Abstract

Suicide is a major cause of death in American youth. Suicide risk assessment is a promising suicide prevention strategy; however, little is known about school-based suicide risk assessment practices. The purpose of this study was to examine the scope of standardization, comprehensiveness, and follow-up procedures as part of the suicide risk assessment (SRA) process in use among school-based mental health professionals in Colorado. Participants were 72 school psychologists, school counselors, and school social workers employed in school districts across the state. Results indicate the reported ability of SRA procedures to identify imminent suicide risk was strong in relation to other aspects of suicide risk. The analysis of SRA alignment with the interpersonal theory of suicide model revealed that SRA procedures currently in place are significantly more helpful at investigating aspects of acquired capability in comparison to thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Respondents were significantly less likely to agree with statements about the ability of SRA procedures to support re-entry and follow-up compared with statements about risk identification and treatment decision-making. The results of this survey suggest that school-based mental health professionals need increased support in developing school re-entry and follow-up procedures to monitor suicide risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

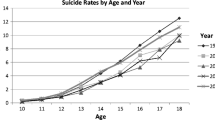

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates nationwide suicide rates increased 35% between 1999 and 2018 (Hedegaard et al., 2020), and it is currently the second leading cause of death for people in the USA aged 5–24 years. In Colorado, suicide is the leading cause of death among youth ages 10–18 (CDC, 2018). Clearly, suicide is a major public health problem in Colorado and across the country.

In addition to deaths by suicide, there is evidence that youth experience a range of non-fatal suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) is a nationwide initiative which monitors health-related behaviors among youth and young adults. The 2019 YRBSS report includes the results of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), administered across 44 states and 28 school districts. Nationwide, 18.8% of the 13,677 high school students who responded to the 2019 YRBS questionnaires disclosed they had seriously considered attempting suicide during the past 12 months, and 8.9% of high school students nationwide reported a suicide attempt (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020). The prevalence of suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts in Colorado is similar to national data (CDC, n.d.). However, Colorado appears to be disproportionately impacted by suicide, as the state saw suicide rates in teens increase 58% between 2016 and 2019 (United Health Foundation, 2020), and as noted above, suicide is the leading cause of death in Colorado youth (CDC, 2018).

Interpersonal Theory of Suicide

The interpersonal theory of suicide (ITS) proposes that predisposing stressors of thwarted belongingness (difficulty establishing and maintaining close relationships with others) and perceived burdensomeness (feeling that one is a burden on others and would be better off dead) give rise to suicidal ideation and substantially increase the risk for suicidal behavior (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). A third and independent factor is the individual’s acquired capability for self-harm which emerges via habituation to previous self-inflicted injury, prior suicide attempts, and experiences of abuse (Van Orden et al., 2010). Effectively, acquired capability occurs when one becomes inured to fear of death or injury via repeated exposure to harmful events, whether self-inflicted or otherwise (Joiner, 2010). The clinical presentation of acquired capability may reflect a lowered fear of death, elevated physical pain tolerance, habituation to pain and elevated opponent processes such as exhilaration, and/or exposure to trauma such as childhood maltreatment and previous suicide attempts (Van Orden et al., 2010). According to the ITS, suicidal ideation arises when thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness co-occur, but individuals will not act on thoughts of suicide without the acquired capability for self-harm (Chu et al., 2016; Van Orden et al., 2010).

Empirical support for ITS as a tool for identifying suicide risk has emerged across a wide range of clinical samples, including adolescents, adults, and military veterans (Chu et al., 2016). In a study with young adults, Joiner et al. (2009b) found that for those who endorsed symptoms of major depression, low levels of thwarted belongingness and high levels of perceived burdensomeness were associated with suicidal ideation. Analyses indicated a three-way interaction between thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability to be significantly predictive of whether a suicidal crisis would involve a suicide attempt versus suicidal ideation (Joiner et al., 2009a). Similarly, high levels of acquired capability were significantly predictive of a suicide attempt within 12 months following hospitalization in a sample of psychiatric adolescent inpatients (Czyz et al., 2015). Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) was also identified by Franklin et al. (2011) as a factor which contributes to suicide risk among young adults due to the role of NSSI as a provocative event which increases the acquired capability for suicidal behavior. Lifetime history of suicidal behavior and NSSI were also found to be significant predictors of a suicide attempt in a prospective study of adolescents (King et al., 2019).

Risk Factors for Suicide

A history of past suicide attempts, particularly violent or medically serious suicide attempts, is among the most powerful risk factors for suicide (Forman et al., 2004; Miranda et al., 2008). Such a history is a more powerful predictor of suicide risk than the existence of psychiatric disorders, including depression (Hom et al., 2016). According to Joiner (2005), a history of multiple suicide attempts builds the acquired capability for more serious suicidal behavior in the future. This aspect of the ITS is corroborated by an analysis of individuals with a history of multiple suicide attempts which found that such individuals showed increased levels of planning, higher lethality of intent, and increased feelings of regret over recovering from a suicide attempt (Kaslow et al., 2006).

