Abstract

Background

Zinc has been used in patients with acne vulgaris for its anti-inflammatory effects; however, it is unclear if zinc supplementation is also beneficial in other inflammatory skin conditions.

Objective

The objective of this article was to determine the effect of zinc supplementation on inflammatory dermatologic conditions.

Data sources

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and Ovid with no time limit up to 29 May, 2019. Trials examining supplementation with zinc in the treatment of inflammatory dermatological conditions (acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, diaper dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, psoriasis, and rosacea) in children and adults were selected.

Results

Of 229 articles, 22 met inclusion criteria. Supplementation with zinc was found to be beneficial in ten of 14 studies evaluating its effects on acne vulgaris, one of two studies on atopic dermatitis, one of one study on diaper dermatitis, and three of three studies evaluating its effects on hidradenitis suppurativa. However, the one article found on psoriasis and the one article found on rosacea showed no significant benefit of zinc treatment on disease outcome.

Conclusions and implications

Some preliminary evidence supports the use of zinc in the treatment of acne vulgaris and hidradenitis suppurativa; however, more research is needed with similar methodologies and larger sample sizes in these diseases. Further, zinc may be of some benefit in the treatment plan for atopic dermatitis and diaper dermatitis; however, additional studies should be conducted to further evaluate these potentially positive associations. To date, no evidence is available to suggest that zinc may be of benefit in rosacea and psoriasis; however, limited data are available evaluating the use of zinc in these conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In this systematic review, of the 22 studies found that met enrollment criteria, 15 showed some degree of improvement in the condition being studied. |

Studies that suggest zinc as an effective treatment are limited to acne vulgaris and hidradenitis suppurativa. |

More studies need to be conducted to better understand the role of zinc therapy in inflammatory dermatologic conditions. |

1 Introduction

Zinc deficiency has become a significant problem throughout the world, and has been linked to many diseases, including skin, neurological, cardiovascular, and renal diseases [1, 2]. It is estimated that zinc deficiency affects about a third of the world’s population, with estimates ranging from 4 to 73% depending on the region, and primarily affects those in developing countries [3]. It is largely related to malnutrition, though diarrheal illnesses can also contribute to zinc deficiency. Although zinc deficiency is uncommon in North America, certain groups are still at risk for inadequate zinc intake [4]. In the USA, zinc intake was found to be inadequate among adults aged 60 years and older, with 35–45% of those surveyed having inadequate zinc intake [5]. Other groups at risk include those from food-insufficient families, those with malabsorptive disorders, and pregnant or breastfeeding women [6].

Zinc deficiency is associated with various dermatological conditions such as pellagra and necrolytic migratory erythema. In addition, zinc deficiency has been reported in several inflammatory skin disease such as atopic dermatitis, lichen planus, and Behcet’s disease [7,8,9]. Inflammatory skin conditions are frequently treated with long-term courses of antibiotics or corticosteroids because of their anti-inflammatory effects [10,11,12]. With a growing desire to reduce the use of corticosteroids and antibiotics, there has been increasing interest in utilizing alternative anti-inflammatory agents. Zinc supplementation has been touted as one alternative for the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases, including acne.

Zinc appears to have several lines of anti-inflammatory action that involve both adaptive and innate immunity and has been shown to decrease neutrophil chemotaxis [13], inhibit T helper-17 cell activity [14], and downregulate the expression of Toll-like receptor-2 from keratinocytes [15]. In this article, we perform a systematic review to methodically compile the existing evidence for the use of zinc for the major inflammatory skin conditions.

2 Methods

2.1 Search Strategy

We systematically searched EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Ovid, and MEDLINE for published clinical studies assessing the use of zinc supplementation in patients with inflammatory skin conditions, including acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis (AD), diaper dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), psoriasis, and rosacea. No limits were placed on the search time frame. The search included all articles published before 29 May, 2019. In the Ovid MEDLINE search, the following search terms were used: zinc, skin diseases, humans, and oral administration. To find relevant studies on the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the following Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms were combined using the ‘AND’ command: zinc and skin disease. For the EMBASE search or relevant studies, the following terms were searched: zinc, skin disease, oral administration, and clinical trial. Additionally, references of the selected articles were searched for additional studies. All searches were filtered to only include human clinical studies and those written in English. No additional studies were found if the “English only” filter was removed.

