Abstract

Purpose

Advancements in management of non-communicable diseases using regular reminders on lifestyle and dietary behaviors have been effectively achieved using mobile phones. This study evaluates the effects of regular communication using a mobile phone on dietary management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) among patients attending Kitui County Referral Hospital (KCRH) in Kenya.

Methods

Pre/post-study design among eligible and consenting T2DM patients visiting KCRH was used for this study. One hundred and thirty-eight T2DM patients were enrolled; 67 in the intervention group (IG) and 71 in the control group (CG). The IG received regular reminders on key dietary practices through their mobile phones for six months while the CG did not. The Net Effect of Intervention (NEI) and bivariate logistic regression were used to determine the impact of mobile phone communication intervention at p < 0.05. SPSS version 24 was used to analyze the data.

Results

The results revealed an increase of respondents who adhered to the meal plan in the IG from 47.8% to 59.7% compared to a decrease from 49.3% to 45.1% in CG with corresponding NEI increasing (16.1%) significantly (p < 0.05). The proportion of respondents with an increased frequency of meals increased from 41.8 to 47.8% in the IG compared to a reduction from 52.1% to 45.1% in the CG with corresponding NEI increasing (13.0%) significantly (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Regular reminders on lifestyle and dietary behaviors using mobile phone communication improved adherence to dietary practices such as meal planning and frequency of meals in the management of T2DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder that is characterized based on the blood glucose level and occurs due to the lack of efficiency in utilizing insulin or lack of production of insulin [1]. The prevalence of diabetes in the world has been increasing in the recent decades [2]. It is estimated that by 2030, the number of cases worldwide will exceed 400 million [3]. The condition result from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both [4]. The most common form of diabetes is Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) accounting for over 90% of diabetes cases [5]. Glycemic control has been the ultimate objective in any diabetes therapy achieved through the interplay of lifestyle and self-management measures such as a change in diet, physical activity and medication adherence [6]. Despite proper control significantly being effective in the reduction of the risks of complications, studies from around the world reveal poor adherence to self-care practices [7, 8].

The extent to which patients follow the recommended dietary regime is suboptimal in most cases, ranging from 22 to 70% [9]. Health care systems in developing countries, Kenya included, have focused so much on communicable diseases like HIV, AIDS and malaria, with limited emphasis on diabetes (DM) [10]. There is relatively a large number (About 200) of T2DM patients that are treated at Kitui County Referral Hospital (KCRH) diabetes clinic in Kenya [11]. KCRH serves members of Kitui County which is largely arid and semi-arid, with a relatively higher T2DM prevalence rate and a lower Human Development Index compared to other counties in Kenya.

The current interventions to manage T2DM in most hospital facilities in Kenya is counselling on diet, physical activity and medication adherence delivered as group health talks. Apparently, these interventions have been seen to have a low impact due to poor adherence to diet, health-seeking behaviour and drugs. Consequently, hyperglycemia and long-term complications, increased morbidity and premature mortality have been observed in most health facilities. It also ultimately increases the cost burden of health care for the condition to the government, communities and individuals [12].

Dietary and lifestyle habits have been shown to improve after the mobile phone intervention in the management of T2DM [13]. In Kenya, the mobile phone penetration has continued to soar from 75.4% reported in 2012 [14] to about 100% in 2018 [15]. Mobile phones are used not just as a basic communication tool but also, for accessing information [16]. The use of this mobile phone communication, therefore, presents an opportunity of targeting health messages to individuals, unlike health talks delivered to groups. It is also easy to monitor the delivery of messages. There is widespread ownership of phones by most patients. However, there is limited information on the effectiveness of their use in the management of T2DM in the Kenyan setting.

Methods

Study site

The study was carried out at Kitui County Referral Hospital (KCRH) a Level Five Hospital in Kitui County, Kenya. The catchment area for KCRH is majorly the entire population of Kitui County.

Study design

The study design used pre-post data that included quantitative component. Using social demographic, the participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (IG) that received frequent and regular mobile phone communication on dietary management of T2DM or the control group that did not receive the communication. Data were collected at baseline and six months after intervention and analyzed to determine the change in relevant variables to determine if the intervention had a significant impact on the dietary management practices. The dependent variables were dietary practices while the independent variable was the use of mobile phone communication (Table 1).

