Abstract

In an audit experiment including all German Bundestag and Länder parliamentarians, the article presents an analysis of the question how political communication differs between parties when being addressed ‘privately’ in line or in opposition to their positioning in core issues such as climate change, migration, or the labour market. A content analysis reveals that the populist radical right and left create differing negative narratives about the actual economic situation. While the radical right AfD focuses on blaming government policies with drastic metaphors and insinuating malign ambitions of political elites, the radical left Die Linke criticises the economic elite to profit from economic crises as well as the political elite to play down economic distress. Differences in blame attribution can also be identified in the way both parties criticise official statistics: The AfD accuses the political elites of deliberately manipulating these figures while Die Linke brings forward a more constructive criticism. A quantitative analysis shows that the answers’ tonality as well as the effort put into writing a response does not mirror the parties’ issue positionings. Parliamentarians do not generally take the chance to exploit misinformation that match their positioning in a core issue. Contrary, it is shown that negative tonality and the spread of uncertainty is generally attributed to political communication at the political fringes.

Zusammenfassung

In einem Audit-Experiment unter Einbeziehung aller deutscher Bundestags- und Länderabgeordneten wird im vorliegenden Artikel untersucht, wie sich die politische Kommunikation zwischen den Parteien unterscheidet, wenn sie „privat“ im Einklang mit oder gegen die Positionierung ihrer Partei in ihren jeweiligen Kernthemen angesprochen wird. Eine Inhaltsanalyse zeigt, dass sich die populistische radikale Rechte und Linke dabei unterschiedlicher negativer Narrative bedienen. Während sich die in Teilen rechtsextreme AfD darauf konzentriert, die Regierungspolitik mit drastischen Metaphern zu diskreditieren und einer vermeintlich korrupten politischen Elite bösartige Ambitionen unterstellt, kritisiert DIE LINKE die Wirtschaftselite, von Wirtschaftskrisen zu profitieren, und die politische Elite, die wirtschaftlichen Nöte herunterzuspielen. Unterschiede in der Schuldzuweisung zeigen die politischen Ränder auch in der Kritik an der amtlichen Statistik: Die AfD beschuldigt die politischen Eliten, diese bewusst zu manipulieren, während DIE LINKE eine konstruktive Kritik vorträgt. Eine quantitative Analyse zeigt zudem, dass sich Tonalität und der Aufwand, der in das Schreiben einer Antwort gesteckt wird, nicht durch die parteipolitischen Positionierungen zu den Fragestellungen bestimmen lassen. Die Parlamentarier:innen ergreifen nicht generell die Chance, Desinformationen auszunutzen, die ihrer Position in einem Kernthema entsprechen. Im Gegenteil: Es wird gezeigt, dass negative Tonalität und die Ausbreitung von Unsicherheit generell ein Phänomen der politischen Kommunikation an den politischen Rändern sind.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The rising political polarisation in European party systems is reflected in the political discourse between parties, their politicians, and their electorates (Müller et al. 2017; Egelhofer and Lecheler 2019; Jensen et al. 2012). Furthermore, during an era of ‘populist Zeitgeist’ (Mudde 2004) political communication has been disrupted by the rise of social media platforms that enabled politicians to sideline traditional gatekeepers in order to communicate directly with their constituents (Engesser et al. 2017). This fundamental change of political communication has given rise to aggression, a critical use of abusive language, toxic comments, or hate speech (Kumar et al. 2018; Castaño-Pulgarín et al. 2021). For instance, during the campaigning for the federal election in Germany in 2021 the political fringes aggressively attacked the conservative candidate Armin Laschet (HateAid 2021; Diermeier et al. 2023).

At the same time, confirmation bias plays a significant role in preventing individuals from effectively considering conflicting opinions (Nickerson 1998; Westerwick et al. 2017). This tendency persists even as traditional partisanship has decreased significantly (Dalton and Wattenberg 2002). To avoid experiencing cognitive dissonance, people tend to interpret information based on its alignment with their existing beliefs, especially when it is endorsed by their own political group.

As it becomes more difficult for parliamentarians to identify their supporters, the importance of ‘visible’ characteristics—such as ethnicity or gender—increases to distinguish friends from foes. In ‘private’ communication between parliamentarians and voters these characteristics have been shown to trigger preferential treatment—namely, higher responsiveness or more supportive behaviour (Butler and Broockman 2011; Gell-Redman et al. 2018; Rhinehart 2020).

This polarised world of toxic political communication and high uncertainty has been even described as a deepening epistemic crisis of democracy (Dahlgren 2018). In this context, the following analysis asks whether the way parliamentarians from different parties communicate depends on their ideological distance (issue partisanship) from their constituents:

How does political communication differ between parties when being addressed ‘privately’ on their respective core issues?

In answering this research question, special attention must be paid to the political fringes. In fact, empirical analyses conclude that populism from radical left and right parties can be held responsible for increased polarisation in the public (Castanho Silva 2018).

Innovative experiments have recently taken a different angle and zoomed in on direct ‘private’ communication between parliamentarians and their constituents (Bol et al. 2021; Butler and Broockman 2011; Broockman 2013; Grohs et al. 2016). Unfortunately, these experiments largely focus on selective responsiveness and leave undiscussed the discursive style and language as well as the role of the political extremes. The present analysis bridges this gap by zooming in on German Bundestag and Länder parliamentarians’ language in an audit experiment to gather new insights into the political fringes by looking at private communication with constituents.

The German party system is selected as a field of study as it encompasses all party families including the populist radical left party, Die Linke, and the populist radical right party (PRRP), Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) (Rooduijn et al. 2023). The analysis is based on a citizen’s enquiry experiment and incorporates 1283 answers to citizens’ requests in three highly topical issues: immigration, renewable energy and unemployment.

2 State of research

PRRPs have created a powerful narrative that is ‘rooted in evocative stories drawing on mythical pasts, crisis-driven presents and utopian futures’ (Taş 2022: 128). The main pillars of this narrative seem ‘to endorse an “arrogance of ignorance”, or appeals to common sense and anti-intellectualism’ (Caiani et al. 2021: 214).

By taking the role of a ‘supreme unmasker’ (Ungureanu and Popartan 2020: 42), populist politicians discredit the corrupt elites and their ‘system’ and stage themselves as the exclusive mouthpiece of people’s concerns (Nordensvard and Ketola 2021). By employing a hero-centric storytelling approach both political extremes are in fact comparable (Nordensvard and Ketola 2021). On the populist radical right, it is key to this strategy to defy ‘expert knowledge, statistics, verifiable facts or evidence, and […] [to rely] on common sense and the people’s truth as evidence’ (Hameleers 2020: 154). Hence, PRRPs often blame the media as a putative source of disinformation (Engesser et al. 2017). In contrast, the radical left accuses its political opponents of being dishonest, but less so by explicitly attacking the sources of information such as media information platforms (Hameleers 2020; Engesser et al. 2017).

