Abstract

Residents’ career choices and professional motivation can be affected from perception of their role and recognition within a medical team as well as their educational and workplace experiences. To evaluate pathology trainees’ perceptions of their pathology residency, we conducted a 42-item survey via a web-based link questioning respondents’ personal and institutional background, workplace, training conditions, and job satisfaction level. For the 208 residents from different European countries who responded, personal expectations in terms of quality of life (53%) and scientific excitement (52%) were the most common reasons why they chose and enjoy pathology. Sixty-six percent were satisfied about their relationship with other people working in their department, although excessive time spent on gross examination appeared less satisfactory. A set residency training program (core curriculum), a set annual scientific curriculum, and a residency program director existed in the program of 58, 60, and 69% respondents, respectively. Most respondents (76%) considered that pathologists have a direct and high impact on patient management, but only 32% agreed that pathologists cooperate with clinicians/surgeons adequately. Most (95%) found that patients barely know what pathologists do. Only 22% considered pathology and pathologists to be adequately positioned in their country’s health care system. Almost 84% were happy to have chosen pathology, describing it as “puzzle solving,” “a different fascinating world,” and “challenging while being crucial for patient management.” More than two thirds (72%) considered pathology and pathologists to face a bright future. However, a noticeable number of respondents commented on the need for better physical working conditions, a better organized training program, more interaction with experienced pathologists, and deeper knowledge on molecular pathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multiple factors affect career choice, including individual personality, skills, and expectations. Sociological characteristics such as bioscientific and biosocial orientation, academic interest, prestige, and income expectation have been correlated with medical students’ career choices [1]. Pathology seems to be a less popular residency choice among medical students in several countries [2,3,4]. It has been suggested that medical students simply do not consider pathology as a career choice, mainly because they think pathology is invisible in clinical practice and are insufficiently aware of what pathologists do [5]. Although the role and recognition of pathologists within a medical team vary from one country to another and/or between medical specialties, our personal observations also suggest that, despite its crucial effect on patient management, underestimation of the importance of pathology by both clinicians and patients may also affect whether or not young medical graduates will consider pathology as a career choice.

Once the residency period is started, several factors such as workplace conditions, training modalities, and psychosocial conditions may affect personal experiences and job satisfaction. Previous studies mostly focused on pathology training [6,7,8,9,10] or overall job satisfaction level of residents or specialists [11, 12] (as part of large studies including also other disciplines) and provided limited data about how the pathology residency period is perceived. Only one report focused on how pathologists see their clinical role [13]. However, to our knowledge, there are no studies probing into pathology residents’ perceptions of pathology.

Since residency represents a period that all pathologists go through, resident’s opinions are valuable to improve teaching and learning skills and daily practice. Therefore, we conducted a multinational survey to have resident comments on working and training conditions, perceptions of pathology, and job satisfaction. The results provide thorough insight in how residents perceive pathology residency.

Material and methods

Survey design and data collection

We conducted a cross-sectional 42-item survey questioning respondents’ (1) personal demographics and institutional background, (2) workplace physical conditions, (3) institutional training program, (4) professional recognition in the team (hierarchical order in the department), (5) awareness of pathology, (6) perception of pathology, and (7) level of happiness and job satisfaction. The survey was delivered via a web-based link, e-mail, and personally. Questions were designated based on observations and self-experience of the authors as well as previous job satisfaction surveys [12, 14]. Different question types as Likert scaling, yes/no questions, open-ended, close-ended, and partial open-ended questions were used to evaluate different aspects. Demographic and institutional characteristics were mainly questioned using yes/no questions and close-ended questions. A 5-point score was used for Likert-type questions: 1: Strongly disagree, 2: Somewhat disagree, 3: Neutral, 4: Somewhat agree, and 5: Strongly agree. For Likert-type questions on respondents’ perception of pathology, a few statements that non-pathology residents used about pathology and previously reported by Ford [2] were also used.

Data analysis

For Likert-type questions about physical conditions, hierarchical order, training conditions, and perception of pathology, mean scores were calculated on individual respondents’ answers. Based on the crude overall mean score throughout all items in the questionnaire, a cutoff level of 3.5 points was determined as mean dimension scores, based on previous studies [15]. The outcome variables were converted into dichotomous variables for statistical purposes. Respondents’ awareness and happiness levels were also evaluated using Likert-type questions and the respondents’ answer scores (between 1 and 5 points) were directly correlated with other variables. Partial/complete open-ended questions were mainly used in the last section (perception and job satisfaction) and similar answers were included in the same category for homogeneity. For statistical purposes, the countries of the respondents were categorized according to World Bank income classification [16].

