Abstract

I study the anonymous tax evasion reports collected by the website evasori.info for Italy. I find that tax morale, measured by the number of reports per unit of irregular activity, is negatively associated with the median reported amount. If the utility of reporting evasion is increasing in the amount of the transaction, then, for a fixed cost of reporting, there exists a threshold value above which tax evasion is reported. Stronger tax morale implies a bigger utility for the individual that reports the transaction and, therefore, a lower threshold value above which tax evasion is reported. The empirical analysis features a regression of the median reported evaded amount per economic activity on tax morale, controlling for province fixed effects, economic activity fixed effects and time dummies. I also propose a simulation exercise to estimate the threshold below which tax evasion is reported and its dependence on tax morale. The simulation also shows that the empirical results are not the byproduct of oversampling of small transactions. I conclude that tax morale makes it more difficult to overlook petty evasion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Economists typically think about dishonest behavior through the Becker 1968 model, which predicts that a rational agent will break the law if the expected punishment is low enough. Recent experimental evidence, however, is inconsistent with this framework. The main explanations hinge on the importance of internal motivations, based on the adherence to an internal moral standard, and on customs and social conformity, since deviant behaviors are often punished socially, over and above any legal punishment. The consequence is that people comply with a moral standard even if they suffer an expected monetary loss. In the case of tax evasion, the intrinsic and social motivation to pay taxes based on moral considerations and social pressure is called “Tax Morale” (Erard and Feinstein 1994; Frey 1997; Slemrod 2007) and it has been used to reconcile the predicted evasion rate by the Allingham and Sandmo (1972) and Yitzhaki (1974) models, based on expected penalties and risk aversion only, with the much smaller observed evasion rate (Andreoni and Jonathan 1998; Sandmo 2005).

The founder of the Italian website evasori.info engaged in a very interesting experiment to spread awareness of tax evasion in Italy, in the hope to foster tax morale. In particular, this site allows the users to report, anonymously, their economic transactions with sellers that failed to issue a receipt to avoid paying taxes. The reports are then summarized by economic activity and geographic location. Russo (2013) shows that the number of tax evasion reports in a given area, scaled by the overall size of the illegal sector in the same area, is indeed a measure of tax morale at the local level. Basically the number of reports depends on the mass of individuals that consider evasion dishonest and on how forcefully and often they manifest their convictions, both of which are indicators of tax morale.

In this paper I propose instead an analysis of the incentives behind the reports. An individual will report evasion if the utility from reporting is bigger than the cost. Since the cost of making a report is fixed, if the utility is an increasing function of the transaction amount, say because it is more satisfactory to report big evaders, then there is a threshold amount above which tax evasion will be reported. Stronger tax morale implies a higher utility from reporting, either because evasion is considered less morally acceptable or because it is more difficult to categorize it (Mazar et al. 2008). A higher utility from reporting, in turn, implies a smaller threshold above which tax evasion is reported. The result is a negative relationship between tax morale and the median reported amount. In other words, tax morale makes it more difficult to overlook tax evasion on small transactions. I propose an empirical test of this prediction.

The empirical analysis features a regression of the median reported amount of the transactions with evasion on the measure of tax morale in Russo (2013), the number of reports per unit of irregular activity. The regression features province fixed effects, time dummies and economic activity fixed effects. Since the number of reports and the amount reported are jointly determined, I use an exogenous instrument to obtain consistent estimates. In particular, I use variation in population density to instrument tax morale. I find that a bigger number of reports per irregular activity, which indicates a stronger individual and social norm against evasion, is negatively associated with the median reported amount.

To exclude that this negative regression coefficient is just the by-product of the evasion reporting process, I propose a Montecarlo exercise. The concern is that, within an economy, there are typically more transactions of small amount. Therefore observing more tax evasion reports, whose number is used to measure tax morale, might mechanically deliver a lower median reported value simply out of oversampling of small transactions. The simulation clearly shows how the empirical results are indeed consistent with the idea that the threshold below which tax evasion is considered acceptable decreases with the strength of the norm against evasion. This simulation allows me also to estimate the value of the threshold and the parameters of the function that summarizes its dependency on tax morale.

