Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this updated systematic review and meta-analysis was the association between hyperglycemia and periodontitis.

Methods

We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Scopus until March 2021. The key search words were based on "periodontitis" and "hyperglycemia." We included cohort, case–control, and cross-sectional studies, restricted to publications in English. The quality assessment of included studies and data extraction were done by two independent reviewers. Meta-analysis was performed for cross-sectional studies using the random-effects model.

Results

The literature search yielded 340 studies, and finally, 19 and 11 studies were included in systematic review and meta-analysis, respectively. The total sample size of the eligible studies in the meta-analysis was 38,896 participants, of whom 33% were male with a mean age of 51.20 ± 14.0 years. According to a random-effect meta-analysis in cross-sectional studies, the pooled odds ratio (OR) for the association between hyperglycemia and periodontal indices was statistically significant (OR: 1.50, 95%CI: 1.11, 1.90). There was evidence of publication bias (coefficient: − 3.53, p-value = 0.014) which, after imputing missing studies, the pooled OR of the association between hyperglycemia and periodontitis change to 1.55 (95%CI: 1.20, 1.90).

Conclusion

Results of the present study show that hyperglycemia was positively associated with periodontitis. However, more cohort and prospective longitudinal studies should be conducted to find the exact association. Overall, it seems the management of hyperglycemia could be considered as a preventive strategy for periodontitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammatory disease that can accumulate during a lifetime. There is an increased prevalence of periodontitis in the aging population as they keep their teeth [1, 2]. In 2010, 10.8% (743 million) people worldwide were affected by severe periodontitis, with the maximum prevalence at the age of 40 [3]. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2009–2014 reported a higher prevalence of periodontitis among dentate US adults with the age of 30–79 years than previous studies. Also, it was established that 42.2% of dentate US individuals older than 30 years had some category of periodontitis, including 7.9% with severe periodontitis and 34.4% with non-severe periodontitis [2]. Periodontitis is also the sixth major complication of diabetes [4]. It is generally accepted that the cause of most chronic diseases such as diabetes and metabolic syndrome is a pro-inflammatory state derived from excessive calorie intake, over nutrition, and chronic inflammatory dysfunctions [5]. This pro-inflammatory state leads to an increase in inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and oxidative stress, which causes impairment in several crucial biological mechanisms [6]. It seems that hyperglycemia has the most common relationship to periodontal disease. The chronic hyperglycemia state resulting in increased oxidative stress in the periodontium, and it causes elevated levels of inflammatory mediators. These mediators finally lead to the destruction of the crestal alveolar bone and cause periodontitis [7, 8]. Due to the prevalence of periodontitis and the importance of monitoring, this study aims to collect and summarize all evidence of the association between hyperglycemia and periodontitis based on clinical periodontal examinations.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were done according to the PRISMA guideline [9]. To assess the association between hyperglycemia with periodontitis, we conducted a systematic review in all related studies which were searched from comprehensive international databases of PubMed and NLM Gateway (for MEDLINE), Web of Science, and Scopus up to March 2021.

Search strategy

The main bases for the development of search strategies were extracted from “periodontitis” or “hyperglycemia,” and all related terms were included according to this main strategy. The databases were searched by two reviewers independently (Supplementary 1).

Eligibility criteria and selection study

All observational studies (cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort) that investigated the association between hyperglycemia with periodontitis were considered eligible. Studies that were conducted on non-human-subjects, those with duplicate citations, and the non-generalized studies that were limited to sub-group populations were excluded. In the case of multiple publications from the same study, the study with the most comprehensive sample size was included.

After removing duplicate studies, two independent reviewers examined titles and abstracts as well as full texts for relevance. Disagreement between these reviewers was resolved by a third reviewer.

