Abstract

While a number of studies have observed the effects of housing instability on health outcomes, fewer have emphasized pre-existing socioeconomic disparities in health and the influence of housing instability on subsequent health outcomes in the wake of the economic recession. Using national data on six adult health indictors and foreclosure data aggregated by census tract, this study examines the association between neighborhood housing insecurity and health outcomes, particularly focusing on various income levels and racial groups in about 200 U.S. metropolitan areas after the 2008 housing crisis. Results suggest that high levels of housing instability induced by high levels of foreclosed properties in certain neighborhoods were strongly associated with more health problems among residents, but the results varied according to the income level and the dominant racial group in these neighborhoods. With regard to income levels, adverse health conditions in lower income neighborhoods remained longer and became stronger than those in higher income neighborhoods. The findings also show variation among racial groups: While multiple health problems plagued all income levels in white tracts, more severe and worsening pre-existing health problems appeared in lower income minority tracts. In addition, neighborhood housing instability generated by mortgage foreclosures was strongly associated with heart-related diseases, particularly in middle-income White neighborhoods, and mental health problems, particularly in upper-income Hispanic tracts. Finally, among multiple health indicators, mental health problems were the most common health conditions during the U.S. economic recession. In light of the socioeconomic disparities in health, policy makers should establish effective policy tools that integrate health and urban and housing planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Great Recession of 2007–2009 was a significant economic downturn in American history, with an enormous burst of the housing bubble and surge in home foreclosures. Since the late 1990s, the deregulated government programs and rapid home value appreciation has led to the competitive purchasing of homes and proliferation of borrowers engaging in high-risk lending, the latter of which has resulted in widespread defaults on subprime loans. The 2008 housing crisis generated negative spillover effects on neighborhood socioeconomic environments, widening housing and health disparities across the USA [1, 2]. Some researchers have examined race/ethnicity or socioeconomic characteristics of neighborhoods as determinants of the decline of housing wealth and health equity [3,4,5,6]. Several researchers have found that severely compromised health outcomes were the result of the joint impact of housing deprivation and socioeconomic conditions [7]; few, however, have studied the association between neighborhood housing instability stemming from the economic recession and socioeconomic status on health outcomes by income and race jointly in the USA. Furthermore, no one has focused on the pre-existing socioeconomic disparities in health and the influence of housing instability on health outcomes after the economic recession.

The goal of this study is to examine the relationship between neighborhood housing insecurity and socioeconomic disparities in health in large U.S. cities in the wake of the economic recession. To do so, this study will begin by using tract-level home foreclosure rates to determine the associations between neighborhood housing instability and multiple health outcomes by four income levels in the aftermath of the crisis in 2014. After examining the decreasing trends of neighborhood-level foreclosure rates by the four income and four racial groups during the recovery from 2011 to 2014, it explores whether such reductions in the foreclosure rates were associated with health outcomes that differed according to the four income groups. Finally, it examines the associations between home foreclosure rates and health outcomes by diverse income groups within racial tracts simultaneously in 2014. The exploration of the association between high foreclosure rates and health outcomes according to the income group and race may provide useful information to policy makers who develop effective health and housing policies that improve sustainable neighborhoods during and after crises.

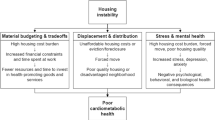

Evidence from a number of studies has revealed that housing instability such as highly concentrated mortgage delinquencies, home foreclosures, housing vacancies, and evictions in neighborhoods worsened health conditions. Most studies that took place during and after the 2007–2009 housing crisis have reported negative effects of housing instability on physical and mental health problems [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Of the studies that have examined the associations between foreclosures and health status, recent studies have focused on neighborhood-level foreclosures and health outcomes because the socioeconomic and physical context of neighborhoods also affected health outcomes [17,18,19,20]. While a number of studies have explored these associations during the crisis, few have studied the post-foreclosure and recovery period and its effects on neighborhood health outcomes [21].

Studies pertaining to the housing instability have found significant socioeconomic disparities during and after economic crises. In U.S. housing markets, they have found that discriminatory practices such as racial steering and redlining are strongly linked to racial residential segregation, but such practices also promote it [22, 23]. For example, real estate brokers are more likely to steer Black households to neighborhoods with larger Black and minority populations and lower home values than comparable white neighborhoods while encouraging White households to move to predominantly white neighborhoods (i.e., racial steering). Banks and lenders tend to refuse to lend to borrowers who belong to minorities and those who live in minority neighborhoods (i.e., redlining). Furthermore, segregation is exacerbated by federal housing policies such as public housing, concentrated primarily in lower income neighborhoods, and land regulations such as anti-density zoning, which prohibits lower income households from moving into wealthier communities [24, 25]. Therefore, during the 2007–2009 housing crisis, socio-economically disadvantaged neighborhoods were more readily exposed to predatory lenders, so the negative spillover effects of home foreclosures adversely impacted lower income and minoritized neighborhoods, their housing insecurity, and ultimately their health [2, 26,27,28]. During the post-foreclosure crisis, housing recovery was substantially slower in minoritized and economically strained communities, leading to widening housing disparities across neighborhoods, cities, and regions [2, 27, 29]. A number of studies have focused on the link between foreclosures and race and ethnicity and found that minoritized communities, in particular Black and Hispanic borrowers, were more vulnerable to the economic crisis [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. The cumulative cost of predatory lending to Blacks has been substantial, and such disadvantages continue to undermine their socioeconomic status [38]. Although class differences within racial groups are important to an understanding of the Great Recession [32], only a few studies have examined foreclosure variations by race and income group simultaneously [34].

Health studies that have examined socioeconomic disparities and housing instability, in general, they have found that minoritized and lower income populations who were already ill or unemployed struggled to pay their home loans and medical bills, and as a result, they experienced more home foreclosures and thus more worsening health problems [14, 39, 40]. In the larger context of the U.S. political economy, as neighborhood inequality built by racial and economic oppression has reverberated across generations, vulnerable populations have become more susceptible to adverse health outcomes after the crises [41, 42]. These vicious cycles have contributed to widening health disparities among populations of higher and lower socioeconomic status [13, 14]. Studies, however, have not addressed health outcomes according to various income levels within racial groups, typically divided by neighborhoods [3, 4, 43]. Responding to the issue that health disparities across various income groups interacting with races have not been thoroughly studied, Braveman et al. [4] examined socioeconomic disparities in health across five family income levels. They found that the lowest income- and lowest education-level groups had the poorest health status, that Blacks had worse health outcomes than Whites at all income and education levels, and that racial disparities in health were more common between Blacks and Whites.

In sum, although some studies have reported socioeconomic disparities in housing and health, none have linked home foreclosures and socioeconomic disparities in health post-crisis. In other words, previous studies have not addressed how neighborhood foreclosed properties affected health conditions by various income levels and racial groups. In addition, they have not acknowledged that pre-existing health disparities persisted in the wake of the housing crisis. To understand the association between neighborhood foreclosures and the complicated structure of socioeconomic disparities in health in U.S. cities, this study begins by examining disparities in health according to income group and then investigates income levels within racial groups jointly.

Data and Methods

Data

The health data for this study come from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which released its first 2014 health indicator data for the 500 largest U.S. cities in December 2016. Since then, the CDC has updated and published city- and census tract-level health data every year through the “500 Cities” website. This study uses 2014 estimates on six health outcomes: two overall health outcomes (i.e., physical and mental health that was impaired for more than 14 days), two heart-related diseases (i.e., coronary heart disease and stroke), and two lung-related diseases (i.e., asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). These selected health variables are also a mix of minor health outcomes (i.e., mental/physical health and asthma) and severe ones (i.e., coronary heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) that health study journals frequently report on. The 500 Cities Project used small area estimation methods for health data based on self-assessments by adults aged 18 years and older (See Appendix Table 6 for more explanations about definitions and measurements). The sources of the measurements were data collected from the CDC, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, U.S. Census Bureau 2010 data, and American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates 2009–2013 and 2010–2014 [44]. Measurements and their data sources, however, are limited in several ways. As the measurements of minor health outcomes (i.e., mental and physical health and asthma) are self-reported, the reliability and validity of the data are hard to assess, and as severe health indicators are based on the recollections of diagnoses reported by physicians and respondents, they might underestimate the true prevalence of health issues. Despite these limitations, the CDC 500 Cities health indicator dataset enables researchers to carry out comparable analyses of socioeconomic disparities in housing and health across the U.S. cities.

Neighborhood housing instability is measured by aggregated foreclosure data, which come from Black Knight, the largest mortgage market dataset in the USA. Black Knight collects data from the top ten mortgage services and 18 companies that collect mortgage payments for investors and lenders such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. This study converts ZIP code units of foreclosed properties from Black Knight into census tract-level units through HUD-USPS ZIP code crosswalk files [45] and then merges tract-level health outcomes in the 500 largest U.S. cities with tract-level home foreclosure rates.

Other explanatory data for census tract-level variables, including socioeconomic characteristics and housing and transportation infrastructures, come from ACS 5-year estimates 2011–2015, which also consist of metro-level variables, including demographic and economic data [46]. Among the metro-level control variables, the housing price index (HPI) comes from the CoreLogic Housing Price Index and amenity data from an index developed by McGranahan [47].

Methods

To examine the relationships between neighborhood foreclosures and health outcomes, this study has adopted multilevel modeling, a common method used in public health research [48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Unlike ordinary least squares, in which all observations are independent, multilevel models are suitable methods for this study because they allow for correlated observations when lower level areas are clustered within higher level areas [55]. This study uses a two-level random intercept and random slope model in which the census tract-level (level 1) is nested in the metropolitan level (level 2).

The dependent variables are six health outcomes: overall physical health, overall mental health, coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The health variables are transformed into logarithms that account for the skewed residual. The key independent neighborhood-level variables are the sum of foreclosed single-family homes in 2014 divided by the number of loans in 2014 in each census tract. Because of their skewed nature, foreclosure rates in the models are logged values.

Using log–log form cross-sectional models, this study examines the association between multiple health outcomes and aggregated tract-level foreclosures in 2014 in separate models run for each health outcome across the USA. Then, to further examine the associations by income level, it examines health conditions in higher and lower income neighborhoods, a traditional category of income groups. For the income categories, the study aggregates census tracts according to income levels defined by the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), a U.S. federal law that addresses the credit needs of low- and moderate-income communities: Low income denotes a median family income of less than 50% of that of a metropolitan family, a moderate income between 50 and 80%, a middle income between 80 and 120%, and an upper income 120% or more [56]. As a result, this study includes models run for 9513 higher income tracts, which were combined with upper- and middle-income tracts, and 7920 lower income tracts, which were combined with low- and moderate-income tracts. To examine income disparities in health across the four income groups, the study includes models run for each income level—4266 upper-income tracts, 5247 middle-income tracts, 4901 moderate-income tracts, and 3019 low-income tracts—for each health outcome.

Using a longitudinal approach, this study then adds a foreclosed home variable in 2011 divided by the number of loans in 2011 to the right side of the models to examine associations between a reduction in foreclosure rates and health outcomes. In other words, to examine the effects of reductions in foreclosure rates during the recovery from 2011 to 2014, it runs separate models for each health outcome by adding lagged foreclosure rates in 2011.

Finally, this study entails an examination of income and racial disparities in health by disaggregating each income tract by race: the White tract, defined as one whose share of White households is greater than 75%, and minority tracts, defined as one whose share of Black, Hispanic, or Asian households is greater than 50%.

Census tract-level neighborhood control variables include the percentages of Black, Asian, and Hispanic households in poverty, households with less than high school education, married households, uninsured households, median age and median family income, and the percentage of workers commuting over 30 min, all of which were commonly selected from health study variables since lower income and minoritized racial populations are more likely to live in unstable housing and disordered neighborhoods, resulting in worse health conditions [13, 16, 49, 53, 57,58,59].

Metropolitan-level control variables include housing and economic variables, including the size of the shock, the median home value, and unemployment rates. During the 2007–2009 crisis, lower home values and higher unemployment rates were more likely associated with adverse health outcomes in some regions. As more foreclosures was associated with a magnitude of the housing price boom and bust, which may have led to adverse health conditions, this study uses the size of the shock, an absolute value of change in the housing price boom (2000–2006) divided by change in housing price bust (2006–2011) in a metropolitan area during the housing market recession and recovery [1, 2, 60]. In addition, metropolitan-level urban form variables include metropolitan size, population growth, and the amenity index. In some regions, a larger city size and population growth were associated with more health problems, and fewer amenities have resulted in more dire health outcomes [57, 58]. Metropolitan size is calculated by the population of the metropolitan area, population growth by the percentage change in population during the recession and recovery from 2005 to 2014, and the amenity index, in which a higher value of the index represents more amenities [47]. The amenity index was aggregated into metropolitan level from county level.

Foreclosure Rates by Income and Race During and After the Economic Crisis

Figure 1 presents state-level home foreclosure rates during and after the foreclosure crisis. In the USA, average foreclosure rates were 1% or lower before the crisis and then began to surge in the West, the North, and the South from 2007 to 2009. During the peak in 2011 (Fig. 1(a)), foreclosed homes surged in the Midwest and the Northeast. During the recovery in 2014 (see Fig. 1(b)), they were lower but remained high in New York, New Jersey, and Florida.

Figure 2 presents the trajectory of tract-level foreclosure rates by income and race in the USA.Footnote 1 Figure 2(a) demonstrates that the high concentrations of foreclosures were more prevalent in lower income neighborhoods. When foreclosure rates are stratified by the four income levels of the CRA, the rates from 2000 to 2014 were generally high in low-income tracts, followed by moderate-, middle-, and upper-income tracts. The foreclosure trajectories of middle-income groups in Fig. 2(a) exhibit an unusual shape. From 2004 to 2009, the foreclosure rates of middle-income tracts were higher than those of moderate-income tracts. Moreover, from 2006 to 2007, the foreclosure rates of middle-income tracts were slightly higher than those in low-income tracts. These trends indicate that foreclosures on mortgages were more prevalent in middle-income tracts during the economic crisis from 2006 to 2007.

Figure 2(b) illustrates tract-level foreclosure trajectories by race. Foreclosure rates in Black and Hispanic tracts were substantially higher than those in White and Asian tracts. The foreclosure rates in Black tracts were much higher than those in Hispanic tracts, except in 2008 and 2009, indicating that Hispanic tracts were the victims of a significant number of foreclosures, particularly during the Great Recession from 2008 to 2009. Conversely, foreclosure rates in White tracts were far lower than those in Black and Hispanic tracts. Furthermore, foreclosure rates in Asian tracts were slightly lower than those in White tracts, except for those in early 2000 and between 2008 and 2012, indicating that Asian neighborhoods were the most stable during and after the economic crisis.

Results and Discussion

Table 1 lists descriptive statistics for variables in the 325 cities within the 200 metropolitan areas. This study further stratifies tracts to examine neighborhood characteristics in the four income groups and four racial groups. The results of ANOVA analyses show that the four income and racial groups were statistically distinctive in terms of health outcomes and socioeconomic and physical characteristics. Descriptive statistics show that health problems were more prevalent in low-income tracts, followed by moderate- and middle-income tracts, and those in upper-income tracts were less frequent. At the same time, health problems were more prevalent in Black tracts. The low-income tracts contained a larger share of Black and unmarried/younger aged households, a high level of poverty, and less-educated households.

The income columns in Table 1 show that the foreclosure rates in lower income tracts were much higher and declined even more than those of higher-income tracts. In addition, the racial columns in Table 1 show that foreclosure rates were higher in minority tracts.

Home Foreclosures and Health Outcomes by Income Level

The regression results of Table 2 show that neighborhood foreclosures represent a significant exploratory variable for all health outcomes, showing that residents’ proximity to foreclosed homes was positively associated with six health indicators. Among the health indicators, mental health was impacted most by home foreclosures. These results indicate that neighborhood housing instability plays a significant role in shaping public health and that mental health conditions are strongly influenced by the neighborhood housing instability.

The significance of the control variables varied but showed expected signs. For the racial variables, neighborhoods with more Blacks were positively associated with health problems whereas neighborhoods with more Hispanics and Asians were negatively associated. Socioeconomic control variables, including income, poverty, and education, were significantly associated with health indicators. Median family income variables were negatively associated with health outcomes, indicating that lower income households were more likely to be exposed to poor health. Neighborhoods with higher poverty and less-educated populations were strongly associated with health problems, confirming that socio-economically disadvantaged populations were more likely to have poor health. Nonetheless, the effects of neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics on health status were about two to three times as great in magnitude as the effects of neighborhood housing foreclosures.

Table 3 presents the estimation results of housing instability induced by foreclosures on health outcomes by tract income level in 2014. Column (a) presents the associations in two income groups, higher and lower income tracts, a traditional approach to comparing income levels. Overall, high foreclosure rates were strongly associated with health problems across both higher and lower income tracts, but the magnitudes and significances of their coefficients varied. While higher income tracts were more strongly associated with minor health outcomes such as overall mental health, overall physical health, and asthma, lower income tracts were more strongly associated with pre-existing and severe diseases, that is, coronary heart disease (CHD) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). It appears that residents of neighborhoods with historically low levels of foreclosure rates in higher income tracts may have experienced relatively more stress and depression, resulting in a stronger association between foreclosures and various minor health conditions and that residents in lower income tracts that had already been ill may have experienced a worsened health status because of rising foreclosure rates that led to an unstable economic environment in their neighborhoods.

Column (b) in Table 3 shows further stratified income tracts that highlight the association between home foreclosures and income disparities in health. One might question whether certain health conditions of residents in middle-income tracts, where the foreclosure crisis the hit hardest, worsened. Indeed, the results show this association to be the strongest, particularly with regard to mental health problems. As a high share of residents in middle-income tracts experienced more foreclosures during the crisis, those living in these tracts may have experienced more stress, leading to depression and other mental health problems. In addition, middle-income tracts showed a stronger association between foreclosures and overall physical health, strokes, and coronary heart disease than upper- and moderate-income tracts.

Changes in Foreclosure Rates and Health Outcomes by Income Group

Table 4 shows the estimation results of changes in foreclosure rates and health outcomes across the nation by income from 2011 to 2014. The results of column (a) suggest that some health problems in 2014 were triggered by foreclosure rates in 2011. The coefficients of the 2014 variables are positive and larger in magnitude than those of the 2011 variables, indicating that the effects of the peak in foreclosure rates in 2011 led to exacerbated health status 3 years later in 2014. Both 2011 and 2014 coefficients exhibit a statistical significance in three of the health-dependent variables, including overall mental health, overall physical health, and asthma. It appears that regardless of the reduction in foreclosure rates during the recovery, residents in neighborhoods where foreclosure rates remained high reported frequent health problems.

Column (b) shows that changes in housing foreclosure rates were strongly associated with more health problems in lower income tracts than in higher income tracts. Both 2011 and 2014 coefficients show a statistical significance in four health-dependent variables in lower income neighborhoods, including overall mental health, overall physical health, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In these lower income neighborhoods, health problems appeared in their residents immediately after the crisis began, remained longer, and then became stronger during the recovery. In higher income tracts, the only statistically significant health outcomes in both 2011 and 2014 were mental health conditions. As time passed, the mental health status became worse in both higher and lower income neighborhoods.

Column (c) presents the results for four income tracts. As the foreclosure crisis hit middle-income tracts the hardest, it might be possible that in middle-income tracts, changes in foreclosure rates were particularly associated with certain health outcomes. The results show that neighborhoods that were significantly associated with mental health problems were in middle-income, not upper-income tracts. The effects of foreclosures on the incidence of impaired mental health in middle-income tracts were about twice as great in magnitude as those in low- and moderate-income tracts.

Home Foreclosures and Health Outcomes by Both Income and Race

Table 5 presents the regression results for the effects of foreclosures on health outcomes by income and race simultaneously. The results show that lower income minority neighborhoods were vulnerable to housing instability, which led to adverse health outcomes. Black tracts suffered from all six health outcomes, all of which were reported in low- and moderate-income tracts. Low-income Black tracts were strongly associated with a significant incidence of pre-existing and severe diseases such as coronary heart disease, stroke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These results confirm that Blacks, particularly those in low- and moderate-income tracts, experienced severe and worsening pre-existing health conditions during the recession. Furthermore, while the association between foreclosures and mental health was statistically significant in the upper-income Hispanic tracts, the association between foreclosures and severe health problems such as stroke and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was statistically significant in low- and moderate-income Hispanic tracts.Footnote 2

Similar to the results of national analyses, the results of this study show that White tracts experienced multiple and minor health problems across income levels. The incidence of minor health problems was more than twice as strong in magnitude in low-income White tracts as it was in other income tracts. In middle-income White tracts, the incidence of coronary heart disease and stroke was statistically significant, possibly because the foreclosure crisis severely compromised the health of residents in these tracts.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

While a number of studies have observed the effects of housing instability on health outcomes, fewer have studied the relationship between foreclosures and health outcomes according to neighborhood income and race in the wake of economic recessions, and few have focused on pre-existing health disparities within the neighborhood context across U.S. cities. Thus, to fill the research gap, this study has examined the association between neighborhood-level foreclosures and six health outcomes across the four income groups and races in more than 300 cities after the U.S. economic crisis. It finds that neighborhood housing instability stemming from home foreclosures generated worse health outcomes and that statistical significances varied by income and race: Health problems in lower income neighborhoods remained longer and became stronger in the wake of the economic crisis than they did in higher income neighborhoods. More importantly, among the four income and racial groups, low- and moderate-income Blacks experienced worsening pre-existing health conditions, which demonstrates that neighborhood housing insecurity during the economic recession led to further widening socioeconomic disparities in health. This study also finds that corresponding to the highest foreclosure rates in middle-income neighborhoods during the crisis, residents in middle-income tracts had the strongest association with mental health problems, which were greater in magnitude than those in low- and moderate-income tracts. Among the four income and racial groups, middle-income White neighborhoods showed a strong association between housing instability and heart-related diseases and upper-income Hispanic tracts showed a strong association between housing stability and mental health problems.

This study sought to contribute to the literature on neighborhood housing instability on health outcomes during the economic recession. While most studies have found health disparities between higher and lower income groups, this study further stratified income levels and investigated housing and health conditions across four income levels (low-, moderate-, middle-, and upper). The results of this study have shown strong evidence for the previous long-established finding that low-income neighborhoods suffering housing insecurity in the wake of the economic downturn were substantially subject to worsened and severe health conditions.

This study has contributed to the literature on economic disparities in housing and health resilience. As lower income neighborhoods hit hard by the housing crisis were less resilient and recovered more slowly than wealthier neighborhoods [61], they were less resilient to the adverse health effects triggered by the depressed economy, which indicates that multiple health problems appeared in their residents immediately, remained longer, and recovered slowly during the recession. As housing disparities between poor and wealthy tracts widened during the recession, health disparities also became larger.

This study has also contributed to the literature on racial disparities in housing and health, confirming that housing instability and health problems were disproportionately concentrated in neighborhoods with high shares of Blacks during the economic downturn. Furthermore, low- and moderate-income Black neighborhoods exhibited the worst health conditions of all four income and racial groups. The foreclosure crisis hit higher income neighborhoods hard during the housing crisis [34], but the effects of housing instability on health outcomes varied across higher income groups: Residents of upper-income Hispanic neighborhoods were more likely to suffer from mental health problems, and residents of middle-income White neighborhoods were more likely to suffer from heart-related diseases.

The findings from this study suggest several policy and research implications. Policy makers should establish policies that mitigate neighborhood health disparities stemming from neighborhood housing instability during and after an economic crisis. As shown in the findings of this study, neighborhood housing instability resulting from home foreclosures led to worsening health conditions and widening socioeconomic disparities in health across neighborhoods. First and foremost, to mitigate housing and health disparities, local and regional governments should devote more attention to vulnerable populations and neighborhoods during and after an economic recession. Although health problems that stemmed from housing insecurity were common across various income and racial groups, residents in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods with pre-existing health issues experienced even more severe and worsening health outcomes in the wake of the recession. Thus, policy makers should systematically plan relief steps to ensure housing and health policy directions that help vulnerable populations are effective. During an economic crisis, policy makers should take prompt action to identify low-income and minority households requiring assistance. Once policy makers identify disadvantaged individuals who need housing subsidies and with pre-existing health conditions, they should distribute financial resources promptly to ensure that these individuals are able to remain in their homes by preventing foreclosures and to pay medical bills by preventing an exacerbation pre-existing health conditions. Such policy solutions, such as people-based policy regulations, might include direct income support. As the health problems of vulnerable populations worsened immediately and remained longer, direct income support for those with pre-existing health problems should have been provided promptly and continued until the end of the recession.

Another approach to minimizing the effects of economic shocks on neighborhood housing and health disparities would be to establish long-term strategies. For one, policy makers could establish place-based housing and health policies by actively integrating health and urban planning. For example, they could establish health impact assessment programs that evaluate neighborhood developments to determine whether they have any potential to cause health consequences or impact health disparities. The assessment components of these health programs included mostly physical environment factors, and housing decisions has been increasing [62]. In addition to these housing sectors, neighborhood income and racial characteristics could also be important to assessing residents’ health. As the results of this study imply that income and racial residential segregation may be a major contributor to racial disparities in health and wellbeing, policy makers could aim to achieve racial diversity, which could reduce the extent of housing segregation. They also include a goal of using planning tools to create more economically diverse neighborhoods by assigning low-income families to wealthy neighborhoods and encouraging mixed income development in their neighborhoods. Through such efforts, planners and health policy makers should continue to discuss effective solutions for the creation of sustainable and healthy neighborhoods as the long-term strategies.

Health policy makers should also plan to provide sufficient and accessible medical services during and after a recession. As the results of this study showed, neighborhood housing conditions played an important role in shaping residents’ health, particularly their mental health. Moreover, even during the housing recovery period, people continued to report frequent health problems, showing that the adverse effects of the recession on health outcomes remained longer than on housing markets. Therefore, even after a crisis, policy makers should provide more accessible medical centers or clinical services near or in neighborhoods. They should provide clinical services with different approaches to health care according to neighborhood characteristics. Residents both in higher and lower income neighborhoods experienced more health problems during the recession but did so in different ways. While residents in higher income neighborhoods were more likely to report minor health problems, those in lower income neighborhoods were more likely to suffer from pre-existing and severe health problems. Thus, policy makers should designate the establishment of more temporal medical or consulting organizations near neighborhoods. They should also provide more medical benefits such as medication vouchers to residents in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods in proportion to the severity of their conditions.

With an enhanced understanding of socioeconomic disparities in health, policy makers should be able to more effectively respond to the effects of neighborhood housing instability on health outcomes. While the physical conditions of housing in some Asian cities, for example, are considered stronger determinants of health outcomes than socioeconomic characteristics [6], this study found a significant association between socioeconomic factors and public health in the USA. Thus, with an accumulation of more national health data, further studies could more comprehensively explain the relationship between housing and health across incomes and races and across neighborhoods and regions. Studies that identify such associations would provide more effective urban policy strategies for mitigating both housing and health issues.

Notes

Foreclosure rates represent all foreclosed mortgages relative to all active mortgages.

Asian tracts were not statistically significant across the income levels, possibly the result of a small sample size, and so they are not included in the table of the regression analyses.

References

Wang K. Housing market resilience: neighborhood and metropolitan factors explaining resilience before and after the U.S. housing crisis. Urban Stud. 2019a;56(13):2688–708.

Wang K. Neighborhood foreclosures and health disparities in the U.S. cities. 2020;7:102521 [Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264275118312411]. Accessed 11 March 2021.

Issacs SL, Schroeder SA. Class—the ignored determinant of the nation’s health. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(2):1137–42.

Kawachi I, Daniels N, Robinson DE. Health disparities by race and class: why both matter. Health Aff. 2005;24(2):343–52.

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S):186–96.

Reid CK, Bocian D, Li W, Quercia RG. Revisiting the subprime crisis: the dual mortgage market and mortgage defaults by race and ethnicity. J Urban Aff. 2016;39(4):469–87.

Wan C, Su S. Neighborhood housing deprivation and public health: theoretical linkage, empirical evidence, and implications for urban planning. Habitat Int. 2016;57:11–23.

Bernal-Solano M, Bolívar-Muñoz J, Mateo-Rodríguez I, Robles-Ortega H, Fernández-Santaella M, Mata-Martín J, Vila-Castellar J, Daponte-Codina A. Associations between home foreclosure and health outcomes in a Spanish city. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(6):981.

Burgard SA, Seefeldt KS, Zelner S. Housing instability and health: findings from the Michigan Recession and Recovery Study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2215–24.

Cagney KA, Browning CR, Iveniuk J, English N. The onset of depression during the great recession: foreclosure and older adult mental health. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:498–505.

Currie J, Tekin E. Is there a link between foreclosure and health? Am Econ J Econ Pol. 2015;7(1):63–94.

Gili M, Roca M, Basu S, McKee M, Stuckler D. The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur J Pub Health. 2013;23(1):103–8.

Houle JN. Mental health in the foreclosure crisis. Soc Sci Med. 2014;118:1–8.

Libman K, Fields D, Saegert S. Housing and health: a social ecological perspective on the U.S. foreclosure crisis. Hous Theory Soc. 2012;29(1):1–24.

Pevalin DJ. Housing repossessions, evictions and common mental illness in the UK: results from a household panel study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(11):949–51.

Pollack CE, Lynch J. Health status of people undergoing foreclosure in the Philadelphia region. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1833–9.

Christine PJ, Moore K, Crawford ND, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Sanchez BN, Seeman T, Diez Roux A. Exposure to neighborhood foreclosures and changes in cardiometabolic health: results from MESA. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(2):106–14.

Downing J, Laraia B, Rodriguez H, et al. Beyond the great recession. Was the foreclosure crisis harmful to the health of individuals with diabetes? Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(6):429–35.

Duran AC, Zenk SN, Tarlov E, Duda S, Smith G, Lee MJ, Berbaum ML. Foreclosure and weight gain: differential associations by longer neighborhood exposure. Prev Med. 2019;118:23–9.

Schootman M, Deshpande AD, Pruitt SL, Jeffe DB. Neighborhood foreclosures and self-rated health among breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:133–41.

Arcaya M. Invited commentary: foreclosures and health in a neighborhood context. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(6):436–9.

Turner MA, Ross SL. How racial discrimination affects the search for housing? In: Briggs XS, editor. The geography of opportunity: race and housing choice in metropolitan America. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2005.

Wyly EK, Hammel DJ. Gentrification, segregation, and discrimination in the American urban system. Environ Plan A. 2004;36:1215–41.

Rosenthal SS. Old homes, externalities, and poor neighborhoods: a model of urban decline and renewal. J Urban Econ. 2008;63:816–40.

Rothwell J, Massey D. The effect of density zoning on racial segregation in U.S. urban areas. Urban Aff Rev. 2009;44(6):779–806.

Crump J, Newman K, Belsky ES, Ashton P, Kaplan D, H., Hammel, D, J., & Wyly, E. Cities destroyed (again) for cash: forum on the U.S. foreclosure crisis. Urban Geogr. 2008;29:745–84.

Ong P, Spencer J, Zonta M, Nelson T, Miller D, Heintz-Mackoff J. The economic cycle and Los Angeles neighborhoods; 1987–2001. Report to the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation. 2003.

Williams S, Galster G, Verma N. The disparate neighborhood impacts of the great recession: evidence from Chicago. Urban Geogr. 2013;34(6):737–63.

Ellen EG, Madar J, Weselcouch M. The foreclosure crisis and community development: exploring REO dynamics in hard-hit neighborhoods. Hous Stud. 2014;30(4):535–59.

Been V, Ellen I, Madar J. The high-cost of segregation: exploring racial disparities in high-cost lending. Fordham Urban Law J. 2009;36:361–84.

Cheng P, Lin Z, Liu Y. Racial discrepancy in mortgage interest rates. J Real Estate Financ Econ. 2014;51:101–20.

Hyra DS, Rugh JS. The US great recession: exploring its association with black neighborhood rise, decline and recovery. Urban Geogr. 2016;37:700–26.

Hyra DS, Squires GD, Renner RN, Kirk DS. Metropolitan segregation and subprime lending. Hous Policy Debate. 2013;23(1):177–98.

Faber JW. Racial dynamics of subprime mortgage lending at the peak. Hous Policy Debate. 2013;23(2):328–49.

Lacy K. All’s fair? The foreclosure crisis and middle-class Black (in)stability. Am Behav Sci. 2012;56(11):1565–80.

Massey DS, Rugh JS, Steil JP, Albright L. Riding the stagecoach to hell: a qualitative analysis of racial discrimination in mortgage lending. City Community. 2016;15(2):118–36.

Niedt C, Martin I. Who are the foreclosed? A statistical portrait of America in crisis. Hous Policy Debate. 2013;23(1):159–76.

Rugh JS, Albright L, Massey DS. Race, space, and cumulative disadvantage: a case of the subprime lending collapse. Soc Probl. 2015;62(2):186–218.

Fields D, Libman K, Saegert. Turning everywhere, getting nowhere: experiences of seeking help for mortgage delinquency and their implications for foreclosure prevention. Hous Policy Debate. 2010;20:647–86.

Keene DE, Lynch JF, Baker AC. Fragile health and fragile wealth: mortgage strain among African American homeowners. Soc Sci Med. 2014;118:119–26.

Michener J. Fragmented democracy: medicaid, federalism, and unequal politics. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2018.

Trounstine J. Segregation by design: local politics and inequality in American cities. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2018.

Krieger N, Chen JT, Ebel G. Can we monitor socioeconomic inequalities in health? A survey of US health department’s data collection and reporting practices. Public Health Rep. 1997;112(6):481–91.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 500 cities: local data for better health. 2016. [Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/500cities/]. Accessed 20 Jul 2018.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). HUD USPS ZIP Code crosswalk files. 2019. [Available from https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/usps_crosswalk.html]. Accessed 3 Aug 2019.

U.S. Census Bureau. American community survey (ACS). 2019. [Available from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/]. Accessed 3 Aug 2019.

McGranahan, D. Natural amenities drive rural population change. U. S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Agricultural Economic Report No. 781. 1999. [Available from https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/41047/13201_aer781.pdf?v=42061]. Accessed 15 Mar 2018.

Diez-Roux AV. Multilevel analysis in public health research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:171–92.

Duncan J, Moon. Do places matter? A multilevel analysis of regional variations in health-related behavior in Britain. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37:725–33.

Duncan C, Jones K, Moon G. Health-related behavior in context. A multilevel modeling approach. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42(6):817–30.

Kemppainen T, Elovainio M, Kortteinen M, Vaattovaara M. Involuntary staying and self-rated health: a multilevel study on housing, health and neighbourhood effects. Urban Stud. 2019. 004209801982752. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019827521.

LeClere FB, Rogers RG, Peters K. Neighborhood social context and racial differences in women’s heart disease mortality. J Health Soc Behav. 1998;39(2):91–107.

Ross C, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(3):258–76.

Subramanian SV. The relevance of multilevel statistical methods for identifying causal neighborhood effects. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1961–7.

Kreft I, Leeuw J. Introducing multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc; 1988.

U.S. Government Publishing Office. Electronic code of federal regulations: Title 12 Banks and Banking. 2018. [Available from http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=301e3bf4ada99f871833da1a91f51911&node=se12.3.228_112&rgn=div8]. Accessed 28 Jul 2018.

Cohen DA, Spear S, Scribner R, Kissinger P, Mason K, Wildgen J. Broken windows and the risk of gonorrhea. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(2):230–6.

Wang K, Immergluck D. The geography of vacant housing and neighborhood health disparities after the U.S. foreclosure crisis. Cityscape. 2018;20(2): 145–170. [Available from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26472173]. Accessed 11 Mar 2021.

Arcaya M, Glymour MM, Chakrabarti NA, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Effects of proximate foreclosed properties on individuals’ systolic blood pressure in Massachusetts, 1987–2008. Circulation. 2014;129(22):2262–8.

Carson RT, Dastrup SR. After the fall: An ex post characterization of housing price declines across metropolitan areas. Contemp Econ Policy. 2013;31(1):22–43.

Wang K. Neighborhood housing resilience Examining changes in foreclosed homes during the U.S. housing recovery. Hous Policy Debate. 2019b;29(2):296–318.

Bever E, Arnold KT, Lindberg R, Dannenberg AL, Morley R, Breysse J, Pollack Porter KM. Use of health impact assessments in the housing sector to promote health in the United States, 2002–2016. J Housing Built Environ. 2021;36:1277–97.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta for supporting this research through its co-op researcher program with unique datasets. All opinions are those of the author, and any errors in this study are her sole responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, K. Housing Instability and Socioeconomic Disparities in Health: Evidence from the U.S. Economic Recession. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 9, 2451–2467 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01181-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01181-7