Study population

The study population comprised consenting Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) patients visiting the Out Patient Department (OPD) diabetes clinic, aged 20–70 years diagnosed with T2DM at least one year before this study, and owning mobile phones at the time of enrollment. Key dietary management messages were developed and communicated through the participants’ mobile phones five days a week for six months to the intervention group. The control group did not receive these messages but continued diabetes management through regular visits to the Diabetes Clinic at KCRH.

Sample size determination

From Kitui County Referral Hospital (KCRH) records, 200 Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) patients visited the facility in February 2017 [11]. Using the Krejcie and Morgan formula [17] formula; s = X2NP(1-P) ÷ d2(N-1) + X2P(1-P); where s = required sample size; X2 = the table value of chi-square for 1 degree of freedom at the desired confidence level (3.841 for 95% confidence interval); N = the population size; P = the population proportion (assumed to be 0.50 since this would provide the maximum sample size); and d = the degree of accuracy expressed as a proportion (0.05). Using the formula, 3.841(200) (0.5) (1–0.5)/ (0.05) (0.05) (200–1) + 3.841 (0.05) (1–0.05) = 132 patients. To factor in chances of participants dropping out before the 6 months period lapse, the sample size was adjusted upwards by 10% to cater for attrition [18]. Therefore, 10/100 of 132 = 13.2, giving a total sample size of 132 + 13 = 145 individuals. The patients were randomly assigned to either an intervention (IG) or control group (CG).

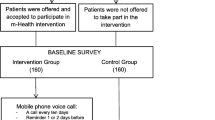

Consecutive sampling technique was used in this study where every eligible and consenting Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) patients that came to the hospital in the month of March and April 2017 were selected and assigned to either the intervention or the control group. This technique is recommended for sampling small finite populations of less than 100,000 [17] as was the case of T2DM patients attending Kitui County Referral Hospital (KCRH) for treatment. In total, 138 patients were sampled in this study; 67 of them in the intervention group and 71 in the control group. Out of the eligible 200 T2DM patients on follow up from the previous one month [11], 138 (67 in the intervention group and 71 in control group) completed the two phases of the study (baseline and after six months) as shown in Fig. 1.

Formulation of the text messages

Short Message Service (SMSs) messages were formulated based on established dietary management recommendations for T2DM [19, 20]. The messages were formulated in English and translated to the predominant local language (the Kamba dialect) in Kitui County. As recommended by Adikusuma et al., 2017 [21] and Haddad et al., 2014 [22], both early morning and afternoon reminders have been reported to have the biggest impact on the dietary and lifestyle management of T2DM patients. The study adopted Ramanchandran et al., 2013 [23] protocol where the messages sent had approximately 160 characters for simplicity to the recipient. Characters refer to individual letters, numbers, and symbols that make up words and sentences. It is recommended that the SMS should not exceed 160 characters as some participants may be challenged technically once the number of characters have been exceeded. The messages were reviewed by Kitui County Referral Hospital (KCRH) physician, nurse and nutritionist for completeness and delivery was between 5.00 and 08.00 am. Patients provided a mobile phone number on which they preferred to receive the regular messages. In addition, the respondents were called on weekends to ascertain that all the SMSs sent within the week had been received and well understood.

Data collection instrument

Longitudinal data collection was used; at month 0 (during enrollment of participants) and at the end of the 6 months. Structured questionnaires were administered using face-to-face to both the IG and CG to collect data on social demographics and dietary habits. The same questionnaire was used for both the baseline and end line survey as recommended by Badedi and others [24]. The questionnaire collected information on the patient’s ability to adhere to recommendations and reminders provided on daily basis by health personnel. In addition, data on the frequency of meals and snacks consumed was assessed by the ability to take three meals and more than three snacks in a day as recommended [25]. Intake of fruits and vegetables was assessed by respondents’ ability to consume 2–4 servings of fruits and 3–5 servings of vegetables daily as recommended by the Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation [19]. A dietary diversity score (DDS) assessment that was based on 10 food groups was used and the cut-off was set at ≥ 5 food groups [26].

