Abstract

Background

Depressive symptoms are common in older adults and predict functional dependency.

Aims

To examine the ability of depressive symptoms to predict low physical performance over 20 years of follow-up among older Mexican Americans who scored moderate to high in the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) test and were non-disabled at baseline.

Methods

Data were from the Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly. Our sample included 1545 community-dwelling Mexican American men and women aged 65 and older. Measures included socio-demographics, depressive symptoms, SPPB, handgrip strength, activities of daily living, body mass index (BMI), mini-mental state examination, and self-reports of various medical conditions. General Equation Estimation was used to estimate the odds ratio of developing low physical performance over time as a function of depressive symptoms.

Results

The mean SPPB score at baseline was 8.6 ± 1.4 for those with depressive symptoms and 9.1 ± 1.4 for those without depressive symptoms. The odds ratio of developing low physical performance over time was 1.53 (95% Confidence Interval = 1.27–1.84) for those with depressive symptoms compared with those without depressive symptoms, after controlling for all covariates.

Conclusion

Depressive symptoms were a predictor of low physical performance in older Mexican Americans over a 20-year follow-up period. Interventions aimed at preventing decline in physical performance in older adults should address management of their depressive symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression, a chronic condition characterized by “loss of interest in activities, changes in weight and sleeping patterns, fatigue, and feelings of guilt and worthlessness,” is among the most prevalent, debilitating, and expensive medical problem worldwide, affecting an estimated 322 million people or 4.4% of the global population in 2015 [1, 2]. In 2008, major depression ranked third of disease worldwide in cost burden and is projected to rank first by 2030, according to the World Health Organization [3]. Although the number of people in the global population with depression increased by 18.4% between 2005 and 2015, the prevalence of depression differs by age, gender, and race/ethnicity [2, 4]. Studies have shown that the prevalence of depression ranges from 5 to 10% among community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older, with the highest prevalence among Hispanics (6.9%) compared to non-Hispanic whites (3.8%) and non-Hispanic blacks (3.6%) [5, 6]. Additionally, women (7.1%) have higher rates of depression compared to men (3.4%) [7].

In the U.S., depression in older adults is a growing public health concern as its population rapidly ages and the demand for mental health resources increases. Studies have projected that adults aged 65 and older will comprise more than 20% of U.S. residents by 2030, and reach a population of approximately 83.7 million by 2050 [8, 9]. In 2012, there was an estimated 0.4 geriatric psychiatrists per 10,000 persons aged 65 and over in the U.S. By 2060, it is projected that there will be 0.2 geriatric psychiatrists per 10,000 population aged 65 and older [4]. In 2013, the healthcare cost of depressive disorders in U.S. was estimated to be $71.1 billion [10]. The upcoming demographic shift will, therefore, lead to an increased number of older adults with depression at increased risk for poor health outcomes and with limited resources to treat their depression.

Physical functioning and mental health in older adults go hand-in-hand. Higher physical function helps older adults to maintain higher levels of physical independence, cognitive function, and quality of life. [11]; whereas, reduced physical performance has been shown to predict incident disability, increase the risk of mortality, and increase all-cause hospitalizations in this population [12,13,14]. Moreover, depression is associated with disability, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality [15,16,17]. Several studies have investigated the relationship between physical function and depressive symptoms [18,19,20,21,22]. These studies are of both cross-sectional [20, 21] and longitudinal in design, mostly conducted in non-Hispanic populations [18, 19, 22]. For example, Everson-Rose et al., using participants from the Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP), found that every 1-point increase in Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) score was associated with a 0.34-point decline in physical performance. [20] Penninx et al., using participants from the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (EPESE), found that, after 4 years, those with depressive symptoms were 1.55 times more likely to have a decline in physical performance [19].

Hispanics are a unique population in several ways. They are a rapidly developing segment of older adults in the U. S., with older Mexican Americans comprising the largest portion of U.S. Hispanics (64.1%) [23]. Older Mexican Americans have a high prevalence of depressive symptoms, type 2 diabetes, and obesity, which are risk factors for developing physical disability [5, 24, 25]. Their minimal access to medical care and low health literacy affect their ability to manage complex conditions, particularly within a rapidly changing healthcare system [26, 27].