The data was extracted through a checklist which included the following items; information of study; demographic and bibliographic characteristics; methodological information; definition of hyperglycemia and periodontitis, and results of each study.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale by study design (cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort study) [10]. Two reviewers independently evaluated quality assessment and any disagreement resolved by a third reviewer.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed for studies that reported odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) as a measure of the association between hyperglycemia and periodontitis. Due to the small number of cohort and case–control studies in the healthy population, meta-analysis was performed only in cross-sectional studies. Chi-square-based Q test and I-square statistics were used to assess the heterogeneity among studies. I-squared values, 0%, 25%, and 75% showed low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. If heterogeneity were statistically significant (P-value < 0.1) [11], the random-effect meta-analysis model was used (using the Der-Simonian and Laird method) to find the association between hyperglycemia and periodontitis. Subgroup analyses were done with quality assessment, hyperglycemia definition (fasting blood sugar (FBS) and Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c)), and dental indices (periodontal disease (PD), and clinical attachment loss (CAL)). Publication bias was estimated by Egger’s test and the result of this test was considered to be statistically significant at P < 0.1. Publication bias was presented schematically using a funnel plot. When potential publication bias existed, the trim and fill correction method was used to impute missing studies and correct publication bias. Sensitivity analysis was performed to identify the effectiveness of exclusion of each study on the pooled effect size. We undertook a meta-regression analysis to detect the source of heterogeneity. All analyses were conducted using Stata 11 (version 11; StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Search strategy

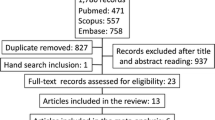

The literature search yielded 340 studies, and after the screening, 19 and 11 studies were included in systematic review and meta-analysis, respectively. Figure 1 summarizes the screening process of the studies. No studies were added during the examination references list of relevant studies.

Qualitative synthesis

The main characteristics of included studies and their quality score are shown in Table 1. Of 19 studies that met the eligibility criteria in the systematic review, 11 were cross-sectional study, 4 case–control, and 2 cohorts which one study reported beta coefficient and one other had not eligible dental indices.

The total sample size of the eligible studies in the systematic review was 41,300, of whom 25% of participants were male with a mean age of 50.0 ± 13.0 years. The total sample size of the eligible studies in the meta-analysis was 38,896 participants, of whom 33% were male with a mean age of 51.20 ± 14.0 years. Periodontal indices and hyperglycemia were measured by using different methods. By type of Community Periodontal Index (CPI), four studies [12,13,14,15] used CPI ≥ 3 mm, and two studies used CPI ≥ 4 mm [16, 17]. By type of CAL periodontal index, 4 studies used CAL ≥ 3 mm [12,13,14,15], 3 used CAL ≥ 4 mm [18,19,20], one studies used CAL ≥ 5 mm [21] and 5 studies used CAL ≥ 6 mm [18, 19, 21,22,23]. By type of PD periodontal index, 6 studies used PD ≥ 4 mm [14, 17, 18, 20, 23, 24], 4 used PD ≥ 5 mm [19, 21,22,23], 2 studies used PD ≥ 2 mm [25, 26], and 1 study PD ≥ 6 mm [24]. Also, by type of hyperglycemia based on HbA1c, 4 studies used HbA1c ≥ 6% [22, 23, 27, 28], one study used HbA1c ≥ 7.5% [29] and one study used HbA1c ≥ 8% [26]. By type of hyperglycemia based on high FBS, 6 studies used FBS ≥ 110 mg/d [12,13,14, 18, 25, 30] and one studies used FBS ≥ 126 mg/dl [19]. The studies were published between 2001 and 2017 years, and most were conducted in Asian countries. Sixteen studies reported adjusted OR at least for two confounders; the most commonly confounding factors were age, gender and smoking status. In 2 cohort studies, effect measure were ranged between 0.86 (95%CI: 0.36–2.06) and 1.88 (95%CI: 0.86- 4.10). In 4 case–control studies, OR and confidence interval was ranged between 1.76 (1.03–3.00) and 4.20 (2.41–7.30).

