Abstract

Introduction

Medical student specialty selection is complex and multifactorial. Pathology is often not selected as a primary career choice, despite its importance to patient care. Previous studies identified negative pathologist stereotypes and pathologist “invisibility” as potential reasons for this. Our objective was to better understand students’ perceptions of pathologists and how these contrast to the reality of practicing pathologists.

Methods

Medical students at Western University and Canadian pathologists participated in online surveys. Descriptive and mean comparisons were used to understand whether their perceptions were similar or different.

Results

Students found pathology interesting and clinically relevant. They felt that pathologists appeared more satisfied with their careers than other doctors, yet only one student intended to pursue a career in pathology. Although their estimation of pathologist workload was accurate, they did not understand what pathologists did on a daily basis and overestimated the time pathologists spent examining deceased persons.

Conclusion

Although medical students see the value and benefits of pathology, it is not an attractive career option, perhaps in part due to lack of understanding. To maintain adequate staffing in pathology departments, misconceptions need to be addressed and schools should consider actively seeking applicants who may be interested in a diagnostic specialty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anatomic pathology is a vital profession in the healthcare industry. Pathologists are critical in the diagnostic process, planning of patient care, quality assurance and patient safety; however, many medical students are reluctant to consider pathology as a viable career option. Inadequate staffing of pathology departments has been identified as a risk to patient safety [1], yet the Canadian Resident Matching Service data show that in the last 5 years (2012–2016), Anatomic Pathology has, on average, been the first ranked choice for just 0.7% of Canadian medical graduates [2] (in Canada, anatomic pathology and general pathology are separate specialties with separate residency programs). This compares to an average rate of 3.4% for diagnostic radiology, the other major diagnostic specialty. Over the same time period, there were an average of 13 (range 11–15) unfilled residency positions per year in pathology nationally after the first iteration of the match, and 3 per year (range 2–4) after the second iteration. Canada is not alone in this respect; recent data from the USA show declining numbers of US medical school graduates matching to pathology residency positions [3], and while there is some literature on why residents have/have not chosen pathology as a career path [4,5,6], this work has not translated into meaningful changes to medical school curricula, or to greater appeal of the profession for medical students.

The reasoning behind medical students’ specialty selection is not well understood. Some researchers have attempted to attribute specialty selection to personality types [7] while others have attributed specialty selection to controllable lifestyle [8]. It is likely that medical students choose a specialty for multifactorial reasons [9]; however, what remains consistent is that pathology is often not selected as a primary career choice even though it is a vital profession for healthcare.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the stereotype of an antisocial pathologist working alone in a mortuary is prevalent in our medical schools. Data to support this include recent Canadian studies involving medical students, residents and pathologists who all acknowledged this stereotype [5, 6]. In one of these studies [5], senior medical students interviewed at a major Canadian medical school described pathologists as “weirdos in bow-ties,” “geeky and boring,” “anti-social,” and “all about dead people.” It seems not unreasonable to suppose that these perceptions are common to medical students across North America, with potential negative effects on recruitment into pathology resident positions of students who feel that they do not fit these stereotypes and who do not want to work in a department full of anti-social weirdos. It is difficult to be certain when and how these misconceptions arise; whether students arrive at university with a preconceived idea of what a pathologist is like, based on family or media interactions, or whether, perhaps more likely, their opinion of pathologists is shaped during their preclinical and clinical years by their interactions with pathologists and other medical specialists.

This study takes a unique approach to studying perceptions about pathology as a career choice by contrasting students’ perceptions to those of practicing pathologists. Although designed for the Canadian context, identification of areas where there are similarities and differences might aid in determining how pathology can become more attractive to students, and potentially improve match rates in North America and beyond.

The objective of this study was to better understand the underlying conceptions, misconceptions and values of medical students, and how these contrast to the reality of current practicing pathologists. Five research questions guided our investigation:

-

1.

What informs students’ ideas surrounding pathology and pathologists? Are they based on personal experience or on the media portrayal?

-

2.

How do student perceptions of what pathologists do compare to what pathologists actually do?