The analysis of the individual motivations behind the tax evasion reports is important because it stresses that tax evasion on transactions of small amount is often overlooked, although less likely the stronger is the individual and social sanction of evasion. Therefore strengthening tax morale, by making petty evasion more salient, will help reducing its overall amount.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 briefly summarizes the related economic literature. Section 3 illustrates the conceptual framework. Section 4 describes the dataset. Section 5 summarizes the regression results. Section 6 proposes a montecarlo simulation of the evasion reporting process and an estimation of the threshold above which tax evasion is reported. Section 7 discusses the robustness of the empirical results. Section 8 concludes.

2 Related literature

The paper is closely related to the literature on tax morale (Andreoni and Jonathan 1998; Sandmo 2005), that stresses the individual and social motivations to pay taxes over and above the expected sanctions of the Allingham and Sandmo (1972) and Yitzhaki (1974) models. Most of the empirical studies of tax morale, like Orviska et al. (2002), Torgler (2005a, b, 2006), Alm and Torgler (2006), Cummings and Torgler (2009) and Lago Peñas and Lago Peñas (2010), are based on survey measures. Following Russo (2013), I use instead a quasi-experimental measure of tax morale, the number of tax evasion reports on the evasori.info website scaled by the overall size of the informal sector. Moreover, all these previous works did not study tax evasion in single transactions, but rather the effect of tax morale on total tax evasion and on the total mass of evaders. The data on the website evasori.info allow me instead to study the single transactions with evasion and to isolate a new result, namely that tax morale makes petty evasion less likely to overlook.

A more recent strand of literature on tax evasion tries to infer the relationship between tax morale and tax compliance with randomized experiments, where some individuals are treated with a letter that appeals to social and moral norms and that recalls the importance of tax payments. The evidence is mixed: Fellner and Traxler (2013), Pomeranz (2015) and Castro and Scartascini (2015) find no effects of such letters, respectively in Austria, Chile and Argentina; Bott et al. (2014) and Hallsworth et al. (2017) find instead a positive effect on compliance, respectively, in Norway and in the UK.

The paper is also related to the literature on customs and social sanctions. Akerlof (1980) was the first to recognize the importance of interdependency in social behavior, although his work did not explicitly consider tax evasion. Gordon (1989) was instead the first to build a model of tax evasion with social sanctions, stressing that the psychic cost of evasion decreases with the fraction of evaders. Other examples include: Falkinger (1995), that studies the effect of a social norm against tax evasion; Myles et al. (1996), that proposed a model where the cost of evasion depends on a social custom and on conformity, which in turns depends on the fraction of the population that adheres to the custom; Fortin and Villeval (2007), who propose a model of tax evasion with social interactions and conformity, but that are unable to find supportive evidence for it in experimental data; Gino et al. (2009) that show, with an experiment, that cheating increases if there is a favorable social norm or if cheating is a salient behavior. Traxler (2010), that talks about conditionally cooperative agents, in the sense that their individual level of tax compliance depends positively on other agents’ compliance, in line with the survey evidence discussed by Frey and Torgler (2007).

In two related contributions, Gneezy (2005) and Gneezy et al. (2013) show, with experiments, that the propensity to lie increases with the individual benefits for the liar, but that it decreases with the social harm of the lie. Similarly, Gino et al. (2013) find, in an experimental setting, that cheating increases if more individuals benefit from it. Framing these works in the tax evasion setting, they imply that evasion on transactions of small amount should be more frequent than evasion on transactions of big amounts, because a bigger evaded sum creates a bigger damage to the society in terms of foregone tax revenue.

3 Conceptual framework

Suppose that a transaction of amount c takes place between a seller and a buyer and that the seller does not issue a receipt. The receipt is the document on which most tax payments are based, so that the failure to issue one is arguably instrumental to tax evasion. Suppose that the buyers knows about the website evasori.info and must decide whether to report the transaction or not. The cost of reporting it is very small, because it involves just a connection to the site, a registration and few simple mouse clicks, without any fee. Most importantly, this cost is fixed, in the sense that it does not depend on the reported amount: reporting 1 euro or 1000 is actually indifferent from the point of view of the procedure. Suppose that this cost is \(\varepsilon \).

I assume that the utility from reporting is a linear and increasing function of the transaction amount c. In other words, reporting big evasions is more rewarding for the individuals that reporting small evasions. The justification for this assumption is that there is a stronger sense of purpose when reporting a bigger transaction, that involve a greater loss for society as a whole. Alternatively, evasion on transactions of big amounts is more difficult to categorize (Mazar et al. 2008). Categorization, a form of cognitive flexibility, refers to the tendency to rationalize and reinterpret our actions in a self serving way. Stealing a very small amount of money, for instance, might still be consistent with a positive self-image of honesty, and therefore justifiable, because both the cost for the victim and the benefit for the perpetrator are small. The same reasoning applies to petty evasion.