2.2 Selection of Studies

Five separate reviewers (SD, MN, ARV, MN, and RKS) independently screened all titles and abstracts from the search results. Next, full texts of articles meeting screening criteria were methodically reviewed to determine the suitability of a study. Any incongruities were discussed by the reviewers and resolved. Inclusion criteria included: (1) published in English; (2) clinical trial or clinical study involving the skin; (3) subjects diagnosed with an inflammatory skin disease; and (4) intervention included oral supplemental zinc. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) in vitro and non-human trials and (2) trials not involving the skin.

2.3 Data Extraction

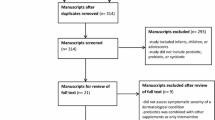

Data extracted from selected studies were documented in a table in the following categories: (1) skin condition; (2) number of subjects; (3) study design (4) zinc intervention and dosage; (3) primary outcome measures; (4) major results; and (5) study limitations. A total of 1667 patients were included in these 22 studies (Fig. 1).

From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(6):e1000097. pmed1000097https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. Overall, 229 records were identified through the database search. After removal of five duplicates, 224 records were screened and 200 did not fit the criteria. Twenty-four full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and two were excluded. 22 studies were included in a qualitative synthesis

2.4 Quality of Included Studies

The reviewers assessed study quality using the 5-point Jadad score for reporting of randomized controlled trials [16]. Methodical assessment of study quality using the Jadad scoring involves evaluation of the system appropriateness and reproducibility of randomization, blinding, and the outcome of subjects. Studies are classified as “high quality” (Jadad score of 3–5) or “low quality” (Jadad score of 0–2).

3 Results

Of the 22 studies, seven used zinc gluconate (10–90 mg/day), 14 used zinc sulfate (0.375–1.8 g/day), and one study used zinc oxide (0.012 g/day). The most common side effect for zinc sulfate and zinc gluconate was gastrointestinal (GI) distress. There were no side effects reported in the zinc oxide study (Table 1).

3.1 Acne

We found that 14 of the total 22 studies assessing the role of zinc involved the treatment of acne. Of the 14 studies conducted, one study used a zinc sulfate/citrate complex, three studies used zinc gluconate, and ten studies used zinc sulfate/sulfate heptahydrate (Table 2).

Of the 14 studies evaluating the use of zinc in acne, nine compared zinc against placebo, three compared zinc against an antibiotic, one compared a constant zinc regimen against a zinc loading dose regimen, and one studied the effect of zinc on those with acne compared to a healthy control group.

In the studies that evaluated zinc compared to placebo, the overall trend was in favor of the zinc group. In Goransson et al. [17] there was a significantly greater reduction in acne in the zinc group and in Hillström et al. [18], both physicians and patients reported significant improvement in the zinc group at 12 weeks. However, in Chan et al. [19], though a significant reduction in comedones and inflammatory lesions was seen in the zinc group, it is difficult to conclude this is the effect of zinc supplementation alone as the active group tested the effect of zinc supplementation in combination with lactoferrin and vitamin E.

When it came to the three studies that compared zinc to antibiotics, there was a greater improvement in the antibiotic groups. In Cunliffe et al. [20], the antibiotic group reported significant subjective improvement in acne compared with the zinc group. In Dreno et al. [21], the zinc group had a 31.2% success rate, compared with 63.4% in the antibiotic group. In Michaëlsson et al. [22], there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of lesion counts, with a 65% reduction in lesion counts in the zinc group compared to a 69% reduction in lesion count for the antibiotic group at 12 weeks.

Meynadier [23] found that treatment with zinc resulted in a significant mean improvement in inflammatory papules and pustules, with no significant difference between the loading dose group and the non-loading dose group. However, the percentage of subjects with “marked improvement” was higher in the loading dose group.

