Abstract

We conducted a systematic review of research on school psychologists’ job attitudes. To do so, all available published research and dissertations (N = 58) on school psychologists’ job attitudes were gathered and evaluated to address three research questions. First, we identified themes in the study of school psychologists’ job attitudes. Themes identified were how job attitudes relate to roles, differences between actual and ideal roles, place of school psychology practice, personality and individual characteristics, and burnout. Second, we documented types of job attitudes studied. Here, results indicated that job satisfaction was the most commonly studied job attitude with most school psychologists reporting average to above average levels of job satisfaction. Finally, we attempted to examine the link between school psychologists’ job attitudes with productive and counterproductive work behaviors. However, our review indicated that there has been no examination of the relationship between these variables. Future research will want to explore the link between job attitudes, such as job satisfaction, but others attitudes as well, and job behaviors. This is important as the field of school psychology is facing critical labor shortages, and research in this area will assist with recruitment and retention efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In its 2018–2019 policy platform, the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) presented six goals to support the vision that all children thrive at school and home (NASP 2017). The second goal specified that shortages of school psychologists be addressed, and it proposed doing so through a series of objectives calling for increasing the recruitment and retention of school psychologists, especially from underrepresented communities, and the alignment of staffing ratios for school psychologists with NASP suggested guidelines. Shortages of school psychologists have a long history of documentation dating back at least to the late 1980s (Fagan 1988), but current shortages are at critical levels. Castillo et al. (2014) examined data from NASP and found that the projected shortage of school psychologists is expected to continue until 2025. Given current and predicted critical shortages of school psychologists, factors that impact recruitment and retention are important to study. One such a factor is job attitudes.

Job attitudes, like attitudes in general, have affective, behavioral, and cognitive components, and they refer to evaluations of one’s job (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller 2012). Although there are a number of job attitudes, the most often studied is job satisfaction which refers to positive evaluations of one’s job. One reason for the study of job attitudes is that they are predictive of a number of productive and counterproductive workplace behaviors. With regard to productive workplace behaviors, there is a positive relationship between job satisfaction and job performance (Judge et al. 2017). A link between job attitudes and counterproductive workplace behaviors was been established. In a review of more than 100 years of research on job attitudes, Judge et al. (2017) found that job attitudes, and, in particular, lower levels of job satisfaction, were related to withdrawal behaviors. Withdrawal behaviors are those that attempt to change an untenable work situation. They fall on a continuum and range from arriving at work late and/or leaving work early to turnover. Withdrawal behaviors have tremendous costs associated with them with the Society of Human Resource Management (2016) noting that hiring a replacement employee, on average, costs over $4000, and the average time to hire a replacement employee is estimated at 42 days. For school psychology, a field where the demand outweighs supply, particularly in rural and some urban areas, counterproductive workplace behaviors may be especially problematic as they may exacerbate personnel shortages (Castillo et al. 2014).

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review of research on school psychologists’ job attitudes. Systematic review is a method used to gather, synthesize, and evaluate all existing evidence on a specific topic. It has a long history of use in the health sciences and is many times the first step in conducting a meta-analysis (Shamseer et al. 2015). Systematic reviews are potentially useful because they allow for a broad understanding and synthesis of the research and to set a research agenda (Torraco 2005, 2016). Here, all available published research and dissertations on school psychologists’ job attitudes were gathered and evaluated to respond to three research questions. First, what are themes in the study of school psychologists’ job attitudes? Second, what types of job attitudes have been studied? Finally, what is the relationship of school psychologists’ job attitudes with productive and counterproductive work behaviors?

Method

The preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis-revised method (PRISMA-R) was used to gather study data (Moher et al. 2015). PRISMA-R is a framework that guides researchers in the conduct of a systematic review (Moher et al. 2015). It is a 17-step process that involves, if applicable, registering the systematic review with appropriate reporting agencies; delineating the rationale for and objectives of the review; and, finally, a series of steps related to the process of conducting the review.

Search Procedures

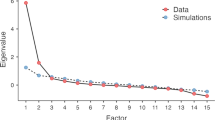

To conduct the systematic review, a number of steps were followed. This process is shown in the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1. First, applicable key terms were identified by examining those used in recently published articles on school psychologists’ job attitudes (e.g., Weaver and Allen 2017). The first set of key terms was job attitude, job satisfaction, turnover intent, and organizational commitment. The second set was school psychologist, child study team, and school personnel. Key terms from the two sets were combined until all possible combinations were exhausted. The databases searched were EBSCO Host Web, PQ Web, Sage Premier, and Science Direct. For EBSCO Host Web and PQ Web, which are search engines that contain multiple databases, searches included all possible databases within the database network. We searched for qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method studies. Searches were limited to dissertations published in English and studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals. The process of combining the keywords was repeated in each of the databases used for the study. This phase of the systematic review was conducted between late summer and fall 2017.

