Abstract

The discharge of acid mine drainage from abandoned high sulfur (S) coal mines has caused serious pollution in the Shandi River, Yangquan, Shanxi Province. To determine the impact of long-term acid mine drainage on the microorganisms in the river, we collected river sediments from a polluted tributary (Group P) and the mainstream of Shandi River (Group R) to study the bacterial diversity and community composition. The results showed that the tributary was seriously polluted by acid drainage from abandoned coal mines, with the pH value of the sediment being < 2.5, resulting in the low bacterial richness and diversity of the tributary samples. Acidophillic Fe- and S-metabolizing bacteria, such as Metallibacterium, Acidiphilium, and Acidithiobacillus, were the dominant genera in Group P samples, while the Group R was dominated by the neutral anaerobic iron-reducing bacteria Geothrix and Geobacter. Results of principal co-ordinates analysis (PCoA) revealed that the bacterial communities are significantly different between groups P and R, and the significant different species were mainly attributed to phylum Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Acidobacteria. The distribution of the microbial community is mainly influenced by pH, and the Fe and Cd concentrations. Metallicactrium, the dominant genus, is negatively correlated with pH (R2 = − 0.95) and positively correlated with Fe (R2 = 0.99), while Geothrix and Geobacter, are mainly affected by the heavy metals. This study determined the impact of river pollution caused by abandoned coal mine drainage, especially on the microbial diversity and community composition within the river sediment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Acid mine drainage (AMD) is formed by a series of complex geo-chemical and microbial reactions that occur when sulfide minerals, particularly pyrite (FeS2), are exposed to oxygen and water (Johnson and Hallberg 2005). Although this process occurs naturally, mining operations accelerate the process by increasing the exposure of sulfide minerals to water, oxygen, and microorganisms (Sreethawong et al. 2014). As a result, AMD has become one of the most environmentally threatening by-products of the mining industry (Sun et al. 2015). Acid mine drainage usually contains high concentration of sulfates, iron (Fe), and other heavy metals, and has an acidic pH, which poses a threat to the environment and human health (Akcil and Koldas 2006).

With the increasing depletion of coal reserves, the Chinese government has implemented a series of policies to integrate coal resources, resulting in an increasing number of abandoned coal mines (Chen et al. 2019). The environmental pollution caused by abandoned coal mines, especially AMD cannot be ignored. Acidic pollution caused by abandoned coal mines has been reported in many countries, such as the USA and Korea (Chon et al. 2010; Gammons et al. 2010). This discharged mine water seriously affects the quality of surface water and soil. Many previous studies have focused on AMD from operating coal mines (Yang 2009), coal gangue (Xu et al. 2014, 2017), and metal tailings (Yang et al. 2014). However, the AMD produced by abandoned coal mines, especially underground abandoned coal mines, requires further investigation.

Microorganisms play an important catalytic role in the formation of AMD. A variety of microorganisms are known to be involved in the production of AMD, including Thiobacillus thiooxidans and Thiobacillus ferrooxidans (Baker and Banfield 2003). These microorganisms are carried to the surface environment with the overflow of acidic drainage from abandoned coal mines. At the same time, due to the acidic pH, and high concentrations of sulfates, Fe, and other heavy metals, the discharge of AMD also affects the microbial composition of surface environment. Studies have shown that despite the extreme acidity and toxicity, AMD associated environments harbor numerous microorganisms (David 2012; Hallberg 2010). A variety of acidophilic and metal tolerant microorganisms have been identified in AMD environments (Baker and Banfield 2003). Previous studies of the diversity of microorganisms in AMD with an extremely low pH (< 2) have shown that acidophilic bacteria mainly include a group of sulfur (S) and/or Fe-oxidizers, that can be classified into Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans, Leptospirillum ferrooxidans, and Ferroplasma spp. (Guo et al. 2013). Microaerobes, facultative anaerobes, and obligatory anaerobes, including Acidithiobacillus, Sulfobacillus, Thiomonas, Gallionella, Geobacter, Geothrix, and Clostridium were found to be the main bacteria in river sediment in the vicinity of Dabaoshan multimetallic mine (Bao et al. 2017). The impact of long-term AMD from abandoned coal mines on microbial communities in river sediments under different pollution levels requires further study.

