Abstract

In school contexts, social support refers to the overall perception one has of feeling included and cared for in a community of peers, teachers, caregivers, and others. Social support is critical for promoting positive academic and psychosocial outcomes for students. Conversely, a lack of perceived social support may be associated with increased levels of psychological distress. The present review article describes critical considerations for providing social support to school-aged children and adolescents as well as presents a range of evidence-based strategies for increasing this type of support in schools. Interventions include academic, behavioral, and mental health services that are organized within a multitier framework of service delivery. Accordingly, these interventions address student needs at the universal, targeted, and indicated levels of support. The current level of empirical support is indicated for each described intervention. Overall, the implementation of a continuum of increasingly intensive approaches to promote social support in schools can be utilized to help make school environments more welcoming, positive, and emotionally supportive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Students encounter a variety of academic and social challenges in school. For younger students, these challenges typically relate to developing foundational academic competencies, understanding social norms, and learning to interact cooperatively with others (Ladd 1990). As they progress through school, students are expected to develop advanced academic and critical thinking skills, forge reciprocal relationships with friends, and make healthy lifestyle choices (Lane et al. 2003). Although developmentally normal, these adjustments may be particularly challenging and stressful, especially for students who are socially disconnected or have few supportive relationships (Blum 2005). Conversely, students who feel supported by their teachers, peers, and caregivers are particularly resilient to the challenges and stressors associated with adjusting to increasingly complex academic and social environments (Garcia-Reid et al. 2005; Wang and Eccles 2012). Thus, social support has an integral relationship with student development, adjustment, and success.

Definition of Social Support

Social support is defined as the overall “perception one has of being cared for, valued, and included by others within a network of caregivers, teachers, peers, and community members” (Saylor and Leach 2009, p. 71). More specifically, it refers to the array of interpersonal, psychosocial, and material resources available to individuals that enhance their functioning or buffer against adverse outcomes (Cohen 2004; Demaray and Malecki 2003). In schools, students receive social support from a number of sources including peers, teachers, and other school personnel. Children and adolescents also receive social support from caregivers, relatives, friends, and others who have a significant impact on their psychosocial functioning in a variety of settings.

Over the past few decades, numerous models and definitions of social support have been proposed (e.g., Cobb 1976; Williams et al. 2004). While these models differ to some extent, many are alike in their conceptualization of social support as a multidimensional construct that comprises multiple subtypes. For example, Tardy’s (1985) widely influential model subdivided the construct of social support into the following components: emotional support, instrumental support, informational support, and appraisal support. Emotional support involves having emotional attachments and feeling cared for by others, whereas instrumental support involves being the recipient of time and various supportive resources (e.g., materials and homework assistance; Tardy 1985). Informational support typically involves receiving helpful advice or information and appraisal support involves receiving evaluative feedback. Each form of social support can be provided by various individuals in a student’s social network, and these forms collectively confer a number of benefits to recipients (Malecki and Demaray 2003).

Social support from teachers, peers, and caregivers is vital to student success (Rosenfeld et al. 2000). Research indicates that students with higher levels of social support perform better academically, have better psychosocial outcomes, and display greater resilience when coping with challenging or adverse circumstances (Crean 2004; Garcia-Reid et al. 2005; Malecki and Demaray 2003). This article reviews the literature illustrating the importance of providing students with social support as well as factors that influence its provision in school settings. Additionally, a multilevel model is provided for increasing social support for students who display varying levels of need. This framework parallels a public health service delivery model and specifies interventions for students at universal, targeted, and indicated levels of service delivery. It expands upon previous frameworks (e.g., Demaray and Malecki 2014) by describing the amount of empirical support available for a range of interventions at each service delivery level. Finally, recommendations for structuring and implementing interventions and programs that aim to improve social support in schools also are provided.

The Importance of Social Support: Evaluating Student Outcomes

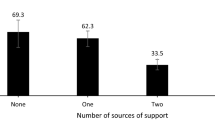

Receiving various forms of social support from caregivers, teachers, and peers is particularly important for promoting positive academic outcomes. In this vein, students who feel supported by their teachers and peers tend to be engaged in their coursework and the school environment as well as to display strong academic initiative (Garcia-Reid et al. 2005; Wang and Eccles 2012). Moreover, students who feel supported by caregivers, friends, and teachers tend to have higher school attendance rates, receive higher grades, and spend more hours studying than do students who feel supported by none or only one or two of these sources (Rosenfeld et al. 2000).

Teacher, caregiver, and peer support is positively related to a range of favorable psychosocial outcomes for students, including having a healthier self-concept and higher levels of self-esteem (Chu et al. 2010). Perceived emotional support from teachers also is positively associated with students’ degree of social competence, and several studies have identified caregiver and classmate support as important predictors of psychosocial adjustment (Demaray et al. 2005; Malecki and Demaray 2003). Conversely, a lack of perceived social support from peers, caregivers, and others may be related to increased psychological distress including symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other emotional problems (Demaray et al. 2005; Rueger et al. 2010). For example, victims of peer aggression tend to experience a range of adverse social and emotional outcomes, including poor psychosocial adjustment, maladaptive coping, social isolation, and suicidal behavior (Brunstein Klomek et al. 2008; Glew et al. 2005; Schwartz et al. 2005; Sulkowski et al. 2014).

In addition to being associated with favorable psychosocial adjustment, social support also is an important protective factor for preventing negative psychosocial adjustment (Nettles et al. 2000). Higher levels of social support are associated with more adaptive coping skills, which in turn are positively related to students’ degree of academic and social competence (Crean 2004). Moreover, research indicates that the negative effects of peer victimization on students’ quality of life are mediated by their perceived level of social support (Flashpohler et al. 2009).

Importantly, the absence of perceived social support often has dire consequences. For example, in a sample of high school dropouts, only 41 % of students reported that there was someone at school that they could talk to regarding a personal problem, and only 56 % had a school staff member they could talk to about a school-related concern (Bridgeland et al. 2006). In addition, the most frequently cited reason for leaving school among students who have dropped out is a lack of perceived support from school personnel (Kortering and Braziel 2002). Collectively, these findings highlight the important links between social support and students’ psychosocial functioning, academic performance, and long-term outcomes.

Developmental Considerations in Providing Social Support

The influence of various types of social support (e.g., teacher, peer, and caregiver) appears to change over time. Children in elementary school often select their caregivers before their friends when they are asked with whom they would like to spend most of their time (Nickerson and Nagle 2005). However, an age-related interaction exists between these two choices. During middle school, students frequently prefer to spend time with friends over their caregivers, although they often still identify their caregivers as important sources of emotional support (Malecki and Demaray 2003; Nickerson and Nagle 2005). By age 16, however, youth often perceive that their friends are more supportive than their caregivers are (Bokhorst et al. 2009). For older students, the prominent role of peer support may be attributable to adolescents’ increased psychological maturity and capacity to provide emotional support to their peers (Bokhorst et al. 2009).

Perceived levels of teacher support may also change with age. A study by Bokhorst et al. (2009) found that younger students (ages 9–12) perceive more social support from teachers than do older students (ages 13–18). In this study, older students reported that classmates and caregivers were greater sources of social support than their teachers were. Similarly, Malecki and Demaray (2002) found that perceived teacher support decreases as grade level increases. A decline in perceived teacher support over time is likely attributable to the transition to secondary school, which typically involves adjusting to a larger student body, casual interactions with multiple instructors, and other factors that can attenuate the quality of teacher-student relationships (Bokhorst et al. 2009; DeWit et al. 2011).

