Abstract

Uttl (this issue) argues that scores from Student Evaluations of Teaching (SET) must not be used for making high-stakes career decisions because they are not predictive of effective teaching or of teacher effectiveness. I note in this article that teaching effectiveness can be operationalized with reference to outcomes like student test performance, with reference to processes like student engagement and motivation, or with reference to personal experiences like student satisfaction with courses and teachers. I argue that the latter of these alternatives is prioritized in today’s higher education marketplace, and this explains developments like grade inflation and course workload deflation because both are effective in elevating student satisfaction rating. By contrast to Uttl, I argue that as indicators of students’ satisfaction with courses and teachers, SET scores are valid and their use for career decision-making is understandable and defensible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Uttl’s article “Student Evaluation of Teaching (SET): Why the Emperor has no clothes and what we should do about it?” is a critical, comprehensive, and impassioned summary of and commentary on research pertaining to students’ evaluation of teaching, as well as an important reminder of the ethical, legal obligation for professionals to use valid and reliable measurements for making high-stakes career decisions. Uttl notes that SET are used both for formative purposes (e.g., making improvements in course content or organization or in teaching practices) and for summative purposes (e.g., making staff contract and promotion decisions). The substance of his article is on the latter and documents in a compelling manner that SET scores are confounded by a myriad of factors (e.g., the course subject matter; whether a course is required or not required; instructor “hotness”), thus leading to the conclusion that “the emperor has no clothes”—that SET scores are specious and thus must not be used for any summative purposes.

Uttl’s article raises puzzling questions like these: Why are SET scores still widely used today for summative purposes, despite the unrefuted growing evidence that SET scores are hopelessly flawed and not predictive of a teacher’s contribution to students’ learning? Are the educational institutions that use SET scores for making high-stakes career decisions ignorant of the myriad confounds inherent in SET scores and are they blatantly flaunting the professional ethical obligation to use measurements that are valid and reliable (AERA, APA, & NCME, 2014; American Psychological Association, 2017; Canadian Psychological Association, 2017)?

In the paragraphs that follow, I argue that such puzzling questions occur only with some operationalizations of teacher effectiveness, and most are not directly pertinent or prioritized in today’s higher education services marketplace. Uttl raises this possibility by acknowledging that “it has been widely argued that SET are nothing but measures of students’ satisfaction.” Student satisfaction with teaching may not be particularly palatable as a definition of teaching effectiveness, but it is a permissible operationalization of the construct. Moreover, just as other sellers of products and services (e.g., Amazon, Alibaba, Starbucks) use surveys to track their customers’ satisfaction, it makes sense for educational institutions to do the same in the interest of customer retention and to signal that they care about their students’ subjective experience of higher education.

The puzzle raised by Uttl’s article does not occur if teaching effectiveness is operationalized as a specific outcome, as measuring a teacher’s impact—by virtue of their teaching practices, course content and organization, use of classroom resources, etc.—on their students’ performance on a standardized test (Campbell et al., 2004). Obviously, today, this is not the purpose for administering SET, first, because education institutions are not using standardized tests for measuring students’ course knowledge and skills, and second, because if education institutions measured their students’ performance on standardized tests, they would not need SET scores—students’ subjective ratings—for gauging teacher effectiveness. After all, if consistently and repeatedly a higher proportion of the students pass criterion on a standardized test when taught by Instructor A than by B, Instructor A is objectively a more effective teacher.

Education institutions are probably aware of the subjectivity of SET scores and also aware that it is possible to develop standardized, valid, and reliable tests of the knowledge and skills related to the courses they offer. From the fact that they are not using such tests, I infer that measuring and documenting students’ course-related achievements are not a critical component of their education mission today.

