Abstract

The field of social work is increasingly recognizing and supporting the role of family caregivers as vital members of the health care team who also need support. Demands on caregivers of individuals living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) are enormous, and there remains a significant lack of measurement tools for social work clinicians to evaluate caregiver well-being in medical settings. This study reviews the development and initial psychometric properties of the Caregiver Outcomes of Psychotherapy Evaluation (COPE), a pre- and post- treatment outcome measure designed to assess and monitor the individualized needs of caregivers for individuals living with ADRD. The COPE is comprised of eight questions that assess knowledge of dementia, confidence in caregiving abilities, communication strategies, emotional well-being, support system, planning for the future, enjoying life, and confidence facing future challenges. The COPE was administered to 85 caregivers prior to the start of counseling sessions. Responsiveness to intervention, inter-item reliability and convergent/divergent validity with existing measures such as the Zarit Burden Inventory and Geriatric Depression Scale were explored. The COPE demonstrated adequate to good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .73), as well as evidence of convergent validity with caregiver reported burden (r = .37, p < .05). These findings offer preliminary support that the COPE is a brief and valid measure for social workers to use to evaluate caregiver needs in clinical settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social workers are in a unique position to provide counseling and care management services to address the complex needs of individuals with dementia and their caregivers within the healthcare system and extending into the community. Demands on caregivers of individuals living with Alzheimer disease and related dementias (ADRD) are enormous, with an estimated 18 billion hours of unpaid care provided in 2022 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2023). Caregivers often report high levels of depression and anxiety, with spousal caregivers being two and a half times more likely to be depressed than non-spousal caregivers (Sallim et al., 2015). Caregivers also often experience significant psychosocial stressors and describe reduced social support and increased uncertainty about the future, especially associated with long-term care planning (Cheng, 2017; Gaugler et al., 2019; Nikzad-Terhune et al., 2019).

While often lumped together, caregivers are a heterogeneous group of individuals that have unique goals, needs, and preferences for care and support. As described in a Special Report on Race, Ethnicity and Alzheimer’s in America, dementia caregiving is common across all racial and ethnic backgrounds, however, dementia disproportionately affects Black Americans (2X) and Hispanic Americans (1.5X), and their caregivers are more likely to report facing discrimination in the healthcare system (61% and 56% respectively) (Alzheimer’s Association, 2021). Additionally, a recent meta-analysis found Hispanic dementia caregivers reported lower physical well-being than White dementia caregivers; while Black dementia caregivers exhibited higher psychological well-being than White dementia caregivers (Liu et al., 2021). Therefore, to better serve diverse caregivers, we must create innovative outcome measures that capture the unique psychosocial impacts of caregiving.

Further, while negative psychosocial impacts of dementia caregiving are well documented, it is increasingly recognized that there are positive aspects of caregiving. According to the Alzheimer’s Association Facts and Figures (2023), 45% of caregivers feel that their role is very rewarding. Caregivers also report increases in confidence and sense of meaning (Cho et al., 2016). These positive experiences of dementia caregivers must not be overlooked in the development of outcome measurements that capture the strengths inherent in this population.

In addition to the considerable need for strength-based outcome measures and culturally competent interventions, the needs of caregivers are unmistakably overlooked in medical visits. While caregivers may be physically present, they are rarely asked questions about their own health and well-being (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2020), highlighting the need for innovative caregiver outcome measures that can be used in the medical setting. Furthermore, identification of caregivers in medical records, providing supportive services to caregivers and measuring caregiver outcomes within healthcare systems are processes that are still in their infancy of utilization (Borson et al., 2016; Gaugler et al., 2019; Harvath et al., 2020).

