Abstract

The purpose of this study is to determine the factors associated with adverse maternal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in urban Fiji. This cross-sectional study used data from existing records of singleton pregnant women with GDM attending the Colonial War Memorial Hospital (CWMH) Suva Fiji between June 2013 and May 2014. Data retrieved included demographic data, antenatal and intrapartum care data, route of delivery, treatment modality, and maternal risk factors. The prevalence of GDM is 3.0%, n = 255/8698, and the most frequent maternal complications were induction of labor (66%), C-section (32%), and preeclampsia (19%), and 25% had babies with birthweight > 4 kg. Older women (≥ 36 years) and those treated with insulin were 5.2 times and 10.7 times, respectively, more likely to have labor induction during childbirth compared with younger women and those on dietary management. Family history of diabetes was associated with 2.4× and/or 2.5× higher odds of cesarean delivery and/or develop hypertension in pregnancy, respectively. Parity > 5 children and diagnoses of GDM after the first trimester reduced the odds of cesarean delivery. The odds of developing preeclampsia in GDM was 3.4 times higher (95% confidence interval (CI) of adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.03, 18.78) among obese women than normal-weight women, and married women were less likely to have babies with birthweight > 4 kg. The prevalence of and adverse outcomes among women with GDM attending antenatal public health care in Suva Fiji were higher than previously reported from the hospital. Older and multiparous women with GDM, those insulin treated, and with a strong family history and high body mass index (BMI) need special attention and better monitoring by health care personnel to reduce adverse outcomes during pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is one of the most common medical pregnancy complications [1,2,3] with estimates of prevalence ranging from 1 to 36% depending on the diagnostic criteria used [3] and steadily increasing [4]. GDM precedes type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in up to one third of women [5] and is associated with an increased risk of obesity and T2DM in the offspring [3, 6]. Adverse health outcomes of GDM repeat across generations [7], and women with GDM are at increased risk for various maternal and fetal complications such as preeclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage, and infection, stillbirth, and large for gestational age infants/macrosomia [3, 8, 9]. The increase in macrosomic infants among GDM women contributes to an increase in operative delivery, especially cesarean section, for various reasons including fetal distress and cephalopelvic disproportion [8, 10, 11].

GDM prevalence is increasing, largely through the obesity pandemic (5), and is now estimated to complicate 1 in 7 pregnancies globally [2]. In Pacific Island nations, numerous reports have highlighted the high prevalence of diabetes [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] and in an earlier work (1994–1998) among Polynesians (including Fijians) in South Auckland, New Zealand. Simmons and colleagues found much higher rates of GDM among Pacific people than Europeans (8.1% vs 3.3%) [12] and much worse birth outcomes with high rates of macrosomia (4.5+ kg birthweight: 18.3% vs 3.4%) and severe neonatal hypoglycemia (< 1.6 mmol/l: 17.3% vs 3.7%) [21].

In Fiji, only two studies [22, 23] have investigated the prevalence of diabetes in pregnancy but none reported the adverse outcomes of GDM. In 1983, Zimmet et al. [22] reported a prevalence of 22.7% among Fijian women of Indian Descent (FID) who were screened using the WHO criteria and in 1990, using O’Sullivan and Mahan’s criteria, another study found a prevalence of 0.6% and 5%, respectively, among ITaukei (indigenous) Fijians and FID women [23]. The study also showed that the prevalence of GDM increased with maternal BMI [23]. At the time of these studies, Fijian women were only screened for GDM during pregnancy only if they had known risk factors including positive family history of diabetes and previous GDM. However, following the landmark “Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO)” study, which reported significant relationship between maternal glycemic levels and pregnancy outcomes [24], the Colonial Memorial War Hospital (CMWH) hospital adopted the modified International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) criteria, which recommended universal screening for GDM for all pregnant women. GDM and diabetes in pregnancy (DIP present if fasting ≥ 7.0 mmol/L and/or 2 h ≥ 11.1 mmol/L) were diagnosed as recommended [25] albeit with slight differences in the testing protocol and diagnostic methods as detailed in our previous paper [26]. Due to changes in the GDM criteria and the recent epidemic of obesity, there is an unmet need to report prevalence and risk factors of maternal outcomes associated with GDM, particularly when we have shown very poor outcomes among neonates of these women [26].

