Key summary points

To analyze the associations between pain and physical performance in different aging contexts.

AbstractSection FindingsLower limbs Pain or Back Pain were associated with poor physical performance in older people.

AbstractSection MessagePain symptoms are associated with reduced physical performance in older people, even with interference from clinical and sociodemographic factors.

Abstract

Purpose

To analyze the associations between pain and physical performance in different aging contexts.

Methods

Data from 1725 older adults from Canada, Brazil, Colombia, and Albania from the 2014 wave of the IMIAS were used to assess the associations between Back Pain (BP) or Lower Limb Pain (LLP) and physical performance by the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). Three binary logistic regression models adjusted for sex, age, study site, education, income sufficiency, BMI, depressive symptoms, and chronic conditions were used to estimate the associations between LLP or BP and SPPB. The SPPB was classified into good performance (8 points or more) and poor physical performance (< 8 points).

Results

The mean age of the older men was 71.2 (± 3.0) and the mean age of the women was 71.2 (± 2.8) years. Older men (72.8%, p < 0.05) and women (86.1%, p-value < 0.05) from Albania had the highest frequencies of self-reported general pain. Older women in Colombia had the highest frequencies of LLP or BP (33.5%, p-value < 0.05). In the fully adjusted logistic regression model, LLP or BP was significantly associated with poor SPPB (OR = 0.48, 0.35 to 0.66 95% CI, p < 0.01).

Conclusions

Pain symptoms are associated with reduced physical performance in older people, even when adjusted for other clinical and sociodemographic factors. Protocols for aiming to increase the level of physical activity to manage pain should be incorporated into health care strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pain is a multifactorial phenomenon influenced by physical, emotional, sociocultural, and environmental aspects, defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience described in terms of actual or potential tissue injuries related to previous experiences [1]. Around one in three older people reports persistent pain [2], and the existence of pain in this population may be associated with depressive symptoms, social isolation, changes in family dynamics, and hopelessness [3]. Pain is also among the 10 main causes of disability in the world, which has an important impact on functional and socioeconomic activities in developed and developing countries [4].

Another relevant aspect of aging is physical performance, an important predictor of health in the older population due to its ability to identify adverse outcomes, as it detects losses in functional capacity, hospitalization, institutionalization, and mortality [5]. Among the tools for assessing the physical performance of older people, the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) is a widely used test that analyzes balance, walking speed, and lower limb strength [6]. The associations between pain and physical performance in older people have been investigated in certain studies, where the main results show that pain reduces physical performance and can mediate adverse effects on this component of functionality [7, 8]. In a recent study evaluating 133 older people living in long-stay institutions in Brazil, it was identified that older people who reported pain symptoms had moderate or poor physical performance, measured by the SPPB [9].

The above-mentioned information becomes more relevant when we consider that by the year 2050, 80% of older people will live in low- and middle-income countries [10] and may face many challenges that can contribute to increased pain symptoms and reduced physical performance. Low-income older adults may have less access to resources that can help manage pain and improve physical performance, such as physical therapy, exercise programs, and assistive devices. They also may experience social isolation and lack of social support, which can lead to increased feelings of depression and anxiety, and these factors can exacerbate the negative effects of pain on physical performance [11].

Overall, there are several epidemiologic contexts that can affect the relationship between pain symptoms and physical performance in aging populations. We hypothesize that older adults living in low-income communities may have a higher burden of pain and reduced physical performance due to economic and sociocultural differences. The International Mobility in Aging Study [12] offers an important opportunity to assess how the presence of painful symptoms can affect functional performance in older individuals in four countries (Canada, Albania, Colombia and Brazil). For this study, our objective is to analyze the associations between pain symptoms and physical performance in different epidemiologic contexts of aging.

Methods

Research characterization

IMIAS is a multicenter, multidisciplinary, population-based longitudinal study conducted in Saint-Hyacinthe and Kingston (Canada), Tirana (Albania), Manizales (Colombia), and Natal (Brazil). These sites have different socioeconomic, political, cultural, and religious contexts, which contribute to the formation of different population aging processes at each site. The IMIAS evaluated 400 participants (200 men and 200 women) in each city, with ages ranging from 65 to 74 years old. Samples were collected at baseline (2012) and two more years of follow-up (2014 and 2016). For this study, we analyzed the data from the 2014 IMIAS follow-up wave.

