Abstract

Tax evasion is widespread, always has been, and probably always will be. Variations in duty and honesty can explain some of the across-individual and, perhaps, across-country heterogeneity of evasion. But the stark differences in compliance rates across taxable items that line up closely with detection rates suggest strongly that deterrence is a power factor in evasion decisions. Although the normative theory of taxation has been extended to tax system instruments such as the intensity of enforcement, the empirical knowledge for operationalizing these rules is sparse.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

JEL Classifications

No government can announce a tax system and then rely on taxpayers’ sense of duty to remit what is owed. Some dutiful people will undoubtedly pay what they owe, but many others will not. Over time the ranks of the dutiful will shrink, as they see how they are being taken advantage of by the others. Thus, paying taxes must be made a legal responsibility of citizens, with penalties attendant on noncompliance. But even in the face of those penalties, substantial tax evasion exists – and always has.

Determining the extent of evasion is not straightforward, for obvious reasons. Because tax evasion is both personally sensitive and potentially incriminating, selfreports are vulnerable to substantial underreporting. Moreover, the dividing line between illegal tax evasion and legal tax avoidance is blurry. Under US law, tax evasion refers to a case in which a person, through commission of fraud, unlawfully pays less tax than the law mandates. Tax evasion is a criminal offence under federal and state statutes, subjecting a person convicted to a prison sentence, a fine, or both. An overt act is necessary to give rise to the crime of income tax evasion; therefore, the government must show wilfulness and an affirmative act intended to mislead. Some tax understatement is, however, inadvertent error, due to ignorance of or confusion about the tax law (as is some overpayment of taxes). Although the theoretical models of this issue generally refer to wilful understatement of tax liability, the empirical analyses cannot precisely identify the taxpayers’ intent and therefore cannot precisely separate the wilful from the inadvertent. Nor can they, in complicated areas of the tax law, precisely distinguish the illegal from the legal.

The most careful and comprehensive estimates of the extent and nature of tax noncompliance anywhere in the world have been made for the federal taxes that the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The IRS comes up with its estimates by combining information from random intensive audits with information obtained from ongoing enforcement activities and special studies about sources of income, such as tips and cash earnings of informal suppliers like nannies and housepainters, that can be difficult to uncover even in an intensive audit.

The latest tax gap estimate, released in February 2006 (IRS 2006) but pertaining to the 2001 tax year, estimated the overall gross tax gap estimate to be 345 billion dollars, which amounts to 16.3 per cent of estimated actual (paid plus unpaid) tax liability. Of the 345 billion dollar estimate, the IRS expects to recover 55 billion dollars, resulting in a ‘net tax gap’ – that is, the tax not collected – for tax year 2001 of 290 billion dollars, which is 13.7 per cent of the tax that should have been reported.

About two-thirds of all underreporting happens on the individual income tax; the corporation income tax makes up slightly more than ten per cent and the payroll tax gap makes up about one-fifth of total underreporting. For the individual income tax, understated income, as opposed to overstating of exemptions, deductions, adjustments, and credits, accounts for over 80 per cent of underreporting of tax. Business income, rather than wages or investment income, accounts for about two-thirds of the understated individual income. Taxpayers who were required to file an individual tax return, but did not, accounted for slightly less than ten per cent of the gap.

There are wide variations in the rate of misreporting as a percentage of actual income by type of income (or offset). Only one per cent of wages and salaries and four per cent of taxable interest and dividends are underreported. In large part this is because wages and salaries, as well as interest and dividends, must be reported to the IRS by those who pay them; in addition, wages and salaries are subject to employer withholding. Self-employment business income is not subject to information reports or withholding, and its estimated noncompliance rate is sharply higher. An estimated 57 per cent of non-farm proprietor income is not reported – 68 billion dollars – which by itself accounts for more than a third of the total estimated underreporting for the individual income tax. All in all, over half of underreporting is attributable to the underreporting of business income, of which non-farm proprietor income is the largest component.

