Abstract

Background

The relationship between frailty and nocturnal voiding is poorly understood.

Aim

To characterize the association between frailty, as defined by a frailty index (FI) based upon the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA) criteria, and nocturia, defined by measures of nocturnal urine production.

Methods

Real-world retrospective analysis of voiding diaries from elderly males with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) at an outpatient urology clinic. Males ≥ 65 years with ≥ 2 nocturnal voids were included. A modified FI was calculated from the LUTS database, which captured 39 variables from the original CSHA FI. Patients were divided into 3 groups by modified FI: low (≤ 0.077) (n = 59), intermediate (> 0.077 and < 0.179) (n = 58), and high (≥ 0.179) (n = 41). Diary parameters were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test and pairwise comparisons with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Bonferroni adjustment.

Results

The high frailty group was characterized by higher nocturnal urine volume (NUV), maximum voided volume (MVV), nocturnal maximum voided volume (NMVV), and nocturnal urine production (NUP). The presence of comorbid diabetes mellitus did not explain this effect.

Conclusion

Elderly males seeking treatment for LUTS with a high frailty burden are disproportionately affected by excess nocturnal urine production. Future research on the mechanistic relationship between urine production and functional impairment is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A growing body of literature has associated nocturia with significant morbidity and mortality. Nocturnal voiding is a cardinal feature of several hypervolemic conditions, and may be the presenting sign of serious systemic cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine, and metabolic diseases [1]. Although the cause-and-effect relationship between nocturia and mortality remains to be established, the multitude of comorbid conditions and their association with nocturia risk factors aligns well with the accumulated deficits model of frailty, which considers frailty as a function of the total burden of health deficits acquired across the aging process [2, 3]. Frailty has been conceptualized and measured using a variety of approaches [4,5,6,7,8], but one of the most widely used is the frailty index (FI), a valid and reliable measure derived from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA) [2,3,4]. The FI captures the presence of current diseases, performance in activities of daily living, and physical signs from the physical examination, and higher levels of the FI are closely correlated with increased morbidity and early mortality [2,3,4].

The pathogenesis of nocturia relies upon a fundamental mismatch between nocturnal urine volume and storage, wherein nocturnal voiding may be driven by excess production, as seen in nocturnal polyuria and global polyuria, and/or reduced bladder capacity (either functional or anatomic) [1]. However, to our knowledge, an association between nocturia and frailty has never been described. Accordingly, we sought to use voiding diary data from elderly men with LUTS at an outpatient urology clinic to characterize the relationship between nocturia and frailty.

Methods

Study design and procedures

This study was a retrospective analysis of 24-h voiding diaries completed from 2008 to 2018 by elderly male veterans who were being treated for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) at a Veterans Affairs outpatient urology clinic.

All patients had established care before being asked to complete a voiding diary. Patients were being actively managed by a urologist in accordance with the best practice framework for the evaluation and treatment of nocturia [9], which involved a thorough medical interview and physical examination, with individualized behavioral modification plans (evening fluid restriction, bladder training exercises, etc.) as a first-line intervention; medications for persistent symptoms; and outlet-reducing surgery for urinary retention refractory to pharmacologic therapy [9].

A voiding diary database for retrospective analysis was compiled with approval from the Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System Institutional Review Board. A waiver of informed consent was granted as voiding diaries are a standard of care in the evaluation and management of LUTS [9]. Patient electronic records were reviewed to determine demographics, medications, genitourinary diagnoses, procedures, and comorbidities.

Patients were included if they were male, age ≥ 65 years, and had completed at least one 24-h voiding diary showing ≥ 2 nocturnal voids during the sleeping period. Only the first diary showing ≥ 2 nocturnal voids was included from patients with more than 1 complete diary. Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of lithium-induced diabetes insipidus because of the pronounced association between lithium-containing drugs and polyuria (n = 4) [10].

Data from voiding diaries were collected in a standard manner (as modified from van Kerrebroeck and colleagues) [11] and analyzed retrospectively (Table 1). Although the FI, as originally described, is comprised of 92 items [2], individual studies often use subsets or smaller numbers of items with which to compute the FI [6]. In our study, the LUTS database included 39 of the 70 possible clinical assessment items (out of the total of 92 items) (see Table 2 for a listing of those included in the current study). As is customary for studies using subsets of items from the original CSHA [5, 6], we calculated the FI on the basis of the proportion of conditions in any given patient relative to the total number of conditions in the item pool. This approach was also used in the original description of the FI [2].

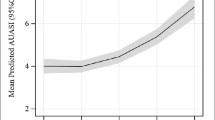

Many studies have employed FI as a categorical variable and defined frailty using FI thresholds, which often differed depending on the population under study [2,3,4, 12]. The distribution of FI scores in our sample differed from the gamma shaped distribution typically reported in those studies and instead clearly represented a biomodal distribution (Fig. 1). In view of this, we divided our sample into groups representing low, intermediate, and high levels of frailty, based on corresponding FI cut points of ≤ 0.077, {> 0.077 and < 0.179}, and ≥ 0.179, respectively.