Quality assessment

The results of the qualitative assessment showed that 15 studies had a high quality, and the remains had a moderate quality. Also, no low-quality studies were observed. The quality scores ranged from 6 to 9.

Quantitative synthesis

The results of the meta-analyses on the association between hyperglycemia and periodontitis according to quality assessment, hyperglycemia, assessed periodontal indices, and hyperglycemia-periodontal indices in cross-sectional studies are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2. Significant heterogeneity was observed among the included studies (I-squared = 84.1%, P < 0.001). There was a significant association between hyperglycemia and periodontal indices (OR: 1.50; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.90). By type of periodontal index, hyperglycemia has a significant association with PD (OR: 1.66; 95% CI: 1.06, 2.26) but not with CAL (OR: 1.07; 95% CI: 0.53, 1.61) and PD/CAL (OR: 1.19; 95% CI: 0.92, 1.45).

According to hyperglycemia definition, we don't found any significant association between FBS with PD (OR: 1.62; 95% CI: 0.95, 2.28), CAL (OR: 1.07; 95% CI: 0.53, 1.61), and PD/CAL (OR: 1.18; 95% CI: 0.86, 1.50). There was also a significant association between HbA1c and PD (OR: 1.87; 95% CI: 1.39, 2.37). By quality assessment, studies with high quality had a significant association (OR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.87) than those with moderate quality (OR: 1.85; 95% CI: 0.68, 3.00).

Publication bias

There was evidence of publication bias (coefficient = -3.53, p-value = 0.014) (Fig. 3). Trim-and-fill analysis indicated that if missing studies are included in the analysis, the pooled OR of the association between hyperglycemia and periodontitis change from 1.50 (95%CI: 1.11, 1.90) to 1.55 (95%CI: 1.20, 1.90).

Meta-regression

Based on the results of the meta-regression analysis, none of the covariates, including sample size, quality score, hyperglycemia definition, and dental indices affect the observed heterogeneity (p-value > 0.10).

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis result was demonstrated that the pooled results were robust, and excluding each study couldn't be affected on the pooled estimate.

Discussion

In the present systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to assess the association between hyperglycemia and periodontitis indices. To the best of our knowledge, up to now, it is the first comprehensive systematic review run on this topic. All observational studies included in this systematic review revealed the associations between high levels of plasma glucose and periodontitis. Based on findings, hyperglycemia was associated with periodontitis. This association was significant regardless of the type of indicators, and definition of diabetes.

Considering the increasing trends of diabetes, MetS, and other metabolic risk factors, attention to the role of these potential risk factors in the incidence or progression of other comorbidities has become an interesting field of research [8, 31]. In this regard, there is some evidence on the association between hyperglycemia and periodontal diseases. This assumption explains that increased levels of plasma glucose could be a risk factor for periodontitis [32]. Our results are consistent with the previous evidence; that reveals a potential association between hyperglycemia and periodontitis [8, 16, 31,32,33]. Previous study revealed that regarding the chronic immune system activation in patients with diabetes, leukocytes and pro-inflammatory markers may be increased [34]. Moreover, the advanced glycated end products (AGEs) as a consequence of hyperglycemia, can increase the inflammatory processes which induce apoptosis [35]. The chronically increased level of plasma glucose and inflammation could be increasing oxidative stress in the periodontium that could lead to elevated levels of inflammatory mediators. Following these procedures destruction of the crestal alveolar bone lead to periodontitis [8, 16, 36].

The methodological quality of included papers was moderate and high. In cross-sectional studies, the sample size was mostly representative of the general population. The exposure was assessed through a defined standard measurement tool. In case–control studies, the same procedures for setting the case and controls were conducted, and exposure was evaluated through the secure data. The criteria for the detection of periodontitis is the critical determinant. The clinical assessment is the gold-standard method of detection of periodontitis progression [31]. The variation of findings may be rooted in different methodological and practical approaches in the selection of periodontal indices, sampling frames, and technical procedures of detection [37, 38].