All in all, there is substantial evidence that the extent of evasion for sole proprietor income is high compared to such income sources as wages, salaries, interest and dividends, and may be more than half of true income. Other components of taxable income for which information reports are nonexistent or of limited value, such as other non-wage income and tax credits, also have relatively high estimated misreporting rates. The IRS reports (IRS 2006) that the net misreporting rate is 53.9, 8.5, and 4.5 per cent for income types subject to ‘little or no,’ ‘some,’ and ‘substantial’ information reporting, respectively, and is just 1.2 per cent for those amounts subject to both withholding and substantial information reporting.

Little is known about how the level of noncompliance, and its proportion to actual income, varies by income class. One study based on IRS audit data for 1988 suggested that higher-income people evade less, in relation to the size of their true income, than those with lower incomes, but for a number of reasons this study is not conclusive. Other studies suggest that married filers, taxpayers younger than 65, and men have significantly higher average levels of noncompliance than others. Within any group defined by income, age, or other demographic category, there are some who evade, some who do not, and even some who overstate tax liability. It is not known to what extent this heterogeneity is explained by different ‘tastes’ for evasion or different opportunities to evade.

Noncompliance is also a factor with businesses, both in their role as withholding agents for taxes that are not statutorily levied on businesses, and also for taxes that are levied on businesses, such as the corporation income tax. Based largely on operational data, the IRS estimates that noncompliance with the corporation income tax in 2001 was 30 billion dollars, which corresponds to a noncompliance rate of 17 percent. Of this 30 billion dollars, noncompliance by corporations with over 10 million dollars in assets make up 25 billion. But the estimated noncompliance rate of the larger companies is lower, 14 per cent compared to 29 per cent for corporations with less than 10 million dollars of assets. Because these estimates are largely based on deficiencies proposed by the examination teams of operational audits, and because most big corporations are routinely audited, these tax gap estimates are subject to several caveats. Because of the complexity of the tax law, exactly what is actual tax liability – and therefore what is actual tax noncompliance – is often not clear. In any given audit, some noncompliance may be missed, and there will also be mistakes in characterizing as noncompliance what is legitimate tax planning. Knowing that the resolution of the ultimate tax liability is often a long process of negotiation, the tax liability according to the originally filed return, as well as the initial deficiency assessed by the examination team, may be partly a tactical ‘opening bid’ that is neither party’s best estimate of the ‘true’ tax liability.

It is difficult to compare the magnitude and nature of tax evasion in the United States with other countries, in part because no other country has undertaken a broadbased analysis of tax evasion like that undertaken in the United States. Based on less extensive analysis, the Swedish Tax Agency has estimated the total gap as a percentage of taxes at eight per cent in 2000. Although no official estimate for the United Kingdom has been released, a government document has speculated that it is likely that the United Kingdom has a tax gap of a similar magnitude to that of Sweden and the United States. Many studies suggest that noncompliance rates in developing countries are considerably higher.

Economics models have tried to put these facts into a coherent model. The standard economics framework for considering an individual’s choice of whether and how much to evade taxes is a deterrence model in which taxpayers make these decisions in the same way they would approach any risky decision or gamble – by maximizing expected utility – and are influenced by possible penalties no differently than any other contingent cost. Optimal tax evasion depends on the chance of getting caught and penalized, the size of the penalty for evasion, and the individual’s degree of risk aversion.

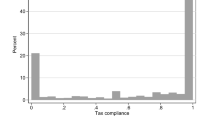

Attempts to empirically verify the predictions of the deterrence model of tax evasion have focused on the effect on evasion of enforcement intensity and the level of tax rates, but have been plagued by the same measurement issues that arise in assessing the magnitude of tax noncompliance. Perhaps the most compelling empirical support for the deterrence model is the cross-sectional variation in noncompliance rates across types of income and deductions. Line item by line item, there is a clear negative correlation between the noncompliance rate and the presence of enforcement mechanisms such as information reporting and employer withholding. A striking example of the link from a lack of deterrence to tax compliance involves state use taxes, which are due on sales purchased from out-of-state vendors but consumed in the state of residence. These taxes are largely unenforceable (except perhaps for some expensive items like cars), and noncompliance rates are in the range of 90 per cent. The effect on noncompliance of the penalty for detected evasion, as distinct from the probability that a given act of noncompliance will be subject to punishment, has not been compellingly established empirically.