Data analysis

Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS software for windows Version 24. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the socio-demographic characteristics with chi square used to assess the randomness in enrollment of participants in the IG and CG. The Net Effect of Intervention (NEI) analysis was used to determine the impact of the intervention at a 95% confidence level [27]. This was achieved by the change ( ±) in percentage obtained from IG compared with the change obtained from the CG. This compared the observed change in dietary practices among patients in the IG to the changes in the CG. The following formula was used:

Where

- NEI:

-

represent Net Effect of Intervention

- Y0:

-

represents proportion (%) within the intervention group at baseline

- Y1:

-

represents proportion (%) within the intervention group after 6 months

- X0:

-

represents proportion (%) within the control group at baseline

- X1:

-

represents proportion (%) within the control group after 6 months

Bivariate logistic regression was conducted to assess the impact of frequent mobile phone- based reminders on the use of meal plan, frequency of meals, frequency of snacks, fruits intake, vegetable intake, and dietary diversity (DDS). The Odds Ratio (OR) in the bivariate logistic regression model was used to bring out the strength of association between intervention and the control groups for each variable, while the Wald test examined the significance for individual regression coefficients in the logistic regression. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

Table 2 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants enrolled in this study. From the results, the majority of the respondents were female (65.7% in the experimental group and 62% in the control group), aged above 40 years (92.5% in the experimental group and 88.7% in the control group) and married (74.6% in the experimental group and 84.5% in the control group). In addition, the highest proportion (38.8% in the experimental group and 38.0% in the control group) were unemployed. From X2, the p-value was greater than 0.05 indicating randomness in distribution of participants into either the IG and CG groups. The insignificant p-values indicate minimal bias caused by the confounding variables.

Dietary practices of the respondents

Table 3 shows that the proportion of respondents who used a meal plan increased from 47.8% to 59.7% in the intervention group and decreased from 49.3% to 45.1% in the control group. The NEI (16.1%) increase was statistically significant (OR = 1.77 (95% CI = 1.09–2.87), p < 0.05). The proportion of respondents whose frequency of meals was at least three meals per day increased from 41.8% to 47.8% in the intervention group and decreased from 52.1% to 45.1% in the control group. The NEI (13%) increase was statistically significant (OR = 1.69 (95% CI = 1.04–2.74), p < 0.05).

The proportion of respondents who increased the frequency of consumption of snacks increased from 20.9% to 32.8% in the intervention group and decreased from 14.1% to 9.9% in the control group. The NEI of (16.1%) increase was statistically significant (OR = 2.04(95% CI = 1.10–3.76), p < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences in the proportion of respondents who consumed the recommended portion of fruits and vegetables and in the proportion of respondents who consumed food from diverse food groups to meet the recommendations for the dietary diversity score (Table 3).

Discussion

A simple meal plan emphasizing guidelines for healthy food choices is effective in producing changes in glycemic control in T2DM patients [28]. This study found that less than 60% in the intervention and the control group followed a meal plan. However, this proportion is higher compared to a study in Saudi Arabia on T2DM where only 19% used a meal plan [24]. A study on adherence to and factors associated with self-care behaviours in T2DM in Ghana also showed that less than one-third followed a healthy eating plan daily [29]. But the proportion is lower compared to a study by Kamuhabwa and Charles [30] where 69% of T2DM patients followed a meal plan.

This study found that mobile phone communication of dietary management practices significantly increased the use of meal plan among the respondents. One of the reasons why respondents were not following the meal plan in this study could be a low formal education levels as a large per cent, 66% in the intervention group and 56% in the control group, did not have post-primary education. Living in rural settings [29] non-availability of fruits and vegetables and the high cost of foods [31] have been identified by other studies as barriers to adhering to a meal plan.