Although previous studies show a relationship between depressive symptoms and reduced physical performance, these studies were conducted in non-Hispanic populations, and had less than a 10-year follow-up. Little is known about the long-term effect of depressive symptoms and physical performance over time among older Mexican Americans. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the ability of depressive symptoms to predict low physical performance over 20 years of follow-up among older Mexican Americans who scored moderate to high in the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) test and were non-disabled at baseline.

Methods

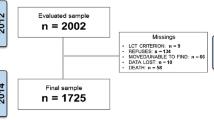

The data used are from the Hispanic EPESE (H-EPESE), an ongoing longitudinal cohort study of Mexican Americans aged 65 and older residing in five southwestern states (Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and California). The original H-EPESE sample consisted of 3050 participants interviewed in 1993–1994 at baseline and who were followed up every 2 or 3 years thereafter. Nine waves of the data have been collected (1993/94–2016). The present study used data collected from baseline to Wave 8 (2012–2013), allowing for approximately 20 years of follow-up data. Information and data for the Hispanic EPESE are available at the National Archive of Computerized Data on Aging [28]. Out of 3050 eligible participants, we excluded 559 with incomplete information on the SPPB, CES-D, and all covariates; 204 who reported needed help or were unable to perform one of seven activities of daily living (ADLs: walking, bathing, grooming, dressing, eating, transferring, or toileting) [29]; and 742 who performed low in the SPPB (score < 7) at baseline. The final analytical sample included 1,545 participants. Excluded participants were significantly more likely than included participants: to be older, male, or unmarried; to have a lower level of education, lower body mass index (BMI), lower SPPB and lower Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores; and to report more limitations in ADLs or the presence of arthritis, diabetes, heart attack, stroke, and hip fracture.

Measurements

Predictor variable

Depressive symptoms were measured with the CES-D, an instrument designed to help quantify depressive symptoms in community surveys [30]. The scale includes 20 items that determine how often specific symptoms were experienced in a 1-week period. Responses are scored on a 4-point scale, with potential total scores ranging 0–60. A score of 16 or greater is used to determine a clinical range for those with depressive symptoms [31]. The scale does not diagnose clinical depression, but has been shown to predict current and future clinical depression [32].

Outcome variable

The SPPB was used to measure physical function. The SPPB is based on three lower extremity tasks which test standing balance, gait (a timed 8-ft walk), and repeated timed chair stands. Each test is scored on a 0–4 scale using previously validated norms and summed for an overall score ranging from 0 to 12 for all three tests. [33] Higher scores indicated better physical performance. Low physical performance was defined as SPPB score < 7 [34]. This index of physical performance has been shown to be reliable and valid for determining incident disability and risk of mortality in the general population and among older Mexican Americans [12, 13].

Covariates

Age, sex, education, marital status, cognitive functioning as measure by MMSE scores [35], measured BMI calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in squared meters [36], handgrip strength measured in kilograms using a dynamometer (Jaymar Hydraulic Dynamometer, model #5030J1, J.A. Preston Corp., Clifton, NJ). [37], and comorbid conditions (self-reported physician diagnosis of hypertension, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, heart attack, stroke, hip fracture, and cancer).

Statistical analysis

Chi-square and t-test were used to examine the distribution of the variables by depressive symptoms at baseline. General Equation Estimation using the GENMOD procedure in SAS was used to estimate the odds ratio of developing low physical performance (SPPB < 7) over 20 years as a function of depressive symptoms. All variables including CES-D were analyzed as time varying (with the potential to change as time progress), except for gender and education. Those participants who died, refused, or were lost to follow-up were included until their last follow-up date (last interview date over the 20 years of follow up). Additional analyses were performed using the general linear mixed models—MIXED procedure in SAS to estimate the change in SPPB over time as a continuous score. All analyses were performed using the SAS System for Windows, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