The coordination of age-appropriate prevention and intervention efforts should consider how perceived social support changes as students progress through school. More specifically, intervention efforts should consider who should be involved in prevention and intervention efforts for students of different ages (Bokhorst et al. 2009). For example, school leaders and personnel can make a concerted effort to connect students with educators when they enter secondary school. In this regard, tutoring, small group work, enriching class discussions, and cooperative learning activities can help students to connect with educators and other school community members (Barker et al. 1997; Korinek et al. 1999; Schaps and Solomon 1990).

Considerations for Providing Social Support to Students from Diverse Backgrounds

Individual differences in socioeconomic status (SES), gender, culture, race, and ethnicity also may impact the influence of social support on students. More specifically, these factors may be important to consider when structuring interventions because they can influence the way social support is perceived, sought, and received in school settings. For example, a study by Malecki and Demaray (2006) found that the relationship between SES and academic performance is moderated by perceived support from caregivers and classmates. Specifically, levels of perceived social support from caregivers and classmates predicted grade point averages for low SES students. However, research is needed to clarify the influence of social support on student outcomes for individuals from different SES backgrounds.

Compared to literature on the interaction between SES and social support, relatively more is known about how gender influences social support. Several studies indicate that girls perceive higher levels of social support from a variety of sources, especially classmates and peers, when compared with same-age boys (e.g., Bokhorst et al. 2009; Rueger et al. 2008, 2010). Moreover, perceived levels of social support may impact behavior and emotional well-being differently between genders. For example, perceived level of global support (i.e., combined support from parents, teachers, and peers) is a significant predictor of internalizing behavior for boys (e.g., depression, anxiety), whereas it is more related to externalizing behaviors for girls (e.g., hyperactivity, oppositional/defiant behaviors; Rueger et al. 2008). However, despite these differences, access to social support is critical to promoting positive outcomes for both males and females in aggregate, especially during adolescence when students tend to prioritize their social connections.

In addition to SES and gender, cultural factors are important to consider when designing interventions to increase social support. Culture (i.e., the collective attitudes, behavioral patterns, beliefs, and values shared by individuals from a particular background) can influence the way in which children and adolescents perceive their relationships with friends, family members, and teachers as well as the way they access networks of support (Goebert 2009). For example, in individualistic cultures, relationships are believed to be freely chosen, and individuals are encouraged to express their concerns and needs to significant others. However, in collectivist cultures, relationships tend to be more interdependently oriented, and individuals often view their interpersonal relationships as obligations to a greater community or extended family system (Oyserman and Lee 2008). Subsequently, individuals in collectivist cultures may be more hesitant to seek support when stressed because of concerns about potentially upsetting interpersonal dynamics (Goebert 2009). For example, research has shown that individuals from Asian cultures (which often are characterized by more collectivist values) are less likely to seek social support during stressful times than individuals from European American backgrounds (which tend to emphasize more individualistic values; Taylor et al. 2004). Additionally, cultural factors also may impact students’ choices about from whom they seek support. For example, family relations traditionally are characterized by strong feelings of commitment and loyalty and are regarded as critical sources of support in Hispanic and Latino cultures (Fuligni et al. 1999). Therefore, efforts to improve social support for students of these backgrounds may be optimized by reaching out to family members and including them in intervention programming (Garcia-Reid et al. 2005).

When designing interventions to increase social support for students who are racial and ethnic minorities, school personnel also may need to consider unique stressors such as discrimination, alienation, and acculturative stress, which can impact their social interactions. Fortunately, research indicates that social support can be an effective buffer against the adverse effects of these stressors. For example, peer social support has been found to be more strongly associated with school identification and school engagement among African American students than it has for European American students, indicating that strong peer relations may be a critical protective factor for African American students (Wang and Eccles 2012). Moreover, Garcia-Reid et al. (2005) found that social supports provided to Latino students by their parents, teachers, and friends were positively associated with school engagement.

Overall, findings on the influence of various demographic variables on the perception and receipt of social support highlight the importance of tailoring interventions for a range of students, particular populations, and heterogeneous educational environments. The process of adapting and implementing culturally responsive interventions in schools is complex and may involve assessing the acculturation style of students, altering the use of microskills (i.e., observable communicative skills in clinical practice) to accommodate clients’ relational styles, involving families in intervention planning and delivery, and implementing a strengths-based approach (i.e., one that capitalizes on the existing strengths and supports within a given cultural group or community; Jones 2014). In the following, a multilevel service delivery model for supporting students who display a continuum of diverse social needs is introduced. This model aims to provide social support at universal, targeted, and indicated levels of service delivery.

Providing Social Support to Students: a Multilevel Service Delivery Model

Over the past decade, multilevel service delivery models that allow school systems to match intervention intensity or dose to students’ needs have emerged. These school-based multilevel models parallel a variegated public health model of prevention and intervention that specifies three layers of service delivery: primary (universal), secondary (targeted), and tertiary (indicated) intervention levels. Similarly, they overlap with response-to-intervention (RTI) service delivery models for addressing students’ academic, behavioral, and mental health needs (Fletcher and Vaughn 2009; Sulkowski and Michael 2014; Sulkowski et al. 2011; Wodrich et al. 2006). Interventions often are hierarchically arranged to correspond with student needs universally, in small groups (targeted), and individually (indicated) in multilevel models of service provision. Moreover, these hierarchical service delivery models presuppose that fewer students will need services at higher or more intense levels of intervention.

In multilevel models, universally provided (i.e., provided to all students) prevention and intervention services aim to promote positive outcomes and to prevent academic, behavioral, and psychosocial problems. Targeted interventions are provided to a subset of at-risk students who display emerging problems or vulnerabilities yet still do not display a need for intensive interventions or individualized support. These secondary services typically are delivered in a group-based format and are designed to build students’ social-emotional resources and competencies (e.g., emotional regulation and coping skills). Moreover, they often entail documented progress monitoring (Sulkowski et al. 2011). Finally, in most hierarchical service delivery models, indicated or tertiary interventions are the most intensive and specialized intervention types that can be provided as a result of or independently from receiving a diagnosis of a disability or as recognized under the Individuals with Disabilities Educational Improvement Act (IDEIA). Ideally, these interventions are research-based, highly structured, and are delivered in individualized or one-on-one settings.

Demaray and Malecki (2014) described the assessment and provision of social support to students within a multitiered system of service delivery. At the universal (tier 1), targeted (tier 2), and indicated (tier 3) levels, they reviewed a range of school-wide programs designed to promote social and emotional learning (SEL) as well as group and individualized counseling, mentoring, and social skills interventions. As the authors acknowledge, many interventions that are likely to increase social support are not designed specifically or exclusively for this purpose; rather, they are designed to build students’ social and emotional competencies and to improve school climate. In implementing these interventions, schools have considerable flexibility in adapting them to address student needs across different levels of service delivery. For example, school psychologists may use components of a group-delivered social skills program (e.g., affect recognition, problem solving) with students in one-on-one settings (i.e., at the indicated level of support). However, intervention services generally are provided in a hierarchical manner ranging from the least to most intensive in terms of time and needed resources. Thus, although not rigidly fixed, a general framework often guides the provision of intervention services in schools.

