Abstract

Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG) deposits (PGNMID) is a rare kidney disease. The predominant pathological finding of PGNMID is the presence of monoclonal Ig deposits on the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). However, there is some variation in deposition pattern in this kidney disease. We report a case of steroid-sensitive recurrent mesangial proliferative type of PGNMID. A 40-year-old female noticed lower leg pitting edema and polyuria. Approximately 10 days prior to the first clinic visit, she was diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome based on the laboratory data of urine and blood. Immunological and hematological examination revealed no abnormality. However, kidney biopsy specimens showed mild mesangial cell proliferation and mesangial matrix accumulation on light microscopic findings. Regarding immunofluorescence staining, granular deposits of IgG, C1q, and β1c were observed on GBM and mesangial area. Granular deposits of IgG3 and λ were also observed on GBM and mesangial area. Moreover, negative results were obtained for the phospholipase A2 receptor antibody and thrombospondin type-1 domain-containing 7A. Electron microscopy revealed highly electron dense deposits mainly in the mesangial region. Kidney biopsy showed mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis characterized by monoclonal Ig deposition of IgG3/λ. Steroid therapy was initiated, and complete remission was achieved on day 36. After the discontinuation of steroid therapy, proteinuria recurred and second kidney biopsy findings were almost similar to the first biopsy. However, complete remission was achieved with steroid therapy. This is a rare recurrent case of steroid-sensitive PGNMID. The pathological feature of this case was mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with Ig deposition of IgG3/λ.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG) deposits (PGNMID) is a rare kidney disease. Clinical manifestations of PGNMID have been identified in some case reports; however, variations of this disease remain unclear. Patients presenting with PGNMID are typically middle aged, have massive proteinuria (including nephrotic-range proteinuria and hematuria), and have reduced glomerular filtration rate. Circulating monoclonal IgG is usually undetectable, and multiple myeloma is rare even during follow-up [1,2]. In some cases of kidney transplant, PGNMID recurs without detectable circulating monoclonal IgG [3,4]. However, pathological diagnosis of PGNMID remains unclear. In PGNMID, monoclonal Ig is deposited in the glomerulus. Monoclonal Ig deposition disease (MIDD) is similarly characterized by monoclonal Ig deposition in the glomerulus without a fibrillary or microtubular appearance on electron microscopy [5]. Remarkably, these two disease entities overlap. Steroid therapy is widely used to treat nephrotic syndromes such as PGNMID. It has been reported that steroid therapy or other immunosuppressive therapy usually has no effect on proteinuria [6]. However, some cases of PGNMID are reported to be sensitive to steroids [7, 8]. Therefore, a comprehensive review of steroid-sensitive cases may be essential for therapeutic management of this disease. Here, we report a case of steroid-sensitive recurrent mesangial proliferative type of PGNMID.

Case report

A 40-year-old female noticed lower leg pitting edema and polyuria approximately 10 days prior to the first clinic visit. However, school or workplace health screening did not reveal the presence of urinary protein, and her body weight increased by 4 kg prior to this episode. The patient was diagnosed with nephrotic syndrome based on laboratory investigation of urine and blood. She was referred to our hospital and admitted. Laboratory data indicated the following: urinary protein = 4 + (14.4 g/g creatinine) and occult blood = 1+. Selective index was 0.205. Blood biochemical analysis revealed a decrease in serum protein and albumin levels (4.1 and 1.2 g/dL, respectively). Kidney function was within the normal range (creatinine = 0.73 mg/dL, eGFR = 69.2 mL/min/1.73 m2). The serum IgG level was normal (925 mg/dL) and complement was preserved. The Ig free light-chain κ/λ ratio (0.896) was within the normal range (Table 1).

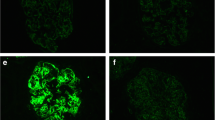

An antinuclear antibody (speckled × 40) and anti-SS-A antibody showed positive findings, whereas M-protein and cryoglobulin showed negative findings. No serological findings suggesting a monoclonal gammopathy were observed. A biopsy was performed to evaluate pathological changes in the kidney (Fig. 1). The kidney biopsy specimen contained a total of 18 glomeruli, 1 of which displayed total obsolescence (5.6%). Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining showed mild mesangial cell proliferation and mesangial matrix accumulation. Periodic acid methenamine staining revealed the absence of double contour or spike formation on GBM. Immunofluorescence staining showed granular deposits of IgG, C1q, β1c, IgG3, and λ on GBM and mesangial area (Fig. 2). In addition, immunoglobulin and complement deposits were absent on tubular basement membranes and arteries. Both phospholipase A2 receptor and thrombospondin type-1 domain-containing 7A were negative. Electron microscopy showed highly electron dense deposits in the mesangial region without any organized structures (Fig. 3). Irregular distribution of subepithelial or intramembranous deposits was also noted on GBM with the irregular effacement of podocyte foot processes. Based on the kidney biopsy findings, we diagnosed the patient with mesangial proliferative-type glomerulonephritis with monoclonal Ig deposition of IgG3/λ, and steroid therapy was initiated accordingly (Fig. 4). Patient showed complete remission on day 36 with steroid therapy; consequently, the steroid dose was gradually decreased and the therapy was discontinued after 21 months. Fifteen months after the discontinuation of steroid therapy, proteinuria (3.1 g/g creatinine) recurred. A second kidney biopsy was performed, the findings of which were almost similar to that of the first biopsy. Highly electron-dense deposits were mainly detected in the mesangial region on electron microscopy. Faint subepithelial and subendothelial deposits were observed. Steroid therapy was restarted, and the patient showed complete remission on day 6.