Scientific experiments have shown that the promotion of general health and detection and treatment of many risk factors such as high plasma glucose could increase oral health and decrease oral diseases [31, 39]. Some of them even emphasized the bidirectional association between diabetes and inflammatory periodontal disease [40]. Considering the discussed results, as a practical implication of research; increasing the awareness about the importance of the control of plasma glucose and management of diabetes must be added to health programs to reduce adverse health outcomes of many oral diseases [31, 39].

Compare with the parallel studies, the present study benefited from many estrangements. It is the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis on the association of hyperglycemia and periodontitis which all available data were searched from international databases. We revealed the gaps of evidence in this field for future complementary researches.

There is some limitation in this study that should be considered. First, it is a secondary study and the quality and representativeness of our data were dependent on the accuracy of the data extracted from the primary studies. Second, according to the cross-sectional nature, it is difficult to establish whether PD causes hyperglycemia or hyperglycemia favors the incidence of PD. Third, because there were few case–control and cohort studies and heterogeneity of presented results, we could not analyze the sub-groups of sex, age, ethnicity, and other practical specifications. Forth, the adjustments of confounders were different in included primary studies; therefore, many other factors, such as the type of treatment and medication or supplement intakes that could influence the association between hyperglycemia and PD, have not been adjusted. Fifth, many potential co-factors of such as oral health, smoking, alcohol consumption, job description, and socio-economic class were not controlled.

Conclusion

The practical findings of the present study suggest an association between hyperglycemia and periodontitis. Thus, prevention and control of hyperglycemia could be considered as a preventive strategy for periodontitis. This approach also could be a helpful method in usual tactic protocols in patients with periodontitis.

References

Slots J. Periodontitis: facts, fallacies and the future. Periodontology 2000. 2017;75(1):7–23.

Eke PI, Borgnakke WS, Genco RJ. Recent epidemiologic trends in periodontitis in the USA. Periodontology 2000. 2020;82(1):257–67.

Frencken JE, et al. Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis–a comprehensive review. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44:S94–105.

Löe H. Periodontal disease. The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(1):329–34.

Bullon P, et al. Metabolic syndrome and periodontitis: is oxidative stress a common link? J Dent Res. 2009;88:503–18.

Dandona P, Aljada A, Bandyopadhyay A. Inflammation: the link between insulin resistance, obesity and diabetes. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:4–7.

Deshpande K, et al. Diabetes and periodontitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2010;14:207.

Wu Y-Y, Xiao E, Graves DT. Diabetes mellitus related bone metabolism and periodontal disease. I J Oral Sci. 2015;7:63–72.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–41.

Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–5.

Higgins JPT, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Kushiyama M, Shimazaki Y, Yamashita Y. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease in Japanese adults. J Periodontol. 2009;80(10):1610–5.

Morita T, et al. Association between periodontal disease and metabolic syndrome. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69(4):248–53.

Morita T, et al. A cohort study on the association between periodontal disease and the development of metabolic syndrome. J Periodontol. 2010;81(4):512–9.

Kwon YE, et al. The relationship between periodontitis and metabolic syndrome among a Korean nationally representative sample of adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:781–6.

Katz J. Elevated blood glucose levels in patients with severe periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28(7):710–2.

Chuang S-F, et al. Oral and dental manifestations in diabetic and nondiabetic uremic patients receiving hemodialysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2005;99(6):689–95.

D’Aiuto F, et al. Association of the metabolic syndrome with severe periodontitis in a large US population-based survey. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;93(10):3989–94.

Benguigui C, et al. Metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and periodontitis: a cross-sectional study in a middle-aged French population. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37(7):601–8.

Thanakun S, et al. Association of untreated metabolic syndrome with moderate to severe periodontitis in Thai population. J Periodontol. 2014;85(11):1502–14.