In the following, a multilevel service delivery framework is described that may assist school-based personnel in providing social support to students. This framework includes instructional strategies, mental health services, and behavioral supports that may be implemented at the universal, targeted, and indicated levels. Further, empirical support and gaps in literature are discussed for interventions at each level of service provision. Table 1 lists interventions that may improve students’ social support, the degree of available empirical support for these interventions, as well as representative publications.

Universal Interventions

Two interrelated goals of universal interventions are to enhance overall school climate and to foster positive relationships among all members of school communities (Demaray and Malecki 2014). At the systems level, these interventions may involve enhancing school infrastructure to facilitate effective communication and collaboration among students, teachers, and caregivers. Universal school-level interventions may also aim to improve students’ ability to engage in healthy and meaningful exchanges with their peers and teachers. In this regard, various school-wide interventions can enhance school climate and help foster positive relations in school systems such as SEL initiatives, school-wide positive behavior supports, violence and bullying prevention programs, strong home-school partnerships, and instructional practices that promote cooperative learning. In selecting appropriate universal initiatives, practitioners and administrators may first review a range of school-wide data (e.g., academic data, office discipline referrals, and attendance records) to identify specific areas of need within their respective student populations.

Social and Emotional Learning

Social and emotional learning refers to the process of acquiring core competencies in recognizing and regulating emotions, setting and working toward positive goals, initiating and maintaining positive relationships, and developing other prosocial behaviors (Durlak et al. 2011). Social and emotional learning programs can help increase social support because of their emphasis on communication, cooperation, and relationship-building skills (Sulkowski et al. 2012a). More specifically, as the most widely known and empirically supported resource for SEL programs, the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL 2003) identifies five core skill areas that comprehensive SEL programs target: self-awareness (i.e., understanding of one’s emotions and behaviors), social awareness (i.e., perspective-taking and interacting positively with diverse individuals), self-management (i.e., regulating emotions and goal setting), relationship skills (i.e., developing healthy and meaningful connections with others), and decision-making (i.e., considering relevant information and making positive choices).

With these skill areas in mind, well-designed SEL programs are theoretically grounded, empirically supported, and involve the use of systematic, explicit, and developmentally appropriate instructional techniques. Additionally, these programs encourage students to apply and generalize acquired skills across multiple settings (CASEL 2003). Examples of empirically supported SEL programs include the Caring School Community (Battistich et al. 2004), I Can Problem Solve (Boyle and Hassett-Walker 2008; Shure 2001), Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (Bierman et al. 2010; Kusche and Greenberg 1994), and Social Decision-Making and Problem-Solving programs (Elias et al. 1986). In general, meta-analytic research on SEL programs suggests that they promote prosocial behaviors as well as positively impact students’ attitudes toward themselves, others, and school as well as increase competence in core academic areas by 10 to 11 percentile points on standardized tests (Durlak et al. 2011).

School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

Implementation of school-wide positive behavior support (SWPBS) systems may increase social support by fostering prosocial attitudes and behaviors among students as well as by improving the overall social culture of schools. Broadly defined, SWPBS is a systems approach to preventing and changing patterns of problem behavior through the establishment of safe and positive learning environments (Sugai and Horner 2006). Typically, SWPBS models consist of both universal and individualized behavioral supports for students. At the universal level, these supports involve establishing school-wide expectations for positive/prosocial behavior, explicitly teaching behavioral expectations and prosocial behaviors, clearly defining procedures for acknowledging and rewarding appropriate behavior, and adopting a codified approach to discipline. A number of studies have indicated that SWPBS implementation is associated with reductions in bullying, peer rejection, and disciplinary problems (e.g., office discipline referrals and school suspensions; Metzler et al. 2001; Waasdorp et al. 2012). Moreover, implementation of these frameworks is related to increased levels of perceived safety in the school environment (Horner et al. 2009). Thus, SWPBS may enhance social support by promoting prosocial interactions among students as well as by improving school climate.

Violence and Bullying Prevention

Similar to SEL initiatives, school-wide programs designed specifically to prevent peer victimization and violence may improve school climate and increase levels of perceived social support in school communities. As the most comprehensive review to date, the Task Force on Community Preventive Services conducted a systematic review of 53 published scientific studies concerning the effectiveness of universal school-based programs designed to decrease violent and aggressive behavior among school-aged children (Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2007). As a central theme, these programs teach all students in a school grade or school about the impact of violence and its prevention or about one or more of the following topics or skills intended to reduce aggressive or violent behavior: emotional self-awareness, emotional control, self-esteem, positive social skills, conflict resolution, social problem solving, and team work. Results of this analysis indicate that program effects were demonstrated at all grades at the aggregate level. In addition, a second independent meta-analysis of school-based programs confirmed and supplemented these results (Hahn et al. 2007). As a result of these findings, the Task Force recommends the use of universal school-based programs to prevent or reduce violent behavior.

Some well-known and commercially available effective violence prevention programs currently are being implemented in many school systems. For example, Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum has shown considerable promise in promoting students’ social competence (Grossman et al. 1997; McMahon and Washburn 2003). Second Step is designed to reduce social, emotional, and behavioral problems by building students’ skills in the areas of empathy, social problem solving, and anger management (Committee for Children 1997). Research on the effectiveness of this program suggests that it reduces aggressive and antisocial behaviors as well as improves students’ skills in coping with peer aggression (Edwards et al. 2005; Frey et al. 2005b). This curriculum also has been found to increase students’ knowledge of social skills and their social competence (McMahon et al. 2000; Taub 2002). Thus, violence prevention programs may influence social support by teaching students skills that can help them empathize, support, and connect with others.

In addition to aggression/violence prevention programs, bullying prevention programs such as the Olweus Bully Prevention Program (OBPP; Olweus et al. 1999) are designed to improve social environments through encouraging the development of healthy relationships among peers, establish and uphold firm expectations for student behavior, and increase the presence and involvement of positive adult role models in school communities (Olweus and Limber 2010). Although several investigations indicated that the OBPP successfully reduced incidents of relational and physical aggression in elementary schools throughout the USA (e.g., Black and Jackson 2007; Limber 2004), subsequent studies have not replicated these results in culturally diverse settings (Bauer et al. 2007). Thus, additional research is needed to investigate how elements of culture, language, and socialization collectively impact peer aggression as well as how reducing peer aggression can positively affect social support in schools. However, Frey et al. (2009) have implemented the Steps to Respect antibullying program on school playgrounds and have shown that children receiving an active intervention displayed a reduction in playground bullying, victimization, nonbullying aggression, and destructive bystander behavior. Further, the Steps to Respect antibullying program also has been associated with enhanced bystander responsibility, greater perceived adult responsiveness, and less acceptance of bullying and aggression (Frey et al. 2005a, b).