The initial keyword searches yielded 1553 studies. The authors scanned the study titles to determine which were potentially relevant and which were duplicates. After this process, 102 studies were identified for possible inclusion. Those studies were discussed until the authors reached 100% agreement about the relevance of the identified study to the review. Identified study reference lists were examined to obtain other relevant studies that may not have been indexed in any of the database searches. At the end of this process, 58 studies met criteria for inclusion in this review. They are shown in Table 1. Finally, researchers who had published more than one study in this area were emailed to solicit any unpublished studies. Of the six authors who were emailed, three replied and indicated that they did not have any additional materials for this systematic review.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were specified prior to the database searches. To be included in the review, studies had to have the following characteristics. Studies needed to be empirical (i.e., propose hypotheses or research questions and collect quantitative and/or qualitative data). Study participants had to include practicing school psychologists. At least one of the constructs examined in the study had to be job attitudes. Published studies or dissertations had to be written in English. Non-empirical studies were not included in the review. Studies published in a language other than English were not included in the review. Except for dissertations, only studies published in peer-reviewed journals were included in the review.

Results

Themes in the Study of School Psychologists’ Job Attitudes

Themes identified were job attitudes and their relationship to school psychologists’ roles, differences between actual and ideal roles, place of school psychology practice, personality and individual characteristics, and burnout. The themes, the percent of studies examining each theme, and a sample study research objective for each theme appear in Table 2. Below, we discuss each theme individually although many times they interacted with one another.

School psychologists’ roles (i.e., job duties) are a prominent theme in research in this area. Here, job attitudes and their relationship to school psychologists’ types of roles have a long history of study dating back to the 1970s (Bolling 2014; Brown et al. 2006b; Carroll et al. 1981; Clair et al. 1972; Hughes and Clark 1981; Jerrell 1984; Lisbon-Peoples 2015; Pincus and Olson 1997). As a whole, this research indicates that varied job duties are associated with more positive job attitudes. One of the earliest studies to document this was published by Jerrell (1984) who studied boundary spanning activities (i.e., managing aspects of the environment and their impact on school functioning) of school psychologists and their relationship to job satisfaction. Results indicated that school psychologists with more boundary spanning activities, such as consulting with teachers and having input on funding allocation, were more satisfied than those with fewer boundary spanning activities. Some of this research involved defining the role of the school psychologist and the professionalization of the occupation. For example, Clair et al. (1972) studied areas of job dissatisfaction as a way to begin a discussion of defining the school psychologist’s role, identifying solutions for problematic aspects of the role, and improving psychological services in the schools.

Actual roles and job duties of school psychologists, as compared to their ideal roles and job duties, and their impact on job attitudes were also examined (Cottrell and Barrett 2015; Huebner 1993; Hughes and Clark 1981; Hussar 2015; Jerrell 1984; Levinson 1990; Reschly and Wilson 1995; Smith and Lyon 1985; Solly and Hohenshil 1986; Wright and Gutkin 1981). A typical finding from this area of inquiry is that school psychologists prefer to engage in fewer assessment-related activities and more consultative services and system-wide interventions, and these preferences impact job satisfaction (Levinson 1990; Reschly and Wilson 1995). Larger discrepancies between actual and ideal roles have been associated with lower levels of job satisfaction for school psychologists. Other research indicated that factors such as dissatisfaction with SLD assessment can negatively impact school psychologists’ job satisfaction (Cottrell and Barrett 2015). Unruh and McKellar (2013) found that school psychologists who worked in schools using a Response to Intervention (RtI) framework were more likely to indicate that they were satisfied with their job than those who did not. Hill (2011) found that school psychologists who used a flexible RtI model had higher levels of job satisfaction than those who used a prescriptive RtI model.

Often interweaved within the study of roles is the study of the relationship of place of practice to school psychologists’ job attitudes. Here, researchers examined how location of school psychology practice, whether in rural, urban, or suburban settings, impacts job satisfaction (Ehly and Reimers 1986; Goforth et al. 2017; Hosp and Reschly 2002; Huebner et al. 1984; Hughes and Clark 1981; Hussar 2015; Meacham and Peckham 1978; Reschly and Connolly 1990; Solly and Hohenshil 1986). Results were mixed. In one of the earliest studies of the relationship of place to school psychologists’ job attitudes, Hughes and Clark (1981) found that although rural school psychologists had greater role diversity, there were no significant differences in job satisfaction between them and their urban counterparts. Data from a recently conducted study also found that although rural school psychologists had greater role diversity than either their suburban or urban counterparts, they were more only more satisfied than their suburban counterparts (Goforth et al. 2017).