-

3.

How do students rate the relevance of pathologists as part of a multidisciplinary patient care team and how does this compare to pathologists’ perceptions of their relevance?

-

4.

Do students enjoy pathology teaching at our institution and how does it compare to teaching in other specialties?

-

5.

What reasons might students use to choose a career in pathology and for what reasons did practicing pathologists choose their careers?

Methods

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Participants

Two groups of participants were recruited: medical students and pathologists. Medical students (n = 172) were recruited via e-mail using the mailing list of the Undergraduate Medical Education (UME) office at Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University. Pathologists (n = 828) were recruited using the mailing list of the Canadian Association of Pathologists - Association Canadienne des Pathologistes (CAP-ACP).

Survey Design

Two surveys were developed for this study:

-

1.

The student survey was designed to capture medical students’ perceptions of pathology as a career choice at the end of their second preclinical year. At our institution, the majority of pathology teaching takes the form of didactic large group and interactive small group teaching during years 1 and 2.

-

2.

The pathologist survey was designed to capture practicing pathologists’ observations and lived experiences in their own work life and self-perceptions of their role as part of the clinical team.

The surveys were developed for the Canadian context and drew on previous research and surveys looking at student perceptions of pathology [10].

In order to examine the contrasting points of view of students and pathologists, the surveys were very similar. First, participants answered a set of demographic questions on both surveys, followed by questions about student knowledge about pathology, perceived personality traits of pathologists, and pathologist self-identified personality traits. For clarity, broad definitions for “introvert” and “extravert” were provided with both surveys. Additionally, we asked questions about pathologist work life: type and location of work, typical work hours, on call commitments, and frequency of communication with others. We also developed two scales to compare students’ assumptions with pathologists’ actual experiences on two components we thought would be relevant to students’ lack of interest in pathology: (1) Communication: the extent to which pathologists communicate with others, and (2) Relevance and Value: how relevant and valued pathologists feel/are perceived as part of the healthcare team. The Communication construct attempted to capture the frequency in which pathologists communicate with others in the broader health network, including clinicians, staff, and other pathologists. This was based on 6-point scale that was frequency based: 1 = never, 2 = less than once per month, 3 = once per month, 4 = once per week, 5 = more than once per week, 6 = daily. The Relevance and Value construct consisted of statement-based items that participants responded to on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) and focused on the importance of pathologists as part of the multidisciplinary patient care team and the healthcare community, and their importance in clinical decision making and patient care.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were first used to outline the characteristics of the participants. Cronbach’s alpha was used to develop the Relevance and Value and the Communication scales (items associated with these scales are presented in Table 1). Independent t tests with 95% confidence intervals and Bonferroni corrections were used to evaluate the magnitude of differences between students’ and pathologists’ perceptions.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The response rate for medical students was 85% (145/172) and for pathologists was 19% (155/828). Mean age was 25 for students and 47 for pathologists, and there was a roughly equal gender distribution with slightly more males responding to both surveys (students: female 45%, male 55%; pathologists: female 46.75%, male 52.6%; other 0.65%).

Pathologist respondents were mostly practicing in academic centers (70%) with the remaining in community practice (22%), private laboratories (7%), and other settings (1%). Sixty-nine percent had medical students rotating through their department, and 59% were also involved in teaching medical students outside of scheduled departmental rotations. Forty-five percent had spent only 1 year practicing clinical medicine (typical in the Canadian context), 17% had spent < 1 year, and 10% had spent > 5 years in clinical medicine.

Eighty-three percent of students had decided on a probable career path with only one participant (0.6%) expecting to choose a career in pathology and another one considering pathology. The majority of students identified family medicine (25%) or surgery (20%) as their intended career path, with 17% answering “Don’t know.”

Perceived Personality Traits

Sixty percent of pathologists identified as introverts, with 21% identifying as extraverts and 18% as neither/both/unsure. Most comments made in response to this question indicated that pathologist respondents felt they had both introvert and extravert tendencies. Seventy-six percent of students felt that most of the pathologists they had met were introverts, 23.5% were unsure, and 0.5% felt that most of the pathologists they had met were extraverts.