I further assume that both the fixed and the proportional component of the utility from reporting evasion are increasing functions of tax morale \(\mu \). The stronger is tax morale, the harsher the attitude of the buyer towards evasion and, therefore, the bigger the utility. In greater detail, Stronger tax morale fosters attention to a moral standard against evasion, since an anti-evasion social norm is more diffused, resulting in more episodes that remind of the standard and making it more costly to behave differently from it. Moreover, higher tax morale implies also a more difficult categorization of evasion, which is more difficult to reconcile with a self-image of honesty the harsher is the individual and social attitude against evasion.

The buyer reports a transaction of amount c with tax evasion if the utility is bigger than the cost. If \(\omega (\mu )\) is the fixed component and \(\delta (\mu )\) the proportional, then the condition to make a report is \(\omega (\mu ) + \delta (\mu )c \ge \varepsilon \). Rearranging, a transaction with evasion is reported if

In other words, there is a threshold \(T(\mu )\) such that transaction with tax evasion of amount \(c < T(\mu )\) are overlooked and transactions of amount \(c \ge T(\mu )\) are reported. Since tax morale increases both the fixed and the proportional component of the utility, i.e. \(\omega _{\mu }(\mu ) \ge 0\) and \(\delta _{\mu }(\mu ) \ge 0\), I have that \(T_{\mu }(\mu ) \le 0\). Tax morale decreases the threshold above which tax evasion is reported. A lower threshold, in turn, implies reports of lower median amount, since transactions of smaller amount, that were not previously reported, now are. Therefore there is a negative relationship between tax morale and the median reported amount.

To illustrate the point, suppose that there are two cities characterized by two different levels of tax morale \(\mu _{2} > \mu _{1}\) and one individual in each city that completes two transactions of value \(c_{1} > c_{2}\) with two different buyers. Suppose also that \(c_{1}> T(\mu _{1})> c_{2} > T(\mu _{2})\). In city one, since \(c_{1}> T(\mu _{1}) > c_{2}\) only the bigger transaction \(c_{1}\) is reported, so the median reported amount is indeed \(c_{1}\). In city two, since \(c_{1}> c_{2} > T(\mu _{2})\) both transactions are reported and the median reported amount is \((c_{1}+c_{2})/2 < c_{1}\). So there is a negative relationship between tax morale and the median reported amount of evasion.

Furthermore, suppose that the overall amount of tax evasion in city one, \(E_{1}\), is bigger than in city 2, \(E_{2}\), simply because tax morale is weaker in the former. The number of tax evasion reports per unit of irregular activity are then equal, respectively, to \(1/E_{1}\) in city one, where there is one report only, and \(2/E_{2}\) in city two, where there are two reports. Since \(2/E_{2} > 1/E_{1}\), both because the numerator is bigger and the denominator is smaller, I also have that the number of tax evasion reports per unit of irregular activity is a good proxy measure for tax morale, endorsing the methodology in Russo (2013) and all the empirical strategy in this paper.

4 The sample

The website evasori.info allows the users to report any tax evasion they witnessed within Italy. The site is not linked to the Italian tax administration nor to any enforcement agency, so the information in its database is not used for tax enforcement. Its purpose is only to spread awareness of tax evasion, hoping to strengthen a social norm against it, not to denounce specific evaders. The site has been running since 2008 and nearly all major Italian media, including newspapers, magazines, TV and radio, as well as some popular talk shows, covered its operations since the very beginning. Therefore the knowledge of its existence should be diffused and not just an information shared by internet geeks and tax evasion experts only.

The registration on the site and the individual reports are not subject to fees and the user who reports chooses a nickname that allows anonymity. The reports contain the amount of the transaction, the type of economic activity and the location of the evader, summarized by longitude and latitude couples, which however are trimmed to avoid the identification of the reported evader. This feature is indeed consistent with the main task of evasori.info, as clearly expressed on the website, which is not whistleblowing but rather foster tax morale. Taken together, the impossibility to perfectly identify the evader, together with the missing link between the website and the tax enforcement agencies, imply that there is no legal, economic or moral cost imposed on the evader by the report. This is important because I can exclude the possibility of strategic denouncing or revenge denouncing (Yaniv 2001; Mealem et al. 2010) by competitors, ex employees, colleagues or ex partners, which could bias the empirical results. Of course the reports on the webpage can actually be followed by official denounces, which have legal and economic consequences, and the webpage allows the users to disclose if they actually did so, but the evidence (see infra) is that only 5% of users did file an official denounce. Finally, there is no monetary reward for the reports, nor any other retribution other than the feeling of playing a role in the fight against tax evasion.