The study aims to investigate the factors associated with adverse maternal outcomes of GDM diagnosed using the modified International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups criteria in an urban Fiji hospital. Data used in this study have been presented in part for neonates of women with GDM [26]. The findings of this study will provide the first high quality evidence on the adverse maternal outcomes of GDM in Fiji.

Materials and Methods

Setting and Study Population

This was a 12-month retrospective cohort study of all women with GDM at the CWMH. The CWMH is the largest and oldest national referral hospital in the urban city of Suva, Fiji [27], and up to 80% of births per annum in the Central Eastern division occur in this hospital [28]. Women with any known risk factor for GDM including age ≥ 30 years, family history of diabetes, past history of GDM, previous macrosomia, and pre-pregnant BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 proceeded to oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) at initial screening. The screening and diagnostic method for GDM in this hospital have been described in detail elsewhere [26] and management of GDM follows the ADIPS guidelines [29] .

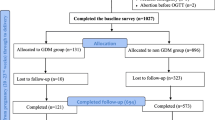

The study group consisted of 267 singleton pregnant women routinely tested for GDM using a two-step process consisting of the 1-h glucose challenge test (GCT) at 24–28 weeks including a non-fasting 50 g glucose load and, if GCT was ≥ 7.8 mmol/l, a 2-h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), and were diagnosed based on the modified IADPSG criteria. Women with multiple pregnancies (n = 6) and preexisting diabetes (n = 2) and those with missing folder (n = 4) were excluded. A total of 255 singleton pregnant women with GDM, who delivered at the hospital within the study time, met the inclusion criteria representing 3.0% of the total number of women (8628). Only data for these women were analyzed.

Ethics and Data Sources

The Declaration of Helsinki was followed throughout the study. Data were obtained from the hospital records of women with GDM who gave birth at CMWH in Suva between June 2013 and May 2014. Data for non-GDM women were not entered in the diabetes registry at the time.

Maternal Outcome Variables

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, maternal trauma, endometritis, and wound infection were the outcomes and were coded as binary, “1” for the presence and “0” for absence. Others included interventions (spontaneous and induction) and mode of delivery (cesarean delivery and normal vaginal delivery including assisted vaginal delivery). Few women had diabetes in pregnancy (DIP), and hence data for GDM and DIP were combined. Individual birthweight was categorized as “1” for baby birthweight > 4 kg and otherwise “0” based on adverse effect of GDM [30]. This study did not further examine other adverse maternal outcomes including endometriosis and wound infection due to their very low occurrence (less than 3%).

Confounding Variables

The choice of potential cofounding factors were based on previous studies [9, 31, 32] and included sociodemographic (age, ethnicity, marital status, parity, level of education); maternal factors such as body mass index (BMI) calculated at the first prenatal visit using WHO criteria: underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), obesity (30–34.9 kg/m2), and morbid obesity ≥ 35 kg/m2 [33], positive family history of diabetes, past history of GDM, baby > 4 kg, stillbirth, and neonatal death (which were simply recorded as present or absent); antenatal factors (gestational age at booking, gestational age of diagnosis, gestational age at delivery); and treatment regimen (diet and insulin). Gestational age at delivery was classified into < 37 weeks and ≥ 37 weeks. In the regression analysis, BMI was further collapsed into three categories, normal, overweight, and obese, due to the low proportion of underweight and morbidly obese women, and levels of education were classified into non-tertiary (no education, primary, secondary) and tertiary (university and polytechnic).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were carried out using STATA/MP version 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). Analysis involved the assessment of frequencies of adverse maternal outcome variables and all confounding variables in the study population. This was followed by univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses, which were used to investigate the association between study variable (maternal demographic and risk factors, antenatal and treatment factors) and each of the key maternal outcomes (preeclampsia, spontaneous delivery, normal vaginal delivery, baby birthweight). All variables were retained in the final model. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios from a logistic model were presented with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Group