In addition to a history of attempts, a variety of other factors that contribute to the development of suicidal ideation and attempts have been identified. These include psychological distress, psychiatric comorbidity, intent to die, substance abuse, aggression, maladaptive coping skills, a belief in the acceptability of suicide, low levels of family adaptability and cohesion, relationship discord, family violence, poor interpersonal conflict resolution skills, and a history of physical or sexual abuse (Anglin et al., 2005; Kaslow et al., 2006; Nock and Kessler, 2006; Thompson et al., 2002). An additional risk factor for suicidal thoughts and behaviors that has received a great deal of attention in the media is bullying. Youth who experience bullying and/or cyberbullying have reported significantly higher rates of suicide ideation (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010) and suicide attempts (Crepeau-Hobson & Leech, 2016). Sexual orientation also appears to impact the prevalence of suicidal behavior, as gay, lesbian, and bisexual (LGB) youth report higher rates of suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts than heterosexual peers (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020). Gender minority youth, such as youth who are transgender or gender non-conforming, also report higher levels of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts than their gender-conforming peers (Eisenberg et al., 2017; McKay et al., 2019). The intersecting identities of minoritized race/ethnicity and LGB status are also associated with increased risk with non-White sexual minority adolescents being more likely to report a suicide attempt than those who identify as White (Baiden et al., 2020).

Protective Factors for Suicide

In addition to risk factors, a variety of factors that may protect against or modulate the expression of suicidal behavior have been identified. Collectively, previous research suggests that a positive school climate, strong teacher–student relationships, strong family support, and school connectedness via prosocial clubs and activities with similar peers are protective factors against psychosocial distress and suicidal behaviors (Benbenishty et al., 2018; Joiner et al., 2009a; Madjar et al., 2018; Sulkowski & Simmons, 2018; Williams et al., 2018). School or social connectedness appears to be an especially powerful protective factor for high-risk adolescents and sexual minority youth in particular (Marraccini and Brier, 2017).

Warning Signs of Suicide

While risk factors are those variables that increase the likelihood of suicide, warning signs are indicators that the risk has been realized. Warning signs that suggest near-term suicidal risk include verbal threats such as “I am going to kill myself,” sudden behavior changes, changes in school performance, social isolation, and preoccupation with themes of death and dying (King, 2006). Research has indicated that NSSI is another important risk factor that differentiates youth who attempted suicide from those who only considered suicide and those with no suicidal ideation (Taliaferror & Muehlenkamp, 2013). The relationship between NSSI and suicidal behavior has been found even after accounting for known risk factors (Borowsky et al., 2013; Hamza et al., 2012). These findings align with the function of acquired capability posited by Joiner et al. (2009a), indicating that the presence of self-harming behavior merits clinical attention as a warning sign which may enhance near-term suicidal risk. Stressful life events such as serious illness, changes in close relationships, or death of a loved one also bear consideration as warning signs in combination with verbal threats and behavioral factors (King & Vidourek, 2012). Most youth who contemplate suicide do exhibit warning signs or communicate their suicidal intent to others (King & Vidourek, 2012).

Suicide Risk Assessment

Early detection and intervention are critical to preventing suicide. As such, school-based suicide prevention efforts must include processes for identifying and responding to students who are contemplating lethal self-harm. One such promising strategy is suicide risk assessment (SRA) (Beautrais, 2005; Crepeau-Hobson, 2013). Based on what is known about suicide risk and warning signs, SRA is intended to determine if an individual is suicidal and if so, to what extent. SRAs typically involve an interview with the student of concern and assess risk and protective factors, strengths, current stressors, and precipitating factors (Crepeau-Hobson, 2013). These data are then used to guide the treatment of those identified as at risk for suicide (Gutierrez et al., 2019). Although research examining the use of SRA in school settings is extremely limited, there is evidence that the use of SRA can promote suicide prevention, reduction in suicidal ideation, and reduction in suicide attempts (Beautrais, 2005; Bryan et al., 2017). According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (2018), school-based suicide assessments are crucial for identifying and intervening with at-risk students.

Given the alarming youth suicide rates in Colorado, suicide prevention, including the use of SRA, clearly should be a priority in the state. However, the limited available literature base indicates that SRA procedures among school-based mental health professionals in Colorado may not be implemented in a standardized or consistent fashion (Crepeau-Hobson, 2013). Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to examine the scope of standardization, comprehensiveness, and follow-up procedures as part of the SRA process in use among school-based mental health professionals in Colorado.

Given the strong empirical support for conceptualizing youth suicide risk via the ITS model (Barzilay et al., 2019), this study also investigated the alignment of school-based SRA procedures with ITS components of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability, something no previous study has sought to analyze. Specifically, this study aimed to answer the following research questions: (1) to what extent do school-based mental health professionals in Colorado utilize standardized screening tools and interview protocols as part of the SRA process?; (2) how do these school-based mental health professionals rate the comprehensiveness of the SRA process in use at their job site?; (3) what follow-up procedures are in place to support the SRA process in school settings?; and (4) do SRA procedures in use among school-based mental health professionals in Colorado align with ITS components of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability?

Method

Participants and Procedure

Potential respondents were sent an informed consent form and a link to the survey via email. The emails were sent to the member listservs of the Colorado Society of School Psychologists and the Colorado School Social Work Association. The email was also disseminated by mental health directors for several school districts in Colorado and sent to recent graduates of a local school psychology doctoral program on an individual basis. The email was sent to a total of 348 individuals.

Seventy-two (72) school-based mental health professionals across 17 Colorado school districts completed the survey (response rate = 20.7%). Seven additional surveys were not included in the analyses due to missing data. A majority of respondents were school psychologists (65%), and 52% had at least 5 years of experience. Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of participants.