Research is not limited to school psychologists practicing in the United States (US). Burden (1988) examined ratings of stressful work situations among school psychologists in three countries. Results indicated that although there were some differences among US, English, and Australian school psychologists, all perceived receiving information from their supervisors about their own unsatisfactory job performance was the most stressful work situation. Others also examined job attitudes among school psychologists in countries other than the US (Idsoe 2006; Idsoe et al. 2008; Jordan et al. 2009; Kavenská et al. 2013). Like their US counterparts, participants in these studies tend to report average to high levels of job satisfaction.

The relationship of personality and other individual characteristics to job attitudes has been studied (Crosson 2016; DeLuzio 2014; Ehly and Reimers 1986; Huebner and Mills 1994; Levinson et al. 1994; Raviv et al. 2002; Wilson and Reschly 1995; Wright and Thomas 1982). Findings from these studies indicate that older and tenured school psychologists report higher levels of job satisfaction than younger and untenured school psychologists (DeLuzio 2014; Wilson and Reschly 1995; Wright and Thomas 1982). For example, Wright and Thomas found that younger school psychologists, who were more likely to be untenured, experienced greater role strain and lower job satisfaction than did their older, and possibly tenured, counterparts. DeLuzio (2014), Ehly and Reimers (1989), Levinson et al. (1994), Raviv et al. (2002), and Wilson and Reschly (1995) examined the relationship of gender to school psychologists’ job satisfaction. As a whole, results from these studies indicated that there were few, if any, differences in levels of job satisfaction between women and men school psychologists.

Others examined the relationship of school psychologists’ personality characteristics to job satisfaction and other aspects of workplace functioning (DeLuzio 2014; Huebner and Mills 1994; Sandoval 1993). Deluzio (2014) found that school psychologists who had an internal locus of control had significantly higher levels of job satisfaction than those with an external locus of control. The primary focus of study for both Huebner and Mills (1994) and Sandoval (1993) was on school psychologists’ personality characteristics and their relationship to burnout. Using a measure of personality, Sandoval found that more well-adjusted school psychologists were less likely to experience burnout. Huebner and Mills (1994) found that school psychologists who were extraverted and agreeable were less likely to experience burnout. Although neither Sandoval nor Huebner and Mills studied intent to turnover, a job attitude which is frequently studied in the burnout literature, it may be reasonably inferred that those school psychologists with personality traits that made the less susceptible to burnout would be less likely to turnover.

Regarding burnout, numerous studies on job attitudes have looked at their relationship to this variable (Boccio et al. 2016; Huebner 1993; Huebner and Mills 1994; Huberty and Huebner 1988; Mackoniené and Norvilé 2012; Pierson-Hubeny and Archambault 1987; Proctor and Steadman 2003; Reiner and Hartshorne 1982; Sandoval 1993; Weaver and Allen 2017). Burnout refers to a syndrome that leads to decreases in personal resources brought about by prolonged and continuous exposure to stress (Maslach et al. 2012). It has three distinct components. The first, emotional exhaustion, is the depletion of emotional resources as a result of job demands. The second, depersonalization, is hardened attitudes toward those with whom one works. The final component is a reduced sense of personal accomplishment.

As an example of this line of inquiry, Heubner and colleagues conducted a series of studies on the relationship of burnout to school psychologists’ work roles (Huberty and Huebner 1988; Huebner 1992; Huebner and Mills 1994). Huberty and Huebner (1988) surveyed NASP members, and found that role ambiguity and excessive demands (e.g., heavy caseload) were associated with burnout. Huebner (1992), in a survey of NASP members, found that emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were related to lower levels of job and supervisor satisfaction as well as higher levels of intention to turnover.

Types of Job Attitudes Studied

With regard to the types of job attitudes studied, most research focused on job satisfaction. In fact, nearly every study reviewed here focused primarily on job satisfaction. In many cases, job satisfaction was the only job attitude studied (e.g., Unruh and McKellar 2013). Exceptions to this include some of the studies that examined burnout among school psychologists. For example, in their research on burnout among school psychologists, in addition to studying job satisfaction, Boccio et al. (2016) also studied turnover intentions as did Huebner and Mills (1994). Turnover intentions were also studied by Carroll et al. (1981), Wright and Thomas (1982), Solly and Hohenshil (1986) and Levinson et al. (1988) who, similar to Boccio et al. (2016) and Huebner and Mills (1994), found relatively low intentions to turnover among participants.

Results from most studies included in this review indicated that school psychologists report average to above average levels of job satisfaction (Anderson et al. 1984; Idsoe 2006; Weaver and Allen 2017). In a meta-analysis of a subset of studies examining school psychologists’ job attitudes, VanVoorhis and Levinson (2006) reported that 84% of school psychologists are satisfied with their jobs. This number stands in contrast to the 51% of US workers who reported being satisfied with their jobs (The Conference Board 2017). Recent research (e.g., Boccio et al. 2016) reported comparable levels of job satisfaction among school psychologists.

