Abstract

Surgical training is considered to be very stressful among residents and medical students choose less often surgery for their career. Our aim was to assess the prevalence of burnout and psychological distress in residents attending surgical specialties (SS) compared to non-surgical specialties (NSS). Residents from the University of Bologna were asked to participate in an anonymous online survey. The residents completed a set of questions regarding their training schedule and three standardized questionnaires: (1) the Maslach Burnout Inventory, assessing the three dimensions of burnout: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and personal accomplishment (PA); (2) the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; (3) the Psychosomatic Problems Scale. One-hundred and ninety residents completed the survey. Overall, the prevalence of burnout was 73% in the SS group and 56.3% in the NSS group (P = 0.026). More specifically, SS reported higher levels of EE and DP compared to NSS. No significant differences between SS and NSS emerged for PA, depression, or somatic problems. The present findings indicate that burnout is more prevalent in surgical residents than in residents attending non-surgical specialties.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03668080.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During training, medical residents’ physical and emotional health are challenged by numerous stressors, including inordinately long hours, sleep deprivation, and difficulty in maintaining a work–life balance. Some studies have reported that medical residents face an increased risk of developing burnout [1, 2]. Burnout is a complex syndrome of emotional distress, which affects work performance, quality of life, and patient care [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The prevalence of burnout varies greatly among medical residents, ranging from 17.6 to 76% and surgical specialties (SS) are traditionally considered to be less “lifestyle-friendly” and characterized by high levels of work-related stress [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. The perception of this life as stressful has played a role in the mounting disinterest in pursuing a surgical career from graduating medical students. In Italy, medical graduates may choose to continue their education by applying to a residency program. Surgical trainings last between 4 and 5 years, depending on the specialty, and during this period, interns are required to perform/assist operations, work night shifts, be on call for emergencies, facing every day significant challenges. However, whether and to what extent burnout risk is actually higher in SS than in non-surgical specialties (NSS) is still unknown. Little is also known about what factors are associated with burnout between SS and NSS.

In this context, the present study has a threefold aim: (1) to measure the prevalence of burnout among a sample of Italian medical residents; (2) to contrast the prevalence of burnout and psychological distress in surgical and non-surgical residents, and (3) to identify the work-related factors associated with burnout between SS and NSS.

Methods

Participants and survey design

In October 2017, all residents attending the University of Bologna were contacted via personal emails and were asked to complete a Web-based survey. Participants were blind to the hypothesis of the study. We grounded the present work on the most recent Italian classification of medical specialties, provided by the Italian Ministerial Decree 68/2015. Respondents were classified as attending to surgical specialties (SS) or non-surgical specialties (NSS): SS included general surgery, plastic surgery, urology, vascular surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, orthopedic surgery, pediatric surgery, cardiothoracic surgery, and otolaryngology. NSS included cardiology, rheumatology, neurology, pulmonary disease, endocrinology, nuclear medicine, pediatrics, psychiatry, internal medicine, oncology, nephrology, hygiene and preventive medicine, anesthesiology, child and adolescent psychiatry, radiology, radiation oncology, infectious disease, dermatology, pathology, microbiology, hematology, gastroenterology, geriatric medicine, medical genetics, sports medicine, occupational, and environmental medicine. The study protocol was approved by the University of Bologna Ethical Committee and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier NCT03668080). Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that the survey was completely anonymous.

Outcome measures

The survey collected the following measures:

Socio-demographic characteristics and work conditions

This questionnaire was used to obtain information regarding socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender), training (specialty, year of residency), and work conditions (number of monthly night shifts, number of working hours per week).

Maslach Burnout Inventory

The prevalence of burnout was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a validated 22-item questionnaire that evaluates burnout in its three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and personal accomplishment (PA) [17]. Separated scores for each subscale were stratified into low, moderate, or high level of tertiles, as previously described [18]. Participants were considered to experience burnout symptoms if they scored in the highest tertile for EE (≥ 24 points) or DP (≥ 9 points) [7, 8, 12, 17].

Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale

The level of depressive symptoms was measured using the 20-item Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale [19]. A score ≥ 50 indicated the presence of at least mild–moderate depressive symptoms.

Psychosomatic Problems Scale

Psychosomatic symptoms were measured using the Psychosomatic Problems Scale [20]. Participants answering “often” or “always” on an item (difficulty concentrating, sleep problems, headache, stomachache, tensions, lack of appetite, feeling sad, dizziness) were coded as having a psychosomatic symptom.