In the Shandi River Basin, Yangquan, acid drainage from abandoned coal mines has flowed directly into the river without any treatment. Long-term drainage of mine water has resulted in a large amount of yellow sediment being deposited on the river bed. To determine the impact of acid drainage on the microorganisms in the river, we collected river sediments from a polluted tributary and the mainstream of Shandi River to study the bacterial diversity and community composition by Illumina MiSeq sequencing (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection

In September 2018, sediment samples were collected from seven locations in the Shandi River, Yangquan, Shanxi Province. As shown in Fig. 1, samples P1–P4 were collected from a tributary contaminated by abandoned coal mine drainage, and RQ, RM, and RQ were collected from the mainstream of Shandi River. The sample RQ was river sediment before the confluence of the polluted tributary. To ensure that the sediment samples fully reflected the impact of the polluted tributary inflow on the Shandi River, we collected sample (RM) at 100 m downstream of the tributary confluence. The RQ site was located 1 km downstream of the confluence point. At each sampling site, we collected four subsamples at the same time (Chang et al. 2004), with a distance of >5 m between each point. All the samples from each site were manually pooled into one sample, with sufficient mixing to achieve visual homogeneity (Yuan et al. 2002). The pooled samples were placed in sterile boxes and transported to the laboratory. After mixing, each sediment sample was divided into two parts. One part was stored at 4 °C for physical and chemical analyses, while the second part was stored at − 80 °C until DNA extraction.

2.2 Physicochemical analysis of samples

For physicochemical analyses, solid samples were dried in a freeze dryer (FD-1A-50, BioCool, Beijing, China) and thoroughly ground using a pestle and mortar. To measure pH in the sediments, 10 g of dry solid sample was passed through a 2-mm mesh and mixed with 25 mL of distilled water (1:2.5 (m/v)). The mixture was left to equilibrate for 30 min after shaking for 2 min and then measured using a calibrated pH meter (PXSJ-216F, Rex, Shanghai, China) according to the methods of the People’s Republic of China National Environmental Protection Standard (HJ962-2018). Samples with pH < 7 were tested with KCl solution (1 mol/L) instead of distilled water according to the standard (LY/T 1239-1999). The total Fe in solid samples was measured according to a method reported by Sun et al. (2018). Extractions were performed using 1.0 M HCl for 30 min at room temperature, and then the total Fe was measured spectrophotometrically at 510 nm with 1,10 phenanthroline (722, Sunny Hengping, Shanghai, China). To determine the heavy metal concentrations in sediments, 0.2 g dry solid samples were passed through a 0.15-mm mesh and microwave digested in a digestion tank with 1 mL HCl, 4 mL HNO3, 1 mL HF, and 1 mL H2O2. They were then analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICAP-QC, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the Chinese standard (HJ 766-2015).

2.3 DNA Extraction, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, and Illumina MiSeq sequencing

Total soil DNA was extracted from 1.0 g samples using an E.Z.N.A.® soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The extracted DNA concentration and quality were estimated using a Nanodrop® ND-2000 UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Amplicon libraries were produced using the bacteria-universal primers 338F and 806R, which were designed for the V3–V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene (Lee et al. 2012). The PCR conditions were as follows: 3 min at 95 °C, followed by 29 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 30 s for annealing at 55 °C, and 45 s for elongation at 72 °C, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min, and 10 °C until halted by the user. The PCR reactions were performed in triplicate in a final volume of 20 μL, using a mixture containing 4 μL of × 5 FastPfu Buffer, 2 μL of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.8 μL of forward primer (5 μM), 0.8 μL of reverse primer (5 μM), 0.4 μL of FastPfu polymerase, 10 ng of template DNA, and 0.2 μL of BSA. The resulting PCR products were extracted from a 2% agarose gel and further purified using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA) and quantified using QuantiFluor™-ST (Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Wang et al. 2018). Purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar concentrations and sequenced (300 bp paired) on an Illumina MiSeq platform according to the standard protocols issued by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.4 Sequence processing and statistical analyses