Also, the German AfD has created a narrative of betrayed people and a corrupt elite (Donovan 2020). In order to battle its competitors’ arguments, AfD representatives turn to ‘substitute half-truths or lies for factual information, as well as to ridicule and attack opponents’ (Conrad 2022: 71). In fact, the toleration of misinformation has turned out to be a phenomenon generally present within the German PRRP. Being addressed by false facts in the immigration issue, the AfD parliamentarians are particularly keen to ‘tailor the truth’ (Diermeier 2023). Also in this regard, the AfD has proven to be ‘a case in point’ (Conrad 2022: 58) of a populistically communicating party. The party not only aggressively attacks ‘the establishment’ but its political communication seems to be generally decoupled from official statistics and ‘the truth’. Taken together, such a behaviour hints to the evolution of an oppositional party on the radical right that might even be considered ‘disloyal’ to the political system (Przeworski 2019).

Hypothesis 1

The anti-establishment critique of populist radical right politicians includes a disqualification of experts and data providers. The same does not hold for the populist radical left.

The style of political communication in Germany changed by the rise of social media and the rising of the AfD as a far-right party in the political system. Social media has been adapted as an unfiltered mass medium of political top-down communication from politicians to their (potential) voters (Waisbord and Amado 2017; Diermeier et al. 2023). Citizens like, comment, criticise, and insult politicians on platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, however, actual discursive interactions between the representatives and the represented are very rare (HateAid 2021; Tagesspiegel 2021).

A possible reason for politicians’ low responsiveness, is constituted by time and budget constraints in their daily work. All Bundestag MPs have the same monthly budget of 19,913 Euros at disposal to spend for their employees’ salaries (Deutscher Bundestag 2024). Parliamentarians who appreciate communication activities might devote more resources to communication experts than to field specialists to satisfy their need of a ‘high performance team’ (own translation, Lettrari 2020). Due to time and budget constraints, politicians possibly focus on requests that they believe help securing the parliamentarian’s office. Communicating with citizens is encouraged not only by intrinsic motivation of ‘good representation’ but rather by extrinsically motivated vote seeking behaviour (Bénabou and Tirole 2003). Audit experiments have shown that answers to constituency requests differ between parliamentarians and their staff, and that staff give less discriminatory answers once they become more experienced (Landgrave and Weller 2019).

In general, private ‘contacting’ (Teorell et al. 2006) through citizens’ enquiries has turned out to be successful to address a German politician. Response rates to citizens writing a letter or an e‑mail to a Bundestag MP range between 63 and 79% (Heß et al. 2018; Bol et al. 2021)—exceptionally high by international comparison.

The experimental literature reveals that higher response rates are generally related to specific characteristics that politicians and enquirers have in common: presumed party affiliation (Costa 2017). Hence, the intention to efficiently answer enquiries is to a certain extent based on extrinsic motivation. Parliamentarians and their staff focus on requests of supposedly partisan citizens. What is more, parliamentarians are found to strategically employ different narratives addressing the same controversial issue depending on the assumed positioning of an enquirer (Grose et al. 2015). Such an adaptive communication strategy rather focuses on ‘other things (partisan causes) more than the truth’ (Chambers 2021: 148) and intends to convince a potential voter to support the parliamentarian in future elections. Therefore, we expect parliamentarians’ answers to reflect whether an enquirer raises and shares a party’s concern in their key issue (e.g., immigration for the AfD; climate change for the Green Party; economic anxieties for Die Linke).

Hypothesis 2

Politicians communication varies depending on whether a politician engages with someone he assumes supports his party or not.

The linguistic political communication literature has turned towards populist parties as their discursive logic follows a specific rationale. A key characteristic of populist ideology and communication is the combination of advocating ‘the people’ and attacking ‘the elites’ (Mudde 2007; Engesser et al. 2017). Hence, populist supporters’ establishment critique can be interpreted as ‘a response to a negative or negatively perceived status quo’ (Giebler et al. 2021: 900). Importantly, their communication strategy might reveal that populists behave ‘disloyal’ to the political system and can thereby be clearly distinguished from other oppositional forces (Przeworski 2019). This is the case once populists discredit established politicians for the sake of their anti-establishment agenda and implicitly challenge the legitimacy of these politicians. In fact, in comparison with established parties’ communication, ‘attacks on the elite are characterised by a relatively harsh tone’ (Engesser et al. 2017: 1119). Left wing populist leaders have sidestepped traditional gatekeepers to attack political opponents publicly and visibly: Populist communication has been characterised by ‘the use of vitriolic and aggressive rhetoric against political rivals, critics and dissidents’ (Waisbord and Amado 2017: 1331). The radical left’s communication allows its supporters to ‘self-identify as aggrieved and humiliated by neoliberal policies and their advocates’ (Salmela and von Scheve 2018). People with left wing populist attitudes are ‘lower in dogmatism and cognitive rigidity, higher in negative emotionality’ (Costello et al. 2022: 135). It can be shown that left wing populism ‘powerfully predicts behavioural aggression and is strongly correlated with participation in political violence.’ (Costello et al. 2022: 135).

A similarly aggressive rhetoric is attributed to the populist radical right whose communication is coined by ‘impoliteness and political incorrectness, […] name calling, insults and stylistic devices such as all caps and exclamation marks (Enli 2017: 58). Also, PRRP, applying exclusion-oriented narratives and attacking (ethnic) minorities, have used hate speech (Caiani et al. 2021; Hallin 2019).

AfD politicians have proven full members of their party family by using the typically aggressive language and by creating a narrative that the German elite has generally conspired against its people that the party had sworn to defend (Diermeier and Niehues 2022; Stahl 2019). It does not come as a surprise that these powerful narratives leave their mark on citizens’ attitudes and trigger a negative image of elites and immigrants (Heiss and Matthes 2020).

However, evidence concerning offensive and aggressive rhetoric employed by populist parties is mostly based on social media communication. We hypothesise that discreditation of political elites, inflation of the ‘true people’s concerns’, and ‘dramatization’ (Caiani et al. 2021: 210) of the status-quo is part of a general populists’ discursive business model on the political right and left—even when compared to other oppositional parties.

Hypothesis 3a

Populist politicians’ critique of the established elites is mirrored by a generally more negative tonality of their communication.

Furthermore, populist located at the political fringes and all over the EU capitalise on economic uncertainty (Gozgor 2022). Traditionally, in times of economic uncertainty, the radical left tends to mobilise its supporters with demands for more redistribution and state interventionism (Hibbs 1977). More generally, economic turmoil has been shown to drive electorates into the arms of populists who blame the elites for inadequately supporting their people (Golder 2016). Also, scholarship has argued that the populist radical right profits the strongest from economic uncertainty (Norris and Inglehart 2019). As a mechanism behind the link between economic uncertainty and support for the radical right a ‘lack of personal control’ is identified that translates into support for a clear radical agenda (Kakkar and Sivanathan 2017). In fact, for AfD voters, the feeling of being at the mercy of someone else and having lost control over their own life seems to be a decisive characteristic for party support (Bergmann et al. 2017). German Chancellor Olaf Scholz even characterised the AfD as a ‘bad mood party’ that profits from conveying insecurity (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2023).

Moreover, existing literature suggests that increased economic and political uncertainty tends to restrain both household consumption and business investment. This occurs as individuals and businesses adopt a cautious ‘wait and see’ approach in response to uncertain conditions (Bernanke 1983; Romer 1990). Consequently, actively contributing to political and economic uncertainty can result in adverse consequences for the real economy, potentially reinforcing a self-fulfilling cycle of negative outcomes.