Frequent meals in T2DM patients reduce post-prandial insulin secretion and enhance insulin sensitivity in diabetes patients [32]. It also prevents hypoglycemia [33]. Respondents who adhered to the recommended number of meals in this study were 42% at baseline in the intervention and 52% in the control group. Brown et al. [34] in their study on college students found that only 18% adhered to the correct frequency of meals per day. But other studies have reported a higher frequency of meals than that observed in this study [32, 35]. A study on dietary patterns in Kitui, Bondo and Trans Mara Districts of Kenya found that those meeting the required frequency of meals per day were 73%, 82% and 88% respectively [36] in the population. Hence this study provided further evidence that the use of mobile phone communication significantly increased the frequency of meals among the respondents in this study. A significant increase in the frequency of meals was observed among diabetes patients in the IG group compared to the control group (p < 0.05). This is similar to the observations reported in other studies [37, 38].

The majority of the respondents did not meet the recommended intake of 3 snacks in a day as per American Diabetes Association [25]. Another study on dietary practices found that 1%, 3% and 4% of respondents consumed snacks as recommended in Kitui, Bondo and Trans Mara Districts, respectively [36]. A Saudi Arabia study among T2DM patients found that 23% took the recommended daily snacks [32]. The low frequency of meals and low intake of snacks in this study could be explained by a lack of knowledge on the recommended frequency of meals and snack intake level, and the poor socio-economic status of the respondents [32, 36].

Consumption of vegetables contributes to the intake of some vitamins and antioxidants, and thus combats deficiencies that could arise with diabetes. Vegetables and fruits also improve bowel function, slow rates of glucose and lipid absorption from the small intestine, and lower blood lipids [38, 39].

There was a low fruit intake (< 30% in the intervention and control groups) in this study. The observations are similar to those reported in a study on food security problems among various income groups in Kenya that found low fruit intake (26%) among the respondents [40]. Low consumption of fruits (46%) was also reported in a Sri Lankan population [38]. These observations are in agreement with the National Micro Nutrient Survey report of 1999 which found that only 10% of the respondents in five districts in Kenya consumed fruits [41].

Lower fruit intake levels have been reported in other studies among T2DM patients than the level reported in this study [29, 42]. This study shows that fruit intake in the population is low and mobile phone communication did not have a significant effect on fruit intake among respondents. But other studies have reported a significant increase (p < 0.05) in fruit consumption in the intervention group compared to the control group after mobile phone intervention [34, 43]. Other studies have reported a non-significant increase in fruit intake after mobile phone intervention [44, 45]. The reason for the low fruit intake in this population could be the seasonality of the fruits. Another reason could be a perception that the population has of fruits as being sweet and having high sugar levels [42]. The other factor could be cost, as was reported in another study [46].

This study also noted that there was low vegetable consumption (< 30%) in the intervention and the control groups. Lower proportions of vegetable consumption among T2DM patients have been reported in other studies [32, 47]. However, a higher proportion of vegetable intake, 46%, 67% and 51%, respectively have been reported by other studies [31, 38, 42]. This study found that mobile phone communication did not have a significant effect on vegetable intake among the respondents. But other studies have reported a significant increase in consumption of vegetables after mobile phone communication intervention [43,44,45].

The two periods of data collection (March and April 2017, and November and December 2017) coincided with the rainy seasons, when vegetables are generally easily available. The low intake of vegetables could therefore be attributed to a lack of knowledge and awareness of the importance of vegetable intake. Similar observations have also been made in other studies [31, 32].

The majority of respondents (> 70%) were not within the recommended fruit (2–4) servings and vegetable (3–5) servings as recommended by the Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation [20]. This puts respondents at increased risk of developing complications such as uncontrolled BP (over 50% in the intervention and over 40% in the control group had uncontrolled BP) as reported in another study by [48]. A high diversity of diets, with foods from different food groups, contributes toward meeting nutrient adequacy [49]. Low dietary diversity is particularly a considerable problem among poor populations of the developing world as their diets are predominantly based on a limited number of starchy staples [50]. The same trend was observed in this study, with less than half (49% in the intervention and 48% in the control group) within the recommended dietary diversity score [DDS] at baseline. Lower DDS was observed by Tiew et al. [42] who found that only 35% of respondents were within the recommended DDS levels. Similarly in another study in Laikipia, Kenya, it was reported that only 37% of the respondents were in the medium DDS category (4–5 food groups) [51]. This was also the case in a study in South Africa [49] where it was observed that only 38% of respondents in Limpopo and 40% in Eastern Cape provinces were within the DDS of 4.