Pathological findings of the first kidney biopsy. The first kidney biopsy sections from the case show mild focal segmental mesangial cell proliferation and mesangial matrix accumulation in the glomeruli. a (×100) Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining, b–d ( × 400) Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining, periodic acid methenamine silver (PAM) staining, and Masson–trichrome (M–T) staining

Electron microscopy findings of the first kidney biopsy. Highly electron dense deposits (arrows) are mainly detected in the mesangial region by electron microscopy (a: ×4000). In addition to the mesangial deposits (arrows), irregular distribution of washout type or electron dense type of subepithelial electron dense deposits (arrows) is also noted on GBM (b: ×6000)

Discussion

We report a recurrent case of steroid-sensitive PGNMID with pathological features characterized by mesangial proliferation and monoclonal IgG deposition of IgG3/λ. Although PGNMID has not been well defined, it is a kidney-limited glomerular disease. Kidney biopsy shows membranoproliferative or endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis on light microscopy, monoclonal Ig and complement (commonly C3) deposits on immunofluorescence microscopy, and unorganized electron-dense deposits on electron microscopy [2]. While PGNMID may be similar to MIDD, these are distinct diseases with the latter showing light-chain and heavy-chain deposition, and it is defined by pathological accumulation of abnormally truncated monoclonal Igs in vascular, glomerular, and tubular basement membranes without a fibrillary, crystalline, or microtubular appearance on electron microscopy [9]. Therefore, the pattern of deposition is a differentiation feature distinguishing PGNMID from MIDD. In the present case, IgG deposits were only detected in glomeruli, and electron-dense deposits were unorganized on electron microscopy, leading to the diagnosis of PGNMID. Further, PAS staining showed mild mesangial cell proliferation and mesangial matrix expansion. Moreover, electron microscopy findings should show differentiation between PGNMID and LHCDD. MIDD with the linear punctate, powdery, granular deposits is recognized along the glomerular basement membrane, tubular basement membrane, and arterioles. However, in the present case, non-organized immune-complex type deposits were present in mesangial areas, indicating the PGNMID. Therefore, we diagnosed the patient with mesangial PGNMID. While membranoproliferative, membranous, and endocapillary proliferative type are common types of glomerulonephritis, crescentic and mesangial proliferative types are rare. Thus, our case is a rare type of PGNMID with mesangial proliferation.

Our patient had recurrent disease and was sensitive to steroid therapy. In general, PGMNID is resistant to steroid or immunosuppressive therapy and its prognosis is poor. Initial clinical course of this case is similar to minimal change nephrotic syndrome (MCNS). However, the selective index at the first admission was 0.205. Although the response to treatment with steroids was good, it took more than 1 month to achieve complete remission after the steroid pulse therapy. These clinical manifestations were inconsistent with MCNS. Currently, there is no standardized therapy for this disease, and approximately 25% patients progress to dialysis within 3 years of diagnosis [2]10. A previous case series on 37 patients with PGNMID reported only 12.5% patients with complete recovery after 30.3-month follow-up [2]. A study on clinical outcomes showed a higher percentage of glomerulosclerosis was the only independent predictor of end-stage renal disease. Moreover, progression of total glomerulosclerosis and tubular interstitial and vascular injury were shown to be poor prognostic factors [2]. Compared with that study, the present study had total obsolescence glomeruli of 5.6%. Among various treatments available for PGNMID, steroid therapy is the most common and has been reported to be effective for proteinuria in PGNMID in some cases [11], 12. Especially in MN type and mesangial proliferative type of PGNMID, it has been reported that steroid therapy was effective [7,8,12]. In addition, Takayuki and Tomomi et al. reported cases in which steroid treatment was effective for PGNMID [13,14]. Although it was reported that steroid would be effective for some part of PGNMID cases, including our case, the mechanism of steroid sensitivity is unclear so far. Steroid may reduce the production of monoclonal IgG3λ and prevent pathological changes [7, 8, 12]. This might be one of the possible mechanisms of steroid sensitivity. Therefore, we selected steroid therapy as the initial treatment. Moreover, PGNMID has a high recurrence rate in renal allografts with normal serological test [13,14,15]. In some cases, rituximab was useful for recurrent PGNMID after kidney transplantation [16]. In addition to the steroid and/or rituximab treatments, bortezomib, mycophenolate mofetil, and/or daratumumab were reported to be candidate treatments for PGNMID [17]. In the present case, recurrence was observed after steroid therapy was discontinued, and the patient went into complete remission again with steroid therapy. Furthermore, pathological findings of second kidney biopsy were almost similar to the first biopsy findings in our case. Steroid therapy may have beneficial effect in progression of pathological changes. Thus, our case is a rare type of mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis that showed sensitivity to steroid therapy two times.

