Abstract

Emerging research shows teachers and architects perceive higher numbers of affordances for learning in innovative learning environments (ILEs) than in traditional classrooms. Yet, offering ILEs alone will not bring about significant changes to teacher practices nor students’ learning experiences. Supporting teachers to perceive and utilise spaces that offer multiple activity settings, such as afforded by ILEs, is important in eliciting pedagogical change. This research explored the development of strategies intended to support teachers to actualise the affordances of ILEs, i.e. take advantage of new learning spaces for effective teaching and learning. An innovative methodological pairing of Participatory Action Research (PAR) and Co-design was employed to explore teachers’ instructional practice development in relation to new learning spaces. The study uncovered insights into current and future practices, where teacher participants planned, enacted, and reflected upon their pedagogical strategies. It was found that empowering teachers to actualise ILE affordances involved generating communities of practice that provided them with the ‘time and space’ to collectively develop their practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Situated within a larger project investigating teacher adaptation to innovative learning environments (ILE), this research specifically focussed on the relationships between teachers’ practice and the affordances of ILEs. Through an iterative research process, strategies and tools to help teachers actualise the affordances (action possibilities) of ILEs were developed and trialled with the aim of assisting teachers to maximise the pedagogical opportunities of new spaces for deep learning (Fullan & Langworthy, 2013; Mahat et al., 2018).

The research reported was derived from two separate but overlapping PhD studies positioned within the larger project. An innovative methodological pairing of Participatory Action Research (PAR) and Co-design was employed to connect the two studies and explore teachers’ practice development in relation to new learning spaces. The approach developed is described as a novel offering of the research that was undertaken.

Fieldwork was conducted at two secondary schools, both seeking to develop new pedagogies amidst the process of transitioning into ILEs. The studies engaged teachers as both participants and co-researchers, involving them in planning, enacting, and reflecting upon pedagogical development in relation to the affordances of new learning spaces.

Background

Innovative learning environments (ILEs)

Intended to support more student-centred pedagogies as opposed to teacher-centred instruction (Dovey & Fisher, 2014; Imms et al., 2016; OECD, 2013), innovative learning environments (ILEs) are commonly emerging in place of traditional classrooms in Australian and New Zealand schools. Designed to facilitate a variety of collaborative, participatory, and independent teaching and learning approaches, ILEs may ‘become’ effective socio-spatial contexts for learning as “the product of innovative space designs and innovative teaching and learning practices” (Mahat et al., 2018).

Typically, ILEs comprise interconnected spaces with high levels of visibility across and between varied learning settings that help situate different teaching and learning activities. Zones within these interconnected spaces often include settings for large groups to gather for organisational or direct instruction, enclosable spaces for small group collaboration, and areas for hands-on activities (Young et al., 2019). Agile furniture and technologies may enable spaces to be adapted for different purposes, supporting students and teachers to modify their environment to meet their needs.

Space, pedagogy and practice

Emerging research shows higher numbers of affordances for learning are perceived by both teachers and architects in ILEs than in traditional classrooms (Young et al., 2019). This indicates that ILEs may offer more options for teaching and learning activities; nevertheless, the literature highlights that actualising affordances for teaching and learning can be hindered by entrenched cultures, practices and a lack of vision for ‘doing things differently’ (Cleveland, 2018; French et al., 2019). While ILEs are intended to support contemporary teaching and learning practices, researchers have noted that offering ILEs alone will not bring about significant changes to teacher practice (Blackmore et al., 2011; Cleveland, 2011; Gislason, 2010; Halpin, 2007; Lackney, 2008; Mulcahy et al., 2015; Woolner et al., 2012). Halpin (2007) stated that open-plan school designs are just as likely to “act as containers for conventional as much as for more enlightened modes of teaching and learning” (p. 251) and suggested that the key variable for the success of ILEs “is not space, but teachers’ intentions and educational aims in terms of how they go about using it” (p. 251).

As discussions about space as a pedagogical tool are not common in educational discourse, teachers may not readily perceive links between the affordances of the physical environment and effective teaching and learning (Lackney, 2008; Newton, 2009). Since the 1970s, studies investigating teachers’ use of contemporary learning spaces have illustrated the difficulties of changing practice in new spaces (Cleveland & Woodman, 2009; Cotterell, 1984; Deed & Lesko, 2015; Rivlin & Rothenberg, 1975; Woolner et al., 2007). Indeed, many researchers have suggested that there is a need to support teachers to work effectively in new learning spaces (Blackmore et al., 2011; Brogden, 2007; Cotterell, 1984; Deed & Lesko, 2015; Halpin, 2007).