Measure

The survey was developed for this study based on what is known about nest practices in school-based suicide risk assessment. It was reviewed by an experienced suicide researcher and an expert in survey design prior to dissemination. The survey was administered via Qualtrics survey software. The survey consisted of 36 questions across four primary sections: (1) demographics; (2) standardization; (3) comprehensiveness; and (4) follow-up.

Demographics

The survey began with the collection of demographic information that could not be used to identify the respondent. This information included job title; level of education; years of professional experience; age of students with whom the respondent primarily has contact; training experiences related to SRA; and work experiences related to SRA. Respondents were also asked if they had ever participated in crisis response as a result of a student death by suicide. At the conclusion of the survey, respondents had the option to provide the name of the district in which they are currently employed, with the assurance that this data would be coded numerically prior to analysis.

Standardization

Standardization of tools and procedures used as part of the SRA process is an important aspect of best practice (Boccio, 2015). In the present study, standardization was assessed by asking respondents about the extent to which standardized suicide risk screening and interview tools are utilized in their current job site and at the district level. Respondents were instructed to consider a “standardized” procedure as one which is shared among professionals at their job site and/or district. In order to promote reliability, further contextualization was provided by informing respondents that for the purposes of the survey, a standardized SRA procedure does not have to include a formal measure but may reference screeners or interview protocols with a research basis. Additional items in the standardization section included questions about the use of standardized risk stratification, documentation, and safety contracting procedures at the job site and district levels. The data for the ten standardization items are largely categorical in nature.

Comprehensiveness

The 52 items for the comprehensiveness section were developed using best practice recommendations for areas to be investigated in the course of a suicide risk assessment from the American Psychiatric Association (2003), Boccio (2015), Crepeau-Hobson (2013), and Erbacher and Singer (2018). Using a 3-point Likert scale (“not at all helpful” to “very helpful”), participants responded to the prompt “Please rate the extent to which SRA procedures at your job site help gather information about the following aspects of Current Suicide Status” for each of these components: (1) current suicide status (i.e., current suicide ideation, plan); (2) suicide warning signs; (3) precipitating factors; (4) personal risk factors; (5) family risk factors; (6) behavioral risk factors; (7) cognitive/affective risk factors; and (8) protective factors. Each of these components had between four and ten items that were summed to assess “helpfulness.” Survey directions defined a “helpful” SRA procedure as one which clearly directs the professional to investigate specific aspects of suicide risk. This allowed for investigation of the state of procedures currently in place, rather than what practitioners have learned to do based on their professional experience or level of education.

Follow-up

Based on the missing piece in suicide risk assessment procedures in school-based settings as identified by Erbacher and Singer (2018), the final portion of the survey was composed of 12 items that asked respondents about re-entry procedures following an absence from school due to suicidal ideation or behavior and follow-up procedures after an SRA at their current job site. In addition to providing information regarding the specifics of such procedures, respondents were asked about their perception of various aspects of the suicide risk assessment process at their job site. Using a 5-point Likert-style scale (“strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”), participants rated their level of agreement with the ability of the suicide risk assessment process to (1) accurately identify suicide risk; (2) help team members make informed treatment decisions; (3) facilitate appropriate re-entry procedures; (4) support follow-up procedures to monitor suicide risk; and (5) prevent suicide.

Theoretical Basis for ITS Component Analysis

The present study also examined the extent to which current SRA procedures used by school-based mental health professionals in Colorado align with the ITS components of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability. Although the ITS was not explicitly created to be a standardized suicide risk assessment procedure, there is a growing body of empirical evidence that the three-way interaction between perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and acquired capability can identify suicide risk (Chu et al., 2016; Franklin et al., 2011; Joiner, 2007; Ribeiro et al., 2013) and is significantly predictive of whether a suicidal crisis would involve a suicide attempt versus suicidal ideation (Czyz et al., 2015; Joiner et al., 2009a). Therefore, low levels of alignment between ITS components and related aspects of the risk assessment procedure as evaluated by respondents could indicate potential areas for improvement related to the risk identification and predictive abilities of the school-based SRA process.

For this analysis, 15 items from the comprehensiveness section of the survey were assigned to the categories of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and acquired capability for further analysis. The “helpfulness” ratings participants had assigned to these items via the 3-point Likert scale were used for these analyses, so no additional items were needed. Respondents were not informed that certain items would be used to assess the alignment of the SRA process with ITS components.

As a measure of the perception that one is a burden to others and would be better off dead, the five items contained in the perceived burdensomeness category included feelings of worthlessness, feeling like a burden on others, feelings of shame/guilt, poor academic performance, and history of discipline referrals. The five survey items in the thwarted belongingness category included social withdrawal, poor relationship with parents/caregivers, poor interpersonal problem-solving skills, peer connectedness, and school connectedness. As a measure of the extent to which one becomes inured to one to fear of death or injury via repeated exposure to harmful events, whether self-inflicted or otherwise, the five items in the acquired capability category included preparation/rehearsal of suicidal behavior, history of suicide attempts, hospitalization due to suicidal behavior, current non-suicidal self-injury, and prior non-suicidal self-injury.

Analyses

Standardization

To answer the research question “To what extent do school-based mental health professionals utilize standardized screening tools and interview protocols as part of the SRA process?”, descriptive statistics were calculated for each item.

