Abstract

Purpose

We studied the impact of age on survival and functional recovery in brain-injured patients.

Methods

We performed an observational cohort study of all consecutive adult patients with brain injury admitted to ICU in 8 years. To estimate the optimal cut-off point of the age associated with unfavorable outcomes (mRS 3–6), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were used. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify prognostic factors for unfavorable outcomes.

Results

We included 619 brain-injured patients. We identified 60 years as the cut-off point at which the probability of unfavorable outcomes increases. Patients ≥ 60 years had higher severity scores at ICU admission, longer duration of mechanical ventilation, longer ICU and hospital stays, and higher mortality. Factors identified as associated with unfavorable outcomes (mRS 3–6) were an advanced age (≥ 60 years) [Odds ratio (OR) 4.59, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.73–7.74, p < 0.001], a low GCS score (≤ 8 points) [OR 3.72, 95% CI 1.95–7.08, p < 0.001], the development of intracranial hypertension [OR 5.52, 95% CI 2.70–11.28, p < 0.001], and intracerebral hemorrhage as the cause of neurologic disease [OR 3.87, 95% CI 2.34–6.42, p < 0.001].

Conclusion

Mortality and unfavorable functional outcomes in critically ill brain-injured patients were associated with older age (≥ 60 years), higher clinical severity (determined by a lower GCS score at admission and the development of intracranial hypertension), and an intracerebral hemorrhage as the cause of neurologic disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neurological syndromes due to structural brain lesions (hemorrhage, stroke, and trauma) often result in the necessity of ICU admission and mechanical ventilation initiation [1]. Brain injury patients have longer mechanical ventilation duration and higher mortality than non-neurologic patients [2], and only show a limited capacity of complete recovery. But studies providing information on acute phase parameters that may significantly impact survival or functional outcomes are still scarce. While some authors stated that outcomes of brain-injured patients are primarily driven by the severity of the underlying neurologic pathology, the effect of age on functional recovery is less certain. The mean age of neurologic patients is increasing with the aging of the population, and some studies have found that older patients have high in-hospital mortality and poor functional recovery at acute care discharge due to a lower physiological reserve [3,4,5,6,7,8], while others not [9, 10].

Given the fact that more elderly patients will require acute care as the population ages, and neurologic disease remains one of the main reasons for requiring admission to the ICU and initiation of mechanical ventilation [1], a more detailed understanding of these patient populations may facilitate care and management decisions. This study aimed to examine the effect of age on outcomes and analyze factors associated with unfavorable outcomes in unselected consecutive adult patients with structural brain injury admitted to the ICU.

Methods

Patients and setting

We performed a prospective observational cohort study of all consecutive adult patients with brain injury (intracerebral hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and ischemic stroke) admitted to our 18-bed medical-surgical ICU from November 2012 to November 2020. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement guidelines for observational cohort studies [11]. The protocol was approved by the research ethics board of each participating institution (Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica del Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Spain with approval number A08/17) and the need for informed consent was obtained according to local rules.

Data collection and outcome analysis

Demographic and clinical variables were obtained from the medical records. We collected the following information: age and sex; nature of the primary structural brain lesion [intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), traumatic brain injury (TBI), and ischemic stroke (IS)]; severity at admission estimated by the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)]; development of intracranial hypertension, defined as a sustained elevation (more than 5 min and not related to external stimuli) in intracranial pressure of more than 20 mmHg during the ICU stay; need and duration of mechanical ventilation; length of stay in the intensive care unit and the hospital; in-hospital mortality and discharge status; cause of death in patients who died during hospitalization (brain death, treatment withdrawal, or other causes); functional outcome at hospital discharge after brain injury assessed by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). Functional outcome was defined as good (mRS 0 to 2; independent) or poor (mRS 3 to 6; dependent or dead). Patients were followed-up until hospital discharge.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of the data was assessed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous and categorical variables are expressed as mean and SD, as median and range, or as percentage, as appropriate. Proportions between two groups were compared using the χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate.