Although the deterrence model has dominated the economics literature, some have argued that it predicts a compliance rate much lower than what we actually observe, and that factors such as duty and reciprocal altruism can explain this. Some have argued that many taxpayers comply with tax liabilities because of ‘civic virtue’, and that more punitive enforcement policies may crowd out such intrinsic motivation by making people feel that they pay taxes because they have to, rather than because they want to. Others argue that tax evasion decisions depend on perceptions of the fairness of the tax system or what the government uses tax revenues for. But such individual judgements can be complex; for example, expenditures on warfare might be tolerated in a patriotic period, but rejected during another period characterized by anti-militarism. These patterns suggest that a form of reciprocal altruism may be at work where taxpayer behaviour depends on the behaviour, motivations, and intentions not of any subset of particular individuals, but of the government itself. In support of this view, surveys show a positive relationship across countries between attitudes towards tax evasion and professed trust in government.

There is, however, no clear evidence that tax compliance behaviour can be easily manipulated by the government to lower the cost of raising resources. Appeals to patriotism to induce citizens to pay their taxes (and, often, buy war bonds) are common; the US Secretary of Treasury during the First World War, William Gibbs McAdoo, referred to these campaigns as ‘capitalizing patriotism’. That such campaigns are successful during ordinary (non-war) times in convincing taxpayers to forego the cost-benefit calculus and comply has not been compellingly demonstrated. Recent randomized field experiments in the state of Minnesota and in Switzerland have found no evidence that appeals to taxpayers’ consciences, stressing either the beneficial effects of tax-funded projects or conveying the message that most taxpayers were compliant, had a significant effect on compliance.

The difficulties of separating out whether people pay their taxes because they feel they ‘ought to’ or whether they fear the penalties attendant to not doing so is well illustrated by some evidence from a recent survey sponsored by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS Oversight Board 2006). While 96 per cent of those surveyed in 2005 mostly or completely agreed that ‘It is every American’s civic duty to pay their fair share of taxes’, 62 per cent also said that ‘fear of an audit’ had a great deal or somewhat of an influence on whether they report and pay their taxes ‘honestly’.

Tax evasion has policy implications because it affects the distribution of the tax burden as well as the resource cost of raising taxes. Variations in compliance rates by income class can to some extent be offset by adjustments in the rate schedule, but it is practically impossible to offset variations within an income class, so that evasion creates horizontal inequity because equally well-off people end up with different tax burdens.

Tax evasion also imposes efficiency costs. The most obvious are the resources taxpayers expend to implement and camouflage noncompliance, and the resources the tax authority expends to address this. In addition, when the tax system is otherwise close to optimal it provides a socially inefficient incentive to engage in those activities for which it is relatively easy to evade taxes. For example, because the income from house painting can be done on a cash basis and is therefore harder to detect, this occupation is more attractive than otherwise. Although a supply of eager and cheap house painters undoubtedly is greeted warmly by prospective buyers of that service, the work of the extra people drawn to house painting, or any activity that facilitates tax evasion, would have higher value in some alternative occupation.

The same argument applies to self-employment generally, as the enhanced opportunity for noncompliance inefficiently attracts people who would otherwise be employees. The opportunity for noncompliance can distort resource allocation in a variety of other ways, such as causing companies that otherwise would not find it attractive to set up a financial subsidiary, or set up operations in a tax haven, to facilitate or camouflage abusive avoidance or evasion.

The mere presence of tax evasion does not imply a failure of policy. Just as it is not optimal to station a police officer at each street corner to eliminate robbery and jaywalking, it is not optimal to completely eliminate tax evasion. Recognizing tax evasion introduces a new set of policy instruments whose optimal setting is at issue, such as the extent of audit coverage, the strategy for choosing audit targets, and the penalty imposed on detected evasion. It also invites a rethinking of standard taxation problems.

