Abstract

Purpose

Inguinal hernia is one of the most common condition requiring surgical repair in childhood. The recurrence rate is between 1 and 2%. Open repair of recurrent inguinal hernia may be challenging due to the difficulty in dissection of hernia sac from spermatic cord and testicular vessels. On the other hand, laparoscopic approach offers an easier and safer repair without engaging these structures. The aim of this study is to present the experience in laparoscopic repair of recurrent inguinal hernias in children.

Methods

The children who underwent laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair between 2015 and 2021 for recurrence after a previous open hernia repair were included in this study. Laparoscopic percutaneous internal ring suturing was performed in all these patients.

Results

A total of 24 children (2 girls and 22 boys) were enrolled for analysis. The mean age was 15 months and the mean weight was 21 kg. Fourteen children had right hernia, while 10 had left. Two of patients had a second open surgery for a recurrent hernia. Of the 24 recurrences, 17 developed in the first year following surgery and seven later. No complication was encountered after laparoscopic repair and no recurrence after a mean follow-up of 24.6 months.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic-assisted percutaneous internal ring suturing method may be preferred in children with recurrent inguinal hernias who underwent previous open repair in order to avoid possible injury to the cord due to the scars of primary operation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inguinal hernia (IH) recurrence after treatment is uncommon among children. The rates of recurrence range from 0.5 to 4% [1]. However, due to the huge numbers of IH repairs, pediatric surgeons are accustomed to the recurrence. Not so long ago, open repair (OR) was the only option, but in the late 1990s, laparoscopic procedures began to gain popularity [2, 3]. Surgeons have always found it challenging to perform the OR for recurrent IH, especially in boys. The main causes that offer challenges in redo surgery are fibrotic changes in the inguinal canal and displaced anatomical structures.

The most serious complication of this procedure is testicular atrophy, which has been linked to redo surgery in this region. During the dissection of the fibrotic inguinal canal, the testicular arteries and vas deferens may easily be injured. Microtrauma to these structures may be inevitable, even if the surgeon properly conducts the dissection.

The percutaneous internal ring suturing (PIRS) technique, on the other hand, might be a secure and workable option for recurrent IH repair in children who have already had OR. The benefit of a laparoscopic extraperitoneal operation is avoiding spermatic structures and associated fibrotic alterations.

Material and methods

The Declaration of Helsinki was followed for the study. Legal guardians of each child submitted written informed permission, and the Ethical Committee approval was obtained.

The study included 24 children with recurrent IH after undergoing OR and subsequently treated with the PIRS technique between 2015 and 2021. Children who had undergone first laparoscopic repairs for hernias were not enrolled in this study. All children underwent laparoscopic PIRS as the recurrence repair technique. Retrospectively reviewing the patient charts allowed for the analysis of demographic information, recurrences, intraoperative and postoperative complications, and documentation of other intraoperative observations.

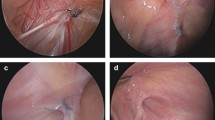

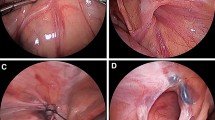

We performed the surgeries with the PIRS technique as reported by Patkowski et al. [4]. For the procedure, a 4 mm umbilical port was inserted while the patient was placed in the supine position. Depending on the patient’s weight and age, the intraabdominal CO2 pressure was set between 6 and 12 mm Hg. To enter the preperitoneal area, an 18–22 gauge angiocath needle was employed. To create a loop for ligation, a non-absorbable suture was passed into the needle. The first location was often the lateral-superior corner of the inguinal ring, and the first half-round was made by dissecting the peritoneum and encircling the internal ring. The second suture was then inserted into the peritoneal cavity once the loop had been pushed into the cavity, beginning at the same location and moving counterclockwise around the internal ring where the first suture approximated it. The needle was captured in the other loop before inserting the suture into the cavity. The first loop was then used to press and draw the suture out. A polyfilament braided suture was used to replace the previous one. It was double-knotted while encircling the internal ring, leaving the knot in the extraperitoneal space beneath the skin. After the PIRS operation, scrotal fluid was extracted with a 24 gauge needle in case of hydrocele.

For the statistical analysis: The Student's t-test was used when normally distributed variables were compared. Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the non-normally distributed variables. Pearson's Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables between the two groups. Values were judged significant at a p-value of 0.05.

Results

A total of 24 children were operated on for hernia recurrence and all previously underwent open repair (median: 34 months). Thirteen (54%) were operated between 2010 and 2015 while 11 (46%) after 2015. The ages of the children were between 3 months and 17 years, the median weight was 16 kgs (4.5–56 kgs). There were two girls and 22 boys. Fourteen children had right hernias, while 10 had left. Two of these patients had undergone a second repair for recurrence. Of the 24 recurrences, 17 developed in the first year following surgery, and seven occurred later. Table 1 illustrates the detailed presentation of the patient demographics.