Recruitment

Volunteers were recruited through registration at primary care centers in the neighborhoods of Manizales and Natal. A random sample was drawn and the researchers contacted them and invited them to participate in the study. In Kingston and Saint-Hyacinthe, the older adults received a letter from their primary care physicians inviting them to contact the field coordinator to make an appointment for the assessments. More information is available at www.imias.ufrn.br [12].

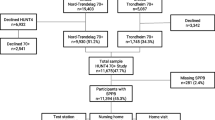

Exclusion criterion and sample

Participants with ≥ 4 errors on the Leganes Cognitive Test (LCT) [13, 14] would be excluded from the IMIAS. This assessment was performed in each follow-up wave. This is a tool adapted for older people with low levels of education, who can screen out cognitive deficits that compromise their ability to understand the tests. In this study, 1725 older adults were included. The flowchart of the final sample of the 2014 IMIAS follow-up wave is shown below in Fig. 1.

Measures

Pain assessment

Participants were asked about pain symptoms in the last month by the question: “Have you been bothered by pain in the last month?” The answer was coded “yes” for presence of pain symptoms and “no” for absence of pain symptoms. In addition, those who answered “yes” were asked about the presence of pain in 12 areas (back, hips, knees, legs, feet, hands, wrists, arms, shoulders, stomach, head, neck, or other area) [15]. For these analyses, symptoms of back pain (BP) and lower limb pain (LLP) were taken into account.

Physical performance

Physical performance was accessed using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), a validated instrument that examines balance, gait speed, and lower limb strength by a sit-up-from-a-chair test. The SPPB tests were carried out by IMIAS researchers.

The balance test consists of the ability to stand for up to 10 s with the feet positioned in three ways: together side by side, in a semi-tandem position and in a tandem position); the gait speed test is done by measuring the time taken to complete a 3 m or 4 m walk; and lower limb strength is assessed by the time taken to stand up from a chair five times [16, 17].

Each SPPB component has scores ranging from 0 (zero) to 4 (four) points. The total SPPB score is obtained by adding the scores of each test, ranging from zero (worst performance) to 12 points (best performance) [18]. Poor physical performance was categorized as < 8 points and good physical performance as 8 points or higher [19].

Covariates

Sex (male or female), study site (Kingston, Saint-Hyacinthe, Tirana, Manizales and Natal), and age were considered covariates when we assumed their potential influences on the association between pain symptoms and physical performance. Education was measured using site-specific tertiles of years of study, categorized as “low,” “intermediate” and “high”. Income sufficiency was classified as "very well, “satisfactory” and “unsatisfactory".

The number of chronic conditions was obtained by self-report according to the Survey of Women's Health and Aging [20]. Such conditions include diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, cancer, chronic respiratory disease, rheumatic disease, and brain disease diagnosed by a physician. The number of chronic diseases was classified into three categories: 0–1, 2–3, and > 3.

Depressive symptoms were accessed by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [21, 22]. This tool is designed to screen for depressive symptoms experienced in the week prior to the assessment and is widely used in older populations [23]. The score is obtained according to the frequency of symptoms (0 = never or rarely; 1 = sometimes; 2 = frequently; and 3 = most often or always). The total score ranges from 0 to 60 points. Higher scores suggest higher frequency of depressive symptoms. The cut-off point of the tool is 16 points.

Ethic aspects

IMIAS was approved by the Ethics Committee of all study sites: In Saint-Hyacinthe (Canada) by the Research Centers of the University of Montreal Hospital Complex; The Queen's University (Kingston/Canada); the Albanian Institute of Public Health; the Research Ethics Boards of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (Natal/Brazil, Ethics Research Committee, Onofre Lopes University Hospital 481/10), and the University of Caldas (Manizales/Colombia). All volunteers signed a consent form to participate in IMIAS.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square test and the T-test were used for descriptive analyses to assess the differences in the distributions of pain variables, SPPB, and covariates between men and women. Differences between categories were attested by the Adjusted Standard Residuals. Bivariate associations between the categories of pain variables and SPPB were also obtained using the chi-square test.

For multivariate analyses, LLP and BP were grouped into a single variable “LLP or BP”. Three binary logistic regression models were used to estimate the independent association between LLP or BP and SPPB categories. Model 1 consisted of only LLP or BP. For Model 2, sex, age, study site, education, income sufficiency, and BMI were added. For Model 3, CES-D and number of chronic conditions were added for complete adjustment.

