Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Methods

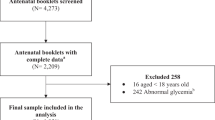

This prospective study was conducted on 256 pregnant women without diabetes referred for prenatal care in the first trimester of pregnancy to two referral University Hospitals (Shariati and Arash Hospitals) during the years 2012 and 2013. Eligible participants were selected consecutively and were followed until delivery and 6 weeks after that. Body weight and fasting plasma glucose were measured in each trimester, and BMI was calculated. Incidence of GDM was recorded, and BMI in this group was compared with those without GDM.

Results

Mean age of women was 28.70 ± 5.57 years and among them, 78 women (30.5 %) developed GDM of which 21 were obese (52.5 %), 25 overweight (27.8 %), and 32 (25.4 %) were normal weight (p = 0.004). Pre-pregnancy obesity (OR 2.74, 95 % CI 1.28–5.88, p = 0.009), family history of diabetes (OR 2.01, 95 % CI 1.13–3.56, p = 0.016), and maternal age more than 30 years (OR 2.20, 95 % CI 1.25–3.88, p = 0.006) were three independent predictors for GDM, and pre-pregnancy obesity was the most potent predictor of GDM.

Conclusion

Women with high BMI and obesity have a significantly higher risk for developing GDM. Pre-pregnancy obesity, family history of diabetes, and age more than 30 years are three independent risk factors for GDM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Impaired glucose tolerance and hyperglycemia first recognized during pregnancy is defined as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) [1]. GDM is the most common metabolic complication of pregnancy that usually improves within few weeks (6–12 weeks) after delivery. Prevalence of GDM varies from one to 14 % in different countries according to the different diagnosis criteria used [2–4].

Women with GDM are at increased risk for developing complications including neonatal hypoglycemia, fetal macrosomia, preeclampsia, and cesarean delivery [5, 6]. Also, the women affected by GDM, have a significantly increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in future [7–9]. In addition to the mothers, children exposed to maternal GDM are at increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes and obesity later in life, too [10–13].

Obesity and diabetes are two important health challenges with rapidly growing prevalence in the world as well as in Iran [14, 15]. The highest burden of diabetes occurs in the developing countries because more than 80 % of diabetes cases live in these countries [16]. The high number of people with diabetes in these countries is due to increase in urbanization and sedentary life style including increased physical inactivity and changes in dietary patterns and increased rate of obesity [17].

Obesity is risk factor for several chronic diseases, including diabetes, heart disease, and some cancers. A recent study in Iran showed that obesity is associated with increased age, low educational levels, being married, living in urban area, and female gender [18]. Also, the most of obesity-attributable deaths are related to ischemic heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus, respectively [19]. The global prevalence of obesity has increased from 6.4 % in 1980 to 12.0 % in 2008 worldwide. Half of this increase occurred between 2000 and 2008 [14]. The prevalence of overweight and obesity together has increased by 27.5 % in adults and 47.1 % in children between 1980 and 2013, and currently, obesity is a major public health challenge in many middle-income countries [15]. The prevalence of obesity in women is higher than in the men in both the developed and developing countries [15]. This high rate of obesity puts obese women at risk for developing obesity-related complications such as diabetes.

The main goal of this study was to investigate the association between maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and obesity with GDM.

Materials and methods

This hospital-based prospective cohort study was conducted on pregnant women in two referral University Hospitals (Dr Shariati and Arash Hospitals) in Tehran, Iran.

Pregnant women who referred for prenatal care in the first trimester of pregnancy to these Hospitals (Dr Shariati and Arash Hospitals) during the years 2012 and 2013 were included in the study consecutively, if they were eligible and consented to participate. Participants were selected by the convenience sampling method, which is a non-probability sampling method, and participants are selected based on their convenient accessibility and proximity to the researcher.

Women with the history of diabetes (type 1 or 2), those referred after the first trimester of pregnancy and those refused to participate were excluded from the study.

Pregnant women were included in the study in the first prenatal visit at first trimester of pregnancy, and they were followed up until delivery. Follow-up of mothers with GDM continued until 6 weeks after delivery. In the first prenatal visit, weight and height were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated and considered as pre-pregnancy BMI. Maternal BMI was categorized as normal: less than 25 kg/m2, overweight: 25–30 kg/m2, and obesity: equal or greater than 30 kg/m2.