Sequences from the Illumina MiSeq platform were processed using the QIIME (version 1.70) software package (Campbell et al. 2010). Raw fastq files were demultiplexed, quality filtered by Trimmomatic, and merged by FLASH (Mago and Salzberg 2011), with the following criteria. (1) The reads were truncated at any site receiving an average quality score < 20 over a 50 bp sliding window. (2) Primers were exactly matched allowing two nucleotides, while mismatching primers and reads containing ambiguous bases were removed. (3) Sequences with an overlap longer than 10 bp were merged according to their overlap sequence (Chen et al. 2018). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered with 97% similarity cutoff using Usearch (version 7.0). The taxonomy of each 16S rRNA gene sequence was analyzed by a Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) classifier algorithm (version 2.2) against the Silva 16S rRNA database using a confidence threshold of 70% (Elmar et al. 2007).

The rarefaction curves were calculated using the mothur (v 1.30.1) software (Schloss et al. 2009). Bacterial community diversity was estimated using the number of OTUs (Sobs), Chao1 (Chao 1984), and Shannon indices. A beta diversity analysis was performed using the Bray–Curtis distance algorithm to compare the results of a principal co-ordinates analysis (PCoA) using the community ecology package, R (Mitter et al. 2017). A Mantel test was performed and a heatmap was produced using the Qiime and pheatmap packages in R, respectively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Sequencing results and bacterial diversity

Following a quality control procedure, and the removal of chimeras and non-targeted sequences, a total of 405,008 high quality sequences, with an average length of 438 bp were obtained from the sediment samples and used for further analysis. To avoid the influence of the individual differences of each sample, the initial sequences of each sample were uniformed according to the minimum sequence number. After subsampling each sample to an equal sequencing depth (28295 reads per sample) and clustering, 2043 OTUs at the 97% identity threshold were obtained, with the number of OTUs ranging from 280 to 1446 per community (Table 1). The good coverage values (all > 99%) suggested that the 28,295 sequences for each sample were sufficient to characterize the bacterial communities in the samples (Table 1). The rarefaction curves produced a similar result and showed that the number of OTUs increased with the number of sequences obtained in each of the soil samples (Fig. 2). The pH values of the tributary sediment (Group P) were all below 2.5, with the average Fe concentration being 811.75 g/kg (Table 2), which together indicated that the tributary was seriously polluted by acid drainage from abandoned coal mines.

The number of OTUs obtained from the samples ranged from 280 to 1446, with P4 having the minimum value and RH having the maximum. There was a significant difference in the number of OTUs obtained between the two groups (Fig. 2). The average number of OTUs obtained from Group R (1367) was nearly 3.46 times higher than that of Group P (395). The average Chao1 and Shannon index values of Group P were 470 and 4.00, respectively, while for Group R they were 1508 and 6.05, respectively. The results of the statistical analysis indicated that there were significant differences between Group P and Group R in all alpha diversity indices (p < 0.001), which may be related to the differences in physicochemical properties. The Pearson correlation analysis showed that the OTU number, and Chao1 and Shannon index values of samples were positively related to the pH value, with R2 values of 0.978 (OTUs), 0.970 (Chao1), and 0.973 (Shannon) and negatively related to the Fe concentration, with R2 values of − 0.990 (OTUs), − 0.986 (Chao1), and − 0.995 (Shannon), respectively. This may be due to the extreme oligotrophic environment, with a high Fe concentration and low pH, which led to a decrease in bacterial diversity and richness (Zhang 2015).