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 21.0 (SPSS). Regression coefficients for the linear models were estimated with 95% CI and p-value ≤ 0.05. Significant p-values are marked with an asterisk (*).

Results

The results of frequencies distribution are presented in Table 1. The sample consists of 1725 individuals from 5 locations: 328 from Kingston, 345 from Saint-Hyacinthe, 363 from Tirana, 372 from Manizales, and 317 from Natal. Additionally, Table 1 displays demographic, clinical, and functional data, as well as the distribution of pain variables. Among the sample of older men, the highest significant frequencies of self-reported general pain were found in Tirana (72.8%, p < 0.05). Also, significantly higher distributions of self-reported general pain were identified in older women from Tirana (86.1%, p-value < 0.05).

The distributions of the LLP or BP categories were significantly different in the older people across the research sites. The highest frequencies of LLP or BP were found in older women from Manizales (33.5%, p-value < 0.05). Older men from Saint-Hyacinthe showed higher frequencies of LLP or BP, but this distribution was not significant. The frequency distributions of the SPPB categories are also shown in Table 1. Significant differences in the distributions of the SPPB categories were found in Tirana, Manizales, and Natal. The highest frequencies of the SPPB < 8 category were in men (21%, p-value < 0.05) and women (30%, p-value < 0.05) in Manizales.

Table 2 displays the bivariate analysis between self-reported pain variables and Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) categories. The SPPB was significantly associated with all pain variables (p < 0.01). 84.2% of older people with SPPB < 8 points had general pain (p-value < 0.05). Likewise, almost 40% of volunteers with SPPB < 8 points had LLP or BP.

The results of the multivariate analysis between LLP or BP, covariates, and SPPB are presented in Table 3. In the unadjusted model (1), LLP or BP was significantly associated with reductions in SPPB (OR = 0.40, 0.30 to 0.53 95% CI, p < 0.01). In model 2, self-reported LLP or BP was also associated with SPPB (OR = 0.41, 0.30 to 0.56 95% CI, p < 0.01). In the third model, self-reported LLP or BP was again associated with the risk of reductions in SPPB (OR = 0.48, 0.35 to 0.66 95% CI, p < 0.01).

Discussion

This study aimed to analyze the relationship between self-reported pain and physical performance in community-dwelling older people participating in the International Mobility in Aging Study (IMIAS). The main results of the study indicate that pain is a factor that negatively affects physical performance. In other words, pain is strongly associated with low physical performance, even when sociodemographic and clinical factors are taken into account.

Significant differences in the distributions of general pain were identified in Saint-Hyacinthe, Tirana, Manizales, and Natal; however, the highest frequencies were in older people outside Canada. These results suggest that ethnic differences can influence the perception of pain, as identified in the study by Holt & Waterfield [24]. In addition, the influence of ethnic and cultural aspects seems to affect the perception of pain intensity, especially chronic pain [25]. The differences in the frequency distributions of self-reported general pain between countries found in this study corroborate previous research and deserve attention once these differences can affect pain management by patients and health professionals [26].

The other important topic to consider is that lower back and lower extremity pain are common problem among older people. Factors contributing to the development of pain in these locations in older adults include age-related changes in the spine and joints, osteoarthritis, osteoporotic vertebral fractures, obesity, and previous injuries [27, 28]. We observed that these types of pain had a significant relationship with greater risk of reduced SPPB. As identified by previous studies [29, 30], our results also show LLP and BP playing an important role in physical performance decline in older population. In addition, restrictive BP is independently associated with a decline in the physical function of the lower limbs [31], which may suggest that the assessment and management of these types of pain should be carried out together in clinical practice.

Moreover, pain is a limiting factor in the production of maximum torques and load support. This process could be explained by the appearance of increased generalized muscular inhibition, observed in people who report greater intensity of pain [32]. Pain intensity is considered to be negatively associated with reduced functional capacity, thus inferring that individuals with greater pain intensity may have lower physical performance [33]. Pain also can generate “kinesiophobia” a term defined as “irrational, excessive, and limiting fear of movements and physical activities, resulting from a feeling of vulnerability to a possible physical injury” [34]. The presence of fear of movement, predicts possible pain and can have repercussions on mobility, strength, and conditioning. This could largely explain the significant associations in the low SPPB, in which the presence of pain would lead to the appearance of kinesiophobia, which in turn would induce a reduction in the level of physical activity and consequently affect physical performance. This sets in motion a sedentary behavior resulting from the chronic diseases present, accompanied by more pain; a vicious cycle that feeds back on itself.