To estimate the optimal cut-off point of the age associated with unfavorable outcomes (mRS 3–6), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were used.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify prognostic factors for unfavorable outcomes (mRS 3–6) in neurological patients. Covariates considered for the multivariable analyses included age, etiology of neurologic disease, modified Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (without neurologic and age components to avoid introducing confounding factors, since these are variables that would be repeated in the analysis), Glasgow Coma Scale on admission, and development of intracranial hypertension. All variables included in the multivariate models were tested for colinearity. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used to assess the goodness of fit of the model. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for statistically significant variables. Differences at the level of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 21.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

We have studied a cohort of 619 neurologic critically ill patients for a period of 8 years. Baseline characteristics and main outcomes of patients with neurologic disease and ICU admission are shown in Table 1.

Age and outcomes in patients with brain injury

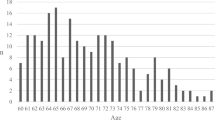

We identified the age of 60 years as the cut-off point at which the probability of unfavorable outcomes after acute brain damage increases, as shown in the ROC curve analysis (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Comparison in baseline characteristics between the two age groups is listed in Table 3. Regarding the distribution by intracranial structural pathologies, there were more patients older than 60 years with intracranial hemorrhage [52% versus (vs) 37%, p < 0.001] or ischemic stroke (6% vs 2.5%, p = 0.031), while the percentage of patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage was higher under 60 years (11% versus 27%, p < 0.001). Patients older than 60 years also had higher severity scores on the SAPS II mean (standard deviation, SD), 41 (15) vs 29.5 (15), p < 0.001] and on the GCS score [mean (SD), 10 (4) vs 11 (5), p = 0.011] than patients younger than 60 years, although there was no difference in the development of intracranial hypertension. There was also no difference in the calculated modified SAPS II, after eliminating the score for the age and GCS components.

Patients older than 60 years had longer duration of mechanical ventilation [median (interquartile range, IR, 8 (3–15.5) vs 7 (2–14), p < 0.001], higher mortality (33% vs 17%, p < 0.001) and longer ICU [median [median (IR), 7 (3–16) vs 5 (2–14) days] and hospital stays [median (IR), 16 (7–30) vs 11 (7–27) days] than patients younger than 60 years. Patients older than 60 years had also worse functional outcomes. The percentage of patients with unfavorable scoring on the modified Rankin scale (mRS) was higher in this group (mRS 3–6, 45% vs 27%, p < 0.001), and also the number of patients in whom a withdrawal of therapeutic measures was performed (16% vs 4%, p < 0.001). Comparison in evolution between the two age groups is shown in Table 3. Functional outcomes and mortality of neurological patients in the two age groups are represented in Fig. 2.

Factors associated with unfavorable outcomes (mRS 3–6) in patients with brain injury

The factors identified as related to an increased unfavorable outcomes (mRS 3–6) in a logistic regression analysis were: an advanced age (≥ 60 years) [OR 4.59, 95% CI 2.73–7.74, p < 0.001], a low score on the Glasgow scale (≤ 8 points) [OR 3.72, 95% CI 1.95–7.08, p < 0.001], the development of intracranial hypertension [OR 5.52, 95% CI 2.70–11.28, p < 0.001], and intracerebral hemorrhage as the cause of neurologic disease [OR 3.87, 95% CI 2.34–6.42, p < 0.001] (Table 4).

Discussion

The main findings of the present study were: (1) Patients over 60 years with brain injury requiring admission to the ICU had higher mortality and worse functional outcomes than patients under 60 years; (2) Patients over 60 years with brain injury requiring admission to the ICU had also a higher duration of mechanical ventilation, and longer ICU and hospital length of stay; (3) Factors identified as associated with unfavorable outcomes (mRS 3–6) in brain-injured patients were an advanced age (≥ 60 years), a low score on the Glasgow scale (≤ 8 points) on admission, the development of intracranial hypertension, and an intracerebral hemorrhage as the etiology of neurologic disease.