Statistical analysis

The relation of each dimension’s dichotomous variables with the independent variables was determined with χ 2 tests. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare two groups, while Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare ≥3 groups. The variables correlating with the dependent variables in these hypothesis tests were included in logistic regression analysis. Youngest age group (25–27), females, middle-income countries, number of residents (1–10 persons), working hours (≥8 h/day), and hours spent on gross examination (≥15 h/week) were the reference categories. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Analyses were made separately for physical conditions, hierarchy, training conditions, awareness, and happiness dimensions. For each dimension, only the variables found statistically significant in bivariate analyses were included in multivariate analysis. The independent effect of each variable was checked in the first step (crude) and then controlled for all variables in the equation (adjusted). A value of p < 0.05 (two-sided) was considered statistically significant. For the Spearman correlation analysis, r = 0.75 − 1 was considered as a very strong positive correlation (0 = no linear relationship, 0–0.24 = a weak positive correlation, 0.25–0.49 = a moderate positive correlation, and 0.50–0.74 = a strong positive correlation). Statistical analysis was performed using the software SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL).

Results

Personal background

The survey was completed by 222 respondents from 25 countries. Answers from non-European respondents (10 respondents from the USA, 1 from Canada, 1 from Argentina, 1 from Algeria, and 1 from Mozambique) were excluded from statistical analysis, considering that their residency training program differs significantly from other respondents’ countries and/or that they would not constitute a representative sample of their residency program.

Response rate (calculated by the ratio of the number of respondents to total number of residents working at their institutions) was low (17.6%). According to World Bank classification, 41.8% of the respondents lived in a high-income country [Netherlands (n = 29), Portugal (n = 14), Belgium (n = 6), Croatia (n = 7), Czech Republic (n = 4), Denmark (n = 2), France (n = 5), Italy (n = 3), Slovenia (n = 4), Sweden (n = 6), UK (n = 3), Greece, Poland, Spain, and Switzerland (n = 1 for each)], while 58.2% lived in a middle-income country [Turkey (n = 105), Ukraine (n = 7), Macedonia (n = 6), Serbia (n = 2), Romania (n = 1)]. A majority of the respondents was female (73.1%), with a female predominance in middle-income countries (p = 0.001). Median age was 29 ± 3.61 years old (range 25–42 years old) (Table 1) and residents from middle-income countries tended to be younger (p < 0.001).

Institutional background

Institutional background data are shown in Table 1. No statistically significant difference was found between high-income and middle-income countries regarding daily work hours, total number of biopsies, and total number of teaching staff. However, the number of residents was higher in high-income countries (p = 0.017) and the number of weekly grossing hours was higher in middle-income countries (p < 0.01).

Workplace conditions

Workplace conditions are summarized in Fig. 1. Physical conditions were better in university hospitals with a higher mean score for university hospitals than other hospitals (3.38 vs. 2.86, p = 0.012). A significant statistical association was found between physical conditions’ mean score and World Bank income levels (i.e., better conditions in high-income countries) (p < 0.001; mean scores were 3.85 ± 0.87 vs. 2.85 ± 1.01 for high-income and middle income countries, respectively). Physical conditions’ mean score was also significantly higher for respondents that worked with ≥11 residents (p = 0.004; 3.61 ± 1.04 vs. 3.13 ± 1.05). No statistically significant difference was found between physical conditions’ mean score and other variables.

Professional recognition and relationship with other people working in the department were evaluated under the heading hierarchical order. Although 66% were satisfied about overall hierarchy regardless of age, gender, and seniority, a significant association was observed between hierarchical order mean score and income levels (p < 0.001; mean scores were 3.56 ± 0.64 vs. 3.24 ± 0.43 for high-income and middle-income countries, respectively). A lower number of weekly grossing hours was associated with better relationships (p = 0,022; mean scores were 3.48 ± 0.55, 3.32 ± 0.6, and 3.24 ± 0.5 for 0–8, 9–14, and >15 h, respectively).