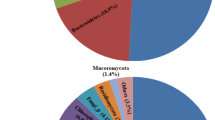

3.2 Bacterial taxonomy composition of samples

The 2043 OTUs after clustering could be assigned into 43 different phyla. The dominant phyla in samples were Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Acidobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Bacteroidetes (Fig. 3), which totally accounted for 85.24%–95.53% of all sequences. Proteobacteria was the most widely distributed phylum in all samples, with the relative abundance ranging from 32.93% to 57.69%. This was comparable to previous results reported for AMD polluted areas, in which the Proteobacteria accounted for 38%–72% (Sun et al. 2015). The proportion of Actinobacteria in the Group P samples was higher than that in Group R. For example, the proportion of Actinobacteria in P1 was 23.74%, while in RM it was only 6.31%. There was no significant difference in the distribution of Firmicutes between the two groups, and the average proportion was approximately 10%. The distribution of Chloroflexi was quite different among the samples, with a relative abundance of 15.94% in sample P3 but only 2.57% in sample P1. The relative abundance of Bacteroidetes in RQ, RM, and RH were 11.88%, 9.46%, and 7.26%, respectively, while its proportional distribution in Group P samples was lower than 0.01%. Bacteroidetes was the common dominant phylum in river sediments (Liu et al. 2018), and its distribution was greatly affected by the pH value (Guo 2016). Therefore, the lower relative abundance of Bacteroidetes in group P may attribute to the lower pH value (1.9–2.2) of the contaminated tributary sediment.

The distribution of bacteria at the genus level is shown in Fig. 4 (genera with a relative abundance < 5% were classified into others). Metallibacterium, Acidiphilium, Acidithiobacillus, Acidibacter, and Acidothermus were the dominant genera in Group P, with an average relative abundance of 18.80%, 5.08%, 5.03%, 4.73%, and 3.38%, respectively. Metallibacterium had the highest relative abundance in Group P, with relative abundances in P1–P4 of 25%, 14%, 15%, and 26%, respectively. Metallibacterium is comprised of acidophilic microorganisms capable of heterotrophic or lithotrophic Fe(III) reduction (Brantner and Senko 2014; Ziegler et al. 2013). In many recent studies, Metallibacterium populations have been detected in high-Fe environments (Brantner et al. 2014; Brantner and Senko 2014). These observations may be attributed to their metabolic capability for Fe reduction. Geothrix and Geobacter were the dominant genera in Group R. Geothrix was the genus with the highest relative abundance in Group R, with abundances of 23%, 14%, and 15% in RQ, RH, and RM, respectively. Both Geobacter and Geothrix were reported to be neutrophilic Fe(III)-reducing bacteria in previous studies (Islam et al. 2005), and therefore had a high relative abundance in the neutral river samples.

3.3 Comparison of the distribution of bacteria in the different groups

The differences between samples were analyzed by a principal co-ordinates analysis (PCoA) at OTU level using the Bray–Curtis distance algorithm (Fig. 5). The algorithm is based on the Euclidean distance, which can be used to express the differences in absolute abundance between samples. In the PCoA analysis chart, the explanations of the PC1 and PC2 axes for the ranking results were 63.84% and 11.68%, respectively, which shows that these two main components were representative. It can be seen from Fig. 5 that samples from the polluted tributary were mainly distributed on the right side, while samples from the mainstream of the river were mainly distributed on the left side, indicating that the relative abundance of bacteria between these two groups was quite significant. Compared with Group R, the samples in Group P were more clustered, indicating that the differences between the samples were smaller. The distance between sample points in the PCoA chart can be used to judge the similarity and difference between samples. It can be seen that the distance between the RM and Group P samples was less than that for the RQ and RH samples, which may be due to the inflow of pollution from the tributary, resulting in a change in the microbial community in river sediment.

Figure 5 shows that there were significant differences between Group P and Group R. To identify the differences between bacteria, a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the bacterial communities of the two groups. The thirty top OTUs with significant differences between the two groups are shown in Fig. 6 (p < 0.05). These OTUs were mainly distributed in the dominant phyla, among which 13 belonged to Proteobacteria, five belonged to Actinobacteria, two belonged to Firmicutes, and six belonged to Acidobacteria.