Perceived time constraint

Participants indicated on a five-point Likert scale (0 = “not at all”, 4 = “completely”) whether their work schedule left them enough time for leisure activities, social interactions, and training, including lectures and research/studying.

Satisfaction with specialty

Participants answered six questions regarding the degree of satisfaction with training program, relationships with other residents and supervisors, satisfaction with career, specialty choice, and salary. Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from “not at all” to “completely”).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SD. Differences were explored by the t test and the Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi square test. Significance was defined as a P value ≤ 0.05. Since the items regarding “perceived time constraint” and “satisfaction with specialty” were highly correlated among them (Cronbach’s α = 0.73 and 0.70, respectively), they were summed to obtain a single measure. Of note, because the item “satisfaction with salary” was unrelated to the other items, it was not included for the computation of the “satisfaction with specialty” measure [21]. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were computed to evaluate the relationship between burnout scores and work-related factors. The statistical software used for all analyses was IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Of the 679 residents invited, 202 (29.8%) belonged to SS and 477 (70.2%) to NSS. Overall, 190 residents completed the survey (response rate: 28%). Surgical specialties and NSS accounted for 33.7% (n = 64) and 66.3% (n = 126) of the respondents, respectively (Table 1). The mean age was 29.1 years (range 26–35). A higher prevalence of women in NSS (67.4%) in comparison to SS (50%) was the sole difference observed among socio-demographic characteristics collected (P = 0.019).

Significant differences emerged between SS and NSS regarding the work load. Surgical residents reported working on average more hours per week (57.1 ± 13.2 vs. 45.2 ± 10.8, P < 0.001) and working more night shifts (92.1% vs. 39.7%, P < 0.001), with a higher mean of night shifts per month (2.5 ± 1.4 vs. 0.9 ± 1.2, P < 0.001) in comparison to non-surgical residents.

Prevalence of burnout and psychological distress

Considering all specialties, 118 residents (62.1%) reported either a high EE (47.9%) or a high DP (50.5%), meeting the criteria for burnout. Prevalence of burnout was higher among surgical residents (73.0%) than non-surgical (56.3%) residents (P = 0.026).

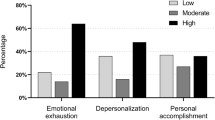

The classification of burnout dimensions scores between SS and NSS is reported in Fig. 1. There were significant differences between SS and NSS for EE (P = 0.005) and DP (P = 0.003) total scores, while no significant difference between specialty groups emerged for PA dimension.

Scores obtained for the three components of burnout (emotional exhaustion EE, depersonalization DP, personal accomplishment PA) between surgical specialties (SS) and non-surgical specialties (NSS). EE = severe ≥ 24; moderate 15–23; low ≤ 14. DP = severe ≥ 9; moderate 4–8; low ≤ 3. PA = severe ≤ 29; moderate 30–36; low ≥ 37

Considering all specialties, 15.7% of residents obtained a score higher than 50 in the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale, indicating the presence of depressive symptoms but no significant differences were observed between SS and NSS.

With respect to psychosomatic health complaints, both surgical and non-surgical residents reported that they frequently (often/always) had “difficulty concentrating” (20,1%), “difficulty sleeping” (14.3%), “suffered from headaches” (27.3%), “suffered from stomachaches” (15.3%), “felt tense” (36.3%), “had little appetite” (5.8%), “felt sad” (19.4%), and “felt giddy” (6.8%) (Fig. 2a). There were no significant differences between SS and NSS.

All the residents reported no time/limited time for lecture attendance (60.5%), research/studying (65.8%), social interactions (52.6%), and extracurricular activities (69.5%) (Fig. 2b). Surgical residents reported having less time than NSS in the “perceived time constraint” total score (P < 0.001).

The 42.6% of residents reported to be not at all/little satisfied with their training program. Unsatisfying relationships with other residents and supervisors were reported in 15.8% and 25.8% of the respondents, respectively (Fig. 2c). 8.5% of the participants reported that they were not satisfied with the specialty choice, but 58.9% would have made the same career choice. About half of the residents (50.6%) considered their salary as inadequate. On the “satisfaction with specialty” total score, no significant differences between SS and NSS were found (P = 0.054).

Factors associated with burnout

Associations among work-related factors, which significantly varied between SS and NSS, and burnout scores are reported on Table 2. Overall, the number of working hours per week and “perceived time constraint” were positively and moderately related to EE (r = 0.37 and r = 0.46, P < 0.001), while “satisfaction with specialty” was consistently related to PA scores (r = 0.37, P < 0.001).