Hypothesis 3b

Populist politicians’ critique of the established elites is mirrored in a stronger emphasis of present and future uncertainties.

3 Experimental design and operationalisation

Investigating how linguistic polarisation has entered ‘private’ communication between citizens and their parliamentarians, the present analysis is based on an audit experiment caried out with all German Bundestag and Länder parliamentarians. 1283 out of the 2503 politicians that were approached in January 2021 provided an answer (response rate: 51.3%). Ethical considerations concerning the deception of parliamentarians and their staff are summarised in Appendix 1.Footnote 1 Based on the discussed experimental literature, comparable enquiries were drafted in the three important political issues—immigration, renewable energies, and unemployment—during the COVID 19-pandemic (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2022). The artificial enquiries were submitted by a citizen who is ‘concerned’ about one of the three issues and asks for a general assessment. In order to flag out a specific discursive background, the enquirer quotes a (flawed) piece of information that actually prevails in a specific electorate and asks the parliamentarian to confirm this piece of misinformation.

In line with the AfD supporters’ overestimation, an immigration vignette asks whether ‘actually’ 48% of immigrants in Germany were unemployed (true value in 2020: 14.4%, Federal Employment Agency 2021a). In line with the Green Party supporters’ underestimation, a renewable energy vignette asks whether the renewable energy share of total electricity consumption lied ‘merely’ around 35% (true value in 2020: 45%, Federal Environment Agency 2020). Thus, a citizen ‘concerned’ about immigration reproduces the negative view of AfD supporters on the labour market performance of immigrants. A citizen ‘concerned’ about climate change reproduces the green supporters’ doubts on the progress of renewable energy expansion in Germany. Finally, the third vignette is sent out by a citizen ‘concerned’ about the labour market during the pandemic and asks whether the unemployment rate rose to 24% as the average of the German population believes (true value: 5.9%, Federal Employment Agency 2021b).Footnote 2 Hence, parliamentarians receive topic specific requests that include a piece of misinformation as an indication of partisanship.Footnote 3

Parliamentarians’ e‑mail addresses were available publicly or supplied upon request from Bundestag and Länder parliaments including information on gender, faction and government participation. In order to account for a potentially greater importance of citizens’ enquiries for directly elected politicians, the mode of election (list vs. directly elected candidates) was extracted from the project Abgeordnetenwatch.Footnote 4 To address the different motivations of governmental versus oppositional representatives in the respective parliaments, a government variable was coded. In order to evaluate the linguistic features of communication with assumed partisans, data on parties’ issue positioning and salience for the topics immigration (liberal to restrictive), environment (environmental protection to economic growth), and economy (radical left to radical right) as well as the salience of anti-establishment and anti-elite rhetoric (no importance to great importance) were extracted from Chapel Hill Expert Survey (2020).Footnote 5

In line with Bol et al. (2021) two different accounts were created with the traditional German e‑mail provider t‑online based on common male names and surnames.Footnote 6 Having sent the e‑mails in January 2021, election campaigns and parliamentary holidays were avoided. To minimise the chance of detection as an artificial enquiry or as spam, the e‑mails were released in two waves, each spanning several days, and were worded to purport to come from a constituent.Footnote 7 Each parliamentarian received one e‑mail and the three issues were randomised over each parliamentary faction. In sum, the set-up yields a 3 × 2 × 2 experiment with three vignettes being send out by two aliases in two waves.Footnote 8

From the comparison between the signatures below the e‑mail with the parliamentarians’ names we construct an indicator to determine whether answers were self-written or sent by staffers.Footnote 9 The text and content analysis is based on all 1283 answers.Footnote 10 A qualitative analysis pays particular attention to the objects of the underlying negative political communication. Two independent coders identify the target (‘blame attribution’) of negative language as well as the way how official sources of statistics are defied. In line with Gibbs (2012), the concluding content analysis focusses on parties’ common storytelling and regular issue-specifically employed metaphors.

The quantitative analysis draws on the length of each e‑mail as a first indicator of parliamentarians’ and their staffers’ effort.Footnote 11 In order to track differences in the use of language between German parties, we exploit the well-established and tailor-made sentiment dictionary for political communication by Haselmayer and Jenny (2017). The dictionary includes 5001 German words important to political communication on a negativity scale from 0 (not negative) to 4 (very negative).Footnote 12 As suggested, we assign a tonality score to every sentence by selecting the most negatively coded word. To assess the sentiment of each e‑mail we take the arithmetic mean of all sentences. This ‘fine grained measure of negativity’ (Haselmayer and Jenny 2017: 2625) serves as a starting point for our linguistic analysis. As a robustness check we replicate our findings using the German Google BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) deep learning algorithm to classify the sentiment of e‑mails. The BERT-based classification model rests on 5.4 million texts from Twitter, Facebook, and hotel ratings and is therefore suitable for analysing shorter texts such as e‑mails (Guhr et al. 2020). In contrast to a dictionary, the neuronal network rates each e‑mails’ tonality (‘positive’, ‘negative’ or ‘neutral’) based on a context specific evaluation of the employed language.

To measure uncertainty, we scan emails for the presence of specific keywords associated with uncertainty. These keywords include terms like ‘uncertain’, ‘uncertainty’, ‘insecure’, and ‘insecurity.’ We then create a binary variable, assigning a value of 1 when an email contains any of these uncertainty-related keywords and a value of 0 when it does not (Fig. 1).

4 Empirical results

The manual coders note that linguistically the parliamentarians’ responses differ from what is known about the polarising political communication in social media. First, ‘insults and stylistic devices such as all caps and exclamation marks’ (Enli 2017: 58), are largely absent in the politicians’ 1283 answers. Second, the enquirers themselves are not subject to hostility, even if they hold a different opinion from ‘their’ representatives. In contrast, the coders confirm that ‘concerned’ citizens are almost always taken seriously. Harsh critique and negative language are in contrast directed either at the political opponents or at the severity of the respective issue (the economy/the labour market, climate change, immigration).Footnote 13

4.1 Populist narratives: how trust in official statistics is undermined

The experimental set-up confronted politicians with an actually prevailing piece of misinformation that could easily be invalidated by referring to the respective statistics. The following qualitative analysis of the responses zooms in on the target (e.g. the elite vs. the general situation), the context, and the implications of these negatively connotated messages.

First, when being addressed with an overestimation of the unemployment rate during the pandemic, many AfD politicians quote the official statistics, but only to add that those numbers might not reflect the severity of the actual situation. The economic situation is described as ‘scandalous’ (ID 745) and ‘catastrophic’ (ID 508, ID 1120), the damage caused by government politics is evaluated as ‘immeasurable’ (ID 679), and the AfD expects a ‘giant wave of insolvency and poverty’ (ID 218). In line with their role as the ‘supreme unmasker’ (Ungureanu and Popartan 2020: 42), AfD answers advise citizens not to ‘get fooled’ (ID 162, ID 1453) by the ‘official numbers published in mainstream media’ (ID 1414). In fact, the presented misinformation is judged as ‘plausible’ (ID 1696) for the future development because the economic difficulties ‘cannot yet be forecasted’ (ID 2033) and can neither ‘be defined exactly’ (ID 2331). Without directly using an uncertainty related wording as measure by our quantitative indicator, the party stokes fears about a putatively insecure future. More generally, the definition of the unemployment rate is described as a ‘question of interpretation’ (ID 2486).