For many of the studies included in this systematic review, job satisfaction was measured with one or a few questions which were developed in an ad hoc fashion. The studies using the Minnesota Satisfaction Survey (MSQ) are an exception to this. Some of these studies were conducted before 2006, and included in a meta-analysis by VanVoorhis and Levinson (2006). The MSQ has continued to be used on occasion. For example, Hill (2011) used the MSQ in a study of how RtI models impacted school psychologists’ job satisfaction. Others, such as Weaver and Allen (2017), used measures of job satisfaction that have been demonstrated to have adequate psychometric properties.

The use of measures with demonstrated adequate psychometric properties, such as the MSQ, is important. This issue was addressed by Brown et al. (2006a) who compared two measures of job satisfaction (MSQ, Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS)) with one another. The JSS, developed by Reschly and Wilson (1995), to measure school psychologists’ job satisfaction, was found to be comparable to the MSQ. There were some differences, and Brown et al. (2006a) cautioned that researchers need to be aware of those differences when selecting measures of job satisfaction.

Researchers of job attitudes from industrial/organizational (I/O) psychology often use questionnaires such as the MSQ that allow them to study facets of the job with which employees are the most and least satisfied, and some researchers of school psychologists’ job attitudes have given this examination (Anderson et al. 1984; Levinson 1991; Reschly and Wilson 1995; Solly and Hohenshil 1986). Facets of their jobs with which school psychologists are most satisfied are related to the work itself (i.e., the job activities, the service provided to others, the fulfillment of one’s values through performing the job). Facets of their jobs with which school psychologists are least satisfied are advancement, pay, and policies and procedures.

Relationship of Job Attitudes to Work Behaviors

An additional research question was to examine the relationship of school psychologists’ job attitudes with productive and counterproductive work behaviors. However, none of the studies included in this systematic review explored the relationship. Williams and Williams (1990) measured school psychologists’ self-perceptions of their competence, but there was no objective assessment of their job performance. In addition, there is almost no mention of exploring the link between job attitudes and job behaviors in the reviewed literature. Cottrell and Barrett (2015) are an exception to this. In their study of RtI assessment practices, they suggested looking at the link between job attitudes and job behaviors as they may have implications for recruitment and turnover in school psychology.

Other Findings

A feature of this body of research, especially apparent in recently published studies, is the shortage of school psychologists as an impetus for research on job attitudes and related constructs (Boccio et al. 2016; Cottrell and Barrett 2015; Weaver and Allen 2017). For example, Boccio et al. discussed various factors, the aging school psychology workforce, and other reasons for attrition. Many of these studies make reference to Castillo et al. (2014) research discussing the current and projected shortages of school psychologists and graduate educators. Here, researchers reason that by studying job attitudes and their effect on counterproductive workplace behaviors, such as turnover, personnel shortages may be alleviated. Another feature of this body of research is the examination of job attitudes as a dissertation topic. All of these were conducted in the current decade (Bolling 2014; Crosson 2016; DeLuzio 2014; Desai 2016; Hill 2011; Hussar 2015; Lisbon-Peoples 2015; Rochester-Olang 2011).

Discussion

To summarize, research reviewed here indicates that there are a number of themes in the study of school psychologists’ job attitudes. These include the examination of job attitudes and their relationship to school psychologists’ roles, differences between actual and ideal roles, place of school psychology practice, personality and individual characteristics, and burnout. Varied job duties are associated with more positive job attitudes (e.g., Jerrell 1984). Results related to place of practice are mixed with some research indicating that there are no significant relationships between place of practice and school psychologists’ job attitudes (e.g., Hughes and Clark 1981) and other research indicating rural school psychologists were more satisfied than their suburban counterparts (e.g., Goforth et al. 2017). Regarding actual and ideal roles, school psychologists prefer to engage in fewer assessment-related activities and greater consultative services and system-wide interventions and such preferences impact job satisfaction (e.g., Reschly and Wilson 1995). Research examining personality characteristics of school psychologists and their relationship to job satisfaction led to a number of findings; perhaps, the most frequently replicated is that older and tenured school psychologists report higher levels of job satisfaction than younger and untenured school psychologists (e.g., DeLuzio 2014). In the series of studies examining the relationship of burnout to job attitudes, research indicated that role ambiguity and excessive demands (e.g., heavy caseload) were associated with burnout and that components of burnout were related to lower levels of job and supervisor satisfaction as well as higher levels of intention to turnover (e.g., Huebner 1993).

With regard to the types of job attitudes studied, job satisfaction is, by far, the most commonly studied although research on burnout among school psychologists has also examined turnover intentions (e.g., Boccio et al. 2016). School psychologists report average to above average levels of job satisfaction and are typically found to have higher levels of job satisfaction than most US workers (Weaver and Allen 2017). In the literature reviewed here, attitudes were, at times, measured with one or a few questions which were developed in an ad hoc fashion potentially calling into question study findings.