Comprehensiveness

To answer the research question “How do school-based mental health professionals rate the comprehensiveness of the SRA process in use at their job site?”, descriptive statistics were calculated, and an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. Independent variables included (1) current suicide status; (2) suicide warning signs; (3) precipitating factors; (4) personal risk factors; (5) family risk factors; (6) behavioral risk factors; (7) cognitive/affective risk factors; and (8) protective factors. The dependent variable was the total “helpfulness” score for each independent variable.

Follow-up

To answer the research question “What follow-up procedures are in place to support the SRA process in school settings?”, descriptive statistics were calculated, and an ANOVA was conducted with the independent variables of (1) identify, identify imminent suicide risk; (2) treat, support treatment decision-making; (3) re-entry, includes appropriate re-entry procedures; and (4) follow-up, procedures to monitor suicide risk. The dependent variable was the sum of “agreement,” ratings for statements about the efficacy of each SRA procedure.

Alignment with ITS

To answer the research question “Do SRA procedures in use among school-based mental health professionals in Colorado align with ITS constructs of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability?”, an ANOVA was conducted. Independent variables included selected items from the comprehensiveness component of the survey which were reassigned to create constructs of (1) perceived burdensomeness; (2) thwarted belongingness; and (3) acquired capability. The dependent variable was “helpfulness,” of the SRA in gathering information for each ITS construct.

Results

Experience with SRA

Eleven respondents (15.3%) indicated they had participated in more than 20 SRAs during the previous 12 months. Nine of these respondents were assigned exclusively to secondary settings. The largest proportion of respondents indicated they had participated in 6–10 SRAs in the previous 12 months (38.9%; n = 28), followed by 1–5 SRAs in the previous 12 months (23.6%; n = 17), and 11–20 SRAs in the previous 12 months (19.4%; n = 14). Nearly two-thirds of respondents (63.9%; n = 46) indicated they had provided crisis response to the death of a student by suicide at some point in their careers (see Table 1).

Procedural Standardization

Half of all respondents indicated they use a standardized screener as part of their suicide risk assessment process, while nearly three-quarters (74%) use a standardized interview protocol. The vast majority of respondents (86%) reported that the screener and interview protocol they used were the ones used by all practitioners in their district. The majority of respondents (69%) indicated they ask students to sign a safety contract as part of the SRA process, and 96% of respondents use a risk stratification continuum (e.g., high, medium, and low) to conceptualize overall risk. The graphical representation of these values can be found in Fig. 1.

Comprehensiveness

Respondents rated the comprehensiveness of SRA procedures at their job site based on the components of (1) current suicide status; (2) suicide warning signs; (3) precipitating factors; (4) personal risk factors; (5) family risk factors; (6) behavioral risk factors; (7) cognitive/affective risk factors; and (8) protective factors. Respondents rated each of these components on a 3-point Likert-style scale (“not at all helpful” to “very helpful”) to indicate whether the SRA procedure at their job site supported information gathering in this area. Descriptive statistics for the comprehensiveness items are presented in Table 2. Reliability of the comprehensiveness section of the survey was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The eight comprehensiveness components assessed had Cronbach’s alpha values between .85 and .94, demonstrating good to excellent internal consistency (George & Mallery, 2003).

Helpfulness by Comprehensiveness

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine the difference between the perceived helpfulness of SRA procedures based on the comprehensiveness component. Independent variables included (1) current suicide status; (2) suicide warning signs; (3) precipitating factors; (4) personal risk factors; (5) family risk factors; (6) behavioral risk factors; (7) cognitive/affective risk factors; and (8) protective factors. The dependent variable was the total “helpfulness” score of the component in determining risk. Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were checked and the assumption of homogeneity of variance was violated. ANOVA is robust to this violation due to equal sample sizes between groups. Due to this violation, post hoc tests were conducted using Games–Howell. Bonferroni adjustments were also made due to the multiple comparisons conducted. A significant main effect was found for helpfulness by comprehensiveness, F(7568) = 17.70, p < .001, partial η2 = .18. The effect size of 0.18 is considered large (Cohen, 1988).

Post hoc tests revealed that respondents rated the helpfulness of SRA procedures at gathering information about current suicide status significantly higher than all other components. The helpfulness ratings of SRA procedures in gathering information about cognitive risk factors and family risk factors were significantly lower than the other components.

Follow-up

Approximately one in five respondents (19.4%; n =14) indicated their job site did not have a formalized re-entry process for students who miss school due to suicidal ideation or behavior. Almost 35% (n = 25) were not sure or indicated their job site did not monitor risk in students who had an SRA. Of the respondents who indicated their job site does monitor suicide risk following an SRA (65.3%; n = 47), the majority (89.4%; n = 42) described the characteristics of follow-up procedures at their job site in an optional free-response question. The most common procedure mentioned was periodic check-ins with a mental health provider at school, which was included by all but three of the 42 respondents who provided information.