The pattern of correlation between burnout scores and work-related factors was not different among SS and NSS, with the exception of “satisfaction with specialty” total score which was negatively and moderately related to EE in the SS group (r = − 0.48, P < 0.001), but not in the NSS group (r = − 0.13; n.s.).

Correlations between each “satisfaction with specialty” item and EE scores were further analyzed (Table 3). Surgical and non-surgical residents differed in two items referred to climate; in particular, “having good relationship with other residents” was moderately related to EE (r = − 0.50; P < 0.001) among SS but not among NSS (r = 0.08; n.s.). Similarly, “having good relationship with supervisors” was moderately related to EE (r = − 0.42; P < 0.001) among SS, but not among NSS (r = − 0.12; n.s.). The amount of salary itself was not found to be associated with burnout.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study comparing burnout between surgical and non-surgical residents and showed a higher prevalence of burnout among surgical specialties. More specifically, satisfaction with workplace relationships was associated with emotional exhaustion in the surgical residents only. Perceived time constraint and number of working hours were also found to be important.

Burnout, as described by Maslach, is a syndrome of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and a sense of low personal accomplishment that leads to decreased effectiveness at work [3, 22]. Previous studies have established that burnout is important not only because it may have a detrimental effect on the well-being of residents, but also because it has significant consequences, contributing to increased medical errors, on the health-care system and on the patients they treat [8]. In particular, surgical residents face significant challenges every day due to practice-related stress, responsibilities, and long working hours, with predictable outcomes at later stage of their career [2, 7]. A study of the American College of Surgeons shows that 40% of surgeons experience burnout, 30% symptoms of depression, and that 28% of them have a mental quality of life below that of the general population [7]. In the present sample, across different specialties types, the prevalence of burnout was 62.1%. Our results are within the range derived from previous studies on burnout in medical residents, varying between 17.6 and 86% [9, 10, 23,24,25]. However, these percentages have to be interpreted carefully and any comparison across studies cannot be definitive due to the differences that exist in every single aspect of each country’s organizational culture or in the criteria used to define burnout [2]. Similarly, our response rate (28%), although moderate compared to other surveys, was in the range for email questionnaires [26, 27].

The second aim of the study was to contrast the prevalence of burnout and psychological distress in surgical and non-surgical residents. As suggested by the literature, chronic or overwhelming stress in the absence of adequate coping skills is believed to promote psychological distress symptoms such as depression and psychosomatic disorders. In particular, depression and burnout symptoms are similar and some people may be diagnosed with burnout when they actually are depressed. For this reason, we included the Zung Depression Scale to control this aspect but, as expected, we did not find any difference between SS and NSS, confirming that depression is a more complex syndrome than burnout. Conversely, when the prevalence of burnout was compared between SS and NSS, this was found to be significantly higher in SS. Surgeons reported working more hours per week and night shifts than their colleagues attending NSS. Given the differences in terms of workload, it was not surprising that substantial differences emerged also with respect to the work–life balance. Compared to their colleagues, surgical residents reported having less time for personal and educational pursuits and interpersonal relationships. This finding corroborates previous findings indicating that surgeons have more difficulty maintaining a work–life balance than other physicians [7, 13]. Thus, the popularity of more ‘‘controllable lifestyle” specialties (e.g., anesthesiology, radiology) has increased among the current generation of medical students at the expense of SS [28, 29]. Lifestyle represents also one of the reasons which motivates residents to change their career during the residency, with the majority of them leaving SS to pursue NSS [11, 30, 31].

To develop targeted interventions to prevent burnout among residents, associations between work-related factors and burnout scores were also examined. In this sense, our research focused especially on the correlations with emotional exhaustion (EE) dimension, since EE is indicative of clinically significant burnout and the first phase of burnout development [3, 22]. Perceived time constraint and working hours were found to be positively associated with EE for both surgical and non-surgical residents. Although the work-hour restriction mandated by the European Working Time Directive (EWTD) has reported positive benefits on residents’ lifestyle, the net effects of such limitations on residents’ education continue to be debated. Some studies have raised concerns about the adverse effects on clinical training and overall quality of patient care of such restrictions [32, 33]. Others proposed to give more flexibility to the residents’ regimented call schedule, or to implement well-being programs [15, 34]. However, even though the EWTD dictates that ‘‘individual doctors can opt out”, it is not still clear where the answer lies and we believe that residents must adhere to the EWDT directive until the effects of 2014 duty hours, with special attention to SS, are examined.