In light of both negative and positive psychosocial impacts of caregiving, the identified needs of caregivers seeking social work services vary on a case-by-case basis. For example, for any given caregiver/care recipient dyad, caregiver goals may include maintaining social relationships, exploring opportunities to engage in meaningful activities for themselves or the person they care for, support for decision-making, and increasing knowledge about dementia (Gaugler et al., 2019; Orsulic-Jeras et al., 2020; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021). As Zarit (2017) stated, “The biggest challenge in caregiver intervention research is that after all this time we still do not have a clear idea of what the goals of treatment for caregivers should be” (p.1). He pointed out that treatment fidelity is routinely assessed in psychotherapy treatment interventions, but in caregiver interventions, studies frequently neglect to answer basic questions such as, “Do caregivers now have more information about dementia or about resources? Do they know how to apply behavioral management? Do they feel more support”? (p.4). Likewise, Gallagher-Thompson et al. (2020) asserted that caregiver interventions should not be a one-size-fits-all approach; the heterogeneity of caregivers should be reflected by offering tailored services based on the specific wants and needs of an individual caregiver as determined by caregiver-centered assessments.

Given the complexity of caregiver needs and goals, calls have been made for the development of outcome measures that go beyond traditional assessment of distress and burden (Gaugler et al., 2019; Pedergrass et al., 2015; Orsulic-Jeras et al., 2020; Zarit, 2017). Specifically, there is a need for outcome measurements that capture aspects of resilience, individualized goals, and well-being (Gaugler et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2022). A recent meta-analysis including 131 studies of dementia caregiver interventions found that very few studies measured ability/knowledge, confidence, coping, and social support (Cheng et al., 2020). Further, a systemic review of 69 dementia caregiver interventions found that the two most commonly used endpoints of randomized controlled intervention studies were “depressive symptoms” and “caregiver burden” (Pedergrass et al., 2015). The National Association for Social Workers (NASW) Standards for Social Workers in Health Care Settings states that social workers are responsible for formally evaluating the effectiveness of interventions to improve patient health and well-being, highlighting the need for social work leaders to develop outcome measures that reflect critical paradigm shifts in the field (National Association of Social Workers (NASW), 2021).

In response to these calls, our team developed the Caregiver Outcomes of Psychotherapy Evaluation (COPE). The COPE is a brief questionnaire that is intended to be both a pre- (needs assessment) and post (outcome) measure that captures goals that are centered on the needs and wants of individual caregivers. Specific aims of the current manuscript are to describe the development of COPE, examine its initial psychometric properties, including internal consistency and convergent/divergent validity, and explore its sensitivity to change in response to social work interventions.

Materials and Methods

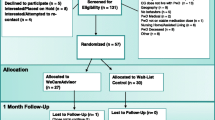

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 85 caregivers of individuals with ADRD presenting for social work psychotherapy services at an outpatient dementia specialty clinic. The average age of caregivers was 64.6 years, with approximately 65% identifying as women and 73% as spouses. See Table 1 for additional details about demographic characteristics of the sample. Participants completed the COPE and a subset of other clinical measures (described below) prior to their initial appointments as a part of their clinical intake. These measures were utilized to explore convergent validity of the COPE. In addition, a subset of 22 caregivers completed the COPE at the end of their counseling sessions. The requirement for consent was waived by our Institution, IRB approval number 2019110131.

Caregivers were offered the option to participate in psychotherapy services with a clinical social worker if they screened positive for caregiver distress on the four item Zarit Burden inventory (Bédard et al., 2001) in the care recipient’s initial medical appointment with the clinic or by request of patient or provider. Sessions in our clinic are scheduled for 45–60 min in duration, with frequency and duration of counseling based on need and mutually agreed upon goals between the social worker and caregiver, with additional sessions offered as needed. Examples of topics covered included adjustment to diagnosis, role and relationship changes, managing challenging behavioral symptoms, establishing routines, driving retirement, grief and loss, family dynamics, legal/financial issues, safety concerns, navigating the healthcare system, advance care planning, and connecting to community resources. Typical social work interventions used in our clinic and supported by research (Alzheimer’s Association, 2023; Cheng et al., 2020; Collins & Kishita, 2019; Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2020) included mindfulness-based techniques, psychoeducation, guided imagery, motivational interviewing, grief and loss therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, identification of support system, narrative therapy, solutions-focused therapy, problem-solving therapy, disease education, development of coping skills, communication skills training, and behavioral management of symptoms of ADRD.

