Abstract

Purpose

There is growing concern over the readiness of orthopedic surgical residents and fellows for independent surgical practice upon completion of their training. This study aims to explore orthopedic surgery (OS) trainees’ experience of accessing operative autonomy by eliciting their perceptions and techniques implemented to gain autonomy.

Methods

OS residents and fellows were invited to participate in focus group interviews via a convenience sampling approach. A non-faculty facilitator led the discussions using an interview guide to prompt conversation. All interviews were recorded, de-identified, and then transcribed. Three investigators iteratively analyzed transcripts to identify emerging themes until thematic saturation was achieved. All interviews were performed at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, an academic medical institution, in Columbus, Ohio.

Results

A total of 16 residents and 2 fellows participated. Two themes emerged: (1) optimal setting: trainees were allowed more operative autonomy in trauma and on-call cases than elective cases, though they perceived it was their responsibility to earn autonomy; (2) techniques: two techniques promote trainees’ access to autonomy, including trainee-initiated techniques (i.e., building relationship, preoperative planning, knowing attending preferences, and effective communication); and (3) faculty-initiated techniques (i.e., setting expectations, indications conference, and providing graduated autonomy).

Conclusions

Our study findings suggest OS trainees tend to access least autonomy in elective OS cases. Although trainees perceived earning autonomy as their responsibility, faculty and resident development is recommended to enhance teaching and learning techniques to increase trainees’ practice readiness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2017, orthopedic surgery (OS) senior residents at the American Orthopaedic Association Resident Leadership Forum expressed growing concern that they receive inadequate operating room (OR) autonomy, leaving them unprepared for independent practice. Autonomy may be defined by the four-level Zwisch Scale, a validated framework that defines four progressive stages of autonomy and associated resident behaviors [1, 2].While the names of each stage have been revised since the original model, the definitions of each stage remains the same. Show and tell, the lowest level of autonomy, limits resident behaviors to observing and holding surgical tools while the attending dictates every maneuver. Residents then progress to Active Help when they begin to actively anticipate surgeons’ needs and demonstrate an ability to perform different parts of the operation with assistance. Passive Help, the third stage, involves setting up and accomplishing the next steps of the surgical case with increasing efficiency and recognizing critical transition points. Supervision Only, the highest level of autonomy, includes independent practice without attending oversight, recovering from surgical errors, and recognizing one’s own limitations.

Duty hour restrictions, reimbursement policies, public misconceptions regarding resident training, medical liability concerns, inconsistent preparedness among trainees, and faculty-to-resident ratios have contributed to decreased surgical trainee autonomy [3]. Further, COVID-19 has introduced unforeseen challenges to post-graduate surgical training and the ongoing pandemic’s full impact remains largely unknown [4].

Much of the burden for gaining and accessing operative autonomy falls on trainees, though the attending surgeon is the ultimate decision-maker in the OR. Woelfel et al. found that residents in General Surgery and Obstetrics and Gynecology use a three-stage method for achieving opportunities for autonomy consisting of building rapport, developing entrustment, and finally gaining autonomy [5]. Additionally, faculty state they are more inclined to provide greater autonomy to residents who demonstrate preparation for the case, who are at the appropriate post-graduate year (PGY) of training for the case’s level of complexity, and have a good reputation for their clinical skills outside of the OR [6]. The criteria for granting resident OR autonomy are therefore largely subjective. Without an objective way to assess how ready a trainee is for autonomous opportunities, attending biases could influence who receives the best training opportunities (page 2).

Within orthopedics resident and fellow training, little is known about the process by which residents gain access to autonomy in the OR. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore OS trainees’ experience of accessing autonomy in the OR by eliciting their perceptions and techniques implemented to gain autonomy. Ultimately, these findings will contribute to faculty and resident development in aid of trainees’ accessibility of operative autonomy to optimize their readiness for practice.

Materials and methods

Setting and participants

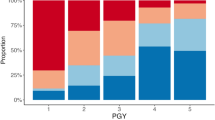

After approval by the institutional review board, focus group interviews were conducted with residents and fellows from the Department of Orthopaedics at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. The residency program is composed of six PGY1s, six PGY2s, six PGY3s, six PGY4s, seven PGY5s, and seven fellows. Focus group interviews were facilitated based on PGY levels. This structure allowed participants to share their experiences with peers in a comfortable environment. Compared to an interview, focus groups lend themselves to a collaborative sharing of experience. This helped the trainees discuss themes among themselves and generate ideas and examples they may not have thought of on their own. This study received IRB approval from Ohio State University.

