Abstract

Background

Self-reported racial or ethnic discrimination in a healthcare setting has been linked to worse health outcomes and not having a usual source of care, but has been rarely examined among Asian ethnic subgroups.

Objective

We examined the association between Asian ethnic subgroup and self-reported discrimination in a healthcare setting, and whether both factors were associated with not having a usual source of care.

Design

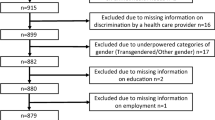

Using the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) 2015–2017, we used logistic regression models to assess associations among Asian ethnic subgroup, self-reported discrimination, and not having a usual source of care. Interactions between race and self-reported discrimination, foreign-born status, poverty level, and limited English proficiency were also analyzed.

Participants

Respondents represented adults age 18 + residing in California who identified as White, Black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian (including Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and Other Asian), and Other.

Main Measures

We examined two main outcomes: self-reported discrimination in a healthcare setting and having a usual source of care.

Key Results

There were 62,965 respondents. After survey weighting, Asians (OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.19–2.66) as an aggregate group were more likely to report discrimination than non-Hispanic Whites. When Asians were disaggregated, Japanese (3.12, 1.36–7.13) and Koreans (2.42, 1.11–5.29) were more likely to report discrimination than non-Hispanic Whites. Self-reported discrimination was marginally associated with not having a usual source of care (1.25, 0.99–1.57). Koreans were the only group associated with not having a usual source of care (2.10, 1.23–3.60). Foreign-born Chinese (ROR 7.42, 95% CI 1.7–32.32) and foreign-born Japanese (ROR 4.15, 95% CI 0.82–20.95) were more associated with self-reported discrimination than being independently foreign-born and Chinese or Japanese.

Conclusions

Differences in self-reported discrimination in a healthcare setting and not having a usual source of care were observed among Asian ethnic subgroups. Better understanding of these differences in their sociocultural contexts will guide interventions to ensure equitable access to healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Racial or ethnic discrimination is a known social determinant of health, associated with poor health outcomes [1,2,3] and low health service utilization [4]. Discrimination in a healthcare setting has been reported to a greater degree by Black, Asian, Hispanic, and Native American patients than non-Hispanic White patients [5]. Experiences with discrimination vary across racial minority groups, especially among Asians Americans [6, 7].

Asian Americans comprise more than 50 ethnic subgroups and 100 languages [8]. The heterogeneity of this population makes examination of discrimination and health by Asian ethnic subgroups necessary. Disaggregating data by ethnic subgroup has the potential to reveal health disparities such as higher risks of cervical cancer among Vietnamese women [9] and hypertension among Filipinos [10], both compared to non-Hispanic Whites. However, studies examining discrimination have mostly analyzed Asian Americans as an aggregate [11].

Discrimination is of interest as it has been shown to lead to fewer health care-seeking behaviors such as having a usual source of care. However, the association between experiences of racism and health care-seeking behavior has not been thoroughly explored in the literature [2]. Furthermore, there is a lack of knowledge regarding self-reported discrimination and its effects on having a usual source of care across Asian American ethnic subgroups. Du et al. described a usual source of care as being a “provider or place a patient consults when sick or in need of medical advice” [12]. According to Xu, studying the presence of a usual source of care can be helpful since it “is similar to having health insurance in the sense that both [health insurance and having a usual source of care] facilitate timely and adequate receipt of needed medical care” [13]. Having a usual source of care has been associated with various health care quality indicators including greater provider trust and satisfaction and increased receipt of preventative services [14, 15], and has been implicated in reducing healthcare disparities [16].

In this study, we analyzed both the association of race on self-reported discrimination and the association of race and self-reported discrimination on having a usual source of care. We focused our analysis among six Asian ethnic groups: Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and other Asian (which includes respondent self-identifying with two or more Asian ethnic groups). We hypothesized that differences in self-reported discrimination would be present among these different ethnic groups compared to non-Hispanic Whites. We further hypothesized that there would be an association between self-reported discrimination and not having a usual source of care, which would differ among Asian American ethnic subgroups [17].