Interestingly, almost half (40.3%) experienced verbal abuse during their residency period and of 84 respondents who experienced verbal abuse, 69% were abused by teaching staff, 22.6% by supervisor, and 14% by their colleagues.

Daily practice responsibilities were grouped as gross examination, microscopic examination, autopsy, attending multidisciplinary councils/scientific meetings, recruiting patient data, assistance in student affairs, and secretarial work in the sign-out process. The respondents stated that the most disturbing issues in their daily routine were secretarial matters (writing or editing sign-out reports, taking manual notes in the grossing room when a voice recording system or assisting staff were not available; 65.9% for all respondents and particularly in university hospitals, p = 0.002) and recruiting additional patient data (45.2%, particularly in middle-income countries, p < 0.001), while attending and participating in scientific meetings and microscopic examination were considered as disturbing daily responsibilities by only 9.1 and 14.4%, respectively. Gross examination appeared to be a disturbing factor particularly in non-university hospitals (p = 0.045). Almost one third (29.8%) of the respondents were disturbed by student affairs, especially in university hospitals (p < 0.001) and in middle-income countries (p = 0.03). The number of the respondents disturbed by student affairs and secretarial matters was higher with a higher number of teaching staff at the institution (p < 0.05, chi-square).

Training conditions

Training conditions were better in university hospitals (mean scores 3.50 ± 0.78 vs. 3.21 ± 0.70 for university and non-university hospitals). A set training program (core curriculum), a set annual scientific curriculum, and a residency program director existed for 58.2, 60.1, and 69.2% respondents, respectively. The number of the residents was significantly higher in institutions with a program director (p < 0.002). Presence of a core curriculum and annual scientific curriculum was associated with income level of the countries (p < 0.01, chi-square) and the number of teaching staff (p < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U). However, only 46% found that their annual scientific program was sufficient and 41% considered that scientific activity prepared by residents was insufficient, which was not related to country income level. More than half of the respondents found that they were trained adequately on gross and microscopic examination (51 and 61.5%, respectively) but only 43% found theoretical training sufficient (Fig. 1). Although there was no statistically significant difference between high-income and middle-income countries regarding gross and/or theoretical training, microscopic training scores were higher in high-income countries (p = 0.002; mean scores 3.82 ± 1.15 vs. 3.38 ± 1.12).

Seventy-six percent declared they had access to scientific resources (textbooks, recent articles, and publications) but only 53% of the respondents reported that they were being encouraged to participate in scientific research. Accessibility to scientific resources and encouragement to conduct scientific research were significantly higher in high-income countries (p = 0.008 and p = 0.016, respectively). Only 44% reported that they had adequate support/supervision while preparing presentations, regardless of the country they lived in.

Perception of pathology and job satisfaction

Most respondents (76%) agreed that pathologists have a direct and high impact on patient management, more so in high-income countries (91 vs. 66%). However, 95% considered that patients barely know about pathologists and 82% considered that other clinicians do not know what pathologists do, without any association with the resident country.

Only one third (32%) of the respondents found that pathologists cooperate adequately with clinicians and surgeons. Moreover, 78% considered that pathology and pathologists are adequately recognized in their country, as there was an adverse correlation with country income levels (p < 0.001; 1.93 ± 0.95 vs. 3.12 ± 1.23 for middle-income vs. high-income countries).

Prior to choosing a pathology residency, 64% were aware of what pathologists do in daily practice, microscopic examination being the best known part (96.6%) and considered as the most interesting part of pathology by 76%, while autopsy was unknown by 31.7%. Level of awareness tended to be higher in high-income countries (p < 0.001; 4.17 ± 1.00 vs. 3.31 ± 1.20). No significant correlation was found between awareness and perception.

Almost 84% were happy to have chosen pathology as a profession, which was significantly associated with country income levels (p < 0.001; 4.62 ± 0.65 vs. 3.94 ± 0.90). Almost 45% were dissatisfied by their remuneration (29% neutral and 26% satisfied) and only 41.3% reported that as a pathologist, their remuneration would be satisfactory. However, 77% found that they could achieve their career goals as a pathologist.