Also, fasting blood sugar (FBS) was measured following an overnight fasting. In high-risk women, glucose tolerance test (GTT) was performed at first prenatal visit. Maternal weight was measured at the end of first and second trimester of pregnancy as well as the end of pregnancy. Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) with 75 g glucose was performed in 24th–28th weeks of pregnancy, and diagnosis of gestational diabetes (GDM) was made based on the obtained results according to the ADA 2012 criteria [20]. In order to identify the rate of diabetes development following GDM, 6 weeks after delivery, OGTT was performed again. Gestational weight gain was calculated by subtraction of maternal weight at the end of pregnancy from maternal weigh at first prenatal visit in the first trimester of pregnancy. After finishing the study, based on development of GDM, all participants were divided into two groups of women with GDM (case group) and healthy women without GDM (control group), and different risk factors were compared between the two groups.

The ethics committee at Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol and each participant gave verbal informed consent before enrollment in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [21].

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean and standard deviation for continuous data and number and percentage for categorical data. To compare numerical data between women with and without GDM, independent sample T test was applied and Chi-square test was used for comparison of categorical data. Multiple logistic regression model (MLR) was applied to determine predictors of GDM. In MLR, family history of diabetes, maternal age, gestational weight gain, and obesity were entered to the model. Results of MLR are presented as odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence interval (CI). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn, and area under curve (AUC) was used as an indicator of overall ability of using the BMI before pregnancy to discriminate participants with or without GDM. AUC: 0.5, AUC: 0.5–0.65, and AUC: 0.65–1.0 were interpreted as equal to chance, moderately, highly accurate tests, respectively [22]. SPSS software version 17.00 for Windows was used for data analysis, and a p value equal or less than 0.05 was set as significance level.

Results

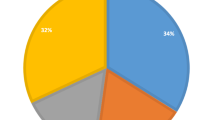

This prospective study was conducted on 256 pregnant women with mean age of 28.70 ± 5.57 years (17–44 years). Among these women, 78 (30.5 %) developed gestational diabetes during pregnancy and 178 (69.5 %) completed pregnancy without GDM. Demographic characteristics of pregnant women with and without GDM have been shown in Table 1.

GDM occurred in 21 obese (52.5 %), 25 overweight (27.8 %), and 32 (25.4 %) normal-weight mothers (p = 0.004). Incidence rate of GDM in overweight women was not significantly different from that in normal-weight women (27.8 vs. 25.4 %, p = 0.75).

There was no significant difference in newborn weight between GDM and healthy groups (p = 0.8) (Table 1). Only five newborns had birth weight of 4000 g or more in our study. Six weeks after delivery, again FBS was measured in GDM group. Ten women lost to follow-up. Among 68 remaining, FBS returned to normal in 53 mothers, was between 100 and 126 mg/dl in 14 women, and remained above 126 mg/dl in one woman.

There was a significant difference in gestational weight gain between the two groups, and gestational weight gain in GDM group was significantly lower than in the healthy group (10.10 ± 7.66 vs. 4.78 ± 6.29 kg, p = 0.03). Although we found a significant association between gestational weight gain and GDM, after adjustment for confounding factors it changed to non-significant.

Results of MLR showed that maternal obesity before pregnancy (BMI ≥30) (OR 2.74, 95 % CI 1.28–5.88, p = 0.009), family history of diabetes (OR 2.01, 95 % CI 1.13–3.56, p = 0.016), and maternal age more than 30 years (OR 2.20, 95 % CI 1.25–3.88, p = 0.006) were three independent risk factors for GDM (Table 2). Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity with odds ratio of 2.74 was the strongest risk factor of GDM. Association of gestational weight gain and GDM was not statistically significant in the MLR.

ROC curve was drawn and showed that maternal BMI before pregnancy was a highly accurate predictor of GDM (AUC = 0.68, 95 % CI 0.61–0.75, p < 0.001) (Fig 1).

Discussion

In the present study, overall GDM incidence was 30.5 % in pregnant women and there was a significant difference in the incidence of GDM between pre-pregnancy obese and normal-weight women. Rate of GDM development in obese women was significantly higher than in the normal-weight women. Pre-pregnancy maternal obesity, family history of diabetes, and age more than 30 years were three independent risk factors of GDM and maternal obesity was the most potent one. However, maternal overweight in our study was not risk factor for GDM.