Given the structure of evasori.info, I can use it to elicit opinions on tax evasion. In particular, the individuals choose to report evasion, conditional on observing it, only if their utility from doing so is high enough. Therefore the number of reports provides information on the utility from reporting. This utility, in turn, is nothing but tax morale, since it reflects the attitude towards tax evasion. Therefore the number of reports reveals information on tax morale. Moreover, even the knowledge of the website is actually a function of tax morale, since strong tax morale individuals have a higher probability to know about it, say because they look up information on tax evasion more often. Thus there will be more reports where more individuals know about the website because of their stronger tax morale.

The raw data that I used in the empirical analysis consist of 63,265 reports made between 2008 and 2013. The number of tax evasion reports varies a lot, both spatially and in time, as summarized by a coefficient of variation of 2.6 in the pooled sample. The left panel of Fig. 1 shows its distribution aggregated by province. Most of the provinces are characterized by few reports, although some of them feature much bigger numbers. In greater detail, the median number of reports in the pooled sample is 38 but the mean is 100, stressing a significant skewness. Moreover, 25% of the observations are below 13 and only 5% of them are above 380. The biggest provinces by total number of reports (summing all years) are also the biggest in terms of population: Roma (8114 reports), Milano (6618 reports), Napoli (3723 reports) and Torino (3600 reports). Similarly, the provinces with the smallest number of reports are among the less populated: Isernia (48 reports), Gorizia (72 reports), Enna (82 reports) and Nuoro (85 reports). Overall, there is a positive correlation between province population and number of reports (0.68), although the 84% coefficient of variation of the number of reports per capita rules out the possibility of reports differentials entirely determined by differences in population size.

Number of reports and shares of irregular activity. Left panel: distribution of the number of tax evasion reports over province-years (pooled sample) from the Evasori.info website. Right panel: distribution of the share of irregular activity as percentage of GDP over province-years (pooled sample) based on ISTAT data

The measure of tax morale is constructed following Russo (2013), dividing the number of reports by the size of the irregular sector. The idea is that, for the same level of irregular activity, which is synonymous with tax evasion or, at a minimum, very correlated with it, a bigger number of reports signals a harsher individual and social attitude against evasion. Alternatively, the same number of reports in two provinces with, respectively, a very small and a very big tax evasion, indicate a much stronger tax morale in the first. The Italian Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) provides data on the irregular sector only at the regional level, although separately by macro-sectors of economic activity. To construct a measure of the irregular sector at the province level, I follow Russo (2013), computing weighted averages of the percentage of irregular activity in each macro-sector with weights equal to the percentage of total value added accounted by these macro-sectors in each province and year. The right panel of Fig. 1 shows the distribution of this measure. The median share of irregular activity is 10% of GDP and the mean is 12%, with a 0.34 coefficient of variation. The smallest share in the sample is 6.9% while the biggest is 22.6% Fig. 2 gives an idea of the geographic variability of tax morale in 2012.

The measure of tax morale in the pooled sample ranges from less than 0.1 reports per unit of irregular activity to more than 350, with 99% of the province-years below 154. To homogenize the sample, I excluded the outlier 1% above 154. The mean number of reports per irregular activity in the resulting sample is 12.7 while the median 6. The correlation between the number of reports and the size of the irregular sector is 0.06, meaning that the differences in the number of reports do not simply reflect differences in evasion and, therefore, that they are informative about the variability of the individual and social attitude towards evasion. This evidence is also confirmed by the high coefficient of variation of the number of reports per irregular activity, 208%. The correlation between the number of reports and the surface area of the province is also very small (0.13). In addition, the coefficient of variation of the number of reports per square kilometer is 243%, which stresses that the reports are also informative on the density of tax morale.

There is a total of 114 economic activities in which the transactions can be categorized at the moment of the report. Some of them collect more than 13,000 reports (coffee shops), while others less than 10 (software development). To make the sample more homogeneous, I pooled similar activities together, resulting into 31 aggregated economic activities (details available upon request). I then computed the median reported amount of evasion in each aggregated activity for each province-year. This left 8960 usable observations. Not all economic activities are reported in each province, so the sample is unbalanced. In Sect. 7, I consider also a different data specifications with zeros in place of the missing reports.