Perceptions of SRA Procedure Efficacy

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine differences between respondent agreements with statements about the efficacy of SRA procedures. SRA procedures used as independent variables included (1) identify imminent suicide risk; (2) treat/support treatment decision-making; (3) appropriate re-entry procedures; and (4) procedures to monitor suicide risk. The dependent variable was “agreement” that the SRA was effective in gathering the information. Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were checked, and the assumption of homogeneity of variance was violated. ANOVA is robust to this violation due to equal sample sizes between groups. Due to this violation, post hoc tests were conducted using Games–Howell. Bonferroni adjustments were also made due to the multiple comparisons conducted. A significant main effect was found for agreement by procedure, F(3284) = 8.72, p < .001, partial η2 = .08. The effect size of 0.08 is considered moderate (Cohen, 1988). Results indicated that respondents rated their agreement with the ability of SRA procedures to identify imminent suicide risk and support treatment decision-making as significantly higher than their agreement with the ability of SRA procedures to support re-entry and follow-up with students who had previously been identified as being at risk for suicide.

ITS Construct Alignment

Analyses were also conducted to determine the extent to which SRA procedures in use among school-based mental health professionals in Colorado align with the ITS. In order to conduct this analysis, selected items from the comprehensiveness section of the survey were assigned to the three ITS constructs of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and acquired capability (see Table 3). Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The three constructs assessed as part of the ITS analysis had Cronbach’s alpha values between .81 and .87, demonstrating good internal consistency (George & Mallery, 2003). Descriptive statistics for the ITS items are provided in Table 3.

Helpfulness by ITS Constructs

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine the difference between perceived helpfulness of SRA procedures based on ITS constructs. Independent variables included acquired capability, thwarted belongingness, and perceived burdensomeness. The dependent variable was “helpfulness.” Assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were checked, and the assumption of homogeneity of variance was violated. ANOVA is robust to this violation due to equal sample sizes between groups. Regardless, due to this violation, post hoc tests were conducted using Games–Howell. Bonferroni adjustments were also made due to the multiple comparisons conducted. A significant main effect was found for helpfulness by ITS construct, F(2213) = 14.05, p < .001, partial η2 = .12. The effect size of 0.12 is considered moderate (Cohen, 1988). Post hoc tests revealed that the helpfulness of SRA procedures at assessing acquired capability was rated as significantly higher than the helpfulness at assessing thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness.

Discussion

Youth in Colorado appear to be disproportionately impacted by suicide, as the United Health Foundation (2020) reports that Colorado has the highest increase in teen suicide rate in the USA since 2016. As a suicide prevention tool, standardized SRA procedures are intended to identify and guide the treatment of individuals who are at risk for suicide (Gutierrez et al., 2019). However, the limited available literature base indicates that SRA procedures among school-based mental health professionals in Colorado may not be implemented in a standardized or consistent fashion (Crepeau-Hobson, 2013). Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine the scope of standardization, comprehensiveness, and follow-up procedures as part of the school-based SRA process in Colorado. Additionally, this study examined the alignment of school-based SRA procedures with the ITS, which posits that a three-way interaction between the constructs of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability is significantly associated with suicide risk (Joiner, 2005). No previous study has sought to analyze this relationship.

Standardization

Best practice recommendations include the use of standardized tools and procedures as part of the SRA process (Boccio, 2015). Results of the present study indicated a high degree of standardization of SRA procedures across respondents, including the use of standardized interview protocols and a stratification continuum (e.g., high, medium, and low) to conceptualize overall suicidal risk. Additionally, despite a lack of empirical evidence supporting their use (Edwards & Sachmann, 2010; Kelly & Knudson, 2000), standardized safety contracts were also used by the majority of respondents as part of the SRA process. In general, these standardized protocols and procedures were used district-wide, indicating that school districts can play a significant role in the development and standardization of procedures and clinical tools utilized as part of the SRA process.

Comprehensiveness

Screening measures are designed to be over-sensitive to suicide risk in order to ensure identification of high-risk individuals, leading to the need for many follow-up interviews (Joiner et al., 2009a). As such, the comprehensiveness of a given SRA process may be negatively impacted by a school’s personnel and financial limitation (Hallfors et al., 2006). Given such potential limitations, it is vital that the SRA process demonstrates a high level of efficacy in identifying active suicidal ideation, intent, and means. Fortunately, study findings indicate that SRA procedures used generally align with best practice recommendations regarding areas to be investigated during an SRA (Boccio, 2015; Crepeau-Hobson, 2013; Erbacher & Singer, 2018), including current suicide status; personal, family, cognitive/affective, and behavioral risk factors; warning signs; precipitating factors; and protective factors.

Somewhat concerning, however, is that respondents rated the helpfulness of SRA procedures of identifying cognitive risk factors such as thought disturbance (loss of contact with reality), fear of death, and interpersonal problem-solving skills significantly lower than all the other components. Thought disturbance associated with psychiatric comorbidity is significantly associated with suicide risk (Van Orden et al., 2010). Additionally, poor interpersonal problem-solving skills are an aspect of the ITS construct of thwarted belongingness which contributes to the emergence of suicidal ideation (Joiner, 2005). According to the ITS, assessment frameworks should “…explicitly address the degree to which clients feel connected to – and cared about – by others, as well as the degree to which clients believe that they would be better off if they were gone” (Joiner et al., 2009b, p. 57). Thus, cognitive risk factors appear to be directly related to critically important aspects of the SRA process, yet the ability of practitioners to investigate such aspects of suicidal risk may not be adequately supported by current procedures.