Methods

Data Source

Data come from the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), a dual-frame random-digit-dialed survey of California residents via cellphones and landlines, with ongoing collection every two years [18]. Survey interviews were conducted in six languages: English, Spanish, Chinese (Mandarin and Cantonese dialects), Vietnamese, Korean, and Tagalog. Data from the sampling years 2015–2017 were analyzed, as these data contained the most up-to-date information about discrimination in a healthcare setting. Missing values in CHIS data files were replaced through multiple imputation by CHIS staff before public access [19]. There were a total of 62,965 survey respondents, of which 277 responded through proxy.

Variables

Two models with different outcomes were created: one with an outcome of racial or ethnic discrimination in a healthcare setting, and another with an outcome of not having a usual source care. Racial or ethnic discrimination in a healthcare setting was assessed with the answer (Yes/No) to the question “Was there ever a time when you would have gotten better medical care if you had belonged to a different race or ethnic group?” Not having a usual source of care was assessed by respondents’ response to the location of their usual source of care. In this study, respondents did not have a usual source of care if they reported their primary source of care was an emergency room, urgent care, or no usual source of care. This definition is similar to the definition used by the Centers for Disease Control [20]. While self-reported discrimination was the outcome in our first model, it was added as a predictor in the second model with an outcome of not having a usual source of care.

Each model was run with two sets of self-reported race variables. One set of race variables included Asian (in aggregate), non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic African American or Black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaskan Native (AIAN), and other race (where respondents indicated 2 or more races, where at most one of the identified groups is Asian). The other race set disaggregated Asian subgroups and included Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, and other Asian (which includes South Asian, Southeast Asian, and individuals who identify with 2 or more Asian subgroups).

Other variables were added in the multivariable analysis as covariates. These included self-reported gender, age (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70 +), citizenship (US-born citizen, naturalized, non-citizen), educational attainment (bachelor’s degree or greater, some college, high school or vocational school, and less than high school), rural or urban location, income as % of poverty level (> 300% poverty level, 200–299% poverty level, 100–199% poverty level, 0–99% poverty level), and English proficiency (very well, well, not well, not at all). Insurance status was assessed through type of insurance (employment-based, privately purchased, Medicaid only, Medicare only, Medicare and Medicaid, Medicare and others, other public insurance, or uninsured). Respondents’ health was assessed by their self-rated health status (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), and whether they had a chronic condition. The chronic conditions assessed and available within the CHIS dataset included asthma, diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension.

Analysis

Multivariable logistic regression models were created in R version 4.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the survey package [21]. Jackknife replicate weights were used to estimate percentages and standard errors to reflect the underlying population distribution within California. Descriptive statistics were first calculated for each of the covariates included in both models, with Chi-squared tests assessing differences in proportions. The first logistic regression model assessed the log odds of self-reported discrimination in Asian as an aggregate and Asian separated into component groups. The second logistic regression model assessed the log odds of having a usual source of care in Asians as an aggregate and Asian separated into component subgroups. In this second model, self-reported discrimination was included as a covariate. Significance was assessed at alpha < 0.05.

Interaction

The interactive effect of race with self-reported discrimination on not having a usual source of care was examined in additional logistic regression models. Interaction was also assessed for race with limited English proficiency, foreign-born status, and poverty (with an outcome of self-reported discrimination and an outcome of not having a usual source of care). To improve power when assessing for interaction, the covariates of interest other than race were included as dichotomized variables. Limited English proficiency was coded as any response other than “very well,” foreign-born status as any response other than “US-born citizen,” and poverty as response “0–99% federal poverty level.” The global effect of these terms was assessed using a Wald test. American Indian and Alaskan Native respondents were excluded when examining foreign-born status. The main effects of these interaction models are reported as an odds ratio (OR), while interactive effects are reported as a ratio of odds ratios (ROR).

Results

Respondent characteristics by self-reported discrimination are reported in Table 1. Self-reported discrimination was the highest in Black respondents out of all racial groups (13.9%). Japanese reported the greatest discrimination (6.9%), while Filipinos reported the least discrimination (2.4%) among Asian ethnic subgroups. Koreans and American Indian/Alaskan Natives were the groups with the greatest percentage of not having a usual source of care (28.7% and 25.1% respectively).