Finally, results from this review indicate that there has been no examination of the relationship between job attitudes and job behaviors. This is unusual because it is typical for researchers who study attitudes to attempt to link them to behaviors (Judge et al. 2017). This is true for researchers in I/O psychology as well as researchers in social psychology who originated the scientific study of attitudes and their behavioral correlates.

Other findings identified were the shortages of school psychologists as an impetus for research in this area and the examination of job attitudes as a dissertation topic. With regard to the latter, it is reasonable to assume that the study of school psychologists’ job satisfaction is used as a vehicle for degree completion. It may also be reasonable to assume that many of the researchers pursue careers as practicing school psychologists and not school psychology trainers. Although the implications of these assumptions are not necessarily negative or positive, these researchers may be less likely to continue to engage in research on school psychologists’ job attitudes rendering exploration of this area as less than systematic.

This systematic review has limitations. Attempts were made to identify published and gray (i.e., unpublished studies or studies not published in indexed journals) literature; however, it is possible that additional studies examining school psychologists were not included in this review. Other limitations stem from the reviewed studies. All studies were cross-sectional where findings are subject to cohort effects and related methodological shortcomings (Whitley and Kite 2013). The use of single-item measures does not allow for an examination of the reliability and validity of these measurement tools (Whitley and Kite 2013).

Implications for Research and Addressing Personnel Shortages

More research in this area is warranted. Researchers may want to examine other types of job attitudes including job involvement, organizational commitment, and work-life balance. These constructs have a rich history of study in I/O psychology where research indicates that these variables have an important role in workplace functioning (Allen 2013). It is important that any additional research be conducted using measures that have been demonstrated to have adequate psychometric properties. There are many reliable and valid measures of job attitudes. Researchers interested in continuing the exploration of school psychologists’ job attitudes would be advised to use these measures.

There is evidence that like most US workers, older school psychologists report higher levels of job satisfaction than do younger school psychologists. Researchers may want to conduct a more systematic examination of the trajectory of school psychologists’ job attitudes over the course of their careers. Doing so would involve the use of longitudinal research designs.

An additional area of inquiry should examine the relationship between job attitudes and job behaviors. For example, researchers may want to examine the link between job attitudes and job performance. This is an often studied, but still controversial area within I/O psychology, with mixed findings on the relationship between these variables (Judge et al. 2017). Another area for exploration is an examination of job attitudes and withdrawal behaviors. Withdrawal behaviors are those that attempt to change an untenable work situation. They can have enormous costs for organizations and efforts to lessen them can be meaningful.

As discussed earlier, research indicates that by studying job attitudes and their linkage to behaviors such as turnover, personnel shortages may be alleviated. For this to happen, there must be actual study of the relationship between job attitudes and job behaviors. Also, because school psychologists do enjoy relatively high levels of job satisfaction, any gain attached to increasing job satisfaction may be minimal. It is important to consider other ways to address personnel shortages. These include advocating for the allocating of more school psychology positions and working more vigorously to recruit individuals, especially from diverse backgrounds, to the profession (NASP 2017). One way to better recruit individuals to the profession may be promotion of the finding of this review that school psychologists enjoy high levels of job satisfaction relative to other professionals.

Conclusions

While the study of job attitudes and their relationship to job behaviors has important theoretical implications, the practical implications are also important. For school psychologists, who experience higher levels of job satisfaction than most workers, practical implications include the relationship of job attitudes and behaviors to critical shortages within the field. Studying the relationships between these variables may take on greater importance as shortages are expected to increase.

References

Allen, T. D. (2013). The work-family role interface: A synthesis of the research from industrial and organizational psychology. Handbook of Psychology, vol. 12: Industrial and Organizational Psychology (2nd ed.). (pp. 698-718) John Wiley & Sons Inc., Hoboken, NJ. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1230620202?accountid=27354.

Anderson, W. T., Hohenshil, T. H., & Brown, D. T. (1984). Job satisfaction among practicing school psychologists: A national study. School Psychology Review, 13(2), 225–230 Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/publications/periodicals/spr/volume-13/volume-13-issue-2/job-satisfaction-among-practicing-school-psychologists.

Boccio, D. E., Weisz, G., & Lefkowitz, R. (2016). Administrative pressure to practice unethically and burnout within the profession of school psychology. Psychology in the Schools, 53(6), 659–672. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21931.

Bolling, M. A. (2014). From traditional to reform: Exploring the involvement of school psychologists in the provision of educator professional learning (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Central. (Order No. 3583642).

Brown, M. B., Hardison, A., Bolen, L. M., & Walcott, C. M. (2006a). A comparison of two measures of school psychologists’ job satisfaction. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 21, 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573506298830.

