Abstract

To assess the validity of intervention programs, we need to understand how they work and for whom. We evaluated a program for caregivers, ComTato, using a quasi-experimental design (pretest, posttest), to determine (a) which specific program-related gains are associated with improvements in well-being and (b) whether participants’ initial repertoire influences program benefits. All 37 participants (average age of 52.7 years) cared for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease. Participants completed instruments to evaluate their caregiving repertoire and their socioemotional well-being (use of constructive coping strategies, perceptions of burden, and quality of the caregiver-care recipient relationship). Caregivers learned about dementia, stress management, principles of social skills, the use of specific social skills, and principles of cognitive stimulation. We observed that (a) the greater the increase in knowledge and skills, the greater the increase in caregivers’ use of constructive coping strategies (r = .30, p = .037), with use of social skills being the component with the strongest association (r = .36, p = .014); (b) the greater the improvements in knowledge about social skills, the larger the reductions in conflicts with the care recipient (rho = − .28, p = .048); and (c) seven correlations indicated that the lower the caregivers’ initial repertoire, the greater their socioemotional health gains. Thus, increases in caregivers’ knowledge and socioemotional skills seem to contribute to improvements in their socioemotional well-being, and the lower their pre-existing repertoire, the more they benefitted from the program. In future studies, researchers should investigate how other socioemotional factors influence program benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The emphasis on evidence-based practice has led to many important studies on the effectiveness of theory-based, psychoeducational intervention programs. Changes in outcome variables are tested by examining effect sizes, but information about the process of change that is behind how a program works and for whom the program works also need to be clarified. That is, although specific components of program content and therapeutic strategies are often described, the effects of each component should also be verified. In this paper, we examined the relationship between how much participants learned in each module of an intervention program and how much their socioemotional well-being improved. Furthermore, it is important to analyze how pre-existing differences among participants influence the effects of a program. For some, a program may be too easy, when they already have the knowledge and skills the program offers, leading to a ceiling effect (no new learning). For others, a program may be too advanced, involving information they cannot assimilate or skills they cannot master, leading to a floor effect (unable to learn). Thus, we also examined the influence of participants’ initial repertoire on how much they learned during the program and how much they benefitted from the program. Based on this study, new information is gained about (a) the relationships among each component of the intervention process and intervention outcomes, providing evidence about program-related improvements in caregivers’ socioemotional skills and knowledge that seem to contribute to their well-being, and (b) information about the relationship between participants’ initial repertoire and how much they learned and benefitted, raising the issue of how to prepare programs that are useful to individuals with a range of pre-existing knowledge and skills.

Background

Challenges Faced by Those Who Care for an Elderly Family Member

The increase in average life expectancy has made interacting and living with elderly people a more normative part of life. However, those who assist dependent, elderly family members for a prolonged time encounter difficulties that often lead to a decline in their physical and socioemotional health (Amador-Marín and Guerra-Martin, 2017; Kwon, Ahn, Kim, and Park, 2017; Tomomitsu et al., 2014). Many caregivers experience reduced quality of life, significant stress, depression, anxiety, social isolation, and fatigue. They also experience exhaustion, on the one hand, and guilt on the other, for they often believe that they are not doing enough for their elderly relative. There may also be a negative impact on the caregiver’s interpersonal relationships (Pinto, Barham and Del Prette, 2016; Van der Lee, Bakker, Duivenvoorden and Droes, 2014). These problems tend to be most acute among those who care for a dependent relative with dementia, as these illnesses can lead to increases in communication problems, difficulties in remembering important information or in performing tasks based on reasoning, and aggressiveness (Pinto and Barham 2014; Wong and Zelman 2019).

Considering these problems, Queluz et al. (2019a) conducted a scoping review to identify which needs are most common among people who care for an older person with dementia. One of the most frequently reported needs was for educational programs that could help caregivers develop better ways of dealing with the care recipient’s illness. De Cola, Lo Buono, Mento, Foti, Marino, Bramanti et al. (2017) also investigated caregivers’ perceptions about their needs in relation to this role and found that 60% of them wanted information about how to deal with their family member’s illness.

In addition to helping caregivers learn more about how to manage their elderly family member’s needs that are related to basic activities of daily living, Queluz, Barham, Santis, Ximenes and Santos (2018) highlighted the importance of helping caregivers use their socioemotional skills in this complex and stressful context. This could help them maintain a higher quality relationship with the dependent elderly person and with other family members, over the course of the illness, as stressful situations tend to weaken relationships.

A poor-quality relationship can create a situation in which the elderly person is more vulnerable to negligence, abandonment, and violence, and the caregiver is likely to feel even more burdened (Barham, Pinto, Andrade, Lorenzini and Ferreira, 2015; Pinto et al. 2016; Queluz et al. 2018). On the other hand, when the relationship established between the caregiver and the older person is positive, with affectionate interpersonal interactions, caregivers tend to present fewer symptoms of depression, greater life satisfaction, and greater ease in adapting to their role (Alvira et al., 2015; Ferreira, Queluz, Ximenes, Isaac and Barham, 2017; Wong and Zelman 2019).

These findings point to the importance of using intervention strategies to strengthen the relationship between caregivers and the older person they care for (Gilhooly, Gilhooly, Sullivan, McIntyre, Wilson, Harding et al. 2016; Kwon et al. 2017; Zarit 2017), in addition to interventions that focus on practical ways of responding to changes in the elderly person’s cognitive and physical abilities. Thus, it is important to identify psychological repertoires that can help people adjust to their role as a caregiver, as well as identifying effective ways of teaching these skills to caregivers.