Most women (88%) were married, about half (49.4%) were indigenous Fijians (iTaukei), aged 26–35 years, had attained primary or secondary educational qualification, had 2 or more children, and were either obese or morbidly obese with 50% having at least one family member with diabetes (Table 1). More women received diet therapy alone than insulin, with three women receiving either a combination therapy (insulin and metformin, n = 2, 2%) or metformin alone (n = 1, 0.4%).

Prevalence of Adverse Maternal Outcomes of Fijian Women with GDM

Figure 1 presents the distribution of the adverse maternal outcomes of GDM in this study. The most frequent maternal complications were induction of labor (66%), C-section (32%), and 19% developed preeclampsia. In addition, 24.7% had babies with birthweight > 4 kg (the mean birthweight of babies in this study was 3.44 ± 0.05 kg, range, 0.9–5.8 kg). Of the women who had labor induction, 48.5% (n = 82) were performed before the gestational age of 39 weeks and among these group of women, majority (81%) went on to have a C-section. Of the women who did not have labor induction, 18.3% had a C-section (p < 0.0005).

Factors Associated with Adverse Maternal Outcomes of Women with GDM

The unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for factors that were associated with the key outcomes are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Older women (aged 36 years and over) and women receiving insulin were more likely to have elective delivery by induction compared with younger women (aged below 25 years) and those on diet. Women with a past history of GDM were less likely to have delivery by induction compared with those with no past history of GDM (OR 0.27 95%CI: 0.08, 0.96; Table 2), but this effect was nullified after adjusting for potential cofounders (aOR 0.20 95%CI: 0.04, 1.08; Table 3). Women with a previous baby weighing > 4 kg were more likely to have further babies with birthweight > 4 kg (aOR: 5.37, 95%CI: 2.28, 12.66; Table 3), whereas married women were less likely to have babies with birthweight > 4 kg compared with those who were not married (aOR 0.32, 95%CI 0.13, 0.82; Table 3), at the time of this study. Women with a family member with diabetes were more likely to have C-section during childbirth compared with women with no family history of diabetes. Those who had more than five children or were diagnosed with GDM in the second and third trimester had a lower odds of C-section [Table 3]. For women with a past history of stillbirth, the odds of C-section during childbirth was increased by 3 folds compared with the women who had no past history of stillbirth (95%CI of aOR: 0.04, 1.08; p = 0.07) [Table 3].

Fijian women who had a positive family history of diabetes and those who were obese were more likely to develop preeclampsia compared with women with no family member living with diabetes (aOR 2.4, 95%CI 1.21, 4.77; Table 3) and those who had normal weight (aOR 4.4, 95%CI 1.03, 18.78; Table 3). Other factors such as the woman’s age (36 years and over), gestational age at diagnosis, and the maternal risk factors of previous histories of GDM and stillbirth had negligible effects on preeclampsia among women in Fiji [Table 3].

Discussion

This is the first study to explore the adverse outcomes of pregnant women diagnosed with GDM using the modified International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups criteria in Fiji. The study found women with GDM were mostly young, educated, obese, or had 2 or more children and the four key adverse maternal outcomes among these women were C-section, labor induction, preeclampsia, and having a baby with birthweight > 4 kg. Older age (36 years and over), positive family history of diabetes, history of a previous baby weighing > 4 kg, higher maternal BMI, treatment with insulin, and being married were associated with these four key adverse maternal outcomes of GDM. The percentage of obese women with GDM in this study were almost double that for the background population (32%) [35] and reiterates the burden of obesity in the Pacific community [14, 16, 36]. This remains an important public health problem requiring attention particularly due to its rapid increase as shown in the 2011 STEPs Survey, which reported 8.5% increase in obesity prevalence since 2002 [35], and the potential to increase the rate of adverse effects in pregnancies complicated by GDM.