Measures

The COPE is comprised of eight questions that assess knowledge of dementia, confidence in caregiving abilities, communication strategies, emotional well-being, support system, planning for the future, enjoying life, and confidence facing future challenges (see items in Appendix A). The questions for the COPE were derived by identifying common themes in clinical experiences working with adult caregivers that were not addressed in currently available assessments. Important considerations included developing a person-centered (vs. health system-centered) and resilience-based (vs. deficit-based) measurement that aligned with the goals of capturing what matters most to caregivers. The scale was developed by three clinical social workers (A.A., J.A., A.F.) and refined with input from clinic team members. The initial version of the questionnaire included three open-ended questions, which were ultimately discontinued to reduce survey fatigue and to keep the survey as brief as possible for application in clinical settings.

All questions are rated on a Likert scale that ranges from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree), with lower scores indicating better functioning. A total score (8–40) was also calculated by summing the individual item scores. Convergent validity was examined via administration of the Zarit Burden Inventory 4 Item Short form (ZBI-4; Bédard et al., 2001) and the Geriatric Depression Scale 15 Item Version (GDS-15; Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize item responses of the COPE and to summarize total scores of the COPE, ZBI-4, and GDS-15. Internal consistency and inter-item reliability of the COPE were evaluated by Cronbach’s alpha and inter-item Pearson correlations. Convergent and divergent validity between the COPE and its constituent items and the ZBI-4 and GDS-15 were evaluated with Pearson correlations. These measures were used because burden and depression can be important markers of psychosocial impacts of caregiving and thus some individual items should correlate with these (convergent validity), but the COPE was intended to also capture aspects of care beyond these concepts and thus other items particularly related to knowledge of dementia and planning needs may not correlate demonstrating divergent validity. Finally, an initial exploration of the responsiveness of the scale to psychotherapeutic intervention was evaluated by paired sample t-tests. Significance was set at p = 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Descriptive information for the COPE from the baseline sample as well as criterion measures of depression and caregiver burden are presented in Table 2.

Internal Consistency and Inter-Item Correlations

Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the COPE was 0.73 overall, falling in the acceptable to good range (Gliem & Gliem, 2003). Alpha with any given item excluded ranged from 0.68 to 0.74. Inter-item correlations are presented in Table 3.

Convergent and Divergent Validity

Convergent validity of the COPE with caregiver reported burden as well as depressive features is found in Table 4. As would be expected, items designed to capture overall emotional distress (i.e., emotional well-being, confidence, and overall enjoyment of life) demonstrated statistically positive significant correlations with measures of burden and depression. Conversely, items tapping knowledge and skills were unrelated to these constructs. Total score correlated modestly with caregiver burden and not depression.

Change in Response to Social Work Intervention

Caregivers completing the post-treatment questionnaires did not differ significantly from the initial visit sample (see Table 1) in terms of age, relationship to or years they had known the person with ADRD, educational level, race/ethnicity, or clinical stage of the person with ADRD. However, caregivers who completed the post-treatment questionnaire were more likely to be male (χ2(1, N = 62) = 6.01, p = 0.016) than the baseline sample.

The results of paired sample t tests between individuals with pre-post ratings are found in Table 5. Four of the eight items, confidence in caregiving, communication skills, supportive social networks, and ability to manage emotional well-being, demonstrated statistically significant improvements post-therapeutic intervention. Total score improved as well, with effect size (Cohen d = 0.893) suggesting a large effect of social work intervention as indexed by the COPE.

Discussion

The COPE is a potential solution to the call to action from national caregiving organizations (Gaugler et al., 2019; Zarit, 2017) highlighting the need for strength-based, person-centered, outcome measurements that capture caregiver needs in a simple, easy-to-use scale. To our knowledge, it is the first tool of its kind that informs social workers and other mental health professionals about specific areas to target for tailored ADRD caregiver services, such as emotional support, psychoeducation, social support, and skills training that can also serve as a counseling outcome measure. While caregivers seeking dementia specific counseling services often desire to improve their own mental health, equally important is addressing their goals of learning how to manage difficult behaviors, developing a support system, and learning new strategies to communicate with their loved one who is impacted by ADRD. This framework is emblematic of social work values and the person-in-environment perspective, which highlights the importance of understanding an individual in light of the environmental contexts in which that person lives and acts (Kondrat, 2013). Because there are adequate tools available to assess levels of burden and emotional distress, the COPE fills a gap by evaluating areas that can be built upon to tap into the caregiver’s inner strengths and resources by addressing confidence, skills, and quality of life. This manuscript describes the scale’s composition and its initial psychometric properties. We summarize these results below and provide an example of the instrument’s use in clinical practice.