Risk factors for GDM include high parity, advanced age, family history of diabetes mellitus, nonwhite race, low levels of vitamin D in the first trimester of pregnancy, and overweight and obesity [1, 23]. Vitamin D has skeletal and extraskeletal beneficial effects [24]; vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy has a beneficial effect on metabolic indices and improves glucose metabolism in GDM women [25].

Previous studies have shown that maternal pre-pregnancy dietary pattern is associated with incidence of GDM [26, 27]. In addition, a recent meta-analysis found that there is a significant reverse association between pre-pregnancy and early pregnancy physical activity and the risk of GDM development [28].

Another study revealed that GDM incidence varies in women with different ethnicity [29], and prevalence of GDM in Asian women (3–21 %) is higher than in women in the United States [30]. This study also showed that prevalence of GDM in South Asian countries is higher than in South East (Vietnam, Laous, Taiwan, Filipina, and Malaysia) and East Asian countries (China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan) [29]. The incidence rate of GDM in our study (30.5 %) is higher than in the United States (9.2 %) as well as in India (7.1 %) [4, 31]. However, incidence of GDM in the present study is approximately the same (29.2 %) as reported in a study conducted by similar methodology (hospital-based) in Ahvaz, Iran [4, 32].

GDM and maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and gestational weight gain separately are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, and their combination has additional impact on the pregnancy outcomes [33, 34]. However, diabetes management by dietary modification and insulin treatment significantly reduce the risk for adverse effects including preeclampsia, eclampsia, cesarean delivery, macrosomia, and etc. [34].

In addition, risk of developing metabolic syndrome following pregnancy with GDM increases 2.4-fold compared to normal pregnancy [35]. The risk of development of type 2 diabetes following GDM in pregnancy increases by higher BMI, family history of diabetes, nonwhite ethnicity, and advanced maternal age [9]. However, the risk for future diabetes development can be modified using multimodal postpartum lifestyle interventions [36].

In our study, there was a significant association between pre-pregnancy BMI and GDM. Results showed that maternal pre-pregnancy obesity is an independent predictor of GDM. Previous studies also confirmed this finding [37–39]. Torloni et al., in their meta-analysis, showed that the risk of developing GDM in overweight women was almost twice and in obese women four times more compared to normal-weight women [40]. A study by Singh et al., found that odds ratio for developing GDM for each 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI was 1.08 and for each 5 kg/m2 increase was 1.48 [41]. Also, Roman and their colleges concluded that increasing BMI in women with GDM significantly aggravates maternal and neonatal outcomes [42].

Although we found a significant association between gestational weight gain and GDM, after adjusting for confounding factors it changed to non-significant. In our study, gestational weight gain was lower in GDM group compared to that in the normal pregnancy group. This low gestational weight gain in GDM group may be explained by dietary modification and low calorie intake for better glycemic control. This finding is different from other studies that have indicated excess weight gain in pregnancy as a risk factor for GDM [1]. Previous studies found that maternal obesity, gestational weight gain, and diabetes are independent risk factors for newborn macrosomia [43–45]. In our study, only two newborns had birth weight greater than 4000 g and three newborns had birth weight equal to 4000 g. The mean birth weight of neonates was not significantly different between the two study groups. This may be explained by proper glycemic control in GDM group that reduces the risk of macrosomia. This relation was not assessed in our study because there were a few numbers of neonates with macrosomia (only five newborns) in this study.

Lack of assessment of neonatal outcomes was the main limitation of our study. Another limitation of this study is hospital-based method of the study that caused finding higher incidence rate of GDM in our study.

Future studies with greater sample size and assessment of maternal and fetal outcome are suggested.

Conclusion

Based on the results, women with pre-pregnancy high BMI and obesity are at increased risk for developing GDM.