Emotional exhaustion was found to be correlated also with job satisfaction. Job satisfaction is increasingly recognized as a crucial factor for performance of teams in most organizations [27, 35,36,37]. Low job satisfaction has been demonstrated to have a strong impact on many aspects, such as increased overall costs, and high turnover of personnel; however, association between job satisfaction and burnout, particularly among residents, has been poorly investigated [7, 36]. Interestingly, in our study, “satisfaction with specialty” was negatively and moderately related to EE in the SS group, but not in the NSS group. More specifically, when correlations between each “satisfaction with specialty” item and EE scores were further analyzed, the most relevant difference was found with regard to relationships with other colleagues. Understanding factors which may contribute to influence training satisfaction and in turn prevent burnout is important especially in SS where a high rate of attrition is reported [11]. In this sense, positive group dynamics and relationships with other residents may be protective of burnout, especially in SS, where communication and shared decision-making are essential to conduct high-risk operations. For this reason, directors of surgical departments should focus more on cultivating positive reciprocal relationships and on working as a team, since this may have also potential effects not only on well-being of residents but also on surgical outcomes, increasingly perceived in recent years as a function of the quality of the teamwork rather than of the single operating surgeon’s skills [36, 38,39,40,41]. Furthermore, residency program directors should be able also to meet the changing needs of their residents and expectations of their formation. As demonstrated by the correlation between EE and relationships with supervisors in SS, operative skills, traditionally based on a master–apprenticeship model, are central in surgery and what uniquely separates SS from NSS. Thus, supervising surgeons, who represent an essential component of surgical education, may influence job satisfaction and enthusiasm of their younger colleagues. At the same time, the perception of an effective surgical formation and mentorship may in turn reduce EE of residents, rendering the amount of time spent in the hospital more productive and satisfying.

However, it must be borne in mind that a good training in surgery relies not only on a motivated trainer, but also on a resident who wants to be trained. Thus, it would be worth exploring whether the association between burnout and poor satisfaction with working relationships may be due to the residents’ personality traits and coping style, their inability to maintain a work–life balance, or due to specialty-related organizational characteristics.

This study has some limitations. First, data were collected at only one institution and participating residents in this study were not representative of all Italian residents. Second, it is unknown whether residents who burned out were more prone to complete surveys due to greater interest in the topic than those who did not respond. Likewise, we do not know whether the main cause of this low but still acceptable response rate was due to a scarce interest in the topic or a lack of time. However, nonresponse bias must be always considered in any research with a survey design and/or personal disclosure of feelings. Third, we are aware that differences among subspecialties in terms of mental and/or physical burdens may lead to difference in the burnout rate between SS and NSS [42]; however, the actual sample size precludes any more detailed analysis. We also recognize that it is impossible to fully understand the direction of some causal–effect relationships between work-related factors and burnout; however, we believe that a lower EE is largely related to the more intangible benefits of positive workplace climates and a constructive teamwork, which is essential to the culture of well-being, especially in surgical residents.

Conclusions

Taken together, the present findings suggest that burnout syndrome is not a negligible phenomenon among surgical residents. In particular, specialty programs should enhance medical students’ and residents’ awareness of the risk of stress associated with their career choice and provide them with training in the management of workplace relationships.

References

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ et al (2016) Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 388:2272–2281

Prins JT, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Tubben BJ et al (2007) Burnout in medical residents: a review. Med Educ 41:788–800

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP (2001) Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 52:397–422

Brazeau CMLR, Schroeder R, Rovi S et al (2010) Relationships between medical student burnout, empathy, and professionalism climate. Acad Med 85:S33–S36

Kuerer HM, Eberlein TJ, Pollock RE et al (2007) Career satisfaction, practice patterns and burnout among surgical oncologists: report on the quality of life of members of the Society of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol 14:3043–3053

Green A, Duthie HL, Young HL et al (1990) Stress in surgeons. Br J Surg 77:1154–1158

Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ et al (2009) Burnout and career satisfaction among american surgeons. Ann Surg 250:463–470

Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G et al (2010) Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg 251:995–1000

Garza JA, Schneider KM, Promecene P et al (2004) Burnout in residency: statewide study. South Med J 97:1171–1173

Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE et al (2002) Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 136:358–367

Yeo H, Bucholz E, Ann Sosa J et al (2010) A national study of attrition in general surgery training: which residents leave and where do they go? Ann Surg 252:529–534

Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D et al (2014) Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med 89:443–451

Elmore LC, Jeffe DB, Jin L et al (2016) National survey of burnout among US general surgery residents. J Am Coll Surg 223:440–451

Lebares CC, Guvva EV, Ascher NL et al (2018) Burnout and stress among US surgery residents: psychological distress and resilience. J Am Coll Surg 226:80–90