On review of the previous surgical charts, high ligation hernia repair with absorbable sutures was confirmed in all of the children. After dissection, a high ligation was performed using one stitch from the bottom of the sac and one knot without a stitch beneath it to avoid entangling the spermatic cord and blood vessels in boys. Hernia sacs were removed in all of the children. Additionally, seven of the boys had co-existing hydrocele at the initial presentation for inguinal hernia. A hydrocele or hematoma developed following the initial open repair in 2 patients each, respectively.

During the laparoscopic procedure, no intraoperative adhesions or secondary findings related to the initial procedure were found in any patient. There were no complications during the procedure and no extraordinary findings (femoral or direct hernia) were observed in any patients. In two children, needle aspiration of a hydrocele was performed following PIRS repair.

During the postoperative follow-up, no recurrence was observed after laparoscopic PIRS repair. There were no postoperative complications like hydrocele or hematoma. A granuloma at the inguinal incision developed in one child in the early postoperative period, but it was managed by local care and resolved without further issues. The average duration of follow-up was 24.6 (8–44) months.

Discussion

Although the open method is still preferred for IH repair, laparoscopic methods are becoming more common. There have been few studies on laparoscopic repair of recurrent inguinal hernias in children [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The current study suggests that laparoscopic PIRS repair can be carried out safely in recurrent IH repair. Among the 24 children who underwent surgery for recurrent IH, none experienced recurrence or any type of complication.

One of the important factors in patient selection for PIRS of recurrent IH is the patient's body weight. For example, when we evaluated the 17-year-old female patient, we thought that she was suitable for the PIRS method due to her low body weight. The length of the needle we used was enough to pass the inguinal ring. We did not need an alternative method as the ring closed easily.

One of the major causes of recurrence was the failure to remove the hernia sac during laparoscopic surgery [5]. However, this was not the condition in our 24 patients with recurrence as all had undergone open surgery and sacs were removed. Prematurity, overweight, connective tissue diseases, inability to completely remove the sac or ruptured hernia sac, delay of fibrosis and use of absorbable sutures were cited as reasons for IH recurrence in children after open surgery [7,8,9,10].

When PIRS method was first described, there were debates about recurrence rates, but today the rates are comparable to intraperitoneal and open repairs. In the current literature, this range is 2–4% in the PIRS method and 0.5–4% in OR. [7, 11, 15, 18]. As a result, it appears reasonable to select the least invasive method with the least risk of increased recurrence and complications.

Recurrent IH management via the PIRS method appears to be beneficial in children who have had open or laparoscopic repair. When considering previous OR, the primary pitfall of secondary repair may be that fibrosis and adhesions in the inguinal canal after a previous open procedure is common, so laparoscopic repair appears to be much safer in terms of potential damage to spermatic vessels and the vas deferens comparing to OR of recurrent disease. Furthermore, laparoscopic repair has many advantages, including the ability to explore the contralateral inguinal ring, a lower risk of injury to obliterated organs, cosmetic benefits, and a shorter operation time [8, 9, 11,12,13]. Some authors claimed that distinguishing the vas deferens in OR of recurrent hernias in secondary cases may be difficult if they were also performed open previously [14, 15]. This also lengthens the operation time [15]. In terms of the similar operation times of open and laparoscopic IH repairs for primary cases, it should be noted that secondary OR would be much longer, but secondary laparoscopic repairs would be comparable to primary repairs. Laparoscopic repair can be done either extraperitoneally or intraperitoneally [7, 16]. Although some authors recommend an intraperitoneal approach with hernia sac disconnection and muscular repairs in recurrent disease, others claim that the extraperitoneal PIRS method is sufficient for avoiding recurrence and may be preferred because it is less invasive and simpler [5, 7, 12, 14, 17]. Our mid-term results with a mean of 24 months of follow-up demonstrated no testicular atrophy. In addition, we believe that the PIRS method is adequate for recurrent IH repair in children too.

A laparoscopic view of the inguinal canal may also reveal contralateral PPV, lipoma, and other abnormalities [14, 19]. Excluding such conditions may also reduce complications and recurrences later on. Minimal PPV in open surgery is sometimes overlooked and justifies reoperation [15, 20]. Another advantage of laparoscopy is that it exposes other rare conditions such as direct or femoral hernias [21]. Because recurrence after inguinal hernia repair is uncommon, these findings should be kept in mind in the event of a recurrence. These rare situations may be easily overlooked, especially if the previous operation was performed openly. All of the cases in this study were true recurrences, and we had not seen these rare findings in any operations.