Internal Consistency of the COPE

The COPE demonstrates acceptable to good inter-item reliability. In exploring inter-item correlations, it appeared that items may be clustering together in addition to providing an overall score. For example, items tapping confidence, emotional well-being, supportive networks, and preparation for future caregiving all were highly intercorrelated. Given the relatively limited sample size of this pilot study, we could not explore the structure of items in more detail, but future studies with larger sample sizes will help identify if an interpretable subscale structure will improve utilization of this instrument from a psychometric standpoint.

Convergent and Divergent Validity of the COPE

In contrast to existing measures, the COPE is intended to capture several facets of caregiving at baseline and as an outcome measure. Thus, one would expect specific items to correlate more strongly with gold-standard outcome measures, such as burden and depression. Exact criteria for establishing convergent and divergent validity statistically are noted to be somewhat arbitrary, but correlations > 0.5 are generally thought to indicate convergent validity (see review in Abma et al, 2016). However, given that the COPE instrument also taps additional domains (i.e., confidence, education, and well-being) correlations for these items in particular with measures of burden and depression may be modest. Overall, the results from our analyses conformed to this pattern. Items measuring a caregivers ability to manage their emotional well-being and enjoying life all correlated > 0.5 with the GDS-15 signifying that items designed to capture emotional distress and well-being correlated in the expected direction with criterion measures of burden and depression, while skill-based items did not. This pattern of findings supports the idea that the COPE captures the additional, multi-faceted experience of caregiving rather than unidimensional negative psychosocial ramifications. This is perhaps best illustrated by the limited correlation of the COPE total score with a measure of depression, in contrast to the individual COPE items tapping emotional well-being which correlate relatively strongly with caregiver depression.

Does this correlation mean the COPE is not a valid measure? We would argue that is not the case, as overall changes in the COPE score tracked well with use as an outcome measure for social work counselling, where changes in COPE scores result in a large effect size (Cohen’s D of 0.89). We argue this effect is preliminary evidence that the COPE is capturing the work of social work interventions which often expands much more broadly into areas such as education and community resources, beyond measures of burden and depression which were used as our comparator measures.

Overall, we believe these findings also provide initial support for the convergent and divergent validity of the measure, although further work is needed to describe these properties. Further work evaluating the potential utility and psychometric properties of subscales from the COPE may also warrant future exploration.

Response to Intervention with the COPE

Though preliminary given the small sample size, initial results suggest the COPE is responsive to changes in caregiver-focused intervention, with total scores suggesting large effects from participation in social work services. The COPE showed responsiveness in the expected direction with items addressing confidence in caregiving, communication skills, having supportive social networks, and being able to manage emotional well-being; critical skills to be developed in caregiver therapy. Larger, more diverse sample sizes and use in more controlled clinical trial settings are needed to identify important additional psychometric considerations, such as meaningfully important change and overall test–retest reliability, but initial results are promising for the instrument’s use in this setting.

Intersection with Social Work Values

Providing care to an individual with a neurodegenerative condition is not without challenges; and a review of the literature validates the physical and emotional consequences of caregiving (Alzheimer’s Association, 2023; Cheng, 2017; Gaugler et al., 2019; Nikzad-Terhune et al., 2019). While much of the attention in dementia research around outcome measures has been focused on the negative aspects of caregiving, there are recommendations to shift our attention to develop measures that capture strengths, well-being, resilience and the positive effects (Gaugler et al., 2019). Measuring outcomes such as depression, anxiety and burden are important, but it should not overshadow our responsibility to also measure strengths. Person-centered (vs. health-system centered) and resilience-based (vs. deficit-based) measurements align with social work values, including the importance of human relationships and promoting the dignity and worth of the person. A strength-based, ecological approach to measurement considers the individual and the environment in which the individual resides. Social work philosophy views clients as inherently resourceful and resilient in the face of challenging circumstances; assessment and outcome measurements with caregivers should reflect these values (National Association of Social Workers (NASW), 2021).

