initial connections between the interviewer and interviewee, an interview which involves both informal conversation and information gathering, and a closing which can involve sharing of gifts or other more personal connections [13]. In the context of this project, the researcher regularly set up in the teachers lounge with tea or pastries from a local panaderia and invited staff to stop by, share challenges, and ask questions. These dialogues served as opportunities for data gathering, relationship building, and providing support. This involved opportunities for observation and support in classrooms and large-group settings such as the cafeteria, as well as informal dialogues with individual teachers or small groups. Pláticas served as an opportunity to address the challenge of integrating didactic professional development with ongoing reflection, problem solving, and skill-building across the year. Due to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020, the final professional development session and additional pláticas planned for the project were cancelled.

The target school for this program, Lewis Elementary*, served 325 students in grades prek-5 in a large metropolitan center in the Southwest. Sixty-five percent of students at Lewis were Hispanic, 13% were White, 9% were Black, 8% were Native American, 4% identified as two or more races, 1% identified as Asian and less than 1% identified as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. Lewis served a slightly higher number of students of color than the district as a whole which was 66% Hispanic, 20% White, 2.6% Black, 5.3% Native American, and 3% two or more races. However, the school’s student population experienced high rates of challenges relating to socioeconomic status relative to the district as a whole.100% of Lewis Elementary students were classified as receiving free or reduced-price lunch (compared to 70% in the district) and 27% of them were classified as chronically absent (17.6% in the district for other elementary schools). Lewis has the highest rate of student turnover in the district with more than 22% of students at Lewis changing schools during the school year. Given the social challenges facing the school, Lewis’ administration sought out the partnership with the researcher from a desire to integrate trauma-informed practices into their efforts to reform their school wide responses to challenging student behaviors. These efforts were part of a larger school reform effort at Lewis after it was identified as in need of intensive intervention and at-risk of closure.

Teacher demographics were not collected directly to protect staff anonymity because results were shared between the researcher and school administration. However, district data provides insight into the staff at Lewis Elementary. The school employed 25 teachers and 11 EAs over the course of the academic year (not all remained the entire year); 19 additional staff served in various administrative capacities although some served multiple schools including Lewis. Staff/teachers were 82.5% female and 17.5% male; they were 50.9% Hispanic, 45.6% White, 1.8% Black, and 1.8% Asian. Overall, staff demographics were very similar to that of the district overall.

2 Methods

This exploratory multiple-methods study sought to assess the impact of a holistic and comprehensive approach to teacher training and consultation around trauma-informed practices over the course of a school year.

2.1 Data sources

Data were collected through an anonymous online survey administered via Qualtrics to all Lewis teachers who participated in the year-long professional development program (N = 39). Teachers at Lewis completed the ARTIC-10 (10-item school version of the ARTIC) online in May 2019 prior to any engagement with trauma-informed professional development. The ARTIC is a validated scale assessing attitudes toward trauma-informed care which offers a version specifically designed for educators and school staff [3]. In addition to re-administering the ARTIC-10, the post-intervention version of the survey (administered in May 2020) included a series of Likert-scale and open-ended items designed to get additional teacher perspectives on the experience. These items assessed the degree to which teachers felt that the year-long professional development had a positive impact on the school, positively influenced teacher attitudes toward students, positively influenced teacher attitudes toward families and community, positively influenced teacher practices, and positively influenced school policies/practices.

Additional items allowed teachers to provide open-ended responses to the following questions: (1) What have you personally learned because of the professional development on trauma-informed practices this year? (2) What practices have you changed because of the professional development on trauma-informed practices this year? (3) What has changed in your school because of the professional development on trauma-informed practices this year? And (4) What are the biggest barriers to implementing these changes that you have experienced?

Given the collaborative nature of this project and the fact that results would be shared with school administration, the survey was anonymous and participant demographic or other potentially identifying information was not collected. Thirty-eight teachers participated in the initial survey and twenty-nine participated in 2020. One new teacher was hired after administration of the pre-survey and was not included in data reporting. After cleaning incomplete responses, post-intervention data collection included twenty-four responses. Importantly, the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 limited the scope of the project and likely impacted post-intervention data collection.