Second, when being addressed with the underestimated share of renewables in the energy consumption, AfD parliamentarians attack governments without addressing statistical questions in detail. The populist radical right stresses the critique of ‘horrendous’ (ID 30) energy prices due to the expansion of renewables. A large share of renewable energies is evaluated as a risk for the electricity supply that ‘can hardly be stabilised’ (ID 34) in times of ‘dark doldrums’ (‘Dunkelflaute’) (ID 197, ID 1643, ID 1663, ID 2229, ID 2444). Official statistics would ‘fool’ (ID 525) the people as prices for renewables were ‘sugar-coated’ (ID 507). The party’s anti-renewable energy policy platform is enhanced with outrage over ‘Merkel’s wind-megalomonia’ (‘Merkelschen Windkraftgrößenwahn’) (ID 880) that is allegedly triggering a ‘asparguous-like’ (‘Verspargelung’) (ID 880, ID 919, ID 1517, ID 2397) destruction of the environment. In summary, the answers spread a severe pessimism and insecurity far beyond questions of environmental policy (‘this cannot go well’, ID 1326). At the same time the political opponent is attacked for putative scaremongering: ‘the greens and their child soldiers are panicking about an imminent apocalypse’ (ID 2397). More generally, some representatives bring forward common climate change denial arguments such as ‘the climate has always changed’ (ID 2444) or CO2 ‘is not causal’ (ID 2339) for global warming.

Finally, doubts regarding official statistics become most explicit when AfD parliamentarians are confronted with the partisan misinformation that 48% of immigrants were unemployed: A respondent suggests the misinformation might at least hold for unemployment rates of immigrants from ‘problem countries’ (ID 407). Several politicians quote the official numbers and add that statistics do not always ‘reflect reality’ (ID 2153) or that they need ‘to be interpreted correctly’ (ID 2320). Several respondents claim actual unemployment rates were ‘misleading’ (ID 885), a ‘political instrument’ (ID 589), or ‘veiled’ (ID 2179) by the political elites. Others assert there was no ‘simple’ (ID 589) answer as information were ‘hardly available’ (ID 1092) or even ‘one of the best kept secrets’ (ID 2471). The fact that ‘poverty migration’ (ID 891, ID 1215) might not be reflected in the unemployment statistics even leads a parliamentarian to demand for ‘real data’ (ID 2395). Thus, the much lower official unemployment rate than the enquirer assumes, is discredited by planting doubts about the intentions of the elite who has a putative interest to manipulate numbers in line with their immigration policy. Symptomatic for the doomsday scenario that the AfD promotes, one parliamentarian simply concludes ‘may god be with us’ (ID 791).

On the other political extreme, also the radical left employs a strong negative tonality. In fact, also radical left parliamentarians attest a ‘disastrous’ (ID 419) economic situation and claim it needs to be prevented that economic elites would dismiss ‘masses of employees’ (ID 1249) during a ‘wave of bankruptcies’ (ID 353). In line with their economic agenda, representatives claim ‘the rich have become richer’ (ID 1565) and demand for a ‘wealth tax for the richest’ (ID 422) or stronger burdens for companies that ‘strongly profited’ (ID 1132) during the pandemic. Also, several parliamentarians criticise that official unemployment statistics have been ‘tricked’ (ID 1280) or ‘sugar-coated’ (ID 721, ID 986, ID 1441, ID 1566), and explain how to derive the ‘actual’ (ID 735) numbers. By arguing for a different definition of the unemployment rate, however, they make sure that the misinformation that was reported by the enquirer is by far too high even if the official statistics would account for additional groups of people. Thus, in contrast to the AfD’s answers, members of Die Linke do not insinuate a greater conspiracy: ‘This number [the corrected unemployment rate] is not concealed by the Federal Agency, but only defined differently’ (ID 2418).

Similarly, the answers to the renewable energy and immigration requests reveal extremely negative wording as detected by the dictionary. At the same time, the context of this word-based tonality varies significantly form the PRRP narrative. A representative refers to ‘droughts, floodings and other environmental catastrophes’ (ID 2118). Another one criticises that costs were ‘rolled off’ (ID 766) to private consumers or to the ‘chronically cash-strapped municipalities’ (ID 2185). Government policies are evaluated as ‘devastating’ (ID 1444). Migration is explained to be oftentimes triggered by ‘war, persecution, displacement, or destruction of livelihood’ (ID 886). Difficulties of the employment situation of immigration are explicated to be due to ‘racism, discrimination in the working environment, [or] problems concerning the admission process’ (ID 1593). Nevertheless, in both topics radical left parliamentarians largely abstain from ‘fake-news’ accusations against the political elite or the sources of statistical information.

We fail to reject Hypothesis 1. First, the AfD primarily blames the political elites, while Die Linke mainly criticises economic elites. Second, the way blame is apportioned differs greatly on the political fringes: the AfD imputes malicious intentions of elites, defies expert knowledge and discredits official sources of information. The party shows clear signs of a ‘disloyal’ opposition (Przeworski 2019). Die Linke sharply criticises the economic elites and accuses the unemployment statistic to be whitewashed but does not impute a greater conspiracy of perpetrators.

4.2 Few partisan differentiations in citizens’ requests

The experimental set-up allows to distinguish between a citizen who is ‘concerned’ about either the labour market during the pandemic, climate change or immigration. Given the deep divisions about these cleavages as well as the time constraints that politicians and their staff face when dealing with a plethora of enquiries, we expect politicians to put more effort into an answer when dealing with a putative partisan and expect less elaborate answers when addressing a putative opponent (H2).

Figure 2Footnote 14 reveals the relationship between effort and partisanship by operationalising effort as individual word count per parliamentarians’ responses as the dependent variable.Footnote 15 We prevent that few extremely long answers drive our results by taking the natural logarithm of our word count as the dependent variable. We specify our models as OLS regressions. Since we suspect the local political culture to matter for response behaviour on the party level, we cluster standard errors on the party level of each parliament.Footnote 16 Controlling for differing resources (parties’ government participation), differing motivation (directly elected candidates) as well as a differing political climate (upcoming state elections), we find a statistically significant party positioning effect for the unemployment stimulus. As expected, economically left-leaning parties provide longer answers than economically right-leaning parties when being addressed by a putative partisan.Footnote 17

Contrary, despite the signalled partisanship by the ‘concerned’ enquirer, a stronger anti-immigration or pro-environment party positioning does not translate into longer elaborations on the issue. Apparently, in these very issue-specific requests, also non-partisan politicians seize a chance to convince a constituent who holds opposing political views. Neither is government participation or having been directly elected associated with longer e‑mails. Moreover, in states that face upcoming state elections shorter answers were provided in the unemployment enquiry. Possibly, during election times, parliamentarians have even more limited time resources to engage with constituents in one-to-one enquiries on rather general questions such as the state of the economy. Interestingly, self-signed answers are generally longer—independent of whether or not a politician engages with a putative partisan.