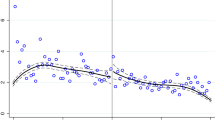

Table 1 shows summary statistics of the median reported evaded amount by economic activity in the pooled sample. The activity with the biggest number of observations (year-province) is coffee shops (531 obs), followed by doctors and dentists (530 obs) and restaurants (523 obs). The activities with the smallest number of observations are instead private clubs (123 obs), culture and recreation (113 obs) and social services (93 obs). The economic activities are very heterogeneous in terms of median reported transaction value. The average ranges from 13 euros for coffee shops to 3163 euros for constructions. Within each category, there is also a huge variability across provinces. Figure 3 is an example of the distributions of the median reported amount for four activities, coffee shops, restaurants, doctors and dentists and lawyers. The distributions are positively skewed because transactions of small amount are, in general, more frequent than transactions of big amount, even conditioning on activity. However, the frequency of big transactions is not always small, as the distribution for lawyers shows.

The number of official reports to the authorities is much smaller than the total number of reports. The average of the ratio of official reports to total reports is 0.05, which means that, on average, 5% of the website reports are followed by official reports. In 25% of the province-years, there is actually less than 1 official report, and in more than 10% of the province years there is no report at all. Conversely, there are also province-years with a very high number of official reports, above 100. The mean number of official reports in the pooled sample is 8.9, with a standard deviation of 19. Since the individuals that reports the transaction to the authorities are arguably more committed to their own anti-evasion conviction, I consider the number of official reports per irregular activity as an indicator of strong tax morale. However, since there very few official reports in the data, and since there are no data for 2008, I will focus attention, in the following empirical analysis, on the total number of reports, and then discuss the additional (weaker) results for this indicator of a stronger attitude in Sect. 7.

One potential problem of the measure of tax morale is that a small number of reports by a large mass of users accounts as a big number of reports by a small mass of users, while tax morale has stronger effects if it is widespread. However the focus of this work is not the assessment of the aggregate consequences of tax morale but rather the analysis of the individual attitude towards evasion, so this should be less of a concern. Moreover, it is not easy to interpret time variation in tax morale, which is the reason why, in Sect. 7 I consider the robustness of the results to a different time aggregation.

5 Empirical results

The empirical model that I estimate is the following:

where \(v_{ijt}\) is the median amount of the reported transactions with tax evasion in province i for the economic activity j in year t, \(m_{it}\) is tax morale, \(X_{it}\) are control variables, \(D_{j}\) are dummies for the \(J=31\) economic activities in which the data are aggregated, \(\eta _{i}\) are province fixed effects, \(\delta _{t}\) time effects and \(\varepsilon _{ijt}\) is the error term.

As main control variables, I use total consumption expenditure and the percentage of internet users (more control variables are discussed in Sect. 7). It is important to control for total expenditures because the median reported evaded amount might be bigger in a province just because the value of all transactions is bigger. It is important to control for internet use because, conditional on the same tax morale, a bigger number of reported transactions in a province might actually be the by-product of a more frequent internet use. In fact the percentage of frequent internet users explains the number of reports per irregular activity (positive and significant coefficient in the first stage regression of the IV estimator, see infra).

The problem with this empirical specification is the endogeneity of tax morale. In greater detail, higher evaded amounts might trigger a stronger public response, which in turn could foster tax morale. To address this endogeneity, I use exogenous variation in population density across province-years to instrument tax morale. First, because population size is positively correlated with the measure of tax morale and so is population density. Second because tax morale is a social phenomenon, being closely related to a notion of social sanction, and more densely populated areas foster tax morale because of the bigger number of social and economic interactions. What I need for the consistency of the IV estimator of \(\beta _{1}\) is that changes in the populations density are not the results of changes in the amount of the transactions with evasion. I think this is not a huge concern because I’m considering a relatively short period of time and because geographical mobility across provinces in Italy is very small. Moreover, the results are robust when controlling for consumption expenditure in several different categories of goods, among which there is also housing (see Sect. 7 for details).

