Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified (IBDU) is characterized by chronic colitis without specific features of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, and is challenging to diagnose. As consensus guidelines are lacking and published data are limited, treatment recommendations for IBDU in paediatric patients are derived from clinical experience or adopted from strategies used to induce and maintain remission in ulcerative colitis and isolated chronic colitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Chronic disorder of the gastrointestinal tract

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of chronic, relapsing conditions of the gastrointestinal tract [1]. It is typically divided into three subtypes: Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified (IBDU) [1].

Inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified refers to patients with clinical and endoscopic evidence of chronic isolated colitis without specific features of either CD or UC, as defined by the Montreal Working Party in 2005 [2]. Due to previous doubts regarding the exact definition of IBDU and its relative scarcity, patients with IBDU are often excluded from clinical trials [1]. As a result, most studies in patients with IBDU are small and retrospective, and cannot provide definitive treatment conclusions [1].

This article summarizes the epidemiology, diagnosis and management of IBDU in children, as reviewed by D’Arcangelo and Aloi [1].

More common in children than in adults

Although IBDU is the least common IBD subtype in both children and adults, it is twice as common in the paediatric population [1]. In children with IBD, the prevalence of IBDU at diagnosis is 8–30%, although approximately one-third are subsequently reclassified as UC or CD at follow-up. There is a direct correlation between age and frequency of IBDU, which occurs more often in younger age groups. The high frequency of IBDU in children may be explained in part by the atypical phenotype of paediatric IBD and the high rate of isolated colitis in early-onset disease [1].

Diagnosis requires a comprehensive workup

Diagnosis of paediatric IBD can be challenging due to the high frequency of atypical phenotypes (e.g. rectal sparing, caecal patch, backwash ileitis, gastric erosions, etc.) [3]. Distinguishing between UC and CD can be difficult, and the risk of misclassification is high [4]. Clinical signs and symptoms are not useful for the diagnosis of IBDU [1]; instead, a comprehensive diagnostic work-up is required [4].

The work-up for the diagnosis of IBDU should begin with a physical examination, followed by laboratory, nutritional, serological and faecal calprotectin tests, and stool cultures [1]. After excluding other diagnoses, endoscopy and small bowel imaging should be performed [1]. A diagnosis of IBDU is based on the absence of specific findings suggestive of either UC or CD, and should be made when ≥ 1 of the following features (which are not usually seen in UC) are present [4]:

-

Macroscopic and microscopic rectal sparing or transmural inflammation in the absence of severe colitis, with all other features consistent with UC.

-

Significant growth delay (height velocity < 2 standard deviation scores), not explained by other causes.

-

Duodenal or oesophageal ulcers or multiple aphthous ulcerations in the stomach, not explained by other causes (e.g. Helicobacter pylori infection, use of NSAIDs, presence of coeliac disease).

-

Positive anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA) in the presence of negative perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA).

-

Reverse gradient of mucosal inflammation (proximal > distal, except rectal sparing).

Endoscopy and small bowel imaging should be repeated at follow-up, at which time the initial diagnosis of IBDU may be changed to UC or CD in some patients [5].

Treatment can be challenging

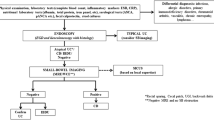

Unlike UC and CD, there are currently no consensus guidelines for the medical management of paediatric IBDU [1]. As a result, the treatment of IBDU can be difficult, with treatment recommendations derived from clinical experience, as well as the strategies used to induce and maintain remission in patients with UC and isolated chronic colitis. Pharmacological treatments for IBDU include 5-aminosalicylic acid (mesalamine), corticosteroids, immunomodulators, biologicals and surgery (Table 1) [1]. Suggested treatment options differ slightly according to disease severity and clinical response (Fig 1), and an individualized approach to treatment is advocated [1].