Figure 3 repeats the former OLS specifications but employs each e‑mails’ negativity score based on the dictionary by Haselmayer and Jenny (2017) as the independent variable. As expected, the lengthy answers by economically left-leaning parties mirror the enquirer’s concerns with more negative answers. In contrast to economically more liberal parties, the economic left describes the labour market situation as more critical. However, this finding does not translate in a general rule as anti-immigration and pro-environment parties are not associated with more negative answers to putative partisans in their core issue. Parliamentarians in Germany do not generally dramatize an issue along the party line—as far as the dictionary tonality scores are concerned. Furthermore, in line with their responsibility about the economic status quo, government participation reduces the negativity scores of e‑mails in the unemployment and the immigration enquiry but not in their extensive answers on renewable energies.Footnote 18 Interestingly, the long self-written answers employ a more negative wording in comparison with e‑mails openly answered by staffers or forwarded to third parties. Possibly, staffers are less emotionally engaged in the political debate than the politicians themselves and therefore stick to a more neutral communication style.

Summarizing, we need to qualify Hypothesis 2. Neither do parliamentarians generally put more effort into e‑mails when addressing a constituent who putatively holds views compatible with party positioning. Nor do parliamentarians categorically jump on the bandwagon of a ‘concerned’ citizen and demonise the current situation when being addressed in their core issue. In contrast to their staffers, however, parliamentarians seem to generally pick more negative words. Also, we remain cautious in interpreting the results because the share of variance explained by some of our models remains rather low.

4.3 Populism as a driver of negative language and uncertainty?

Possibly, the general partisanship analysis reveals few comprehensive findings because negativity of politicians’ communication is generally driven by populist parliamentarians—on the left and right—independent of the different stimuli and assumed partisanship. Independent of the specific target of negatively connotated messages, populists’ use of language is expected to be reflected in a generally more negative tonality (H3a). Since populists blame the elite for their handling of any political issue—differently than other oppositional politicians—, a general ‘dramatization’ (Caiani et al. 2021: 210) of the status quo could be used as a stylistic device to uncover the establishments’ putative failures and stress economic uncertainties (H3b).

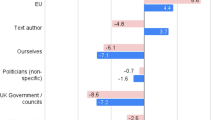

Figure 4 shows that higher salience of anti-establishment and anti-elite rhetoric actually go along with a more negative tonality of representatives when answering citizens’ enquiries. The party that entails the strongest anti-elite salience by far is represented by the German PRRP, AfD. On the radical left, Die Linke is classified significantly less anti-elitist, however, the distance to the remaining parties is large. As expected by Hypothesis 3, the AfD’s and Die Linke’s tonality when answering citizens’ requests turns out to be more negative than the language employed by their political competitors. This finding also corroborates the stronger ‘negative emotionality’ (Costello et al. 2022: 135) that is attributed to the radical left in comparison to the radical right.

Anti-elite Salience and negativity by party. (Source: Own depiction (Excel) based on Haselmayer and Jenny (2017) and Chapel Hill Expert Survey)

Running pooled OLS regressions over all parliamentarians’ responses, Figs. 5, 6 and 7Footnote 19 quantifies whether anti-elite salience correlates ceteris paribus with a more negative sentiment and reveals which parties’ tonality stands out. Whereas parliamentarians of the AfD have not entered any federal or state government, Die Linke governed in Thuringia, Bremen and Berlin at the time of the enquiries. Hence, when analysing whether populist politicians communicate more negatively, we need to account for government participation on the parliament level. Since we also suspect an upcoming election to result in a heated political environment and directly elected politicians to face higher stakes when dealing with their constituents, we add respective control variables.Footnote 20

Figure 5 displays OLS regression results with expert judgements of anti-establishment and anti-elite rhetoric on the party level as a control. The effect is statistically significant and politically relevant: an increase in expert judgement of anti-elite salience from CDU/CSU to AfD by 8.5 scale points explains around a third of the dictionary-based negativity score’s standard deviation. Figure 5 also zooms in on the party level and reveals which parties drive the negative tonality scores.Footnote 21 Because we are interest in all political fringes, we chose a central party such as the SPD as our reference category. The strongest effect can be found for the two parties that hold the strongest populist-anti-elite policy platforms, Die Linke and AfD. Independent of partisanship, the most fundamental characteristic of populism—namely anti-elite sentiment—seems to explain negative answers to citizens’ requests. Having said that, the Green Party’s tonality is also statistically significant more negative than that of the SPD, however, the effect size is significantly smaller. Moreover, directly elected parliamentarians communicate more negatively but the effect loses its statistical significance if we account for the fact that parliamentarians at the political fringes are less often directly elected. Consistently, self-written answers employ a more negative wording.

As a robustness check, Fig. 6 expands the discussed regressions by replacing the dependent variable with the BERT binary negativity coding and running logistic regression models.Footnote 22 Again, the e‑mails’ negativity is strongly related to the expert judgements of anti-elite salience. However, the party-specific BERT regressions that employ a context-specific definition of negative tonality challenge the distinction made at the political fringes. In contrast to the dictionary-based negativity scores, the BERT regressions indicate that negativity is exclusively driven by the AfD. In fact, the probability of a negatively coded e‑mail is twice as high when contacting an AfD parliamentarian. Possibly, strong negative words by the radical left and in self-written answers are employed in a different context than by the radical right and are therefore categorised as less objectionable by the algorithm.Footnote 23

Finally, Fig. 7 employs our uncertainty indicator as the dependent variable. The indicator takes 1 for all 114 answers that directly refer to uncertainty related words and 0 for all other e‑mails. Descriptively, the share of uncertainty related answers is the highest for the AfD, Die Linke, and the green party. The logistic regression results confirm that anti-establishment parties rather use an uncertainty related wording when answering citizens’ requests. The effects of the Green party, AfD, and Die Linke are similar in size and statistically significant on a 5% or 10% significance level, respectively. None of the control variables shows statistical significance.

In summary, we fail to reject Hypothesis 3a and 3b. Populist parties communicate more negatively and refer to uncertainty more often than their peers. Nevertheless, the differences between dictionary and algorithm-based sentiment analysis motivate further reflection. First, our models are only able to explain a relatively low share of the e‑mails’ tonality and uncertainty referencing. Second, the quantitative sentiment analysis needs to be interpreted in the light of the formerly presented content analyses.

5 Conclusion

In comparison to the well-researched social media discourse, ‘private’ communication in one-to-one citizens’ enquiries differs significantly. Aggressive language almost never targets the enquirer—even when they putatively represent non-partisans. All caps and exclamation marks, common stylistic devices of social media communication (Enli 2017), turn out to be almost entirely absent—even for the AfD. If a parliamentarian invests time to answer an enquiry, they take the enquirer seriously and try to convince them of their party’s positioning.

Furthermore, issue partisanship seems to have little impact on parliamentarians’ answers. Neither are enquiries by putative partisans answered more elaborately, nor do parliamentarians answer more negatively in line with the party’s positioning. These findings and the fact that self-signed answers are longer strengthen the intuition that politicians’ ‘private’ communication behaviour is rather determined by intrinsic motivation and the attempt to also convince non-partisans to vote for their party (Diermeier 2023). Drawing a dire picture of the current situation in their respective core issue is not generally part of German politicians’ toolbox—not even for oppositional parliamentarians.