Students’ Knowledge Base of Pathology

Ninety-seven percent of students stated that real life experiences informed their knowledge about what pathologists actually do (83% referencing pathology teaching in medical school and 14% referring to prior personal experience, such as an observership). Three percent cited TV shows or literary fiction as their main source of information about pathologists.

Medical students were more likely than pathologists to think that the entertainment industry’s portrayal of pathology is accurate (Fig. 1), t(295) = − 4.679, p < .001, d = 0.55. The majority of students (54%) disagreed with the statement “I have a good understanding of what a pathologist does on a daily basis.” Thirty-two percent agreed to some extent that they did understand a pathologist’s duties and the remainder (14%) were not sure.

Students’ Perceptions of What Pathologists Do Versus Lived Experience of Pathologists

Thirty-nine percent of pathologists claimed to work between 40 and 50 h per week, and 34% stated that they worked between 50 and 60 h per week. The average pathologist respondent is on call 4.71 days per month (SD = 5.54).

Students estimated pathologist work load correctly, with 68% believing a typical pathologist works a 40–50 h week. There was no significant difference between reported pathologist on call activities and students’ estimates of how often pathologists return to the hospital at night (t(261) = − 2.026, p > .01, d = 0.24), but they underestimated how often pathologists work on the weekend (t(200.7) = 4.112, p < .001, d = 0.51).

Seventy-eight percent of pathologists stated that they spend the majority of their time (75–100%) examining tissue from living patients; this was underestimated by students, with only 33% estimating that pathologists spend 75–100% of their time examining tissue from living patients, 32% estimating that pathologists spend 50–75% of their time examining tissue from living patients, and 12% estimating that pathologists split their time 50:50 between tissue from living patients and deceased patients.

Communication

Most pathologists indicated that they communicate (verbally or in person) on a daily basis with other pathologists (88%) and with technical/secretarial support staff (81%). Eighty-four percent communicate verbally or in person with clinician colleagues at least once per week, with 25% having daily communication. When it came to communication as a whole, medical students tended to think that pathologists communicated more often than they actually reported, t(284) = − 3.278, p < .01, d = 0.39; however, the communication scale had stronger internal consistency when completed by pathologists compared with students (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.50 for students and 0.64 for pathologists; moderate internal consistency [11]).

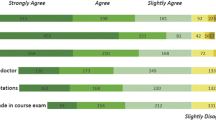

Relevance and Value

Most pathologists strongly agreed with the statements “Pathology is relevant to everyday clinical practice” (80%), “Pathology reports are important for clinical decision making” (84%), and “Pathologists play a key role in the multidisciplinary team” (80%). The majority of pathologists agreed or strongly agreed with the statements “Your clinical colleagues appreciate the value of your contribution to the multidisciplinary team” (65%) and “You have a voice at multidisciplinary team meetings” (68%). Students had similar perceptions; when we compared the Relevance and Value scales (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74 for students and 0.69 for pathologists), there were no differences between students (n = 139, m = 6.25, sd = 0.63) and pathologists (n = 145, m = 6.29, sd = 0.69). Thus, both perceive that pathologists are relevant and valuable in the healthcare system. Only 42% of pathologists agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “Pathologists are well respected amongst the medical and / or university community,” whereas 84% of students agreed or strongly agreed with this statement.

Pedagogical Aspects

We asked pathologists how many hours per week they spent in an educational role with one or more of the following groups: medical students, pathology residents, technicians, clinicians, and pathology colleagues. Forty-one percent spend between 1 and 4 h, 30% spend between 5 and 10 h, 15% spend < 1 h, and 14% spend > 10 h teaching per week.

Most students (67%) agreed that pathology is an interesting subject and 65% agreed that they enjoy pathology teaching. The majority (67%) felt that pathology teaching is as relevant to their future clinical practice as teaching in other specialties, but only 51% agreed that pathology teaching was as engaging as teaching in other specialties. Most students (75%) felt that the pathologists they had been exposed to were moderately satisfied (42%) or extremely satisfied (33%) with their teaching role.