The left panel of Table 2 reports the baseline regressions results without instruments, while the right panel the IV results. The standard errors in brackets are clustered at the province level. The estimated coefficient is around − 2 in the baseline regression and − 4.7 in the instrumental variable regression. In both cases it is significant at the 5% level. The instrument is itself very strong, as stressed by the high F statistic in the first stage regression (details on the first stage regression available upon request). Table 2 also shows that controlling for expenditures and for the number of frequent internet users does not matter for the main result. Overall, there is a negative and significant relationship between tax morale, measured by the number of tax evasion reports per irregular activity, and the median reported value of the transactions with evasion. In the next section, I show that this result is indeed compatible with the conceptual framework according to which tax morale makes it more difficult to overlook petty evasion. Section 7 discusses instead the robustness of this empirical results.

6 Threshold determination

Stronger tax morale implies a bigger utility from reporting evasion and, therefore, a lower threshold above which tax evasion is condemned and reported, resulting in a smaller median reported amount. In the previous sections I reported empirical evidence consistent with this pattern. In this section I try to delve into the mechanism, proposing a montecarlo simulation to estimate this threshold. This exercise also shows that the data are indeed compatible with the conceptual framework that I proposed to rationalize the results, therefore validating the analysis. In a nutshell, the montecarlo exercise is a simulation of the data generating process which, according to the conceptual framework developed in the paper, should have generated the observed tax evasion reports.

The first step entails the estimation of the empirical distribution of the reports, which will be the starting point of the simulations. I start from the raw data, pooling the observations for all provinces, years and economic activities. I proceed with a parametric estimation using the Gamma distribution, because it is the most flexible distribution on a positive support. I estimate the two parameters of the of the Gamma via maximum likelihood to have consistent estimates. The overall fit to the model is actually very good and the resulting estimated distribution is not very different from the one obtained with a non parametric, kernel, estimation.

Next I draw randomly a set of \(N=20{,}000\) observations from this empirical distribution of tax evasion reports. This set represents the universe of all economic transactions with tax evasion. I then sort the set from low to high and denote the observations \(X_{i}\), where \(X_{1}\) is the smallest and \(X_{N}\) the biggest. Extracting several samples of different sizes from this pool and computing the median value in each sample, I obtain a set of sample sizes and median amounts that closely resembles the data, where a number of tax evasion reports (per unit of irregular activity) is coupled with the median reported amount.

The question, then, is what selection criterion of the samples delivers the negative relationship between the sample size, which is the simulation equivalent of the number of reports, and the median reported amount. To choose the criterion, I come back to the conceptual framework. In particular, I postulated that the transactions are reported only if they are above a threshold. This threshold is, in turn, a function of tax morale, with stronger morale associated with a lower threshold. Since tax morale predicts also a bigger number of reports, I need, for the conceptual framework to be correct, a threshold that shifts down as the sample size in the simulation increases. To simplify the exercise and to make it closer to the empirical specification, I assume that the threshold is a linear function of tax morale.

To estimate the parameters of this linear function I look at the pooled sample. To set the intercept \(\hat{T}\), I consider the median reported amount in the provinces with less than one report per irregular activity, which signals a very low tax morale. This median amount is 850 euros, on the basis of which I set \(\hat{T}=276\) euros. By construction, \(\hat{T}\) is such that, if I extract several random samples of fixed size \(\hat{n}\) between \(\hat{T}\) and \(X_{N}\) and then compute the median in each sample, I obtain, on average, 850 euros (note that \(\hat{n}\) does not affect the simulation results).

To estimate the slope, I draw progressively bigger samples, by a discrete factor \(\gamma \), of \(n=\hat{n}+\gamma \) observations from \([\,T(\hat{T},\gamma ,k) ; X_{N} ]\) where \(T(\hat{T}, \gamma , k)=\hat{T}-\gamma \, k\) is the threshold that shifts down as the sample size, or tax morale, increases. In each sample I then compute the median amount m(n). To mimic the empirical range of the number of reports per irregular activity, I set \(\gamma \in \{0;150\}\), for a total of 151 samples of different sizes. The parameter of interest is k, since it controls how the threshold decrease with tax morale.

For given k, this procedure delivers a set of couples (n, m(n)) which resembles the data, so that I can run a regression of m(n) on n. Running this procedure a large number of times, and averaging over the regression coefficients, I obtain \(\beta (k)\), which is the simulation counterpart of the regression coefficient of the median reported amount on the number of reports per irregular activity. Then I run the simulations for different values of k to then chose the value of k that minimizes the difference between \(\beta (k)\) and its empirical counterpart. For the baseline least squares estimate \(\beta _{1}=-2.0\), the result is \(k=1.2\) euros. For the baseline IV estimate \(\beta _{1}=-4.7\), the result is instead \(k=1.9\) euros. Thus 10 more reports of tax evasion shift the threshold above which tax evasion is reported between 12 and 19 euros.