Personal experience corroborates this inference. In my 35-year career, not a single faculty meeting focused on setting course-specific knowledge and skill requirements or on how to measure them objectively. During the same period, my university created criterion-referenced standardized tests for professors related to privacy and confidentiality; to data handling, storage, and security; and to bullying. Consistent with such efforts, I still have hope that higher education institutions may one day also require standardized tests for weighing students’ course achievements. By taking this step, education institutions would become better aligned with society’s use of standardized knowledge and skills tests for assessing, for example, fitness to drive on public roads, competency to provide lifesaving first aid at work, and safe and responsible babysitting at home, as well as for licensing professionals like psychologists, nurses, pilots, teachers, and engineers.

The question why are invalid SET scores still used today for summative purposes? is directly germane to an alternate, broader conception of effective teaching which considers it a process that is aligned with students and their learning needs (Devlin & Samarawickrema, 2010; Qureshi & Ullah, 2014) and recognizes that effective teachers influence students in multiple ways not directly indexed by test scores, for example, by inspiring them and fostering their motivation and curiosity and confidence in their knowledge and skills (Atkins & Brown, 2002). Consistent with this definition, it would be reasonable to survey students for the purpose of gathering information about teaching effectiveness. However, constructs such as student motivation, curiosity, and confidence in knowledge and skills are very complex and thus difficult to measure in a valid and reliable manner. Such constructs are likely to be measurable with a fair degree of validity and reliability, as suggested, for example, by valid and reliable surveys available today for assessing employee motivation (Gagné et al., 2010) or career commitment (Allen & Meyer, 1990). However, as noted by Uttl, the surveys used for SET today have not undergone any kind of development process to ensure their validity and reliability, and therefore, they are not in the same quality group as employee motivation or career commitment surveys, or surveys used in clinical practice or for counseling. Moreover, surveys of constructs like employee motivation yield valid measurements only when they are administered under standardized conditions, but nothing is standardized about SET; students may complete the SET survey individually in a quiet classroom or as a group at a pub crawl. Finally, SET samples tend to be small (~ 40% of students typically complete SET surveys; Diane et al., 2017), and respondents are always self-selected and not representative. As a consequence, and considering the myriad indictments of SET in Uttl’s article, I do not believe that today’s education institutions esteem SET scores as valid and reliable measures of teaching effectiveness defined as responsiveness to student needs and fostering motivation and curiosity and building confidence in knowledge and skills.

Uttl’s article documents the massive expansion of the higher education marketplace in the past eight decades and the commensurate profound changes in the student population, and in my view, they provide a fully satisfactory explanation of the contemporary use of SET scores for summative purposes. Based on 2022 US census data, Uttl notes that the population of adults between 25 and 34 years of age with at least a 3-year college degree has gone from 13% in 1940 to 67% in 2022. He also notes that in order to achieve this high degree of market penetration, education institutions have lowered admission standards, bringing about a decline in students IQ scores from an average of about 120 in 1940 to an average of about 100 today. These facts suggest that today’s higher education institutions may have exhausted the market of education customers and that customer retention has become of strategic importance to their business mission. Education institutions likely are aware that “the well-satisfied customer will bring the repeat sale that counts” (attributed to J. C. Penney), and thus, I believe they use SET scores for the purpose of tracking customer satisfaction.

A highly desirable attribute of SET scores as ratings of student satisfaction with courses and teachers is that they are valid, in the sense of not doubtable as indicators of personal experience. As documented in Uttl’s article, SET scores may be influenced by factors related to students (e.g., ageism, genderism, racism), factors related to teachers (e.g., teacher is old, lacks “hotness”), and factors related to courses (e.g., course is required and difficult). However, if we regard SET scores as satisfaction ratings, Uttl’s factors are no longer worrisome confounds; they are merely a portion of many influences of students’ experience. If students give low satisfaction ratings for a required calculus course taught by an old white male instructor, it does not matter if the low ratings are due to the fact that students do not like required or mathematics course or old white instructors. In the marketplace where the customer is always right and provided the data sample is large enough, customer satisfaction ratings are taken at face value, and they inform decision-making.