A Career in Pathology

Pathologists were asked to select from a list, the top 3 reasons they chose a career in pathology and students were asked to select the top 3 reasons one might choose a career in pathology from the same list. The results are illustrated in Fig. 2. Interestingly, both groups selected the same top 3 reasons (intellectual challenge, interest in the field and good working hours) but in a different order. No individual in either group selected prestige as a reason to choose pathology as a career.

Sixty-four percent of pathologists were moderately or extremely satisfied with their career; 13%, however, were extremely dissatisfied. Most students did not recognize this level of dissatisfaction and actually rated pathologist career satisfaction higher than pathologists themselves did (Fig. 3), t(192.05) = − 4.885, p < .001, d = 0.56. Fifty-eight percent of students felt that career satisfaction was higher amongst pathologists than amongst other doctors.

Discussion

Our findings that 1 in 5 pathologists self-identify as extraverts and an additional 1 in 5 felt that they were either unsure or “a bit of both,” suggest that pathology is a specialty that may accommodate a diversity of personality types. As many medical students assess potential careers based on the type of people they would like to work with and where they see themselves “fitting in” [6, 12], it is important to convey the wide range of pathologist personalities to medical students and avoid the perpetuation of negative stereotypes and perceptions during medical school.

Most students correctly identified the typical working and on call hours of a Canadian pathologist. However, although able to estimate the workload correctly, when considering what pathologists actually do during these working hours, there was a student overestimation of time spent examining deceased patients and a majority of students disagreed with the statement “I have a good understanding of what a pathologist does on a daily basis.” This is despite an assertion by 97% of students that their knowledge about what pathologists do comes directly from real life experiences. The student perception that pathologists spend more time with deceased patients may be due to the following: (1) a skew towards autopsy pathology in their preclinical exposure to pathology (review of the teaching hours by pathologists in our undergraduate curriculum suggests that this is not the case), (2) the literary and televisual fictional portrayal of pathologists having had more influence than they realize, or (3) pathologists at our institution not doing a good enough job of conveying to students what they actually do. We suspect that the lack of understanding stems from a combination of factors 2 and 3. Autopsy pathology has the “wow factor” in pathology as it is the area that literary fiction and TV shows tend to focus on. If students are entering medical school with a preconception that pathologists spend their days doing autopsies, it is incumbent upon pathologists to actively contradict this belief in their teaching, rather than to assume that students will eventually realize what they do. Some institutions have chosen to offer elective opportunities for medical students to spend more time in their departments, allowing them to see firsthand how the laboratory works and what the day to day role of a pathologist entails, with reported success in student recruitment following these initiatives [13]. At our institution, we are designing a revised pathology curriculum for our preclinical medical students with early, clinically relevant pathology exposure. We try to put the pathologist’s role in the diagnostic pathway in a clinical context for our students and as part of Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) within the tasks of a physician. We have had positive feedback from our clinical clerks on pathology selectives which allow them to shadow pathologists and pathology residents during their surgical clerkship in order to learn about and experience a typical pathologist’s workday. As well, we have had positive feedback from medical students on interactive learning experiences such as frozen section role play and our cherry tomato fine needle aspiration biopsy sessions. Other opportunities for our students to learn about pathology include a pathology special interest group which is run by the medical students, and a 2-month summer research funded project which is awarded to one student each year and allows them to “live” in our residents’ room, availing of all departmental rounds and other learning activities while getting hands on research experience. Several students also interact with pathologist mentors via quality improvement and patient safety projects, research projects, and Patient-Centered Context: Integration & Application group learning which runs weekly throughout the preclinical curriculum.