LaMonte MJ, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease measures in postmenopausal women: the Buffalo OsteoPerio study. J Periodontol. 2014;85(11):1489–501.

Minagawa K, et al. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and periodontitis in 80-year-old Japanese subjects. J Periodontal Res. 2015;50(2):173–9.

Teeuw WJ, et al. Periodontitis as a possible early sign of diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open Diab Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000326.

Timonen P, et al. Metabolic syndrome, periodontal infection, and dental caries. J Dent Res. 2010;89(10):1068–73.

Shimazaki Y, et al. Relationship of metabolic syndrome to periodontal disease in Japanese women: the Hisayama Study. J Dent Res. 2007;86(3):271–5.

Chen L, et al. Association of periodontal parameters with metabolic level and systemic inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Periodontol. 2010;81(3):364–71.

Susanto H, et al. Periodontal inflamed surface area and C-reactive protein as predictors of HbA1c: a study in Indonesia. Clin Oral Invest. 2012;16(4):1237–42.

Iwasaki M, et al. Longitudinal relationship between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease among Japanese adults aged≥ 70 years: the Niigata Study. J Periodontol. 2015;86(4):491–8.

Tanwir F, Tariq A. Effect of glycemic conrol on periodontal status. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2012;22(6):371–4.

Khader Y, et al. Periodontal status of patients with metabolic syndrome compared to those without metabolic syndrome. J Periodontol. 2008;79(11):2048–53.

Rocchietta I, Nisand D. A review assessing the quality of reporting of risk factor research in implant dentistry using smoking, diabetes and periodontitis and implant loss as an outcome: critical aspects in design and outcome assessment. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:114–21.

Nascimento GG, et al. Does diabetes increase the risk of periodontitis? A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of longitudinal prospective studies. Acta Diabetol. 2018;55(7):653–67.

Mealey BL, Oates TW. Diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2006;77(8):1289–303.

Corbella S, et al. Effect of periodontal treatment on glycemic control of patients with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Invest. 2013;4(5):502–9.

Graves DT, et al. Diabetes-enhanced inflammation and apoptosis–impact on periodontal pathology. J Dent Res. 2006;85(1):15–21.

Pradhan S, Goel K. Interrelationship between diabetes and periodontitis: a review. JNMA. 2011;51(183):144–53.

Hardo PG, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and dental care. Gut. 1995;37(1):44–6.

Zarić S, et al. Periodontal therapy improves gastric Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Dent Res. 2009;88(10):946–50.

Bascones-Martinez A, Gonzalez-Febles J, Sanz-Esporrin J. Diabetes and periodontal disease. Review of the literature. Am J Dent. 2014;27(2):63–7.

Stanko P, Holla LI. Bidirectional association between diabetes mellitus and inflammatory periodontal disease. A review. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158(1):35–8.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by Elite Researcher Grant Committee under award number [971188] from the National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD), Tehran, Iran.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM: contributed to the conception, design, interpretation, did a search strategy, analyzed data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript; SD: contributed to the conception, investigated quality assessment of studies, and drafted the manuscript. ES: contributed to the conception, extracted, and extracted and analyzed data; ED: contributed to the conception, assessed the studies, and critically revised the manuscript; JH: contributed to the conception, assessed the studies, investigated quality assessment; AM-G: contributed to the conception, assessed the studies, and investigated quality assessment; RH, contributed to the conception, assessed the studies, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript; MQ, contributed to conception, design, interpretation, assessed and investigated studies, extracted data, drafted the manuscript critically, and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

The protocol study and the proposal approved by the ethical committee of Alborz University of Medical Sciences. All of the included studies would be cited in all reports and all future publications.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mirzaei, A., Shahrestanaki, E., Daneshzad, E. et al. Association of hyperglycaemia and periodontitis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Metab Disord 20, 1327–1336 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-021-00861-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-021-00861-9