In the three studies that compared zinc compared to three treatment groups (placebo, vitamin A, and zinc/vitamin A), there were varying results. In Michaëlsson et al. [24], there was a significant decrease in the papules, pustules, and infiltrates in the zinc-only group and a significant decrease in comedones in the vitamin A group. However, in this study, zinc plus vitamin A was not better than zinc alone at improving acne. In the study by Vahlquist et al. [25], neither vitamin A alone nor placebo induced any significant change in serum zinc levels. However, in the groups that were treated with zinc or zinc in combination with vitamin A, there was a significant increase in serum zinc levels. In the study by Michaëlsson [26], it was noted that the best response was seen in pustules and infiltrates. The most considerable improvement within 4 weeks was seen in the zinc group and no comparable results were seen in the placebo or vitamin A group.

Last, Rebello et al. [27] studied zinc in healthy individuals and patients with acne, and found that plasma zinc was initially significantly lower in patients with acne than in healthy individuals and increased significantly in both groups after supplementation. There was no significant difference between groups with regard to the level of increase in serum zinc. Sebum excretion rate and sebum free fatty acid content were initially significantly higher in patients with acne and were not reduced in either group with zinc supplementation. Propionibacterium acnes and Propionibacterium avidum lipases showed 80% inhibition at a serum zinc concentration of 2.0 mM/L. Propionibacterium granulosum lipase was inhibited by only 36% at the same concentration.

Common side effects seen over the 14 studies were nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain in those patients treated with zinc. In the three studies comparing zinc against antibiotics, one study [21] noted GI distress (n = 36) and arthralgia/urticaria (n = 1) in the antibiotic group. Of the five studies comparing zinc to placebo only, in one study, the placebo group showed GI distress (n = 5) and fatigue (n = 1) [18]. In Verma et al. [28] and Weimar et al. [29], participants in the placebo group, n = 11 and n = 2, showed worsening of condition. As both studies utilized placebo capsules containing lactose, this may be the cause of acne worsening. In the three studies that examined zinc vs. placebo vs. vitamin A vs. zinc/vitamin A, specifics on adverse events were not given. In Rebello et al. [27], n = 2 of the acne group that received zinc supplementation did not finish the study because of nausea.

3.2 Atopic Dermatitis

Two studies evaluated the effect of oral zinc on AD (Table 3). One study examined the supplementation with the Z-Span capsule vs. placebo while the second compared oral zinc oxide to oral antihistamine. Ewing et al. [30] recruited 50 children between the ages of 1 and 16 years with AD. The study was conducted over 8 weeks in a parallel, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design. Patients were either given either a 1 Z-Span capsule (61.8-mg zinc sulfate capsule) three times daily or one placebo capsule three times daily. Enrolled subjects were allowed to continue their usual regimen of emollients, topical corticosteroids, and trimeprazine. The outcomes measured were degree of redness, daytime itch, night-time sleep disturbances, and eczema severity based on erythema and surface area. The results showed that at 8 weeks, the mean itch score was significantly higher in the zinc group, p = 0.01. There were no significant changes in the other symptom scores. Between the two groups there were no significant differences in severity scores (p = 0.60). Adverse effects included loose stools, exacerbation of AD, itchy maculopapular rash, and one placebo subject developed a herpes simplex skin infection.

In Kim et al. [31], 101 subjects were enrolled. The first part of the study compared baseline hair zinc levels in 58 children between the ages of 2 and 14 years with mild-to-moderate AD (Eczema Area and Severity Index [EASI] score < 26) with 43 sex- and age-matched participants without a dermatological condition and found a significant decrease in average hair zinc levels in patients with AD at baseline, which subsequently increased after oral supplementation. This same change did not occur in the control group. The second part of the study was an 8-week prospective, randomized, evaluator-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel comparative study to determine the effects of oral zinc on AD. Group A was given oral zinc oxide tablets once daily along with oral antihistamines and topical moisturizers. Group B was given oral antihistamines and topical moisturizers only. For both groups, the measured outcomes were as listed: baseline hair zinc levels, hair zinc levels after oral supplementation, EASI, transepidermal water loss, visual analog scale (VAS) for pruritus and sleep disturbances, and side effects. There was an improvement in EASI score in both groups, but group A had a significantly lower EASI score compared with the control at weeks 4 and 8 (p = 0.013 and p = 0.044, respectively). Although there was a decline in transepidermal water loss in both groups at 2, 4, and 8 weeks, the decrease was significant in oral zinc group at 8 weeks compared with the control (p = 0.015). In both groups, there was a decrease in pruritus VAS score; however, the decrease was greater in group A at 8 weeks compared with group B. There was a decrease in sleep disturbance VAS score in both groups with no significant difference between groups. No side effects were reported.