Home-School and Community Partnerships

Universal efforts to enhance social support also can incorporate strategies to improve home-school collaboration. Establishing home-school partnerships involves forming integrated networks of caregivers, educators, and others who are invested in students’ success. Research suggests that teacher support alone is not sufficient to promote positive behavioral and academic outcomes (e.g., higher achievement and levels of school satisfaction) and that it should be accompanied by support from parents and others (Rosenfeld et al. 2000). Essential features of effective home-school partnerships include establishing regular, diversified, and accessible channels of communication between families and schools, shared decision-making and goal setting, and ongoing discussion and role clarification among individuals involved in facilitating a child’s educational success (Cox 2005). To facilitate effective home-school partnerships, the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP 2005) offers recommendations for increasing family participation in school-related activities in a position statement on home-school collaboration. These recommendations involve inviting caregivers to serve as volunteers and committee members, encouraging them to monitor homework completion, and inviting them to attend and participate in school functions (e.g., events for extracurricular activities). However, it should be noted that caregiver involvement is only one feature of effective home-school partnerships that involve a range of comprehensive, consistent, and collaborative efforts between schools and families (Cox 2005). Ultimately, it is the responsibility of schools to create conditions that allow for effective and meaningful communication between educators and families, as a variety of barriers may discourage caregivers from initiating contact (e.g., cultural and linguistic barriers, time and scheduling constraints; Reschly and Christenson 2012). Promising intervention programs and strategies such as the Incredible Years (Reid et al. 2003; Webster-Stratton et al. 2004) and Joint Behavioral Consultation (Sheridan et al. 2001; Sheridan and Kratochwill 2007) provide well-defined frameworks for involving caregivers in service delivery and decision-making for their children (Reschly and Christenson 2012).

In addition to home-school partnerships, community partnerships also may be important for creating safe and supportive school environments. Partnering with community agencies affords school personnel increased access to resources as well as opportunities to coordinate service delivery across multiple settings. School-community partnerships may be established to support students’ development in a variety of areas, including academic, behavioral, social, and emotional domains (Eagle and Dowd-Eagle 2014). For example, there is some evidence to suggest that programs such as Big Brothers Big Sisters and Boys and Girls Clubs show promise for fostering healthy relationships with peers and family members, decreasing substance use, and encouraging school attendance (Anderson-Butcher et al. 2003; Grossman and Tierney 1998; St. Pierre et al. 2001). Forging effective and sustainable partnerships requires school and community members to work collaboratively to clarify intervention goals, recognize and merge their strengths, and develop and evaluate programs that effectively target student needs (Eagle and Dowd-Eagle 2014).

Instructional Practices

Social support can be enhanced by implementing instructional practices that aim to increase meaningful teacher-student and peer interactions (Roseth et al. 2008). For example, improved teacher-student relations as well as increased student satisfaction and morale have been found to result from block scheduling, in which fewer and longer class periods are scheduled for each school day (Biesinger et al. 2008; Hurley 1997). However, subsequent research is needed to corroborate these findings and instructional practices that promote cooperative interactions at the classroom level may increase camaraderie and positive social interdependence among students (Roseth et al. 2008). Preliminary evidence suggests that peer-assisted learning (PAL), which includes cooperative learning and peer tutoring techniques, may improve social outcomes for students (e.g., foster the development of social skills; Ginsburg-Block et al. 2006). Specific examples of PAL strategies include think-pair-share, in which students individually consider a topic and then share their ideas with one or more partners, and the Jigsaw method, which involves having students first develop “expertise” in a given area and then share their knowledge with others (Sulkowski et al. 2012a, b). Peer-assisted learning strategies that involve reinforcing students for cooperating with others have been linked to positive student outcomes such as improved social skills and self-concept (Ginsburg-Block et al. 2006). Cooperative learning activities may also promote positive attitudes toward diversity and increase the frequency of interactions among students from different cultural backgrounds (Johnson and Johnson 1982). Peer-assisted learning is a promising approach for bolstering social support in classrooms; however, further research is needed to explore its effects on student performance across a variety of domains.

Other universal interventions that promote social support provide opportunities for students with common interests and experiences to interact and connect with each other. For example, extracurricular activities such as clubs and athletic teams provide opportunities for students to build networks of social support. In particular, they allow students to identify with similar and like-minded peers as well as to become part of interconnected communities.

Targeted Interventions

As previously described, targeted interventions are designed to support students who are at risk for negative long-term outcomes. Among other problems, students with low social support may be at risk for social isolation, peer victimization, anxiety, depression, and school dropout (Croninger and Lee 2001; Demaray and Malecki 2002; Demaray et al. 2005; Rigby 2000). Student support teams may identify individuals as needing targeted interventions based on a variety of data, including universal screenings of social, emotional, and behavioral functioning (e.g., Behavioral and Emotional Screening System; Kamphaus and Reynolds 2007) as well as attendance and discipline referral records. Individuals who are considered to be at risk may be referred for group-based supports provided by a range of personnel, including school psychologists, clinical social works, guidance counselors, and other mental health and student support staff.

One example of a targeted social support intervention is peer mentoring. This intervention often involves pairing younger and less experienced students with older and more experienced students who guide and support the mentees’ academic, social, and emotional development (Garringer and MacRae 2008). Peer mentoring has been found to increase feelings of school connectedness for both mentors and mentees as well as to facilitate the development of prosocial behaviors and attitudes in mentees (Karcher 2005, 2007, 2009). Effective mentors often are older students (preferably high school age) who exhibit good judgment and high levels of social engagement and empathy. Following adequate training, peer mentors can engage their mentees in personal growth activities covering a variety of topics such as goal setting, recognizing and responding to bullying and peer pressure, problem solving and conflict resolution, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle (Garringer and MacRae 2008).

Group-Based Treatments

Social skills training programs also can be implemented as targeted interventions to increase social support in schools. These programs can be delivered in individual or small-group formats to increase students’ ability to initiate and maintain relationships, engage in reciprocal social behaviors, and express concern and empathy for others. Programs such as the Coping Power Program (Lochman and Wells 2002a) can be provided to groups of students who are at risk for aggression, peer relational problems, and poor social outcomes. The Coping Power Program has been found to improve children’s social competence and reduce their aggressive and delinquent behaviors as well as substance use and abuse (Lochman and Wells 2002b, 2003; Lochman et al. 2009).

As another targeted group-based intervention, social anxiety treatment groups can be implemented in school settings. Youth with untreated social anxiety are at risk for experiencing depression, other anxiety problems, and substance abuse in adolescence and adulthood in addition to reporting less social acceptance and support from their peers (Kendall et al. 2004; LaGreca and Lopez 1998). Group-based cognitive-behavioral treatments for social anxiety are particularly effective in mitigating social anxiety symptoms, possibly because group participating can be anxiety provoking in itself which allows students to experience and habituate to anxiety in a relatively safe and controlled environment (Masia et al. 2001; Masia-Warner et al. 2007). Additionally, members of school-based social anxiety groups can benefit from identifying with each other while providing others with support when necessary (Masia-Warner et al. 2005).

Although research on the efficacy of other group-based interventions for at-risk students is limited, many schools provide a range of these services as selective interventions. In this regard, friendship groups may help support some students with weak social connections. For example, the “Circle of Friends” intervention program aims to integrate vulnerable children into school communities, and it has been found to be effective for reducing peer exclusion and increasing the perceived social acceptance of participating students (Frederickson and Turner 2003; Taylor 1997). Other group-based interventions can support students with a range of vulnerabilities. For example, students who share common life experiences, such as transferring to a new school, immigrating to a different country, losing a family member, or having their parents separate, may feel supported by connecting and interacting with others who have had similar experiences. Lastly, for students who have been affected by natural disasters or other crises, small-group counseling sessions and support groups may provide a safe venue for discussing disaster-related and other potentially traumatic events as well as for developing coping and problem-solving skills (Lazarus et al. 2003). More specifically, school-based group counseling interventions for at-risk children may be particularly useful for normalizing their reactions to traumatic events and reinforcing the use of adaptive coping skills (Chemtob et al. 2002; Stein et al. 2003).