In contrast, the political fringes are generally identified as sources of negative political tonality and as a source of insecurity in political communication. Nevertheless, the different methodologies employed in the quantitative analyis point to varying conclusions regarding the ranking of the radical left and right. Whereas the dictionary-based calculations corroborate the ‘higher […] negative emotionality’ (Costello et al. 2022: 135) among the populist left, the BERT algorithm attributes aggressive language exclusively to the German populist radical right party.

This putative contradiction can be resolved by identifying how ‘blame attribution’ (Hameleers 2020: 154) as well as ‘scandalization’ (Conrad 2022: 69) play out through different narratives on the radical left and right. The populist left aggressively criticises the political elite to sponsor the economic elite. Nevertheless, the left parliamentarians qualify their criticism of the official unemployment rates by clarifying that even the ‘correct’ numbers lie strongly below what the enquirer reported. Contrary, the AfD assumes that the media is in cahoots with the political establishment and bends statistics to their political agenda. Strong metaphors are employed to create a doomsday scenario for each issue their parliamentarians are addressed with. Instead of convincing voters by political solutions, PRRP answers try to unsettle constituents and create doubt about the political system. This finding was corroborated when—expecting microphones to be turned off in a public event on the German energy crisis in 2022—Harald Weyel, an AfD parliamentarian, stated that ‘hopefully’ the situation in the winter would turn out dramatically (Schindler 2022).

In contrast to recent research that engages with the role of the German PRRP and the civil society (Schroeder et al. 2022), we find that an issue-specific opportunity structure matters little for the AfD’s communication strategy. Independent of a citizens’ request’s content, a ‘concerned’ citizen is exploited as a window of opportunity to advertise their typical PRRP narrative and to sow distrust in the official statistic. This behaviour strengthens the interpretation that the AfD has developed into a party that appears increasingly ‘disloyal’ (Przeworski 2019) to the democratic system in general. The party actively provokes uncertainty by dramatizing whichever economic issue constituents are concerned with and by discrediting parties, government, and administration.

Despite these important lessons, the experiment has some limitations. We do not know whether AfD parliamentarians and their staff stand out because of the young party’s low degree of professionalisation. The fact that the AfD was able to draw upon several very established politicians and staffers right from the start contradicts this intuition, but only future research will reveal in how far more years of experience tame the PRRP’s linguistic and narratological radicalism. Furthermore, we lack information on individual attitudes or individual issue positioning. Respective information would refine our findings concerning party-specific communication and psychological mechanisms at work. What is more, more comparable but clearly partisan stimuli would be preferable to isolate the effect of partisanship on the linguistic style of responses. Also, the differences between results based on dictionary- or algorithm-based sentiment analysis demand further investigation. The main question is whether the two quantitative approaches measure distinct (plausible) varieties of negativity. Possibly, being limited to negative buzzwords, the dictionary overestimates the negativity of left populist in comparison to the deeper linguistic understanding of the algorithm that displays results in line with our qualitative analysis.

All in all, with regards to our overall research question we conclude that political communication differs tremendously between parties—linguistically and through its narratives. Regarding the communication style, however, it is less decisive whether a parliamentarian is addressed in their party’s core issue. What matters is the party’s affiliation to one of the political fringes on the radical left and right. Negativity of politicians’ communication occurs primarily driven by one of these political extremes. However, our content analysis reveals that narratives behind the communication style differ greatly between the radical left and right party, in so far as Die Linke criticises established elites, while the AfD goes one step further by insinuating malicious intent and deliberate misconduct of elites. Hence, scholars need to pay close attention to the implications of an oppositional party that has become disloyal to the German political system. In Germany, it will be of particular interest to observe in which way the newly established pro-redistribution-anti-immigration Wagenknecht party will turn.

Notes

The research outline was approved by the University of Duisburg-Essen’s Ethik Kommission (20-9715-BO) and pre-registered at the Open Science Framework. The experiment meets national and international guidelines for research on humans.

See Appendix Table 1 for the polled information question and Appendix Table 2 for an overview of sampled politicians.

Even though the requests deal with federal issues, they are phrased in a general way that any politician needs to able to address. None of the responses from the Länder level referred to a Bundestag politician as the responsible authority.

Abgeordnetenwatch is a project that aims at improving political transparency. Available information can be retrieved through an API: https://www.abgeordnetenwatch.de/api.

All scales are coded from 0 to 10.

Since the research design does not aim at differentiating answers by constituents gender, we decided not to introduce unnecessary noise by varying gender or the origin of names.

To increase the chances of receiving an answer, the enquirer pretends in the e‑mail to live in the parliamentarian’s constituency. In Germany, most parliamentarians who enter parliament via a party list also run in a constituency. In fact, we checked all parliamentarians from the last parliamentary term in September 2021 (data from Bundeswahlleiter) who entered via a list mandate to see if they were assigned to a constituency. The proportion of parliamentarians who did not run in a constituency is negligible, at 3.58 per cent (16 in total).

Appendix Tables 3 and 4 reveal no systemic impact of alias and wave on responsiveness (randomisation test) and that wave, alias and pre-treatment variables are unrelated to the issue treatment (balance test).

Of course, this indicator can only approximate if an e‑mail was actually self-written. Overall, 68% of all e‑mails were signed by parliamentarians themselves; 28% were answered by staffers; four percent were forwarded to third persons (other parliamentarians, experts, etc.). The differences of parties range from 77% self-signed e‑mails by Die Linke to 63% self-signed e‑mails by CDU/CSU. For the regression analysis, we construct a binary variable that only takes 1 if an answer was self-signed.

Regression analyses reveal no statistically significant differences in response rates between parties, government and opposition, directly elected and list candidates, larger and smaller factions, as well as upcoming elections. Response rates are larger, however, for (better endowed) Bundestag parliamentarians.

The word count enables to differentiate between very short answers of only a few sentences and more elaborate ones represents an indicator for the efforts of the parliamentarians.

The dictionary has been compiled through crowd coding and validated by manual coding of parliamentary debates, party press releases and political news reports. The underlying data is publicly available: https://doi.org/10.11587/7PFLIU. Negative words with a low score include unbreachable/’unüberwindbar’ (0.09), vicious circle/‘Teufelskreis’ (0.1), or buffoonery/Kasperletheater (0.15). Negative words that were coded close to the top of the scale include mendacious/‘lügnerisch’ (3.8), dilettantish/‘stümperhaft, or ‘piss take/’Verarschung’ (3.6).

Appendix Table 5 summarises party specific response rates. Appendix Table 6 contains the summary statistics.

See Appendix table 7 for the regression outputs.

See footnote 10 for a further discussion. Appendix table 8 reveals that differences between the stimuli are the largest for AfD parliamentarians who use 55%% more words for the immigration request (324 words on average) than for the unemployment enquiry (208 words on average).

Further control variables such as gender or faction size are omitted from the regression models for their lack a clear theoretical justification and statistically significant outcomes. Also, adding Bundestag affiliation or regional dummies (e.g. east/west) to the regression yields no significant estimators—despite the higher response rate. All results are available upon request.