Table 2 shows the odds ratio (OR), after adjusting for covariates, of the outcome of self-reported discrimination in a healthcare setting. While Asians in aggregate were more likely to report discrimination than non-Hispanic Whites (OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.19–2.66), disaggregation by Asian ethnic subgroups shows that Japanese (OR 3.12, 95% 1.36–7.13), Koreans (OR 2.42, 95% CI 1.11–5.29), and Other Asian (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.28–4.64) were more likely to report discrimination compared to non-Hispanic Whites. Black (OR 5.41, 95% CI 3.48–8.41) and Hispanic (OR 2.03, 1.28–3.23) racial groups were also more likely to report discrimination than non-Hispanic Whites. Filipinos reported less discrimination, although this finding was not significant (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.42–1.83).

Table 3 shows the odds ratio, after adjusting for covariates, of not having a usual source of care. Self-reported discrimination was associated with not having a usual source of care, although marginally significant (OR 1.25, 95% CI 0.99–1.57). When considering Asians in aggregate, no racial group was associated with not having a usual source of care. When Asian ethnic groups were analyzed in disaggregate, Koreans were the only group among all racial and ethnic groups compared to non-Hispanic Whites who were more likely to report not having a usual source of care (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.23–3.60).

The only interactive effect found in these models between race with self-reported discrimination, limited English proficiency, foreign-born status, and poverty level was between race and foreign-born status with an outcome of self-reported discrimination in healthcare (p = 0.01, Table S1).

Table 4 shows the interaction terms for race with foreign-born status on an outcome of self-reported discrimination. Out of all the racial groups, foreign-born Chinese (ratio of odds ratios [ROR] 7.42, 95% CI 1.7–32.32) and foreign-born Japanese (ROR 4.15, 95% CI 0.82–20.95) were more associated with self-reported discrimination than being independently foreign-born and Chinese or Japanese. This change in mean percent predicted self-reported discrimination for different racial groups and foreign-born status is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Interaction between race and foreign-born status on self-reported discrimination in a healthcare setting through mean % predicted reported discrimination: California Health Interview Survey 2015–2017 (N = 62,965) weighted estimates. *Depicts significant interactive effect between race and foreign-born status compared to non-Hispanic White, †Depicts marginally significant interactive effect between race and foreign-born status compared to non-Hispanic White

Discussion

Different Asian ethnic subgroups, after adjusting for covariates, were associated with self-reported discrimination and not having a usual source of care. Among the ethnic subgroups, Korean and Japanese respondents were more likely to report discrimination in a healthcare setting. Koreans were the only ethnic subgroup associated with not having a usual source of care. Self-reported discrimination was associated with not having a usual source of care, although borderline insignificant. Finally, interaction analysis showed a significant interaction for Chinese or Japanese race with foreign-born status on an outcome of self-reported discrimination.

In this study, we found an association between Black and Hispanic groups and self-reported discrimination. Notably, Black respondents had the highest percentage of self-reported discrimination (~ 14%) and the greatest odds ratio of self-reported discrimination compared to non-Hispanic Whites (5.41) out of all racial groups. These findings corroborate previous findings of self-reported discrimination among Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Alaskan Native populations [22,23,24]. An association between Asian Americans as an aggregated group and perceived discrimination was also found in this study and corroborates previous studies [25,26,27]. However, this study further advances the literature by identifying an association between greater perceived discrimination and specific Asian ethnic subgroups, particularly Koreans and Japanese.