Follow-up

Re-entry procedures following absence from school due to suicidal ideation or behavior and follow-up procedures after an SRA have been identified as the missing piece in school-based SRAs (Erbacher and Singer, 2018). Results of the present study indicate that respondents question the ability of SRA procedures to support re-entry and follow-up compared with their ability to identify risk and guide treatment decision-making. Of concern was the lack of a formalized re-entry process for students who miss school due to suicidal ideation or behavior and a lack of monitoring procedures for students who had an SRA in many schools. While some elements of a suicide attempt may be planned well in advance (Smith et al., 2008), information gathered from adult survivors of a suicide attempt indicates that final details regarding the method and location may be decided only hours or days prior to the attempt (Kleiman et al., 2017). Additionally, there is evidence that suicidal behaviors are episodic and tend to fluctuate more rapidly in children than adults (Pisani et al., 2016). Thus, follow-up and monitoring procedures are vital in school settings. Study findings suggest increased development of such procedures among school-based mental health practitioners in Colorado is warranted.

ITS Construct Alignment

While the ITS was not explicitly created to assess suicide risk, there is empirical evidence that the three-way interaction between perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and acquired capability can identify suicide risk (Barzilay et al., 2019; Chu et al., 2016; Franklin et al., 2011; Joiner, 2007; Ribeiro et al., 2013) and is significantly predictive of whether a suicidal crisis would involve a suicide attempt versus suicidal ideation (Czyz et al., 2015; Joiner et al., 2009b). Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are painful interpersonal experiences which can result in the emergence of suicidal desire, while acquiring the capability to harm oneself through habituation to pain and self-injury increases the likelihood one will enact lethal self-harm (Joiner et al., 2009a). Thus, according to the ITS, the combination of capacity for self-harm (acquired capability) and suicidal desire (perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness) is necessary for suicidal behavior to occur (Joiner et al., 2009b). The present study revealed that SRA procedures currently in use among respondents are significantly more helpful at investigating aspects of acquired capability in comparison to thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Given that previous research has highlighted the propensity of youth to engage in various self-harm behaviors as a critical point of intervention (Barzilay et al., 2019) and that the assessment of acquired capability is most salient to identifying imminent risk for suicide (Joiner, 2005; Joiner et al., 2009a), this is encouraging news.

Limitations

The results of this study should be considered in light of its limitations. These limitations include the relatively low response rate, small sample size, and convenience sampling procedure. Survey respondents were largely members of professional organizations and may not be an accurate representation of the general state of practice among school-based mental health professionals. Additionally, this survey gathered responses from school psychologists, school social workers, and school counselors. While data gathered from this group is meaningful in the aggregate, the sample size is not sufficient to gain meaningful comparisons of how SRA procedures may be implemented and perceived differently across disciplines. Therefore, future research into this area of inquiry would benefit from an increased overall sample size, randomized sample group, and a larger group of respondents from social work and counseling backgrounds.

Another limitation is the reliability of self-reported data. While internal consistency measures on the comprehensiveness and ITS constructs were good to excellent, there is no external mechanism through which to ensure that characteristics of self-reported SRA procedures are accurate. However, considering the sample was composed of individuals who are licensed school-based mental health professionals and are largely members of professional organizations, it is likely that information was reported truthfully.

Finally, some survey items were not well defined and that may have impacted how some participants responded. For example, the survey asked if a safety contract was used as part of the SRA process. This could have been interpreted as a no-harm contract or a safety plan, which are two very different strategies, with the former having no evidence of effectiveness (Lewis, 2007; Stanley & Brown, 2012).

Implications and Future Directions

According to the National Association of School Psychologists (2020), “School psychologists, in collaboration with other professionals, engage in crisis intervention, conduct comprehensive suicide and/or threat assessments for students who are identified as at risk, and design interventions to address mental and behavioral health needs.” Clearly, school-based SRA is a crucial and effective tool in this regard. The ability to assess current signs of suicidality and acquired capability is of particular importance as risk behaviors and self-injury are predictive of repeated suicide attempts (Barzilay et al., 2019), and a history of past suicide attempts, particularly violent or medically serious suicide attempts, is among the most powerful risk factors for suicide (Forman et al., 2004; Miranda et al., 2008). Individuals with a history of multiple suicide attempts show increased levels of planning, higher lethality of intent, and increased feelings of regret over recovering from a suicide attempt (Kaslow et al., 2006). As such, it is necessary for school psychologists and other school-based mental health professionals to be able to ascertain the extent to which such experiences are present as a function of the SRA process.

Risk factors such as poor interpersonal problem-solving skills and thought disturbance associated with psychiatric comorbidity are strongly associated with the ITS construct of thwarted belongingness (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). Similarly, warning signs such as feelings of worthlessness, guilt, and burdensomeness are strongly associated with the ITS construct of perceived burdensomeness (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). Thus, the influence of these two constructs in the development of suicidal ideation (Joiner et al., 2009b) should receive increased attention during the SRA process as a means of understanding the mechanism by which ideation emerges.

While vital to immediate risk identification, monitoring cognitive risk factors and social connectedness is also important in the re-entry and follow-up stages of the SRA process (Erbacher and Singer, 2018). School-based mental health professionals generally do not provide long-term psychotherapeutic support to students, and community-based mental health providers are better situated to address certain cognitive and social risk factors for suicide (Armistead and Smallwood, 2014). However, factors such as peer/school connectedness, academic performance, and interpersonal skills can and should be addressed in the school setting (Boccio, 2015; Erbacher & Singer, 2018). Based on this study’s finding that current SRA procedures are significantly more helpful in assessing aspects of acquired capability in comparison to thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, there is a need for increased emphasis on identifying and addressing social, behavioral, and cognitive factors which contribute to the development of suicidal ideation. For example, SRAs should include explicit questions related to the individual’s reasons for living and reasons for dying as this can provide insight regarding their feelings of connection and belongingness, sense of burdensomeness, and hopelessness about the future.