Examples of Use in Health Settings

The two case examples below highlight how the COPE can be used in clinical practice. In both cases, the care partner completed the COPE prior to their first counseling session, and the counselor, in this case a clinical social worker (SW), used a strength-based, motivational interviewing approach to ask scaling questions.

Case Example 1

Mrs. M.’s husband (J.M.) was diagnosed with moderate dementia due to Alzheimer disease. Mrs. M. indicated that she felt ‘neutral’ regarding “I have communication strategies that are effective with my loved one”.

SW: I see that you indicated you felt ‘neutral’ about having effective communication strategies. Why did you choose ‘neutral’ instead of ‘disagree’?

Mrs. M: Most of the time I know how to respond to J.M., but during the afternoons he gets more confused, and I get very frustrated with repetitive questions.

SW: Tell me more about what strategies you are using in the morning to help you stay calm when he asks repetitive questions.

Mrs. M: In the morning I go sit outside on the patio when I’m feeling frustrated, which helps me calm down. In the afternoon it’s too hot outside so I have nowhere to escape.

SW: Let’s come up with a plan together to identify solutions and find alternative ways to find time to yourself to reset in the afternoon.

Case Example 2

L.B.’s mother (P.J.) was diagnosed with mild Lewy Body dementia. L.B. indicated that he ‘disagreed’ regarding “I am knowledgeable about dementia”.

SW: I noticed that you indicated that you don’t feel knowledgeable about dementia. How do you feel I can best support you in this area?

L.B: I’ve read about Alzheimer’s disease, but I’ve never heard of Lewy Body dementia.

SW: Tell me more about your preferences in receiving information. For example, do you prefer online oral classes, written materials such as books, or scientific articles?

L.B.: I used to attend a support group for adult children when my mother was diagnosed with cancer. Meeting with others helped me learn more about her diagnosis and also was a source of emotional support.

SW: Are you interested in hearing about support groups for family members of Lewy Body Dementia?

These vignettes demonstrate that in addition to being a psychometrically promising measure, the tool also provides an opportunity to explore the caregiver’s counseling goals using evidence-based approaches from the initial session. The COPE is a promising measure of ADRD caregiver counseling needs and outcomes, with initial results indicating adequate internal consistency, convergent validity, and responsiveness to intervention. While caregivers may be physically present in initial diagnostic visits for ADRD, they are rarely asked questions about their own health and well-being (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2020). The development of the COPE was created with a desire to support caregivers who identify as needing social work support before, during, or after a significant other is diagnosed with ADRD. This tool can be rapidly implemented into a medical setting by social workers and mental health professionals or paraprofessionals, it can be completed online or on paper, and it is simple to use and quick to complete.

Limitations and Future Directions

Caregiving is often described as a ‘journey’, ‘career’ or ‘pathway’ because many ADRD caregivers are in their role for 4–20 years (Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2020). However, caregiver interventions are usually time-limited, lasting an average of 4 months (Cheng et al., 2020); counseling sessions also conclude once therapeutic goals are reached. For this reason, the availability of outcome measurements that can be utilized longitudinally and at different points in a caregiver’s journey, including during significant transitions i.e., after diagnosis, hospitalization, patient behavior changes, long-term care placement (Orsulic-Jeras et al., 2020; Whitlatch & Orsulic-Jeras, 2018), is important. Future studies with the COPE would benefit from exploring its utility to capture outcomes at these critical junctures in care across the dementia spectrum.