Specifications with the pure word count (without having taken the logarithm) reveal that a one-point increase on the left-right positioning scale is associated with an increase in e‑mail length of 14 words in the unemployment request. Since the distance in economic positioning between Die Linke and the FDP ranges around 6.7 points, the coefficient explains the difference of 100 words between the two parties.

All results discussed are dependent on the actual responses and could suffer from post-treatment bias if there was non-randomness in response rates. Namely, if AfD, Green, or Die Linke parliamentarians would rather respond to ‘their’ partisan fake-news, chances would be high that the large share of answers never sent-out in the other requests would be less elaborate or rather negative in tonality. Appendix Table 5 reveals that differences in response rates between parties and treatments are hardly statistically significant. Including control variables these correlations become entirely insignificant (results available upon request). We conclude that redefining outcomes somewhat arbitrarily to avoid post-treatment bias in line with Coppock (2019) is not necessary. Nevertheless, regression with manipulated outcomes strengthen our findings and are also available upon request.

See Appendix Table 9 for the regression outputs.

Again, additional potential controls such as Bundestag MPs, gender, faction size, or regions yield no statistically significant results.

For reasons of multicollinearity, party dummies and party positioning variables have to be included in separate specifications.

The BERT algorithm categorises a single e‑mail as ‘positive’ but 165 e‑mails as ‘negative’. The logit regressions are based on a binary negativity score as dependent variable.

Again, since differences of parties’ response rates are small (see Appendix Table 5), the chances of post-treatment bias remain low. However, slightly lower responsiveness by the AfD means that Table 2 represents a conservative estimation specification. Accordingly, regression results with redefined outcomes following Coppock (2019) strengthen our interpretations regarding the AfD. Results are available upon request.

References

Bénabou, Roland, and Jean Tirole. 2003. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Review of economic Studies 70(3):489–520.

Bergmann, Knut, Matthias Diermeier, and Judith Niehues. 2017. Die AfD: Eine Partei der sich ausgeliefert fühlenden Durchschnittsverdiener? Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 48(1):57–75.

Bernanke, Ben. 1983. Irreversibility, uncertainty, and cyclical investment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 98(1):.

Bol, Damien, Thomas Gschwend, Thomas Zittel, and Steffen Zittlau. 2021. The importance of personal vote intentions for the responsiveness of legislators: a field experiment. European Journal of Political Research 60(2):455–473.

Broockman, David E. 2013. Black politicians are more intrinsically motivated to advance blacks’ interests: a field experiment manipulating political incentives. American Journal of Political Science 57(3):521–536.

Butler, Daniel M., and David E. Broockman. 2011. Do politicians racially discriminate against constituents? A field experiment on state legislators. American Journal of Political Science 55(3):463–477.

Caiani, Manuela, Benedetta Carlotti, and Enrico Padoan. 2021. Online hate speech and the radical right in times of pandemic: the Italian and English cases. Journal of the European Institute for Communication and Culture 28(2):202–218.

Castanho Silva, Bruno. 2018. Populist radical right parties and mass polarization in the Netherlands. European Political Science Review 10(2):219–244.

Castaño-Pulgarín, Sergio Andrés, Natalia Suárez-Betancur, Luz Magnolia Tilano Vega, and Harvey Mauricio Herrera López. 2021. Internet, social media and online hate speech. systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 58, 101608. https://prohic.nl/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/213-17mei2021-InternetOnlineHateSpeechtSystematicReview.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2022.

Chambers, Simone. 2021. Truth, deliberative democracy, and the virtues of accuracy: is fake news destroying the public sphere? Political Studies 69(1):147–163.

Chapel Hill Expert Survey. 2020. 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey. Version 2019.1.

Conrad, Maximilian. 2022. A post-truth campaign: the alternative for Germany in the 2019 European parliament election. German Politics and Society 40(1):58–76.

Coppock, Alexander. 2019. Avoiding post-treatment bias in audit experiments. Journal of Experimental Political Science 6(1):1–4.

Costa, Mia. 2017. How responsive are political elites? A meta-analysis of experiments on public officials. Journal of Experimental Political Science 4(3):241–254.

Costello, Thomas H., Shauna M. Bowes, Sean T. Stevens, Irwin D. Waldman, Arber Tasimi, and Scott O. Lilienfeld. 2022. Clarifying the structure and nature of left-wing authoritarianism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 122(1):135–170.

Dahlgren, Peter. 2018. Media, knowledge and trust: the deepening Epistemic crisis of democracy. Javnost—The Public 25(1):20–27.

Dalton, Russell, and Martin Wattenberg (eds.). 2002. Parties Without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deutscher Bundestag. 2024. Mitarbeiter. https://www.bundestag.de/abgeordnete/mdb_diaeten/1334d-260806. Accessed 27 Mar 2024.

Diermeier, Matthias. 2023. Tailoring the truth—evidence on parliamentarians’ responsiveness and misinformation toleration from a field experiment. European Political Science Review 15:332–352.

Diermeier, Matthias, and Judith Niehues. 2022. Ungleichheits-Schlagzeilen auf Bild-Online: ein Sprachrohr der Wertehierarchie? Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft 32:163–188.

Diermeier, Matthias, Judith Niehues, and Armin Mertens. 2023. Außerhalb der Echokammer: Eine Analyse des Bundestagswahlkampfs 2021 auf Twitter. Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegung Plus 36(1):.

Donovan, Barbara. 2020. Populist rhetoric and nativist alarmism. German Politics and Society 38(1):55–76.

Egelhofer, Jana Laura, and Sophie Lecheler. 2019. Fake news as a two-dimensional phenomenon: a framework and research agenda. Annals of the International Communication Association 43(2):97–116.

Engesser, Sven, Nicole Ernst, Frank Esser, and Florin Büchel. 2017. Populism and social media: how politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Information, Communication & Society 20(8):1109–1126.

Enli, Gunn. 2017. Twitter as arena for the authentic outsider: exploring the social media campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election. European journal of communication 32(1):50–61.

Federal Employment Agency. 2021a. Arbeitslosigkeit im Zeitverlauf: Entwicklung der Arbeitslosenquote (Strukturmerkmale). https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/Statistikdaten/Detail/Aktuell/iiia4/alo-zeitreihe-dwo/alo-zeitreihe-dwo-b-0-xlsx.xlsx. Accessed 13 July 2021.

Federal Employment Agency. 2021b. Jahresrückblick 2020. https://www.arbeitsagentur.de/presse/2021-02-jahresrueckblick-2020. Accessed 22 June 2021.

Federal Environment Agency. 2020. Erneuerbare Energien in Zahlen. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/klima-energie/erneuerbare-energien/erneuerbare-energien-in-zahlen?sprungmarke=strom#strom. Accessed 14 Aug 2020.

Forschungsgruppe Wahlen. 2022. Politbarometer. https://www.forschungsgruppe.de/Umfragen/Politbarometer/Langzeitentwicklung_-_Themen_im_Ueberblick/Politik_II/. Accessed 10 May 2022.

Gell-Redman, Micah, Neil Visalvanich, Charles Crabtree, and Christopher Fariss. 2018. It’s all about race: how state legislators respond to immigrant constituents. Political Research Quarterly 71(3):517–531.

Gibbs, Graham. 2012. Analyzing biographies and narratives. In Qualitative research methods, ed. John Gelissen, 56–72. London: SAGE.