An interesting finding in our data was the difference between how well pathologists feel they are respected amongst the medical and university community and how well students feel pathologists are respected, with 84% of students but only 42% of pathologists thinking that pathology is a well-respected profession. Despite this apparently high student perception of respect for pathologists, none selected prestige as a top 3 reason for choosing a career in pathology and one wonders if there was an element of response bias associated with this question, with students not wishing to appear disrespectful [14,15,16]. A majority of pathologists and students felt that pathologists were both relevant and valuable members of the healthcare team and pathologists felt that their clinical colleagues valued their contributions to the health care team, so it is unclear why there is a perception amongst pathologists that they are not respected. It may be that they feel individually respected in their own work environment, but feel that the profession as a whole is not respected. The reasons for this are not clear but may be in part due to awareness of pathology errors being highlighted in the media and a perception amongst some pathologists that they are under the public magnifying glass.

Somewhat surprisingly, a majority of students reported that they found pathology to be an interesting subject and that they enjoyed pathology teaching. They felt that it was as relevant to their future clinical practice as teaching in other specialties. This is in contradiction to the usual groans and/or laughter when informed that they are sitting down to 2 h of pathology teaching (anecdotal evidence!).

It is interesting that students rated career satisfaction higher for pathologists than for other doctors and higher than pathologists themselves rated their career satisfaction. This is due in part to student lack of knowledge or recognition of the 13% of Canadian pathologist respondents who are extremely dissatisfied with their careers. Of these pathologists, 75% worked in academic centers, reflecting the overall breakdown of respondents, and their survey responses in general reflected those of the other 87% of pathologists, with one minor difference; the top 3 reasons they chose a career in pathology were intellectual challenge, interest in the field and positive mentor/role model in pathology (compared to intellectual challenge, interest in the field and good working hours for the group as a whole). Whether these pathologists were dissatisfied with their careers because pathology as a profession was not the right choice for them or because of the institution/environment in which they are currently working, was not captured in our data. A potential limitation of our study is the low pathologist response rate (19%). It is not possible to determine 81% of pathologists did not reply because they are not involved/not interested in education, or if they are so busy educating that they did not have time to answer the survey! Regardless, we cannot ignore the possibility that our findings with respect to pathologist perceptions may have differed with a higher response rate. It is possible that surveys of Canadian physicians in different specialties may yield similar results with regard to the percentage of dissatisfaction, given that North American residents have to make specialty decisions early, without getting to try out different specialties beyond clerkship. In a study from the USA, pathologists self-reported below average burnout rates compared to other physicians and above average satisfaction with work-life balance [17].

Conclusion

Several studies have examined reasons why medical graduates did not select a career in pathology [4,5,6]. We have taken a novel approach and compared the perceptions of medical students with data obtained from practicing pathologists to try to understand where there are similarities and differences which may inform career choice. Although previous studies have cited that pathology and/or pathologists are “invisible” in medical school [5, 6] and that pathology is thought to be too boring, repetitive and academic [4, 5], we have presented contrasting data. Medical students at our institution reported finding pathology both interesting and clinically relevant. They see pathologists as valuable members of the health care team and also think that pathologists have a higher level of career satisfaction than other doctors. This highlights the complexity of career choice for medical students. Why do they pursue careers which appear to them to be less satisfying rather than those which appear satisfying, interesting and important for patient care? We would argue that the simple answer is that the majority of students enter medical school with the intention of directly treating patients and pathology does not offer that opportunity for the most part. This raises the question of whether medical school admissions teams should consider actively seeking out applicants who are interested in the “diagnostic specialties” to ensure an adequate workforce in the future.

For those whom direct patient contact is a must, pathology is clearly not an option they will consider, and it is not our goal to attempt to recruit large numbers of students to a specialty with limited regional residency positions; however, there may be students who are simply misinformed about pathology, who are not willing to consider a career which they think will involve daily autopsies but who would thrive in a typical pathology environment. Early and meaningful exposure to pathologists may empower these students to make better informed career choices and may improve patient safety in the longer term. Future studies should consider the perceptions of students in their clerkship years as these may differ as students gain more clinical experience. Through improved understanding of medical trainees’ perceptions, programs can better design methods to highlight the social and personal benefits of pathology as a career choice.