Data collection and analysis

Between June and July 2021, six virtual focus group interviews were conducted and each lasted 60 min. A non-faculty facilitator conducted each interview to facilitate an authentic discussion on autonomy. The interviews were semi-structured using a scripted interview guide based on literature review and previous work by the authors to help facilitate the discussion [5, 7]. All subjects consented to have the interview audiotaped. Interview recordings were transcribed.

Three investigators, composed of two orthopedic attendings (RD, DF) and one medical student (JH), independently reviewed and coded the interview transcripts to identify emerging themes through a hybrid deductive–inductive thematic analysis. Some themes were mentioned word for word in the interviews. In these cases, these themes were explored in further depth during the interview. Other themes were deduced through examples given by trainees that centered around a common idea. In this study, analysis was focused on two key interview questions: “How do fellows and residents perceive their autonomy in the OR?” and “What techniques do trainees perceive to be helpful in gaining access to autonomy in an OR setting?” Investigators discussed coding disagreements until reaching a consensus. This process continued until the thematic saturation was achieved.

Results

A total of 18 orthopedic trainees, including 11 junior residents (PGY 1–3), 5 senior residents (PGY 4–5), and 2 fellows (PGY 6), participated in six focus group interviews. Two themes emerged: 1) optimal setting which was regarding trainee experience of accessing autonomy in different operative settings (Tables 1 and 2) techniques for gaining enhanced access to operative autonomy. Techniques for gaining operative autonomy were divided into actions that trainees themselves may initiate (Table 2) and techniques that faculty may initiate to help residents access more autonomy (Table 3).

Optimal setting for accessing autonomy

Residents noted that they experienced differing levels of autonomy depending on the surgical case setting, such as when on-call versus elective surgical procedures (Table 1). In every interview our team conducted, all residents agreed that they would likely have the greatest access to autonomy in trauma surgical cases. Although we did not quantify autonomy by setting, the commonality of experience and harmonious agreement among trainees bolsters their claim’s validity. A junior resident stated they had “experienced full autonomy only in a trauma case” (G2R3). Another resident stated, “the only time you get full autonomy is on trauma versus in attendings’ subspecialties where they are naturally more hands-on” (G2R1) Senior residents agreed and elaborated that this is due to the cases being more variable. Furthermore, the preoperative plan is often made with the residents as they discuss the injury pattern and develop a surgical plan on the day of surgery.

Conversely, both junior and senior residents feel they receive the least autonomy during elective surgery cases. Elective cases tend to be more personal to attending surgeons, who often have built a relationship with each patient. For example, one junior resident mentioned reputations are an important aspect of a doctor’s career. Thus, “if an attending has an elective case for a patient with whom they have a relationship and have their stake and reputation on the line, they are less likely to hand over the reins and let the resident operate” (G4R2).

Techniques for gaining access to operative autonomy

Two types of techniques for gaining operative autonomy emerged from focus group interviews. They were (1) trainee-initiated techniques (i.e., building relationships, preoperative planning, knowing attending preferences, and effective communication) and (2) faculty-initiated techniques (i.e., setting expectations, indications conference, and providing graduated autonomy).

Trainee-initiated techniques

Building relationship

Trainees noted they needed to build relationships with an attending surgeon before they could expect substantial OR autonomy. Methods of building this relationship varied between junior and senior residents. Junior residents mostly relied on “sharing common interests” and having “conversations about things outside of surgery” (G1R1). The goal of this strategy is to get to know the attending surgeon on a more personal level. “Being friendly” and “building trust and relationships outside of the OR go a long way” (G1R1). Senior residents focused on demonstrating competence outside of the OR. They identified recognition from attendings for “being thorough in the clinical setting” and completing “whatever task you are assigned,” as keys to building a strong relationship with attendings (G5R2).