Proteinuria recurred in our case 15 months after the discontinuation of steroid therapy, and the patient showed complete remission on day 6 after steroid therapy. The findings of second kidney biopsy were almost similar to the first biopsy. Instead of immune complex deposition disease, steroid response was very good in the recurrent proteinuria. Although this point would be a unique clinical manifestation in this case, it is hard to clearly explain it. Accumulation of similar cases and additional pathophysiological analysis are required to clarify the pathogenesis of this disease. From this perspective, we consider this case to be informative and of sufficient clinical significance. Further studies are needed to identify factors that render PGMNID sensitive to steroids in each pathological type.

In conclusion, we reported a rare and clinically significant case of steroid-sensitive recurrent PGNMID with mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis as the primary pathological feature. Further studies are required to reveal its pathogenesis and responsiveness to treatment.

References

Gumber R, Cohen JB, Palmer MB, et al. A clone-directed approach may improve diagnosis and treatment of proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal immunoglobulin deposits. Kidney Int. 2018;94(1):199–205.

Nasr SH, Satoskar A, Markowitz GS, et al. Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(9):2055–64.

Lusco MA, Fogo AB, Najafian B, et al. AJKD atlas of renal pathology: proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal immunoglobulin deposits. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(3):e13-15.

Kousios A, Duncan N, Tam FWK, et al. Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal Ig deposits (PGNMID): diagnostic and treatment challenges for the nephrologist! Kidney Int. 2019;95(2):467–8.

Aly OE, Black DH, Rehman H, et al. Single incision laparoscopic appendicectomy versus conventional three-port laparoscopic appendicectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2016;35:120–8.

Masai R, Wakui H, Komatsuda A, et al. Characteristics of proliferative glomerulo-nephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits associated with membranoproliferative features. Clin Nephrol. 2009;72(1):46–54.

Komatsuda A, Masai R, Ohtani H, et al. Monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disease associated with membranous features. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(12):3888–94.

Omokawa A, Komatsuda A, Hirokawa M, et al. Membranous nephropathy with monoclonal IgG4 deposits and associated IgG4-related lung disease. Clin Kidney J. 2014;7(5):475–8.

Gerth J, Sachse A, Busch M, et al. Screening and differential diagnosis of renal light chain-associated diseases. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2012;35(2):120–8.

Ranghino A, Tamagnone M, Messina M, et al. A case of recurrent proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits after kidney transplant treated with plasmapheresis. Case Rep Nephrol Urol. 2012;2(1):46–52.

Ohashi R, Sakai Y, Otsuka T, et al. Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG2kappa deposit successfully treated with steroids: a case report and review of the literature. CEN Case Rep. 2013;2(2):197–203.

Komatsuda A, Wakui H, Ohtani H, et al. Steroid-responsive nephrotic syndrome in a patient with proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits with pure mesangial proliferative features. NDT Plus. 2010;3(4):357–9.

Katsuno T, Kato M, Fujita T, et al. Chronological change of renal pathological findings in the proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits considered to have recurred early after kidney transplantation. CEN Case Rep. 2019;8(3):151–8.

Tamura T, Unagami K, Okumi M, et al. A case of recurrent proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits or de novo C3 glomerulonephritis after kidney transplantation. Nephrology (Carlton). 2018;23(Suppl 2):76–80.

Said SM, Cosio FG, Valeri AM, et al. Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal immunoglobulin G deposits is associated with high rate of early recurrence in the allograft. Kidney Int. 2018;94(1):159–69.

Merhi B, Patel N, Bayliss G, et al. Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits in two kidney allografts successfully treated with rituximab. Clin Kidney J. 2017;10(3):405–10.

Torrealba J, Gattineni J, Hendricks AR. Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal immunoglobulin G lambda deposits: report of the first pediatric case. Case Rep Nephrol Dial. 2018;8(1):70–5.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded only by the resources of our departments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

All the authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient in the case report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

About this article

Cite this article

Nomura, K., Miyatake, N., Okada, K. et al. Steroid-sensitive recurrent mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits. CEN Case Rep 10, 308–313 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13730-020-00562-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13730-020-00562-x