Abstract

Study objective

The objective of this study was to prospectively analyze the risks and benefits of total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) compared with total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) and the effects of learning curve on them over 4 years (March 2010–April 2014).

Design

It was a prospective randomized study.

Setting

The study was conducted in Delhi government hospital which had no staff with previous experience of advanced laparoscopic surgeries.

Patients

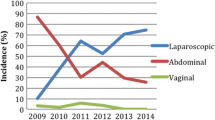

Two hundred fifty patients were operated on for benign gynecological conditions (35–65 years). The numbers of cases operated laparoscopically were as follows—22 in 2010, 25 in 2011, 32 in 2012, and 46 in 2013. Equal number. of patients operated by open surgery were taken in the study during the same time period.

Results

Two hundred fifty cases were operated since March 2010, by either laparoscopic or open surgery. Incidence of major complications was—1.6 % for TLH compared to 4 % in TAH. After the first year of surgery, this incidence has fallen to 0 % in subsequent years in TLH group. The incidence of minor complications declined from 14 to 4.5 % in the third year of study. Total rate of conversion to laparotomy was 9.7 %, which again had a significant decline after the first year. TLH also clearly showed superior benefits of less intraoperative blood loss, early postoperative ambulance, and shorter period of hospital stay in comparison with TAH.

Conclusion

The study has led us to conclude that TLH is a safe, effective, and reproducible technique after the completion of a period of training necessary to standardize the procedure. This approach must be established in our real, day-to-day clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Minimal access surgery as a modality of treatment for various gynecological conditions is rapidly gaining grounds in the recent years. Although laparoscopic surgeries are widely performed in private setups, very few government hospitals and institutions have been successful in establishing this advanced mode of surgery in their day-to-day practice. Problem of maintenance of costly equipment, excess patient load, and fear of complications are the main constraints in the minds of surgeons, preventing them from undertaking this initiative. In this study, we have evaluated the safety and benefits of this mode of surgery within the constraints of a government setup.

Materials and Methods

This is a prospective study of 250 patients aged 35–65 years, who underwent hysterectomies indicated for various benign pathologies during March 2010–April 2014. The Ethics Committee of Deen Dayal Upadhyay Hospital approved the study protocol. 125 patients underwent TAH, and another 125 underwent TLH. Patients had given their written informed consent to undergo either laparoscopic hysterectomy or abdominal hysterectomy. Both groups had similar indications for hysterectomy, similar body mass index (31), and parities, and method was selected by closed envelope method of randomization. Patients were followed-up until 6 months after surgery.

Pre-operative Preparations

In both groups after pre-anesthetic checkup and fitness, pre-op antibiotics were given as per routine protocol. Instruments and method followed for abdominal hysterectomy were those of standard routine practice.

For laparoscopic hysterectomy, all patients underwent pre-operative bowel preparations with polyethylene glycol dissolved in 1 l of water a day prior to surgery. A combination of regional and general anesthesia was used.

Instruments used included bipolar forceps, harmonic ace (5 mm) with generator, two endoscopic graspers, two needle holders, a uterine manipulator (the Mangeshkar’s uterine manipulator), 10 mm-0° laparoscope, and three-chip camera with light source (Fig. 1).

A team of two surgeons performed the laparoscopic hysterectomies in the initial year and later both of them formed their own teams.

Patient was placed in modified lithotomy position with bolster below pelvis at the level of anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 2). Pre-operative catheterization was done in all patients, and nasogastric tube was inserted under anesthesia. Mangeshkar’s uterine manipulator was inserted in all cases of TLH after p/v examination under anesthesia. Assistant on the vaginal side handled this manipulator.

Main surgeon stood on the left side of the patient, while the first assistant stood on the right side of the patient.

The assistant holding the camera stood on the left side besides the main surgeon. Abdominal entry was made at the umbilical site by direct 10-mm trocar. In cases of previous surgical scar, Veress needle was inserted through Palmer’s point to create pneumoperitoneum. Three or four ancillary 5-mm trocars were placed under direct vision lateral to the rectus abdominis muscle 2 cm above and 2 cm medial to anterior superior iliac spine on both sides. In addition, a 5-mm trocar was placed approximately 6–8 cm above and parallel to lower trocar.