No significant correlation was found between perception and happiness. However, a positive significant correlation was observed between happiness and hierarchical order (i.e., professional recognition and relationship with other people working in the department) and between happiness and awareness (p < 0.001; Spearman’s rho, 0.302 and 0.297, respectively). Hierarchical order mean score also showed a significant positive correlation with physical conditions, training satisfaction, and awareness scores (p < 0.001; Spearman’s rho, 0.467, 0.499, and 0.252). Training satisfaction mean score was also correlated with physical conditions’ mean score (r = 0.402 and p < 0.001) and happiness scores (r = 0.178 and p = 0.010).

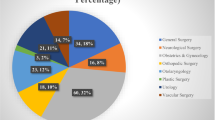

Quality of life and personal expectations (52.9%) and scientific excitement (51.7%) were the most frequent reasons why respondents chose and enjoy pathology (Table 2). Even though 72% considered the future to be bright, almost half (46%) would like to have better physical conditions in the pathology laboratory and a noticeable proportion (20%) commented on the need for a more organized training program, better integration of pathology into surgery practice (13%), need for more interaction with senior pathologists (6.2%), better visibility of pathology to patients and other medical specialties (4.3%), and higher level of knowledge on molecular pathology (2.4%).

Logistic regression analysis

Results of the logistic regression analyses are given in Table 3. Physical conditions were better in high-income countries and in institutions with more than 10 residents. After adjustment (Model 2), these two variables remained statistically significant (OR = 4.19 (95% CI = 2.15–8.15), p < 0.001 and OR = 2.97 (95% CI = 1.47–6.02), p < 0.05). Hierarchical order mean score was also found to be associated with country income level and number of the residents in both Models 1 and 2 (before and after the adjustment) with OR = 2.39 (95% CI = 1.29–4.42), p < 0.05 and OR = 2.16 (95% CI = 1.11–4.20), p < 0.05), respectively. Training conditions’ satisfaction mean score was significantly higher for institutions with more than 10 residents with OR = 2.83 (95% CI = 1.48–5.39), p < 0.05. Awareness and happiness scores were higher in high-income countries (OR = 3.07 (95% CI = 1.62–5.81) and OR = 4.06 (95% CI = 1.60–10.31), p < 0.05). Lower perception mean scores were observed for respondents working more than 8 h/day (OR = 0.36; 95% CI = 0.18–0.75). No significant association between high-income and middle-income countries was found regarding training conditions’ satisfaction and perception mean scores.

Discussion

Pathologists are indispensable members of the medical team and their professional activity directly affects treatment and survival of patients, although they are generally “invisible” to patients and clinicians. Their perspective on life in general and professional life in particular might differ from that of other medical professionals. Residents’ experiences and job satisfaction levels are valuable to maintain continued and updated residency programs, which is important to keep this perspective dynamic and positive. It stands to reason that several internal (personal) and external factors affect individual experiences and perception of satisfaction, some of which are shared by others, regardless of age, gender, or ethnicity.

Our results suggest that perceptions of physical and workplace conditions (including hierarchical order) differ mainly by country income level. In the context of pathology practice, economically strong countries have larger laboratories with better physical conditions, along with more residents or more staff and also a higher level of professional recognition. A substantial number of respondents complained about having to do secretarial work such as typing sign-out reports, taking manual notes in the grossing room, or recruiting additional patient data (i.e., radiology reports, previous pathology reports, or clinical notes from other hospitals), which implies lack of adequate secretarial staff or software for documentation, resulting in using residents as an extra pair of hands.

Educational experiences are heterogeneous, considering that almost every country has its own medical education system with different provisions and problems. Post et al. recently reported that employers not only expect well-developed diagnostic skills from newly trained pathologists but also require strong work ethics and outstanding professionalism [17]. Postgraduate education, including in pathology, is an interactive process, and problems that interfere with pathology resident training may originate both from trainer and trainee. Our results show that training conditions are better in university hospitals, that the presence of a set residency training program (core curriculum) and a set annual scientific curriculum was associated with country income levels and the number of teaching staff. This suggests that larger institutions with a numerically larger teaching staff have more organized and standardized teaching activities. However, this goes along with more active participation of residents in undergraduate medical education (i.e., participating in microscopy training sessions), which was found to be disturbing by 29.8%. However, several reports suggest that such activities improve residents’ teaching and communication skills. Talmon et al. found an association between the amount of pathology residents’ teaching activity and their mean performance on in-service examinations [18]. Also, Weiss and Needlman found that formal teaching enhances knowledge acquisition relative to self-study and lecture attendance among residents in pediatrics [19].

