Abstract

Introduction

Primary peritoneal serous carcinoma (PPSC) is a rare primary malignancy that diffusely involves the peritoneum, indistinguishable clinically and histopathologically from primary serous ovarian carcinoma.

Case

A 62-year-old female who had menopause 16 years back presented with complaints of lump abdomen. Examination revealed a large (20–22 weeks) solid, irregular, partially mobile, non-tender mass arising out of pelvis. MRI of the abdomen showed a 12.2 × 10.2 × 10.5 cm multiloculated, multiseptated solid cystic mass in pelvis having heterogeneous signal intensity with necrosis and haemorrhage. Ovaries, tubes and uterus were normal. On opening, a 10 × 10 cm solid cystic pelvic mass with irregular surface and adherent omentum was found over the UV fold of peritoneum and was sent for frozen section. Pan hysterectomy, BPLND and omentectomy were done, and peritoneal biopsies were taken. Diagnosis of PPSC was made on the basis of microscopy and immunohistochemistry.

Conclusion

The prognosis of PPSC is poor. Median survival rate varies between 7 and 27.8 months, while 5-year survival rates range from 0 to 26.5 %.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Primary peritoneal serous carcinoma (PPSC) is a rare primary malignancy that diffusely involves the peritoneum, indistinguishable clinically and histopathologically from primary serous ovarian carcinoma [1]. Primary peritoneal carcinoma (i.e. serous surface papillary carcinoma) arises primarily from peritoneal cells. The mesothelium of the peritoneum and the germinal epithelium of the ovary arise from the same embryologic origin. Therefore, the peritoneum may retain the multipotentiality allowing the development of a primary carcinoma. PPSC appears to be a part of the hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome as the frequency of BRCA mutations in peritoneal and ovarian cancer is comparable [2]. Patients with germline mutations of BRCA1 develop multifocal PPSC [3, 4]. Studies based on molecular pathogenesis have suggested that HER-2/neu, p53 [5], Wilm’s tumour suppressor protein (WT1), oestrogen and progesterone receptors may be involved in the tumourigenesis of PPSC [6].

Case Report

A 62-year-old G5P4A1 female who had menopause 16 years back presented in OPD with complaints of lump abdomen since 1 month. She had no other significant complaints and no current co-morbidities. There was no family history of malignancy. She gave a personal history of pulmonary tuberculosis, 30 years back for which she had taken complete treatment. Her general physical examination did not show any significant findings. Per abdominal examination revealed a large (20–22 weeks) solid, irregular, partially mobile, non-tender mass arising out of pelvis. Per speculum examination showed a small endocervical polyp. Pervaginally, the mass was found filling the entire pelvis and per rectal examination was normal.

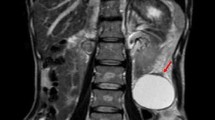

MRI of the abdomen showed a 12.2 × 10.2 × 10.5 cm multiloculated, multiseptated solid cystic mass in pelvis having heterogenous signal intensity with necrosis and haemorrhage. There was compression effect on uterus, bladder and right iliac vessels along with the presence of few enlarged left iliac nodes (largest 9 × 13 mm) and mild pelvic ascites. The uterus and cervix were seen as normal, and there were no comments on ovaries. Her serum CA 125 levels were 18,300 U/L. USG-guided FNAC of ascitic fluid was planned, but no ascites was detected on USG. Hence, exploratory laparotomy was done.

On opening the abdomen, no ascites was found. Peritoneal washings were taken for cytology. Both ovaries, tubes and uterus were normal (Fig. 1a). A 10 × 10 cm solid cystic pelvic mass with irregular surface and adherent omentum was found over the UV fold of peritoneum and was sent for frozen section (Fig. 1b). No upper abdominal disease or palpable lymphadenopathy was found. Frozen section report of pelvic mass revealed malignant epithelial neoplasm (adenocarcinoma) with capsule intact and foci of necrosis. Pan hysterectomy, BPLND and omentectomy were done, and peritoneal biopsies were taken. UV fold of peritoneum was adherent to anterior surface of uterus and posterior surface of bladder.