Brown, M. B., Holcombe, D. C., Bolen, L. M., & Thomson, W. S. (2006b). Role function and job satisfaction of school psychologists practicing in an expanded role model. Psychological Reports, 98, 486–496. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.98.2.486-496.

Burden, R. L. (1988). Stress and the school psychologist: A comparison of potential stressors in the lives of school psychologists in three continents. School Psychology International, 9(1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034388091009.

Carroll, J. L., Bretzing, B. H., & Harris, J. D. (1981). Psychologists in secondary schools: Training and present patterns of service. Journal of School Psychology, 19(3), 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4405(81)90046-7.

Castillo, J. M., Curtis, M. J., & Tan, S. Y. (2014). Personnel needs in school psychology: A 10-year follow-up study on predicted personnel shortages. Psychology in the Schools, 51(8), 832–849 https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21786.

Chafouleas, S. M., Clonan, S. M., & Vanauken, T. L. (2002). A national survey of current supervision and evaluation practices of school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 39(3), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10024.

Clair, T. N., Kerfoot, W. D., & Klausmeier, R. (1972). Dissatisfaction of practicing school psychologists with their profession. Psychology in the Schools, 20–23.

Cottrell, J. M., & Barrett, C. A. (2015). Job satisfaction among practicing school psychologists: The impact of SLD identification. Contemporary School Psychology, 20(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0076-4.

Crosson, J. B. (2016). Moderating effect of psychological hardiness on the relationship between occupational stress and self-efficacy among Georgia school psychologists (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from PsycINFO. (Order No. AAI3687467).

DeLuzio, S. I. (2014). The satisfied school psychologist: The moderating impact of locus of control on the relationship between school climate and job satisfaction (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from PsycINFO. (Order No. AAI3604531).

Desai, S. P. (2016). Supervisory dyads in school psychology internships: Does personality difference affect ratings of supervisory working alliance, supervision satisfaction, and work readiness? (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from PsycINFO. (Order No. AAI10118497).

Ehly, S., & Reimers, T. M. (1986). Perceptions of job satisfaction, job stability, and quality of professional life among rural and urban school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 23, 164–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(198604)23:2%3C164::AID-PITS2310230209%3E3.0.CO;2-Z.

Ehly, S., & Reimers, T. M. (1989). Gender differences in job site perceptions. Special Services in the Schools, 4, 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1300/J008v04n03_08.

Fagan, T. K. (1988). The historical improvement of the school psychology service ratio: Implications for future employment. School Psychology Review, 17(3), 447–458 Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/617512330?accountid=27354.

Goforth, A. N., Yosai, E. R., Brown, J. A., & Shindorf, Z. R. (2017). A multi-method inquiry of the practice and context of rural school psychology. Contemporary School Psychology, 21, 58–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-016-0110-1.

Hill, S. L. (2011). Implementation of response to intervention models and job satisfaction of school psychologists (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from PsycINFO. (Order No. AAI3413120).

Hosp, J. L., & Reschly, D. J. (2002). Regional differences in school psychology practice. School Psychology Review, 31(1), 11–29 Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/publications/periodicals/spr/volume-31/volume-31-issue-1/regional-differences-in-school-psychology-practice.

Huberty, T. J., & Huebner, E. S. (1988). A national survey of burnout among school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 25, 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(198801)25:1%3C54::AID-PITS2310250109%3E3.0.CO;2-3.

Huebner, E. S. (1992). Burnout among school psychologists: An exploratory investigation into its nature, extent, and correlates. School Psychology Quarterly, 7(2), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088251.

Huebner, E. S. (1993). Psychologists in secondary schools in the 1900s: Current functions, training, and job satisfaction. School Psychology Quarterly, 8(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088831.

Huebner, E. S., & Mills, L. B. (1994). Burnout in School Psychology: The contribution of personality characteristics and role expectations. Special Services in the Schools, 8(2), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1300/J008v08n02_04.

Huebner, E. S., & Wise, P. S. (1991). Role expansion: Networking functions of Illinois school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 28(2), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199104)28:2<171::AID-PITS2310280212>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Huebner, E. S., McLeskey, J., & Cummings, J. A. (1984). Opportunities for school psychologists in rural school settings. Psychology in the Schools, 21(3), 325–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(198407)21:3<325::AID-PITS2310210309>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Hughes, J. N., & Clark, R. D. (1981). Differences between urban and rural school psychology: Training implications. Psychology in the Schools, 18(2), 191–196. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(198104)18:2<191::AID-PITS2310180214>3.0.CO;2-W.

Hussar, J. M. (2015). Examining the differences in roles and functions of school psychologists among community settings: Results from a national survey (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Central. (Order No. 3739356).

Idsoe, T. (2006). Job aspects in the school psychology service: Empirically distinct associations with positive challenge at work, perceived control at work, and job attitudes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15, 46–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320500411514.