Unique historical, geographic, and cultural factors may moderate the role of day-to-day exposure in creating experiences and opportunities for discrimination, heightening awareness of discrimination in a healthcare setting [28, 29]. For example, Japanese Americans are more likely to intermarry and be more assimilated compared to other Asian ethnic subgroups [30]. Furthermore, Japanese American communities are dispersed throughout American cities and towns [31], as evidenced by the loss of Japantowns in California [32]. This lack of centralized Japanese communities and loss of protective ethnic enclaves may contribute to more day-to-day interactions with other racial populations, and thus more chances for discrimination. Similarly, many Korean communities across America are decentralized like Japanese communities, which may result in greater discrimination [33]. Korean Americans are also predominantly small business owners and may have more day-to-day interactions with other racial populations [34]. Conversely, Filipino Americans come from a predominantly English-speaking country and are therefore more acculturated due in part to the Philippines’ American colonialist history. In addition, the religious affiliation of most Filipinos is Catholic or Christian, which is more aligned with Christian ethics in the USA given historical roots in Spanish and American colonialism in the Philippines [35]. These factors may allow Filipinos to navigate more easily in American society, and thus identifying as Filipino may convey a protective effect against perceived discrimination in a healthcare setting as seen in this study. This benefit may be especially pronounced in a healthcare setting, since nearly a fifth of registered nurses in California are Filipino [36]. This discussion of historical, geographic, and cultural factors also speaks to a limitation—this study does not capture racial or ethnic patient-provider concordance, which has been linked to increased healthcare utilization and access [37]. Racial or ethnic concordance may be a confounding factor in our model, as it has been shown that Asian Americans prefer providers who are of the same race or ethnicity as them [38, 39].

We found an interactive effect of race with foreign-born status on self-reported discrimination in a healthcare setting for Chinese respondents and Japanese respondents. Previous studies support the notion that generational acculturation plays an important role in reducing perceived discrimination. Complex historical, political, and economic contexts of migration may also modify the relationship between foreign-born status and discrimination [40, 41]. Chinese respondents were the only group that showed a significant interactive effect, which may be due to the Chinese diaspora and unique factors affecting Chinese immigrants. However, a more practical explanation is that the Asian ethnic subgroup with the largest number of respondents was Chinese, allowing for sufficient power in our interaction analysis. As seen in Fig. 1, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese respondents had a visible difference in mean percent reported discrimination between foreign-born and not foreign-born respondents, suggesting that an interactive effect may be detectable with a larger sample size. Conversely, Filipinos showed a decrease in mean percent reported discrimination between foreign-born and not foreign-born. This finding may be explained again by Filipino American acculturation, coming from a predominantly English-speaking country.

There was a positive association between discrimination and not having a usual source of care after controlling for covariates, although this finding was borderline insignificant. This finding corroborates other studies which show that self-reported discrimination was associated with other health utilization measures such as usage of preventative health services [42] and delaying/forgoing medical care and prescriptions [11]. In general, no race or ethnic subgroup in our study was associated with not having a usual source of care after adjusting for covariates. This finding follows previous analyses that social factors explain disparities with not having a usual a source of care, instead of racial or ethnic differences [43, 44]. However, these studies did not examine disaggregated data by Asian ethnic subgroup. Our analysis of disaggregated Asian ethnic subgroups found that Koreans were associated with not having a usual source of care after adjusting for insurance coverage and self-reported discrimination—a finding consistent with a previous study [17]. Koreans have unique cultural factors that may lead them to not have a usual source of care. These factors include a reliance on traditional medicine, specific beliefs about the value of healthcare in the USA, and, most importantly, the reliance on medical tourism for care instead of care in the USA [45, 46].

It is important to place our findings in the context of post-Affordable Care Act (ACA) expansion in California. While self-reported discrimination in a healthcare setting has decreased within the last decade [47], this study shows that significant disparities among different racial groups persist. Furthermore, comparisons between pre- and post-ACA expansion have shown uneven improvements in health service utilization and access [17, 48, 49], as evidenced in our study by Koreans reporting not having a usual source of care. Even though the ACA reduced uninsurance rates among Asian Americans [50], our findings show that health disparities remain for Asian Americans which need to be addressed post-expansion. Furthermore, this study also highlights the necessity of Asian American data disaggregation to understand differences across Asian ethnic subgroups. These subgroups may experience unique healthcare disparities given cultural and historical differences [8].

The association between self-reported discrimination and not having a usual source of care further reinforces the finding that self-reported experiences of discrimination lead to decreased healthcare access [2, 5]. Our findings can be used to help develop interventions that meet the specific needs of Asian ethnic subgroups in a post-ACA era. Interventions already in development to reduce the negative effects of discrimination on health include value affirmation programs, anti-racism counter-marketing campaigns, and forgiveness exercises [5]. In particular, community-based organizations will play an essential role in reducing health disparities among Asian Americans by providing culturally appropriate resources specific to Asian ethnic subgroups [51,52,53,54].