The small number of patients with an acceptable follow-up period is a limitation of this study. The study could also be strengthened further by comparing the OR of recurrent inguinal hernia to laparoscopic repair.

Conclusion

The laparoscopic-assisted PIRS method may be beneficial in children with recurrent IH who have previously undergone open inguinal hernia repair. As a result, potential harm to the cord and vessels caused by the adhesions or scar tissue related to the primary operation may be avoided.

References

Pogorelić Z, Rikalo M, Jukić M et al (2017) Modified marcy repair for indirect inguinal hernia in children: a 24-year single-center experience of 6826 pediatric patients. Surg Today 47:108–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-016-1352-2

Amin El-Gohary M (1997) Hernia in Girls. Pediatr Endosurg Innov Tech 1:185–188

Treef W, Schier F (2009) Characteristics of laparoscopic inguinal hernia recurrences. Pediatr Surg Int 25:149–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-008-2305-7

Patkowski D, Czernik J, Chrzan R et al (2006) Percutaneous internal ring suturing: a simple minimally invasive technique for inguinal hernia repair in children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 16:513–517. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2006.16.513

Lee SR, Park PJ (2019) Laparoscopic reoperation for pediatric recurrent inguinal hernia after previous laparoscopic repair. Hernia 23:663–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1840-y

Montupet P, Esposito C (1999) Laparoscopic treatment of congenital inguinal hernia in children. J Pediatr Surg 34:420–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3468(99)90490-6

Zhu H, Li J, Peng X et al (2019) Laparoscopic percutaneous extraperitoneal closure of the internal ring in pediatric recurrent inguinal hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 29:1297–1301. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2019.0119

Xiang B, Jin S, Zhong L et al (2015) Reasons for recurrence after the laparoscopic repair of indirect inguinal hernia in children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 25:681–683

Miyake H, Fukumoto K, Yamoto M et al (2017) Risk factors for recurrence and contralateral inguinal hernia after laparoscopic percutaneous extraperitoneal closure for pediatric inguinal hernia. J Pediatr Surg 52:317–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.11.029

Grosfeld JL, Minnick K, Shedd F et al (1991) Inguinal hernia in children: factors affecting recurrence in 62 cases. J Pediatr Surg 26:283–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3468(91)90503-L

Gause CD, Casamassima MGS, Yang J et al (2017) Laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair in children ≤3: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Surg Int 33:367–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-016-4029-4

Patkowski D, Chrzan R, Jaworski W et al (2006) Percutaneous internal ring suturing for inguinal hernia repair in children under three months of age. Adv Clin Exp Med 15:851–856

Lee SR (2018) Efficacy of laparoscopic herniorrhaphy for treating incarcerated pediatric inguinal hernia. Hernia 22:671–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1655-2

Chan IHY, Tam PKH (2017) Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in infants and children: state-of-the-art technique. Eur J Pediatr Surg 27:465–471. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1608685

Yildiz A, Çelebi S, Akin M et al (2012) Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy: a better approach for recurrent hernia in boys? Pediatr Surg Int 28:449–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-012-3078-6

Shalaby R, Ismail M, Dorgham A et al (2010) Laparoscopic hernia repair in infancy and childhood: evaluation of 2 different techniques. J Pediatr Surg 45:2210–2216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.07.004

Shehata SM, Elbatarny AM, Attia MA et al (2015) Laparoscopic interrupted muscular arch repair in recurrent unilateral inguinal hernia among children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 25:675–680. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2014.0305

Koivusalo AL, Korpela R, Wirtavuori K et al (2009) A single-blinded, randomized comparison of laparoscopic versus open hernia repair in children. Pediatrics 123:332–337. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3752

Wolak PK, Patkowski D (2014) Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in children using the percutaneous internal ring suturing technique–Own experience. Wideochirurgia I Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 9:53–58. https://doi.org/10.5114/wiitm.2014.40389

Schier F (2007) The laparoscopic spectrum of inguinal hernias and their recurrences. Pediatr Surg Int 23:1209–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-007-2018-3

Moirangthem GS, Singh CA, Panme H (2010) Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in children. J Med Soc 24:103–107

Funding

No funding was received for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There was no Conflicts of interest among authors.

Ethical declaration

All patients were managed as per the Helsinki declaration as well as approval from the local Ethics committee.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ergun, E., Khalilova, P. & Yagiz, B. Laparoscopic recurrent inguinal hernia repair in children who underwent open procedure. J Ped Endosc Surg 4, 157–160 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42804-022-00157-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42804-022-00157-6