Idsoe, T., Hagtvet, K. A., Bru, E., Midthassel, U. V., & Knardahl, S. (2008). Antecedents and outcomes of intervention program participation and task priority change among school psychology counselors: A latent variable growth framework. Journal of School Psychology, 46, 23–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.01.001.

Jerrell, J. M. (1984). Boundary-spanning functions served by rural school psychologists. Journal of School Psychology, 22, 259–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4405(84)90007-4.

Jordan, J. J., Hindes, Y. L., & Saklofske, D. H. (2009). School psychology in canada: A survey of roles and functions, challenges and aspirations. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 24(3), 245–264. http://dx.doi.org.library.georgian.edu:2048/10.1177/0829573509338614.

Judge, T. A., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. (2012). Job attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 341–367 http://dx.doi.org.library.georgian.edu:2048/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-.

Judge, T. A., Weiss, H. M., Kammeyer-Mueller, J., & Hulin, C. L. (2017). Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: A century of continuity and of change. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 356–374 http://dx.doi.org.library.georgian.edu:2048/10.1037/apl0000181.

Kavenská, V., Smékalová, E., & Šmahaj, J. (2013). School psychology in the Czech Republic: Development, status, and practice. School Psychology International, 34(5), 556–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034312469759.

Levinson, E. M. (1989). Job satisfaction among school psychologists: A replication study. Psychological Reports, 65, 579–584. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1989.65.2.579.

Levinson, E. M. (1990). Actual and desired role functioning, perceived control over role functioning, and job satisfaction among school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 27, 64–74.

Levinson, E. M. (1991). Predictors of school psychologists satisfaction with school system policies/practices and opportunities for advancement. Psychology in the Schools, 28, 256–266.

Levinson, E. M., Fetchkan, R., & Hohenshil, T. H. (1988). Job satisfaction among practicing school psychologists revisited. School Psychology Review, 17(1), 101–112. Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/publications/periodicals/spr/volume-17/volume-17-issue-1/job-satisfaction-among-practicing-school-psychologists-revisited.

Levinson, E. M., Rafoth, M. A., & Sanders, P. (1994). Employment-related differences between male and female school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 31, 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199407)31:3%3C201::AID-PITS2310310305%3E3.0.CO;2-M.

Lisbon-Peoples, A. (2015). Reclaiming our identity: School psychologists' perceptions of their roles in education based on social, political, and economic changes (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from PsycINFO. (Order No. AAI3617796).

Mackoniené, & Norvilé, N. (2012). Burnout, job satisfaction, self-efficacy, and proactive coping among Lithuanian school psychologists. Tiltai, 60(3), 199–211 Retrieved from http://journals.ku.lt/index.php/tiltai/article/view/425.

Male, D. B., & Male, T. (2003). Workload, job satisfaction and perceptions of role preparation of principal educational psychologists in England. School Psychology International, 24(3), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343030243001.

Maslach, C., Leiter, M. P., & Jackson, S. E. (2012). Making a significant difference with burnout interventions: Researcher and practitioner collaboration. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 296–300. http://dx.doi.org.library.georgian.edu:2048/10.1002/job.784.

Meacham, M. L., & Peckham, P. D. (1978). School psychologists at three-quarters century: Congruence between training, practice, preferred role and competence. Journal of School Psychology, 16(3), 195–206. http://dx.doi.org.library.georgian.edu:2048/10.1016/0022-4405(78)90001-8.

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L., & the PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis-revised method (PRISMA-R). BioMed Central, 4. Retrieved from https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

National Association of School Psychologists. (2017). Federal Public Policy and Legislative Platform for the First Session of the 115th Congress (2018-2019) [Policy platform]. Bethesda: Author.

Pierson-Hubeny, D., & Archambault, F. X. (1987). Role stress and perceived intensity of burnout among school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 24(3), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(198707)24:3<244::AID-PITS2310240309>3.0.CO;2-I.

Pincus, A. J., & Olson, J. E. (1997). Professional and organizational socialization and school psychologists’ commitment to students. Journal for a Just and Caring Education, 3(3), 298–316.

Proctor, B. E., & Steadman, T. (2003). Job satisfaction, burnout, and perceived effectiveness of “in-house” versus traditional school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 40(2), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10082.

Raviv, A., Mashraki-Pedhatzur, S., Raviv, A., & Erhard, R. (2002). The Israeli school psychologist: A professional profile. School Psychology International, 23(3), 283–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034302023003233.

Reiner, H. D., & Hartshorne, T. S. (1982). Job burnout and the school psychologist. Psychology in the Schools, 19, 508–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034302023003233.