Preoperative planning

Both junior and senior residents reported having a strong preoperative plan is essential to building entrustment from attending surgeons. A junior resident stated these plans can demonstrate to attendings “you know what you are doing before walking into the OR” (G2R3) When the attending knows the resident has the proper knowledge base for the procedure, then the resident just needs to”execute it physically. That will show attending surgeons they can trust them” (G2R3). In addition to having a preoperative plan, junior residents found reviewing it with their attending surgeon helped them ensure their plans aligned. They felt this made attendings more comfortable allowing them autonomy.

Senior residents noted that having a thorough preoperative plan is the best way to build autonomy. The senior residents wanted to show attending surgeons they know the patient’s imaging, laboratory work, clinical and social history, and that they have a surgical plan. The preoperative plan is often written on a single sheet of paper that the fellow or resident posts in the OR. It contains information on the approach, instruments needed, how to drape and position the patient, and any other important items needed for the procedure. Since attending surgeons may be hesitant to hand over the reins to a resident or fellow, having a thorough plan demonstrates preparation and can be crucial to gaining entrustment.

Attending preferences

Trainees found that understanding and adopting attending surgeon preferences helped them improve their operative autonomy and build rapport. Many of the residents and fellows took note of attending surgeon preferences for every procedure. Specifically, they focused on set up and positioning, tourniquet use, type of draping, graft choice, and implant preference, among other decisions that often occur in a stepwise manner for each surgery. For example, if a trainee can take the initiative to set up and position a patient in the same way their attending surgeon would, then that attending may be more compelled to trust them and consequently grant them a higher degree of operative autonomy for the procedure.

Both junior and senior residents found knowing attending surgeon preferences beneficial. A junior resident noted “attendings are more willing to give autonomy to residents who do the procedure the way they like” (G2R1). Junior residents added it “is helpful to talk through the case with the senior resident to learn what to do and what a particular attending will expect” (G1R2). Then, by incorporating these attending preferences into the preoperative plan, residents felt they had a better chance of having some level of autonomy in the OR.

According to residents, being a strong assistant surgeon can also improve surgical autonomy. Junior residents noted working hard as an assistant surgeon can help to regain autonomy when they have lost the attending surgeon’s trust during a procedure: “when you lose autonomy in a case, do not just step away. Be a good assistant because a good surgeon is a good assistant. The attending may recognize your effort and hand the instrument back to you” (G2R1). A common theme emerged during the interviews: when an attending perceives a resident to be exceptionally well prepared or giving excellent effort, they may feel more comfortable providing increased autonomy.

Effective communication

For junior residents, we found effective communication may be broken up into two categories. The first is demonstrating preparation and critical thinking regarding the case; the second is knowing one’s own limitations. The former was usually done through asking engaging questions and verbalizing one’s actions and thoughts while operating. Multiple residents noted they try to have “at least one good question about the case,” which they usually pose to the attending surgeon after the procedure (G2R3). Questions can be “what if” questions, differences in techniques between attending surgeons, or asking about aspects of the case with which the surgical team struggled.

Residents noted that acknowledging their limitations to the attending surgeon often improved their autonomy. “Attendings will be more likely to trust you when they know that you will be willing to ask for their help or stop when you do not feel comfortable,” said a junior resident (G2R2). Senior residents also expressed the importance of knowing their limitations, especially when they have a strong relationship with the attending. Acknowledging their limitations in these settings allows them to ask for more opportunities to practice the skills in which they lack proficiency.

Faculty-initiated techniques

In addition to common themes for gaining operative autonomy, the residents and fellows described methods attending surgeons—whom they perceived as effective teachers—have used to provide autonomy. Residents identified that attending surgeons successfully promoted trainee autonomy by setting clear expectations, using indications conferences, providing graduated autonomy, and allowing opportunities for residents to productively struggle during surgeries.

Setting expectations

Trainees found they were more likely to successfully and safely gain autonomy when attending surgeons explicitly and clearly stated their expectations for trainees. Residents and fellows feel that knowing the attending’s expectations helps them act in accordance with their attending’s preferences and build autonomy.