Many of the women (approximately 66%) in this study had adverse maternal outcomes, which was in line with our earlier reports where a similar percentage (60%) experienced poor adverse neonatal outcomes [37]. Lower maternal outcomes including C-section, induction of labor, and instrumental delivery have been reported among Pacific women compared with European women [38]. In that study, obesity was strongly associated with poor neonatal outcomes [37], which is also in agreement with the present study where obese women had higher rates of maternal outcomes particularly preeclampsia compared with women with normal weight. Additionally, higher BMI interacted with other variables to increase the risk of C-section among the women in this study.

Our study also found that ethnicity was associated with birthweight > 4 kg such that babies born to mothers of Indian descent were on average 0.6 kg lighter than babies born to women from other ethnic groups. Ethnicity is an important determinant of maternal outcomes of women with GDM as shown in a review study [4], and in one cohort study that examined 16,157 infants in the UK, the authors found that, after adjusting for maternal and infant factors, Indian and Bangladeshi infants were 0.3–0.4 kg lighter than white infants [39]. In the present study, the association between birthweight and ethnicity was nullified after we adjusted for the cofounders. Of concern was the high proportion of younger women with GDM with 63% under 35 years of age and 49% under 30 years. Since up to 50% of these women may go on to develop type 2 diabetes later in life [40], this is likely to increase the burden of disease in this hospital.

Compared with the background population [41] and two major randomized controlled trials [42, 43], the present study found a higher percentage of labor induction (66% vs 25%, 39%, and 27.3%, respectively) among pregnant women, which was more prevalent among older women receiving insulin treatment. The high rate of labor induction partly reflects the low rate of assisted vaginal deliveries in CMWH (3.1%, 98/255), suggesting the need to strengthen GDM management services in this hospital. A subanalysis conducted among women who had elective delivery by labor induction in this study revealed that majority (81%) of the women that had labor induction performed before 39 weeks gestation ended up having C-section, indicating that the C-section may have been unplanned in these women. According to the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology guideline, the timing of delivery in diet- or exercise-controlled GDM women should not be before 39 weeks of gestation, unless otherwise indicated, and for women with GDM that is well controlled by medications (A2GDM), delivery is recommended from 39 weeks of gestation. Although the report supported earlier delivery for women with poorly controlled GDM, it noted that consideration of timing should incorporate tradeoffs between the risks of prematurity and the ongoing risks of stillbirth [44]. Fijian clinicians may be balancing the risk by performing early delivery to prevent stillbirth; however, there is no clear guidance about the degree of glycemic control that necessitates earlier delivery as well as the recommendations about timing of delivery [45]. Delivery in the late preterm period from 34 weeks to 36 weeks of gestation should also be reserved for those women who fail in-hospital attempts to improve glycemic control or who have abnormal antepartum fetal testing [44]. It is important for clinicians in this hospital to be aware of the high rate of C-section among women with GDM who had labor induction as this was shown to have a negative impact on the mothers’ birth experience and subsequent pregnancies [46]. Discussing the potential benefits and risks of labor induction in GDM with the mothers could help in lowering expectations.