Affordance theory

Psychologist James Gibson developed the concept of affordances to refer to an action possibility resulting from the complementary relationship between the environment and user (Gibson, 1979). He proposed that affordances can exist in the environment whether they are used or not, and that users must first perceive them in order to use them. Affordances may remain latent as potential affordances until recognised by individuals, and even if/when seen, individuals must show intentions towards them, plus have the physical ability to use them, if they are to be actioned.

Heft (1989) described the relationship between the perception and utilisation of affordances as being one of ‘actualisation’. Later, Kyttä (2002, 2004) identified that individuals’ abilities to actualise affordances can be influenced by cultures, social settings and prior experiences, thus shaping how they perceive and utilise the affordances around them. People may also learn to recognise affordances they may not previously have perceived (Gibson & Pick, 2003).

Strategies and tools to support actualisation of affordances in ILEs

Successfully actualising affordances for teaching and learning may involve dealing with an array of factors beyond direct human–environment relations (Young et al., 2019). Lindberg and Lyytinen’s (2013) affordance ecology model, which identifies organisation, infrastructure and practice as high level domains, provides a useful framework through which to consider the nature of affordances in education contexts. A shift in focus from what action possibilities should be afforded by new learning spaces to how teachers can best take advantage of ILEs in support of deep learning (Fullan & Langworthy, 2013; Mahat et al., 2018) has brought into focus the need to find ways of encouraging teachers to think more critically and creatively about the relationships between pedagogy and space.

The specific purpose of this research was to seek insights into how teachers can be supported to perceive, utilise and shape affordances for teaching and learning within ILEs. By working with teachers on practice change, this research explored the development of ‘strategies’ and ‘tools’ to support teachers to actualise the affordances of ILEs for deep learning.

Methodology

An interdisciplinary approach

An innovative methodological pairing of Participatory Action Research (PAR) (Cohen et al., 2007; Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005) and Co-design (Melo et al., 2018) was employed to explore teachers’ practice development in relation to new learning spaces. Adopting an interdisciplinary approach, the research aimed to integrate information, methods, data, tools, concepts and theories from distinct bodies of knowledge (Klein, 2015). The interdisciplinary methods employed helped generate new knowledge in partnership with teachers through the integration of their lived experience within the research framework.

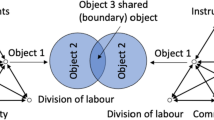

The overall research design is illustrated in Fig. 1. Framed by an embedded single case study approach (Yin, 2014), the unit of analysis was teachers from two girls’ secondary schools involved in the process of transitioning into new ILEs. The object under investigation was teacher’s actualisation of learning environment affordances. The PAR methodology directed the research process, while Co-design workshops and semi-structured interviews were used as tools for data collection.

Both PAR and Co-design explore sites of social practices through activity and collective conversations. PAR is known as a ‘practice-changing-practice’ approach which aims to “change practices, people’s understandings of their practices, and the conditions under which they practice” (Kemmis et al., 2014, p. 59). Similarly, Co-design employs ‘designerly’ modes of inquiry, as participants make and ‘show’ their voice through a material heuristic (Sanders et al., 2012). These approaches informed workshops in which the researchers actively involved teachers in design processes to ensure the designed outcomes met their needs. In this way, the pairing of PAR and Co-design strategies provided a pathway for participants to reflect on their own practices and gain deeper insights into the sites of their practice.

Participatory action research

Cohen and Manion (1994) described action research as a social practice applicable when “specific knowledge is required for a specific problem in a specific situation, or when a new approach is to be grafted on to an existing system” (p. 194). To this end, this research paid particular attention to the cultural and organisational contexts of participant schools while exploring how teachers experience practice development within new ILEs.

In a PAR process, participants themselves are considered co-researchers (rather than the researched) and are expected to make decisions about what to explore and what to change. PAR provides the conditions for participants to become members of a community of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015), to develop improved understandings of their current situations, and to determine what actions may be required to both individually and collectively transform practices to meet the needs of changing times and circumstances (Kemmis et al., 2014). In so doing, participants take ownership, empowering them in the process of change. Through an iterative cycle, participants plan change(s), act and observe change(s), reflect on the process and consequences of change(s), and then re-plan, act, observe and reflect again. In this way, a “feedback loop in which initial findings generate possibilities for change … [is anticipated] … implemented and evaluated as a prelude to further investigation” (Denscombe, 2014, p. 123).