Skills That Help Caregivers Adapt

Having the abilities needed to use constructive coping strategies is important when dealing with stressful situations, including skills such as problem-solving, emotional regulation, and deriving meaning from responding to difficulties (Gilhooly et al. 2016). In addition to these abilities, some of the psychological and social resources that can lessen the negative effects of stress on a person’s satisfaction with life include self-esteem, optimism, seeking emotional support, and social contact (Ambriz, Izal and Montorio, 2012).

According to Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner (2009), based on the motivational coping theory (MCT), coping is a regulatory action that involves organized patterns of behavior, emotion, attention, and motivation. Coping is triggered when an experience is perceived as a threat or challenge to one or more basic psychological needs, including (a) relationship needs, fulfilled through close relationships with other people and feeling securely connected to others; (b) need for competence, based on being effective in interactions with the environment, achieving positive results and avoiding negative ones; and (c) need for autonomy, which involves the ability to choose one’s course of action.

Not surprisingly, the ability to use constructive coping strategies to adapt to new demands is one of the strongest predictors of mental and socioemotional health for people of all ages (Gilhooly et al. 2016; Monteiro, Santos, Kimura, Baptista and Dourado, 2018). For those caring for an elderly relative with health problems, being able to cope positively with the many problems that arise and being able to count on other people to play a supportive role are essential to maintaining their overall well-being (Ximenes 2018). However, Simonetti and Ferreira (2008) reported that caregivers mostly use coping strategies centered on emotional self-regulation, trying to accept situations that they are unable to modify, with few examples of efforts to solve problems.

As the number of studies on the results of intervention programs for caregivers has increased, it has become possible to determine characteristics of the programs that lead to the most positive outcomes. Both Kwon et al. (2017) and Kishita, Hammond, Dietrich, and Mioshi (2018) conducted systematic reviews to identify interventions that improve the well-being of caregivers who assist elderly people with dementia, considering outcomes such as depression, anxiety, burden, and quality of life. Kishita et al. reported that caregivers who participated in psychoeducational, skill-building interventions achieved the greatest reductions in burden. In addition, both groups of researchers found strong empirical evidence indicating that interventions based on cognitive behavior therapy models were effective for treating burden, anxiety, and depression.

Considering the evidence, both Zarit (2017) and Kwon et al. (2017) have suggested that programs based on the principles of cognitive behavior therapy can help caregivers improve their skills for coping with the challenges of dementia, reducing their feelings of burden and stress. Kwon et al. (2017) consider that mental health outcomes are improved by modifying dysfunctional thoughts about caregiving and by increasing the number of enjoyable activities that the caregiver and the care recipient do together. However, although the overall effects of many programs have been reported, researchers still need to (a) unpack information about the program components that lead to socioemotional health benefits (mechanisms of change), (b) verify whether the programs are more helpful for those with a particular entry-level skill set, and (c) test whether a focus on relationship skills is important, as distinct from efforts to work on other coping skills.

The ComTato Program

With the overall objective of improving the quality of the caregiver’s relationship with his or her relative and reducing perceptions of burden among caregivers who assist older people with dementia, Ferreira and Barham (2016) developed an intervention program called ComTato.Footnote 1 More specifically, ComTato is offered to caregivers individually, is based on the concepts of cognitive behavior therapy, and addresses both practical and socioemotional tasks that caregivers need to manage. The program is designed to (a) teach information about Alzheimer’s disease, so the caregivers can think about how to adjust to ongoing changes in their family member’s behavior; (b) help caregivers use more constructive coping and social skills, so they can make these adjustments in ways that help maintain or improve their relationships; and (c) use cognitive stimulation strategies, to interact with their family member with AD in positive ways, especially when the person with AD is behaving in a way that the caregiver finds upsetting or challenging to deal with.

The ComTato program was first tested in a small-scale study, using an experimental design (Ferreira 2014). After participating in the program, caregivers in the intervention group reported lower perceptions of burden and greater knowledge regarding dementia, coping strategies, and social skills, compared to caregivers in the control group (Ferreira and Barham 2016; Campos et al., 2019), and these results have been replicated (Ferreira 2015; Ferreira et al. 2017; Campos et al. 2019). Furthermore, a year after participating in the program, the caregivers continued to have lower perceptions of burden than they did before participating in the program (Ferreira et al. 2017). Thus, it seems that this program leads to both immediate and longer-term results in relation to caregivers’ perceptions of burden, even though the elderly care recipient’s needs increased, due to the progression of the disease.

However, various questions remain. What do the caregivers learn, during the program? Are changes in their knowledge and skills related to changes in their well-being? Do preprogram differences among the caregivers with respect to their knowledge and skills affect how much they learn during the program?

Purpose

Considering the ComTato program’s promising results and the importance of understanding whether this intervention model is valid and who can be helped using this program, the two general objectives of this study were to (a) evaluate relationships between caregivers’ program-related gains and changes in their well-being and (b) analyze the influence of the caregivers’ initial repertoire on the magnitude of the improvements they experienced. More specifically, our objectives were to ascertain if (a) learning about five topics (dementia, stress management, general principles of social skills, specific social skills, and how to use cognitive stimulation to enable more positive interactions with the care recipient) affects caregivers’ use of constructive coping strategies, perceptions of burden, and the quality of the relationship with their dependent older family member and (b) if the caregivers’ initial repertoire in the five areas of the program influences the extent to which they learn new information and skills and report improvements in their use of coping strategies and in their socioemotional well-being.

Method

Study Design

The ComTato program was evaluated using a single group (all participants were offered the intervention program), pre- and posttest, quasi-experimental design (Rueda and Zanon 2016). That is, before and after participating in the program, we evaluated the caregivers’ knowledge about the five topics addressed in the program, their use of constructive coping strategies, perceptions of burden, and the quality of the relationship between the caregivers and their dependent, older relative.