On gross examination, pelvic mass measured 10 × 10 × 6 cm. Cut surface of the mass was solid with the presence of greyish yellow and greyish white areas. Two polyps were identified on anterior wall of cervix. Part of peritoneum was adherent to anterior wall of uterus, and small whitish nodules were found near right fallopian tube. The omentum was adherent in some places. However, it could be separated easily and was grossly normal. Histopathology showed omentum to be unremarkable.

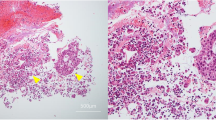

Microscopically, the pelvic mass consisted of moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with mainly papillary growth pattern. Mitotic figures were 3–4/HPF (Fig. 2a). Cervix showed chronic cervicitis with focus of dysplasia at three o’clock, right ovary showed focus of calcification and no viable tumour, paratubal cysts were seen near right FT, and adherent peritoneum showed clusters of atypical cells with inflammation. Uterus with B/L adnexa including bilateral ovaries was normal. There was no clinical/histopathological evidence of endometriosis. Also sent were different parts of peritoneum, bilateral pelvic nodes and omentum which were unremarkable.

On immunohistochemistry, tumour cells expressed CK 7, ER, EMA, PAX 8 and BER-EP4 and were immunonegative for calretinin and WT 1. Because of the presence of normal ovaries and WT 1 negativity, possibility of metastatic ovarian serous adenocarcinoma is ruled out. CDX2 negativity ruled out the presence of metastasis from GIT. Mesotheliomas were also ruled out by the presence of BER-EP4 positivity and the absence of calretinin staining by tumour cells (Fig. 2b–d).

Hence, final diagnosis of primary peritoneal serous carcinoma (PPSC) was made on the basis of microscopy and immunohistochemistry.

Discussion

3.2–21 % of extra ovarian primary peritoneal carcinoma (EOPPC) patients have a history of bilateral oophorectomy for benign disease or prophylaxis in women with a family history of ovarian carcinoma. Age distribution and clinical presentation are indistinguishable from that of advanced stage epithelial ovarian cancer [7]. Patients ordinarily present with non-specific abdominal symptoms and ascites, reported in approximately 85 % of cases [8]. In order to differentiate EOPPC from papillary serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary, the gynaecologic oncology group has stipulated that the following criteria be met [9]:

-

1.

Histology must be predominantly serous or identical to any grade of ovarian papillary serous tumour,

-

2.

the ovaries are of normal size or enlarged by a benign process,

-

3.

the involvement of the extraovarian sites must be greater than the involvement on the surface of either ovary and

-

4.

the ovarian component must be non-existent or confined to surface epithelium or less than 5 × 5 mm within the stroma.

Some authors suggested that genetic events (HER-2/neu overexpression) responsible for malignant transformation in EOPPC may be distinct from those responsible for epithelial ovarian cancer [10].

No morphological features can afford a reliable distinction between EOPPC and metastatic peritoneal carcinomatosis; diagnosis of the latter rests on recognizing a primary tumour, usually in the ovary, fallopian tube or endometrium and less frequently in other organs such as breast, gastrointestinal tract (especially stomach, pancreas), lungs and thyroid gland [10]. Also, EOPPC has to be differentiated from malignant mesothelioma, benign papillary mesothelioma, metastatic peritoneal carcinomatosis, borderline primary peritoneal serous tumour, endosalpingiosis and psammocarcinoma of the peritoneum.

The high values of serum CA-125 levels without diffuse peritoneal involvement are unusual. However, it was so in this case. The post-operative levels of CA-125 came down to normal after 1 month of surgery.

The pathogenesis of EOPPC has been controversial. Some authors believe that embryonic germ cell rests remain along the gonadal embryonic pathway and that EOPPC develops from a malignant transformation of these cells [11]. Other authors contend that field carcinogenesis occurs, with the coelomic epithelium lining the abdominal cavity (peritoneum) and the ovaries (germinal epithelium) manifesting a common response to an oncogenic stimulus [12].