Statistical analysis

For both patient demographics and diary parameters, categorical variables are reported as frequency (percentage), and continuous variables are reported as median (95% confidence intervals) using Wilcoxon confidence interval estimates. Categorical and continuous variables were compared using the Fisher’s exact test and the Kruskal–Wallis test, respectively. When inter-group differences were found to be significant, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to determine partial order between sample pairs. All tests performed were two-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant, with the Bonferroni correction applied for multiple comparisons.

Results

The frequency distribution of the FI for the patients generating the 158 patient diaries meeting inclusion criteria is shown in Fig. 1. FI cutoffs were {≤ 0.077} for low (n = 59), {> 0.077 and < 0.179} for intermediate (n = 58), and {≥ 0.179} for high (n = 41) for the predefined groups.

A complete overview of patient demographics, comorbid conditions, and urologic treatment history is provided in Table 3. There were no statistically significant differences in demographics, medication usage, or history of surgery or radiation therapy between frailty groups. Among medical comorbidities, diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and congestive heart failure (CHF) were more likely in the high frailty group, with DM occurring in over 25% of the sample overall (44/158).

Table 4 indicates the rates of several measures of nocturnal urine production (NUV, MVV, NMVV, and NUP) in the high frailty group compared to the intermediate and low frailty groups. Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons ([p = 0.05]/3 = 0.017) reached significance for many of these. Additional analysis limited to those cases without DM (n = 114) showed that high frailty continued to be significantly associated with greater nocturnal urine production (NUV, NMVV, NUP; all p < 0.02), but without significant differences in 24-h urine production (p = 0.18).

Discussion

In this group of aged male veterans, higher frailty was associated with greater nocturnal urine production. Although some of this effect might have reflected the disproportionate number of DM patients in the high frailty group (as implied by their higher rate of 24-h urine production, consistent with possible glycosuria), stratification analyses showed that the association between nocturia and frailty persisted independently of DM.

Relationships between frailty and DM in old age are well-acknowledged in the literature [13, 14] and the presence of DM has been shown in several studies to be associated with incident frailty [15, 16] or absence of improvement in frailty status [17]. Although the specific mechanisms of how diabetes may affect frailty remain uncertain, likely candidates may include chronic inflammation and/or the adverse impact of skeletal muscle damage and neuropathic pain on mobility and ambulation [18]. Higher rates of 24-h urine production were also seen in the much smaller number of CHF patients, a group with an increased non-osmotic drive for thirst and high utilization of diuretic agents [19, 20], as well as COPD and OSA, but owing to the relatively low prevalence of these conditions in our sample, we were unable to make any valid statistical inferences about the influence of CHF, COPD, or OSA in this data set.

Although examination of the relationship between nocturia and frailty is novel, frailty has been implicated in other LUTS. Frailty is associated with an increased risk of incontinence [21]. Frail older people, as assessed by an impaired timed up and go test, are also more likely to have overactive bladder (OAB) than age-matched non-frail older people [22]. In addition, among community-dwelling older males, severe symptoms on the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) are associated with a higher prevalence of frailty [23]. In the setting of OAB, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and other LUTS, a reduction in functional bladder capacity is central to the pathogenesis of nocturia in some patients, and conversely, nocturia may be classified as one component of the symptom complex for patients with OAB, BPH with bladder outlet obstruction, or urinary incontinence [1]. However, nocturia is a complex and multifactorial condition, and comorbid LUTS are far from the only underlying etiology.

Unfortunately, older people—and particularly the frail elderly—are often either overtly or covertly excluded from involvement in research studies [24], which has left them underrepresented in pivotal trials on pharmacologic and surgical management for LUTS [25]. Moreover, among older people with LUTS, those with significant frailty may be disproportionately affected by the presence of urologic symptoms as urinary incontinence is associated with an increased risk of hospitalizations, nursing home admissions, and social isolation [26]. Among patients with refractory idiopathic detrusor overactivity, frail older patients experienced a significantly longer duration of recovery and lower long-term success rate following onabotulinumtoxin A treatment compared to their non-frail contemporaries [27]. Among individuals undergoing transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), frailty is associated with an increased occurrence of complications and discharge to a skilled or assisted living facility, which persists after adjusting for factors including age, race, and recent weight loss [28, 29].