It is important to highlight that the high pain intensity reported in older adults becomes a barrier to adherence to the practice of physical activities [35]. There is a relationship between the volume of exercises practiced by the older people and the presence of complaints of chronic pain, especially in women, where those with the highest number of complaints also had a lower volume of exercises practiced [36]. On the other hand, frequency, duration, and intensity of exercises are associated with less reports of chronic pain [37].

Regarding chronic conditions, the presence of three or more was identified as a factor associated with poor physical performance in our sample. Along with painful symptoms, the presence of several chronic conditions affects pain management strategies and can determine physical functioning in aging, as pointed out by Ilves and colleagues [38]. Additionally, chronic conditions can affect mental health status, leading to depression, which in turn can worsen pain perception and lead to poor performance [39]. This aspect is directly related to another significant result found in this study: CES-D scores above 16 were risk factors for poor physical performance. Depressive symptoms are associated with reduced physical performance in the older adults and this relationship is apparently mediated by pain symptoms [40, 41].

Low level of education was significantly associated with the risk of poor physical performance. This result is in line with a large sample study (11,394 older people) which identified marked reductions in physical performance scores measured by the SPPB according to low educational levels [42]. We believe that the combination of multi-morbidity, the presence of depression and socioeconomic vulnerability, which is common in developing countries, can accentuate negative results in the functionality and health of the older adults. Older people who are more likely to develop chronic conditions generally have higher levels of depression [39] and it is possible that the presence of musculoskeletal pain could exacerbate this risk. However, this behavior could be bidirectional, as depression exacerbates pain perception, but increased pain intensity can contribute to the development and/or worsening of depression, contributing to performance limitation [2].

Although functional decline occurs naturally with aging, the level of this decline varies according to the presence of several factors, including social inequality and poverty throughout life [35]. Social inequalities can act as a mediator in the relationship between painful symptoms and low performance in older people in several ways. A previous study with IMIAS data revealed that physical performance in the aging is negatively affected when the individual experiences economic adversity during adulthood [43]. Older people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds may have had more physical work during life-course trajectories, which can increase their risk of chronic conditions that cause pain and lead to low performance.

Some potential limitations of this study deserve to be considered. The inclusion only of older people living in the community in a limited age group (between 65 and 74 years old), did not allow us to infer whether the findings would also apply to oldest populations. However, this study has strong points, such as the population samples used, due to their origin in several different locations, which guarantees socioeconomic and cultural diversity among the participants, with a wide range of exposures to adverse situations throughout the course of life. In addition, our study presents information that can be used in the elaboration of health policies aimed at health care for the older people, considering that pain can be an impacting component on the health, physical performance and quality of life.

With this in mind, health professionals should be encouraged to develop adequate protocols for adaptive and individualized physical activity strategies for older people with limitations due to pain. These protocols should have as their main objective, pain management approaches based on exercises in order to reduce the limitation due to pain. It is necessary to consider that this type of approach, together with pharmacological therapy, is part of a strategy aimed at the management of chronic pain, since prolonged periods of reduced levels of physical activity can have an important impact on the health and functionality of older adults. It is imperative to encourage older adults with chronic pain to remain active as an integral part of a healthy aging program.

In summary, the presence of painful symptoms is related to reduced physical performance in community-dwelling older people even when adjusted for other clinical and sociodemographic factors. It is important to prioritize the assessment of painful symptoms in the aging, in order to create prevention and care strategies that can minimize the impact of pain on the functionality and quality of life of this population.

References

Loeser JD, Melzack R (1999) Pain: an overview. Lancet 353(9164):1607–1609. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01311-2

Ritchie CS et al (2023) Impact of persistent pain on function, cognition, and well-being of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 71(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1111/JGS.18125

Wegener ST, Castillo RC, Haythornthwaite J, MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ (2011) Psychological distress mediates the effect of pain on function. Pain 152(6):1349–1357. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAIN.2011.02.020

“The Global Burden of Disease: Generating Evidence, Guiding Policy | Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.” http://www.healthdata.org/policy-report/global-burden-disease-generating-evidence-guiding-policy (accessed Jul. 14, 2021).