The OTUs with a high relative abundance (> 1%) in Group P included OTU1711 (3.84%), OTU1951 (3.16%), OTU1916 (2.38%), OTU1902 (1.36%) and OTU 2033 (1.24%). Among them, OTU1711 belongs to the unclassified bacteria of Proteobacteria, and the OTU1951, OTU1916, OTU1902 and OTU2033 can be classified to Acidothermus, Acidibacter, Acidithrix and Ferrithrix, respectively. Acidothermus, discovering in acidic hot spring, is classified as a kind of thermophilic, acidophilic, and cellulolytic bacteria (Winter et al. 2012). Acidibacter is an acidophilic ferric reducing gammaproteobacterium, belonging to moderate acidophile bacteria (Falagán and Johnson 2014). Acidithrix was isolated from an acidic draining stream of an abandoned copper mine, and it can catalyze the oxidation of ferrous (but not the oxidation of S or hydrogen (H)) under aerobic conditions, and the reduction of ferric under micro-aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Jones and Johnson 2015). Ferrithrix is a heterotrophic, Fe-oxidizing, and extremely acidophilic actinobacteria (Johnson et al. 2009). Most of the microorganisms with significant differences in group P were acidophilic Fe metabolizers. This may be because the extremely acidic (pH 1.9–2.1) and high Fe environment of the polluted tributary inhibited the growth of most microorganisms, enabling the acidophilic Fe-metabolizing bacteria to become the dominant genera.

The OTUs with high relative abundance (> 1%) in Group R included Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 (OTU874, 1.77%), Geothrix (OTU16, 1.87%), OTU30 (1.27%), Aquabacterium (OTU1625, 1.37%), Geobacter (OTU458, 1.24%), and Anaeromyxobacter (OTU189, 1.22%). Among them, Geothrix and Geobacter are known to be neutrophilic Fe(III)-reducing bacteria (Islam et al. 2005). Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 is widely distributed in the natural environment, and most of them are anaerobic or slightly aerobic bacteria (Luo et al. 2019). Anaeromyxobacter can grow under both oxic and anoxic redox conditions, which can realize the reduction of Fe(III) (Qiang and Sanford 2003). Aquabacterium display a microaerophilic growth behavior and can use oxygen and nitrate as electron acceptors (Lin et al. 2009). In Group R, most of the microorganisms with significant differences were anaerobic or microaerophilic, which may be due to the anaerobic environment of the river sediment, providing suitable living conditions for anaerobic microorganisms. In addition, these bacteria can participate in Fe metabolism and reduce Fe under anaerobic or anoxic conditions, which may be due to the high Fe concentration in Group R sediment (average 301.33 g/kg).

3.4 Correlation between community structure and environmental factors

A Mantel test was conducted to analyze the correlations between environmental factors and the distribution of the bacterial community in the samples. The results showed that the bacterial community was significantly correlated with the pH (R2 = 0.978, p < 0.01), Fe (R2 = 0.968, p < 0.01), and Cd (R2 = 0.842, p < 0.01). The Spearman correlations between the main genera and environmental factors in sediment samples is shown in Fig. 7. The distribution of the Fe-reducing bacteria Metallibacterium was significantly negatively correlated with pH (R2 = − 0.95) and positively correlated with the Fe concentration (R2 = 0.99). The acidophilic bacteria Acidiphilium, Acidicapsa, Acidithrix, Acidothermus, and Ferrovum had the same distribution characteristics as Metallicactrium. The distribution of these acidophilic bacteria was strongly correlated with the pH and Fe concentration. However, Geothrix and Geobacter, the dominant bacteria in Group R, displayed the opposite distributional characteristics to these acidophilic bacteria, i.e., a positive correlation with pH and a negative correlation with the Fe concentration. This was mainly because Geothrix and Geobacter are bacteria that thrive in neutral conditions and are unlikely to survive in an acid environment (Islam et al. 2005). Figure 7 shows that the distribution of Geothrix and Geobacter were positively correlated with the heavy metal concentrations. This was mainly due to the strong metal resistance of Geothrix and Geobacter (Burkhardt et al. 2011).