After an accurate abdomino-pelvic inspection, lysis of any adhesions was performed. Left-sided round ligament was then identified and kept stretched with the help of vaginal assistant holding uterine manipulator. It was coagulated with bipolar forceps and cut using Harmonic ace scalpel around 1 cm lateral to its attachment to uterus, the chief surgeon holding these instruments in left and right hands, respectively.

Next, the infundibulopelvic ligament (in case ovaries were removed) or the tubo-ovarian structure (in case ovaries were conserved) of left side was identified. The assistant on the right side helped in holding and stabilizing the ovary. The ligament was then first coagulated with bipolar forceps and then cut with harmonic scalpel. The use of two energy sources helped in ensuring perfect hemostasis. Same procedure was repeated on the right side.

Medial cut end of round ligament was held with grasper, and anterior and posterior leaves of broad ligament were separated with two blades of harmonic ace. The vesicouterine fold was clearly identified. The fold was then cut with harmonic scalpel starting from left round ligament to the right round ligament staying close to the uterus. The bladder was then pushed down using the blunt side of a traumatic grasper at the center against the counter pressure of the cup of uterine manipulator. Few fibers of bladder pillar were then cut again using harmonic ace. After nicely pushing the bladder down, the whole bundle of uterine vessels was coagulated with bipolar grasper at the level of internal cervical oss, without skeletonizing the uterine artery. Pushing cephalad with the uterine manipulator helped to move the uterine vessels away from the ureter. Complete desiccation of vessels could be assessed visually by observing the bubbles coming and going during this process; when the bubbles stopped forming, the vessel was desiccated and safe to transect with harmonic scalpel. After transection, the uterine stump falls laterally, and further dissection is performed medial to stump down the cup by coagulating and cutting.

Vaginal fornices were identified while pushing the manipulator cephalad. The upper margin of the cup of uterine manipulator presented a bulge, which helped to identify cervico-vaginal junction. The metallic active blade of harmonic scalpel was used to make a cut on anterior aspect. The cut was then extended laterally on both sides, leaving the lateral attachments. Uterus was then acutely antiverted by vaginal assistant. First, a small nick was given between and just above the level of attachment of two uterosacral ligaments, using metallic active blade of harmonic scalpel. The cut was then completed laterally to complete the procedure. Uterus was then pulled into vagina and taken out. In cases of large uteri or limited vaginal access, wedge morcellation was also performed. Finally, the vaginal vault was sutured laparoscopically or vaginally, and then pelvis was checked in order to ensure hemostasis and pelvic irrigation performed thus removing blood clots.

Parameters were Evaluated in the Two Groups

A statistical analysis of the data was performed using student’s t test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Operating time The beginning of the operation was calculated as the moment of umbilical incision and introduction of the Veress needle for laparoscopic hysterectomy and as the moment of the cutaneous incision for the abdominal technique. Cutaneous suture was considered at the end of the operation in both cases.

Amount of blood loss The amount of blood loss during laparoscopic hysterectomy was calculated as the difference between the volume of liquid introduced into the pelvic cavity for irrigation purpose and the volume of liquid aspirated during the operation. Blood loss during TAH was estimated by calculating the blood volume of the suction machine during surgery and by weighing swabs used during surgery.

Duration of post-operative Ambulance It was defined as duration between the end of surgery and the ability of patient to stand and walk.

Major complications during surgery These were defined as complications requiring re-surgery on conversion to laparotomy in case of laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Minor Ccmplications These were also compared between the two groups.

Number of conversions to abdominal hysterectomy It was studied in the TLH group.

Results

Indications of Surgery

Most common indications for hysterectomy were uterine fibroid followed by abnormal uterine bleeding both in TLH and TAH groups. Other indications were adenomyosis and endometrial hyperplasia (Table 1). Timothy et al. [1] reported that the most common indication of TLH was adenomyosis, while uterine fibroid was the commonest indication for TAH.