At baseline (N = 1545), the mean age of the overall sample was 72.0 [Standard Deviation (SD) = 6.1] years, 54.9% were female, 60.7% were married, the mean years of formal education was 5.2 (SD = 4.1), the mean MMSE score was 25.3 (SD = 4.1), the mean BMI was 28.0 (SD = 5.2), the mean SPPB score was 9.0 (SD = 1.4), and the most common medical conditions were hypertension, arthritis, and diabetes (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of the sample by depressive symptoms are presented in Table 1. Overall, 1304 (84.4%) participants reported a CES-D score < 16 and 241 (15.6%) reported a CES-D score ≥ 16. Participants with CES-D ≥ 16 compared to those with CES-D < 16 were significantly more likely to be female (71.4% vs. 51.9%), to be unmarried (53.1% vs. 62.0%), to have lower mean years of formal education (4.5—SD = 3.5 vs. 5.3—SD = 4.2), to have a lower mean SPPB score (8.6—SD = 1.4 vs. 9.1—SD = 1.4), and, in women, to have lower mean handgrip strength (19.8—SD = 5.7 vs. 21.0—SD = 6.0). Lastly, participants with a CES-D score ≥ 16 were also significantly more likely than those with a CES-D score < 16 to report co-morbid conditions such as hypertension (48.9% vs. 40.2%), arthritis (47.3% vs. 33.8%), and diabetes (26.9% vs. 20.9%).

Table 2 shows the Generalized Estimation Equation for low physical performance (SPPB < 7) as a function of depressive symptoms over a 20-year period. Participants with CES-D ≥ 16 had an odds ratio of 1.53—95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 1.27–1.84 of developing low physical performance over time compared to those with CES-D < 16, after controlling for all covariates. Older age (OR = 1.06, 95% = 1.04–1.08), high BMI (OR = 1.03, 95% = 1.02–1.05), arthritis (OR = 1.35, 95% = 1.15–1.59), diabetes (OR = 1.35, 95% = 1.12–1.63), and hip fracture (OR = 2.29, 95% = 1.35–3.89) predicted low physical function over time. Participants who scored high in handgrip strength (OR = 0.95, 95% = 0.94–0.96) and MMSE (OR = 0.93, 95% = 0.91–0.95) were less likely to develop low physical performance over time. When we analyzed SBBP as a continuous score, we found that those with CES-D ≥ 16 experienced greater decline in the SPPB (estimate = − 0.92, Standard Error = 0.10, p-value < 0.0001) than those with CES-D < 16, after controlling for all covariates.

Figure 1a, b shows the unadjusted and adjusted, respectively, means for SPPB score as a function of depressive symptoms over a 20-year follow-up period. Participants with CES-D ≥ 16 and CES-D < 16 showed similar patterns of decline, but those with CES-D ≥ 16 had a steeper decline than those with CES-D < 16 after wave 6, suggesting that the effect of depressive symptoms on physical performance is higher as participants became very old. In those with CES-D < 16, the line tends to stabilize in the last two follow-ups.

a Unadjusted means for short physical performance battery (SPPB) score as a function of depressive symptoms over a 20-year follow-up period. (N = 1545). b Adjusted means for short physical performance battery (SPPB) score as a function of depressive symptoms over a 20-year follow-up period. (N = 1545). CES-D center for epidemiologic studies depression scale

Discussion

This study examined the effect of depressive symptoms on physical performance over 20 years of follow-up among older Mexican Americans who scored moderate to high in the SPPB test and reported no limitations in activities of daily living at baseline. Our findings showed that those with CES-D ≥ 16 were 1.5 times more likely to develop low physical performance (SPPB < 7) over time, after controlling for all covariates. The rate of decline in the SPPB was 0.92 units per year greater among those with CES-D ≥ 16 compared to those with CES-D < 16. Arthritis, diabetes mellitus, hip fracture, and BMI were identified as risk factors of low physical function over time. Participants with greater handgrip strength and higher total MMSE scores were less likely to experience low physical performance over time.

The findings of this study are similar to those from the EPESE and the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam studies [18, 19]. Participants in the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam study with emerging depression and chronic depression experienced a decrease in SPPB scores by 1.30 and 1.12, respectively, over a 3-year follow-up period [18]. Participants in the EPESE study who had depressive symptoms were 1.55 times more likely to experience decline in physical performance over 4 years of follow-up [19].