References

Petry CJ (2010) Gestational diabetes: risk factors and recent advances in its genetics and treatment. Br J Nutr 104:775–787. doi:10.1017/S0007114510001741

Leng J, Shao P, Zhang C et al (2015) Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in Chinese pregnant women: a prospective population-based study in Tianjin, China. PLoS One 10:e0121029. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121029

American Diabetes Association (2009) Standards of medical care in diabetes–2009. Diabetes Care 32(Suppl 1):S13–S61. doi:10.2337/dc09-S013

Rajput RYY, Nanda S, Rajput M (2013) Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus and associated risk factors at a tertiary care hospital in Haryana. Indian J Med Res 137:728–733

Wendland EM, Torloni MR, Falavigna M et al (2012) Gestational diabetes and pregnancy outcomes–a systematic review of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) diagnostic criteria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 12:23. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-23

Wong T, Ross GP, Jalaludin BB, Flack JR (2013) The clinical significance of overt diabetes in pregnancy. Diabet Med 30:468–474. doi:10.1111/dme.12110

Hopmans TE, van Houten C, Kasius A et al (2015) Increased risk of type II diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease after gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 159:A8043

Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D (2009) Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 373:1773–1779. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5

Rayanagoudar G, Hashi AA, Zamora J, Khan KS, Hitman GA, Thangaratinam S (2016) Quantification of the type 2 diabetes risk in women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 95,750 women. Diabetologia 59:1403–1411. doi:10.1007/s00125-016-3927-2

Dabelea D (2007) The predisposition to obesity and diabetes in offspring of diabetic mothers. Diabetes Care 30(Suppl 2):S169–S174. doi:10.2337/dc07-s211

Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Lamichhane AP et al (2008) Association of intrauterine exposure to maternal diabetes and obesity with type 2 diabetes in youth: the SEARCH case-control study. Diabetes Care 31:1422–1426. doi:10.2337/dc07-2417

Reynolds RM, Osmond C, Phillips DI, Godfrey KM (2010) Maternal BMI, parity, and pregnancy weight gain: influences on offspring adiposity in young adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:5365–5369. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0697

Chandler-Laney PC, Bush NC, Rouse DJ, Mancuso MS, Gower BA (2011) Maternal glucose concentration during pregnancy predicts fat and lean mass of prepubertal offspring. Diabetes Care 34:741–745. doi:10.2337/dc10-1503

Stevens GA, Singh GM, Lu Y et al (2012) National, regional, and global trends in adult overweight and obesity prevalences. Popul Health Metr 10:22. doi:10.1186/1478-7954-10-22

Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M et al (2014) Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 384:766–781. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8

Unwin N, Whiting D, Gan D, Jacqmain O, Ghyoot G (eds) (2009) IDF diabetes atlas. International Diabetes Federation, Brussels

Ramachandran A et al (2012) Trends in prevalence of diabetes in Asian countries. World J Diabetes 3(6):110–117

Djalalinia S, Peykari N, Qorbani M, Larijani B, Farzadfar F (2015) Inequality of obesity and socioeconomic factors in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Med J Islam Repub Iran 29:241

Djalalinia S, Moghaddam SS, Peykari N et al (2015) Mortality attributable to excess body mass index in Iran: implementation of the comparative risk assessment methodology. Int J Prev Med 6:107. doi:10.4103/2008-7802.169075

American Diabetes Association (2012) Standards of medical care in diabetes–2012. Diabetes Care 35(Suppl 1):S11–S63. doi:10.2337/dc12-s011

World Medical Association (2013) World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310:2191–2194. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Perkins NJ, Schisterman EF (2006) The inconsistency of “optimal” cutpoints obtained using two criteria based on the receiver operating characteristic curve. Am J Epidemiol 163:670–675. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj063

Lacroix M, Battista MC, Doyon M et al (2014) Lower vitamin D levels at first trimester are associated with higher risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol 51:609–616. doi:10.1007/s00592-014-0564-4

Caprio M, Infante M, Calanchini M, Mammi C, Fabbri A (2016) Vitamin D: not just the bone. Evidence for beneficial pleiotropic extraskeletal effects. Eat Weight Disord. doi:10.1007/s40519-016-0312-6

Yazdchi R, Gargari BP, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Sahhaf F (2016) Effects of vitamin D supplementation on metabolic indices and hs-CRP levels in gestational diabetes mellitus patients: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutr Res Pract 10:328–335. doi:10.4162/nrp.2016.10.3.328

Schoenaker DA, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Callaway LK, Mishra GD (2015) Pre-pregnancy dietary patterns and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: results from an Australian population-based prospective cohort study. Diabetologia 58:2726–2735. doi:10.1007/s00125-015-3742-1

Schoenaker DA, Mishra GD, Callaway LK, Soedamah-Muthu SS (2016) The role of energy, nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns in the development of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of observational studies. Diabetes Care 39(1):16–23. doi:10.2337/dc15-0540