There was a core curriculum, a set annual scientific curriculum, and a residency program director for 58, 60, and 69% of the respondents, respectively. Unfortunately, more than half (54%) of the respondents evaluated their annual scientific program as insufficient and 41% considered that scientific activity (case presentation, article writing, and seminar hours) conducted by residents was insufficient. Moreover, more than half (56%) found that support/supervision while preparing their presentations was inadequate, regardless of the country they lived in. This is of some concern because pathologists are considered as the “doctor’s doctor,” in continuing to educate pathologists and colleagues of other medical specialties [20]. Inadequate support for and supervision of young trainees in preparing scientific communications might not only affect today’s residents but also impact on the quality of teaching of future medical students, residents, and medical specialists.

We found no statistically significant differences between high-income and middle-income countries regarding training in gross examination or basic knowledge education. However, in high-income countries, higher satisfaction scores of training in microscopy were noted. In a previous study [21], the daily diagnostic workload was proposed as a limiting major factor for optimal learning during pathology training. Our results indicate that in high-income countries, a given workload is performed by a larger number of pathology residents than in middle-income countries. It is likely that this higher workload and the accompanying need to complete several missions in a given time period interferes with optimal training.

Overall, hierarchical relationships were found satisfactory by 66% of the respondents, regardless of age, gender, and resident’s seniority. Of note, a lower number of weekly hours of gross examination was associated with better relationships, which suggests that time spent on grossing interferes with inter-collegial relationships. Furthermore, a noticeable number (40%) of respondents from different countries and types of institutions reported verbal abuse, in particular by teaching staff. This needs to be interpreted cautiously, as there are several types of mistreatment in professional life [22] and intercultural differences exist in terms of definition of verbal abuse and sensitivity to it [23]. Our survey is insufficiently detailed to comment on this but the finding as such merits to be further investigated, as it will affect job satisfaction in particular during the residency period. Open transparent feedback between residents, teaching staff, and program director may prevent such events and prevent trainee discouragement.

One of the main reasons for this study was to document residents’ perception of pathology. Most respondents (76%) found that pathologists have a direct and high impact on patient management, but significantly less (32%) found that cooperation with clinicians and surgeons is adequate while only few (5%) found that pathologists are visible to the public. This is consistent with previous statements which go as far as stating that pathologists and clinicians are perceived as coming from different planets [24, 25]. As in many countries undergraduate medical education mainly focuses on clinical practice and patient care, it is not surprising that in such a setting, clinicians and certainly patients hardly know what pathologists do, even though their activity is of crucial importance for patient management. Moreover, only 22% of the respondents considered that pathology and pathologists are adequately positioned in their country’s health care system, which we translate into 78% having some concerns regarding this issue. This concern was shared by respondents from different countries and types of institutions and should be taken as a warning signal to take necessary steps to improve or consolidate the position of pathology and pathologists.

On the upside, more than one quarter of the respondents considered pathology as a “different fascinating world” allowing them to unveil scientific or medical enigmas. This result is quite comparable with the findings of a study conducted by Ford among Canadian pathology residents [2], in which answers to the open-ended questions were quite similar to those in our study. Of 208 respondents, 32% chose/enjoyed pathology because they consider pathology to provide a better quality of life due to relatively flexible work hours and to be less stressful without direct patient contact despite major importance for patient management. In 1989, Schwartz et al. reported that “controllable lifestyle” was becoming an increasingly important factor in choosing a specialty by fresh medical graduates, and pathology was among the favored specialties [26]. This tendency apparently has not changed in the subsequent 30 years. It is also noteworthy that only two respondents stated to have chosen pathology while in medical school. Holland et al. explored the perceptions of medical students regarding pathology and the effect of the sophomore (i.e., second year in medical school) pathology course and observed that a second year pathology course had little effect on medical students’ perceptions but did provide some increase in their understanding of pathology as a profession [27]. The authors suggested that initial introduction about pathology practice in the second year and providing more insight about diagnostic processes in pathology in clinical years is necessary to combat some misconceptions. We obtained favorable feedback in student queries at our institutions (Ege University) following introduction of pathology sessions into the years of clinical clerkships, while basic pathology education was concentrated in the early years of the curriculum (unpublished data). Brooks et al. reported that a 10-week pathology fellowship during the summer following the first (preclinical) year of medical school was equally effective in attracting medical students into pathology residency than a fellowship after the second year, in which the basic pathology course was taught [28]. Likewise, Van Es et al. reported on an 8-week elective course for final year medical students and suggest that focused exposure of medical students to pathology has a positive impact on the choice of pathology as a career [29].