There are limitations in this study. It was difficult to interpret results within the “Other Asian” category, as this category includes many Asian American populations such as South Asians (including Bangladeshi, Bhutanese, Goanese, Indian, Pakistani, and Sri Lankan Americans), Southeast Asians (including Thai, Burmese, Hmong, Malaysian, Cambodian, Indonesian, and Laotian Americans), and individuals identifying as two or more Asian subgroups. Since South Asian data were available only in the 2015–2016 CHIS dataset, a sensitivity analysis was conducted with South Asians included. South Asians reported no difference compared to non-Hispanic Whites with an outcome of self-reported discrimination as well as with an outcome of not having a usual source of care. Furthermore, there was no significant interactive effect between South Asians and foreign-born status on self-reported discrimination. There was also no change in significance or direction for most findings with the incorporation of South Asians in the logistic regression models. Much like Filipinos, many South Asians come from an English-speaking country, which may confer a protective effect when considering day-to-day interactions and opportunities for internalizing discrimination in a healthcare setting.

Another limitation is the cross-sectional survey design, which makes temporality difficult to ascertain. This will be an area of future study, for example, whether discrimination primarily leads to not having a usual source of care or vice versa. The use of a single question in this survey to measure self-reported discrimination does not capture chronicity, recurrence, severity, or duration. Discrimination is not a yes or no response, but a continuum that may have varying effects in different contexts [55]. Furthermore, self-reported discrimination is subject to reporting bias, although it can be useful to study because it has been linked to negative health outcomes [56]. Better methodology to capture self-reported discrimination is an active area of future research.

Finally, this survey sample is from California, limiting generalizability to the wider US population. However, CHIS has been essential in studying differences between Asian American ethnic subgroups, as approximately 30% of Asian Americans in the USA live in California. Given smaller population sizes in states other than California, Asian Americans in other states may experience more discrimination in a healthcare setting and may not have a usual source of care because they have less ethnic community and community-based organization support. Furthermore, California has one of the most generous medical and social safety nets, and Asian Americans in other states (especially those foreign-born) may not have adequate healthcare access comparatively.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight the need to incorporate disaggregated Asian American ethnic subgroups in analyzing self-reported discrimination in a healthcare setting and not having a usual source of care. Differences between Asian American ethnic subgroups and foreign-born status in self-reported discrimination and not having a usual source of care may be explained by unique sociocultural, geographic, and historical factors. Further studies are needed to better understand the differences between Asian American ethnic subgroups to ensure that all individuals in the USA have equitable access to healthcare.

Data Availability

The California Health Interview Survey is publicly available from the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CHIS:

-

California Health Interview Survey

- AI/AN:

-

American Indian/Alaskan Native

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- ROR:

-

Ratio of odds ratios

- SE:

-

Standard error

References

Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511.

Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA, Vu C. Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(Suppl 2):1374–88.

Gee GC, Ponce N. Associations between racial discrimination, limited english proficiency, and health-related quality of life among 6 asian ethnic groups in california. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):888–95.

Ben J, Cormack D, Harris R, Paradies Y. Racism and health service utilisation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2017;12(12):e0189900.

Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, Williams DR. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2015;11:407–40.

Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, Chae D. Racial discrimination and health among asian americans: evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:130–51.

Nadimpalli SB, Hutchinson MK. An integrative review of relationships between discrimination and asian american health. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44(2):127–35.

Islam NS, Khan S, Kwon S, Jang D, Ro M, Trinh-Shevrin C. Methodological issues in the collection, analysis, and reporting of granular data in asian american populations: Historical Challenges and Potential Solutions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(4):1354–81.

Ma GX, Fang C, Tan Y, Feng Z, Ge S, Nguyen C. Increasing cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese Americans: A community-based intervention trial. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(2 Suppl):36–52.

Ye J, Rust G, Baltrus P, Daniels E. Cardiovascular risk factors among Asian Americans: results from a National Health Survey. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(10):718–23.