3.3 Diaper Dermatitis

One study compared the effects of oral zinc gluconate supplementation against calcium sulfate and cellulose on diaper dermatitis. Collipp [32] examined 179 newborn infants, with 89 subjects in the treatment group and 90 subjects in the control group. The double-blind, placebo controlled, parallel-group comparative study was performed over 4 months. Ten milligrams of oral zinc gluconate supplements was given to the newborns in the active group starting from the first or second day after birth to 4 months of age. The newborns in the control group were given calcium sulfate 220 mg and cellulose 95 mg. The enrollees were measured for height and weight, incidence of diaper rash, and incidence of oral thrush. It was found that infants who received oral zinc gained more height and weight compared with the control group, and showed a decreased incidence of thrush, but differences were not significant. There was a significant reduction in the incidence of infants with zinc supplementation, as only 13 of the 89 zinc-treated subjects developed a diaper rash compared with 31 of the 90 placebo-treated subjects.

3.4 Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Three studies assessed the impact of oral zinc supplementation in adults with HS: Hessam et al. [33] assessed the effects of oral zinc gluconate combined with topical triclosan, Brocard et al. [34] used oral zinc gluconate alone, and Dreno et al. [35] examined the effects of zinc on inflammatory markers of the skin. Hessam et al. [33] and Brocard et al. [34] did not have a control group in their studies.

Hessam et al. [33] conducted a retrospective chart review of 66 adult patients with HS in Hurley stage I and II who were treated with a combination of zinc gluconate 90 mg/day and topical triclosan 2% twice daily for 3 months and found that there was a significant decrease in disease severity, extent of erythema, and number of inflammatory nodules. There was, however, no significant difference in the number of fistulas or the intensity of pain, assessed with a VAS. The authors concluded that a combination of zinc gluconate and tricosan could be used as anti-inflammatory treatment for patients with HS in Hurley stage I and II. Of note, triclosan has now been banned by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in over-the-counter products [36].

Brocard et al. [34] conducted a prospective study following 22 patients with intractable HS in Hurley stage I, II, and III in which previous treatment with antibiotics, isotretinoin, surgery, or anti-androgens were ineffective. They took oral zinc gluconate 90 mg/day until complete or partial remission was maintained for 4 months, after which, the dose was decreased by 15 mg every 2 months. The average follow-up duration for the 22 patients was 23.7 months. The researchers measured therapeutic response by the number of patients in complete remission, which they defined as the disappearance of lesions or no new lesions for at least 6 months, or partial remission, defined by a reduction of 50% or more of the number of nodules, or a shorter cycle of inflammatory lesion. By the end of the study, 36% of patients experienced complete remission, and 63.6% had a partial remission. In patients with complete remission, a reduction in the dosage to 2–4 capsules/day resulted in relapse of the disease. Increasing the dose prevented relapse. The authors rationalized that this was because treatment with zinc gluconate was suppressive, rather than curative.

Despite these studies showing a positive response to zinc treatment clinically, Dreno et al. [35] found that treatment with zinc gluconate significantly altered the balance of inflammatory markers in lesional HS skin compared with samples obtained before treatment. Comparison of lesional HS skin samples before and after 3 months of treatment with zinc gluconate, 90 mg/day, revealed a significant increase in the expression of all innate immunity markers, except transforming growth factor-β, Toll-like receptor-3, and ß-defensin 2, contradicting previous results indicating that zinc gluconate had anti-inflammatory activity. The reason for their findings are unclear in light of the improvement in HS that was seen with similar dosing, but the authors suggest that the anti- or pro-inflammatory activity seen with zinc gluconate administration is dose dependent [35].

3.5 Psoriasis

One study evaluated the effects of oral zinc sulfate on psoriasis [37] in a 4-month double-blind, cross-over study with 19 healthy outpatients with stable plaque psoriasis, and four inpatients with extensive plaque psoriasis. Alternate patients received oral zinc sulfate 220 mg or sucrose three times daily for 2 months, and were switched to the opposite tablet for an additional 2 months.