The causes and underlying mechanisms of nocturia among frail elderly men and women are multifactorial and, amongst others, include conditions such as peripheral edema, elevated natriuretic peptide secretion (possibly because of sleep apnea), excessive fluid intake, circadian blunting in arginine vasopressin secretion, medications, or renal tubular dysfunction [23, 30, 31]. Desmopressin, which is used in patients with nocturia owing to nocturnal polyuria and no identifiable contributory comorbidities, is not recommended in frail elderly patients due to an increased risk of hyponatremia [32].

This study is subject to a number of limitations. First, our study represents a retrospective single institution cross-sectional analysis based on clinical records. Although a reliable FI which predicts outcomes can be constructed from as few as 20 [33] or even 11 items [34], our frailty model admittedly could not completely duplicate that used in the CSHA. Given the various approaches to characterizing frailty [5], our use of the FI was limited to the specific conditions accessible to us in our patients’ Veterans Affairs records. Specifically, the frailty model used here could not take into account impairment in daily activities or cognitive impairment, which are both important facets of frailty, such that information regarding actual impairment is limited (except for bladder function and cognitive problems). As the FI reflects mainly medical comorbidities, and patients in the high FI group were disproportionately affected by a number of conditions known to cause increased urine production (i.e., DM, COPD, OSA, and CHF), the results of the present study may be a function of comorbidity burden. Although no inter-group differences were observed in the prevalence of comorbid genitourinary diagnoses, the association between frailty and other LUTS such as OAB and urinary urge incontinence may nevertheless pose an operative systematic bias. Given that only elderly male veterans were included in this analysis, results may not be generalizable to all elderly men due to differences in lifestyle and distribution of associated comorbid conditions. Likewise, these results cannot be extrapolated to women. Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, the present analysis is the only study which has applied a validated method of calculating an FI and explored its relationship with nocturia.

Although the predefined cut points allowed for a comparison of voiding diary parameters between 3 groups of approximately equal size, our cutoff for “high frailty” was significantly lower than other meaningful FI cutoffs that have been identified in population studies [3, 4, 35]. These relatively lower values may reflect the fact that our sample consisted of what some have termed a “young-old” group in their late 1960s and early 1970s, unlike the studies of Rockwood et al. [4] and Hoover et al. [35], which included sizeable numbers of persons in their 1980s and above. Future prospective research involving larger well-defined frailty subgroups is needed to further phenotype the etiology of nocturia in frail individuals and establish individualized recommendations for evaluating and managing nocturia in these patients.

Conclusion

A voiding diary analysis of elderly males with nocturia at an outpatient urology clinic identified frailty as a condition significantly associated with increased nocturnal urine production. Future research on the mechanistic relationship between urine production and functional impairment is warranted.

Change history

02 January 2020

In the original publication of the article, the author’s name Jeffrey P. Weiss was misspelled as “Jeffry P. Weiss”.

References

Cornu JN, Abrams P, Chapple CR et al (2012) A contemporary assessment of nocturia: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 62:877–890

Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K (2001) Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. Sci World J 1:323–336

Song X, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K (2010) Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc 58:681–687

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C et al (2005) A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 173:489–495

Dent E, Kowal P, Hoogendijk EO (2016) Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: a review. Eur J Intern Med 31:3–10

Cesari M, Gambassi G, Van Kan GA et al (2014) The frailty phenotype and the frailty index: different instruments for different purposes. Age Aging 43:10–12

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J et al (2001) Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Med Sci 56A:M146–M156

Pritchard JM, Kennedy CC, Karampatos S et al (2017) Measuring frailty in clinical practice: a comparison of physical frailty assessment methods in a geriatric out-patient clinic. BMC Geriatr 17:264

Everaert K, Hervé F, Bosch R et al (2019) International Continence Society consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of nocturia. Neurourol Urodyn 38:478–498

Grünfeld JP, Rossier BC (2009) Lithium nephrotoxicity revisited. Nat Rev Nephrol 5:270–276

van Kerrebroeck P, Abrams P, Chaikin D (2002) The standardisation of terminology in nocturia: report from the Standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 21:167–178

Jones D, Song X, Mitnitski A et al (2005) Evaluation of a frailty index based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment in a population based study of elderly Canadians. Aging Clin Exp Res 17:465–471

Morley JE (2008) Diabetes, sarcopenia, and frailty. Clin Geriatr Med 24:455–469

Sinclair AJ, Abdelhafiz A, Dunning T et al (2018) An international position statement on the management of frailty in diabetes mellitus: summary of recommendations 2017. J Frailty Aging 7:10–20

Bouillon K, Kivimaki M, Hamer M et al (2013) Diabetes risk factors, diabetes risk algorithms, and the prediction of future frailty: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14:851e1–851e6

Chhetri JK, Zheng Z, Xu X et al (2017) The prevalence and incidence of frailty in pre-diabetic and diabetic community-dwelling older population: results from Beijing longitudinal study of aging II (BLSA-II). BMC Geriatr 17:47