Hsu FC et al (2009) Association between inflammatory components and physical function in the health, aging, and body composition study: a principal component analysis approach. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64(5):581–589. https://doi.org/10.1093/GERONA/GLP005

Pavasini R et al (2016) short physical performance battery and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0763-7

Kendall JC et al (2016) Neck pain, concerns of falling and physical performance in community-dwelling Danish citizens over 75 years of age: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Public Health 44(7):695–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816666414

Fowler-Brown A, Wee CC, Marcantonio E, Ngo L, Leveille S (2013) The mediating effect of chronic pain on the relationship between obesity and physical function and disability in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 61(12):2079–2086. https://doi.org/10.1111/JGS.12512

Fernandes SG et al (2022) Relationship between Pain, fear of falling and physical performance in older people residents in long-stay institutions: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(19):12014. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH191912014

“Ageing and health.” https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed Feb. 28, 2023).

Shankar A, McMunn A, Demakakos P, Hamer M, Steptoe A (2017) Social isolation and loneliness: prospective associations with functional status in older adults. Health Psychol 36(2):179–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/HEA0000437

Gomez F et al (2018) Cohort profile: The International Mobility In Aging Study (IMIAS). Int J Epidemiol 47(5):1393-1393H. https://doi.org/10.1093/IJE/DYY074

García De Yébenes MJ, Otero A, Zunzunegui MV, Rodríguez-Laso A, Sánchez-Sánchez F, Del Ser T (2003) Validation of a short cognitive tool for the screening of dementia in elderly people with low educational level. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 18(10):925–936. https://doi.org/10.1002/GPS.947

Caldas VVDA, Zunzunegui MV, Freire ADNF, Guerra RO (2012) Translation, cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Leganés cognitive test in a low educated elderly Brazilian population. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 70(1):22–27. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0004-282X2012000100006

Bélanger E et al (2018) Domains and determinants of a person-centered index of aging well in Canada: a mixed-methods study. Can J Public Health 109(5–6):855. https://doi.org/10.17269/S41997-018-0114-X

Treacy D, Hassett L (2017) The short physical performance battery. J Physiother 64(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2017.04.002

van den Berg M et al (2016) Video and computer-based interactive exercises are safe and improve task-specific balance in geriatric and neurological rehabilitation: a randomised trial. J Physiother 62(1):20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPHYS.2015.11.005

Freire AN, Guerra RO, Alvarado B, Guralnik JM, Zunzunegui MV (2012) Validity and reliability of the short physical performance battery in two diverse older adult populations in Quebec and Brazil. J Aging Health 24(5):863–878. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264312438551

Pérez-Zepeda MU, Belanger E, Zunzunegui MV, Phillips S, Ylli A, Guralnik J (2016) Assessing the validity of self-rated health with the short physical performance battery: a cross-sectional analysis of the international mobility in aging study. PLoS ONE 11(4):e0153855. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0153855

Fried LP, Bandeen-Roche K, Guralnik JM (2019) “Women’s Health and Aging Studies. In: Danan G, Dupre ME (eds) Encyclopedia of gerontology and population aging. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 1–7

Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB (1997) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging 12(2):277–287. https://doi.org/10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.277

Tavares Batistoni SS, Neri AL, Bretas Cupertino APF (2007) Validity of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale among Brazilian elderly. Rev Saude Pub 41(4):598–605. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102007000400014

Ros L, Latorre J, Aguilar M, Serrano J, Navarro B, Ricarte J (2011) Factor structure and psychometric properties of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) in older populations with and without cognitive impairment. Int J Aging Hum Dev 72(2):83–110. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.72.2.A

Holt S, Waterfield J (2018) Cultural aspects of pain: a study of Indian Asian women in the UK. Musculoskeletal Care 16(2):260–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/MSC.1229

Bates MS, Edwards WT, Anderson KO (1993) Ethnocultural influences on variation in chronic pain perception. Pain 52(1):101–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(93)90120-E

Narayan MC (2010) Culture’s effects on pain assessment and management. Am J Nurs 110(4):38–47. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000370157.33223.6D

Fujiwara A et al (2021) Prevalence and associated factors of disability in patients with chronic pain: an observational study. Medicine 100(40):E27482. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000027482

Wong AY, Karppinen J, Samartzis D (2017) Low back pain in older adults: risk factors, management options and future directions. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13013-017-0121-3