However, a higher percentage (79%) of respondents who were within the DDS was reported among diabetic and hypertensive patients in Cote d’Ivoire [52]. The reason for the low DDS for most respondents in this study could be because of the established food consumption practices among the community at the study site where the majority have a staple diet based on cereals and pulses.

Conclusion

The study sought to understand the impact regular reminders on dietary practices on DM management. From the research, it is evident that the use of mobile phone communication was associated with improved adherence to recommended dietary practices with respect to the use of meal plans, and increased frequency of meals. The study recommends further research and development on the use of SMS and other telecommunication modes in communicating health and nutrition messages to patients with T2DM and other lifestyle diseases to help improve dietary management of the condition.

References

Suresh V, Kunnath J, Reddy A. Prospective dietary radical scavengers: Boon inpharmacokinetics, overcome insulin obstruction via signaling cascade for absorption during impediments in metabolic disorder like diabetic mellitus. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-022-01038-8.

Guariguata L, Whiting D, Hambleton I, Beagley J. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;103(2):137–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002.

World Health Organization. Diabetes infographic. Geneva, Switzerland. 2016. Available at https://www.google.com/search?q=diabetes+infographic+by+who+2016+pdf&oq=Diabetes+infographic+by+WHO+2016&aqs=chrome.1.69i57j33i160.11552j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#imgrc=SD2rzGTGDoSIsM.

Ngugi P, Kimuni N, Ngeranwa N, Orinda O, Njagi M, Maina D, et al. Antidiabetic and safety of Lantana Rhodesiensis in Alloxan induced diabetic rats. Dev Drugs. 2015;4(1). https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-6631.1000129.

Animaw W, Seyoum Y. Increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus in a developing country and its related factors. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187670.

Waari G, Mutai J, Gikunju J. Medication adherence and factors associated with poor adherence among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients on follow-up at Kenyatta National Hospital, Kenya. Pan African Med J. 2018;29(82). https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2018.29.82.12639.

Abebe A, Wobie Y, Kebede B, et al. Self-care practice and glycemic control among type 2 diabetes patients on follow up in a developing country: A prospective observational study. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-022-00995-4.

Belay B, Derso T, Sisay M. Dietary practice and associated factors among type 2 diabetic patients having followed up at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2021;20:1103–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-021-00752-z.

Ganiyu A, Mabuza L, Malete N, Govender I, Ogunbanjo G. Non-adherence to diet and exercise recommendations amongst patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus attending Extension II Clinic in Botswana. Afr J Primary Health Care Fam Med. 2013;5(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v5i1.457.

Mwavua S, Ndungu E, Mutai K, Joshi M. A comparative study of the quality of care and glycemic control among ambulatory type 2 diabetes mellitus clients, at a tertiary referral hospital and a regional hospital in Central Kenya. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9(12). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1826-0.

Mungai J. Face to face interview with Kitui County Referral Hospital physician held on 28th November 2016. 2016. Kitui County.

Oyando R, Njoroge M, Nguhiu P, Sigilai A, Kirui F, Mbui J, et al. Patient costs of diabetes mellitus care in public health care facilities in Kenya. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2019;35(2):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2905.

Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32(1):56–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxq004.

Communications Authority of Kenya. First Quarter Sector Statistics Report for the Financial Year 2015/2016 (Vol. 2016). (2016). Retrieved from https://www.ca.go.ke/images/downloads/STATISTICS/Sector Statistics Report Q1 2015–16.pdf.

Tanui C. Kenya’s Mobile Phone Penetration Surpasses 100% Mark. The Kenyan Wall Street (Kenya). (2018). Retrieved from https://kenyanwallstreet.com/kenyas-mobile-phone-penetration-surpasses-100-mark/.