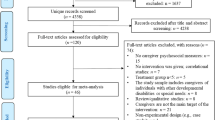

Participants

To be included in the study, caregivers had to (a) speak Portuguese, (b) be at least 18 years of age, (c) be caring for an elderly relative who had a probable diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, and (d) be available to attend sessions for the program. We recruited caregivers with the support of health professionals, who provided a contact list of potential participants. We contacted these caregivers by phone to confirm that they were caring for a relative with Alzheimer’s disease, before inviting them to participate in the study.

In total, 45 caregivers were contacted, between 2013 and 2017, of whom 40 agreed to participate and 37 finished the program. The caregivers who completed the program ranged in age from 24 to 74 years of age and resided in Brazil, in either a medium-sized city in the state of São Paulo or in a small-sized city in the state of Minas Gerais. The participants’ sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Instruments

Sociodemographic Questionnaire

This instrument was used to describe the composition of the sample, in terms of sex, age, marital status, educational level, number of children, years as a caregiver, and kinship between the care recipient and the caregiver.

Knowledge and Skills Test

This instrument was used to evaluate the caregivers’ knowledge and repertoire in relation to the following topics: (a) Alzheimer’s disease; (b) coping with stress; (c) social skills: general concepts; (d) social skills: giving positive feedback to others, offering constructive criticism, and asking for help; and (e) how to use cognitive stimulation to enable more positive interactions with the care recipient (Campos et al. 2019). The test is tailored to evaluate the knowledge and skills that are addressed in the ComTato program. It includes both multiple-choice and open-ended questions and has a scoring key. To give equal weight to each of the five topics that comprise the program, even though the number of questions is not the same for each area, points were added up separately for each topic and then converted to a proportional value, on a scale from one to ten. Each participant’s total score was calculated by adding these five scores, with a maximum total score of 50 points.

Folkman and Lazarus’ Ways of Coping Questionnaire (Folkman and Lazarus 1985)

This instrument was adapted for use in Brazil by Savóia et al. (1996). The objective of this questionnaire is to measure the coping strategies the respondent uses to deal with stress, considering a specific situation from their own lives. The original instrument includes 66 questions; however, to analyze the effects of the program, 25 questions related to coping strategies addressed by the program were selected (1, 2, 4, 8, 14, 15, 19, 20, 22, 23, 26, 30, 33, 38, 39, 40, 42, 43, 45, 47, 50, 52, 56, 62, and 64). The version used by Savóia et al. (1996) has eight factors with acceptable test-retest consistency (values between .40 and .70).

Zarit Burden Interview

This instrument is used to evaluate caregivers’ perceptions of burden (Zarit, Reever and Bach-Peterson, 1980). It contains 22 questions, divided into three factors: “Role-related stress” (α = .87); “Intra-psychic stress” (α = .78); and “Competencies and expectations” (α = .65) (Bianchi et al., 2016; Queluz et al. 2019b). The internal consistency of the Brazilian version of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) was excellent (α = .87) and there is evidence of convergent validity between scores on the ZBI and results obtained from instruments that measure emotional discomfort, such as the Behavioural and Mood Disturbance Scale (r = .54, p = .001) (Scazufca 2002).

Dyadic Relationship Scale (Sebern and Whitlatch 2007)

Translated by Thomazatti and Barham (2010), this scale evaluates the quality of the relationship between the caregiver and care-recipient and has a version for each member of the dyad (Queluz et al. 2018). Only the caregiver version was used. This 11-item instrument has two factors: (a) positive interactions (α = .77) and (b) conflict (α = .81), and this structure has been confirmed for the caregiver version of the Dyadic Relationship Scale (DRS), in Brazil (CFI = .90, RMSE = .08, and 𝜒2/df = 2.27) (Queluz et al. 2018).

Data Collection Procedure

During the 5-year period when data were collected, two principle researchers were responsible for managing the program, including tasks such as recruiting participants, training and supervising students who delivered the program, and preparing and organizing all study and intervention materials. A third researcher helped with training and supervising the students, in 2016 and 2017.

We met with the caregivers individually at their home or at their neighborhood health center, as they preferred. During the first session, the caregivers completed the study instruments. After finishing the intervention program, the caregivers completed these instruments, again, except for the Sociodemographic Questionnaire.

ComTato is an intervention program based on a cognitive-behavioral approach to helping caregivers increase their use of interpersonal skills (emotional self-regulation and social skills) and problem-focused coping strategies. Activities are used to modify the caregivers’ behavior, substituting ineffective behaviors for more adaptive ones, considering the demands of caring for an elderly person who has dementia.

Program delivery requires an average of eight, 1-h sessions. The first and last sessions are used for the pre- and posttests. In the second and third sessions, the caregiver learns concepts about Alzheimer’s disease, coping, and social skills. In the fourth and fifth sessions, the caregiver learns how to apply the concepts learned in previous sessions, considering unsuccessful interactions they are having with the care recipient or with other people involved in the caregiving context. The participant simulates using skills to provide positive feedback to others, give constructive criticism, and ask for help. The healthcare professional gives the caregivers feedback on their performance, and they repeat the simulation until they present a good-quality performance on these tasks. They are also asked to practice using these skills, at home. In the sixth and seventh sessions, theoretical and practical strategies are used to help the caregivers understand and apply ideas related to cognitive stimulation. Each caregiver tests out ways to engage in more positive interactions with the care recipient, especially when the person with AD presents behaviors that are stressful for the caregiver.

One of the resources the program uses is standardized PowerPoint presentations (which include instructions for skill-building tasks), allowing for greater methodological control. However, during the program, the caregivers are asked to describe their experiences and to plan coping strategies that are appropriate to their own situation. At the end of each module, the caregivers receive a pamphlet with a summary of the main points discussed, allowing the caregiver to (a) share the information with other family members or other caregivers and (b) review the content, during or after the intervention program.