Several mechanisms may explain the relationship between depressive symptoms and physical performance in this population. Those with depressive symptoms might be likely to score lower on the SPPB, since depression is associated with a decline in systemic physical functioning [38]. Depressive symptoms can cause poor appetite, lower BMI, poor participation in rehabilitation, poor medication adherence, decreased physical activity, impaired immunological function, and increased sleep disturbances, all of which promote physical disability and physical decline [39,40,41]. Studies have shown increased levels of biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in those with depression, [42,43,44] which has been found associated with poor physical performance [45]. Because depression can cause low motivation and energy, those with more depressive symptoms could be less motivated to perform their best on physical function tests [46]. Depression may increase somatic symptoms such as fatigue and pain, which limit cognitive functioning and undermine the effort needed to maintain physical function over time [47]. Factors such as increased fear of falling and social isolation produced by depression among older adults have also been shown to contribute to the development of depressive symptoms and physical decline [48, 49].

Although decline in physical function is a common feature in aging adults, several studies have evaluated the effect of interventions such as physical exercise on depressive symptoms and physical performance [50, 51]. One study from the Lifestyle Interventions and Independence For Elders Pilot study reported that participants with mild or severe depressive symptoms undergoing moderate intensity physical activity had a greater increase in SPPB score and reduction in depressive symptoms over the 6-month intervention compared to participants with mild depressive symptoms in the control group [50]. Another study reported that older Mexican American adults undergoing 4 weekly 1-h group-based exercise classes targeting strength training, endurance, balance, and flexibility displayed decreases in CES-D score at 12 months and 24 months when compared to baseline values [51]. Therefore, physical activity should be encouraged in older adults with depressive symptoms who are at risk of decline in physical performance.

Our study has some limitations. Data concerning medical conditions and depressive symptoms were self-reported, which may lead to greater recall bias than with physician assessment [52]. Since our study used the CES-D scale as a screening tool for depressive symptoms, our findings are not generalizable to individuals clinically diagnosed with depressive mood disorders [30]. Medical conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and Parkinson’s disease were not included in the baseline survey. Our findings are also not generalizable to the larger Hispanic population in the U. S. Participants excluded from the study were less healthy compared to those included, which might have resulted in underestimating the relationship between depressive symptoms and physical performance. Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths; objective measures of SPPB and handgrip strength tests, the use of a large population-based sample of community-dwelling older Mexican Americans, an underserved population with distinct healthcare-related risk factors, such as less access to healthcare services, poorer health outcomes, and lower health literacy [22]. Other strengths include having a follow-up period of 20 years, and longer than that of previous research, including both male and female participants.

Conclusion

In our study, we found that depressive symptoms were highly predictive of low physical performance (SPPB < 7) score in older Mexican Americans, after controlling for several covariates. Future research with larger sample sizes and longer study periods is needed to confirm our findings in other racial/ethnic population-based studies and provide a better understanding of the effect of depressive symptoms on physical performance in older Mexican Americans and the general population.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available at https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACDA/series/546.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition). American Psychiatric Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

World Health Organization (2017) Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHOMSD?sequence=1

Mathers C, Doris FM, Boerma J (2008) The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43942

McCall WV, Kintziger KW (2013) Late life depression: a global problem with few resources. Psychiatr Clin North Am 36:475–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2013.07.001

Blazer DG (2003) Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 58:249–265. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249

Institute of Medicine (2012) The mental health and substance use workforce for older adults: in whose hands. The National Academies Press, Washington. https://doi.org/10.17226/13400

Pratt LA, Brody DJ (2014) Depression in the U.S. Household Population, 2009–2012. NCHS Data Brief 1–8

Day J (1996) Population projections of the united states by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1995 to 2050. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington D.C., United States Bureau of Census

Heo M, Murphy CF, Fontaine KR et al (2008) Population projection of US adults with lifetime experience of depressive disorder by age and sex from year 2005 to 2050. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 23:1266–1270. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2061