Pereira LSM et al (2014) Self-reported chronic pain is associated with physical performance in older people leaving aged care rehabilitation. Clin Interv Aging 9:259–265. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S51807

Hicks GE, Sions JM, Velasco TO (2018) Hip symptoms, physical performance, and health status in older adults with chronic low back pain: a preliminary investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 99(7):1273–1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APMR.2017.10.006

Reid MC, Williams CS, Gill TM (2005) Back pain and decline in lower extremity physical function among community-dwelling older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60(6):793–797. https://doi.org/10.1093/GERONA/60.6.793

Henriksen M, Rosager S, Aaboe J, Graven-Nielsen T, Bliddal H (2011) Experimental knee pain reduces muscle strength. J Pain 12(4):460–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPAIN.2010.10.004

Kroska EB (2016) A meta-analysis of fear-avoidance and pain intensity: the paradox of chronic pain. Scand J Pain 13:43–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SJPAIN.2016.06.011

Siqueira FB, Teixeira-Salmela LF, Magalhães LDC (2007) Analysis of the psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the tampa scale for kinesiophobia. Acta Ortop Bras 15(1):19–24. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-78522007000100004

Lopes MA, Krug RDR, Bonetti A, Mazo GZ (2016) Barreiras que influenciaram a não adoção de atividade física por longevas. Rev Bras Cienc Esport 38(1):76–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbce.2015.10.011

Ferretti F, da Silva MR, Pegoraro F, Baldo JE, De Sá CA (2019) Chronic pain in the elderly, associated factors and relation with the level and volume of physical activity. BrJP 2(1):3–7. https://doi.org/10.5935/2595-0118.20190002

Landmark T, Romundstad P, Borchgrevink PC, Kaasa S, Dale O (2011) Associations between recreational exercise and chronic pain in the general population: evidence from the HUNT 3 study. Pain 152(10):2241–2247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.04.029

Ilves OE et al (2019) Are changes in pain, cognitive appraisals and coping strategies associated with changes in physical functioning in older adults with joint pain and chronic diseases? Aging Clin Exp Res 31(3):377–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40520-018-0978-X

Rizzuto D, Melis RJF, Angleman S, Qiu C, Marengoni A (2017) Effect of chronic diseases and multimorbidity on survival and functioning in elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 65(5):1056–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/JGS.14868

Geerlings SW, Twisk JWR, Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, van Tilburg W (2002) Longitudinal relationship between pain and depression in older adults: sex, age and physical disability. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 37(1):23–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/S127-002-8210-2

Beekman ATF, Kriegsman DMW, Deeg DJH, van Tilburg W (1995) The association of physical health and depressive symptoms in the older population: age and sex differences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 30(1):32–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00784432

Melsæter KN, Tangen GG, Skjellegrind HK, Vereijken B, Strand BH, Thingstad P (2022) Physical performance in older age by sex and educational level: the HUNT Study. BMC Geriatr. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12877-022-03528-Z

Hwang PW, dos Santos Gomes C, Auais M, Braun KL, Guralnik JM, Pirkle CM (2019) Economic adversity transitions from childhood to older adulthood are differentially associated with later-life physical performance measures in men and women in middle and high-income sites. J Aging Health 31(3):509–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264317736846

Acknowledgements

We thank the volunteers who participated in IMIAS.

Funding

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Aging, New Emerging Team; gender differences in immobility for its funding (reference number: AAM 108751). This work was partially supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) (CAPES – PNPD 88887.514407/2020–00).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known financial interests or personal relationships that could influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

IMIAS was approved by the Ethics Committee of all study sites: In Saint-Hyacinthe (Canada) by the Research Centers of the University of Montreal Hospital Complex; The Queen's University (Kingston/Canada); the Albanian Institute of Public Health; the Research Ethics Boards of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (Natal/Brazil, Ethics Research Committee, Onofre Lopes University Hospital 481/10), and the University of Caldas (Manizales/Colombia).

Informed consent

All volunteers signed a consent form to participate in IMIAS.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

da Silva Júnior, E.G., dos Santos Gomes, C., Neto, N.J. et al. Pain symptoms and physical performance in older adults: cross-sectional findings from the International Mobility in Aging Study (IMIAS). Eur Geriatr Med 15, 47–55 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00889-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-023-00889-5