To the extent that SET scores are used for high-stakes decision-making by education institutions today, this practice is consistent with how customer satisfaction ratings are used elsewhere, for example, for employee recognition programs by coffee shops, pharmacies, banks, and insurance companies (Luthans, 2000). Famously, customer ratings are used also for selecting the on-air talent for news programs and media shows, that is, for finding individuals with the look, voice, and personality that is able to engage and keep an audience. Why should not today’s education institutions use ratings for tailoring their on-air talent, for example, by rewarding teachers who consistently and repeatedly receive high student satisfaction ratings?

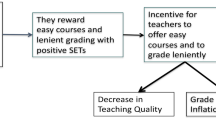

Uttl’s article documents several developments in higher education which seem intended mainly to boost student satisfaction ratings. Perhaps, the most obvious is the substantial degree of grade inflation in recent decades. Giving higher grades to students is guaranteed to increase SET scores just as does giving them candy or chocolates. In tandem with grade inflation, Uttl also documents the occurrence of substantial course workload deflation across the decades, and this development also is likely intended boost student satisfaction ratings. Also worth noting is a more recent, different kind of effort by many education institutions which may earn higher satisfaction ratings from student, specifically the implementation of sweeping equity, diversity, and inclusiveness programs.

To conclude this commentary, I note that as a course instructor, I often fretted about SET scores until I classified them as mere customer satisfaction ratings, and then I fretted more about not having a valid and reliable tool for measuring what I believed to be the purpose of higher education: providing opportunities for acquiring and refining knowledge, skills, insights, and intuitions. Evidently, Uttl is also fretting about this latter issue. In contrast to Uttl, however, I believe that using SET scores as student satisfaction ratings is understandable, acceptable, and probably useful in today’s higher education marketplace. Today’s education customers seem to want subjective ratings for making decisions about products (e.g., books, phones, cars) and services (e.g., banking, food delivery, TED talks) and also about higher education courses and teachers. Despite this status quo, and in view of the substantial costs of higher education and the waning value of many college and university degrees (“Useless studies,” 2023), I am convinced—at least hopeful—that one day higher education students will demand different information about courses and teachers and that they will insist on valid and reliable data that show which courses and teachers do versus do not deliver enhanced performance on standardized criterion-referenced tests.

References

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education. (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. American Educational Research Association.

American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychological Association.

Atkins, M., & Brown, G. (2002). Effective teaching in higher education. Routledge.

Campbell, R. J., Kyriakides, L., Muijs, R. D., & Robinson, W. (2004). Differential teacher effectiveness: Towards a model for research and teacher appraisal. Oxford Review of Education, 29, 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980307440

Canadian Psychological Association. (2017). Canadian code of ethics for psychologists fourth edition. Canadian Psychological Association.

Devlin, M., & Samarawickrema, G. (2010). The criteria of effective teaching in a changing higher education context. Higher Education Research & Development, 29, 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903244398

Diane, D., Chapman, D. D., & Joines, J. A. (2017). Strategies for increasing response rates for online end-of-course evaluations. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 29, 47–60.

Gagné, M., Forest, J., Gilbert, M.-H., Aube, C., Morin, E., & Malorni, A. (2010). The motivation at work scale: Validation evidence in two languages. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70, 628–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164409355698

Luthans, K. (2000). Recognition: A powerful, but often overlooked, leadership tool to improve employee performance. Journal of Leadership Studies, 7, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190000700104

Qureshi, S., & Ullah, R. (2014). Learning experiences of higher education students: Approaches to learning as measures of quality of learning outcomes. Bulletin of Education and Research, 36, 79–100. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Learning-Experiences-of-Higher-Education-Students%3A-Qureshi-Ullah/901e743718cd6193fe5c2fcde4b30c810fe6cedf#citing-papers

Useless studies: Was your degree really worth it? (2023, April 8). The Economist.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I researched and wrote all parts of this submission

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Graf, P. Making Sense of Today’s Use of Student Evaluations of Teaching (SET). Hu Arenas 7, 446–450 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-023-00377-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-023-00377-z