GSMA. Sub-Saharan Africa mobile observatory 2012. (2012). Retrieved from https://www.gsma.com/publicpolicy/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/SSA_FullReport_v6.1_clean.pdf.

Krejcie R, Morgan D. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas. 1970;38(30):607–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308.

Jones K, Lekhak N, Kaewluang N. Using mobile phones and short message service to deliver self-management interventions for chronic conditions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2014;11(2):81–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12030.

Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation. National clinical guidelines for management of diabetes mellitus. Nairobi, Kenya. 2010. Available at https://www.worlddiabetesfoundation.org/sites/default/files/WDF09-436 National Clinical Guidelines for Management of Diabetes Melitus - Complete.pdf.

Ministry of Medical Services. Clinical nutrition and dietetics reference manual. Nairobi, Kenya. 2010. Available at https://www.coursehero.com/file/26907698/Clinical-Nutrition-Manual-2009-adoc/.

Adikusuma W, Qiyaam N. The effect of education through short message service (SMS) messages on diabetic patients adherence. Scientia Pharmaceutica. 2017;85(23). https://doi.org/10.3390/scipharm85020023.

Haddad N, Istepanian R, Philip N, Khazaal F, Hamdan T, Pickles T, et al. A feasibility study of mobile phone text messaging to support education and management of type 2 diabetes in Iraq. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2014;16(7):455–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2013.0272.

Ramanchandran A, Snehalatha C, Ram J, Selvam S, Simon M, Nanditha A, et al. Effectiveness of mobile phone messaging in prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle modification in men in India. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1(3):191–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70067-6.

Badedi M, Solan Y, Darraj H, Sabai A, Mahfouz M, Alamodi S, Alsabaani A. Factors associated with long-term control of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2109542.

American Diabetes Association. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(1):S61–78. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-S011.

FAO. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/wa_workshop/docs/FAO-guidelines-dietary-diversity2011.pdf.

Oyo-Ita A, Hanlon P, Nwankwo O, Bosch-Capblanch X, Arikpo D, Esu E, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of an intervention project engaging traditional and religious leaders to improve uptake of childhood immunization in Southern Nigeria. PloS One. 2021;16(9): e0257277. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257277.

Yannakoulia M. Eating behavior among type 2 diabetic patients: A poorly recognized aspect in a poorly controlled disease. Rev Diabet Stud. 2006;3(1):11–6. https://doi.org/10.1900/rds.2006.3.11.

Mogre V, Abanga Z, Tzelepis F, Johnson N, Paul C. Adherence to and factors associated with self-care behaviours in type 2 diabetes patients in Ghana. BMC Endocrine Disord. 2017;17(20). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-017-0169-3.

Kamuhabwa R, Charles E. Predictors of poor glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients attending public hospitals in Dar es Salaam. Drug Healthcare Patient Saf. 2014;6:155–65. https://doi.org/10.2147/DHPS.S68786.

Worku A, Abebe S, Wassie M. Dietary practice and associated factors among type 2 diabetic patients. Springer Open J. 2015;4(15). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0785-1.

Mohamed B, Almajwal A, Saeed A, Bani A. Dietary practices among patients with type 2 diabetes in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Food Agric Environ. 2013;11(2):110–114. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253340651.

Meyer C. The development of recommendations for the implementation of nutrition therapy for coloured women with type 2 diabetes attending CHCs in the Cape Metropole (University of Cape Town, South Africa). 2009. Retrieved from https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11427/3267/thesis_hsf_2009_meyer_cm.pdf?sequence=1.

Brown O, O’Connor L, Savaiano D. Mobile MyPlate: A pilot study using text messaging to provide nutrition education and promote better dietary choices in college students. Am Coll Health. 2014;62(5):320–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2014.899233.

Chacko M, Begum K. Dietary practices among type 2 diabetic patients. Int J Health Sci Res. 2016;6(4):370–377. Google Scholar

Hansen A, Christensen D, Larsson M, Eis J, Christensen T, Friis H, et al. Dietary patterns, food and macronutrient intakes among adults in three ethnic groups in rural Kenya. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(9):1671–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980010003782.