The present study found increased odds of labor induction among Fijian women receiving insulin but no effect on C-section rates when compared with those on nutritional therapy (Table 3). These findings are consistent with Crowther et al’s study, which found lower rate of labor induction (39 vs.29%; aRR 1.36;95%CI 1.15, 1.62) and similar rates of C-section (31 vs 32%, aRR 0.97; 95%, 0.81, 1.16) among women with GDM who received routine care compared with those who received treatment [42]. Although some studies found significant effects of treatment on C-section rates and no effect on labor induction rates [43, 47], they also differ in the direction of the effects. Compared with those on diet, women who received insulin had more C-sections (44.1% vs. 27.0%, p = 0.001) in one study [47], but fewer C-sections (26.9 vs 33.8%, p = 0.02) in the other study [43], after adjustment for confounders. Of the Fijian women receiving nutritional therapy, a significant proportion (40%) required additional insulin to control their diabetes, which may be due to the inclusion of women with DIP (18%) in this study or the fact that Pacific Islanders have greatest need for insulin therapy, and in most cases (65%) medical nutrition therapy failed [48]. The fact that only a few of these women were treated with metformin, which could have lowered the rates of adverse outcomes as well as reduce their reliance on insulin therapy, suggests that clinicians caring for these women were aiming to attain normoglycemia much quicker as the benefits outweigh the risks in GDM [49].

The finding of significant association between marital status and baby’s birthweight > 4 kg in this study is unclear but has previously been attributed to married women having more family support to make positive changes in lifestyle during pregnancy including smoking cessation [50]. This finding needs confirmation from within Fiji and across other cultures.

Strengths and Limitations

There are several strengths of this study including provision of the first quality evidence on adverse maternal outcomes associated with GDM and their associated risk factors, which can be used for development of strategies specific to this community. The study also looked at delivery trends prior to 39 weeks, which provides data for practice improvement. In addition, given that most births in the Central Eastern division occur in CMWH hospital [28], the study has internal validity and may represent the outcomes of women with GDM in the region. The findings also provide baseline data for comparison with future data from the outcomes of the universal screening in Fiji. Despite these strengths, there are some limitations of this study: A) The screening and diagnostic methods used in this study were not fully in line with the current international guidelines for GDM diagnosis particularly the use of GCT and the 2-point OGTT, which will underestimate the prevalence of GDM in this hospital. B) Data were from a single hospital and may not be generalizable to other women attending other hospitals and those without diabetes. C) The study was unable to assess the impact of the adoption of the IADPSG criteria in our setting since such a study would need to compare the outcomes of women pre- and post-implementation of the universal screening for GDM to provide evidence on the cost benefit of the new approach and its impact on the hospital resources. D) Data on pre-pregnancy BMI was not captured making it difficult to ascertain whether the women had unwanted weight gain in gestation.

Conclusions

In summary, the present study showed that Fijian women with GDM attending this public hospital are at high risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes and probably across Fiji. This information is important when caring for Fijian women with GDM particularly during care of older, obese pregnant women who have family history of diabetes or a history of baby weighing > 4 kg and those on insulin therapy and indicate that these women would benefit from targeted lifestyle interventions as well as self or frequent monitoring of blood glucose. The high rate of obesity highlights the need for public health education campaign programs targeting women of childbearing age and during antenatal care on the adverse effects of maternal obesity and to encourage nutritional therapy. More studies are needed in Fiji to confirm these findings particularly in women without diabetes and to guide obstetric clinical practice on these outcomes in pregnancies complicated by GDM.

Availability of Data

Data for this study is stored on the hospital database and can be made available on request from the first author.

References

Ferrara A. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a public health perspective. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Supplement 2):S141–6.

Zhu Y, Zhang C. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and risk of progression to type 2 diabetes: a global perspective. Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16(1):7.

Simmons D. Epidemiology of diabetes in pregnancy. A practical manual of diabetes in pregnancy. 2017:3.

Yuen L, Wong VW, Simmons D. Ethnic disparities in gestational diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(9):68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-018-1040-2.

Cheung NW, Byth K. Population health significance of gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(7):2005–9.

Organization WH. Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy. 2013

Gray SA, Jones CW, Theall KP, Glackin E, Drury SS. Thinking across generations: unique contributions of maternal early life and prenatal stress to infant physiology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(11):922–9.

Simmons D. Diabetes and obesity in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25(1):25–36.