Zinc levels from patients with psoriasis were measured in involved and uninvolved skin biopsies, and fasting serum and compared with subjects without psoriasis. They found that lesional psoriatic skin possessed a consistently higher, but statistically insignificant zinc concentration than unaffected skin (before treatment 0.20 > p > 0.10, during treatment 0.10 > p > 0.05, after treatment 0.40 > p > 0.20). They postulated that increased zinc concentration in psoriatic scales corresponded to greater losses of zinc during desquamation, resulting in a low serum zinc seen in patients with psoriasis. Zinc treatment in patients with psoriasis led to an increase in serum zinc to greater than baseline serum zinc levels in control patients. There was also a statistically insignificant increase in zinc levels in skin samples during treatment. Disease improvement, characterized by decreased redness, infiltration, or scaling, a decrease in new lesions, and central clearing of existent lesions, was not found to be different between treatment with zinc and placebo.

3.6 Rosacea

Bamford et al. [38] evaluated the effects of oral zinc sulfate on rosacea. A total of 44 patients completed this randomized double-blind trial, with 22 patients receiving 220 mg of oral zinc sulfate twice daily for 90 days, and the other 22 receiving placebo.

Rosacea severity was assessed using the four primary rosacea features: transient/non-transient erythema, papules, pustules, and telangiectasia. Rosacea severity scores were found to have a statistically insignificant decrease in both groups at 90 days compared with baseline. The zinc group showed a slightly greater, but statistically insignificant, frequency of GI side effects such as nausea, discomfort, constipation, and diarrhea. The authors concluded that treatment with oral zinc sulfate was not associated with a significant improvement in rosacea symptoms. In fact, zinc supplementation was less efficacious than placebo, leading to early termination of their study.

4 Discussion

Zinc supplementation may have an anti-inflammatory effect leading to clinical improvement in some dermatologic conditions, but may not be universally beneficial in dermatologic inflammatory disease. While studies in acne vulgaris and HS show particular promise, the evidence is relatively weak or conflicting, for its role in the treatment of rosacea, psoriasis, diaper dermatitis, and AD.

The physiology behind the potential efficacy of zinc in acne vulgaris and HS is unclear, although may reflect the anti-inflammatory role of zinc in hair follicle-based diseases. Curiously, there was no effect seen in rosacea, which is known to have sebaceous gland dysfunction in some subtypes, although there simply may not be enough data to evaluate potential effects in these particular subtypes [38]. It is unclear if patients with zinc deficiency have a higher likelihood of developing these dermatological diseases as serum zinc levels were not often measured in these studies. With regard to acne, Vahlquist et al., Weismann et al., and Rebello et al. commented on baseline serum zinc level. In Weismann et al., baseline serum zinc was normal in all patients [39]. In Vahlquist et al., the investigators found that the baseline serum zinc levels of patients with acne were similar to those of the healthy controls [25]. In Rebello et al., the baseline serum zinc levels were significantly lower in the acne group compared with the healthy group. However, only in one case was the baseline serum zinc level of a patient with acne below the normal range [27]. Kim et al. found that more patients with AD had a zinc deficiency that was characterized by decreased hair zinc levels, rather than serum levels, suggesting that zinc deficiency may be associated with AD [31]. Further studies are needed to assess the role of zinc deficiency in these common dermatological conditions.

There is some evidence supporting the use of zinc supplementation for HS [33,34,35]. However, sample sizes of the studies were small and most lacked a control and/or placebo group. In Brocard et al. [34], the lack of a control or a designated end-point to the study made it unclear whether the high response rate was maintained, or if patients were lost to follow-up as soon as treatment proved to be ineffective. Additionally, the trial conducted by Hessam et al. [33] used oral zinc gluconate with topical triclosan, making it difficult to identify whether the zinc or triclosan was the reason for higher observed success rates in the treatment group. As there appears to be some benefit to zinc therapy in HS, and there were no adverse effects, larger controlled studies should be performed.