Indicated Interventions

Indicated interventions are provided to students with problems that are resistant to the effects of targeted interventions and they often involve the delivery of individualized services. Students may be identified as needing indicated interventions based on a review of progress monitoring and summative data collected during the delivery of targeted interventions (Sulkowski et al. 2011). These data may include periodic structured observations, work samples, and omnibus behavior rating scales, such as the Behavior Assessment System for Children, 2nd edition (BASC-2; Reynolds and Kamphaus 2004). They may also include single construct measures (e.g., Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale, second edition; Reynolds and Richmond 2008) as well as other norm-referenced progress monitoring measures that are sensitive to smaller, incremental changes in behavior and emotional well-being (e.g., BASC-2 Progress Monitor; Reynolds and Kamphaus 2009). Once identified as needing more intensive supports, students may receive interventions such as individualized therapy or counseling from a school-based mental health professional. Other types of supports may include “teacher as a mentor” programs. It should be noted that indicated interventions for increasing social support are likely to vary considerably across different school settings due to differences in personnel and the availability of resources.

Individualized Therapy

Students with symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders that negatively impact their social functioning may respond positively to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) or cognitive-behavioral interventions aimed at reducing these symptoms (Compton et al. 2004). Using CBT to treat symptoms of mood and anxiety disorders in children in school settings is a promising practice yet it is not a panacea. In a meta-analysis, small to moderately strong effects were found (ES = .20–.76) for indicated or tertiary school-based CBT programs that aimed to treat childhood anxiety (Neil and Christensen 2009). Thus, with regard to using CBT in schools, research is needed on ways to reduce barriers to obtaining robust treatment outcomes as well as ways to tailor and augment extant approaches to maximize their efficacy.

Recently, Khanna and Kendall (2008) developed Camp Cope-A-Lot (CCAL), an evidence-based and computer-assisted (i.e., involving a computer program and therapist) CBT program that is designed to treat childhood anxiety. This program includes six sessions that are computer driven and six sessions that involve confronting one’s fears with the help of a therapist. Results of a randomized controlled trial suggest that CCAL is equally as effective in reducing anxiety in children as typical manualized treatments are (Khanna and Kendall 2010). As a program that is highly transportable and can be easily implemented in school settings, CCAL displays promise in allowing many students to receive evidence-based treatments who traditionally do not (Sulkowski et al. 2011).

Teachers as Mentors

Feeling bonded or connected to at least one adult is associated with better psychosocial outcomes in youth (Resnick et al. 1993). Additionally, children who have supportive relationships with important adults also tend to have better peer relationships (Hughes et al. 2001). However, students with disruptive behavior disorders often have conflicted relationships and they may struggle to connect with adults (Tremblay 2000). To assist these at-risk youth, teachers and other school personnel can reach out and support these students. Results from a study by Hughes et al. (2001) suggest that interventions focusing on the affective quality of teacher-student interactions may improve both teacher and peer perceptions of students with disruptive behavior problems. Further, results of the former study imply that peers are more likely to view these children’s behaviors in a favorable light if they have supportive teacher-student interactions.

Although limited research exists on the specific ways that teachers can be mentors to at-risk students, ways that they can support these students often have intuitive appeal. For example, teachers can greet students by name as they enter the classroom, use active listening strategies when talking with students (e.g., make good eye contact, summarize and reflect), highlight and compliment their strengths, arrange for regular meetings, discuss shared or mutual interests, and openly express empathy and understanding. In general, having relationships with teachers that are characterized by warmth, mutual trust, and low degrees of conflict is associated with a range of positive school outcomes (Slicker and Palmer 1993; Baker et al. 2008). Further, efforts to mentor at-risk students are likely to improve these relationships.

Summary and Conclusions

Social support is critically important for promoting a range of positive academic, social, and emotional student outcomes. Unfortunately, less than a third (29 %) of 12th graders report that their school provides a caring and encouraging learning environment (Benson 2006) and more than 12 million students will drop out during the next decade (Rouse 2005). Collectively, these statistics highlight the importance of making schools more nurturing and socially-emotionally supportive. School personnel can cultivate social support for students by helping them to develop effective coping strategies, teaching social and emotional competencies, creating welcoming and nurturing learning environments, and building relationships with other community members that also influence children’s well-being. To accomplish these goals, a multilevel service delivery model can help guide the provision of interventions that aim to improve social support for students displaying a range of needs. For example, interventions can be provided broadly to all students (i.e., universal interventions), to students at risk for being disconnected to the school environment (i.e., targeted interventions), and to students who clearly display low levels of social support (i.e., indicated interventions). Within this framework, a variety of personnel may have integral roles in promoting safe and supportive learning environments. For example, school psychologists, teachers, guidance counselors, and others may be called upon to assist with data collection, deliver interventions, monitor student behavior, and coordinate school-wide prevention initiatives.

As reviewed, a number of empirically supported or established interventions exist for providing students with social support. However, further research is needed on emerging and promising interventions that may have intuitive appeal and already may be widely applied yet warrant empirical validation. As implied by the multilevel service delivery model described above, schools can provide a range of research-based interventions to improve social support that are compatible with their existing infrastructure and resources or that involve making a few modifications to extant policies and practices. Similarly, at the individual level, school-based mental health practitioners can promote student success by increasing their efforts to create welcoming school communities that center on supportive student, teacher, and peer relationships.

References

Anderson-Butcher, D., Newsome, W. S., & Ferrari, T. M. (2003). Participation in Boys and Girls Clubs and relationships to youth outcomes. Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 39–53. doi:10.1002/jcop.10036.

Baker, J. A., Grant, S., & Morlock, L. (2008). The teacher-student relationship as a developmental context for children with internalizing or externalizing behavior problems. School Psychology Quarterly, 23, 3–15. doi:10.1037/1045-3830.23.1.3.

Barker, J. A., Terry, T., Bridger, R., & Winsor, A. (1997). Schools as caring communities: a relational approach to school reform. School Psychology Review, 26, 586–603.

Battistich, V., Schaps, E., & Wilson, N. (2004). Effects of an elementary school intervention on students’ “connectedness” to school and social adjustment during middle school. Journal of Primary Prevention, 24, 243–262. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08286x.

Bauer, N. S., Lozano, P., & Rivara, F. P. (2007). The effectiveness of the Olweus bullying prevention program in public middle schools: a controlled trial. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 266–274. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.005.

Benson, P. L. (2006). All kids are our kids: what communities must do to raise caring and responsible children and adolescents (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bierman, K. L., Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., Greenberg, M. T., Lochman, J. E., McMahon, R. J., & Pinderhughes, E. (2010). The effects of a multiyear universal social-emotional learning program: the role of student and school characteristics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 156–168. doi:10.1037/a0018607.

Biesinger, K. D., Crippen, K. J., & Muis, K. R. (2008). The impact of block scheduling on student motivation and classroom practices in mathematics. NASSP Bulletin, 92, 191–208. doi:10.1177/0192636508323925.

Black, S. A., & Jackson, E. (2007). Using bullying incident density to evaluate the Olweus Bullying Prevention Programme. School Psychology International, 28, 623–638. doi:10.1177/0143034307085662.

Blum, R. W. (2005). A case for school connectedness. Educational Leadership, 62, 16–20.