This simulation exercise is also useful to show that the empirical results are not spurious. The concern arises because the distribution of economic transactions is, broadly speaking, positively skewed, since transactions of small amount are more frequent than transactions of big amount. Thus it is possible to find a negative correlation between the number of reports and the median reported amount just because of sampling if the sample size is not big enough. To test if this concern is real, I repeated the simulations setting \(k=0\), which entails random sampling with a fixed threshold. The result is that it is nearly impossible to find a \(\beta _{1}\) as small as the estimated value. For the negative relationship between number of reports and median amount to be as negative as in the data, it is necessary to have a decreasing threshold with the sample size.

7 Robustness and extensions

The sample that I used in the previous analysis in unbalanced, since not all economic activities are reported in each province. To check for robustness, I included a zero if there is no report of evasion for a given economic activity in the province. The sample consists now of 19,159 observations, of which 10,198 are zeros (53% of the sample). I excluded from the regression analysis the small provinces, with less than 200(k) inhabitants,Footnote 1 where most of the observations are zeros. The results are reported in Table 3. Overall, the result still highlight a negative relationship between tax morale and the median reported amount. The coefficients are, in absolute value, smaller than in Table 2, as a consequence of the inclusion of the zeros. Moreover, the standard errors are also smaller, most likely because of the much bigger number of observations.

To further test the robustness of the results, I tried including in the set of regressors several other control variables from the ISTAT database. The results do not change after including the fraction of women, average age and education (primary, secondary and college level). I also controlled for different expenditures: in food, clothes, housing, appliances, health, leisure and services, without any change in the results. I also tried including value added instead of consumption expenditure, without significant changes. The results do not change when controlling for the fraction of self employed individuals, which should be, on average, more prone to tax evasion (Pissarides et al. 1989; Slemrod 2007; Russo 2013) and should therefore have a more lenient attitude.

To further test for robustness, I also grouped the reports every 6 months instead of every year. The results are very similar, with smaller standard errors due to the bigger number of observations. To test the model specification, I also included the square of tax morale in the regression, but the coefficient on this variable was not significant.

The website evasori.info reports also the number of reports that are followed by official reports to the authorities. As I stressed in Sect. 4, the number of official reports per irregular activity is an indicator of a very strong attitude towards evasion, so I tried using it as an alternative measure of strong tax morale. The resulting regression coefficients are very big, much more than in the previous regressions, but they are significant only in the balanced sample with zeros. In greater detail, the OLS coefficient in the balanced panel regressions is − 28, while the IV, obtained with the same strategy as in Sect. 5, is − 57. The results are robust to the inclusion of control variables.

8 Conclusion

The paper studies the incentives behind the tax evasion reports on the Italian website evasori.info and highlights a negative relationship between tax morale and the median reported amount. This evidence is consistent with a simple model where the utility from a tax evasion report is an increasing function of the reported amount, for instance because evasion on big transactions is more difficult to categorize. This, in turn implies that tax evasion is reported only for transactions values above a threshold, which decreases as tax morale increases.

I believe that the empirical result is interesting because it highlights that tax evasion on transactions of small amount is often overlooked and tolerated. However, the stronger is the individual and social attitude towards evasion, the less likely the tolerance. Therefore strengthening tax morale will be particularly helpful at curbing petty evasion, which is often widespread.

Notes

Aosta, Biella, Enna, Gorizia, Isernia, Crotone, Massa-Carrara, Nuoro, Oristano, Rieti, Sondrio, Verbania, Vercelli, Vibo Valenzia.

References

Akerlof, G. A. (1980). A theory of social custom of which unemployment may be one consequence. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 94(4), 749–775.

Allingham, M., & Sandmo, A. (1972). Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 1(3), 323–338.

Alm, J., & Torgler, B. (2006). Cultural differences and tax morale in the US and in Europe. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27(2), 224–246.

Andreoni, J., Erard, B., & Jonathan Feinstein, J. (1998). Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(2), 818–860.

Bott, K. M., Cappelen, A. W., Srensen, E. & Tungodden, B. (2014). Youve got mail: A randomized field experiment on tax evasion. NHH Norwegian School of Economics Working Paper 26/2014

Castro, L., & Scartascini, C. (2015). Tax compliance and enforcement in the pampas evidence from a field experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 116, 65–82.