3.5 Distribution of microorganisms along the mainstream of Shandi River

To determine the influence of acid drainage from abandoned coal mines on the microbial community of Shandi River sediment, we conducted a comparative analysis of the sediment along the river. The pH of the mainstream sediment decreased from 6.7 (RQ) to 4.9 (RM) after the acid drainage from the abandoned coal mine entered into the Shandi River, and the Fe concentration increased from 253 g/kg (RQ) to 365 g/kg (RM). Compared with RQ, the pH (6.3) of RH was lower, and the Fe concentration (286 g/kg) was higher (Table 2). The numbers of OTUs in river samples were 1398 (RQ), 1257 (RM), and 1446 (RH). The Shannon index displayed the same trend as the OTUs, i.e., the number of OTUs and Shannon index initially decreased after the inflow of the polluted tributary, and then increased gradually with the water migration. The number of OTUs and Shannon index of the downstream sample (RH) were higher than that of the upstream sample (RQ).

The distribution of microbial communities along the mainstream of Shandi River is shown in Fig. 8. The phyla and genera with an average abundance of > 2% were defined as dominant. Compared with RM and RQ, the dominant phyla with a significant increase in relative abundance included Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Parcubacteria (p < 0.001), while the dominant phyla with a significant decrease included Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Spirochaetae (p < 0.001). The relative abundance of Acidobacteria did not change significantly. Compared with RH and RQ, the dominant phylum with a significant increase in relative abundance included Proteobacteria, Spirochaetae, and Parcubacteria (p < 0.001), and the other dominant phylum decreased significantly (p < 0.001). The relative abundance of norank_f_Spirochaetaceae, Rhodanobacter, and Anaeromyxobacter in RM and RH increased significantly due to the introduction of polluted tributaries (p < 0.001). There was no significant difference between the relative abundance of Geothrix and Geobacter in RM and RQ. However, the relative abundance of Geothrix decreased significantly, while that of Geobacter increased significantly in the downstream sample (RH). In conclusion, the inflow of the polluted tributary significantly changed the microbial community in the river sediment. Although the pH of the downstream sample (RH) increased to become almost neutral (pH = 6.3), the microbial community in the sediment still changed substantially.

4 Conclusions

The discharge of acid drainage from abandoned high surfur(S) coal mines has caused serious pollution in Shandi River, Yangquan, Shanxi Province. In this study, river sediment samples from a polluted tributary and the mainstream of Shandi River were collected to study the bacterial diversity and community composition by high throughput Illumina MiSeq sequencing.

The results showed that the tributary was seriously polluted by AMD, resulting in a significant decrease of the richness and diversity of bacteria (p < 0.001). Acidophillic Fe- and S-metabolizing bacteria, such as Metallibacterium, Acidiphilium, and Acidithiobacillus were the dominant genera in the polluted tributary sediment, while the neutral anaerobic Fe-reducing bacteria Geothrix and Geobacter were the dominant genera in the mainstream sediment. The PCoA analysis showed that there were significant differences in bacterial communities between the polluted tributary and mainstream sediment samples. The bacteria with significant differences were mainly distributed in the Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Acidobacteria. The Mantel test results showed that the pH, and Fe and Cd concentrations had a significant influence on the distribution of the microbial community. Metallicactrium, the dominant genus in group P, was negatively correlated with pH and positively correlated with the Fe concentration, while the dominant genera of Group R, Geothrix and Geobacter, were greatly affected by the heavy metal concentrations. The distribution of microorganisms in the mainstream sediment indicated that the inflow of acid drainage from abandoned coal mines significantly changed the microbial community structure of river sediments.

This study highlighted the impact of long-term AMD from abandoned coal mines on the microbial community structure of river sediments. Some genera had a close relationship with heavy metals, which may provide a new way for the natural bioremediation of polluted area.