Overall, there were few studies on oral supplementation of zinc for AD, diaper dermatitis, psoriasis, and rosacea. Of the two studies found on AD, the data were conflicting on whether zinc increased or decreased itching [30, 31]. The study conducted by Collipp [32] on diaper dermatitis showed some evidence that zinc may help in the prevention of diaper rash. In the one psoriasis study identified, the authors concluded that although abnormal zinc metabolism could be involved in disease pathology, supplementation with zinc did not improve disease outcome [37]. Last, the study by Bamford et al. [38] on rosacea found zinc to be less effective than placebo, and led to more adverse effects.

Overall, several limitations exist across the zinc-based studies. Many of the acne vulgaris studies used placebos with ingredients, such as lactose, that may worsen acne in the control groups [28, 39]. With the exception of a few studies, the sample size across all inflammatory conditions identified have been small and relatively few studies exist on conditions outside of acne vulgaris. Several studies did show significant results; however, results are not generalizable as methodologies, dosing, and the formulation of zinc varied. It is important to note that different zinc formulations have different amounts of zinc (zinc sulfate [23% zinc], zinc acetate [30% zinc], or zinc gluconate [14% zinc]) [40]. Limited studies have reported similar levels of absorption between zinc gluconate and zinc sulfate, but lower levels of zinc absorption from zinc oxide supplements [41,42,43]. As zinc gluconate has a lower concentration of zinc compared to zinc sulfate, it would require higher doses to obtain the same level of serum zinc, assuming similar absorption. Therefore, to minimize the size of the capsule as well as cost, zinc sulfate may be a better option for future studies or clinical use. Many of these studies also did not compare the efficacy of zinc by dose. Brocard et al. did notice increased flares in HS when the dose was decreased to 30–60 mg of elemental zinc daily, which improved when the dose was increased [34]. However, the other studies do not report an effective dose.

Regarding side effects, several studies reported GI-related side effects, including nausea, cramping, and vomiting. When GI distress is present, the formulation may be switched to zinc picolinate, as this is associated with a decreased level of GI irritation compared to zinc gluconate [44]. However, none of the studies reviewed here utilized zinc piclonate, thus it is unclear if the study findings will extend to zinc piclonate.

Notably, zinc supplementation is known to have a competing effect on copper levels [45]. Zinc competes with copper for metallothionein in the small intestine, blocking copper from being carried to the liver where it would bind with ceruloplasmin. For copper to be absorbed, it would need to be bound to this protein. High levels of circulating ceruloplasmin can help to assess for copper deficiency within tissues [46]. This should be kept in mind as copper deficiency can cause anemia in potential subjects undergoing long-term zinc therapy.

Overall, we do not believe there is sufficient evidence to support the use of zinc supplementation in the treatment of AD, psoriasis, and rosacea. A caveat in assessing those with dermatitis is that acrodermatitis enteropathica may present with an AD-like clinical presentation in some patients and, in the setting of low zinc levels, zinc supplementation should be strongly considered.

Our systematic review demonstrated that there is early but limited research evaluating the effectiveness of zinc supplementation on inflammatory skin disease. More studies evaluating oral supplementation with zinc will help us to better understand its role in the treatment of inflammatory skin disease, the most promising of which at this time appear to be acne and HS. Future studies would also be of benefit to assess if zinc supplementation may reduce the burden of antibiotic exposure in these chronic inflammatory conditions.

5 Conclusions

Some preliminary evidence supports the use of zinc in the treatment of acne vulgaris and HS; however, more research should be conducted with similar methodologies and larger sample sizes in these diseases. More studies need to be performed to further evaluate the effect of zinc on AD, diaper dermatitis, psoriasis, and rosacea.

References

Roohani N, Hurrell R, Kelishadi R, Schulin R. Zinc and its importance for human health: an integrative review. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18(2):144–57.

Jurowski K, Szewczyk B, Nowak G, Piekoszewski W. Biological consequences of zinc deficiency in the pathomechanisms of selected diseases. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2014;19(7):1069–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00775-014-1139-0.

World Health Organization. Chapter 4: Childhood and maternal undernutrition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Institute of Medicine FaNB. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

Ervin RB, Kennedy-Stephenson J. Mineral intakes of elderly adult supplement and non-supplement users in the third national health and nutrition examination survey. J Nutr. 2002;132(11):3422–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/132.11.3422.