Indications conference

Indications conferences are meetings between trainee(s) and attending(s) for the review of upcoming cases. Both junior and senior residents found these meetings helpful for providing an extra level of preparation before a procedure. Junior residents preferred reviewing cases with senior residents, whom they described as generally more “available” than attending surgeons (G3R3). Conversely, senior residents and fellows have more access to attending surgeons, so they can generally meet with each other more readily. Trainees noted that indications conferences are particularly helpful for complex cases. A senior resident noted about a week before these challenging or rare cases, they “discuss the case and look up literature and techniques,” with the attending surgeon. They remarked that an indications conference “is a learning experience for everyone” (G5R3). Senior residents expressed their participation demonstrates investment in patient outcomes as well as improving as a surgeon. Residents elaborated that attendings feel this display of commitment which helps build entrustment.

Graduated autonomy

Trainees found they were able to keep patients safe and build their skills when attending surgeons provided them with graduated autonomy. Junior residents see graduated autonomy as vital to learning the nuances of operating. Residents felt that attending surgeons expect them to learn passively as they watch the operation. A Junior resident commented that they “can see something hundreds of times, but until they do it a few times, it is really hard to appreciate what is happening” (G1R4). They also noted “exponential growth and learning” from watching procedures only occurs after a resident “does the procedure a few times and gets the basics down” (G1R4). Otherwise, trainees often feel appreciating nuance is difficult as they may not know what to look for. Consequently, 10 out of the 11 junior residents tended to prefer more straightforward cases, such as tibial nails or simple knee arthroscopies, because they feel they receive more autonomy in these cases early in their training. Residents stated they learn the most when they have the opportunity to complete at least some of the procedure independently. Thus, trainees found that they have higher quality learning opportunities when attending surgeons progressively grant increasing amounts of autonomy, even if that initially means merely allowing the trainee to use the scalpel under their complete guidance.

According to junior and senior residents alike, providing opportunities for the resident to productively struggle also promotes learning and autonomy. This means allowing residents to work through difficulties on their own during surgery, or explorative learning. A senior resident noted, “the best learning opportunities come when attendings allow them to struggle through a procedure” (G4R1). A junior resident added “good attendings step back and let residents struggle. The more hands-on attendings are quicker to step in at any mistake or deviation from their preferred technique” (G2R2). Their advice to attending surgeons: “give [residents] time to think things through and refrain from intervening” (G5R1). The more opportunities residents have to learn operating strategies for themselves, the better prepared they feel for independent practice.

Discussion

In this study, we have identified orthopedic trainees’ perceptions regarding access to OR autonomy and techniques promoting access to increased autonomy at a single institution. As a PGY1, operative autonomy is rare. Most residents note having had their first fully autonomous experiences during their PGY2 year on their trauma rotation or on call. This aligns with current data which suggests residents’ surgical skills, as measured with the Ottawa Surgical Competency Operating Room Evaluation, improve the most as they progress from interns to PGY2. This jump in skill is even larger than the improvement from PGY2 year to PGY5 [8]. Thus, the extent and knowledge that residents gain during this time may allow attending surgeons to feel more comfortable granting autonomy to PGY2s than PGY1s.

As residents progress through their training and continue to build relationships with various attendings, they can ask for more autonomy with less risk of damaging relationships and are thus afforded more strategies for gaining autonomy. Competency, entrustment, and autonomy work in a positive feedback cycle (Fig. 1).

Residents demonstrate competency, which helps them gain entrustment from attending surgeons, who then let them build surgical skills through graduated autonomy, which is necessary for improving skills and demonstrating competency. Thus, the cycle repeats. It is important to mention that building strong relationships with attendings may be more difficult for those that are less extroverted and more prone to be affected by implicit bias. This could also be problematic because trainees who share similar backgrounds to their attendings may have an advantage in this area, and those who do not may have more difficulty gaining access to autonomous training.

Our findings suggest opportunities for surgical autonomy are not systematically built into curricula at this institution. Additionally, it has been shown that attending orthopedic surgeons tend to overestimate the amount of autonomy they provide their trainees [9]. Thus, incorporating more programs for building resident OR autonomy into OS training could improve the quality of education. In fact, previous studies have demonstrated that when intentional opportunities for autonomy are built into the curriculum, residents can improve their skills while keeping patients safe. For example, implementation of a post-call review conference during overnight trauma call proved to decrease resident decision-making and technical error rates while also maintaining patient safety [10]. Other initiatives in resident programs that have been shown to increase opportunities for autonomy include implementing a resident run minor surgery clinic, implementing a program that grants chief residents structured autonomy, and implementing cadaver-based simulation clinical skill sessions [11,12,13].