References

Akcil A, Koldas S (2006) Acid mine drainage (AMD): causes, treatment and case studies. J Clean Prod 14(12–13):1139–1145

Baker BJ, Banfield JF (2003) Microbial communities in acid mine drainage. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 44:139–152

Bao Y, Guo C, Wang H, Lu G, Yang C, Chen M, Dang Z (2017) Fe- and S-metabolizing microbial communities dominate an AMD-contaminated river ecosystem and play important roles in Fe and S cycling. Geomicrobiol J 34(8):695–705

Brantner JS, Senko JM (2014) Response of soil-associated microbial communities to intrusion of coal mine-derived acid mine drainage. Environ Sci Technol 48:8556–8563

Brantner JS, Haake ZJ, Burwick JE, Menge CM, Hotchkiss ST, Senko JM (2014) Depth-dependent geochemical and microbiological gradients in Fe(III) deposits resulting from coal mine-derived acid mine drainage. Front Microbiol 5:215

Burkhardt EM, Bischoff S, Akob DM, Büchel G, Küsel K (2011) Heavy metal tolerance of Fe(III)-reducing microbial communities in contaminated creek bank soils. Appl Environ Microbiol 77(9):3132–3136

Campbell BJ, Polson SW, Hanson TE, Mack MC, Schuur EA (2010) The effect of nutrient deposition on bacterial communities in Arctic tundra soil. Environ Microbiol 12:1842–1854

Chang B, Yu C, Yuan S (2004) Degradation of nonylphenol by anaerobic microorganisms from river sediment. Chemosphere 55:493–500

Chao A (1984) Nonparametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand J Stat 11:265–270

Chen W, Teng Y, Li Z, Liu W, Ren W, Luo Y, Cheixtie P (2018) Mechanisms by which organic fertilizer and effective microbes mitigate peanut continuous cropping yield constraints in a red soil of south China. Appl Soil Ecol 128:23–34

Chen D, Feng Q, Liang H, Gao B, Alam E (2019) Distribution characteristics and ecological risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in underground coal mining environment of Xuzhou. Hum Ecol Risk Assess Int J 25(6):1564–1578

Chon HT, Kim JY, Choi SY (2010) Hydrogeochemical characteristics of acid mine drainage around the abandoned Youngdong coal mine in Korea. Resour Geol 49:113–120

David BJ (2012) Geomicrobiology of extremely acidic subsurface environments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 81:2–12

Elmar P, Christian Q, Katrin K, Fuchs BM, Wolfgang L, Rg J, P, Frank Oliver G C, (2007) SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 35(21):7188–7196

Falagán C, Johnson DB (2014) Acidibacter ferrireducens gen. nov., sp. nov.: an acidophilic ferric iron-reducing gammaproteobacterium. Extremophiles 18:1067–1073

Gammons CH, Duaime TE, Parker SR, Poulson SR, Kennelly P (2010) Geochemistry and stable isotope investigation of acid mine drainage associated with abandoned coal mines in central Montana, USA. Chem Geol 269(1–2):112

Guo W (2016) The microbial mechanism of effects of reclaimed water irrigation on nitrogen biological effectiveness. Doctor’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences Dissertation

Guo Y, Huang P, Zhang W, Yuan X, Fan F, Wang H, Liu J, Wang Z (2013) Leaching of heavy metals from Dexing copper mine tailings pond. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China 23(10):3068–3075

Hallberg KB (2010) New perspectives in acid mine drainage microbiology. Hydrometallurgy 104:448–453

Islam FS, Boothman C, Gault AG, Polya DA, Lloyd JR (2005) Potential role of the Fe(III)-reducing bacteria Geobacter and Geothrix in controlling arsenic solubility in Bengal delta sediments. Miner Mag 69:865–875

Johnson DB, Hallberg KB (2005) Acid mine drainage remediation options: a review. Sci Total Environ 338:3–14

Johnson DB, Bacelar NP, Okibe N, Thomas A, Hallberg KB (2009) Ferrimicrobium acidiphilum gen. nov., sp. nov. and Ferrithrix thermotolerans gen. nov., sp. nov.: heterotrophic, iron-oxidizing, extremely acidophilic actinobacteria. Int J System Evolut Microbiol 59: 1082

Jones RM, Johnson DB (2015) Acidithrix ferrooxidans gen. nov., sp. nov.; a filamentous and obligately heterotrophic, acidophilic member of the Actinobacteria that catalyzes dissimilatory oxido-reduction of iron. Res Microbiol 166(2): 111–120

Lee CK, Barbier BA, Bottos EM, McDonald IR, Cary SC (2012) The inter-valley soil comparative survey: the ecology of Dry Valley edaphic microbial communities. ISME J 6(5):1046–1057