Alcalá HE, Cook DM. Racial discrimination in health care and utilization of health care: a cross-sectional study of california adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(10):1760–7.

Du Z, Liao Y, Chen C-C, Hao Y, Hu R. Usual source of care and the quality of primary care: a survey of patients in Guangdong province, China. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):60.

Xu KT. Usual Source of care in preventive service use: a regular doctor versus a regular site. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1509–29.

Kim MY, Kim JH, Choi I-K, Hwang IH, Kim SY. Effects of having usual source of care on preventive services and chronic disease control: a systematic review. Korean J Fam Med. 2012;33(6):336–45.

Carpenter WR, Godley PA, Clark JA, Talcott JA, Finnegan T, Mishel M, et al. Racial differences in trust and regular source of patient care and the implications for prostate cancer screening use. Cancer. 2009;115(21):5048–59.

Corbie-Smith G, Flagg EW, Doyle JP, O’Brien MA. Influence of usual source of care on differences by race/ethnicity in receipt of preventive services. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(6):458–64.

Park S, Stimpson JP, Pintor JK, Roby DH, McKenna RM, Chen J, et al. The effects of the affordable care act on health care access and utilization among asian american subgroups. Med Care. 2019;57(11):861–8.

About CHIS | UCLA Center for Health Policy Research [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jul 18]. Available from: https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/about/Pages/about.aspx

Cooney D, Linville J, Williams D. Data Processing Procedures [Internet]. California Health Interview Survey; 2017 Oct. (CHIS 2015–2016 Methodology Report Series). Report No.: 3. Available from: https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/design/Documents/CHIS_2015-2016_MethodologyReport3_DataProcessing.pdf

Health Policy Data Requests - No Usual Source of Health Care Among Adults [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2021 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adults_no_source_health_care.htm

Lumley T. Package “survey” [Internet]. [cited 2021 May 3]. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survey/survey.pdf

Nong P, Raj M, Creary M, Kardia SLR, Platt JE. Patient-reported experiences of discrimination in the US Health Care System. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Dec 15;3(12):e2029650.

Benjamins MR, Middleton M. Perceived discrimination in medical settings and perceived quality of care: A population-based study in Chicago. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0215976.

Findling MG, Casey LS, Fryberg SA, Hafner S, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, et al. Discrimination in the United States: experiences of native americans. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(S2):1431–41.

Stepanikova I, Oates GR. Dimensions of racial identity and perceived discrimination in health care. Ethn Dis. 2016;26(4):501–12.

Shepherd SM, Willis-Esqueda C, Paradies Y, Sivasubramaniam D, Sherwood J, Brockie T. Racial and cultural minority experiences and perceptions of health care provision in a mid-western region. Int J Equity Health [Internet]. 2018 Mar 16 [cited 2021 Apr 20];17. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5857128/

Abramson CM, Hashemi M, Sánchez-Jankowski M. Perceived discrimination in U.S. healthcare: Charting the effects of key social characteristics within and across racial groups. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:615–21.

Chau V, Bowie JV, Juon H-S. The association of perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among chinese, korean, and Vietnamese Americans. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2018;24(3):389–99.

Goto SG, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Strangers still? The experience of discrimination among Chinese Americans. J Community Psychol. 2002;30(2):211–24.

Ono H, Berg J. Homogamy and intermarriage of japanese and Japanese Americans with whites surrounding world war II. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72(5):1249–62.

Paik SJ, Rahman Z, Kula SM, Saito LE, Witenstein MA. Diverse asian american families and communities: culture, structure, and education (Part 1: Why They Differ). 32

California Japantowns [Internet]. [cited 2021 Apr 27]. Available from: http://www.californiajapantowns.org/index.html

Lee T. Koreans in America: A Demographic and Political Portrait of Pattern and Paradox. Asia Policy. 2012;13:39–60.

Cook WK, Tseng W, Ko Chin K, John I, Chung C. Identifying vulnerable asian americans under health care reform: working in small businesses and health care coverage. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25(4):1898–921.