Data Analysis Procedures

Due to the time-consuming process involved in collecting data, the number of participants in this study was low, to precisely estimate the magnitude of the relationships we examined (Dancey and Reidy, 2019). However, given that data collection was conducted in person, there was no missing data. We calculated the average, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, total, and subscale (or factor) scores for each instrument, for the pre- and posttests. The analyses involved 13 variables, considering scores for each factor and the total score for each instrument.

The normality of the distribution of scores for each measure was evaluated (Marôco 2014). The following variables had an approximately normal distribution of observations: the total score on the measure of knowledge and skills, scores on the subtest about using specific social skills (providing positive feedback, criticizing, and asking for help), coping, and the conflict subscale of the Dyadic Relationship Scale. When both variables had a normal distribution of observations, Pearson’s bivariate correlation was used (r). When at least one of the two variables did not meet the criteria for a normal distribution, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used (rho). The strength of the correlations was interpreted as weak for values < .30, moderate for values between .30 and .59, and strong for values over .60 (Levin and Fox 2004). The software we used was SPSS Statistics 20.

First, we examined whether changes in the caregivers’ repertoire of knowledge and skills (considering changes from the pretest to the posttest in their scores on each of the five topics evaluated) were associated with changes in the frequency of their use of constructive coping strategies, in their perceptions of burden, and in the quality of their relationship with their elderly relative. Next, we examined effects of prior knowledge and skills on how much the participants benefitted from the program, by examining the relationship between the caregivers’ initial repertoire of knowledge and skills and changes in their use of constructive coping strategies, perceptions of burden, and in the quality of the caregiver-care recipient relationship.

Ethical Procedures

Recruitment of participants occurred after the research project was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Research of the Federal University of São Carlos (reference numbers 503.726 and 1.403.186). Before starting the pretest, the caregivers signed an informed consent form, affirming that they understood the objectives of the study, the procedures it entailed, their rights as participants (including anonymity), and authorizing that their data be analyzed to prepare research reports and publications. Apart from the benefits of participating in the ComTato program, caregivers did not receive any other incentives or compensation for participating in the study, in accordance with Brazilian research ethics policies.

Results

Contributions of Learning New Knowledge and Skills to Changes in the Participants’ Socioemotional Well-being

When we examined correlations between changes in participants’ knowledge and skills in each of the five areas examined (dementia, stress management, general principles about social skills, understanding and use of specific social skills, and understanding and use of cognitive stimulation) and changes in their use of constructive coping strategies, perceptions of burden, and the quality of their relationship with their dependent, elderly relative, we found three statistically significant correlations. The first was a positive correlation between improvements in the total score on the measure of knowledge and skills (considering all five areas) and increases in the frequency with which they used constructive coping strategies (r = .30, p = .037). There was an even stronger positive correlation between improvements in their understanding and use of the three social skills we worked on during the program (providing positive feedback, criticizing, and asking for help) and improvements in coping (r = .36, p = .014). That is, the caregivers who learned the most in relation to the themes discussed during the program were also those with the greatest increases in their use of constructive strategies to cope with stress.

Third, we found a negative correlation between changes in scores on the subtest about general concepts of social skills, and changes in the frequency of the caregiver’s conflicts with the care recipient, which is a subscale of the Dyadic Relationship Scale (rho = − .28, p = .048). Caregivers who learned more in relation to general concepts about social skills were also those who reported a greater reduction in the frequency of conflicts with their dependent, elderly relative, after participating in the ComTato program. Note that improvements that involved a reduction in conflict scores, by the end of the program, led to change scores with negative values, as the pretest score for conflicts was higher than the posttest score. That is, the more negative the change score for conflicts, the greater the reduction of conflicts. Thus, developing a better understanding of social skills appears to have contributed to the effectiveness of the program. All other correlations analyzed were not statistically significant.

Relations Among Participants’ Initial Repertoire and Relationship Quality, and Changes in Their Socioemotional Well-being

Next, correlations were examined to investigate whether the caregivers’ initial knowledge and skills (based on their pretest scores) were related to the extent of the changes we observed in the caregivers’ well-being (considering changes in their use of constructive coping strategies, perceptions of burden, and relationship quality). Although all the participants seemed to learn something from the program, some learned more than others.

When examining changes in well-being related to conflicts (an indicator of relationship quality), a positive correlation indicates that the lower the caregiver’s initial scores (that is, the less developed his or her initial knowledge and skills), the more negative and lower the value of the change score for conflicts (that is, the greater the reduction in conflicts, by the end of the program). Negative relationships for all the other variables indicate that the lower the caregiver’s initial scores (the more restricted his or her initial knowledge and skills), the greater were the improvements in his or her well-being, by the end of the program. Seven of the correlations we tested were statistically significant and of moderate strength. Only these statistically significant correlations are presented in Table 2.

Considering the results presented in Table 2, the caregivers’ initial repertoire and relationship problems were associated with the amount the caregivers benefitted from the ComTato program. For example, the caregivers who started out with more limited knowledge about stress management reported greater reductions in levels of conflict with the elderly person they cared for, by the end of the intervention program. Furthermore, caregivers who started out with less knowledge about dementia and social skills and, more generally, about all the concepts and skills that were dealt with in the ComTato program (total score for knowledge and skills) reported greater increases in the positivity of their interactions with the dependent elderly person, at the end of the intervention program.

In relation to their social skills and relationship quality, we observed that the less proficient the caregivers were, initially, at providing positive feedback to others, offering constructive criticism, and asking for help, the more they improved their use of constructive strategies for coping with stress. In addition, the caregivers who reported higher levels of conflict with the older person they cared for, before participating in the program, reported greater increases in their use of constructive coping strategies and greater improvements in the quality of their interactions with the care recipient, in comparison with caregivers who reported a lower initial frequency of conflicts.