Tamban C, Isip-Tan I, Jimeno C. Use of Short Message Services (SMS) for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. ASEAN Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2013; 28(2): 143–149. https://www.asean-endocrinejournal.org/index.php/JAFES/article/view/68.

Senadheera S, Ekanayake S, Wanigatunge C. Dietary habits of type 2 diabetes patients: Variety and frequency of food intake. Nutr Metab. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7987395.

Eswaran S, Muir J, Chey W. Fiber and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):718–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.63.

Olielo T. Food security problems in various income groups of Kenya. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2013;13(4). Retrieved from https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajfand/article/view/94584.

GOK/UNICEF. National Micronutrient Survey report: Anemia and status of iron, vitamin A and zinc in Kenya. 1999. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56424f6ce4b0552eb7fdc4e8/t/57491e882eeb81625aeed64b/1464409865033/Kenya_Micronutrient+Survey_1999.pdf.

Tiew K, Chan Y, Lye M, Loke S. Factors associated with dietary diversity score among individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32(4):665–676. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc4438697/.

Elbert S, Dijkstra A, Oenema A. A mobile phone app intervention targeting fruit and vegetable consumption. Med Internet Res. 2016;18(6). https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5056.

Spring B, Pellegrini C, McFadden H, Pfammatter A, Stump T, Siddique J, et al. Multicomponent mHealth intervention for large, sustained change in multiple diet and activity risk behaviors. Med Internet Res. 2018;20(6). https://doi.org/10.2196/10528.

Partridge S, McGeechan K, Hebden L, Balestracci K, Wong A, Denney-Wilson E, et al. Effectiveness of a mHealth lifestyle program with telephone support (TXT2BFiT) to prevent unhealthy weight gain in young adults. Med Internet Res. 2015;3(2). https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.4530.

Msambichaka B, Eze I, Abdul R, Abdulla S, Klatser P, Tanner M, et al. Insufficient fruit and vegetable intake in a low- and middle-income setting. Nutrients. 2018;10(222). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10020222.

Jayawardena R, Byrne N, Soares M, Katulanda P, Hills A. Food consumption of Sri Lankan adults. Public Health Nutr. 2012;16(4):653–658. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/314.

Theuri A, Makokha A, Kyallo F. Effect of using mobile phone communication on morbidity and health seeking behavior of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients at Kitui County Referral Hospital, Kenya. Int J Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;4(3):83–89. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijde.20190403.13.

Labadarios D, Steyn N, Nel J. How diverse is the diet of adult South Africans? Nutr J. 2011;10(33). Retrieved from http://www.nutritionj.com/content/10/1/33.

Ngala S, Souverein O, Tembo M, Mwangi A, Kok F, Brouwer I. Evaluation of dietary diversity scores to assess nutrient adequacy among rural Kenyan women. 2015. ISBN 978–94–6257–423–6.

Kiboi W, Kimiywe J, Chege P. Determinants of dietary diversity among pregnant women in Laikipia County, Kenya. BMC Nutr. 2017;3(12). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-017-0126-6.

Déré K, Djohan Y, Koffi K, Manhan K, Niamké A, Tiahou G. Individual dietary diversity score for diabetic and hypertensive patients in Cote d’Ivoire. Int J Nutr. 2016;2(1):38–47. CC-license. https://doi.org/10.14302/issn.2379-7835.ijn-16-943.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the technical assistance provided by the medical superintendent, the clinical nutritionist, and nurses at Kitui County Referral Hospital (KCRH). The authors are also immensely thankful to all the patients who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical approval of this study was obtained from the Kenyatta National Hospital/the University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee (KNH-UON ERC) Permit No. KNH/ERC/R/66. Permission to carry out the study was also granted by the Kitui County Referral Hospital management and National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI), Permit No. NACOSTI/P/17/69901/16738. Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from the respondents.

Competing interests

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Theuri, A.W., Makokha, A., Kyallo, F. et al. Effect of using mobile phone communication on dietary management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus patients in Kenya. J Diabetes Metab Disord 22, 367–374 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-022-01153-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-022-01153-6