Gonzalez JJ. Filipino American Faith in Action [Internet]. New York University Press; 2009. Available from: https://doi.org/10.18574/9780814733257

Spetz J, Chu L, Jura M, Miller J. California board of registered nursing: 2016 survey of registered nurses. San Francisco: University of California; 2017. p. 202.

Meghani SH, Brooks JM, Gipson-Jones T, Waite R, Whitfield-Harris L, Deatrick JA. Patient–provider race-concordance: does it matter in improving minority patients’ health outcomes? Ethn Health. 2009;14(1):107–30.

Jang Y, Yoon H, Kim MT, Park NS, Chiriboga DA. Preference for patient–provider ethnic concordance in Asian Americans. Ethn Health. 2021;26(3):448–59.

Ma A, Sanchez A, Ma M. The impact of patient-provider race/ethnicity concordance on provider visits: updated evidence from the Medical expenditure panel survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(5):1011–20.

Szaflarski M, Bauldry S. The effects of perceived discrimination on Immigrant and refugee physical and mental health. Adv Med Sociol. 2019;19:173–204.

Portes A, Zhou M. The new second generation: segmented assimilation and its variants. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 1993;530(1):74–96.

Hausmann LRM, Jeong K, Bost JE, Ibrahim SA. Perceived discrimination in health care and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1679–84.

Ramamonjiarivelo Z, Comer-HaGans D, Austin S, Watson K, Matthews AK. Racial/ethnic and geographic differences in access to a usual source of care that follows the patient-centered medical home model: Analyses from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data. Patient Exp J. 2018;5(3):65–80.

Hammond WP, Mohottige D, Chantala K, Hastings JF, Neighbors HW, Snowden L. Determinants of usual source of care disparities among african american and caribbean black men: findings from the national survey of american life. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(1):157–75.

Jang SH. First-generation Korean immigrants’ barriers to healthcare and their coping strategies in the US. Soc Sci Med. 2016;1(168):93–100.

Jang SH. Medical Transnationalism: Korean Immigrants’ Medical Tourism to the Home Country [Internet]. CUNY Academic Works; 2017. Available from: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2133

Schulson LB, Paasche-Orlow MK, Xuan Z, Fernandez A. Changes in perceptions of discrimination in health care in california, 2003 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7):e196665.

Kominski GF, Nonzee NJ, Sorensen A. The affordable care act’s impacts on access to insurance and health care for low-income populations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38(1):489–505.

Chen J, Vargas-Bustamante A, Mortensen K, Ortega AN. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in health care access and utilization under the affordable care act. Med Care. 2016;54(2):140–6.

Park JJ, Humble S, Sommers BD, Colditz GA, Epstein AM, Koh HK. Health insurance for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders under the affordable care Act. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1128.

Ursua RA, Aguilar DE, Wyatt LC, Katigbak C, Islam NS, Tandon SD, et al. A community health worker intervention to improve management of hypertension among Filipino Americans in New York and New Jersey: A Pilot Study. Ethn Dis. 2014;24(1):67–76.

Schuster AL, Frick KD, Huh B-Y, Kim KB, Kim M, Han H-R. Economic evaluation of a community health worker-led health literacy intervention to promote cancer screening among Korean American women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(2):431–40.

Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, Nieman CL, Joo JH, Lin FR, et al. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):e3-28.

Kwon S, Patel S, Choy C, Zanowiak J, Rideout C, Yi S, et al. Implementing health promotion activities using community-engaged approaches in Asian American faith-based organizations in New York City and New Jersey. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(3):444–66.

Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):105–25.

Pascoe EA, Smart RL. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(4):531–54.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Gayane Yenokyan for statistical assistance.

Funding

This publication was made possible by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR), which is funded in part by Grant Number TL1 TR003100 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Johns Hopkins ICTR or University of Maryland, Baltimore, NCATS or NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

IRB approval was not needed as a public dataset with non-identifiable data was used.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

Preliminary findings from this study were presented at the Association for Clinical and Translational Science 2021 Annual Meeting.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Le, T.K., Cha, L., Gee, G. et al. Asian American Self-Reported Discrimination in Healthcare and Having a Usual Source of Care. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 10, 259–270 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01216-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01216-z