Discussion

Researchers have suggested that intervention programs for caregivers should focus on facilitating access to information, teaching constructive coping strategies for dealing with stress, and developing skills that favor a healthier relationship between the caregiver and the elderly care recipient (De Cola et al. 2017; Pinto et al. 2016; Queluz et al. 2018; Queluz et al. 2019b; Simonetti and Ferreira 2008) aiming to preserve the caregivers’ mental and socioemotional health (Monteiro et al. 2018). The ComTato program was developed to include all these components. In this study, we sought to understand which of these program components contributed to improvements in the participants’ socioemotional health, and then to identify which participants showed the greatest positive changes.

Relationships Between Process and Outcomes

With respect to our first objective, we observed a significant association between the knowledge acquired by caregivers and how much they (a) reduced the frequency of conflicts with the elderly care recipient and (b) increased their use of constructive coping strategies. We hypothesize that this happened because the caregivers developed their repertoire of social skills and coping strategies, within the context of assisting a family member with Alzheimer’s disease. This helped them to interact more constructively with other people involved in the caregiving context, which also favored a reduction in conflicts. For example, if a caregiver learned to ask family members for help more assertively, this may have led to greater ease in obtaining the social support they needed. This support could help them feel less burdened and provide opportunities for them to talk about emotional and practical day-to-day issues with someone else, helping them to avoid a buildup of anxiety or tensions (Ximenes 2018).

Additionally, it may be that the participants’ score on the subtest of specific social skills (providing positive feedback, criticizing, and asking for help) was the most strongly related to their use of constructive coping strategies because using these social skills is helpful for encouraging other people to act in ways that contribute to solving problems. For example, commenting on a family member’s positive behavior can improve a problematic situation by creating a stronger bond with this person and by providing social reinforcement for this behavior, increasing the probability that the family member will repeat this behavior, in the future (Del Prette and Del Prette 2017). Likewise, criticizing a family member’s behavior (or his or her lack of involvement) and then asking for a change in that behavior, discussing options for change, and deciding upon a better strategy are also important for solving problems (Ferreira et al. 2017; Campos et al. 2019).

The potential link between social skills and problem-solving could also explain the correlation between participants’ scores on the subtest on general concepts about social skills and the conflict factor of the Dyadic Relationship Scale. During the social skills modules of the intervention program, caregivers were encouraged to think about ways to integrate their own needs and objectives with the elderly care recipient’s needs, rather than ignoring either their own or the other’s needs. In the social skills component of the “Knowledge and Skills Test,” the caregivers’ repertoire was evaluated, and in the Dyadic Relationship Scale, their ability to use these skills to resolve and avoid conflicts was assessed (Pinto et al. 2016; Queluz et al. 2018).

Individual Differences in Pre-existing Repertoire and Relationship Quality

The second objective of this study was to examine the relationship between the caregivers’ initial conditions and the benefits they accrued from the program. Although all the caregivers experienced at least some benefits, those with the least knowledge and skills and the greatest number of conflicts with the care recipient, before starting, were those who improved the most, especially in terms of the use of constructive coping strategies and increases in the quality of their relationship with their dependent, elderly family member. The less the caregivers knew and the less well developed their skills, initially, the more they could learn; the more they learned, the more they changed their behaviors. Thus, when the caregivers learned more about dementia and about strategies to manage difficult caregiving situations, their relationship with their elderly family member improved.

This result confirms that an important task in psychoeducational programs is to ensure that the caregivers come to understand that many of the behaviors that their elderly family member presents are influenced by having dementia. Given that we do not yet have a cure for Alzheimer’s disease, the stress the caregiver feels and the interpersonal problems that arise in response to their family member’s behavior need to be managed using constructive coping strategies (Gilhooly et al. 2016; Pinto and Barham 2014). Furthermore, to achieve social competency, it is essential for the caregivers to understand their relative’s situation. When the caregivers have social skills that can contribute to the quality of the dyadic relationship, they can avoid responding to their family member with aggression, especially when their elderly relative is being aggressive (Barham et al. 2015).

Based on the association we observed between gains in social skills and improvements in coping, we can indicate that caregivers’ relationships with the care recipient and with other family members may be improved by helping them to make better use of opportunities to give positive feedback to others when they are helpful (by expressing positive emotions) or by starting conversations about how to adapt caregiving efforts as the family member’s illness progresses, by giving and receiving constructive criticism and by asking for help. A greater repertoire of interpersonal skills helps people to engage in better quality interactions that provide everyone with more positive reinforcements (Barham et al. 2015; Pinto, Barham and Albuquerque, 2013).

Apart from their social skills, another factor that affected program gains involved pre-existing differences in the caregivers’ level of conflict with the dependent elderly person they were assisting. The ComTato program seems to have had a stronger influence on increasing the caregivers’ use of constructive coping strategies and the frequency of positive interactions among caregivers who were experiencing more frequent conflicts with the care recipient, before starting the program. Considering that one of the goals of the program was to teach caregivers to substitute non-adaptive behaviors for adaptive ones, it may be that these caregivers not only reduced the frequency of conflicts with the care recipient, but that they substituted at least some negative responses with more positive ones by using more constructive coping strategies, like describing how another family member’s help would be important.

In relation to the implications of the present study, we suggest that the results demonstrate the importance of helping caregivers work on their social skills, in the context of caring for someone with Alzheimer’s disease. This kind of support seems to help caregivers to cope more constructively and to improve their relationship with their elderly family member. In addition, these data suggest that the ComTato program is a promising psychoeducational intervention program, especially for people with greater initial interpersonal difficulties. That is, the ComTato program seems to be most helpful for those who need help the most. Furthermore, these results reinforce Kishita et al.’s (2018) findings, based on a systematic review, indicating the importance of psychoeducational, skill-building interventions founded on cognitive-behavior therapy models that address the context faced by caregivers who assist elderly people with dementia.