Duration of Surgery

The average time required in TLH in the first year after starting surgery was 147.37 min compared to 84.84 min in TAH. This time difference gradually decreased in subsequent years, with average of 95.6 min in the fourth year in the TLH group. The differences in the durations of surgery between the two groups over 4 years were not statistically significant (Fig. 3).

Amount of Blood Loss

Average intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower in TLH as opposed to TAH (Table 2). Similar results were also observed by Baek et al. [2] and Sutasanasuang [3].

Patients who underwent TLH had less intensive postoperative pain than did the patients in the TAH group.

Duration of Hospital Stay

The average durations of hospital stay in TAH group were 5.68 and 3.58 days in TLH (Table 3). This shorter hospital stay in cases of laparoscopic was found to be statistically significant. Baek et al. [2], observed that, in a study on 100 cases, the length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for TLH than for TAH. Similar results were also reported by Persson et al. [4] and Johnson et al. [5].

Postoperative Ambulance Time

In the TLH group, the postoperative ambulance time was less than in TAH group and was statistically significant (Table 4).

Major Complications

Incidence of major complications in TLH was 1.6 % (2 in 125) compared to 4 % (5 in 125) in TAH group: one ureterovaginal fistula, and one bladder injury occurring in the first year of starting surgery in TLH group. In subsequent years, there was no major complication (Table 5). This is attributed to the learning curve associated with laparoscopic surgery. In the first case of ureterovaginal fistula, the patient presented with vaginal urinary leak on day 9. This was due to thermal damage caused by the use of energy source while desiccating uterine artery. Patient was referred to urosurgeon and successfully managed by performing laparotomy with ureteric reimplantation. Second case of bladder injury caused during dissection of uterovesical fold of peritoneum was detected intra-op only and repair done by converting to laparotomy. Five cases of major complications in TAH group were recorded: one case of large bowel injury, while performing adhesiolysis; two cases of bladder injury; and two cases of burst abdomen.

Minor Complications

Incidence of minor complications in TLH group was 7.1 % (9 out of 125) compared to 9.7 % in TAH group (12 out of 125). Incidence was 14 % (3 out of 22) in the first year and decreased in subsequent years to 4.3 % (2 out of 46) in the last year in TLH group. Most of these were secondary hemorrhage from the vault, urinary tract infection, surgical emphysema, hematoma at ancillary port site, and severe gastritis.

Converts to Laparotomy

Total rate of conversion to laparotomy was 9.6 % (12 out of 125), which again had a significant decline after the first year (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The potential benefits and risks of laparoscopic hysterectomy have been widely reported since the first total laparoscopic hysterectomy was performed by Harry Reich in 1989. In some randomized controlled studies, it was concluded that the duration of TLH was significantly longer than that of TAH, for example, Perino et al. [6] and Sutasanasuang [3]. In our study, this time difference was not found to be significant. In another previous study by Siren and Sjoberg [7], 100 successive laparoscopic hysterectomies performed by a senior gynecologist were assessed in order to evaluate the learning curve. It was found that the duration of surgery decreased from an average of 180 min for the first ten operations to an average of 75 min for the last 20. In a systematic review on total 3643 participants by Johnson et al. [5], it was observed that there were more urinary tract injuries with laparoscopic than with abdominal hysterectomy, but no other intraoperative visceral injuries showed a significant difference between surgical approaches. In our study, there were two major complications in TLH group, and both were urinary tract injuries in the initial year. In subsequent years with more precision and experience, we were successful in avoiding these complications, thus emphasizing the importance of learning curve. Previously published papers reported an incidence of serious complications of 3.5–5 per 1000 for advanced laparoscopic procedures, for example, Chapron et al. [8]. However, these results, obtained by experts in centers with considerable experience, are not representative of general situation.

Minimally invasive surgery has known advantages over open surgery as observed in this study and in various earlier studies. Still, the uptake of this mode of surgery among gynecological surgeons has been slow.