2.2 Data analysis

ARTIC scores were initially analyzed using descriptive statistics. An independent samples t-test was administered to assess whether there was a significant difference between the pre- and post-intervention scores on the ARTIC-10. Researcher-created Likert-scale items assessing teacher perceptions of the impact of the professional development were analyzed to identify the percentage of respondents who selected each value (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Subsequently mean scores for each item were calculated. Because open-ended responses were more limited and often brief in nature, these data sets were thematically summarized to describe general themes and present novel responses which reflected unique perspectives.

2.3 Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was approved by both the school district’s and the researcher’s Institutional Review Boards (IRB) prior to any data collection activities. All research activities were performed in accordance with standards for exempt review under the U.S. Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (the “Common Rule”). Information regarding potential risks and benefits of participation, participant rights, and other required elements of informed consent were included in the landing page for the online survey; those consenting to participate indicated so in their online response prior to answering any research questions. While all teachers who would be participating in the professional development activities were solicited to complete the survey, it was not mandatory, and they had the option to decline participation. Because the researcher held a dual role as both professional development/consultation provider and evaluator and given the fact that project data would be shared with school and district administration to inform future efforts, the survey was entirely anonymous with no demographic or potentially identifying information collected.

3 Results

3.1 ARTIC scores

Overall, mean total scores on the ARTIC-10 increased from 52.82 in 2019 (n = 38, SD = 7.45.) to 55.17 in 2020 (n = 24, SD = 7.8.) An independent samples t-test yielded a one-tailed p-value of 0.12 indicating no significant difference between the scores in the post-intervention and pre-intervention data sets. Table 1 depicts the mean and standard deviation for responses to each item on the ARTIC in 2019 (pre-intervention) and 2020 (post-intervention) as well as total ARTIC scores for participants. All items except item three (If students say or do disrespectful things to me, it makes me look like a fool in front of others: If students say or do disrespectful things to me, it doesn’t reflect badly on me), item eight (I realize that students may not be able to apologize to me after they act out: If students don’t apologize to me after they act out, I look like a fool in front of others.) and item nine (I feel able to do my best each day to help my students: I’m just not up to helping my students anymore.) demonstrated growth ranging from 0.13 to 0.64 on the seven-point scale.

3.2 Perceived impact of professional development

Survey items assessing teacher perspectives on the impact of the professional development effort over the year suggested that, in general, teachers agreed or strongly agreed that the program had has a positive impact on the areas assessed (mean scores of 4.2–4.3 on a 5-point scale). While scores were generally positive, standard deviation in responses was notably higher on items assessing changes to practice at the teacher or school level (versus those assessing attitudes or more general perceptions). Table 2 depicts the percentage of respondents who selected value on the 5-point Likert scale.

3.3 Open-ended responses

Approximately half of participants provided qualitative responses to open-ended items assessing their learning, changes in their practices, schoolwide changes, and barriers or challenges they had experienced. General themes from these responses are summarized below.

3.3.1 Personal learning

Four comments indicated that a key area of learning for them involved a new understanding of families and resulting increase in openness and empathy toward them; these respondents described their emerging understanding of the connections between student experiences outside of school and their behavior in school. One respondent described feeling more confident in their ability to recognize trauma. Four respondents referenced increased sensitivity toward their students and their understanding of the importance of self-reflection, and this being important to the student–teacher relationship. Two respondents mentioned the importance of checking or minimizing their own judgements or assumptions about students and families.

3.3.2 Changes in individual practices

The predominant response in this area was that they spent more time and effort on attending to student and family social and emotional needs and building relationships. One respondent mentioned including Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) lessons in their daily routine. Others stated that they were more caring, patient, and understanding of students or families; two addressed an increased focus on being a reliable adult for students and making a greater attempt to understand the student’s background. One respondent said they now utilized more mindfulness practices in the classroom, and another respondent said they ignore unwanted behaviors, avoid power struggles, and reach out for help to colleagues because of the training.

3.3.3 School wide changes

This question elicited a variety of responses that focused on student behavior, families and resources, and teacher responses. One respondent stated that students seem more informed regarding how to behave, and one noted a drop in “tier two” behaviors. One response said students seem to be less confrontational with both peers and staff. Another response noted a reduction in suspensions and expulsions. One participant indicated that there were “less consequences,” though it was not clear if this was interpreted positively or negatively. Responses that touched on families noted that now there are now more resources available, that there is more meaningful and respectful involvement of parents, and there are more students or families pursuing resources in the community. A respondent said they no longer feel alone, and that they felt that “everyone is in it together.” Another noted that they now were less likely to take things personally and respond with patience instead. One response noted that they did not think anything had changed.

3.3.4 Barriers/challenges

Three respondents noted time or strict academic demands (by the district and state) as barriers to implementing trauma-informed practices. Two noted a lack of strategies for working with students who have challenging behaviors. One listed a lack of basic resources for students and families being a barrier, such as access to education, housing, food, and childcare. Two referenced parents/families serving as a challenge or barrier- such as not having their children at school or being challenging or even suspicious. One respondent said the work in school is only half of the problem, and trauma-informed educational approaches do not address home life which continues to cause harm to some children. One respondent said staff “buy-in” serves as a barrier and another noted that “being on” all the time is overwhelming.

4 Discussion

This study sought to describe the impact of year-long, research-informed approach to teacher professional development in trauma-informed education. Direct changes in teacher attitudes toward trauma-informed care were measured by the ARTIC-10; teachers also provided quantitative and qualitative descriptions of their perceptions of the ways in which this professional development project had informed them, changed attitudes, changed personal practices, and changed schoolwide practices while also identifying barriers to change they had experienced.

While modest growth in attitudes toward trauma informed care were noted on the ARTIC overall and on seven out of ten items, findings suggest that even the comprehensive approach to training and professional development did not have a significant, durable impact on teacher attitudes toward trauma-informed care. Teachers in this study participated in a least 6 h of direct, interactive training and received ongoing support and dialogue around their practices for nearly one year. This training was also embedded in larger school reform activities to promote congruence between training/support and broader school policies and practices. Despite the depth of these efforts, growth in positive attitudes toward trauma-informed care was modest.

Responses to the set of researcher-created survey items assessing teacher perceptions of the impact of this project complement these conclusions. In general, respondents agreed that the professional development project had a positive impact on the areas assessed with over 80% of teachers agreeing or strongly agreeing that the project had a positive impact in all areas assessed. And yet, questions that assessed overall impact or changes to practice (as opposed to attitudes specifically) had lower rates of participants that strongly agreed and higher standard deviations, indicating a wider variation in participant perceptions.

Open-ended responses presented a range of ways in which teachers described the substantive impact of this project on their knowledge and personal practices while also highlighting limitations in the potential impact of this work. While teachers described new beliefs and approaches and positive changes in their school environments, they also described feeling overwhelmed at times and stifled by the ongoing reality of community trauma. Importantly, open-ended responses tended to reflect a feeling of being bounded by external factors (family needs, community trauma etc.) more often than a feeling of being bounded by issues of personal capacity or school implementation issues.

In understanding the documented effects/limitations of this project, it is important to note that teachers in this sample began the project with relatively high ARTIC scores (indicating existing positive attitudes toward trauma-informed care). With an initial mean score of 52.82 points out of a possible seventy, there is a strong possibility of a ceiling effect related to the impact of professional development on attitudes. This could explain why no substantial change on the ARTIC was observed despite largely positive responses to the impact of the project described in other portions of the survey. Beyond the implications of this observation for our data, it raises another important consideration that links the findings in this study to previous findings: the reality that practices, rather than attitudes, tend to be both more intransigent and more consequential for meaningful development in trauma-informed education.

This suggests that as we move forward in an era of increase trauma-awareness and responsiveness, efforts to provide trauma-informed professional development to teachers may be well-served by increasing their focus on providing clear strategies and supports to implement practice change rather than focusing exclusively on changing attitudes. While this project sought to address this issue through ongoing collaboration and office hours, it is possible that a stronger focus on specific practices and skills in the initial training would have benefited participants. Additionally, the generally positive attitudes toward trauma-informed care that existed in this school prior to any specific training in the area of trauma must be considered. More research is needed to determine if this finding is an outlier; if it is not, it will be important to reconsider the traditional focus on changing attitudes characteristic of professional development in this area.

It is true that educators must “recognize” and “realize” the impact of trauma to begin “responding” and “resisting retraumatization” (SAMHSA, 2014). And yet, this study and previous research [17], suggests that overemphasis on the first two elements (respond and recognize) limits the potential of trauma-informed work in schools. This can be viewed as an important positive shift resulting from the increased awareness of and focus on trauma-informed work in schools over the last two decades. It is worth considering, that, for many teachers, the foundation has been laid. Moving forward, focusing on how, rather than why, to shift toward trauma-informed practices is critical.

4.1 Limitations

This study represented an effort to document the outcomes of research-based, community-engaged planning and evaluation of trauma-informed professional development in one school. Given this design, findings are not generalizable to other settings. Additionally, researchers cannot definitively determine whether the limited growth in positive attitudes toward trauma-informed care observed was a result of a ceiling effect, weaknesses in the training format/quality, or general limitations in the impact of professional development on trauma-informed development.

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic and the ended in-person instruction with approximately 2.5 months remaining in the project. This limited the scope/duration of this project and final data collection. although the directionality of this impact on the data collected is difficult to ascertain. On one hand, in light of the pandemic the need to understand and respond to trauma was likely more evident than ever. And yet, as teachers were overwhelmed and largely out of contact with the students due to engagement challenges at Lewis, it is also possible that this stress could have depressed scores.

4.2 Conclusion and implications

While the professional development project in this study was described as having a positive impact on teachers and Lewis Elementary, this study also serves as a caution against some common assumptions about trauma-informed professional development. First, findings should cause us to question the assumption that effective professional development should focus primarily on changing teacher attitudes toward trauma-informed care, leaving implementation issues to be addressed later. While more research is needed, these preliminary data suggest that many teachers are positively oriented toward trauma-informed prior to their first training experiences. As a result, professional development providers could benefit from assessing attitudes and tailoring training accordingly. Where appropriate, focusing training more heavily on skill development and implementation issues could support increased impact.

Second, our findings echo other work that has cautioned against the assumption that providing professional development equates to the integration of trauma-informed perspectives or practices [15]. Our data in conjunction with existing models for trauma-informed schools [23] strongly supports the notion that professional development in this area is best viewed as only the beginning step in a process.

Considering the significant interest many schools/districts have in providing trauma-informed professional development for teachers and the increasing number of states requiring such training, ensuring that these opportunities have the intended effect and lead to meaningful changes is essential. For those seeking or providing professional development to build trauma-informed schools, we offer some critical considerations based in the literature and substantiated by our findings here.

Invest in data-driven, research-based professional development. Not all training is created equal. This study demonstrated that even rigorous, community-centered approaches to training may leave implementation gaps. Professional development providers and the schools/districts that invite them should consider assessing teacher knowledge and perspectives prior to training in order to use a school’s scarcest resource, time, well. Where this is not possible, ensuring that time spent focused on foundational knowledge around trauma and trauma-informed perspectives clearly translates into actionable steps for teachers is critical.

Connect professional development to ongoing school improvement efforts through continual integration and skill-building. The adoption of trauma-informed perspectives and practices is fundamentally an approach to organizational change [5]. School leaders are encouraged to consider how trauma-informed approaches can transform the organizational functioning of their school and to communicate expectations relating to the impact of training in a way that places the development of trauma-informed systems at the center of the work of the school. They are also encouraged to consider opportunities to integrate didactic professional development with opportunities for ongoing consultation to continually assess challenges and provide directed skill-building and problem-solving where appropriate. The current study sought to do this in a culturally relevant format through the implementation of pláticas throughout the year although this format may vary based on school culture and context-specific factors.

Consider implementer capacity. Informal data collected from pláticas in this study echoed existing research demonstrating that reform fatigue and the impact of secondary traumatic stress are substantial threats to educator capacity to receive, integrate, and implement trauma-informed perspectives and practices. While efforts to support educators and encourage self-care can be helpful, it is critical that policy makers and leaders also consider more foundational opportunities to support educator well-being and capacity. In many cases, this might require substantial efforts to streamline, simplify, and clarify common goals and expected practices. The adoption of trauma-informed perspectives and practices is a process that involves substantial commitment to personal reflection in educators. School leaders and policy makers are encouraged to address capacity issues that may limit the space necessary for this growth and reflection to maximize potential outcomes.

Respond to the post-pandemic reality of collective trauma in future professional development. This study occurred at the outset of the pandemic as such data does not specifically inform the post-pandemic reality. Importantly, the pandemic has provided a new understanding of and direct experience with trauma for most educators. Whether they experience personal trauma or moved through the collective stress and trauma of the period, their positionality has shifted. The same reality is true of students and families. Collectively, we are both more aware of and more impacted by trauma. Any future efforts to support schools in developing and sustaining trauma-informed approaches will need to directly grapple with the ways in which the period immediately following this study exposed individuals and entire communities to trauma and grapple with the long-term impact of that reality and the challenges and opportunities it presents. Research in this area will need to consider the differential impact the pandemic had on different communities inside and outside of schools and ensure consideration of these realities as they draw conclusions about the impact and efficacy of trauma-informed professional development and approaches.

This case study contributes to the existing literature documenting the impact of training around trauma-informed practice in schools by reinforcing some of what is already known and raising critical questions about the implicit association between providing training and changing practices that has characterized some of the current interest in trauma-informed work in schools. The capacity for professional development to increase positive attitudes toward and knowledge about trauma-informed practices is clear. However, the significance of this increase and its relationship to changes in practice should be questioned. As research into the impact of various approaches to training and support for educators continues to emerge, policy makers, school leaders, and educators are encouraged to view increasing positive attitudes toward trauma-informed care in teachers (and professional development intended to achieve this end) as but one step in the process of transformation for schools committed to trauma-informed practices.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable direct request.

References

Anderson EM, Blitz LV, Saastamoinen M. Exploring a school-university model for professional development with classroom staff: teaching trauma-informed approaches. Sch Commun J. 2015;25(2):113–34.

Avery, Morris H, Galvin E, Misso M, Savaglio M, Skouteris H. Systematic review of school-wide trauma-informed approaches. J Child Adoles Trauma. 2020;14(3):381–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-020-00321-1.

Baker CN, Brown SM, Wilcox PD, Overstreet S, Arora P. Development and psychometric evaluation of the attitudes related to trauma-informed care (ARTIC) scale. Sch Ment Heal. 2016;8(1):61–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9161-0.

Berger E. Multi-tiered approaches to trauma-informed care in schools: a systematic review. Sch Ment Heal. 2019;11(4):650–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09326-0.

Bloom SL. Creating sanctuary: toward the evolution of sane societies. England: Routledge; 2013.

Borko H. Professional development and teacher learning: mapping the terrain. Educ Res. 2004;33(8):3–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033008003.

Schepers C, Young KS. Mitigating secondary traumatic stress in preservice educators: a pilot study on the role of trauma-informed practice seminars. Psychol Sch. 2022;59(2):316–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22610.

Chafouleas SM, Johnson AH, Overstreet S, Santos NM. Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. Sch Ment Heal. 2016;8(1):144–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8.

Chafouleas S, Pickens I, Gherardi SA. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): translation into action in K12 education settings. Sch Ment Heal. 2021;13:213–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09427-9.

Cole SF, Eisner A, Gregory M, Ristuccia J. Creating and advocating for trauma-sensitive schools. Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative, partnership between the Massachusetts Advocates for Children and Harvard Law School. 2013.

Compassionate Schools (n.d.) Compassionate schools project. https://www.compassionschools.org/program/

Enhancing Trauma-Awareness (n.d.).https://www.thesanctuaryinstitute.org/services/training-consultation/enhancing-trauma-awareness/

Fierros CO, Bernal DD. Vamos a platicar: the contours of pláticas as Chicana/Latina feminist methodology. Chicana/Latina Stud. 2016;15(2):98–121.

Fleckman JM, Petrovic L, Simon K, Peele H, Baker CN, Overstreet S. Compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, and burnout: a mixed methods analysis in a sample of public-school educators working in marginalized communities. Sch Ment Heal. 2022;14:1–18.

Gherardi S. Improving trauma-informed education: Responding to student adversity with equity-centered, systemic support. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/trauma. 2022.