This study also contributes to the construction of a theoretical model of interpersonal processes in the caregiving context. We examined caregivers’ initial circumstances, in terms of coping strategies, social skills (especially positive feedback, discussing problems, asking for help, and general concepts about social interactions), knowledge about the care recipient’s needs (in this case, due to Alzheimer’s disease), and the quality of the relationship between the caregiver and the care recipient. We found that improvements in their knowledge and skills in these areas are related to improvements in their socioemotional well-being, resulting in greater use of constructive coping strategies, fewer conflicts, and more positive interactions in their relationship with the care recipient. That is, the present study contributed to the identification of important variables related to the context of care, showing that it is possible to help caregivers improve their interpersonal relationships using intervention programs.

Our findings also fit with previously developed theories, such as the motivational coping theory. This theory states that coping involves relating to other people, interacting positively with the environment, and choosing one’s course of action. The skills we focused on in the ComTato program and the outcomes we evaluated address these constructs, and thus, our results can serve as evidence to support and strengthen this theory. In addition, because the ComTato program is based on a model of cognitive-behavioral education, our results reinforce Zarit’s (2017) and Kwon et al.’s (2017) findings on the potential of intervention programs for caregivers, when they are based on the principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Although some of the predicted results were encountered, many expected associations were not found, especially those between changes in the caregivers’ knowledge and skills and changes in their perceptions of burden. This was surprising, as perceptions of burden did improve for most of the caregivers who participated in this program and did not return to preprogram levels, even after a 1-year interval (Ferreira and Barham 2016; Ferreira et al. 2017). In addition, in other studies, a significant correlation between social skills and burden was observed among those caring for an elderly family member (Pinto and Barham 2014; Queluz et al. 2019b).

It is likely that it would take people some time to be able to use coping strategies that require gradually discovering, through trial and error, how to change their behavior to get better results. Similarly, it is not easy to change how we interact with other people in stressful situations, especially when the caregivers also need to encourage those around them to change their behaviors (Gilhooly et al. 2016; Monteiro et al. 2018). In future studies, it would be useful to evaluate how much and how well caregivers use the skills that they worked on during the intervention program, after the program finished, to better understand how the use of these skills affects perceptions of burden, in the long term.

Another factor that may have affected the number and strength of the correlations we found was a ceiling effect (Pinquart and Sörensen 2006). The instrument we used to evaluate the caregiver’s knowledge and skills was not fine-grained, such that improvements among caregivers with repertoire in the moderate to strong range were poorly differentiated, especially with respect to knowledge about dementia. Thus, relationships among gains in knowledge and skills, on the one hand, and improvements in the socioemotional health of the caregivers, on the other hand, might have been more numerous and of a higher magnitude if we had used an instrument that was more precise for evaluating differences among caregivers with knowledge and skills in the moderate to high range. This does not change the fact, however, that caregivers who started with a more restricted range of knowledge and skills did make significant and measurable gains.

In light of the results and discussion above, and considering the importance of developing more and better intervention programs in the future, we highlight the importance of developing good-quality instruments that make it possible to examine how the specific types of knowledge and skills that are worked on in a psychoeducational intervention program can contribute to participants’ socioemotional well-being, and to evaluate whether the participants have gaps in their initial repertoire that will be addressed in the program. The results of this study validate the idea that helping people expand or adjust their psychological repertoire to manage new demands can favor positive results, even when these people are older adults (Monteiro et al. 2018).

In addition, given that there are differences in the initial repertoire of people who participate in psychoeducational programs, and that most skills can be learned or improved (Gilhooly et al. 2016; Silva, Dantas, Nascimento, Melo, Haydu and Pimentel, 2018; Simonetti and Ferreira 2008), one way to increase the effectiveness of intervention programs would be to organize them in modules of increasing complexity, so that the “starting point” can be adjusted, depending on the participant’s initial knowledge and skills.

Conclusion

This study was innovative because it looked at the relationship between program-related gains in psychological knowledge and skills and people’s socioemotional well-being. This is important because it shows how learning—in this case, learning about an illness and about adaptive coping strategies and social skills that are relevant to that context—can influence the quality of interpersonal relationships, in this case, a relationship with a dependent elderly person (Queluz et al. 2018). At a more general level, the results support the idea that adults who currently have more limited knowledge or skills can increase their abilities to interact with other people by increasing their understanding of the interpersonal situation they are facing, improving their skills to deal with their negative feelings, and expanding their skills to maintain relationships (by discussing problems and suggesting changes), and to strengthen relationships (by recognizing other people’s contributions), and these improvements are related to important changes in their socioemotional health. Thus, this study’s contributions go beyond a specific intervention targeted at caregivers for dependent elderly people, by providing information that is relevant to understanding mechanisms of socioemotional change in adults. In addition, we provide an example of how to evaluate the connection between the process of change and the effectiveness of psychological interventions, for any population, at any stage of life.

One limitation of our study, however, was the sample size, and the fact that all the caregivers were recruited in one of two cities in the southwest region of Brazil. Possibly, the sample size made it difficult to find other statistically significant correlations that may exist, but which were not captured in the present study. It would be interesting to use the ComTato program in other locations and to build a data bank with results for a larger number of participants to verify if the current results are maintained, and if the non-significant results, such as those regarding burden, would become significant when analyzed with a more diverse sample (Marôco 2014).

In future studies, it would also be important to ascertain if there are other variables, in addition to those examined here, that might influence the effectiveness of psychoeducational programs such as the ComTato program. For example, factors such as caregiver depression, how advanced the elderly person’s dementia is, and the availability of social support (provided by other family members or paid caregivers) may also affect program outcomes.