The mean age of ICU patients in Europe has been increasing last years in parallel with the age of the general population, and advanced age is associated with increased mortality in intensive care unit patients [12]. Several previous studies have also found that advanced age is a risk factor for higher unfavorable outcomes in the specific neurologic critical care population [3,4,5,6,7,8, 13]. However, other authors found no difference in functional outcome at discharge between young and elderly patients with traumatic brain injury [9, 10], and they argue that the elderly have a slower rate of recovery, but will ultimately achieve a similar long-term functional outcome. In the present study, we have identified the cut-off point above 60 years of age as being associated with worse outcomes. Interestingly, this cut-off point (≥ 60 years) has previously been reported in several studies to be directly linked to admissions to the intensive care unit and higher rates of morbidity and mortality [5, 14, 15]. Mechanisms of cerebral compensation, plasticity, and cerebral re-organization of the brain seem to be less effective with aging, so the adult brain has a decreased capacity for repair as it ages [6]. Moreover, pre-injury comorbidities and cognitive fragility in elderly patients may increase their vulnerability to the effects of brain insults [4, 14, 16]. Because of these vulnerabilities, older adults sustaining a brain injury may require more medical consultations, experience a greater number of medical complications, and have longer length of ICU and hospital stays due to lower physiological reserve available for recovery from injury compared to younger patients [6, 17]. Higher mortality rates in the elderly could also be explained by a lower intensity of care such as patients with malignant cerebral artery infarction that will not undergo decompressive surgery and a greater number of do-not-resuscitate orders [18].

Cumulative exposure to invasive mechanical ventilation in the general population has been associated with increased morbidity, long-term functional sequelae, and cognitive impairment [19], but with a significant decrease in short-term mortality over time [20,21,22]. However, previous analyses of the impact of mechanical ventilation on neurocritical patients’ outcomes have produced contradictory results. Similar to the current study, patients with brain injury displayed a longer duration of MV and a higher mortality rate despite a lower incidence of extracerebral organ dysfunction compared with non-neurologic patients in a multi-center nationwide observational study [2]. Whereas in another recent international multi-center study [23] that included 4152 mechanically ventilated patients due to different neurologic diseases, it was described that more lung protective ventilatory strategies have been implemented over years with no effect on survival, and a significant decrease in the duration of ventilator support in the most recent years. Other studies in the neuro-ICU field [24, 25] still suggested a long duration of MV, and it also did not alter the outcome. No clear recommendations are currently available for respiratory management of patients with acute brain injury, and this may contribute to institutional or individual variations in the clinical practice, and that may ultimately result in differences in the effect of mechanical ventilation on outcomes [1, 26, 27]. Moreover, likely, the impact of mechanical ventilation on outcome may also depend on a more severe brain injury, on the development of systemic complications, and even on high age [28]. Therefore, we have assumed that the need for mechanical ventilation as a surrogate marker for clinical severity is a very confounding variable, and we decided not to include it in the logistic regression analysis.

Various studies have evaluated prognostic admission factors for increased mortality in critically ill neurological patients with different results, but also with a high degree of agreement. As in the present study, advanced age, the severity of the disease (as defined by the GCS score and the development of intracranial hypertension), and the etiology of neurologic disease had also a strong influence on mortality in a recent international multi-center study despite differences in clinical practices between neurocritical care units [23]. Interestingly, although a high SAPS II score is a marker of clinical severity, the modified SAPS II score was not identified as a prognostic factor in the logistic regression analysis. This fact may be because the removed age and GCS components were precisely those that had the most weight on the overall SAPS II score. The etiology and severity of the head injury and a low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score have also been previously identified as predisposing factors for unfavorable outcomes in brain-injured patients [2, 5, 18, 29, 30]. Specifically, the diagnosis ICH has been shown that leads to reduced levels of consciousness, mechanical ventilation, and extended ICU stay, causing substantial disability and high early mortality [31,32,33]. Intracranial hypertension is also known as an independent risk factor for morbidity and mortality in patients with acute brain injury. This association is related to its negative effect on cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP), as hypoperfusion and the resultant brain tissue hypoxia contribute to secondary injury and poor short-term outcomes [33]. Several other factors have been associated with increased risk of mortality, such as high age and multiple injuries [3, 4, 7, 13], the necessity and duration of mechanical ventilation [2, 7, 28, 30], and severe comorbidities [4, 5, 18].