Egan AM, Vellinga A, Harreiter J, Simmons D, Desoye G, Corcoy R, et al. Epidemiology of gestational diabetes mellitus according to IADPSG/WHO 2013 criteria among obese pregnant women in Europe. Diabetologia. 2017;60(10):1913–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-017-4353-9.

Boriboonhirunsarn D, Waiyanikorn R. Emergency cesarean section rate between women with gestational diabetes and normal pregnant women. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;55(1):64–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2015.08.024.

Damm P, Houshmand-Oeregaard A, Kelstrup L, Lauenborg J, Mathiesen ER, Clausen TD. Gestational diabetes mellitus and long-term consequences for mother and offspring: a view from Denmark. Diabetologia. 2016;59(7):1396–9.

Yapa M, Simmons D. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus in a multiethnic population in New Zealand. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;48(3):217–23.

Morgan J. Country in focus: turning the tide of diabetes in Fiji. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(1):15–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70240-2.

Lin S, Tukana I, Linhart C, Morrell S, Taylor R, Vatucawaqa P, et al. Diabetes and obesity trends in Fiji over 30 years. J Diabetes. 2016;8(4):533–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-0407.12326.

Morrell S, Lin S, Tukana I, Linhart C, Taylor R, Vatucawaqa P, et al. Diabetes incidence and projections from prevalence surveys in Fiji. Popul Health Metrics. 2016;14(1):45.

Lin S, Hufanga S, Linhart C, Morrell S, Taylor R, Magliano DJ, et al. Diabetes and obesity trends in Tonga over 40 years. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2016;28(6):475–85.

Joshy G, Simmons D. Epidemiology of diabetes in New Zealand: revisit to a changing landscape. N Z Med J. 2006;119(1235):U1999.

Ekeroma AJ, Craig ED, Stewart AW, Manetll CD, Mitchell EA. Ethnicity and birth outcome: New Zealand trends 1980–2001: part 3, Pregnancy outcomes for Pacific women Australia and New Zealand. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44:541–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2004.00311.x.

WHO. Noncommunicable diseases in the Western Pacific Region: a profile. WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Manila, Philippines. 2012

Tin STW, Lee CMY, Colagiuri R. A profile of diabetes in Pacific Island countries and territories. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;107(2):233–46.

Simmons D, Thompson CF, Conroy C. Incidence and risk factors for neonatal hypoglycaemia among women with gestational diabetes mellitus in South Auckland. Diabet Med. 2000;17(12):830–4.

Zimmet P, Taylor R, Ram P, King H, Sloman G, Raper LR, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in the biracial (Melanesian and Indian) population of Fiji: a rural-urban comparison. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;118(5):673–88.

Gyaneshwar R, Ram P. The prevalence of gestational diabetes in Fiji. Fiji Med J. 1990;16:40.

Group HSCR. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1991–2002.

International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):676–82.

Fuka F, Osuagwu UL, Agho K, Gyaneshwar R, Naidu S, Fong J, et al. Factors associated with macrosomia, hypoglycaemia and low Apgar score among Fijian women with gestational diabetes mellitus. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–14.

Organization WH. The Fiji Islands health system review. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2011.

Bythell M, Nand D, Tikoduadua L, Vereti I, Kado J, Fong J, et al. Stillbirths, neonatal and infant mortality in Fiji 2012: preliminary findings of a review of medical cause of death certificates. Ministry of Health and Medical Services: Fiji Journal of Public Health; 2016.

Hoffman L, Nolan C, Wilson JD, Oats JJ, Simmons D. Gestational diabetes mellitus--management guidelines. The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society. Med J Aust. 1998;169(2):93–7.

Yamamoto JM, Kellett JE, Balsells M, Garcia-Patterson A, Hadar E, Sola I, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus and diet: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials examining the impact of modified dietary interventions on maternal glucose control and neonatal birth weight. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(7):1346–61. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-0102.

King H. Epidemiology of glucose intolerance and gestational diabetes in women of childbearing age. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(Suppl 2):B9–13.