In addition, we note that more work is needed in larger and more diverse samples to validate and refine the instrument, as well as to explore additional psychometric properties such as divergent and incremental validity relative to other outcome measures. We note the limitations of short forms of the ZBI-4 (Yu et al., 2019), and believe future studies of the COPE relative to a more diverse array of caregiving outcome measures would be beneficial. This is particularly true given the multi-domain nature of the COPE; establishing the psychometric properties of the single item measures versus more detailed constructs and evaluating total score as a marker of outcomes in rigorous, multi-faceted caregiver intervention trials is encouraged. Methods of expanding reliability, particularly by adding more items to subscales focused on caregiving skills or positive aspects of caregiving, as well as focusing more on individualized needs and goals of caregivers scales could be additional areas to expand this measurement set. However, these approaches need to be weighed against the original purpose of the COPE which was to create a brief measure and avoid survey fatigue. Further work and development of this instrument would also benefit from qualitative review of the measures and wording with caregivers, to help maximize understandability and relevance to caregivers. That being said, our hope is that the COPE will help to fill a gap for social work clinicians seeking to incorporate a comprehensive, value-based outcome measure of caregiver counseling needs and goals.

Data Availability

The data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Abma, I. L., Rovers, M., & van der Wees, P. J. (2016). Appraising convergent validity of patient-reported outcome measures in systematic reviews: Constructing hypotheses and interpreting outcomes. BMC Research Notes, 9, 226. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2034-2

Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: THe Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 17(3), 327–406.

Alzheimer’s Association. (2023). Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: the Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13016

Bédard, M., Molloy, D. W., Squire, L., Dubois, S., Lever, J. A., & O’Donnell, M. (2001). The zarit burden interview: a new short version and screening version. The Gerontologist, 41(5), 652–657. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/41.5.652

Borson, S., Boustani, M. A., Buckwalter, K. C., Burgio, L. D., Chodosh, J., Fortinsky, R. H., Gifford, D. R., Gwyther, L. P., Koren, M. J., Lynn, J., Phillips, C., Roherty, M., Ronch, J., Stahl, C., Rodgers, L., Kim, H., Baumgart, M., & Geiger, A. (2016). Report on milestones for care and support under the U.S. national plan to address Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 12, 334–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.01.005

Cheng, S.-T. (2017). Dementia caregiver burden: A research update and critical analysis. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(9), 64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0818-2

Cheng, S.-T., Li, K.-K., Losada, A., Zhang, F., Au, A., Thompson, L. W., & Gallagher-Thompson, D. (2020). The effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for informal dementia caregivers: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 35(1), 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000401

Cho, J., Ory, M. G., & Stevens, A. B. (2016). Socioecological factors and positive aspects of caregiving: findings from the REACH II intervention. Aging & Mental Health, 20(11), 1190–1201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1068739

Collins, R. N., & Kishita, N. (2019). The effectiveness of mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions for informal caregivers of people with dementia: A meta-analysis. The Gerontologist, 59(4), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny024

Gallagher-Thompson, D., Choryan Bilbrey, A., Apesoa-Varano, E. C., Ghatak, R., Kim, K. K., & Cothran, F. (2020). Conceptual framework to guide intervention research across the trajectory of dementia caregiving. The Gerontologist, 60(Suppl 1), S29–S40. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz157

Gaugler, J. E., Bain, L. J., Mitchell, L., Finlay, J., Fazio, S., Jutkowitz, E., Alzheimer’s Association Psychosocial Measurement Workgroup. (2019). Reconsidering frameworks of Alzheimer’s dementia when assessing psychosocial outcomes. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 5(1), 388–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2019.02.008

Gliem, J. A., & Gliem, R. R. (2003). Calculating, interpreting, and reporting cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for likert-type scales. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.iupui.edu/handle/1805/344

Harvath, T. A., Mongoven, J. M., Bidwell, J. T., Cothran, F. A., Sexson, K. E., Mason, D. J., & Buckwalter, K. (2020). Research priorities in family caregiving: Process and outcomes of a conference on family-centered care across the trajectory of serious illness. The Gerontologist, 60(Suppl 1), S5–S13. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz138

Kondrat, M. E. (2013). Person-in-environment. In Encyclopedia of Social Work.