Designing as method: from design thinking to co-design

A report published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), titled Teachers as Designers of Learning Environments (Paniagua & Istance, 2018), notes that pedagogy needs to be combined with expertise in the design of learning spaces for teachers to take advantage of ILEs. The report highlights that “teacher learning—collaborative, action-orientated, and co-designed—is fundamental to change” (Paniagua & Istance, 2018, p. 43). The authors suggest that alongside the capacity for active collaboration, the ability to ‘co-design’ is required if change in learning environments is to be enacted. Like the OECD report, this study appreciated how well-intentioned architectural design has given shape to the emergence of ILEs, but asked how engaging in co-design processes could bring them to life.

Co-design has emerged from a suite of ‘design thinking’ approaches that work towards innovative transformation. According to Plattner et al. (2015), design thinking involves a process that is human-centred, works with ambiguity and makes ideas tangible. Design thinking workshops engage stakeholders directly, working through ambiguity, albeit using tangible materials. In the context of this study, design thinking offered an opportunity to co-create with teachers and form a rich understanding of the research landscape (Plattner et al., 2015). One teacher noted “doing hands-on activities with these teachers I don’t get to spend a lot of time with, and to do different things, that sort of broke down the barriers and got us working as a team” (Teacher A, School A). This capacity, to ‘read’ and ‘write’ through design, engaged participants not only as an instrument or method but as a response to the broader demands of practice transformation (Barry et al., 2008).

School site selection

Two groups of 11 and 14 teachers from two different girls’ secondary schools in Sydney, Australia were recruited to participate. Both schools were in the process of designing, constructing and inhabiting new ILEs.

School A is a Catholic girls’ secondary school with a population of nearly 1000 students. The school has an agenda to transform learning in order to build students’ capacity to learn, create and adapt to a fast-changing world. This transformation agenda relates to five key components including pedagogy, professional learning, pathways, partnerships and learning spaces. Major improvement of buildings and therefore learning spaces is seen to be one of the components required to support the schools’ transformation agenda. While learning spaces at the school have predominantly comprised single-celled traditional classrooms, plans for new buildings include ILEs.

School B is also a Catholic girls’ school. At the time of the research, it had an enrolment of 675 students. The school’s learning philosophy is based on the concept of growth mindset (Dweck, 2012), supporting a view that students’ talents and abilities can be developed through effort, good teaching and persistence. The majority of learning spaces at the school were traditional classrooms, with the exception of a small 200 square metre classroom block that had recently been refurbished into a prototype ILE space: a dynamic new space intended to support teachers’ practice development in advance of transitioning into a large Year 7 and 8 learning centre and whole school library designed around ILE concepts. The prototype space was able to be occupied by two or three classes of 25 students at the same time, offering a range of affordances for learning.

Figure 2 depicts the range of purposeful spaces for different sized groups in the prototype ILE space: a large tiered space for performance and presentation, a tutorial space for whole class groups, smaller enclosable spaces for small group meetings or retreat, booth seating and different types of furniture for varied activities.

Method

Data collection was conducted over a series of six workshops and two rounds of interviews, informed by an adapted PAR cycle (Fig. 3). The first four workshops focussed on the exploration of strategies to support teachers to actualise the affordances of ILEs. Based on findings from the initial four workshops, tools to support affordance actualisation for teaching and learning were developed and tested over the final two workshops.

Within each participating school, a specific research question positioned the focus of the study. The question asked at School A was How can we prepare ourselves to effectively use our proposed new learning spaces? Whereas the question asked at School B was How can we enhance our use of our new prototype learning space for student deep learning?

Informed by the phases of the PAR cycle, each workshop had a different focus (see Table 1). All workshops were designed and facilitated by the researchers; however, the issues explored were largely determined by the co-researchers/participants (i.e. teachers).

Reconnaissance phases generated insight into the socio-spatial contexts at each school. Workshop One engaged teachers in discussion about the affordances of their learning spaces. Using transparencies onto which a range of spatial qualitiesFootnote 1 were printed, teachers were asked to associate spatial qualities with learning principles [adapted from Mattingly (2016)] (see Fig. 4).