Yoo PS, Tackett JJ, Maxfield MW et al (2017) Personal and professional well-being of surgical residents in New England. J Am Coll Surg 224:1015–1019

Chati R, Huet E, Grimberg L et al (2017) Factors associated with burnout among French digestive surgeons in training: results of a national survey on 328 residents and fellows. Am J Surg 213:754–762

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP et al (1996) Maslach Burnout Inventory manual, 3rd edn. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

Sirigatti S, Stefanile C (1993) MBI—Maslach Burnout Inventory. Adattamento e taratura per l’Italia. In: Firenze, Organizzazioni speciali, pp 33–42

Zung WWK (1965) A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 12:63–70

Hagquist C (2008) Psychometric properties of the PsychoSomatic Problems scale: a Rasch analysis on adolescent data. Soc Indic Res 86:511–523

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH (1978) Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill, New York

Rafferty JP, Lemkau JP, Purdy RR et al (1986) Validity of the Maslach burnout inventory for family practice physicians. J Clin Psychol 42:488–492

Gelfand DV, Podnos YD, Carmichael JC et al (2004) Effect of the 80-hour workweek on resident burnout. Arch Surg 139:933–940

Bertges Yost W, Eshelman A, Raoufi M et al (2005) A national study of burnout among American transplant surgeons. Transplant Proc 37:1399–1401

Rodrigues H, Cobucci R, Oliveira A et al (2018) Burnout syndrome among medical residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 13:e0206840

Kaplowitz M, Hadlock T, Levine R (2004) A comparison of web and mail response rates. Public Opin Q 68:94–101

Tschuor C, Raptis DA, Morf MC et al (2014) Job satisfaction among chairs of surgery from Europe and North America. Surgery 156:1069–1077

Bland KI, Isaacs G (2002) Contemporary trends in student selection of medical specialties: the potential impact on general surgery. Arch Surg 137:259–267

Dorsey ER, Jarjoura D, Rutecki GW (2003) Influence of controllable lifestyle on recent trends in specialty choice by US medical students. JAMA 290:1173–1178 (Erratum in: JAMA. 2003 26;290:2666)

Jarecky RK, Schwartz RW, Haley JV et al (1991) Stability of medical specialty selection at the University of Kentucky. Acad Med 66:756–761

Schwartz RW, Haley JV, Williams C et al (1990) The controllable lifestyle factor and students’ attitudes about specialty selection. Acad Med 65:207–210

Goitein L, Shanafelt TD, Wipf JE et al (2005) The effects of work-hour limitations on resident well-being, patient care, and education in an internal medicine residency program. Arch Intern Med 165:2601–2606

O’Gallagher MK, Lewis G, Mercieca K et al (2013) The impact of the European Working Time Regulations on Ophthalmic Specialist Training—a national trainee survey. Int J Surg 11:837–840

Riall TS, Teiman J, Chang M et al (2017) Maintaining the fire but avoiding burnout: implementation and evaluation of a resident well-being program. J Am Coll Surg 226:369–379

Raptis DA, Schlegel A, Tschuor C et al (2012) Job satisfaction among young board-certified surgeons at academic centers in Europe and North America. Ann Surg 256:796–805

von Websky MW, Oberkofler CE, Rufibach K et al (2012) Trainee satisfaction in surgery residency programs: modern management tools ensure trainee motivation and success. Surgery 152:794–801

Spector PE (1997) Job satisfaction: application, assessment, cause, and consequences. Sage, Beverly Hills

Johns MM, Ossoff RH (2005) Burnout in academic chairs of otolaryngology: head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope 115:2056–2061

Appelbaum NP, Lee N, Amendola M, Dodson K, Kaplan B (2019) Surgical resident burnout and job satisfaction: the role of workplace climate and perceived support. J Surg Res 234:20–25

Vincent C, Moorthy K, Sarker SK et al (2004) Systems approaches to surgical quality and safety: from concept to measurement. Ann Surg 239:475–482

Grogan EL, Stiles RA, France DJ et al (2004) The impact of aviation-based teamwork training on the attitudes of health-care professionals. J Am Coll Surg 199:843–848

Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR et al (2018) Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA 320:1114–1130

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express appreciation to the residents who participated in the study.

Funding

This study was not supported by any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. Institutional review board gave ethical approval to perform this study.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Serenari, M., Cucchetti, A., Russo, P.M. et al. Burnout and psychological distress between surgical and non-surgical residents. Updates Surg 71, 323–330 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-019-00653-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-019-00653-0