Aune D, Sen A, Henriksen T, Saugstad OD, Tonstad S (2016) Physical activity and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Eur J Epidemiol. doi:10.1007/s10654-016-0176-0

Yuen L, Wong VW (2015) Gestational diabetes mellitus: challenges for different ethnic groups. World J Diabetes 6:1024–1032. doi:10.4239/wjd.v6.i8.1024

Savitz DA, Janevic TM, Engel SM, Kaufman JS, Herring AH (2008) Ethnicity and gestational diabetes in New York City, 1995–2003. BJOG 115:969–978. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01763.x

DeSisto CL, Kim SY, Sharma AJ (2014) Prevalence estimates of gestational diabetes mellitus in the United States, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2007–2010. Prev Chronic Dis 11:E104. doi:10.5888/pcd11.13041532

Shahbazian H, Nouhjah S, Shahbazian N et al (2016) Gestational diabetes mellitus in an Iranian pregnant population using IADPSG criteria: incidence, contributing factors and outcomes. Diabetes Metab Synd. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2016.06.019

Catalano PM, McIntyre HD, Cruickshank JK et al (2012) The hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome study: associations of GDM and obesity with pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care 35:780–786. doi:10.2337/dc11-1790

Abenhaim HA, Kinch RA, Morin L, Benjamin A, Usher R (2007) Effect of prepregnancy body mass index categories on obstetrical and neonatal outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet 275:39–43. doi:10.1007/s00404-006-0219-y

Vilmi-Kerala T, Palomaki O, Vainio M, Uotila J, Palomaki A (2015) The risk of metabolic syndrome after gestational diabetes mellitus—a hospital-based cohort study. Diabetol Metab Syndr 7:43. doi:10.1186/s13098-015-0038-z

Jones EJ, Fraley HE, Mazzawi J (2016) Appreciating recent motherhood and culture: a systematic review of multimodal postpartum lifestyle interventions to reduce diabetes risk in women with prior gestational diabetes. Matern Child Health J. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-2092-z

Kim SK, Saraiva C, Curtis M et al (2013) Fraction of gestational diabetes mellitus attributable to overweight and obesity by race/ethnicity, California, 2007–2009. Am J Public Health 103:e65–e72. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301469

Heude B, Thiebaugeorges O, Goua V et al (2012) Pre-pregnancy body mass index and weight gain during pregnancy: relations with gestational diabetes and hypertension, and birth outcomes. Matern Child Health J 16:355–363. doi:10.1007/s10995-011-0741-9

Cavicchia PPLJ, Adams SA, Steck SE, Hussey JR, Daguisé VG, Hebert JR (2014) Proportion of gestational diabetes mellitus attributable to overweight and obesity among non-hispanic black, non-hispanic white, and hispanic women in South Carolina. Matern Child Health J 18:1919–1926. doi:10.1007/s10995-014-1437-8

Torloni MR, Betran AP, Horta BL et al (2009) Prepregnancy BMI and the risk of gestational diabetes: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Obes Rev 10:194–203. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00541.x

Singh J, Huang CC, Driggers RW et al (2012) The impact of pre-pregnancy body mass index on the risk of gestational diabetes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 25:5–10. doi:10.3109/14767058.2012.626920

Roman AS, Rebarber A, Fox NS et al (2011) The effect of maternal obesity on pregnancy outcomes in women with gestational diabetes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 24:723–727. doi:10.3109/14767058.2010.521871

Alberico S, Montico M, Barresi V et al (2014) The role of gestational diabetes, pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain on the risk of newborn macrosomia: results from a prospective multicentre study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14:23. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-14-23

Olmos PR, Borzone GR, Olmos RI et al (2012) Gestational diabetes and pre-pregnancy overweight: possible factors involved in newborn macrosomia. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 38:208–214. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01681.x

Shi P, Yang W, Yu Q et al (2014) Overweight, gestational weight gain and elevated fasting plasma glucose and their association with macrosomia in Chinese pregnant women. Matern Child Health J 18:10–15. doi:10.1007/s10995-013-1253-6

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pirjani, R., Shirzad, N., Qorbani, M. et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus its association with obesity: a prospective cohort study. Eat Weight Disord 22, 445–450 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0332-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0332-2