Finally, according to Queluz et al. (2019a) and De Cola et al. (2017), when caregivers were asked about the types of information or support they need, they said they needed educational programs that could help them develop better ways of dealing with their family member’s illness. Although more precise measures of program gains are needed, the evidence we have examined indicates that the ComTato program contributes to meeting this need. Therefore, this program should be evaluated with a larger and more diverse sample, to gain more extensive evidence about the effectiveness of the behavioral change mechanisms used in this program and to refine information about who can benefit from this program. A more robust body of evidence will provide information about how to improve the program. It will also help to determine when mental health professionals who assist those who care for the elderly could use the program, to help caregivers maintain better quality relationships and make better use of constructive ways of responding to the complex situations they are facing.

Notes

Initially, the ComTato program was named the Programa dos 3Es (P3Es), in Portuguese, and was referred to as the “3Cs Program” (3CP), in English.

References

Alvira, M. C., Risco, E., Cabrera, E., Farré, M., Rahm Hallberg, I., Bleijlevens, M. H. C., Bleijlevens, M. H. C., Meyer, G., Koskenniemi, J., Soto, M. E., Zabalegui, A., & The RightTimePlaceCare Consortium. (2015). The association between positive–negative reactions of informal caregivers of people with dementia and health outcomes in eight European countries: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(6), 1417–1434. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12528.

Amador-Marín, B., & Guerra-Martin, M. D. (2017). Eficacia de las intervenciones no farmacológicas en la calidad de vida de las personas cuidadoras de pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer. Gaceta Sanitaria, 31(2), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.09.006.

Ambriz, M. G. J., Izal, M., & Montorio, I. (2012). Psychological and social factors that promote positive adaptation to stress and adversity in the adult life cycle. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(5), 833–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9294-2.

Barham, E. J., Pinto, F. N. F. R., Andrade, A. R., Lorenzini, M. F. J., and Ferreira, C. R. (2015). Fundamentos e estratégias de intervenção para a promoção de saúde mental em cuidadores de idosos. In: S. G. Murta, C. Leandro-França, K. B. Santos, and L. Polejack, (Orgs.). Prevenção e promoção em saúde mental: Fundamentos, planejamento e estratégias de intervenção, (pp. 844-862). Novo Hamburgo, RS: Sinopsys.

Bianchi, M., Flesch, L. D., Alves, E. V. C., Batistoni, S. S. T., & Neri, A. L. (2016). Indicadores psicométricos da Zarit Burden Interview aplicada a idosos cuidadores de outros idosos. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 24(e2835), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518-8345.1379.2835.

Campos, C. R. F., Carvalho, T. R., Barham, E. J., Andrade, L. R. F., & Giannini, A. S. (2019). Entender e envolver: avaliando dois objetivos de um programa para cuidadores de idosos com Alzheimer. Psico, 50(1), e29444. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-8623.2019.1.29444.

Dancey, C. P., & Reidy, J. (2019). Estatística sem Matemática para Psicologia (7th ed.). Porto Alegre: Artmed.

De Cola, M. C., Lo Buono, V., Mento, A., Foti, M., Marino, S., Bramanti, P., et al. (2017). Unmet needs for family caregivers of elderly people with dementia living in Italy: what do we know so far and what should we do next? The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 54, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0046958017713708.

Del Prette, Z. A. P., & Del Prette, A. (2017). Habilidades Sociais e Competência Social para uma vida melhor. São Carlos, SP: EDUFSCar.

Ferreira, C. R. (2014). Ensinando cuidadores de idosos com doença de Alzheimer a usar estratégias de enfrentamento de estresse e estimulação cognitiva. In Monografia, Programa de Pós Graduação em Psicologia. Brasil: Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos.

Ferreira, C. R. (2015). Ensinando cuidadores de idosos com doença de Alzheimer a usar estratégias de enfrentamento de estresse e estimulação cognitiva. Relatório Final de Iniciação Científica, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, Brasil.

Ferreira, C. R., and Barham, E. J. (2016). Uma intervenção para reduzir a sobrecarga em cuidadores que assistem idosos com doença de Alzheimer. Revista Kairós Gerontologia, 19(4), 111-130. Available in https://revistas.pucsp.br/index.php/kairos/article/view/31645/22037

Ferreira, C. R., Queluz, F. N. F. R., Ximenes, V. S., Isaac, L., & Barham, E. J. (2017). P3Es e a diminuição da sobrecarga em cuidadores: Confirmando efeitos em curto e longo prazo. Revista Kairós – Gerontologia, 20(3), 131–150. https://doi.org/10.23925/2176-901X.2017v20i3p131-150.

Folkman, S., and Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: a study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 150-170. Available in https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2980281.

Gilhooly, K. J., Gilhooly, M. L. M., Sullivan, M. P., McIntyre, A., Wilson, L., Harding, E., Woodbridge, R., & Crutch, S. (2016). A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatrics, 16(106), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8.

Kishita, N., Hammond, L., Dietrich, C. M., & Mioshi, E. (2018). Which interventions work for dementia family carers? An updated systematic review os randomized controlled trials of carer intervention. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(11), 1679–1696. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610218000947.

Kwon, O. Y., Ahn, H. S., Kim, H. J., & Park, K. W. (2017). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for caregivers of people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of clinical neurology (Seoul, Korea), 13(4), 394–404. https://doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2017.13.4.394.

Levin, J., & Fox, J. A. (2004). Estatística para ciências humanas. São Paulo, SP: Pearson.

Marôco, J. (2014). Análise estatística com o SPSS Statistics. Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal: Report Number.

Monteiro, A. M. F., Santos, R. L., Kimura, N., Baptista, M. A. T., & Dourado, M. C. N. (2018). Coping strategies among caregivers of people with Alzheimer disease: a systematic review. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 40(3), 258–268. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2017-0065.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2006). Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: which interventions work and how large are their effects? International Psychogeriatrics, 18, 577–595. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610206003462.