In matching spatial qualities with learning principles, teachers identified the spatial qualities that either enabled or constrained their practice. In doing so, they were able to identify the action possibilities for effective teaching and learning associated with a variety of affordances.

Workshop Two focussed on reviewing emerging themes as well as related data arising from the semi-structured interviews conducted with workshop participants/co-researchers (see interview questions in Appendix). This workshop produced a series of felt concerns (Kemmis et al., 2014), which teachers subsequently developed into initiatives to drive further exploration (see Table 2).

Workshop Three was framed around the metaphor of ‘outer space’. This metaphor was used as a vehicle to elicit participant reflection on the initiatives they had trialled arising from Workshop Two. Participants worked in small groups to ‘build’ representations of the factors influencing their practice (Fig. 5). Each group was given a ‘planet’ to represent their practice and used a variety of materials to construct representations of learning environment affordances that ‘orbited’ their planet. Enabling affordances, such as ‘space stations’ (for example, reflecting teacher planning/collaboration zones) and constraining affordances, such as ‘black holes’ (for example, reflecting students unable to cope with excessive noise), were identified. After discussing each groups ‘planet’ (practice) and ‘orbiting objects’ (affordances), participants were asked to link their planets to other groups’ ‘orbiting objects’, to help identify additional affordances that might better support their own practice.

Workshop Four involved teachers drawing spatial arrangements (annotated floor plans) to represent their changing practice. They were asked to represent their practice both before and after changes had been made as an outcome of the research process (Fig. 6). A second round of semi-structured interviews with all teacher participants/co-researchers followed Workshop Four (refer Appendix).

Following synthesis of the findings arising from the initial four workshops, an additional two workshops were designed by the researchers. Workshop Five focussed on priming participants to ‘perceive’ affordances of their old/existing learning spaces and their new ILEs. The workshop explored teacher perceptions associated with changes in practice that they believed would need to occur if they were going to teach effectively in the new learning spaces.

The final workshop, Workshop Six, focussed on supporting teachers to engage in conversations about what might help them actualise the affordances of their new ILE spaces. Newly created workshop tools were intended to help teachers better understand learning environment affordances and consider how they might develop new individual (i.e. single teacher) and collective (i.e. multiple teachers) abilities to perceive and utilise them (see Fig. 7).

All workshop sessions and interviews were audio recorded. These were transcribed and coded in NVivo using a thematic analysis approach adapted from Braun and Clarke (2006). In keeping with the PAR research approach, data were shared with teachers to draw out participant/co-researcher comments offering deeper insights into the study.

Findings and discussion

Transitioning into ILEs: key issues identified

During the initial reconnaissance and planning phases of the PAR process, teachers discussed a range of common issues relating to their old/existing learning spaces. Many felt that traditional classroom layouts, with students sitting in rows, dictated passive learning behaviours, limiting pedagogical diversity and student engagement. Challenges related to timetables, teaching in multiple classrooms and limited protocols for sharing spaces with other teachers/classes. These were identified as prohibiting varied classroom layouts and the creation of multiple activity settings.

At School B, where teachers had access to a new prototype ILE, responses ranged from excitement about enabling more diverse teaching and learning opportunities afforded by the spaces, to not knowing how to use the spaces in ways that differed from their traditional classroom practice.

Across both schools, the main concerns related to transitioning into ILEs included:

-

Teaching collaboratively with other teachers;

-

Logistics associated with sharing ILE spaces;

-

Releasing control of students’ movements and activities; and

-

Ensuring that students did not ‘slip through the cracks’ (i.e. monitoring student activity and progress).

These issues were articulated by teachers as a series of felt concerns, which they phrased as questions. These are outlined in Table 3.

Planning to address teachers’ felt concerns generated a series of themes considered supportive of practice change. They included:

-

Being part of a community of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015) of teachers across key learning areas, focussed on relationships between pedagogy and space;

-

Creating opportunities to trial and test new practices;

-

Observing other teachers practice and receiving feedback on one’s own practice;

-

Visualising ideas about the potential use of space (i.e. perceiving and actualising affordances);

-

Creating time to plan lessons together in support of team-teaching (i.e. recognising how non-spatial aspects of the affordance ecology may also need to shift).