Dixon LB, Winkleby MA, Radimer KL. Dietary intakes and serum nutrients differ between adults from food-insufficient and food-sufficient families: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. J Nutr. 2001;131(4):1232–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/131.4.1232.

Gholizadeh N, Mehdipour M, Najafi S, Bahramian A, Garjani S, Khoeini Poorfar H. Evaluation of the serum zinc level in erosive and non-erosive oral lichen planus. J Dent (Shiraz). 2014;15(2):52–6.

David TJ, Wells FE, Sharpe TC, Gibbs AC. Low serum zinc in children with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1984;111(5):597–601. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1984.tb06630.x.

Saglam K, Serce AF, Yilmaz MI, Bulucu F, Aydin A, Akay C, et al. Trace elements and antioxidant enzymes in Behçet’s disease. Rheumatol Int. 2002;22(3):93–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-002-0195-x.

Bhatia ND, Vlahovic TC, Green LG, Martin G, Lin T. Halobetasol 0.01% lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis of the lower extremities. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(10):1029–36.

Latter G, Grice JE, Mohammed Y, Roberts MS, Benson HAE. Targeted topical delivery of retinoids in the management of acne vulgaris: current formulations and novel delivery systems. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11:10. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics11100490.

Xu W, Meng K, Wu H, Miura T, Suzuki S, Chiyotanda M, et al. Vitamin K2 immunosuppressive effect on pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Int. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.14014. [Epub ahead of print].

Dreno B, Trossaert M, Boiteau HL, Litoux P. Zinc salts effects on granulocyte zinc concentration and chemotaxis in acne patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72(4):250–2.

Kitabayashi C, Fukada T, Kanamoto M, Ohashi W, Hojyo S, Atsumi T, et al. Zinc suppresses Th17 development via inhibition of STAT3 activation. Int Immunol. 2010;22(5):375–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxq017.

Jarrousse V, Castex-Rizzi N, Khammari A, Charveron M, Dreno B. Zinc salts inhibit in vitro Toll-like receptor 2 surface expression by keratinocytes. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17(6):492–6. https://doi.org/10.1684/ejd.2007.0263.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12.

Göransson K, Lidén S, Odsell L. Oral zinc in acne vulgaris: a clinical and methodological study. Acta Derm Venereol. 1978;58(5):443–8. https://doi.org/10.2340/0001555558443448.

Hillström L, Pettersson L, Hellbe L, Kjellin A, Leczinsky C, Nordwall C. Comparison of oral treatment with zinc sulphate and placebo in acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1977;97(6):681–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1977.tb14277.x.

Chan H, Chan G, Santos J, Dee K, Co JK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine the efficacy and safety of lactoferrin with vitamin E and zinc as an oral therapy for mild to moderate acne vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(6):686–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.13607.

Cunliffe W, Burke B, Dodman B, Gould D. A double-blind trial of a zinc sulphate/citrate complex and tetracycline in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101(3):321–5.

Dreno B, Moyse D, Alirezai M, Amblard P, Auffret N, Beylot C, et al. Multicenter randomized comparative double-blind controlled clinical trial of the safety and efficacy of zinc gluconate versus minocycline hydrochloride in the treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris. Dermatology. 2001;203(2):135–40.

Michaëlsson G, Juhlin L, Ljunghall K. A double-blind study of the effect of zinc and oxytetracycline in acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1977;97(5):561–6.

Meynadier J. Efficacy and safety study of two zinc gluconate regimens in the treatment of inflammatory acne. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10(4):269–73.

Michaëlsson G, Juhlin L, Vahlquist A. Effects of oral zinc and vitamin A in acne. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113(1):31–6.

Vahlquist A, Michaëlsson G, Juhlin L. Acne treatment with oral zinc and vitamin A: effects on the serum levels of zinc and retinol binding protein (RBP). Acta Derm Venereol. 1978;58(5):437–42.

Michaëlsson G. Oral zinc in acne. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1980;Suppl. 89:87–93.

Rebello T, Atherton DJ, Holden C. The effect of oral zinc administration on sebum free fatty acids in acne vulgaris. Acta Derm Venereol. 1986;66(4):305–10.

Verma K, Saini A, Dhamija S. Oral zinc sulphate therapy in acne vulgaris: a double-blind trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 1980;60(4):337–40.