Bokhorst, C., Sumter, S., & Westenberg, M. (2009). Social support from parents, friends, classmates, and teachers in children and adolescents aged 9 to 18 years: who is perceived as most supportive. Social Development, 19, 417–426. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00540.x.

Boyle, D., & Hassett-Walker, C. (2008). Reducing overt and relational aggression among young children: the results from a two-year outcome evaluation. Journal of School Violence, 7, 27–42. doi:10.1300/J202v07n01_03.

Bridgeland, J. M., DiIulio, J. J., & Morison, K. B. (2006). The silent epidemic. Perspectives of high school dropouts. Washington: Civic Enterprises and Peter D. Hart Research Associates for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Brunstein Klomek, A., Marrocco, F., Kleinman, M., Schonfeld, I. S., & Gould, M. S. (2008). Peer victimization, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 38, 166–180. doi:10.1521/suli.2008.38.2.166.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). The effectiveness of universal school-based programs for the prevention of violent and aggressive behavior. A report on recommendations of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 56, 1–16.

Chemtob, C. M., Nakashima, J. P., & Hamada, R. S. (2002). Psychosocial intervention for postdisaster trauma symptoms in elementary school children: a controlled community field study. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 156, 211–216. doi:10.1001/archpedi.156.3.211.

Chu, P. S., Saucier, D. A., & Hafner, E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29, 624–645.

Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38, 300–314.

Cohen, S. (2004). Social relationships and health. American Psychologist, 59, 676–684. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (2003). Safe and sound: an educational leader’s guide to evidence-based social and emotional learning (SEL) programs. Chicago: Author.

Committee for Children (1997). Second Step: a violence prevention curriculum; middle school/junior high. Seattle: Author.

Compton, S. N., March, J. S., Brent, D., Albano, A. M., Weersing, V. R., & Curry, J. (2004). Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: an evidence-based medicine review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 930–959. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000127589.57468.bf.

Cox, D. D. (2005). Evidence-based interventions using home-school collaboration. School Psychology Quarterly, 20, 473–497. doi:10.1521/scpq.2005.20.4.473.

Crean, H. F. (2004). Social support, conflict, major life stressors, and adaptive coping strategies in Latino middle schools students: an integrative model. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 657–676. doi:10.1177/0743558403260018.

Croninger, R. G., & Lee, V. E. (2001). Social capital and dropping out of school: benefits to at-risk students of teachers’ support and guidance. Teachers College Record, 103, 548–581.

Demaray, M. K., & Malecki, C. K. (2002). The relationship between perceived social support and maladjustment for students at risk. Psychology in the Schools, 39, 305–316. doi:10.1002/pits.10018.

Demaray, M. K., & Malecki, C. K. (2003). Importance ratings of socially supportive behaviors by children and adolescents. School Psychology Review, 32, 108–131.

Demaray, M. K., & Malecki, C. K. (2014). Best practices in assessing and promoting social support. In P. L. Harrison & A. Thomas (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology: student-level services (pp. 239–249). Bethesda: National Association of School Psychologists.

Demaray, M. K., Malecki, C. K., Davidson, L. M., Hodgson, K. K., & Rebus, P. J. (2005). The relationship between social support and student adjustment: a longitudinal analysis. Psychology in the Schools, 42, 691–706. doi:10.1002/pits.20120.

DeWit, D., Karioja, K., Rye, B., & Shain, M. (2011). Perceptions of declining classmate and teacher support following the transition to high school: potential correlates of increasing student mental health difficulties. Psychology in the Schools, 48, 556–572. doi:10.1002/pits.20576.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82, 405–432. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x.

Eagle, J., & Dowd-Eagle, S. E. (2014). Best practices in school-community partnerships. In P. L. Harrison & A. Thomas (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology: systems-level services (pp. 197–210). Bethesda: National Association of School Psychologists.

Edwards, D., Hunt, M., Meyers, J., Grogg, K., & Jarrett, O. (2005). Acceptability and student outcomes of a violence prevention curriculum. Journal of Primary Prevention, 26, 401–418. doi:10.1007/s10935-005-0002-z.

Elias, M. J., Gara, M., Ubriaco, M., Rothbaum, P. A., Clabby, J. F., & Schuyler, T. (1986). Impact of a preventive social problem solving intervention on children’s coping with middle-school stressors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 259–275.

Flashpohler, P. D., Elfstrom, J. L., Vanderzee, K. L., Sink, H. E., & Birchmeier, Z. (2009). Stand by me: the effects of peer and teacher support in mitigating the impact of bullying on quality of life. Psychology in the Schools, 46, 636–649. doi:10.1002/pits.20404.

Fletcher, J. M., & Vaughn, S. (2009). Response to intervention: preventing and remediating academic difficulties. Child Development Perspectives, 3, 30–37. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00072.x.

Frederickson, N., & Turner, J. (2003). Utilizing the classroom peer group to address children’s social needs: an evaluation of the Circle of Friends intervention approach. Journal of Special Education, 36, 234–245. doi:10.1177/002246690303600404.

Frey, K. S., Hirschstein, M. K., Snell, J. L., Van Schoiack Edstrom, L., MacKenzie, E. P., & Broderick, C. J. (2005a). Reducing playground bullying and supporting beliefs: an experimental trial of the Steps to Respect program. Developmental Psychology, 41, 479–490. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.41.3.479.

Frey, K. S., Nolen, S. B., Van Schoiack-Edstrom, L., & Hirschstein, M. K. (2005b). Effects of a school-based social-emotional competence program: linking children’s goals, attributions, and behavior. Applied Developmental Psychology, 26, 171–200. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2004.12.002.

Frey, K. S., Hirschstein, M. K., Van Schoiack Edstrom, L., & Snell, J. L. (2009). Observed reductions in school bullying, nonbullying aggression, and destructive bystander behavior: a longitudinal evaluation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 466–481. doi:10.1037/a0013839.

Fuligni, A., Tseng, V., & Lam, M. (1999). Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development, 70, 1030–1044. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00075.

Garcia-Reid, P., Reid, R. J., & Peterson, N. A. (2005). School engagement among Latino youth in an urban middle school context: valuing the role of social support. Education and Urban Society, 37, 257–275. doi:10.1177/0013124505275534.

Garringer, M., & MacRae, P. (2008). Building effective peer mentoring programs in schools: an introductory guide. Retrieved from http://www.edmentoring.org/.

Ginsburg-Block, M. D., Rohrbeck, C. A., & Fantuzzo, J. W. (2006). A meta-analytic review of social, self-concept and behavioural outcomes of peer-assisted learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 937–947. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.732.

Glew, G. M., Fan, M. Y., Katon, W., Rivara, F. P., & Kernic, M. A. (2005). Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 159, 1026–1031. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.11.1026.

Goebert, D. (2009). Social support, mental health, minorities, and acculturative stress. In S. Loue & M. Sajatovic (Eds.), Determinants of minority mental health and wellness (pp. 125–148). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-75659-2_7.

Grossman, J. B., & Tierney, J. P. (1998). Does mentoring work? An impact of the Big Brothers Big Sisters program. Evaluation Review, 22, 403–426. doi:10.1177/0193841X9802200304.

Grossman, D. C., Neckerman, H. J., Koepsell, T. D., Liu, P. Y., Asher, K. N., Beland, K., Frey, K., & Rivara, F. P. (1997). Effectiveness of a violence prevention curriculum among children in elementary school: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 277, 1605–1611. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540440039030.