Dieleman JL, Baral R, Birger M et al (2016) US spending on personal health care and public health, 1996–2013. JAMA 316:2627–2646. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.16885

Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN et al (2007) Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American college of sports medicine and the American heart association. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39:1435–1445. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616aa2

Mutambudzi M, Chen N-W, Howrey B et al (2019) Physical performance trajectories and mortality among older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 74:233–239. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly013

Ostir GV, Markides KS, Black SA et al (1998) Lower body functioning as a predictor of subsequent disability among older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 53:M491-495. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/53a.6.m491

Falvey JR, Burke RE, Levy CR et al (2019) Impaired physical performance predicts hospitalization risk for participants in the program of all-inclusive care for the elderly. Phys Ther 99:28–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzy127

Lopez AD, Murray CC (1998) The global burden of disease, 1990–2020. Nat Med 4:1241–1243. https://doi.org/10.1038/3218

Black SA, Markides KS, Ray LA (2003) Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 26:2822–2828. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.10.2822

Mutambudzi M, Chen N-W, Markides KS et al (2016) Effects of functional disability and depressive symptoms on mortality in older Mexican-American adults with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc 64:e154–e159. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14432

Penninx BW, Deeg DJ, van Eijk JT et al (2000) Changes in depression and physical decline in older adults: a longitudinal perspective. J Affect Disord 61:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00152-x

Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L et al (1998) Depressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older persons. JAMA 279:1720–1726. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.279.21.1720

Everson-Rose SA, Skarupski KA, Bienias JL et al (2005) Do depressive symptoms predict declines in physical performance in an elderly, biracial population? Psychosom Med 67:609–615. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000170334.77508.35

Russo A, Cesari M, Onder G et al (2007) Depression and physical function: results from the aging and longevity study in the Sirente geographic area (ilSIRENTE Study). J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 20:131–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988707301865

Veronese N, Stubbs B, Trevisan C et al (2017) Poor physical performance predicts future onset of depression in elderly people: Progetto Veneto Anziani longitudinal study. Phys Ther 97:659–668. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzx017

Lopez G (2015) Hispanics of Mexican Origin in the United States, 2013. In: Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2015/09/15/hispanics-of-mexican-origin-in-the-united-states-2013/

Snih SA, Fisher MN, Raji MA et al (2005) Diabetes mellitus and incidence of lower body disability among older Mexican Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60:1152–1156

González BCS, Delgado LH, Quevedo JEC et al (2013) Life-space mobility, perceived health, and depression symptoms in a sample of Mexican older adults. Hisp Health Care Int 11:14–20. https://doi.org/10.1891/1540-4153.11.1.14

Pérez-Escamilla R, Garcia J, Song D (2010) Health care access among Hispanic immigrants: ¿Alguien Esta Escuchando? [Is Anybody Listening?]. NAPA Bull 34:47–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4797.2010.01051.x

Velasco-Mondragon E, Jimenez A, Palladino-Davis AG et al (2016) Hispanic health in the USA: a scoping review of the literature. Public Health Rev 37:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-016-0043-2

Markides KS, Chen N-W, Angel R et al (2016) Hispanic established populations for the epidemiologic study of the elderly (HEPESE) Wave 8, 2012–2013 [Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas]. Natl Arch Comput Data Aging. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36537.v2

Branch LG, Katz S, Kniepmann K, Papsidero JA (1984) A prospective study of functional status among community elders. Am J Public Health 74:266–268. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.74.3.266

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

Boyd JH, Weissman MM, Thompson WD et al (1982) Screening for depression in a community sample: understanding the discrepancies between depression symptom and diagnostic scales. Arch Gen Psychiatry 39:1195–1200. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100059010

Roberts RE, Vernon SW (1983) The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale: its use in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry 140:41–46. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.140.1.41

Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM et al (1995) Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med 332:556–561. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199503023320902

Pavasini R, Guralnik J, Brown JC et al (2016) Short physical performance battery and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 14:215. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0763-7

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12:189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

National Institutes of Health (1998) Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Obes Res 6:51S-209S