Creating communities of practice

Reflecting on their PAR and Co-design experiences, teachers reported that the most impactful part of the research was simply belonging to a community of practice that engaged in collective learning in a shared domain. The opportunity to have regular discussions with teachers across key learning areas was of particular benefit in shaping individuals' understandings of the relationships between pedagogy of space.

Through discussion, teachers were exposed to others’ experiences and ideas related to the pedagogical use of spatial affordances and gained insights into how other teachers approached teaching and learning in different environments. A teacher at School B reflected:

We kind of figured out what worked, what didn’t work and what kind of things do we enjoy doing: what are we comfortable with in the classroom. You know, some of my boundaries are different to say Jodi’s (pseudonym). So things that she values and are important to her aren’t necessarily mine. So it’s about contextualising that use of space for different teachers and different personalities. (Teacher C, School B).

Teachers’ recognition of the importance of participating in a community of practice highlighted the importance of a collective approach to practice change and the need to generate both collective and individualised visions for how new spaces could be used differently/better for teaching and learning.

Trialling and testing new practices

The trialling and testing of various initiatives to address teachers’ felt concerns was found to be important in providing them with first-hand experience in how new spaces could be used to support their practice. One teacher recognised that the act of trialling new approaches was critical to becoming empowered in the process of change:

The biggest thing that’s come out … is trying to make us feel less uncertain and more empowered … to interrogate what we do, but not be afraid of trying new things. I think for me … the overall impact is to just try things. Have a go, you know. The girls aren’t going to not learn anything and you’ve just got to … take that leap of faith. (Teacher D, School B).

These findings align with those of Lackney (2008), who suggested that teachers are more likely to gain insights into how the physical environment can support teaching and learning from direct experience and experimentation, as opposed to formal education or training.

The act of trialling spatio-pedagogical initiatives alongside other teachers and collectively reflecting on such trials was found to empower teachers in the use of spatial affordances. Such activity also helped reduce their concerns about deviating from current/familiar practices and the potential risks associated with practice change.

Observing practice and providing feedback

Central to the process of testing new practices was the trialling of team-teaching. In this context, a few teachers asked others to observe their practice and provide feedback. Observing others helped teachers perceive affordances for teaching and learning activities which they had not previously perceived. One teacher spoke about the benefits of having another teacher to help raise awareness of her own practice:

That was really illuminating to me to have my colleagues give me feedback on things that I had noticed and things that I hadn’t noticed … I found that really helpful and really effective in terms of actually making me consider how I make a few changes … This space I love, but Sarah (pseudonym) observed one of my lessons and she said to me, “you know, some of the students have their back to you”, and I said “yeah I know but like there’s not enough seats and then if I get them to move I lose too much time”. And then we kind of talked about that and it made me think a bit more divergently. (Teacher F, School B).

In addition to being observed, being the observer also helped teachers perceive affordances for teaching and learning which they had not recognised, or considered, earlier. A teacher at School B reflected:

It’s enabled me to observe how other teachers teach for a start and it’s made me think ‘oh that’s a really good way of outlining that sort of concept or that’s a good way of giving that instruction’. For me, my practice is going to improve by seeing how others approach the teaching. But I really, really, really like just having another teacher there so that I can quickly share notes with them and say ‘hey this is going on, what do you think I should do' … it’s really good as well for the girls to see teachers collaborating together. I think it’s really good for them to see us collaborating and see that we’re learning as well … a sense that teaching is a very dynamic process, it’s always evolving just as the learning is. (Teacher D, School B).

Sharing ideas about the potential use of space

School A teachers were constrained in their ability to trial team-teaching. Due to a lack of suitable spaces, most trials involved rearranging furniture within classrooms to create differentiated learning settings. Spatial trials at School A also involved educating students about why spaces were being rearranged. One teacher created posters of classroom layouts to help illustrate the affordances provided by the furniture settings she had developed. She reported that seeing the potential use of spaces in diagrams enabled students to more readily perceive and utilise different learning settings. The same teacher noted that having diagrams up on the wall also encouraged teachers who were not involved in the research to trial new settings/spatial arrangements. She said:

I did a lot of training my class with the different space [arrangements] and how they would use the space … I even did posters about these different kinds of spaces and this is what we do in this space and I went through that with the girls. Then one of the other teachers that used the same classroom decided to take it up, so she put posters on the wall. We had two classes doing the same thing in the same room so that helped as well. (Teacher B, School A).