Muto et al. [3] have suggested a multifocal origin with clonality studies. However, Kupryjanzyk et al. [13] have identified others’ findings that are consistent with a unifocal origin. Euscher et al. [14] investigated the WT1 expression in serous carcinoma arising from different sites within the female genital tract and suggested that serous carcinoma may have a different biology based on site of origin.

Family history of multiple cases of breast and ovarian cancer, specifically those who carry cancer-associated mutations of BRCA1/BRCA2, is at increased lifetime risk of primary peritoneal carcinoma even after previous surgery done to remove ovaries, fallopian tubes and uterus. Hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome and associated BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations are particularly prevalent in Jewish women especially of Ashkenazi descent [15].

The prognosis of EOPPC is poor. Median survival varies between 7 and 27.8 months, while 5-year survival rates range from 0 to 26.5 % [16]. Treatment of this malignancy is very similar to that of epithelial ovarian cancer, which includes combination chemotherapy after optimal cytoreductive surgery.

References

Hou T, Liang D, He J, et al. Primary peritoneal serous carcinoma: a clinicopathologicaland immunohistochemical study of six cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:762–9.

Goodman MT, Shvetsov YB. Rapidly increasing incidence of papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum in the united states: fact or artifact? Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2231–5.

Muto MG, Welch WR, Mok SC, et al. Evidence for a multifocal origin of papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Cancer Res. 1995;55:490–2.

Schorge JO, Muto MG, Welch WR, et al. Molecular evidence for multifocal papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum in patients with germline BRCA1 mutation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;80:841–5.

Chivukula M, Niemeier LA, Edwards R, et al. Carcinomas of distal fallopian tube and their association with tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: do they share a common “Precursor” lesion? Loss of heterozygosity and immunohistochemical analysis using PAX2, WT1 and p53 markers. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:858647.

Cross SN, Cocco E, Bellone S, et al. Differential sensitivity to platinum based chemotherapy in primary uterine serous papillary carcinoma cell lines with high vs low HER-2/neu expression in vitro. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:162.e1–162.e8.

Chu CS, Menzin AW, Leonard DGB, et al. Primary peritoneal carcinoma: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1999;54:323–35.

Eltabbakh GH, Piver MS. Extraovarian primary peritoneal carcinoma. Oncology (Willinston Park). 1998;12:813–25.

Bloss JD, Liao SY, Buller RE, et al. Extraovarian peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: a case-control retrospective comparison to papillary adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;50:347–51.

Mills SE, Andersen WA, Fechner RE, et al. Serous surface papillary carcinoma: a clinicopathologicstudy of 10 cases and comparision with stage III–IV ovarian serous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;12:827–34.

Bollinger DJ, Wick MR, Dehner LP, et al. Peritoneal malignant mesothelioma versus serous papillary adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:659–70.

Zinser KR, Wheeler JE. Endosalpingiosis in the omentum: a study of autopsy and surgical material. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6:109–17.

Kupryjanczyk J, Thor AD, Beauchamp R, et al. Ovarian, peritoneal and endometrial serous carcinoma: clonal origin of multifocal disease. Mod Pathol. 1996;9:166–73.

Euscher ED, Malpica A, Deavers MT, et al. Differential expression of WT1 in serous carcinomas in the peritoneum with or without associated serous carcinoma in endometrial polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1074–8.

Casey MJ, Bewtra C. Peritoneal carcinoma in women with genetic susceptibility: implications for Jewish population. Fam Cancer. 2004;3(3–4):265–81.

Fromm GL, Gershenson DM, Silva EG. Papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:75–89.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patni, R., Sethi, N. & Pande, C.L. Primary Peritoneal Serous Carcinoma: An Unusual Presentation. Indian J Gynecol Oncolog 14, 27 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40944-016-0056-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40944-016-0056-2