Peolsson A, Hedlund R, Oberg B (2001) Intra- and inter-tester reliability and reference values for hand strength. J Rehabil Med 33:36–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/165019701300006524

Penninx BW, Leveille S, Ferrucci L et al (1999) Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: longitudinal evidence from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Am J Public Health 89:1346–1352. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.9.1346

Lenze EJ, Rogers JC, Martire LM et al (2001) The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: a review of the literature and prospectus for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 9:113–135

Stein M, Miller AH, Trestman RL (1991) Depression, the immune system, and health and illness. Findings in search of meaning. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48:171–177. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810260079012

Miller AH, Spencer RL, McEwen BS et al (1993) Depression, adrenal steroids, and the immune system. Ann Med 25:481–487. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853899309147316

Black CN, Bot M, Scheffer PG et al (2015) Is depression associated with increased oxidative stress? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 51:164–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.09.025

Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN et al (2013) So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Med 11:200. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-200

Sousa ACPA, Zunzunegui M-V, Li A et al (2016) Association between C-reactive protein and physical performance in older populations: results from the international mobility in aging study (IMIAS). Age Ageing 45:274–280. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv202

Brinkley TE, Leng X, Miller ME et al (2009) Chronic inflammation is associated with low physical function in older adults across multiple comorbidities. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64A:455–461. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gln038

Roshanaei-Moghaddam B, Katon WJ, Russo J (2009) The longitudinal effects of depression on physical activity. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 31:306–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.002

Barsky AJ, Goodson JD, Lane RS et al (1988) The amplification of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med 50:510–519. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-198809000-00007

Singh A, Misra N (2009) Loneliness, depression and sociability in old age. Ind Psychiatry J 18:51–55. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-6748.57861

Stubbs B, Stubbs J, Gnanaraj SD et al (2016) Falls in older adults with major depressive disorder (MDD): a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int Psychogeriatr 28:23–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104161021500126X

Matthews MM, Hsu F-C, Walkup MP et al (2011) Depressive symptoms and physical performance in the lifestyle interventions and independence for elders pilot study. J Am Geriatr Soc 59:495–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03319.x

Hernandez R, Andrade FCD, Piedra LM et al (2019) The impact of exercise on depressive symptoms in older Hispanic/Latino adults: results from the “¡Caminemos!” study. Aging Ment Health 23:680–685. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1450833

Zandwijk P, Van Koppen B, Van Mameren H et al (2015) The accuracy of self-reported adherence to an activity advice. Eur J Physiother 17:183–191. https://doi.org/10.3109/21679169.2015.1075588

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and Texas Resource Center on Minority Aging Research (R01 AG10939, R01 AG017638, 1P30 AG059301-01 and R01 MD010355). Dr. Rodriguez is a Visiting Scholar at the Sealy Center on Aging and is partly supported by a grant from the Institute of International Education’s Scholar Rescue Fund. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Sarah Toombs Smith, PhD, ELS, Sealy Center on Aging, in article preparation. Dr. Toombs Smith received no compensation for her effort beyond her university salary.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and Texas Resource Center on Minority Aging Research (R01 AG10939, R01 AG017638, 1P30 AG059301-01, and R01 MD010355). The authors acknowledge the assistance of Sarah Toombs Smith, PhD, ELS, Sealy Center on Aging, in article preparation. Dr. Toombs Smith received no compensation for this effort beyond her university salary.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the completion of this study. Mr. JP and Dr. SAS developed the conception and design of the work. Dr. SAS completed data analyses. Mr. JP wrote first draft of the manuscript. Mr. JP, Dr. MAR, and Dr. SAS contributed to the data interpretation and paper revision. All authors meet the authorship requirements as stated in the Uniform Requirement for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study and all research protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Medical Branch.

Human and animal rights

This study only included human participants.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Informed consent

Informed oral consent was obtained from all participants prior the interviewers.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patino, J., Rodriguez, M.A. & Al Snih, S. Depressive symptoms predict low physical performance among older Mexican Americans. Aging Clin Exp Res 33, 2549–2555 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01781-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-020-01781-z