Teachers also noted the positives associated with other teachers around them trialling new ideas and practices—including some outside the research group who became engaged in trying to take advantage of new spaces for pedagogical benefit. These findings highlighted the importance of promoting school-wide ‘visibility’ of learning environments research in order to engage a wider audience and share the process and outputs of the research.

Shifting time and other non-spatial aspects of the affordance ecology

The range of issues and themes that emerged were broader than many participants/co-researchers expected. Through the research process many preconceptions about the uses and challenges of actualising the affordances of ILEs were demystified through wide ranging discussions about various factors enabling or constraining practice development/change.

Perhaps not surprisingly, many non-spatial matters were found to influence the actualisation of affordances in ILE spaces. These matters included organisational issues, such as timetabling, meeting schedules for teacher planning, providing time for the trialling of new practices, and opportunities for communities of practice to meet. To this end, Lindberg and Lyytinen’s (2013) ‘affordance ecologies’ framework, which comprises infrastructure, organisation and practice dimensions, was recognised as useful in the context of affordance actualisation within ILEs for categorising spatial and non-spatial dimensions. Highlighting how organisation and practice related matters may enable or constrain direct human–environment relationships helped reveal that affordance actualisation does not simply concern the activation of spaces, but necessitates shifting the cultural norms that operate within schools. Indeed, updating organisational structures was identified as a critical enabler of practice change in the participating schools (see Fig. 8).

Affordance ecology diagram adapted from Lindberg and Lyytinen (2013) showing emergent themes supporting teachers transition into ILEs

Conclusion

This research explored the development of an interdisciplinary approach to supporting teachers to actualise the affordances of ILEs. Significantly, the study generated insights into current and future practices, where teacher participants planned, enacted, and reflected upon their pedagogical strategies. This involved an expression of teacher expertise through collaborative and creative methods as part of a PAR strategy, enabling exploratory conversations about practice change. These methods formed a relationship between practice development and new learning spaces that was generative and revelatory.

Issues such as time or teacher agency were revealed as critically important. Reflecting on their participation in the research, one teacher noted:

You can’t really fast track it because you’ve got to have time to go and put it into practice and try a few different times … and then see how it works and go and talk to somebody else and fiddle with what you’re doing and have another practice at it. (Teacher B, School A).

Both the PAR and Co-design methodologies positioned teachers as researchers of their own practice and gave them agency to investigate the use of space, empowering them in the process of change. Further, combining the PAR framework with Co-design tools gave participants freedom to explore, while ensuring some structure was present to direct the research process. A senior teacher at School B felt that the research had enabled them to delve deeply into issues around practice change. She noted:

As teachers – and even as an executive – we sometimes jump to the product and we just want a framework or guidelines to tick a box. But this process really has been about experimentation and play and discovery for teachers which is really valuable. (Teacher C, School B).

It was also encouraging to see the Co-design tools used in many of the workshops generate some very open-ended discussions, ultimately helping teachers recognise the potential of space as a teaching and learning resource. Through discussions held over a number of months, teachers became more aware of the affordances of new spaces. They also increasingly came to recognise how different spaces influenced students’ learning activities and experiences. In describing the impact of the research on teachers, a School B teacher responsible for leading professional development noted:

I think those workshops and the way that they ran, took them (teachers) to the place that they needed to be. If I got up at a staff development I don’t think they would have come to that realisation on their own. It would’ve been me telling them. But I feel like that journey … they came to that point on their own. (Teacher E, School B).

While there is increasing interest in the potential of ILEs to support more diverse pedagogies in support of student engagement and learning, less awareness or understanding exists about how to support teachers’ transition into new spaces. This study revealed that with supporting structures in place teachers could become comfortable in exploring ‘new’ pedagogical approaches and work more closely with colleagues. These structures involved ongoing workshops which generated individual and collective insights into the affordances, or action possibilities, of new spaces. This in turn encouraged strategies to actively avoid a propensity to revert to default teaching practices developed through long-established experience and understandings of traditional classrooms.

Considering learning environment affordances within a wider context (i.e. beyond direct human–environment relations) was also found to be important. To this end, the adoption of the ‘affordance ecologies’ framework proposed by Lindberg and Lyytinen (2013) is suggested to be useful in bringing people’s attention to both spatial and non-spatial dimensions, such that may influence affordance actualisation within ILEs. Indeed, this research identified that many non-spatial matters had an influence on teachers’ practice change in ILE spaces: timetabling, meeting schedules for teacher planning, time for trialling and testing new practices, and opportunities for teachers to meet and reflect as communities of practice.

This study has established an interdisciplinary research trajectory and opportunity for further exploration of critical research methodologies in the context of ILEs and pedagogical change. The methods employed in this study allowed the relationships between practice development and new learning spaces to be understood in ways that were both generative and revelatory. Nevertheless, further research about how teachers develop, implement and sustain new practices in new learning spaces is required—especially of a longitudinal nature. The study also offers insights into the types of ‘tools’ and ‘strategies’ that may assist teachers to develop their spatialised pedagogic practices, such that may assist them to more effectively actualise affordances for learning.

Notes

The spatial qualities of learning spaces included those identified by Young et al. (2019).

References

Barry, A., Born, G., & Weszkalnys, G. (2008). Logics of interdisciplinarity. Economy and Society, 37(1), 20–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140701760841.

Blackmore, J., Bateman, D., Loughlin, J., O’Mara, J., & Aranda, G. (2011). Research into the connection between built learning spaces and student outcomes. (Vol. 22). Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brogden, M. (2007). Plowden and primary school buildings: A story of innovation without change. [Conference proceedings]. Forum, 49(1), 55–66.

Cleveland, B. (2011). Engaging spaces: Innovative learning environments, pedagogies and student engagement in the middle years of school. PhD Thesis, The University of Melbourne.

Cleveland, B. (2018). Innovative learning environments as complex adaptive systems: Enabling middle years’ education. In B. Lofland, & J. M (Eds.), Transforming education, (pp. 55–78). Singapore: Springer.

Cleveland, B., & Woodman, K. (2009). Learning from past experiences: School building design in the 1970s and today. In C. Newton & K. Fisher (Eds.), TAKE 8 learning spaces: The transformation of educational spaces for the 21st century. (pp. 58–67). Australian Institute of Architects.

Cohen, L., & Manion, L. (1994). Research methods in education. (4th ed.). Routledge.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education. . Routledge.

Cotterell, J. L. (1984). Effects of school architectural design on student and teacher anxiety. Environment & Behavior, 16(4), 455–479.

Deed, C., & Lesko, T. (2015). Unwalling the classroom: Teacher reaction and adaptation. Learning Environments Research, 18(2), 217–231.

Denscombe, M. (2014). The good research guide: For small-scale social research projects. . Open University Press.

Dovey, K., & Fisher, K. (2014). Designing for adaptation: The school as socio-spatial assemblage. The Journal of Architecture, 19(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2014.882376.

Dweck, C. (2012). Mindset: How you can fulfil your potential. . Constable & Robinson.

French, R., Imms, W., & Mahat, M. (2019). Case studies on the transition from traditional classrooms to innovative learning environments: Emerging strategies for success. Improving Schools, 23(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480219894408.

Fullan, M., & Langworthy, M. (2013). Towards a new end: New pedagogies for deep learning. . Pear Press.

Gibson, E., & Pick, A. (2003). An ecological approach to perceptual learning and development. . Oxford University Press.

Gibson, J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. . Houghton-Mifflin.

Gislason, N. (2010). Architectural design and the learning environment: A framework for school design research. Learning Environ Research, 13(2), 127–145.

Halpin, D. (2007). Utopian spaces of “robust hope": The architecture and nature of progressive learning environments. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 35(3), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660701447205.

Imms, W., Cleveland, B., & Fisher, K. (2016). Evaluating learning environments: Snapshots of emerging issues, methods and knowledge (Advances in learning environments research). . Sense Publishers.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (2005). Participatory action research: Communicative action and the public sphere. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. (3rd ed., pp. 559–604). SAGE Publications.

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. . Springer.

Klein, J. T. (2015). Interdisciplining digital humanities: Boundary work in an emerging field (Digital humanities (Ann Arbor, Mich.)). USA: University of Michigan Press.

Kyttä, M. (2002). Affordances of children’s environments in the context of cities, small towns, suburbs and rural villages in Finland and Belarus. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22(1), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0249.

Kyttä, M. (2004). The extent of children’s independent mobility and the number of actualized affordances as criteria for child-friendly environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(2), 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(03)00073-2.

Lackney, J. (2008). Teacher environmental competence in elementary school environments. Children Youth and Environments, 18(2), 133–159.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation (Learning in doing). . Cambridge University Press.