Giebler, Heiko, Magdalena Hirsch, Benjamin Schürmann, and Susanne Veit. 2021. Discontent with what? Linking self-centered and society-centered discontent to populist party support. Political Studies 69(4):900–920.

Golder, Matt. 2016. Far right parties in europe. Annual Review of Political Science 19(1):477–497.

Gozgor, Giray. 2022. The role of economic uncertainty in the rise of EU populism. Public choice 190(1–2):229–246.

Grohs, Stephan, Christian Adam, and Christoph Knill. 2016. Are some citizens more equal than others? Evidence from a field experiment. Public Administration Review 76(1):155–164.

Grose, Christian R., Neil Malhotra, and Robert van Parks Houweling. 2015. Explaining explanations: how legislators explain their policy positions and how citizens react. American Journal of Political Science 59(3):724–743.

Guhr, Oliver, Anne-Kathrin Schumann, Frank Bahrmann, and Hans-Joachim Böhme. 2020. Training a broad-coverage German sentiment classification model for dialog systems. Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020)., 1627–1632.

Hallin, Daniel. 2019. Mediatisation, neoliberalism and populisms: the case of Trump. Contemporary Social Science 14(1):14–25.

Hameleers, Michael. 2020. Populist disinformation: exploring intersections between online populism and disinformation in the US and the Netherlands. Politics and Governance 8(1):146–157.

Haselmayer, Martin, and Marcelo Jenny. 2017. Sentiment analysis of political communication: combining a dictionary approach with crowdcoding. Quality & quantity 51(6):2623–2646.

HateAid. 2021. Hass als Berufsrisiko – Digitale Gewalt im Wahlkampf. HateAid Report 2(9):.

Heiss, Raffael, and Jörg Matthes. 2020. Stuck in a nativist spiral: content, selection, and effects of right-wing populists’ communication on Facebook. Political Communication 37(3):303–328.

Heß, Moritz, Christian von Scheve, and Steffen Zittlau. 2018. Ethnische Diskriminierung durch Bundestagsabgeordnete: Ein Feldexperiment. Soziale Welt 69(4):355–378.

Hibbs, Douglas. 1977. Political parties and macroeconomic policy. American Political Science Review 71(4):1467–1487.

Jensen, Jacob, Suresh Naidu, Ethan Kaplan, Laurence Wilse-Samson, David Gergen, Michael Zuckerman, and Arthur Spirling. 2012. Political polarization and the dynamics of political language: evidence from 130 years of partisan speech. Brookings papers on economic activity., 1–81. [with comments and discussion].

Kakkar, Hemant, and Niro Sivanathan. 2017. When the appeal of a dominant leader is greater than a prestige leader. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114(26):6734–6739.

Kumar, Ritesh, Atul Ojha, Shervin Malmasi, and Marcos Zampieri. 2018. Benchmarking aggression identification in social media. https://aclanthology.org/W18-4401.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2022.

Landgrave, Michelangelo, and Nicholas Weller. 2019. Do more professionalized legislatures discriminate less? The role of staffers in constituency service. American Politics Research 48(5):571–578.

Lettrari, Adriana. 2020. Politische Hochleistungsteams im Deutschen Bundestag: Professionelles Management in Abgeordnetenbüros in Zeiten hyperkomplexer Anforderungen. Bremen: Nomos.

Mudde, Cas. 2004. The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition 39(4):541–563.

Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist radical right parties in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Müller, Philipp, Christian Schemer, Martin Wettstein, Dominique Schulz, Sven Engesser, and Werner Wirth. 2017. The polarizing impact of news coverage on populist attitudes in the public: evidence from a panel study in four European democracies. Journal of Communication 67(6):968–992.

Nickerson, Raymond S. 1998. Confirmation bias: a ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology 2 (2), 175–220. https://pages.ucsd.edu/~mckenzie/nickersonConfirmationBias.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2022.

Nordensvard, Johan, and Markus Ketola. 2021. Populism as an act of storytelling: analyzing the climate change narratives of Donald Trump and Greta Thunberg as populist truth-tellers. Environmental Politics 1–22.

Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2019. Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Przeworski, Adam. 2019. Crises of democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rhinehart, Sarina. 2020. Mentoring the next generation of women candidates: a field experiment of state legislators. American Politics Research 48(4):492–505.

Romer, Christina. 1990. The great crash and the onset of the great depression. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 105(3):.

Rooduijn, Matthijs, Andrea Pirro, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Caterina Froio, Stijn van Kessel, Sarah de Lange, Cas Mudde, and Paul Taggart. 2023. The PopuList 3.0: An Overview of Populist, Far-left and Far-right Parties in Europe. www.popu-list.org.

Salmela, Mikko, and Christian von Scheve. 2018. Emotional dynamics of right- and left-wing political populism. Humanity & Society 42(4):434–454.

Schindler, Frederik. 2022. Wie die AfD die Energiekrise für sich nutzen will. DIE WELT, Vol. 2022, 4

Schroeder, Wolfgang, Samuel Greef, and Ten Jennifer Lukas Elsen Heller. 2022. Interventions by the populist radical rIght in German civil society and the search for counterstrategies. German Politics .

Stahl, Enno. 2019. Die Sprache der neuen Rechten: Populistische Rethorik und Strategien. Stuttgart: Alfred Kröner.

Süddeutsche Zeitung. 2023. Scholz: „Schlechte-Laune-Partei“ AfD baut auf Unsicherheit. Süddeutsche Zeitung, 2023. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/parteien-hamburg-scholz-schlechte-laune-partei-afd-baut-auf-unsicherheit-dpa.urn-newsml-dpa-com-20090101-230603-99-930923. Accessed 26 Oct 2023.

Tagesspiegel. 2021. Wie der Wahlkampf 2021 auf Social Media geführt wurde. https://interaktiv.tagesspiegel.de/lab/social-media-dashboard-bundestagswahl-2021/. Accessed 20 June 2022.

Taş, Hakkı. 2022. The chronopolitics of national populism. Identities 29(2):127–145.

Teorell, Jan, Mariano Torcal, and José Montero. 2006. Political participation: mapping the terrain. In Citizenship and involvement in European democracies: a comparative analysis. A comparative analysis, ed. Jan van Deth, José Montero, and Andreas Westholm. Abingdon: Routledge.

Ungureanu, Camil, and Alexandra Popartan. 2020. Populism as narrative, myth making, and the ‘logic’ of politic emotions. Journal of the British Academy 8:37–43.

Waisbord, Silvio, and Adriana Amado. 2017. Populist communication by digital means: presidential Twitter in Latin America. Information, Communication & Society 20(9):1330–1346.

Westerwick, Axel, Benjamin Johnson, and Silvia Knobloch-Westerwick. 2017. Confirmation biases in selective exposure to political online information: source bias vs. content bias. Communication Monographs 84(3):343–364.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Dan Schläger for his valuable contributions to a former unpublished version of this paper. The author thanks two anonymous referees and the editor for their comments that significantly streamlined the arguments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Diermeier, M. Populist politicians’ rhetoric in ‘Private’ communication: Evidence from a citizens’ enquiry experiment in Germany. Z Politikwiss (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41358-024-00385-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41358-024-00385-7