Our study has several limitations. First, pre-morbid levels of motor and cognitive functioning of the patients were not known. Several authors have shown that pre-existing chronic illnesses may also contribute to increased length of rehabilitation stay, a reduction in functional gains, and death [4, 15, 34]. Second, we have not followed the long-term evolution of patients after discharge from the hospital. Previous studies demonstrated a higher mortality rate at discharge among older adults within a few months post-injury may be due to the interaction between persisting injuries and chronic health conditions [8]. Third, we have only studied patients divided into two age groups. Since the effect of age on functional recovery is more likely to increase progressively over the life course, it could have been more interesting to examine also different age groups after 60 years [5]. Fourth, we did not collect details regarding the strategies applied for the treatment of intracranial hypertension, but we assume that brain-injured patients have been treated according to the most recent protocols and guidelines, and low variability in clinical practice given that the study was conducted at a single center and unchanged in staffing. Finally, the study population was heterogeneous, and it was conducted at a single center, so generalizability to other settings is uncertain, however, the results are consistent with a large number of other studies.

Conclusions

Data from this prospective study focusing on brain injury patients requiring admission in the ICU will provide detailed information on patient characteristics, clinical course, and outcomes. This highlights the impact of specific acute and unmodifiable parameters and may facilitate the assessment of prognosis after neurocritical care.

In summary, mortality and unfavorable functional outcomes in brain-injured patients requiring admission to ICU were associated with older age (≥ 60 years), higher clinical severity (determined by a lower GCS score at admission and the development of intracranial hypertension), and an intracerebral hemorrhage as the cause of neurologic disease.

References

Peñuelas O, Muriel A, Abraira V, Frutos-Vivar F, Mancebo J, Raymondos K et al (2020) Inter-country variability over time in the mortality of mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med 46:444–453

Pelosi P, Ferguson ND, Frutos-Vivar F, Anzueto A, Putensen C, Raymondos K et al (2011) Management and outcome of mechanically ventilated neurologic patients. Crit Care Med 39:1482–1492

Susman M, DiRusso SM, Sullivan T, Risucci D, Nealon P, Cuff S et al (2002) Traumatic brain injury in the elderly: increased mortality and worse functional outcome at discharge despite lower injury severity. J Trauma 53:219–224

Mosenthal AC, Lavery RF, Addis M, Kaul S, Ross S, Marburger R et al (2002) Isolated traumatic brain injury: age is an independent predictor of mortality and early outcome. J Trauma 52:907–911

Hukkelhoven CW, Steyerberg EW, Rampen AJ, Farace E, Habbema JD, Marshall LF et al (2003) Patient age and outcome following severe traumatic brain injury: an analysis of 5600 patients. J Neurosurg 99:666–673

LeBlanc J, de Guise E, Gosselin N, Feyz M (2006) Comparison of functional outcome following acute care in young, middle-aged and elderly patients with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 20:779–790

Lenell S, Nyholm L, Lewén A, Enblad P (2019) Clinical outcome and prognostic factors in elderly traumatic brain injury patients receiving neurointensive care. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 161:1243–1254

McIntyre A, Mehta S, Aubut J, Dijkers M, Teasell RW (2013) Mortality among older adults after a traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. Brain Inj 27:31–40

Mosenthal AC, Livingston DH, Lavery RF, Knudson MM, Lee S, Morabito D et al (2004) The effect of age on functional outcome in mild traumatic brain injury: 6-month report of a prospective multicenter trial. J Trauma 56:1042–1048

Reeder KP, Rosenthal M, Lichtenberg P, Wood D (1996) Impact of age on functional outcome following traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 11:22–31

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative STROBE (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 335:806–808

Esteban A, Anzueto A, Frutos-Vivar F, Alía I, Ely EW, Brochard L et al (2004) Outcome of older patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med 30:639–646

Vollmer D, Torner J, Jane J (1991) Age and outcome following traumatic coma: why do older patients fare worse? J Neurosurg 75(suppl):S37–S49

Ferrell RB, Kaloyan ST (2002) Traumatic brain injury in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep 4:354–362

Marquez de la Plata CD, Hart T, Hammond FM, Frol AB, Hudak A, Harper CR et al (2008) Impact of age on long-term recovery from traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 89:896–903