One important issue is how many resources to devote to enforcing the tax laws. One superficially intuitive rule – increase the probability of detection until the marginal increase of revenue thus generated equals the marginal resource cost of so doing – is incorrect. Although the cost of hiring more auditors, buying better computers and the like is a true resource cost, the revenue brought in does not represent a net gain to the economy, but rather a transfer from private (noncompliant) citizens to the government. The correct rule equates the marginal social benefit of reduced evasion, which is not well measured by the increased revenue, to the marginal resource cost. The distinction suggests that unregulated privatization of tax enforcement, in which profit-maximizing firms would maximize revenue collection net of costs, would lead to socially inefficient overspending on enforcement. The social benefit is related to the reduced risk bearing that comes with reduced tax evasion and a reduction in the resource misallocations generated by evasion. Some have suggested that the basic framework of social welfare maximization is inappropriate, and have argued that there should be a specific social welfare discount applied to the utility of those who are found to be guilty of tax evasion and thus are known to be ‘antisocial’; the standard normative model applies no such discount, so that noncompliant taxpayers do not per se receive a lower social welfare weight than compliant taxpayers.

No one has yet compellingly translated this theoretical characterization of optimal enforcement into a statement about how much evasion should be tolerated. But its implication for interpretation of the tax gap is clear and was stated by former IRS Commissioner Lawrence Gibbs, who said that the tax gap estimates are not intended to be measures of the potential for additional enforcement yields because some would not be ‘cost-effective’ to collect. An economist would substitute the term ‘socially optimal’ for ‘cost-effective,’ but the spirit of Gibbs’s remark is essentially correct. Just as there is an important difference between oil reserves and ‘economically recoverable’ oil reserves, there is a difference between tax evasion and economically (read optimally) recoverable tax evasion.

The normative theory has not yet made much progress in guiding policy regarding the key tools of tax administration, especially the role of information reporting by arms-length parties. The ability of the IRS to rely on reports by firms about wages and salaries paid to employees explains why the (optimal) noncompliance rate of labour income is so much lower than for self-employment income, for which no such information reports exist. The ability to match firm-to-firm sales is touted by advocates as a major administrative advantage of value-added taxes, and the difficulty of monitoring firm-to-consumer sales and to distinguish them from firm-to-firm sales has been noted as the Achilles heel of administering a retail sales tax. Overall, when relatively disinterested third parties can be required to provide information, as they are with wages and salaries, high compliance rates can be achieved at fairly low cost. But when there are only interested parties involved, an alternative mechanism must be found – such as the requirement in an invoice-credit value added tax that taxes on input purchases can be deducted only if the seller produces an invoice for taxes remitted – or else compliance will be low in the absence of costly auditing.

The ubiquity and importance of evasion call into question one of the canons of undergraduate public finance textbooks – that the incidence and efficiency of taxes does not in the long run depend on which side of the market the tax is levied. Once the reality of tax evasion is recognized, the incidence and efficiency of a tax system may depend critically on which side of the market remits the tax to the government and which side must report its transactions to the government. A uniform value-added tax and a uniform national retail sales tax may look identical in a world of no evasion or administrative costs, but have very different effects in the real world.

Tax evasion is widespread, always has been, and probably always will be. Variations in duty and honesty can explain some of the across-individual and, perhaps, across-country heterogeneity of evasion. But the stark differences in compliance rates across taxable items that line up closely with detection rates suggest strongly that deterrence is a powerful factor in evasion decisions. Given the current state of theory and evidence on tax evasion, it is not clear in what way or how much enforcement might be most efficiently increased. Although the normative theory of taxation has been extended to tax system instruments such as the intensity of enforcement, the empirical knowledge for operationalizing these rules is sparse.

Bibliography

IRS (Internal Revenue Service). 2006. Updated estimates of the TY 2001 individual income tax underreporting gap. Overview. 22 February. Washington, DC: Office of Research, Analysis, and Statistics, U.S. Department of the Treasury.

IRS Oversight Board. 2006. 2005 Taxpayer attitude survey. U.S. Department of the Treasury. Online. Available at http://www.ustreas.gov/irsob/releases/2006/02212006.pdf. Accessed 28 June 2007.

Slemrod, J. 2007. Cheating ourselves. Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(1): 25–48.

Slemrod, J., and J. Bakija. 2004. Taxing ourselves: A citizen’s guide to the debate over taxes. 3rd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Slemrod, J., and Yitzhaki, S. 2002. Tax avoidance, evasion and administration. In Handbook of public economics, vol. 3, ed. A. Auerbach and M. Feldstein. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Copyright information

© 2018 Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry

Slemrod, J. (2018). Tax Compliance and Tax Evasion. In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_2771

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_2771

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-95188-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-349-95189-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences