Abstract

HIV-related stigma is a negative attitude or behaviour towards persons living with HIV, and is detrimental to effective care, management, and treatment of HIV. Using a revised 10-item stigma scale, we compared levels of HIV-related stigma and its correlates among Black women living with HIV in Ottawa, Canada, and Miami, FL, USA, with those in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. HIV-related stigma scores were calculated, with a maximum score of 10 and averaged 4.71 in Ottawa, 5.06 in Miami, and 3.78 in Port Harcourt. No significant difference in HIV-related stigma scores between Ottawa and Miami. HIV-related stigma was significantly (p < 0.05) higher among women in the North American cities compared with women in the African city. Hierarchical linear modelling shows that psychosocial variables contributed to variations in HIV-related stigma in Ottawa (22.3%), Miami (36.3%), and Port Harcourt (14.1%). At p < 0.05, discrimination was a significant predictor of increased HIV-related stigma in Ottawa (β = 0.077), Miami (β = 0.092), and Port Harcourt (β = 0.068). Functional social support had a significant diminishing effect on HIV-related stigma in Miami (β = − 0.108) and Port Harcourt (β = − 0.035). Tackling HIV-related sigma requires sociocultural considerations within specific regional and national contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stigma due to HIV is the negative assumptions, beliefs, feelings, attitudes, abuse, and maltreatment directed towards individuals or groups of persons living with the disease, groups associated with people living with HIV (PLWH), and other populations at higher risk of HIV infection [1]. This definition is consistent with the theory of social stigma, which defined stigma as an attribute, behaviour, or reputation socially discrediting in a particular way, causing a person to feel undesirable [2]. In its most inescapable and deleterious form, HIV-related stigma, occurs when a person living with HIV integrates negative attitudes into their own self-concept [3,4,5,6,7].

Stigma affects the life and well-being of PLWH. Studies have shown that the relative lack of social acceptance of PLWH is particularly detrimental to the fight against HIV/AIDS, because it undermines uptake of voluntary HIV testing [8], disclosure of serostatus [9], retention in care, and adherence to anti-retroviral therapy [4, 10].

Women are especially susceptible to HIV-related stigma [11,12,13,14]. This, in part, is because of gendered discourses that portray women as ‘vectors’, ‘diseased’, and ‘prostitutes’ [15, 16]. Pregnant and parenting women living with HIV also often encounter higher and more intense levels of stigma due to judgemental opinions about HIV transmission during pregnancy. While HIV treatment reduces the risk of transmission of the virus to the foetus to as low as 1% or less, the feeling of being judged prevents pregnant women living with HIV from seeking and utilizing services that avert vertical HIV transmission from the mother to the unborn child [6]. When a woman living with HIV becomes pregnant, stigma can lead to rejection from friends, family, and society, or can lead to feelings of uncertainty and loss, low self-esteem, fear, anxiety, and depression [3,4,5, 17, 18].

With advancement in HIV prevention and treatment, infant feeding guidelines for HIV-positive women have evolved over the years. In 2010, WHO recommended exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months, provided the HIV-positive mother and/or baby are taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) during the same time period [19]. However, this guideline still recommended avoiding breastfeeding if formula feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable and safe (AFASS) [19]. Consequently, implementation of the guidelines varies globally. For instance, while western countries like Canada and the USA recommend exclusive formula feeding (EFF) [20, 21], low middle income countries like Nigeria recommend exclusive breastfeeding [19, 22]. In 2016, WHO guidelines recommended that HIV-positive mothers who adhere to ART can breastfeed for at least 12 months and may continue breastfeeding for up to 24 months or longer [23]. Conflicting guidelines creates a lot of tension for Black women especially those living in western countries because of the significant influence of cultural norms on infant feeding choices. For instance, when women living with HIV opt for formula feeding instead of breastfeeding as a way of adhering to national guidelines, they may experience stigma [24]. If they choose to breastfeed, they may also experience stigma [25, 26]. These factors make HIV stigma a more complex issue among migrant women of African Caribbean descent relative to non-migrant populations.

Many studies have examined the psychosocial and public health impacts of HIV-related stigma [3, 5,6,7]. Studies that compared levels of HIV-related stigma and its determinants across cities in different countries are rare; we identified one study that compared HIV-related stigma in four countries [27]. However, this study compared four countries from the Global South. In contrast, our study compared cities in two countries in the Global North (Canada and USA) with a city in a country in the Global South (Nigeria). Although these three cities have their unique place-based characteristics such as their sizes and the organization of the healthcare systems, they also have similar elements such as migration patterns that make sites comparison necessary. As a result of these place-based characteristics, there may be differences in the set of factors influencing stigma in each city, necessitating separate model of analysis for each city.

Although HIV-related stigma is universal, the magnitude or intensity of negative attitudes towards PLWH varies across societies. In addition, the ways in which HIV-related stigma is manifested and interpreted may vary across cultural and historical contexts. As a social construct, HIV-related stigma takes different shapes and forms across place, time and space. We could not find studies that compared experiences of HIV-related stigma in the ‘North-South’ perinatal and global health contexts. This paucity of cross-national studies of HIV-related stigma is a significant knowledge gap that may impede evidence-based care for this population. The purpose of this study was to compare levels of HIV-related stigma and examine its predictors with particular focus on Black mothers who self-identified as living with HIV in Ottawa, Canada; Port Harcourt, Nigeria; and Miami, FL, USA. These mothers were reached at specific venues of their events using established social networks to seek their informed consents.

Methodology

This paper is based on data from a larger Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) funded mixed-method study informed by community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach. CBPR is increasingly recognised as an interdisciplinary mixed method research design [28], with an epistemological stance that embraces community members as a collaborative partner and knowledge co-creators, and owners [29]. This design facilitated authentic engagement of the communities and helped the team to establish rapport and trust prior to survey administration. The research questions originated from women living with and impacted by HIV in the ACB community. Some of these women were research team members and participated in all phases of the research planning and implementation.

Study Sites Description

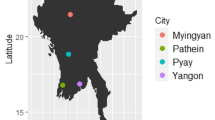

Three study sites were selected to capture the perspectives of Black women from diverse geographical and ethno-cultural backgrounds in the global North and South, which are influenced by differing patterns and histories of HIV infection, and infant feeding traditions. Ottawa, Canada, is a large metropolitan region with a long history of hosting foreign embassies (nation’s capital) and diverse immigrant groups. Of the visible minority population in Canada, 54% make Ontario their home and account for about 19.1% of the population of the province [30]. In Ontario, ACB people infected with HIV through heterosexual contact account for over 18% of the estimated total of all HIV-positive people, even though ACB people as a whole make up only 4.3% of the province’s population [31]. About 40% of the estimated numbers of ACB people infected with HIV through heterosexual contact are women [31]. Port Harcourt, Nigeria, is the capital of Rivers State in the South-South region of Nigeria with a predominantly Black population and carries a heavy burden of HIV and AIDS. The state has a projected population of 6.2 million, prenatal HIV prevalence of 6.0%, and population prevalence of 3.6% [32]. Also, occurrence of high-risk sexual behaviour and transactional sex in the state is rated third highest in the country [32, 33]. The state is well known for its booming oil industry and high commercial activities, which attracts continuous influx of sex workers (brothel-based and non-brothel-based). Sex worker camps often spring up around land oil rigs and oil-bearing communities, and there is increasing spread of brothels and club houses to the rural areas. HIV prevalence among the female sex workers was 17% for brothel-based and 27% non-brothel based. Miami, Florida, has one of the largest Black African populations in the USA. It is a renown multi-cultural hub of Florida and the Americas with the largest percentages of those who claim a foreign ancestry living its communities such as Miami-Dade [34, 35]. Women of colour, particularly Black women, are disproportionately affected by HIV, accounting for the majority of new HIV infections, women living with HIV, and HIV-related deaths among women in the USA [36]. In 2013, 20% (N = 9278) of all new HIV infections diagnosed in the USA were women [37], and Black women were 13 times more likely to be HIV-infected than White women; Black women accounted for nearly two-thirds (64%) of all estimated new HIV infections among women in the USA [38].

In Canada and the USA, where formula is AFASS, perinatal guidelines advice against breastfeeding while exclusive breastfeeding is recommended in low-resource setting like Nigeria. Despite these WHO-based guidelines, there are cultural tensions for Black women especially those who feel striped of sense of motherhood because they are not allowed to breastfeed. There are also others who experience ethical tension between the women’s right to make the personal and informed decision about infant feeding choice and the infant’s right to reduce the risk of acquiring HIV through breastfeeding. These diverse viewpoints highlight important comparative dimensions with respect to the ethno-cultural groups and healthcare access. And these have implications for future programming and interventions that would reach a wider audience.

Data Collection

Due to the sensitive nature of HIV and difficulty of the Black women self-identifying as persons living with HIV as well as the relatively small population of ACB people in Ottawa, it was problematic to use random sampling. Therefore, venue-based sampling was employed to recruit participants from venues and social events where Black women would normally gather from November 2016 to March 2018. These included churches and mosques, community resource centres, public health facilities, AIDS service organizations, immigrant support agencies, pre-schools, physician offices, family gatherings, and other community events. Recruitment were conducted through intermediaries, in many cases with our collaborators and their staff (under guidance) introducing the study and gaining consent for subsequent contact by a study team member. In addition, our team members used existing community research networks that had been established over several years.

Ethics approvals from affiliated institutions such as the University of Ottawa Research Ethics Board (REB), Florida International University Institute of Research Services (IRS), and University of Port Harcourt Research Committee were obtained. This was followed by the research survey conducted through the support of the project’s trained research coordinators, graduate students and research assistants who administered the surveys using paper or electronic format based on participants’ preference. All study information materials were translated into French for Ottawa site, and interpreters were used when necessary to obtain informed consent and ensure ease of communication. For confidentiality and anonymity, all participant data were given pseudonyms using study-generated identification. Overall, sample size comprised of a cross-sectional multi-country survey of the following numbers of Black mothers living with HIV between the ages 18 and 49 years—Ottawa, n = 89; Miami, n = 201; and Port Harcourt, n = 400. All the women/mothers were of the African descent either living in the continent (Port Harcourt, Nigeria) or in the African diaspora (specifically in Ottawa, Canada and Miami, Florida, USA).

Measures of Psychosocial Variables

We used a revised 10-item HIV-related stigma scale to capture various components of stigma among Black mothers living with HIV [39]. The 10 items adapted include the following: (1) I have been hurt by how people reacted to learning I have HIV, (2) I have stopped socializing with some people because of their reactions to me having HIV, (3) I have lost friends by telling them I have HIV, (4) I am very careful who I tell that I have HIV, (5) I worry that people who know I have HIV will tell others, (6) I am not as good a person as others because I have HIV, (7) Having HIV makes me unclean, (8) Having HIV makes me a bad person, (9) Most people believe that a person with HIV is disgusting, and (10) Most people with HIV are rejected when others find out. These were categorised into four major components of the HIV-related stigma: personalised stigma (items 1–3), worries about disclosure of status (items 4–5), negative self-image (items 6–8), and sensitivity to public reactions about HIV status (items 9–10) [39]. The original scale used a 5-point Likert type response scheme [39, 40]. We modified responses to ‘yes’ (1 point) or ‘no’ (0 points) to determine presence of the item in the respondent’s life. A maximum stigma score of 10 points was possible for our scoring approach. Participants could also respond ‘I don’t know’ or ‘prefer not to answer’. These particular responses were very few (n = 15, 2.2%) and therefore excluded from the data analyses.

The adapted functional social support (FSS) scale [41] was computed using respondent’s scores on seven key attributes as follows: I have people who care about what happens to me; I have chances to talk to someone I trust about my health; I have chances to talk to someone I trust about challenges I face as a mother living with HIV; I have chances to talk to someone I trust about challenges I face with feeding my baby as a mother living with HIV; I get invited to go out and do things with other people including mothers living with HIV; I get useful advice about things that are important to me as a mother living with HIV; I get help when I am sick in bed. Responses were based on a five-point Likert type scale of much less than I would like = 1, less than I would like = 2, some but would like more = 3, almost as much as I would like = 4, as much as I would like = 5. Hence, maximum score attainable on the scale was 35.

The adapted discrimination scale [42] was computed using responses on the following 10 key attributes: you have been treated with less courtesy than other people; you have been treated with less respect than other people; you have received poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores; people have acted as if you are not smart; people have acted as if they are afraid of you; people have acted as if you are dishonest; people have acted as if they are better than you are; you have been called names or insulted; you have been harassed or threatened; you have been followed around in stores. Responses were based on a five-point Likert type scale of less than once a year = 1, a few times a year = 2, a few times a month = 3, at least once a week = 4, almost every day = 5. Thus, a maximum of score of 50 was attainable on the discrimination scale. Measures of other variables included in the model are specified on results Table 4.

Analytical Strategy

Using the independent samples t test, we compared stigma levels on the full-scale and the four sub-scales between mothers living with HIV in Ottawa and Miami. Then, HIV-related stigma scores on the full-scale and the four sub-scales of the mothers in the North American cities were compared with those in Port Harcourt (Africa). After testing for homogeneity of variances and equality of means in the stigma scores for women in the North American cities, a second level of stigma comparison was carried out. That is, we combined the North American (Miami and Ottawa) samples, obtained mean scores, and compared these with mean scores of Port Harcourt mothers. This analysis explicated the degree of ‘North-South’ difference between scores of overall stigma and the four levels of stigma. In addition, this analysis revealed difference in levels of stigma experienced by migrant versus non-migrant Black women living with HIV.

Effect size for the t-statistics was determined using the Hedges g. Like the Cohen d, the Hedges g for effect size was used to estimate the margin of difference between the two groups being compared. It is calculated as the difference in means between the groups divided by the groups pooled and weighted standard deviation [43]. The Hedges g differs from Cohen d because it employs weighted standard deviations. We chose Hedges g over Cohen d because it accounts for difference in samples sizes and unequal variances between groups which were inherent in our data.

Hierarchical linear modelling (HLM) in SPSS 25 was used to determine predictors of HIV-related stigma in each study site. Prior to the analysis, the data were assessed for missing values. There were no missing values on the outcome variable, and the proportion of missing values in the independent variables are small resulting in a list-wise deletion of only 9.9% of the cases. Given that the missing values in each of the independent variables were uncorrelated with the outcome variable (HIV-related stigma score), a plausibility of missing completely at random (MCAR) or missing at random (MAR) in the data as opposed to missing not at random (MNAR) were assumed for each HLM. Given all these reasons, the missing values in the data became negligible in the HLMs analyses.

In the HLMs, contributory effects of 3 blocks of variables on the stigma rating of mothers living with HIV were determined. In order to control for their effects on stigma, sociodemographic variables were entered into block 1. Sociodemographic variables included marital status, number of children born after testing HIV+, household size, years of formal education, and employment status. Psychosocial variables including functional social support and discrimination were entered into block 2 to establish the level of their joint influence on the model. Finally, sociocultural variables were entered into block 3. Sociocultural variables included adherence to infant feeding guidelines, disclosure of HIV status to family, congruency of cultural beliefs with infant feeding guidelines, and self-rated view that health providers are supportive of infant feeding guidelines.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the sociodemographic characteristics of the Black mothers living with HIV who participated in the study are presented in Table 1. In Ottawa, the majority (n = 57, 66.5%) of mothers living with HIV were either single, separated, divorced, or widowed. In Miami (n = 121, 60.8%) and Port Harcourt (n = 340, 85.2%), most of the mothers were married. In Ottawa and Miami, the women gave birth to fewer [1,2, to 3] children than in Port Harcourt [1,2,3,4, to 5] after testing positive for HIV.

The average duration since HIV diagnosis were (M = 12.7, SD = 6.4) years, (M = 10.9, SD = 7.3) years, and (M = 6.3, SD = 3.5) years in Ottawa, Miami, and Port Harcourt, respectively. Most Black mothers living with HIV in Ottawa (n = 50, 56.8%) had some college or university education, whereas in Miami, the majority (n = 131, 65.8%) had some high school, technical, or vocational education. Similarly, in Port Harcourt, most of the women (n = 250, 63.5%) had high school, technical or vocational education. Most of the women in Ottawa (n = 51, 57.3%) and Port Harcourt (n = 320, 87.9%) were on part-time or full-time employment. In contrast, most of the women in Miami (n = 134, 67.3%) were unemployed and received government insurance.

Tables 2 and 3 show the descriptive and t test statistics for HIV-related stigma scores of mothers from the three sites. The results compare scores on the full stigma scale and those on the sub-stigma scales including personalised stigma, HIV status disclosure-related stigma, negative self-image, and sensitivity to public reactions about HIV status. The average HIV-related stigma score was highest in Miami (M = 5.06, SD = 2.57), with the next highest (M = 4.71, SD = 1.89) observed in Ottawa (Table 2). Relative to the two North American cities, HIV-related stigma is lowest (M = 3.78, SD = 1.62) among mothers living with HIV in Port Harcourt.

Results of the t test in Table 2 show no statistically significant mean difference in HIV-related stigma between mothers living with HIV in Ottawa and those in Miami. Furthermore, the Hedges g of 0.3 (Table 2) indicates a non-visible difference in HIV-related stigma between the two groups. Thus, the mean differences of stigma scores observed in Ottawa (M = 4.71, SD = 1.89) and Miami (M = 5.06, SD = 2.57) can be attributed to chance.

Although means of HIV status disclosure-related stigma scores were not significantly different in the two groups, there were significant (p < 0.05) differences in the means of three of the four stigma sub-scale scores. Personalised stigma (t = − 3.51, df = 288), negative self-image (t = −2.17, df = 211.2), and sensitivity to public reactions about HIV status (t = 3.45, df = 211.8) were significantly different between Ottawa and Miami.

Of all these significant differences, only personalised stigma with Hedges’ g of 0.5 was at least medium-sized or had up to one-half a standard deviation difference between the two groups. This is because decision criteria for Hedges’ g are the same as those of Cohen’s d for effect size. Thus, by Cohen’s criteria, the Hedges’ g of 0.5–0.8 as we observed for personalised stigma would imply a moderate or medium mean difference between groups; Hedges’ g < 0.5 implies a small effect size and g > 0.8 implies a large effect size [43].

Results of the t test presented in Table 3 show a statistically significant (p < 0.05) mean difference in HIV-related stigma between mothers living with HIV in the two North American cities and those in the African city. Mothers living with HIV in Ottawa and Miami (M = 4.95, SD = 2.38) experienced greater levels of HIV-related stigma compared with those residing in Port Harcourt (M = 3.78, SD = 1.62). Effect size analysis showed a Hedges’ g = 0.6, implying a moderate or medium mean difference between stigma in the North American cities and in the African city.

There were significant (p < 0.05) differences in each of the stigma sub-scale scores (Table 3). However, with Hedges’ g = 1.1, only personalised stigma had a large difference between mothers in the North American cities (M = 1.65, SD = 1.28) compared with those in Port Harcourt (M = 0.54, SD = 0.83) at p < 0.05. Hedges’ g of 0.5 (Table 3) indicated a medium-sized difference in the expression of negative self-image between mothers in the North American cities (M = 0.63, SD = 0.83) and those in Port Harcourt (M = 0.27, SD = 0.66) at p < 0.05.

Table 4 presents results of the HLM analysis of predictors of HIV-related stigma among mothers living with HIV in Ottawa, Miami, and Port Harcourt. Overall, the results show that all variables included have statically significant joint effects on HIV-related stigma in each of the cities. These are shown with the final block 3 R-squared values (Ottawa = 0.469, Miami = 0.459, and Port Harcourt = 0.191) that were significant at p < 0.01.

Block 1 (sociodemographic variables) had no significant (p > 0.05) joint and independent effects on HIV-related stigma in each of the three study sites. However, the block contributed 15.1%, 7.7%, and 2.4% to total variation of stigma in Ottawa, Miami, and Port Harcourt, respectively. Psychosocial factors (block 2) significantly (p < 0.05) accounted for 22.3%, 36.3%, and 14.1% of the variation in HIV-related stigma in Ottawa, Miami, and Port Harcourt, respectively. Analyses of the independent effects of block 2 variables (Table 4) show that only discrimination had a significant and increasing effect on HIV-related stigma in each of the three cities. FSS was significantly associated with stigma in Miami and Port Harcourt, but not in Ottawa. High levels of FSS corresponded with low levels of HIV-related stigma in Miami and Port Harcourt.

Like the sociodemographic variables, sociocultural factors (block 3) did not significantly (p > 0.05) account for variation of stigma in the three cities. However, among the independent sociocultural variables, we found that when mothers reported infant feeding practices that were congruent with their national guidelines, they reported significantly (p < 0.05) lower levels of HIV-related stigma in Ottawa. In other words, adherence to national infant feeding guidelines was associated with reduced HIV -related stigma in Ottawa.

Discussion and Conclusions

Overall, the findings suggest that HIV-related stigma was highest in Miami, followed by Ottawa and Port Harcourt. Although the levels of stigma vary more in Miami than Ottawa, there was no significant difference in the stigma experience of women between the two cities. However, levels of HIV-related stigma among women living with HIV in these North American cities were moderately higher than those of mothers living in Port Harcourt. The relatively higher level of stigma in Ottawa and Miami may be because, despite being a public health concern, HIV is still relatively less prevalent in both of these cities when compared with Port Harcourt. Although stigma remains prevalent in countries with high and generalised levels of HIV/AIDS, the problem is decreasing because awareness is improving, especially in the wake of increasing access to antiretroviral therapy [44,45,46]. In addition, the degree of demographic homogeneity is likely to affect the extent to which mothers living with HIV experience stigma in their communities of origin. Port Harcourt, for instance, is predominantly African and mothers living with HIV may be less likely to feel isolated in a context where most people are culturally similar. This might provide protection against stigma. On the contrary, Black mothers living with HIV in Ottawa and Miami live in culturally diverse and heterogeneous societies where social differences are already pronounced, a situation that may exacerbate HIV-related stigma.

In addition, as women in the qualitative component of this study indicated, HIV is more mainstreamed in the African context where HIV is commonly discussed in most media platforms including billboards and television. In contrast, in the North American countries, HIV is a topic mostly discussed by specialized people in AIDS service organizations, and in health and social service facilities. The lack of cultural competence and safety in HIV services is a major healthcare barrier for Black women, especially those requiring HIV/AIDS care [47,48,49]. HIV prevention services in Canada are often not culturally tailored to appropriately address needs of ethno-culturally diverse people [47]. This has implications of HIV programming and policy decisions that affect prevention and intervention strategies. In addition, there may be different interpretations of the study questions and scales in these different cultural contexts, which may impact on the women’s interpretation of stigma.

The findings of the study also showed that FSS and discrimination are major predictors of stigma among Black women living with HIV in Ottawa, Miami, and Port Harcourt. However, these factors do not operate uniformly across the three cities. In respect to FSS, the findings indicated that being able to obtain emotional support when in difficult life situations or being able to get help or advice from friends or family can reduce stigma among mothers living with HIV in Miami and Port Harcourt. This finding is generally consistent with studies that have indicated that, overall, FSS can improve mental and physical health outcomes, including reducing vulnerability to sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV/AIDS [50]. However, this study found that the effect of FSS on HIV-related stigma among mothers living with HIV varies significantly across the cities studied. Its effect was more than two times higher in Miami than Port Harcourt. This means that although FSS can generally shield mothers living with HIV from negative social attitudes in Miami and Port Harcourt, its relative absence (presence) will be more detrimental (beneficial) to the psychosocial functioning of mothers living with HIV in Miami than in Port Harcourt.

This study also demonstrated that discrimination had a significant effect on HIV-related stigma among mothers living with HIV in all three cities. Feeling unfairly treated, disrespected, or treated with discourtesy can fuel internalised stigma among mothers living with HIV. However, the relative importance of discrimination in respect to internalised stigma among mothers living with HIV varies significantly across the three cities. In fact, there appears to be a gradient across these three cities. Internalized HIV stigma is most acute among mothers living with HIV who report discrimination in Ottawa, followed by mothers in Miami, and then their counterparts in Port Harcourt. Mothers living with HIV in Ottawa who experience discrimination report internalised HIV stigma levels almost double the magnitude of their counterparts in Port Harcourt.

The disproportionate effect of discrimination on HIV-related stigma in Ottawa and Miami may be because of the multi-ethnic and multi-cultural social character of these two cities. As such, discrimination operates at multiple levels, which can lead to stigmatisation first because of HIV+ status, and second, by virtue of the fact that Black women in the West are members of a historically oppressed or disadvantaged group. Studies show that Black women living with HIV belong to already marginalised groups of African, Caribbean, and Black people, which leads to overlapping forms of stigma resulting in high internalised HIV stigma scores [51, 52]. Studies have also demonstrated that the impact of HIV-related stigma is especially heavy on Black women living in the West [53, 54].

HIV-related policies should be more tailored to social support programs that links Black women to their unique multi-layered identities thereby reducing stigma and promoting their overall long-term mental and physical health. HIV prevention programs and policies need to examine and address the root causes and social determinants of HIV [48]. This includes ensuring authentic involvement of historically marginalised communities like Black women in the formulation and implementation of policy intervention. In addition, HIV and cultural competence education needs to be integrated into the curriculum of health and social service education of professionals to strengthen the healthcare system to eliminate stigma towards Black women living with HIV. Furthermore, promoting adherence to treatment through better access to medications and functional social support as well as counselling about infant feeding options and guidelines are necessary to reduce HIV-related stigma in this population.

In conclusion, this study examined the magnitude and correlates of HIV-related stigma and found cross-national variations in the level of stigma and relative importance of factors associated with it. Readers should interpret this study’s findings with caution because of the use of cross-sectional data, which prevents us from drawing a definitive causal relationship between HIV-related stigma, functional social support, and discrimination. In addition, readers should interpret the findings with caution, because data were collected from self-reports that are vulnerable to social desirability bias. However, overall, this study represents an important step towards understanding how HIV-related stigma manifests in different national and policy contexts in the North and South. Findings of this study may stimulate qualitative research on contextual factors that account for cross-national variations in the level of and factors associated with HIV-related stigma.

Data Availability

Data analysis activities are currently underway. To request access to study data, please contact JE, the principal investigator for the project.

References

UNAIDS. Reduction of HIV-related stigma and discrimination: guidance note, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Switzerland: Geneva; 2014.

Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Prentice-Hall; 1963.

Turan B, Smith W, Cohen MH, Wilson TE, Adimora AA, Merenstein KD, et al. Mechanisms for the negative effects of internalized HIV-related stigma on antiretroviral therapy adherence in women: the mediating roles of social isolation and depression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(2):198–205.

Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Rice WS, Turan JM. Framing mechanisms linking HIV-related stigma, adherence to treatment, and health outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:863–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303744.

Turan B, Rice WS, Crockett KB, Johnson M, Neilands TB, Ross SN, et al. Longitudinal association between internalized HIV stigma and antiretroviral therapy adherence for women living with HIV: the mediating role of depression. AIDS. 2019;33(3):571–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002071.

Beyeza-Kashesya J, Wanyenze RK, Goggin K, Finocchario-Kessler S, Woldetsadik MA, Mindry D, et al. Stigma gets in my way: factors affecting client-provider communication regarding childbearing among people living with HIV in Uganda. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192902. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192902.

Pantelic M, Sprague L, Stangl AL. It’s not “all in your head”: critical knowledge gaps on internalized HIV stigma and a call for integrating social and structural conceptualizations. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):210–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3704-1.

Yahaya LA, Jimoh AA, Balogun OR. Factors hindering acceptance of HIV/AIDS voluntary counseling and testing(VCT) among youth in Kwara State, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14(3):159–64.

Okareh OT, Akpa OM, Okunlola JO, Okoror TA. Management of conflicts arising from disclosure of HIV status among married women in Southwest Nigeria. Health Care for Women Int. 2015;36(2):149–60.

Okoronkwo I, Okeke U, Chinweuba A, Iheanacho P. Nonadherence factors and sociodemographic characteristics of HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Nigeria. ISRN AIDS. 2013;20(13):1–8.

Lawless S, Kippax S, Crawford J. Dirty, diseased & undeserving: the position of HIV positive women. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(9):1371–7.

De Bruyn M. Women & AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34(3):561–71.

Cohen S, Cullinane J. The domestication of AIDS: stigma, gender, and the body politic in Japan. Med Anthropol. 2007;26(3):255–92.

Paudel V, Baral KP. Women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA), battling stigma, discrimination and denial and the role of support groups as a coping strategy: a review of literature. Reprod Health. 2015;12:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-015-0032-9.

Bezner-Kerr RB, Mkandawire P. Imaginative geographies of gender and HIV/AIDS: moving beyond neoliberalism. GeoJournal. 2012;77(4):459–73.

Kalipeni E, Craddock S, Oppong JR, Ghosh J. HIV and AIDS in Africa: beyond epidemiology: Blackwell Publishing; 2004.

Green L, Ardon C, Catalan J. HIV, childbirth and suicidal behaviour: a review. Hosp Med. 2002;61:311–4.

Heath J, Roadway MR. Psychological needs of women living with HIV. Soc Work Health Care. 1999;29:43–57.

World Health Organization. Guidelines on HIV and infant feeding. 2010. Principles and recommendations for infant feeding in the context of HIV and a summary of evidence.2010. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44345/1/9789241599535_eng.pdf.

Canadian HIVPPGDT, Society of O, Gynecologists of C, Canadian F, Andrology S, HIVATN C, et al. Canadian HIV Pregnancy Planning Guidelines: No. 278, June 2012. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;119(1):89–99.

Loutfy MR, Margolese S, Money DM, Gysler M, Hamilton S, Yudin MH, et al. Canadian HIV pregnancy planning guidelines. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34(6):575–90.

World Health Organization. Rapid advice : use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants, version 2. Revised 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. p. 23.

WHO (2016). WHO Guidelines updates on HIV and Infant feeding. Accessed on January 21, 2020 at: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/hiv-infant-feeding-2016/en/.

Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Sawires SR, Ortiz DJ, et al. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 2):S67–79.

Tariq S, Elford J, Tookey P, Anderson J, Annemiek de Ruiter A, O’Connell R, et al. “It pains me because as a woman you have to breastfeed your baby”: decision-making about infant feeding among African women living with HIV in the UK. Sex Transm Infect. 2016;92(5):331–6.

Oladokun RE, Brown BJ, Osunusi K. Infant-feeding pattern of HIV-positive women in a prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programme. AIDS Care. 2010;22(9):1108–14.

Genberg BL, Hlavka Z, Konda KA, Maman S, Chariyalertsak S, Chingono A, et al. A comparison of HIV/AIDS-related stigma in four countries: negative attitudes and perceived acts of discrimination towards people living with HIV/AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2279–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.005.

Lucero J, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Alegria M, Greene-Moton E, Israel B, et al. Development of a mixed methods investigation of process and outcomes of community-based participatory research. J Mixed Methods Res. 2018;12(1):55–74.

Stanton CR. Crossing methodological borders: decolonizing community-based participatory research. Qual Inq. 2014;20(5):573–83.

Ontario Ministry of Finance. Ontario demographic quarterly: highlights of third quarter 2014. In: Office of Economic Policy LaDAB, editor. Ottawa, Canada: Ontario Ministry of Finance.; 2014.

Remis RS, Merid MF, Palmer RW, Whittingham E, King SM, Danson NS, et al. High uptake of HIV testing in pregnant women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48077.

Federal Ministry of Health FN. In: HIV and AIDS Division F, editor. HIV Integrated Biological and Behavioural Surveillance Survey (IBBSS). Abuja: Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria; 2010.

Okerentugba POUS, Okonko IO. Prevalence of HIV among pregnant women in Rumubiakani, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Public Health Res. 2015;5(2):58–65.

Dept. of Regulatory & Economic Resources. Miami-Dade County Economic & Demographic Profile. Miami: Miami-Dade County; 2014.

Research Section DoPaZ, Miami-Dade County.,. Census 2010 Demographic Profile, Miami-Dade County. In: Zoning DoPa, editor. Miami, FL, USA: Miami-Dade County, Department of Planning and Zoning, Planing Division 2011.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2017; vol. 29. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published November 2018. Accessed [February 18, 2020].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report. Atlanta. Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. p. 2015.

FL Department of Health BoCD, HIV/AIDS Section., . Florida Department of Health: Fact Sheets. Black Fact Sheet. In: FL Department of Health BoCD, HIV/AIDS Section., , editor. Florida Department of Health: Fact Sheets. Tallahassee, FL, USA: Florida Department of Health; 2013.

Wright K, Naar-King S, Lam P, Templin T, Frey. Stigma scale revised: reliability and validity of a brief measure of stigma for HIV+ youth. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(1):96–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.001.

Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10011.

Broadhead WE, Gehlbach S, De Gruy F, Kaplan B. The Duke–UNC functional social support questionnaire: measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care. 1988;26(7):709–23.

Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–51.

Ellis PD. The essential guide to effect sizes: statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results. UK: Cambridge Univeristy Press; 2010. p. 3–24.

Gilbert L, Walker L. “They (ARVs) are my life, without them I’m nothing”—experiences of patients attending a HIV/AIDS clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Health Place. 2009;15(4):1123–9.

Sorsdahl KR, Mall S, Stein DJ, Joska JA. The prevalence and predictors of stigma amongst people living with HIV/AIDS in the Western Province. AIDS Care. 2011;23(6):680–5.

Fido NN, Aman M, Brihnu Z. HIV stigma and associated factors among antiretroviral treatment clients in Jimma town, Southwest Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ). 2016;8:183–93. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S114177.

Flicker S, Larkin J, Smilie-Adjarkwa C, Restoule J-P, Barlow K, Dagnini M, et al. “It’s hard to change something when you don’t know where to start”: unpacking HIV vulnerability with aboriginal youth in Canada. Pimatisiwin. 2008;55(2):175–200.

Gahagan J, Ricci C. HIV/AIDS prevention for women in Canada: a meta-ethnographic synthesis. CTIE: Canadian source for HIV and Hepatitis C Information. 2009. https://www.catie.ca/sites/default/files/HIV%20AIDS%20prevention%20for%20women%20in%20canada.pdf.

Jongbloed K, Pooyak S, Sharma R, Mackie J, Pearce ME, Laliberte N, et al. Experiences of the HIV cascade of care among indigenous peoples: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(4):984–1003.

Mkandawire P, Tenkorang E, Luginaah IN. Orphan status and time to first sex among adolescents in northern Malawi. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):939–50.

Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy MR. HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: a qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11):e1001124.

Loutfy MR, Logie CH, Zhang Y, Blitz SL, Margolese SL, Tharao WE, et al. Gender and ethnicity differences in HIV-related stigma experienced by people living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. PloS One. 2012;7(12):e48168.

Avert: Global information and education on HIV and AIDS. HIV and AIDS in the United States. 2019. https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/western-central-europe-north-america/usa.

Logie C, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy M. Associations between HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, gender discrimination, and depression among HIV-positive African, Caribbean, and Black women in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27:114–22. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2012.0296.

Funding

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Infection and Immunity, Grant No. 144831. The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the Health Sciences and Science Research Ethics Board at the University of Ottawa (certificate #H08–16-27), the Carleton University Research Ethics Board-A (CUREB-A, certificate #106300), the Social and Behavioural Institutional Review Board at Florida International University (certificate #105160), and the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Port Harcourt (certificate #UPH/CEREMAD/REC/04). Additionally, permission was obtained from each of the community partner sites where participants were recruited.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Etowa, J., Hannan, J., Babatunde, S. et al. HIV-Related Stigma Among Black Mothers in Two North American and One African Cities. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 7, 1130–1139 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00736-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00736-4