Cummings, R. G., Martinez-Vazquez, J., McKee, M., & Torgler, B. (2009). Tax morale affects tax compliance: evidence from surveys and an artefactual field experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 70(3), 447–457.

Erard, B., & Feinstein, J. S. (1994). Honesty and evasion in the tax compliance game. Rand Journal of Economics, 25(1), 1–19.

Falkinger, J. (1995). Tax evasion, consumption of public goods and fairness. Journal of Economic Psychology, 16(1), 63–72.

Fellner, G., Sausgruber, R., & Traxler, C. (2013). Testing enforcement strategies in the field: Threat, moral appeal and social information. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11(3), 634–660.

Fortin, B., Lacroix, G., & Villeval, M.-C. (2007). Tax evasion and social interactions. Journal of Public Economics, 91(11), 2089–2102.

Frey, B. (1997). A constitution for knaves crowds out civic virtues. The Economic Journal, 107(4), 1043–1053.

Frey, B., & Torgler, B. (2007). Tax morale and conditional cooperation. Journal of Comparative Economics, 35(1), 136–159.

Gino, F., Ayal, S., & Ariely, D. (2009). Contagion and differentiation in unethical behavior. The effect of one bad apple on the barrel. Psychological Science, 20(3), 393–398.

Gino, F., Ayal, S., & Ariely, D. (2013). Self-serving altruism? The lure of unethical actions that benefit others. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 93(1), 285–292.

Gneezy, U. (2005). Deception: The role of consequences. American Economic Review, 95(1), 384–394.

Gneezy, U., Rockenbach, B., & Serra-Garcia, M. (2013). Measuring lying aversion. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 93(1), 293–300.

Gordon, J. P. (1989). Individual morality and reputation costs as deterrents to tax evasion. European Economic Review, 33(4), 797–805.

Hallsworth, M., List, J. A., Metcalfe, R. D., & Vlaev, I. (2017). The behavioralist as tax collector: Using natural field experiments to enhance tax compliance. Journal of Public Economics, 148(2), 14–31.

Lago Peñas, I., & Lago Peñas., S. (2010). The determinants of tax morale in comparative perspective: Evidence from European countries. European Journal of Political Economy, 26(4), 441–453.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 633–644.

Mealem, Y., Tobol, Y., & Yaviv, G. (2010). Whistle-blowers as a deterrent to tax evasion. Public Finance Review, 38(3), 306–320.

Myles, G. D., & Naylor, R. A. (1996). A model of tax evasion with group conformity and social customs. European Journal of Political Economy, 12(1), 49–66.

Orviska, M., & Hudson, J. (2002). Tax evasion, civic duty and the law abiding citizen. European Journal of Political Economy, 19(1), 83–102.

Pissarides, C. A., & Weber, G. (1989). An expenditure-based estimate of Britain’s black economy. Journal of Public Economics, 39(1), 17–32.

Pomeranz, D. (2015). No taxation without information. American Economic Review, 105(8), 2539–2569.

Russo, F. F. (2013). Tax morale and tax evasion reports. Economics Letters, 121(1), 110–114.

Sandmo, A. (2005). The theory of tax evasion: A retrospective view. National Tax Journal, 58(4), 643–663.

Slemrod, J. (2007). Cheating ourselves: The economics of tax evasion. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), 25–48.

Torgler, B. (2005a). Tax morale in Latin America. Public Choice, 122(1), 133–157.

Torgler, B. (2005b). Tax morale and direct democracy. European Journal of Political Economy, 21(2), 525–531.

Torgler, B. (2006). The importance of faith: Tax morale and religiosity. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 61(1), 81–109.

Traxler, C. (2010). Social norms and conditional cooperative taxpayers. European Journal of Political Economy, 26(1), 89–103.

Yaniv, G. (2001). Revenge, tax informing, and the optimal bounty. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 3, 225–33.

Yitzhaki, S. (1974). A note on ’income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis’. Journal of Public Economics, 3(2), 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I would like to thank the creator of the website evasori.info for the data and for the support. I am very grateful to Dimitris Christelis for the insightful discussions. I would also like to thank the editor and the referees for their comments that helped improving the paper. All remaining errors are mine only.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Russo, F.F. Reporting tax evasion. Econ Polit 35, 917–933 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-018-0096-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-018-0096-4