Our study also indicates that residents desire more opportunities for autonomy during elective surgeries. Lack of experience with elective procedures could be a contributing factor to why 90% of OS residents pursue fellowship after residency [14]. Moreover, an analysis of intraoperative resident involvement in 30,628 OS patients demonstrated resident involvement is associated with lower overall complications, medical complications, and mortality [15]. Therefore, providing residents opportunities for graduated autonomy has not been associated with worse outcomes.

Several limitations exist for this study. First, our findings are the result of a qualitative study based on self-reporting in focus group interviews. As a result, cognitive bias are unavoidable. However, our findings are able to provide new insights into OS trainees’ access to operative autonomy and contribute to the surgical education literature. This is especially valuable considering literature regarding autonomy largely focuses on general surgery. Secondly, this study was also conducted at a single institution, resulting in a limited sample size. Furthermore, the majority of participants were junior trainees, which may have skewed some of the themes identified. Perceptions on autonomy and the strategies to achieving that autonomy may change as trainees progress through their residency. Given the decreased number of senior residents, these perceptions may not have been captured. The demanding schedule of orthopedic surgery trainees was likely responsible why only 18 of 32 trainees participated in our study. We chose our interview dates and times based on when the most trainees were available and this was the resultant turnout.

Future studies should focus on investigating orthopedic surgery attendings’ perspective on the themes we identified in this study. Surgical attending’s perspective will further elucidate how autonomy can be granted safely as well as provide a framework for how orthopedic trainees may gain entrustment.

In conclusion, our study findings suggest OS trainees tend to access least autonomy in elective OS cases, though trainees perceived earning autonomy was their responsibility. Likewise, two main techniques that promote trainees’ access to operative autonomy are identified. To continue improving OS education, faculty and resident development is recommended to enhance teaching and learning techniques to increase trainees’ practice readiness.

Data availability

There is no associated data available for this study.

References

DaRosa DA, Zwischenberger JB, Meyerson SL, et al. A theory-based model for teaching and assessing residents in the operating room. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(1):24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2012.07.007.

George BC, Teitelbaum EN, Meyerson SL, et al. Reliability, validity, and feasibility of the Zwisch scale for the assessment of Intraoperative performance. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):e90–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.06.018.

Dougherty PJ, Cannada LK, Murray P, Osborn PM. Progressive autonomy in the era of increased supervision: AOA critical issues. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2018;100(18):e122. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.17.01515.

Stambough JB, Curtin BM, Gililland JM, et al. The past, present, and future of orthopedic education: lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(7):S60–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.032.

Woelfel I, Smith BQ, Strosberg D, et al. Residents’ method for gaining operative autonomy. Am J Surg. 2020;220(4):893–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.03.022.

Mattar SG, Alseidi AA, Jones DB, et al. General surgery residency inadequately prepares trainees for fellowship: results of a survey of fellowship program directors. Ann Surg. 2013;258(3):440–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a191ca.

Chen XP, Sullivan AM, Alseidi A, Kwakye G, Smink DS. Assessing residents’ readiness for or autonomy: a qualitative descriptive study of expert surgical teachers’ best practices. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.06.034.

Osborn PM, Dowd TC, Schmitz MR, Lybeck DO. Establishing an orthopedic program-specific, comprehensive competency-based education program. J Surg Res. 2021;259:399–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2020.09.016.

Foster MJ, O’Hara NN, Weir TB, et al. Difference in resident versus attending perspective of competency and autonomy during arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs. JB JS Open Access. 2021;6(1):e20.00014. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00014.

Yang BW, Waters PM. Implementation of an orthopedic trauma program to safely promote resident autonomy. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(2):207–13. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-00277.1.

Wojcik BM, Fong ZV, Patel MS, et al. The resident-run minor surgery clinic: a pilot study to safely increase operative autonomy. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(6):e142–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.08.016.

Wojcik BM, Fong ZV, Patel MS, et al. Structured operative autonomy: an institutional approach to enhancing surgical resident education without impacting patient outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225(6):713-724.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.08.015.

Kim SC, Fisher JG, Delman KA, Hinman JM, Srinivasan JK. Cadaver-based simulation increases resident confidence, initial exposure to fundamental techniques, and may augment operative autonomy. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(6):e33–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.06.014.