Simmons D. Relationship between maternal glycaemia and birth weight in glucose-tolerant women from different ethnic groups in New Zealand. Diabet Med. 2007;24(3):240–4.

Organization WH. The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. Sydney: Health Communications Australia; 2000.

FBoS. Fiji statistics at a glance. Suva: Fiji Bureau of Statistics; 2017.

Snowdon W, Tukana I. Fiji-NCD Risk Factors STEPS REPORT 2011. Suva: Ministry of Health and Medical Services; 2011.

Lin S, Naseri T, Linhart C, Morrell S, Taylor R, McGarvey ST, et al. Trends in diabetes and obesity in Samoa over 35 years, 1978–2013. Diabet Med. 2016;34(5):654–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13197.

Fuka F, Osuagwu UL, Agho K, Gyaneshwar R, Naidu S, Fong J, et al. Factors associated with macrosomia, hypoglycaemia and low Apgar score among Fijian women with gestational diabetes mellitus. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-2821-6.

Sadler L, McCowan L, Stone P. Associations between ethnicity and obstetric intervention in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2002;115(1148):86.

Kelly Y, Panico L, Bartley M, Marmot M, Nazroo J, Sacker A. Why does birthweight vary among ethnic groups in the UK? Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. J Public Health. 2008;31(1):131–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdn057.

Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9677):1773–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60731-5.

Berger H, Melamed N. Timing of delivery in women with diabetes in pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2014;7(1):8–16.

Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jeffries WS, Robinson JS. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2477–86.

Landon MB, Spong CY, Thom E, Carpenter MW, Ramin SM, Casey B, et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of treatment for mild gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1339–48.

Caughey AB. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(2):e49–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002501.

Caughey AB, Valent AM. When to deliver women with diabetes in pregnancy? Am J Perinatol. 2016;33(13):1250–4.

Hildingsson I, KarlstrÖm A, Nystedt A. Women’s experiences of induction of labour–findings from a Swedish regional study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51(2):151–7.

Benhalima K, Robyns K, Van Crombrugge P, Deprez N, Seynhave B, Devlieger R, et al. Differences in pregnancy outcomes and characteristics between insulin- and diet-treated women with gestational diabetes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:271. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0706-x.

Yuen L, Wong VW. Gestational diabetes mellitus: challenges for different ethnic groups. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(8):1024–32.

Gamson K, Chia S, Jovanovic L. The safety and efficacy of insulin analogs in pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;15(1):26–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767050310001650680.

Kane JB. Marriage advantages in perinatal health: evidence of marriage selection or marriage protection? J Marriage Fam. 2016;78(1):212–29.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the following persons for their help during data collection: James Fong, Nola Mahe, Ilisapeci Kubuabola, Drs Julia Singh, Amanda Noovao, Pushpa Nusair, Litia Narube, Swaran Naidu, Dr. Viliame Nasila, Dr. Vasiti Cati, and Professor Rajat Gyaneshwar.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

UL Osuagwu: Protocol/project development, data management, data analysis, manuscript writing

F Falahola: Protocol/project development, data collection or management

A Khan: Protocol/project development, manuscript writing

K Agho: Data analysis, manuscript writing/editing

D Simmons: Protocol/project development, manuscript editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

I certify on behalf of myself and all co-authors that all authors have read and approved the manuscript, and there are no financial disclosures or conflict of interest of any sort. The protocol for the research conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki in 1995 (as revised in Edinburgh 2000) and was approved by Research Ethics Committee of the College of Medical Nursing and Health Sciences of the Fiji National University and by the Fiji National Health Research Ethics Review Committees (ref #: 2015.48.CEN).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Consent

The submitted work is an original retrospective study and not under consideration for publication in any other journal.

Code Availability

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Osuagwu, U.L., Fuka, F., Agho, K. et al. Adverse Maternal Outcomes of Fijian Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and the Associated Risk Factors. Reprod. Sci. 27, 2029–2037 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-020-00222-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-020-00222-6