Our results indicate that most respondents were happy to have chosen pathology as a profession and perceived their future as bright. Interestingly, 77% of the respondents were convinced that they would attain their career goal in pathology while only 41% expected to be financially satisfied, which suggests that financial incentives are not the leading motive for those choosing pathology as a career.

For almost half of the respondents, physical conditions in their pathology department were unsatisfactory and a noticeable proportion found that the training program needed to be better organized, needed more focus on molecular pathology training, and needed more interaction with senior pathologists. The recent report by Ziai and Smith goes in the same direction in suggesting that pathology training should accommodate new practice models and technologies, including genomics, informatics, digital pathology, predictive pathology, and in vivo microscopy [30]. Accreditation and quality assurance requirements may be a good way to assess efficacy of pathology training programs [31, 32].

An important limitation of our study is the country distribution of the respondents. Non-European respondents were excluded from statistical analysis due to unrepresentative numbers and differences in the residency programs. Moreover, although our respondents came from 25 different countries, the most populated European countries [33] were not properly represented. A dominant number of respondents were from a single country (i.e., Turkey), which is the reason why we decided to dichotomize the groups of respondents into coming from high-income and middle-income countries rather than considering the response by country.

In spite of these shortcomings, we are convinced that the study provides important insight into residency experiences in different parts of Europe. Shared comments on insufficient support for and supervision of residents notably in regard of scientific activities, the need of attention for teaching skills, and more emphasis on standardizing training programs globally emerge as points program directors need to pay attention to. Particularly encouraging findings are that positive resident perception of pathology is quite similar across European countries, as they are “happy to have chosen pathology,” define it as “puzzle solving,” and find it “exciting” and “crucial for patient management.” The responses also suggest that the “invisible” nature of pathology and of pathologists for patients and even for clinicians should motivate pathologists to dedicate more effort to clarify why their specialty is so important.

This first survey of pathology residents’ perspective on pathology and on their residency provides useful insight into factors associated with resident satisfaction and identifies some major shortcomings in pathology training.

References

Murdoch MM, Kressin N, Fortier L et al (2001) Evaluating the psychometric properties of a scale to measure medical students’ career-related values. Acad Med 76:157–165

Ford JC (2010) If not, why not? Reasons why Canadian postgraduate trainees chose—or did not choose—to become pathologists. Hum Pathol 41(4):566–573. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2009.09.012

Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Turner G et al (2006) Career choices for pathology: national surveys of graduates of 1974-2002 from UK medical schools. J Pathol 208:446–452

Brooks EG, Paus AM, Corliss RF, Ranheim EA (2016) Enhancing preclinical year pathology exposure: the Angevine approach. Hum Pathol 53:58–62. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2016.02.006

Hung T, Jarvis-Selinger S, Ford JC (2010) Residency choices by graduating medical students: why not pathology? Hum Pathol 42(6):802–807. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2010.10.018

Alexander CB (2011) Pathology graduate medical education (overview from 2006-2010). Hum Pathol 42(6):763–769. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2010.11.008

Domen RE, Baccon J (2014) Pathology residency training: time for a new paradigm. Hum Pathol 45(6):1125–1129. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2014.02.026

Hsieh CM, Nolan NJ (2015) Confidence, knowledge, and skills at the beginning of residency. A survey of pathology residents. Am J Clin Pathol 143(1):11–17. doi:10.1309/AJCP3TAFU7NYRIQF

Grzybicki DM, Vrbin CM (2003) Pathology resident attitudes and opinions about pathologists’ assistants. Arch Pathol Lab Med 127(6):666–672

Rinsler MG (1977) Training of pathologists in countries belonging to the European Economic Community. J Clin Pathol 30(9):788–799