Pharmacological management of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified, as suggested by D’Arcangelo and Aloi [1]

Inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified has a generally milder disease course, a lower medication burden and lower rates of surgery than UC or CD [1, 6]. In a retrospective, longitudinal study in 797 children and adolescents, paediatric patients with IBDU received fewer corticosteroids and more exclusive enteral nutrition than those with UC, and a lower use of exclusive enteral nutrition and immunomodulators, and higher use of aminosalicylates than those with CD [6].

Take home messages

-

IBDU is relatively common in children due to the atypical phenotype of paediatric IBD and the high rate of isolated colitis in early-onset disease.

-

The diagnosis of IBDU is based on a comprehensive work-up, including physical examination, laboratory testing, serological testing, stool testing and cultures, endoscopy and small bowel imaging.

-

Although IBDU has a generally milder disease course and a lower medication burden than UC or CD, the medical management of IBDU can be difficult, requiring an individualized approach to treatment.

-

Due to the high risk of misclassification, a diagnostic work-up should be repeated at follow-up in order to ascertain the final diagnosis.

References

D’Arcangelo G, Aloi M. Inflammatory bowel disease-unclassified in children: diagnosis and pharmacological management. Paediatr Drugs. 2017;19(2):113–20.

Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, et al. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55(6):749–53.

Levine A, de Bie CI, Turner D, et al. Atypical disease phenotypes in pediatric ulcerative colitis: 5-year analyses of the EUROKIDS Registry. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(2):370–7.

Levine A, Koletzko S, Turner D, et al. ESPGHAN revised Porto criteria for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58(6):795–806.

Winter DA, Karolewska-Bochenek K, Lazowska-Przeorek I, et al. Pediatric IBD-unclassified is less common than previously reported; results of an 8-year audit of the EUROKIDS registry. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(9):2145–53.

Aloi M, Birimberg-Schwartz L, Buderus S, et al. Treatment options and outcomes of pediatric IBDU compared with other IBD subtypes: a retrospective multicenter study from the IBD Porto Group of ESPGHAN. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(6):1378–83.

Manguso F, Bennato R, Lombardi G, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral beclomethasone dipropionate in ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;15(11):e0166455. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0166455.

Willot S, Noble A, Deslandres C. Methotrexate in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: an 8-year retrospective study in a Canadian pediatric IBD center. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(12):2521–6.

Kelsen JR, Grossman AB, Pauly-Hubbard H, et al. Infliximab therapy in pediatric patients 7 years of age and younger. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59(6):758–62.

Gornet JM, Couve S, Hassani Z, et al. Infliximab for refractory ulcerative colitis or indeterminate colitis: an open-label multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;15(18):175–81.

Papadakis KA, Treyzon L, Abreu MT, et al. Infliximab in the treatment of medically refractory indeterminate colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;1(18):741–7.

Caspersen S, Elkjaer M, Riis L, et al. Infliximab for inflammatory bowel disease in Denmark 1999–2005: clinical outcome and follow-up evaluation of malignancy and mortality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(11):1212–7.

Subramanian S, Ekbom A, Rhodes JM. Recent advances in clinical practice: a systematic review of isolated colonic Crohn’s disease: the third IBD? Gut. 2017;66(2):362–81.

Alexander F, Sarigol S, DiFiore J, et al. Fate of the pouch in 151 pediatric patients after ileal pouch anal anastomosis. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(1):78–82.

Dayton MT, Larsen KR, Christiansen DD. Similar functional results and complications after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with indeterminate vs ulcerative colitis. Arch Surg. 2002;137(6):690–4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The article was adapted from Pediatric Drugs 2017;19(2)113–20 [1] by employees of Adis/Springer, who are responsible for the article content and declare no conflict of interests.

Funding

The preparation of this review was not supported by any external funding.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adis Medical Writers. Management of unclassified inflammatory bowel disease in children requires an individualized approach. Drugs Ther Perspect 33, 571–574 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-017-0451-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-017-0451-5