Pinto, F. N. F. R., & Barham, E. J. (2014). Bem-estar psicológico: Comparação entre cuidadores de idosos com e sem demência. Psicologia, Saúde and Doenças, 15(3), 635–655. https://doi.org/10.15309/14psd150307.

Pinto, F. N. F. R., Barham, E. J., and Albuquerque, P. P. (2013). Idosos vítimas de violência: fatores sociodemográficos e subsídios para futuras intervenções. Estudos e Pesquisas em Psicologia, 13(3), 1159-1181. (doi nonexistent).

Pinto, F. N. F. R., Barham, E. J., & Del Prette, Z. A. P. (2016). Interpersonal conflicts among family caregivers of the elderly: the importance of social skills. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 26(64), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-43272664201605.

Queluz, F. N. F. R., Barham, E. J., Santis, L., Ximenes, V. S., & Santos, A. A. A. (2018). Escala de Relacionamento da Díade: Evidências de validade para cuidadores de idosos brasileiros. Psico, 49(3), 294–303. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-8623.2018.3.28227.

Queluz, F. N. F. R., Campos, C. R. F., Santis, L., Isaac, L., & Barham, E. J. (2019a). Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview: Evidencias de validez para la población brasileña de cuidadores de ancianos. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 28(1), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.15446/rcp.v28n1.69442.

Queluz, F. N. F. R., Kervin, E., Wozney, L., Fancey, P., McGrath, P. J., & Keefe, J. (2019b). Understanding the needs of caregivers of persons with dementia: a scoping review. International Psychogeriatrics, 1, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610219000243.

Rueda, F. J. M., & Zanon, C. (2016). Delineamento correlacional: Definições e aplicações. In M. N. Batista & D. C. Campos (Eds.), Metodologias de pesquisa em ciências: Análises quantitativa e qualitativa (pp. 115–124). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: LTC.

Savóia, M. G., Santana, P., & Mejias, N. P. (1996). Adaptação do Inventário de Estratégias de Coping de Folkman e Lazarus para o português. Revista Psicologia USP, 7(1–2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-51771996000100009.

Scazufca, M. (2002). Versão brasileira da Escala de Burden Interview para avaliação de sobrecarga em cuidadores de indivíduos com doenças mentais. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 24(1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462002000100006.

Sebern, M. D., & Whitlatch, C. J. (2007). Dyadic Relationship Scale: a measure of the impact of the provision and receipt of family care. The Gerontologist, 47, 741–751. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/47.6.741.

Silva, K. P., Dantas, L. Z., Nascimento, A. R., Melo, C. M., Haydu, V. B., and Pimentel, N. S. (2018). Repertório Comportamental: Uma Reflexão Sobre o Conceito. Comportamento em foco, 7, 155-164. (doi nonexistent).

Simonetti, J. P., & Ferreira, J. C. (2008). Estratégias de coping desenvolvidas por cuidadores de idosos portadores de doença crônica. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 42(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-62342008000100003.

Thomazatti, A. P. G., & Barham, E. J. (2010). Integrando medidas qualitativas e quantitativas Para avaliar a qualidade do relacionamento mãe-idosa e filha-cuidadora. Apresentação Oral no XVII Congresso de Iniciação Científica. São Carlos, SP: Universidade Federal de São Carlos.

Tomomitsu, M. R. S. V., Perracini, M. R., & Neri, A. L. (2014). Fatores associados à satisfação com a vida em idosos cuidadores e não cuidadores. Ciência and Saúde Coletiva, 19(8), 3429–3440. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232014198.13952013.

Van der Lee, J., Bakker, T. J. E. M., Duivenvoorden, H. J., & Droes, R. M. (2014). Multivariate models of subjective caregiver burden in dementia: a systematic review. Ageing Research Reviews, 15, 76–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2014.03.003.

Wong, C. S. C., & Zelman, D. C. (2019). Caregiver expressed emotion as mediator of the relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia patients and caregiver mental health in Hong Kong. Aging & Mental Health, 5, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1636200.

Ximenes, V. S. (2018). Um estudo correlacional entre habilidades sociais, suporte social e qualidade de vida em cuidadores familiares de idosos (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal de São Carlos. SP: São Carlos.

Zarit, S. H. (2017). Past is prologue: how to advance caregiver interventions. Aging & Mental Health, 22(6), 717–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1328482.

Zarit, S.H., Reever, K.E., and Bach-Peterson, J. (1980). Relatives of the impaired elderly correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist, 20, 649-655. Available in http://gerontologist.oxfordjournals.org

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Skinner, E. A. (2009). Coping, development influences. In H. T. Reis & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships. Newbury: Sage.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP Grant #2017/24026-0).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C. Campos, T. Carvalho, and F. Queluz wrote the manuscript with assistance from A. Setti and E. Barham. C. Campos conducted data collection with support from T. Carvalho and E. Barham. C. Campos and E. Barham analyzed the data and interpreted the findings. Moreover, C. Campos and E. Barham are the co-authors of ComTato. All authors provided substantive edits, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics Approval

This manuscript was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Carlos, reference numbers 503.726 and 1.403.186.

Consent to Participate

All participants signed an informed consent form, affirming that they understood the objectives of our project, the procedures it entailed, and their rights as participants.

Consent for Publication

In the informed consent form, there was a clause regarding consent to publish their data anonymously, which all participants also agreed to.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Campos, C.R.F., de Carvalho, T.R., Queluz, F.N.F.R. et al. Process and Outcomes: the Influence of Gains in Knowledge and Socioemotional Skills on Caregivers’ Well-being. Trends in Psychol. 29, 67–85 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-020-00044-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-020-00044-0