It has been slower in government setups, due to various constraints in arranging equipment and fear of complications. We want to share the fact that our method of performing surgery has resulted in good outcomes and significantly less complications. The surgeons must realize that in this mode of surgery, the learning curve matters a lot, and so a few initial complications must not deter them. Instead, they must try to analyze themselves after operating each patient and keep on improving their technique and skills and continue to perform more surgeries. We want to highlight a few recommendations for a successful start, which we have learned during this time period:

-

Start only after hands-on training to learn hand–eye coordination. Keep practicing on pelvi-trainer when you are not performing surgeries.

-

Learn to use both hands from the beginning as you do in open surgery.

-

Arrange the equipment and be familiar with its function before starting the surgery.

-

The operating surgeon must know what assistants and staff nurse are supposed to do, must guide them, and supervise them at every step.

-

Take the same team for a number of cases in the beginning stages till you gain confidence.

-

On the day before the surgery, check the functioning of all equipments from inlet to end result. There should be a standby for all vital equipment.

-

After finishing each case, proper cleaning of instruments, handling with care, and proper packaging must all be ensured by the operating surgeon.

-

Be aware of the dangers of energy devices when they are used near the bladder and ureter. No energy source is 100 % safe. So, work near the uterus or vagina leaving a margin of tissue.

-

Avoid tendency to drift laterally with the instruments and properly utilize traction and counter traction of uterus.

-

While performing closure of vaginal cuff and anchoring it to the uterosacral ligament, take care to avoid stitch lateral to cuff margin.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study shows that total laparoscopic hysterectomy can be performed within reasonable time limits even by surgeons with no previous experience of advanced laparoscopic surgeries, provided proper technique is followed and the same team initially does a number of cases. It clearly showed superior benefits of less intraoperative blood loss, early postoperative ambulance, less postoperative pain, and shorter hospital stay. It was also shown to be equally safe as total abdominal hysterectomy. Thus, total laparoscopic hysterectomy is a safe, effective, and reproducible technique after completion of the period of training necessary to standardize the procedure. This approach must be established in our real, day-to-day clinical practice.

References

Ren TLC, Kannaiah K. A review of clinical benefits of total laparoscopic hysterectomy and total abdominal hysterectomy. Sungai Petani: Hospital sultan Abdul Halim; 2010.

Baek JW, Gong DS, Lee GH. A comparative study of total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) and total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH). Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(6):1490–6.

Sutasanasuang S. Laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy: a retrospective comparative study. J Med Assoc Thail. 2011;94(1):8–16.

Persson P, Wijma K, Hammar M, et al. Psychological wellbeing after laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy—a randomised controlled multicentre study. BJOG. 2006;113(9):1023–30.

Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, et al. Methods of hysterectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2005;330:1478.

Perino A, Cucinella G, Venezia R, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy: an assessment of the learning curve in a prospective randomized study. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(12):2996–9.

Siren PH, Sjoberg J. Evaluation and the learning curve of the first 100 laparoscopic hysterectomies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74:638–41.

Chaperon C, Querleu D, Bruhat M, et al. Surgical complications of diagnostic and operative gynecological laparoscopy: a series of 29,966 cases. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:867–72.

Compliance with Ethical Requirements and Conflict of Interest

The study was conducted in Deen Dayal Upadhyay Hospital (DDUH, Delhi Government) and financed by the institution. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before being included in the study. The Ethics Committee of DDUH approved the study protocol. The procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the ethics committee and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Poonam Agarwal, Neeta Bindal, and Reena Yadav declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Poonam Agarwal is CMO-NFSG in DDU Hospital, New Delhi, India; Neeta Bindal is SAG in DDU Hospital, New Delhi, India; Reena Yadav is SR in ESI Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Agarwal, P., Bindal, N. & Yadav, R. Risks and Benefits of Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy and the Effect of Learning Curve on Them. J Obstet Gynecol India 66, 379–384 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-015-0706-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-015-0706-9