Lin M, Jiang S, Chou J (2009) Aquabacterium fontiphilum sp. nov., isolated from spring water. Int J System Evolut Microbiol 59(4): 681–685

Liu Z, Wang P, Xiao H, Chen B (2018) Characteristics of aquatic bacterial community and the influencing factors in an urban river—a case study of Nanchang section of the Ganjiang River, Lake Poyang Basin. J Lake Sci 30(3):741–752

Luo X, Zhang W, Yuan L, Xu M, He L, Jiang Y, Zhong W, Zhang Y (2019) Correlation between resistance genes and microbial community in polluted rivers. China Environ Sci 39(6):2606–2613

Mago T, Salzberg SL (2011) FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27:2957

Mitter EK, Freitas JR, Germida JJ (2017) Bacterial root microbiome of plants growing in oil sands reclamation covers. Front Microbiol 8:849

Qiang H, Sanford RA (2003) Characterization of Fe(III) reduction by chlororespiring Anaeromyxobacter dehalogenans. Appl Environ Microbiol 69(5):2712–2718

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ (2009) Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75(23):7537–7541

Sreethawong T, Ngamsinlapasathian S, Yoshikawa S (2014) Acid mine drainage: challenges and opportunities. J Environ Chem Eng 2(3):1785–1803

Sun W, Xiao T, Sun M, Dong Y, Ning Z, Xiao E, Tang S, Li J (2015) Diversity of the sediment microbial community in the Aha Watershed (Southwest China) in response to acid mine drainage pollution gradients. Appl Environ Microbiol 81(15):4874–4884

Sun W, Xiao E, Pu Z, Krumins V, Dong Y, Li B, Hu M (2018) Paddy soil microbial communities driven by environment– and microbe–microbe interactions: a case study of elevation-resolved microbial communities in a rice terrace. Sci Total Environ 612:884–893

Wang Y, Wang C, Zhou W, Yang FY, Chen XX, Zhang Q (2018) Effects of Wilting and Lactobacillus plantarum addition on the fermentation quality and microbial community of Moringa oleifera leaf Silage. Front Microbiol 9:1817

Winter RT, Heuts DPHM, Rijpkema EMA, Bloois EV, Wijma HJ, Fraaije MW (2012) Hot or not? Discovery and characterization of a thermostable alditol oxidase from Acidothermus cellulolyticus 11B. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 95(2):389–403

Xu J, Hu Z, Zhao Y, Wei B (2014) The bactericide of Acidithiobacillus ferroxidans in acid coal waste piles. China Min Mag 1:62–65

Xu J, Zhang J, Cui S, Zhang P (2017) Research progress in pollution control technologies of acidic wastewater from coal gangue. China Min Mag 1:43–48

Yang PM (2009) Status and progress of research on acid mine water treatment and utilization in coal mine. Sci Technol Innov Herald 01:125

Yang Y, Li Y, Sun Q (2014) Archaeal and bacterial communities in acid mine drainage from metal-rich abandoned tailing ponds, Tongling, China. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China 24(10):3332–3342

Yuan S, Liu C, Liao C, Chang B (2002) Occurrence and microbial degradation of phthalate esters in Taiwan river sediments. Chemosphere 49(10):1295–1299

Zhang GY (2015) Microbial diversity in soils (iron–manganese nodules) from several habitats. Doctor’s Thesis, Huazhong Agricultural University

Zheng Z, Cai CF (2007) Research progress on formation mechanism of acid mine drainage in coal mine. Resour Environ Eng 3:323–327

Ziegler S, Waidner B, Itoh T, Schumann P, Spring S, Gescher J (2013) Metallibacterium scheffleri gen. nov., sp. nov., an alkalinizing gammaproteobacterium isolated from an acidic biofilm. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 63:1499–1504

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41977159).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Feng, Q., Li, W. et al. Effects of acid drainage from abandoned coal mines on the microbial community of Shandi River sediment, Shanxi Province. Int J Coal Sci Technol 8, 756–766 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-021-00433-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-021-00433-5