Gherardi SA, Garcia M, Stoner AL. Social justice and trauma-informed education: Gaps, barriers, and next steps. Int J School Soc Work. 2021. https://doi.org/10.4148/2161-4148.1070.

Gherardi SA, Flinn RE, Jaure VB. Trauma-sensitive schools and social justice: a critical analysis. Urban Review. 2020;52:482–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-020-00553-3.

Herman A, Whitaker R. Reconciling mixed messages from mixed methods: a randomized trial of a professional development course to increase trauma-informed care. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;101: 104349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104349.

Hydon S, Wong M, Langley AK, Stein BD, Kataoka SH. Preventing secondary traumatic stress in educators. Child Adolescent Psychiatry Clin N Am. 2015;24(2):319–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2014.11.003.

Lawson HA, Caringi JC, Gottfried R, Bride BE, Hydon SP. Educators’ secondary traumatic stress, children’s trauma, and the need for trauma literacy. Harvard Educ Rev. 2019;89(3):421–47. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-89.3.421.

Maynard BR, Farina A, Dell NA, Kelly MS. Effects of trauma-informed approaches in schools: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1018.

McIntyre EM, Baker CN, Overstreet S. Evaluating foundational professional development training for trauma-informed approaches in schools. Psychol Serv. 2019;16(1):95–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000312.

Missouri Model for Trauma-Informed Schools (n.d.). https://dmh.mo.gov/media/pdf/missouri-model-trauma-informed-schools

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (n.d.). Secondary traumatic stress. https://www.nctsn.org/trauma-informed-care/secondary-traumatic-stress

Overstreet S, Chafouleas SM. Trauma-informed schools: introduction to the special issue. Sch Ment Heal. 2016;8(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9184-1.

Parker J, Olson S, Bunde J. The impact of trauma-based training on educators. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2020;13(2):217–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-019-00261-5.

Petrone R, Stanton CR. From producing to reducing trauma: a call for “trauma-informed” research (ers) to interrogate how schools harm students. Educ Res. 2021;50(8):537–45.

Post PB, Graybush AL, Flowers C, Elmadani A. Impact of child–teacher relationship training on teacher attitudes and classroom behaviors. Int J Play Ther. 2020;29(3):119–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/pla0000118.

Rodger S, Bird R, Hibbert K, Johnson AM, Specht J, Wathen CN. Initial teacher education and trauma and violence informed care in the classroom: preliminary results from an online teacher education course. Psychol Sch. 2020;57(12):1798–814. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22373.

Sonsteng-Person M, Loomis AM. The role of trauma-informed training in helping Los Angeles teachers manage the effects of student exposure to violence and trauma. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2021;14(2):189–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021-00340-6.

Stipp B, Kilpatrick L. Trust-based relational intervention as a trauma-informed teaching approach. Int J Emot Educ. 2021;13(1):67–82.

Temkin D, Harper K, Stratford B, Sacks V, Rodriguez Y, Bartlett JD. Moving policy toward a whole school, whole community, whole child approach to support children who have experienced trauma. J Sch Health. 2020;90(12):940–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12957.

Thomas MS, Crosby S, Vanderhaar J. Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades: an interdisciplinary review of research. Rev Res Educ. 2019;43(1):422–52.

Venet AS. Equity-centered trauma-informed education. WW Norton. 2021.

Yohannan J, Carlson JS. A systematic review of school-based interventions and their outcomes for youth exposed to traumatic events. Psychol Sch. 2019;56(3):447–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22202.

Zakszeski BN, Ventresco NE, Jaffe AR. Promoting resilience through trauma-focused practices: a critical review of school-based implementation. Sch Ment Heal. 2017;9(4):310–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9228-1.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the teacher and school leadership who participated in this project for their willingness to engage in this work and explore the outcomes. We also acknowledge the community school partnership which made this work possible.

Funding

Albuquerque Bernalillo community Schools Partnership.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. Collaborated with host institutions to design the intervention and collect data. A.S. supported data analysis. Both authors collaborated on the manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gherardi, S.A., Stoner, A. Transcending attitudes: teacher responses to professional development in trauma-informed education. Discov Educ 3, 132 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00207-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-024-00207-6