Liu, C., Badana, A. N. S., Burgdorf, J., Fabius, C. D., Roth, D. L., & Haley, W. E. (2021). Systematic review and meta-analysis of racial and ethnic differences in dementia caregivers’ well-being. The Gerontologist, 61(5), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa028

National Association of Social Workers (NASW). (2021). National Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics. https://www.socialworkers.org/about/ethics/code-of-ethics/code-of-ethics-english

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. (2021). Meeting the Challenge of Caring for Persons Living with Dementia and their Care Partners and Caregivers: A Way Forward. The National Academies Press.

Nikzad-Terhune, K., Gaugler, J. E., & Jacobs-Lawson, J. (2019). Dementia caregiving outcomes: The impact of caregiving onset, cognitive impairment and behavioral problems. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 62(5), 543–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2019.1625993

Orsulic-Jeras, S., Whitlatch, C. J., Powers, S. M., & Johnson, J. (2020). A dyadic perspective on assessment in Alzheimer’s dementia: Supporting both care partners across the disease continuum. Alzheimers & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.12037

Pendergrass, A., Becker, C., Hautzinger, M., & Pfeiffer, K. (2015). Dementia caregiver interventions: A systematic review of caregiver outcomes and instruments in randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience, 17(2), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.4172/1522-4821.1000186

Sallim, A. B., Sayampanathan, A., Cuttilan, A., & Chun-Man, H. R. (2015). Prevalence of mental health disorders among caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease. Journal of American Medical Directors Association, 16(12), 1034–1041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.007

Sheikh, J. I., & Yesavage, J. A. (1986). Geriatric depression scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist: THe Journal of Aging and Mental Health, 5(1), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v05n01_09

Whitlatch, C. J., & Orsulic-Jeras, S. (2018). Meeting the informational, educational, and psychosocial support needs of persons living With dementia and their family caregivers. The Gerontologist., 58(Suppl 1), S58–S73. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx162

Yu, J., Yap, P., & Liew, T. M. (2019). The optimal short version of the Zarit Burden Interview for dementia caregivers: Diagnostic utility and externally validated cutoffs. Aging & Mental Health, 23(6), 706–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1450841

Zarit, S. H. (2017). Past is prologue: How to advance caregiver interventions. Aging & Mental Health, 22(6), 717–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1328482

Zhou, Y., O’Hara, A., Ishado, E., Borson, S., & Sadak, T. (2022). Developing a new behavioral framework for dementia care partner resilience: A mixed research synthesis. The Gerontologist, 62(4), e265–e281. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa218

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the entire Comprehensive Memory Center team at UT Health Austin, who are dedicated to providing exceptional care, as well as our social work interns, Kcie Driggers and Martha Santillan-Ibarra. Finally, our deepest gratitude is to the individuals living with dementia and their caregivers. Their input shaped the Comprehensive Memory Center and their stories continue to inspire us to seek excellence in dementia care.

Funding

Our clinic would not be possible without the generous financial support of the The Darrell K Royal Research Fund for Alzheimer’s Disease, James and Miriam Mulva and the Mulva Family Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The requirement for consent was waived by our Institution, IRB approval number 2019110131.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Caregiver Outcomes of Psychotherapy Evaluation Items

Appendix: Caregiver Outcomes of Psychotherapy Evaluation Items

Answer the statements below by marking which option choice you most agree with | ||||

1) I am knowledgeable about dementia (symptoms, stages, behaviors) | ||||

Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

2) I am confident in my caregiving skills | ||||

Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

3) I have communication strategies that are effective with my loved one | ||||

Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

4) I feel able to manage my emotional well-being | ||||

Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

5) I have a network of people who provide me with practical and emotional support | ||||

Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

6) I am equipped to make a decision about keeping my loved one at home or moving to a long-term care community | ||||

Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

7) I enjoy life | ||||

Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

8) I am confident in facing challenges ahead | ||||

Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Aguirre, A., Benge, J.F., Finger, A.H. et al. The Caregiver Outcomes of Psychotherapy Evaluation (COPE): Development of a Social Work Assessment Tool. Clin Soc Work J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-024-00925-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-024-00925-2