Daniels AH, DiGiovanni CW. Is subspecialty fellowship training emerging as a necessary component of contemporary orthopaedic surgery education? J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(2):218–21. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00120.1.

Edelstein AI, Lovecchio FC, Saha S, Hsu WK, Kim JYS. Impact of resident involvement on orthopaedic surgery outcomes: an analysis of 30,628 patients from the American college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program database. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2014;96(15):e131. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.M.00660.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Department of Orthopaedics, including the orthopedic trainess and faculty, for making this study possible. Specifically, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Duerr, Dr. Flanigan, and Dr. Chen for providing critical guidance and support, as well as the rest of the Orthopaedic Surgery and Sports Medicine faculty. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Mr. Hollman completed the study design, executed the group interviews, and transcribed the interviews. Mr. Hollman drafted the manuscript and along with Dr. Duerr. Mr Hollman, Dr. Duerr, and Dr. Flanigan analyzed the transcriptions for appropriate themes. Ms. Coffey-Noriega and Dr. Chen revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethical approval

This study utilized interview procedures. The Ohio State University IRB board has confirmed that this study remains exempt from ethical approval.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of their statements in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Appendix A

Appendix A

Focus group interview questions | Purpose |

|---|---|

First, I’d like to introduce the overall goal of this discussion: To help future residents and fellows gain more autonomy by demonstrating increased preparation and entrustability in the OR. We are interested in knowing your preferred techniques, decision-making, and self-improvement experience | The purpose of this section is to specify the goal of the discussion |

Notes: | |

When you hear the words “autonomy” and “entrustment” what comes to mind? Prompting questions: Q1: How do you define them? Q2: How do you show that you trust a resident or fellow? - Can you give specific examples? Does this vary by situation? How? Q3: Which case(s) do you feel a resident should be able to do completely on their own upon graduating? Is this because of the ease of the procedure, the frequency it is performed, or some other reason(s)? Is this a product of a residents having more chances to practice this procedure independently? | The purpose of this section is to start defining “autonomy” and “entrustment” to ensure our discussions are on the same page |

Notes: | |

[Trainee name] Can you tell me, what was your favorite case you did with a resident this week? What about this case did you like? What was the resident’s level of involvement/autonomy? Follow-up if high autonomy—why did you allow the resident to perform the procedure rather autonomously? Were they well prepared? Did they make a plan in advance? Prompting questions: Q4: What is your preferred technique? Q5: Does your preferred technique differ from that of other attendings? Q6: Why do you choose to perform this procedure that way? Any other comments? | The purpose of this section is to prompt their experience in preferred techniques and decision-making |

Notes: | |

Tell me about some challenges you have had with decision-making, such as deciding when to operate on patients? When not to? What to do in the OR? etc Prompting questions: Q7: Can you give me some examples? | The purpose of this section is to extract examples |

Notes: | |

We all need to do M&M Prompting questions: Q8: Is there anything that you learned that specifically has changed your practice? Q9: When you see a resident present at M&M, does this ever change how you will operate with this resident in the future? Can it have a positive or negative impact on the autonomy you are willing to give them or how much you trust them? | The purpose of this section is examining the effect of M&M and complications on trainee’s development |

Notes: | |

Let us discuss how you have seen residents gain autonomy in your time as an attending Q10: How have residents successfully gained your trust and consequently increased autonomy in the OR? Prompting questions: - What steps can they take before a procedure to gain entrustment? During? After? - If they answer with mastery of a particular skill: How do you find opportunities for residents to demonstrate mastery? - Do your strategies vary for different residents? | The purpose of this section is to gather information on trainee’s perspective for building autonomy |

Notes: | |

Lastly, is there anything that could help future chief residents learn better, but we currently lack or we are not aware of at the beginning of the chief year? Prompting question: Q11: Can you give some advice that helps our upcoming [chiefs/whatever PGY-level currently at] learn better or get more autonomy in the OR? | The purpose of this section is building on future improvement |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hollman, J., Coffey-Noriega, E., Chen, X. et al. Accessibility of operative autonomy from orthopedic surgery resident and fellow perspectives. Global Surg Educ 2, 72 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-023-00150-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-023-00150-4