Hahn, R., Fuqua-Whitley, D., Wethington, H., Lowy, J., Libeman, A . . . Dahlberg, L. (2007). The effectiveness of universal school-based programs for the prevention of violent and aggressive behavior: a report on recommendations of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 56, 1–12.

Horner, R., Sugai, G., Smolkowski, K., Eber, L., Nakasoto, J., Todd, A., & Esperanza, J. (2009). A randomized, wait-list controlled effectiveness trial assessing school-wide positive behavior support in elementary schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 11, 133–144. doi:10.1177/1098300709332067.

Hughes, J. N., Cavell, T. A., & Willson, V. (2001). Further evidence of the developmental significance of the teacher–student relationship. Journal of School Psychology, 39, 289–302. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(01)00074-7.

Hurley, J. C. (1997). The 4 × 4 block scheduling model: what do students have to say about it? National Association of Secondary School Principals Bulletin, 81, 53–64. doi:10.1177/019263659708159308.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1982). Effects of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning experiences on cross-ethnic interaction and friendships. Journal of Social Psychology, 118, 47–58. doi:10.1080/00224545.1982.9924417.

Jones, J. (2014). Best practices in providing culturally responsive interventions. In P. L. Harrison & A. Thomas (Eds.), Best practices in school psychology: foundations (pp. 49–60). Bethesda: National Association of School Psychologists.

Kamphaus, R. W., & Reynolds, C. R. (2007). Behavior assessment system for children—second edition (BASC-2): behavioral and emotional screening system (BESS). Bloomington: Pearson.

Karcher, M. (2005). The effect of developmental mentoring and high school mentors’ attendance on their younger mentees’ self‐esteem, social skills, and connectedness. Psychology in the Schools, 42, 65–77. doi:10.1002/pits.20025.

Karcher, M. (2007). Cross-age peer mentoring. Youth Mentoring: Research in Action, 1, 3–17.

Karcher, M. (2009). Increases in academic connectedness and self-esteem among high school students who serve as cross-age peer mentors. Professional School Counseling, 12, 292–299. doi:10.5330/PSC.n.2010-12.292.

Kendall, P. C., Safford, S., Flannery-Schroeder, E., & Webb, A. (2004). Child anxiety treatment: outcomes in adolescence and impact on substance use and depression at 7.4-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 276–287.

Khanna, M. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2008). Computer-assisted CBT for child anxiety: the coping cat CD-ROM. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 15, 159–165. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.02.002.

Khanna, M. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety: results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 737–745. doi:10.1037/a0019739.

Korinek, L., Walther-Thomas, C., McLaughlin, V. L., & Williams, B. T. (1999). Creating classroom communities and networks for student support. Intervention in School and Clinic, 35, 3–8.

Kortering, L. J., & Braziel, P. M. (2002). A look at high school programs as perceived by youth with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 25, 177–188.

Kusche, C. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (1994). The PATHS curriculum. Seattle: Developmental Research and Programs.

Ladd, G. W. (1990). Having friends, keeping friends, making friends, and being liked by peers in the classroom: predictors of children’s early school adjustment? Child Development, 61, 1081–1100. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02843.x.

LaGreca, A. M., & Lopez, N. (1998). Social anxiety among adolescents: linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 83–94. doi:10.1023/A:1022684520514.

Lane, K. L., Pierson, M. R., & Givner, C. C. (2003). Teacher expectations of student behavior: which skills do elementary and secondary teachers deem necessary for success in the classroom? Education and Treatment of Children, 26, 413–430.

Lazarus, P. J., Jimerson, S. R., & Brock, S. E. (2003). Helping children after natural disasters: information for caregivers and teachers. Bethesda: National Association of School Psychologists.

Limber, S. (2004). Implementation of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program in American schools: lessons learned from the field. In D. Espelage & S. Swearer (Eds.), Bullying in American schools: a social-ecological perspective on prevention and intervention (pp. 351–363). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Lochman, J. E., & Wells, K. C. (2002a). Contextual social-cognitive mediators and child outcome: a test of the theoretical model in the Coping Power Program. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 927–945. doi:10.1017/S0954579402004157.

Lochman, J. E., & Wells, K. C. (2002b). The Coping Power program at the middle-school transition: universal and indicated prevention effects. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 16, S40–S54. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.16.4S.S40.

Lochman, J. E., & Wells, K. C. (2003). Effectiveness study of Coping Power and classroom intervention with aggressive children: outcomes at a one-year follow-up. Behavior Therapy, 34, 493–515. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80032-1.

Lochman, J. E., Boxmeyer, C., Powell, N., Qu, L., Wells, K., & Windle, M. (2009). Dissemination of the Coping Power Program: importance of intensity of counselor training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 397–409. doi:10.1037/a0014514.

Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2002). Measuring perceived social support: development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASSS). Psychology in the Schools, 39, 1–18. doi:10.1002/pits.10004.

Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2003). What type of support do they need? Investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18, 231–252. doi:10.1521/scpq.18.3.231.22576.

Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2006). Social support as a buffer in the relationship between socioeconomic status and academic performance. School Psychology Quarterly, 21, 375–395. doi:10.1037/h0084129.

Masia, C. L., Klein, R. G., Storch, E. A., & Corda, B. (2001). School-based behavioral treatment for social anxiety disorder in adolescents: results of a pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 780–786. doi:10.1097/00004583-200107000-00012.

Masia-Warner, C., Klein, R. G., Dent, H. C., Fisher, P. H., Alvir, J., Albano, A. M . . . Guardino, M. (2005). School-based intervention for adolescents with social anxiety disorder: results of a controlled study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 707–722. doi:10.1007/s10802-005-7649-z.

Masia-Warner, C., Fisher, P. H., Shrout, P. E., Rathor, S., & Klein, R. G. (2007). Treating adolescents with social anxiety disorder in school: an attention control trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 676–686. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01737.x.

McMahon, S. D., & Washburn, J. J. (2003). Violence prevention: an evaluation of program effects with urban African American students. Journal of Primary Prevention, 24, 43–62. doi:10.1023/A:1025075617356.

McMahon, S. D., Washburn, J., Felix, E. D., Yakin, J., & Childrey, G. (2000). Violence prevention: program effects on urban preschool and kindergarten children. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 9, 271–281.

Metzler, C., Biglan, A., Rusby, J., & Sprague, J. (2001). Evaluation of a comprehensive behavior management program to improve school-wide positive behavior support. Education and Treatment of Children, 24, 448–479.

National Association of School Psychologists (2005). Position statement on home-school collaboration: establishing partnerships to enhance educational outcomes. Bethesda: Author.

Neil, A. L., & Christensen, H. (2009). Efficacy and effectiveness of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 208–215. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.002.

Nettles, S., Mucherah, W., & Jones, S. (2000). Understanding resilience: the role of social resources. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 5, 47–60. doi:10.1207/s15327671espr0501&2_4.

Nickerson, A. B., & Nagle, R. J. (2005). Parent and peer attachment in late childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25, 223–249. doi:10.1177/0272431604274174.

Olweus, D., & Limber, S. P. (2010). Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80, 120–129. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01015.x.

Olweus, D., Limber, S., & Mihalic, S. F. (1999). Blueprints for violence prevention. Book nine: bullying prevention program. Boulder: Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence.