Weimar V, Puhl S, Smith W, tenBroeke J. Zinc sulfate in acne vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114(12):1776–8.

Ewing C, Gibbs A, Ashcroft C, David T. Failure of oral zinc supplementation in atopic eczema. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1991;45(10):507–10.

Kim J, Yoo S, Jeong M, Ko J, Ro Y. Hair zinc levels and the efficacy of oral zinc supplementation in patients with atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94(5):558–62. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-1772.

Collipp PJ. Effect of oral zinc supplements on diaper rash in normal infants. J Med Assoc Ga. 1989;78(9):621–3.

Hessam S, Sand M, Meier NM, Gambichler T, Scholl L, Bechara FG. Combination of oral zinc gluconate and topical triclosan: an anti-inflammatory treatment modality for initial hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84(2):197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.08.010.

Brocard A, Knol AC, Khammari A, Dreno B. Hidradenitis suppurativa and zinc: a new therapeutic approach: a pilot study. Dermatology. 2007;214(4):325–7. https://doi.org/10.1159/000100883.

Dreno B, Khammari A, Brocard A, Moyse D, Blouin E, Guillet G, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: the role of deficient cutaneous innate immunity. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148(2):182–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2011.315.

Office of the Commissioner. FDA in brief: FDA issues final rule on safety and effectiveness for certain active ingredients in over-the-counter health care antiseptic hand washes and rubs in the medical setting. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/FDAInBrief/ucm589474.htm.

Voorhees J, Chakrabarti S, Botero F, Miedler L, Harrell E. Zinc therapy and distribution in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100(6):669–73.

Bamford JT, Gessert CT, Haller IV, Kruger K, Johnson BP. Randomized, double-blind trial of 220 mg zinc sulfate twice daily in the treatment of rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(4):459–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05353.x.

Weismann K, Wadskov S, Sondergaard J. Oral zinc sulphate therapy for acne vulgaris. Acta Derm Venereol. 1977;57(4):357–60.

Wegmüller R, Tay F, Zeder C, Brnic M, Hurrell RF. Zinc absorption by young adults from supplemental zinc citrate is comparable with that from zinc gluconate and higher than from zinc oxide. J Nutr. 2014;144(2):132–6. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.113.181487.

Henderson LM, Brewer GJ, Dressman JB, Swidan SZ, DuRoss DJ, Adair CH, et al. Effect of intragastric pH on the absorption of oral zinc acetate and zinc oxide in young healthy volunteers. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1995;19(5):393–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607195019005393.

Wolfe SA, Gibson RS, Gadowsky SL, O’Connor DL. Zinc status of a group of pregnant adolescents at 36 weeks gestation living in southern Ontario. J Am Coll Nutr. 1994;13(2):154–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.1994.10718389.

Siepmann M, Spank S, Kluge A, Schappach A, Kirch W. The pharmacokinetics of zinc from zinc gluconate: a comparison with zinc oxide in healthy men. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;43(12):562–5. https://doi.org/10.5414/cpp43562.

Barrie SA, Wright JV, Pizzorno JE, Kutter E, Barron PC. Comparative absorption of zinc picolinate, zinc citrate and zinc gluconate in humans. Agents Actions. 1987;21(1–2):223–8.

Guo CH, Wang CL. Effects of zinc supplementation on plasma copper/zinc ratios, oxidative stress, and immunological status in hemodialysis patients. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10(1):79–89. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.5291.

Cousins RJ. Absorption, transport, and hepatic metabolism of copper and zinc: special reference to metallothionein and ceruloplasmin. Physiol Rev. 1985;65(2):238–309. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1985.65.2.238.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were received for the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

Raja K. Sivamani serves as a scientific advisor and editor to LearnHealth and as a consultant to Burt’s Bees and Dermala. Cindy J. Chambers serves as a consultant to Burt’s Bees. Simran Dhaliwal, Mimi Nguyen, Alexandra R. Vaughn, and Manisha Notay have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dhaliwal, S., Nguyen, M., Vaughn, A.R. et al. Effects of Zinc Supplementation on Inflammatory Skin Diseases: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Evidence. Am J Clin Dermatol 21, 21–39 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-019-00484-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-019-00484-0