Lindberg, A., & Lyytinen, K. (2013). Towards a theory of affordance ecologies. In F. de Vaujany & N. Mitev (Eds.), Materiality and space. Technology, work and globalization. (pp. 41–61). Palgrave Macmillan.

Mahat, M., Bradbeer, C., Byers, T., & Imms, W. (2018). Innovative learning environments and teacher change: Defining key concepts. In LEaRN (Ed.). Melbourne.

Mattingly, D. (2016). Learning principles distilled from the research literature (pp. 1–2). Online: Columbia University.

Melo, A. T., et al. (2018). Abducting. In C. Lury, R. Fensham, A. Heller-Nicholas, S. Lammes, A. Last, & M. Michael (Eds.), Routledge handbook of interdisciplinary research methods. (pp. 90–94). Routledge.

Mulcahy, D., Cleveland, B., & Aberton, H. (2015). Learning spaces and pedagogic change: Envisioned, enacted and experienced. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 23, 575–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2015.1055128.

Newton, C. (2009). Disciplinary dilemmas: Learning spaces as a discussion between designers and educators. The Australasian Journal of Philosophy in Education, 17(2), 7–27.

OECD. (2013). Innovative learning environments (Educational Research and Innovation). . OECD Publishing.

Paniagua, A., & Istance, D. (2018). Teachers as designers of learning environments: The importance of innovative pedagogies. . OECD Publishing.

Plattner, H., Meinel, C., & Leifer, L. (2015). Design thinking research: Making design thinking foundational. . Springer.

Rivlin, L. G., & Rothenberg, M. (1975). Design implications of space use and physical arrangements in open education classes. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Environmental Design Research Association, Lawrence, Kansas, USA.

Sanders, E.B.-N., Sanders, L., & Stappers, P. J. (2012). Convivial design toolbox: Generative research for the front end of design. . BIS Publishers.

Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Introduction to communities of practice. https://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/.

Woolner, P., Clark, C., Laing, K., Thomas, U., & Tiplady, L. (2012). Changing spaces: Preparing students and teachers for a new learning environment. Children, Youth and Environments, 22(1), 52–74.

Woolner, P., Hall, E., Higgins, S., McCaughey, C., & Wall, K. (2007). A sound foundation? What we know about the impact of environments on learning and the implications for building schools for the future. Oxford Review of Education, 33(1), 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980601094693.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research. . SAGE Publications.

Young, F., Cleveland, B., & Imms, W. (2019). The affordances of innovative learning environments for deep learning: educators’ and architects’ perceptions. The Australian Educational Researcher, 47(4), 693–720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00354-y.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: semi-structured interview questions

Appendix: semi-structured interview questions

School A | School B | |

|---|---|---|

Research question | ● How can we prepare ourselves to effectively use our proposed new learning spaces? | ● How can we enhance our use of our new prototype learning space for student deep learning? |

Semi-structured interview questions – Round 1 | ● What do you find exciting or daunting about the proposed refurbishments to your school? | ● What do you find exciting or daunting about the proposed new Year 7/8 & library building? |

● What do you hope to be able to do in these spaces that you can’t do now? ● Do you expect to teach differently in the new learning spaces? | Do you expect to teach any differently in the proposed new Year 7/8 & library building? | |

● What types of spaces do you teach in now? How do you think these spaces enable or constrain your teaching? | ● What are your experiences of teaching in the prototype learning space? ● Have you taught differently than you would in other parts of the school? ● Do you find the space constraining in any way? | |

How do you think your past experience will inform your future teaching practice? | ||

Semi-structured interview questions—Round 2 | ● Were there any particular moments during the research process that raised your awareness around space as a teaching resource to enable learning activities and support you in your practice? ● What did you find difficult in the process? ● What did you find most effective in the process? ● Are there any insights, techniques, discussions from the PAR/Co-design process which you think has or will help you in transitioning to the new building/using the prototype learning space? ● What support structures were/are required to enable this transition? ● Have you (or will you) continue to trial and test practice beyond PAR process? | |

● Did you consider trialling something related to planning lessons together or Team Teaching? | ● Are you using the prototype learning space differently than prior to the first workshop in August? | |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Young, F., Tuckwell, D. & Cleveland, B. Actualising the affordances of innovative learning environments through co-creating practice change with teachers. Aust. Educ. Res. 49, 805–826 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00447-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00447-7