Oyserman, D., & Lee, S. (2008). Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 311–342. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.311.

Reid, M. J., Webster-Stratton, C., & Hammond, M. (2003). Follow-up of children who received The Incredible Years intervention for oppositional-defiant disorder: maintenance and prediction of 2-year outcome. Behavior Therapy, 34, 471–491.

Reschly, A., & Christenson, S. (2012). Moving from “context matters” to engaged partnerships with families. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 22, 62–78. doi:10.1080/10474412.2011.649650.

Resnick, M. D., Harris, L. J., & Blum, R. W. (1993). The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 29, S1–S9. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb02257.x.

Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (2004). Behavior assessment system for children—second edition (BASC-2). Circle Pines: AGS.

Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (2009). Behavior assessment system for children—second edition (BASC-2): progress monitor. Circle Pines: AGS.

Reynolds, C. R., & Richmond, B. O. (2008). The revised children’s manifest anxiety scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Rigby, K. (2000). Effects of peer victimization in schools and perceived social support on adolescent well-being. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 57–68. doi:10.1006/jado.1999.0289.

Rosenfeld, L. B., Richman, J. M., & Bowen, G. L. (2000). Social support networks and school outcomes: the centrality of the teacher. Child Adolescent Social Work Journal, 17, 205–226. doi:10.1023/A:1007535930286.

Roseth, C. J., Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2008). Promoting early adolescents’ achievement and peer relationships: the effects of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic goal structures. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 223–246. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.223.

Rouse, C. E. (2005). Labor market consequences of an inadequate education. Paper prepared for the symposium on the Social Costs of Inadequate Education, Teachers College, Columbia University. New York, NY.

Rueger, S., Malecki, C., & Demaray, M. (2008). Gender differences in the relationship between perceived social support and student adjustment during early adolescence. School Psychology Quarterly, 23, 496–514. doi:10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.496.

Rueger, S., Malecki, C., & Demaray, M. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: comparisons across gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 47–61. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9368-6.

Saylor, C. F., & Leach, J. B. (2009). Perceived bullying and social support in students accessing special education inclusion programming. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 21, 69–80. doi:10.1007/s10882-008-9126-4.

Schaps, E., & Solomon, D. (1990). Schools and classrooms as caring communities. Educational Leadership, 48, 38–42.

Schwartz, D., Gorman, A. H., Nakamoto, J., & Toblin, R. L. (2005). Victimization in the peer group and children’s academic functioning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 425–435. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.97.3.425.

Sheridan, S. M., & Kratochwill, T. R. (2007). Conjoint behavioral consultation: promoting family-school connections and interventions. New York: Springer.

Sheridan, S., Eagle, J., Cowan, R., & Mickelson, W. (2001). The effects of conjoint behavioral consultation: results of a 4-year investigation. Journal of School Psychology, 39, 361–385. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(01)00079-6.

Shure, M. (2001). I can problem solve: an interpersonal cognitive problem-solving program. Champion: Research Press Co.

Slicker, E., & Palmer, D. (1993). Mentoring at-risk high school students: evaluation of a school-based program. School Counselor, 40, 327–334.

St. Pierre, T. L., Mark, M. M., Kaltreider, D. L., & Campbell, B. (2001). Boys and Girls Club and school collaborations: a longitudinal study of a multicomponent substance abuse prevention program for high-risk elementary school children. Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 87–106.

Stein, B. D., Jaycox, L. H., Kataoka, S. H., Wong, M., Wenli, T., Elliot, M. N., & Fink, A. (2003). A mental health intervention for school children exposed to violence: a randomized control trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 290, 603–611. doi:10.1001/jama.290.5.603.

Sugai, G., & Horner, R. (2006). A promising approach for expanding and sustaining school-wide positive behavior support. School Psychology Review, 35, 245–259.

Sulkowski, M. L., & Michael, K. (2014). Meeting the mental health needs of homeless students in schools: a multi-tiered system of support framework. Children and Youth Services Review, 44, 145–151. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.06.014.

Sulkowski, M. L., Wingfield, R. J., Jones, D., & Coulter, W. A. (2011). Response to intervention and interdisciplinary collaboration: joining hands to support children and families. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 27, 1–16. doi:10.1080/15377903.2011.565264.

Sulkowski, M. L., Demaray, M. K., Lazarus, P. J. (2012). Connecting students to schools to support their emotional well-being and academic success. Communiqué, 40, 1 & 20–22.

Sulkowski, M. L., Joyce, D. K., & Storch, E. A. (2012b). Treating childhood anxiety in schools: service delivery in a response to intervention paradigm. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 938–947. doi:10.1007/s10826-011-9553-1.

Sulkowski, M. L., Bauman, S., Dinner, S., Nixon, C., & Davis, S. (2014). An investigation into how students’ respond to being victimized by peer aggression. Journal of School Violence, 13, 339–358. doi:10.1080/15388220.2013.857344.

Tardy, C. H. (1985). Social support measurement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 13, 187–202. doi:10.1007/BF00905728.

Taub, J. (2002). Evaluation of the Second Step violence prevention program at a rural elementary school. School Psychology Review, 31, 186–200.

Taylor, G. (1997). Community building in schools: developing a “circle of friends”. Educational and Child Psychology, 14, 3.

Taylor, S. E., Sherman, D. K., Kim, H. S., Jarcho, J., Takagi, K., & Dunagan, M. S. (2004). Culture and social support: who seeks it and why. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 354–362. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.354.

Tremblay, R. E. (2000). The development of aggressive behavior during childhood: what have we learned in the past century? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24, 129–141. doi:10.1080/016502500383232.

Waasdorp, T., Bradshaw, C., & Leaf, P. (2012). The impact of schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports on bullying and peer rejection: a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 166, 149–156. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.755.

Wang, M., & Eccles, J. (2012). Social support matters: longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83, 877–895. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01745.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Hammond, M. (2004). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 105–124. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_11.

Williams, P., Barclay, L., & Schmied, V. (2004). Defining social support in context: a necessary step in improving research, intervention, and practice. Qualitative Health Research, 14, 942–960. doi:10.1177/1049732304266997.

Wodrich, D. L., Spencer, M. L., & Daley, K. B. (2006). Combining RTI and psychoeducational assessment: what we must assume to do otherwise. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 797–806. doi:10.1002/pits.20189.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Levels of Empirical Support

Appendix: Levels of Empirical Support

-

Well-established

-

The intervention is supported by well-designed empirical research (e.g., between-group design studies, random assignment to conditions, etc.). These studies indicate that outcomes for participants in the treatment group are better than outcomes for participants in a comparison condition or that treatment effects are comparable to those reported for existing empirically supported interventions. Moreover, the intervention is implemented with replicable protocols, and the majority of applicable studies suggest that it is beneficial to participants.

-

-

Promising

-

The intervention is supported by some well-designed research indicating that it results in particular, beneficial outcomes for participants. However, further research is needed to replicate these findings.

-

-

Emerging

-

Preliminary research findings indicate that the intervention is beneficial to participants. However, the nature of participant outcomes may be unclear, or there may be an absence of controlled research studies. Further studies with more rigorous research designs are needed to examine the efficacy and effectiveness of this treatment.

-

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grapin, S.L., Sulkowski, M.L. & Lazarus, P.J. A Multilevel Framework for Increasing Social Support in Schools. Contemp School Psychol 20, 93–106 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0051-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0051-0