Pollack LR, Litwack-Harrison S, Cawthon PM et al (2017) Patterns and predictors of frailty transitions in older men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 65:2473–2479

Zaslavsky O, Walker RL, Crane PK et al (2016) Glucose levels and risk for frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 71:1223–1229

Swedberg K, Cleland J, Dargie H et al (2005) Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure: executive summary (update 2005): The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 26:1115–1140

Waldréus N, Sjöstrand F, Hahn RG (2011) Thirst in the elderly with and without heart failure. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 53:174–178

Park K, Yu M (2016) Frailty and its related factors in vulnerable elderly population by age groups. J Korean Acad Nurs 46:848–857

Suskind AM, Quanstrom K, Zhao S (2017) Overactive bladder is strongly associated with frailty in older individuals. Urology 106:26–31

Jang IY, Lee CK, Jung HW et al (2018) Urologic symptoms and burden of frailty and geriatric conditions in older men: the Aging Study of PyeongChang Rural Area. Clin Interv Aging 13:297–304

Townsley CA, Selby R, Siu LL (2005) Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 23:3112–3124

Suskind AM (2017) Frailty and lower urinary tract symptoms. Curr Urol Rep 18:67

Thom DH, Haan MN, Van Den Eeden SK (1997) Medically recognized urinary incontinence and risks of hospitalization, nursing home admission and mortality. Age Ageing 26:367–374

Liao CH, Kuo HC (2013) Increased risk of large post-void residual urine and decreased long-term success rate after intravesical onabotulinumtoxinA injection for refractory idiopathic detrusor overactivity. J Urol 189:1804–1810

Suskind AM, Walter LC, Jin C et al (2016) Impact of frailty on complications in patients undergoing common urological procedures: a study from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement database. BJU Int 117:836–842

Suskind AM, Jin C, Cooperberg MR et al (2016) Preoperative frailty is associated with discharge to skilled or assisted living facilities after urologic procedures of varying complexity. Urology 97:25–32

van Doorn B, Blanker MH, Kok ET et al (2013) Prevalence, incidence, and resolution of nocturnal polyuria in a longitudinal community-based study in older men: the Krimpen study. Eur Urol 63:542–547

Endeshaw YW, Unruh ML, Kutner M et al (2009) Sleep-disordered breathing and frailty in the Cardiovascular Health Study cohort. Am J Epidemiol 170:193–202

Wagg A, Gibson W, Johnson T 3rd et al (2015) Urinary incontinence in frail elderly persons: report from the 5th International Consultation on Incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 34:398–406

Rockwood K, Mitnitski A (2012) How might deficit accumulation give rise to frailty? J Frailty Aging 1:8–12

George EM, Burke WM, Hou JY et al (2016) Measurement and validation of frailty as a predictor of outcomes in women undergoing major gynaecological surgery. BJOG 123:455–461

Hoover M, Rotermann M, Sanmartin C et al (2013) Validation of an index to estimate the prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling seniors. Health Rep 24:10–17

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Thomas F. Monaghan has no direct or indirect commercial incentive associated with publishing this article and certifies that all conflicts of interest relevant to the subject matter discussed in the manuscript are the following: Adrian S. Wagg has received financial support from Astellas Pharma, Essity Health & Hygiene AB, Ferring, Pierre Fabre and Pfizer Corp outside the submitted work. Dr. Bliwise has served as a consultant for Merck, Jazz, Ferring, Eisai, and Respicardia and speaker for Merck within the last three years, outside the submitted work. Dr. Haddad reports grants from Fonds de dotation Renaitre and from Société Interdisciplinaire Francophone d’UroDynamique et de Pelvi Périnéologie, during the conduct of the study; personal fees and non-financial support from Astellas, personal fees from MedDay Pharmaceuticals and from Novartis Pharma SAS, non-financial support from Dentsply Sirona France, Pierre Fabre Medicament, Allergan France, Bayer HealthCare SAS and Vifor France SA, outside the submitted work. Karel Everaert is a consultant and lecturer for Medtronic and Ferring and reports institutional grants from Allergan, Ferring, Astellas, and Medtronic, outside the submitted work. Jeffrey Weiss is a consultant for Ferring, and the Institute for Bladder and Prostate Research, outside the submitted work. 5 additional authors have nothing to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. A nocturnal voiding database was compiled for retrospective analysis upon approval from the Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent

A waiver of informed consent was granted for retrospective analysis.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: The original publication of the article, the author’s name Jeffrey P. Weiss was misspelled as “Jeffry P. Weiss”.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Monaghan, T.F., Wagg, A.S., Bliwise, D.L. et al. Association between nocturia and frailty among elderly males in a veterans administration population. Aging Clin Exp Res 32, 1993–2000 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-019-01416-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-019-01416-y