Martins MJ, Laíns I, Brochado B et al (2011) Career satisfaction of medical residents in Portugal. Acta Medica Port 28(2):209–221

González-Martínez JF, García-García JA, Del Rosario A-VM et al (2011) Assessment of medical residents’ satisfaction. Cir Cir 79(2):156–167

Jenkins D, Philips Z, Grisaffiî K, Whynes DK (2002) The boundaries of cellular pathology: how pathologists see their clinical role. J Pathol 196(3):356–363

Yeo H, Viola K, Berg D et al (2009) Attitudes, training experiences, and professional expectations of US general surgery residents: a national survey. JAMA 302(12):1301–1308. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1386

Martha C, Griffet J (2007) Brief report: how do adolescents perceive the risks related to cell-phone use? J Adolesc 30:513–521

https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (Access date: 15.03.2017)

Post MD, Johnson K, Brissette MD et al (2015) Expectations for newly trained pathologists: report of a survey from the Graduate Medical Education Committee of the College of American Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.5858/arpa.2015-0138-CP

Talmon GA, Czarnecki DK, Sayles HR (2015) Does how much a resident teaches impact performance? A comparison of preclinical teaching hours to pathology residents’ in-service examination scores. Adv Med Educ Pract 6:331–335. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S73127

Weiss V, Needlman R (1998) To teach is to learn twice. Resident teachers learn more. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 152(2):190–192

Simpson JF, Washington K (2012) The pathologist as a teacher. Am J Clin Pathol 138(3):320. doi:10.1309/AJCPDUMLZI2LT1SB

Kosemehmetoglu K, Tan A, Esen T et al (2010) Pathology residency training in Turkey from the residents’ point of view: a survey study. Turk Patoloji Derg 26(2):95–106. doi:10.5146/tjpath.2010.01005

Kulaylat AN, Qin D, Sun SX et al (2017) Perceptions of mistreatment among trainees vary at different stages of clinical training. BMC Med Educ 17(1):14. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0853-4

Karim S, Duchcherer M (2014) Intimidation and harassment in residency: a review of the literature and results of the 2012 Canadian Association of Interns and Residents National Survey. Can Med Educ J 5(1):e50–e57

Powsner SM, Costa J, Homer RJ (2000) Clinicians are from Mars and pathologists are from Venus. Arch Pathol Lab Med 124(7):1040–1046

Heffner DK (2008) Pathologists are from Mercury, clinicians are from Uranus: the perverted prospects for perceptual pathology. Ann Diagn Pathol 12(4):304–309. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2008.06.005

Schwartz RW, Jarecky RK, Strodel WE et al (1989) Controllable lifestyle: a new factor in career choice by medical students. Acad Med 64(10):606–609

Holland L, Bosch B (2006) Medical students’ perceptions of pathology and the effect of the second-year pathology course. Hum Pathol 37(1):1–8

Brooks EG, Paus AM, Corliss RF, Ranheim EA (2016) Enhancing preclinical year pathology exposure: the Angevine approach. Hum Pathol 53:58–62. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2016.02.006

Van Es SL, Grassi T, Velan GM et al (2015) Inspiring medical students to love pathology. Hum Pathol 46(9):1408. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2015.04.016

Ziai JM, Smith BR (2012) Pathology resident and fellow education in a time of disruptive technologies. Clin Lab Med 32(4):623–638. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2012.07.004

Van der Valk P (2016) Quality assurance in postgraduate pathology training the Dutch way: regular assessment, monitoring of training programs but no end of training examination. Virchows Arch 468:109–113. doi:10.1007/s00428-015-1895-4

Bhusnurmath SR, Bhusnurmath BS (2011) How can the postgraduate training program in pathology departments in India be improved? Indian J Pathol Microbiol 54(3):441–447. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.85072

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_European_countries_by_population (Access date: 22.03.2017)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Fatima Carneiro, Dr. Pedro Oliveira, Dr. GJA Offerhaus, Dr. Neli Basheska, the European Society of Pathology, and the Federation of Turkish Pathology Societies for their support for reaching participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was conducted in compliance with ethical standards.

Funding

No funding was received.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pehlivanoglu, B., Hassoy, H., Calle, C. et al. How does it feel to be a pathology resident? Results of a survey on experiences and job satisfaction during pathology residency. Virchows Arch 471, 413–422 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2167-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2167-2