Canadian Institute for Health Information (2006) Head injuries in Canada: a decade of change. CIHI, Ottawa, ON

Thompson HJ, McCormick WC, Kagan SH (2006) Traumatic brain injury in older adults: epidemiology, outcomes, and future implications. J Am Geriatr Soc 54:1590–1595

Thompson HJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Wang J, Nathens AB, MacKenzie EJ (2008) Evaluation of the effect of intensity of care on mortality after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med 36:282–290

Rengel KF, Hayhurst CJ, Pandharipande PP, Hughes CG (2019) Long-term cognitive and functional impairments after critical illness. Anesth Analg 128:772–780

Esteban A, Anzueto A, Frutos F, Alía I, Brochard L, Stewart TE et al (2002) Characteristics and outcomes in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a 28-day international study. JAMA 287:345–355

Esteban A, Ferguson ND, Meade MO, Frutos-Vivar F, Apezteguia C, Brochard L et al (2008) Evolution of mechanical ventilation in response to clinical research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177:170–177

Esteban A, Frutos-Vivar F, Muriel A, Ferguson ND, Peñuelas O, Abraira V et al (2013) Evolution of mortality over time in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188:220–230

Tejerina EE, Pelosi P, Robba C, Peñuelas O, Muriel A, Barrios D, Frutos-Vivar F et al (2021) Evolution over time of ventilator management and outcome of patients with neurologic disease. Crit Care Med 49:1095–1106

Asehnoune K, Mrozek S, Perrigault PF, Seguin P, Dahyot-Fizelier C, Lasocki S et al (2017) A multi-faceted strategy to reduce ventilation-associated mortality in brain-injured patients. The BI-VILI project: a nationwide quality improvement project. Intensive Care Med 43:957–970

Roquilly A, Cinotti R, Jaber S, Vourc’h M, Pengam F, Mahe PJ et al (2013) Implementation of an evidence-based extubation readiness bundle in 499 brain-injured patients. A before-after evaluation of a quality improvement project. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188:958–966

Cnossen MC, Polinder S, Andriessen TM, van der Naalt J, Haitsma I, Horn J et al (2017) Causes and consequences of treatment variation in moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: a multicenter study. Crit Care Med 45:660–669

Bulger EM, Nathens AB, Rivara FP, Moore M, MacKenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ (2002) Management of severe head injury: institutional variations in care and effect on outcome. Crit Care Med 30:1870–1876

Barnato AE, Albert SM, Angus DC, Lave JR, Degenholtz HB (2011) Disability among elderly survivors of mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183:1037–1042

Broessner G, Helbok R, Lackner P, Mitterberger M, Beer R, Engelhardt K et al (2007) Survival and long-term functional outcome in 1,155 consecutive neurocritical care patients. Crit Care Med 35:2025–2030

Kiphuth IC, Schellinger PD, Köhrmann M, Bardutzky J, Lücking H, Kloska S et al (2010) Predictors for good functional outcome after neurocritical care. Crit Care 14:R136

Corbanese U, Possamai C, Dal Cero P (2004) Outcome of patients who underwent mechanical ventilation following intracerebral hemorrhage: is the glass really half full? Crit Care Med 32:1431

Roch A, Michelet P, Jullien AC, Thirion X, Bregeon F, Papazian L et al (2003) Long-term outcome in intensive care unit survivors after mechanical ventilation for intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care Med 31:2651–2656

Shen L, Wang Z, Su Z, Qiu S, Xu J, Zhou Y et al (2016) Effects of intracranial pressure monitoring on mortality in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 11(12):e0168901

Dijkers M, Gordon WA, Abreu B, Graham J, Charness A (2008) The intersection of aging/age and TBI: systematic review methodology. Brain Injury Prof 5:8–11

Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F (1993) A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA 270:2957–2963

Funding

This study was funded by Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Respiratorias (CIBERES).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tejerina, E.E., Gonçalves, G., Gómez-Mediavilla, K. et al. The effect of age on clinical outcomes in critically ill brain-injured patients. Acta Neurol Belg 123, 1709–1715 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-022-01987-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-022-01987-0