Reschly, D. J., & Connolly, L. M. (1990). Comparisons of school psychologists in the city and country: Is there a ‘rural’ school psychology? School Psychology Review, 19(4), 534–549. Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/publications/periodicals/spr/volume-19/volume-19-issue-4/comparisons-of-school-psychologists-in-the-city-and-country-is-there-a-rural-school-psychology.

Reschly, D. J., & Wilson, M. S. (1995). School psychology practitioners and faculty: 1986 to 1991-92 trends in demographics, roles, satisfaction, and system reform. School Psychology Review, 24(1), 62–80. Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/publications/periodicals/spr/volume-24/volume-24-issue-1/school-psychology-practitioners-and-faculty-1986-to-1991-92-trends-in-demographics-roles-satisfaction-and-system-reform.

Reschly, D. J. et al. (1987). The 1986 NASP Survey: Comparison of practitioners, NASP leadership, and university faculty on key issues (Technical Report No. 143). Retrieved from ERIC.

Rochester-Olang, S. D. (2011). The efficacy of psychological service delivery during organizational change processes within a department of education (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from Sociological Abstracts. (Order No. AAI3457765).

Sandoval, J. (1993). Personality and burnout among school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 30, 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199310)30:4%3C321::AID-PITS2310300406%3E3.0.CO;2-J.

Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L., & the PRISMA-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis-revised method (PRISMA-R): Elaboration and explanation. The British Medical Journal, 344, 1–25.

Smith, D. K., & Lyon, M. A. (1985). Consultation in school psychology: Changes from 1981 to 1984. Psychology in the Schools, 22, 404–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(198510)22:4%3C404::AID-PITS2310220409%3E3.0.CO;2-S.

Society for Human Resource Management. (2016). Average Cost-per-Hire for Companies Is $4,129, SHRM Survey Finds. Retrieved from https://www.shrm.org/about-shrm/press-room/press-releases/pages/human-capital-benchmarking-report.aspx.

Solly, D. C., & Hohenshil, T. H. (1986). Job satisfaction of school psychologists in a primarily rural state. School Psychology Review, 15(1), 119–126. Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/publications/periodicals/spr/volume-15/volume-15-issue-1/job-satisfaction-of-school-psychologists-in-a-primarily-rural-state.

The Conference Board. (2017, September 1). Job Satisfaction 2017 Edition/The Conference Board. Retrieved from https://www.conference-board.org/press/pressdetail.cfm?pressid=7184.

Thielking, M., Moore, S., & Jimerson, S. R. (2006). Supervision and satisfaction among school psychologists: An empirical study of professionals in Victoria, Australia. School Psychology International, 27(4), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034306070426.

Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4(3), 356–367 http://dx.doi.org.library.georgian.edu:2048/10.1177/1534484305278283.

Torraco, R. J. (2016). Writing integrative literature reviews: Using the past and present to explore the future. Human Resource Development Review, 15(4), 404–428 http://dx.doi.org.library.georgian.edu:2048/10.1177/1534484316671606.

Unruh, S., & McKellar, N. A. (2013). Evolution, not revolution: School psychologists’ changing practices in determining specific learning disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 50(4), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21678.

VanVoorhis, R. W., & Levinson, E. M. (2006). Job satisfaction among school psychologists: A meta-analysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 21(1), 77–90. http://dx.doi.org.library.georgian.edu:2048/10.1521/scpq.2006.21.1.77.

Weaver, A. D., & Allen, J. A. (2017). Emotional labor and the work of school psychologists. Contemporary School Psychology, 21, 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0121-6.

Whitley, B. E., & Kite, M. E. (2013). Principles of Research in Behavioral Science (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Williams, K. J., & Williams, G. M. (1990). The relation between performance feedback and job attitudes among school psychologists. School Psychology Review, 19(4), 550–563 Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/publications/periodicals/spr/volume-19/volume-19-issue-4/the-relation-between-performance-feedback-and-job-attitudes-among-school-psychologists.

Wilson, M. S., & Reschly, D. J. (1995). Gender and school psychology: Issues, questions, and answers. School Psychology Review, 24(1), 45–61 Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/publications/periodicals/spr/volume-24/volume-24-issue-1/gender-and-school-psychology-issues-questions-and-answers.

Worrell, T. G., Skaggs, G. E., & Brown, M. B. (2006). School psychologists’ job satisfaction: A 22-year perspective in the USA. School Psychology International, 27(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034306064540.

Wright, D., & Gutkin, T. B. (1981). School psychologists’ job satisfaction and discrepancies between actual and desired work functions. Psychological Reports, 49, 735–738. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1981.49.3.735.

Wright, D., & Thomas, J. (1982). Role strain among school psychologists in the Midwest. Journal of School Psychology, 20(2), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4405(82)90002-4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, T.J., Sobel, D. School Psychologists’ Job Attitudes: A Systematic Review. Contemp School Psychol 25, 40–50 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-019-00241-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-019-00241-4