The current study indicates that among school-based mental health professionals in Colorado, current SRA procedures are perceived as effective in assessing imminent suicide risk and support treatment decision-making but are lacking in supporting re-entry and follow-up with students who had previously been identified as being at risk for suicide. As such, follow-up and re-entry procedures are an area in need of general development, and the need may be more acute in secondary settings where the frequency of SRAs is highest.

The present study indicates that progress has been made in the area of SRA documentation and standardization. Analyses revealed that 97.2% of respondents across 17 school districts in Colorado indicated their job site requires documentation of suicide risk assessment. This stands in marked contrast to an exploratory study of school-based suicide risk assessment conducted by Crepeau-Hobson (2013), in which four of eight school districts in a large metropolitan area in the USA did not keep or maintain SRA data and none of the districts approached had formal SRA procedures. As a further measure of progress, half of all respondents in the current study indicated the use of a standardized screener as part of their suicide risk assessment process and nearly three-quarters reported using a standardized interview protocol. Additionally, more than half of all respondents indicated they had received training related to the SRA process within the previous 12 months. This suggests that school-based mental health professionals are willing and able to engage in further training and professional development around SRA procedures. Thus, school districts have an opportunity to capitalize on this convergence of willingness and need by providing focused professional development and standardized procedures to support and improve suicide risk assessment in the school setting.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2003). Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(11 Suppl), 1–60.

Anglin, D., Gabriel, K. O. S., & Kaslow, N. J. (2005). Suicide acceptability and religious wellbeing: A comparative analysis in African American suicide attempters and nonattempters. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 33, 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164710503300207.

Armistead, R. J., & Smallwood, D. L. (2014). The National Association of School Psychologists model for comprehensive and integrated school psychological services. In Best practices in school psychology: Data-based and collaborative decision making (pp. 9–24).

Baiden, P., LaBrenz, C. A., Asiedua-Baiden, G., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2020). Examining the intersection of race/ethnicity and sexual orientation on suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among adolescents: Findings from the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 125, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.02.029.

Barzilay, S., Apter, A., Snir, A., Carli, V., Hoven, C. W., Sarchiapone, M., et al. (2019). A longitudinal examination of the interpersonal theory of suicide and effects of school-based suicide prevention interventions in a multinational study of adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(10), 1104–1111. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13119.

Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., & Roziner, I. (2018). A school-based multilevel study of adolescent suicide ideation in California high schools. The Journal of Pediatrics, 196, 251–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.12.070.

Beautrais, A. L. (2005). National strategies for the reduction and prevention of suicide. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 26(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.26.1.1.

Boccio, D. E. (2015). A school-based suicide risk assessment protocol. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 31(1), 31–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.12.070.

Bryan, C. J., Mintz, J., Clemans, T. A., Leeson, B., Burch, T. S., Williams, S. R., Maney, E., & Rudd, M. D. (2017). Effect of crisis response planning vs. contracts for safety on suicide risk in US Army Soldiers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 212, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.028.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Vital signs - Suicide rising across the U.S. Retrieved February 20, 2020 from https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/index.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). High school YRBSS: Colorado 2019 results. https://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/App/Results.aspx?LID=CO

Chu, C., Buchman-Schmitt, J. M., Hom, M. A., Stanley, I. H., & Joiner Jr., T. E. (2016). A test of the interpersonal theory of suicide in a large sample of current firefighters. Psychiatry Research, 240, 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.03.041.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Crepeau-Hobson, F. (2013). An exploratory study of suicide risk assessment practices in the school setting. Psychology in the Schools, 50(8), 810–822. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21705.

Crepeau-Hobson, F., & Leech, N. L. (2016). Peer victimization and suicidal behaviors among high school youth. Journal of School Violence, 15(3), 302–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.996717.

Czyz, E. K., Berona, J., & King, C. A. (2015). A prospective examination of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among psychiatric adolescent inpatients. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 45(2), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12125.

Edwards, S. J., & Sachmann, M. D. (2010). No-suicide contracts, no-suicide agreements, and no-suicide assurances. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 31(6), 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000048.

Erbacher, T. A., & Singer, J. B. (2018). Suicide risk monitoring: The missing piece in suicide risk assessment. Contemporary School Psychology, 22(2), 186–194.

Forman, E. M., Berk, M. S., Henriques, G. R., Brown, G. K., & Beck, A. T. (2004). History of multiple suicide attempts as a behavioral marker of severe psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(3), 437–443. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.437.

Franklin, J. C., Hessel, E. T., & Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Clarifying the role of pain tolerance in suicidal capability. Psychiatry Research, 189(3), 362–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.08.001.

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Gutierrez, P. M., Joiner, T., Hanson, J., Stanley, I. H., Silva, C., & Rogers, M. L. (2019). Psychometric properties of four commonly used suicide risk assessment measures: Applicability to military treatment settings. Military Behavioral Health, 7, 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/21635781.2018.1562390.