References

Sir –, Osler W. The Report with Recommendations of a Commission of Inquiry into Pathology Services at the Miramichi Regional Health Authority. [cited 2017 Nov 23];1849–919. Available from: http://www.gnb.ca/0051/index-e.asp.

R-1 match reports - CaRMS [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.carms.ca/en/data-and-reports/r-1/.

Jajosky RP, Jajosky AN, Kleven DT, Singh G. Fewer seniors from United States allopathic medical schools are filling pathology residency positions in the main residency match, 2008-2017. Hum Pathol. 2018;73:26-32.

Ford JC. If not, why not? Reasons why Canadian postgraduate trainees chose-or did not choose-to become pathologists. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:566–73. [Internet]. Elsevier Inc. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2009.09.012.

Hung T, Jarvis-Selinger S, Ford JC. Residency choices by graduating medical students: Why not pathology? Hum Pathol. 2011;42:802–7. [Internet]. Elsevier Inc. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2010.10.018.

Raphael S, Lingard L. Choosing pathology: a qualitative analysis of the changing factors affecting medical career choice | International Association of Medical Science Educators - IAMSE. Med Sci Educ [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2017 Nov 23];15. Available from: http://www.iamse.org/mse-article/choosing-pathology-a-qualitative-analysis-of-the-changing-factors-affecting-medical-career-choice/.

Borges NJ, Savickas ML. Personality and medical specialty choice: a literature review and integration. J Career Assess. 2002;10:362–80. [cited 2017 Nov 23] Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/10672702010003006.

Dorsey RE, Jarjoura D, Rutecki GW. The influence of controllable lifestyle and sex on the specialty choices of graduating U.S. medical students, 1996-2003. Acad Med. 2005;80:791–6.

Freed GL, Stockman JA. Oversimplifying primary care supply and shortages. JAMA. 2009;301:1920–2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.619.

Holland L, Bosch B. Medical students’ perceptions of pathology and the effect of the second-year pathology course. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1–8.

Hinton PR, McMurray I, Brownlow C. SPSS explained. Hove: Routledge; 2004.

Hill EJR, Bowman KA, Stalmeijer RE, Solomon Y, Dornan T. Can I cut it? Medical students’ perceptions of surgeons and surgical careers. Am J Surg. 2014;208:860–7.

Van Es MB Grad Dip Med SL, Fpa C, Grassi MBBS T, Velan MBBS GM, Kumar MB RK, Pryor WM. Inspiring medical students to love pathology. Hum Pathol. 2015;46:1408. Available from: https://journals-scholarsportal-info.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/pdf/00468177/v46i0009/1408_imstlp.xml. Accessed 7 June 2018.

DeMaio TJ. Social desirability and survey measurment: a review. In: Turner CF, Martin E, editors. Surv Subj Phenomena, Vol 2. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1984 [cited 2018 Jan 18]. p. 257–82. Available from: https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=cQi5BgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA257&dq=Social+desirability+and+survey+measurement:+A+review&ots=HUwJhaxPrF&sig=Z1xY8I5dD-1owm5VMNG62ltVxM8&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Socialdesirabilityandsurveymeasurement%3A.

Randall DM, Fernandes MF. The social desirability response bias in ethics research. J Bus Ethics. 1991;10:805–17. Kluwer Academic Publishers [cited 2018 Jan 18] Available from: http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/10.1007/BF00383696.

Krumpal I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: a literature review. Qual Quant. 2013;47:2025–47. Springer Netherlands. [cited 2018 Jan 18]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9.

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:–1377. American Medical Association; [cited 2018 Jun 7] Available from: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Barbara Bosch, Wayne State University, for providing access to her original survey.

Funding

This project was funded by a grant from PIFAD (Western University Pathology Internal Funds for Academic Development), Project # R5511A01, was approved by Western University Research Ethics Board and was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walsh, J.C., Padgett, J., Weir, M.M. et al. Comparing Perceptions of Pathology as a Medical Specialty Between Canadian Pathologists and Pre-Clinical Medical Students. Med.Sci.Educ. 28, 625–632 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-018-0596-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-018-0596-4