Hallfors, D., Brodish, P. H., Khatapoush, S., Sanchez, V., Cho, H., & Steckler, A. (2006). Feasibility of screening adolescents for suicide risk in “real-world” high school settings. American Journal of Public Health, 96(2), 282–287.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2010). Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 14(3), 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2010.494133.

Hedegaard, H., Curtin, S. C., & Warner, M. (2020). Increase in suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2018. In NCHS Data Brief, no 362. National Center for Health Statistics.

Hom, M. A., Joiner, T. E., & Bernert, R. A. (2016). Limitations of a single-item assessment of suicide attempt history; Implications for standardized suicide risk assessment. Psychological Assessment, 28(8), 1026–1030. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000241.

Ivey-Stephenson, A. Z., Demissie, Z., Crosby, A. E., Stone, D. M., Gaylor, E., Wilkins, N., Lowry, R., & Brown, M. (2020). Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students—youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2019. MMWR supplements, 69(1), 47–55.

Joiner, T. E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press.

Joiner, T. E. (2010). Myths about suicide. Harvard University Press.

Joiner, T. E., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., & Rudd, M. D. (2009b). The interpersonal theory of suicide: Guidance for working with suicidal clients. American Psychological Association.

Joiner, T. E., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Selby, E. A., Ribeiro, J. D., Lewis, R., & Rudd, M. D. (2009a). Main predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 634–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016500.

Kaslow, N. J., Jacobs, C. H., Young, S. L., & Cook, S. (2006). Suicidal behavior among low-income African American women: A comparison of first-time and repeat suicide attempters. Journal of Black Psychology, 32(3), 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798406290459.

Kelly, K. T., & Knudson, M. P. (2000). Are no-suicide contracts effective in preventing suicide in suicidal patients seen by primary care physicians? Archives of Family Medicine, 9(10), 1119–1121.

King, K. A. (2006). Practical strategies for preventing adolescent suicide. The Prevention Researcher, 3(3), 8–10.

King, K. A., & Vidourek, R. A. (2012). Teen depression and suicide: Effective prevention and intervention strategies. The Prevention Researcher, 19(4), 15–18.

King, C. D., Joyce, V. W., Kleiman, E. M., Buonopane, R. J., Millner, A. J., & Nash, C. C. (2019). Relevance of the interpersonal theory of suicide in an adolescent psychiatric inpatient population. Psychiatry Research, 281, 112590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112590.

Kleiman, E. M., Turner, B. J., Fedor, S., Beale, E. E., Huffman, J. C., & Nock, M. K. (2017). Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: Results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(6), 726–738. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000273.

Lewis, L. M. (2007). No-harm contracts: A review of what we know. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 37(1), 50–57.

Marraccini, M. E., & Brier, Z. M. (2017). School connectedness and suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A systematic meta-analysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000192.

McKay, T., Berzofsky, M., Landwehr, J., Hsieh, P., & Smith, A. (2019). Suicide etiology in youth: Differences and similarities by sexual and gender minority status. Children and Youth Services Review, 102, 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.03.039.

Miranda, R., Scott, M., Hicks, R., Wilcox, H. C., Munfakh, J. L. H., & Shaffer, D. (2008). Suicide attempt characteristics, diagnoses, and future attempts: Comparing multiple attempters to single attempters and ideators. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(1), 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56cb.

National Association of School Psychologists. (2020). Model for comprehensive and integrated school psychological services. Author Retrieved from https://www.nasponline.org/standards-and-certification/nasp-practice-model/about-the-nasp-practice-model.

Nock, M. K., & Kessler, R. C. (2006). Prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts versus suicide gestures: Analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(3), 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.616.

Pisani, A. R., Murrie, D. C., & Silverman, M. M. (2016). Reformulating suicide risk formulation: From prediction to prevention. Academic Psychiatry, 40(4), 623–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-015-0434-6.

Ribeiro, J. D., Bodell, L. P., Hames, J. L., Hagan, C. R., & Joiner, T. E. (2013). An empirically based approach to the assessment and management of suicidal behavior. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(3), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031416.

Smith, A. R., Witte, T. K., Teale, N. E., King, S. L., Bender, T. W., & Joiner, T. E. (2008). Revisiting impulsivity in suicide: Implications for civil liability of third parties. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 26(6), 779–797. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.848.

Stanley, B., & Brown, G. K. (2012). Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.01.001.

Sulkowski, M. L., & Simmons, J. (2018). The protective role of teacher–student relationships against peer victimization and psychosocial distress. Psychology in the Schools, 55(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22086.

Thompson, M. P., Kaslow, N. J., & Kingree, J. B. (2002). Risk factors for suicide attempts among African American women experiencing recent intimate partner violence. Violence and Victims, 17, 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.17.3.283.33658.

United Health Foundation. (2020). Teen suicide in Colorado. Retrieved from https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/health-of-women-and-children/measure/teen_suicide/state/CO

Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018697.

Williams, S., Schneider, M., Wornell, C., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2018). Student’s perceptions of school safety: It is not just about being bullied. The Journal of School Nursing, 34(4), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840518761792.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board in 2019. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davenport, J.R., Crepeau-Hobson, M.F. School-Based Suicide Risk Assessment: Standardization, Comprehensiveness, and Follow-up Procedures in Colorado. Contemp School Psychol 27, 262–274 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-021-00383-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-021-00383-4