Abstract

The influx of effluents from industrial area into the Alaro River in Ibadan has made the investigation of the sediment quality of the river an important environmental issue for discussion. The objective of this study was to determine the concentrations of toxic heavy metals in surface sediment of the river in order to evaluate the impact of the effluent and spatial distribution of the metals downstream. pH, total organic carbon and grain-sized particles of the sediment samples were determined according to standard methods of analysis, while heavy metal concentrations were determined by AAS. Linear least square regression (LLSR) model was employed to describe the distribution pattern of heavy metals along the river network. Hierarchical cluster analysis was applied to locate the heavy metals contamination source and interpret the association between the metal concentrations upstream and downstream, which were found to be significantly different (p = 0.05) The concentrations of Ni, Zn, Cr, Co, Cu, Cd and Pb in downstream sediments were 7.74 ± 0.97, 19.5 ± 4.6, 5.78 ± 0.47, 9.6 ± 1.6. 7.36 ± 0.61, 0.47 ± 0.03 and 7.76 ± 0.80 mg/kg, respectively. The enrichment factor (EF > 1.5) and pollution load index (PLI > 1.0.) showed that the sediment was contaminated with these heavy metals. The toxicity estimation carried out suggested that the sediment was slightly toxic. Metal distribution as shown by LLSR was such that the concentration decreased with distance downstream with R2 ranging from 0.8810 to 0.9990. The LLSR models obtained are useful to predict the metal concentrations based on the known distance of the river.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The incidence of surface water contamination with toxic and persistent heavy metals is increasing worldwide because of the ever increasing industrialization in most countries (Ahmed and Ahmaruzzaman 2016; Tripathee et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2017). In most industrialized areas of the developing countries such as Nigeria, surface waters that receive industrial discharges directly have been rendered unfit for beneficial purposes and aquatic organism habitation (Chandran et al. 2016; du Plessis 2017; Khatri et al. 2016). The main receptacles in surface waters for contaminants from industrial discharges are river sediment (He et al. 2016; Li et al. 2016; Nguyen et al. 2016; Peng et al. 2017). Several cases of fish death have been reported due to invasion of river sediment with toxic metals released into river systems. One of such is the case of the State of Minas in Brazil when metal-rich effluent was released to the dam breach in Mariana (Fernandes et al. 2016). Some industries whose production processes are unregulated and engage in improper discharge of untreated or partially treated effluent to river system due to inefficient or lack of wastewater treatment plants have been reported. The industries include oil refineries, paper manufacturing, textile, food and beverages (Patra et al. 2016). The environmental conditions of a river system particularly sediment change with the invasion of uncontrolled contaminants such as heavy metals. It is pertinent to investigate the distribution pattern of such contaminant in the aquatic environment in order to ascertain the extent of contamination. Several studies have focused only on heavy metal contamination in river water, such as the Pearl River in China (Zhen et al. 2016), Karnaphuli River in Bangladesh (Ali et al. 2016), Ona River and Olosun River in Nigeria (Ipeaiyeda and Onianwa 2016). The few attempts made on Nigerian rivers were to determine only the heavy metal concentrations in major river water, leaving out dearth of information on small river sediment particularly the dispersion of heavy metals in river system that is of importance to the country. Small and notable rivers play a significant role in regional economy development and ecological robustness.

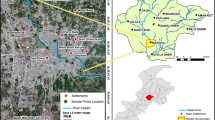

The Alaro River is notable in Nigeria and is located on the northeast part of Ibadan with water depth of less than 10 meters. The river originates from Ijokodo and flows south east through Oluyole industrial estate (Fig. 1) into the Ona River along Ibadan–Lagos expressway. Near the river channel particularly downstream of Oluyole industrial estate are hotels, camping sites, restaurants, entertainment or events centers and schools. Considering the ongoing activities around the Alaro River, it indeed serves the dual purpose of providing recreational facility that affects social life of people and contributing to regional water supply to small-scale industries. As important as the river is, it still receives effluent discharges from industries, which result in pollutants deposition in the sediment. The categories of industries concentrated in the estate include food and beverage, pulp and paper, chemical and pharmaceuticals and publishing industries, which lack efficient effluent treatment plants. Studies have shown that these industries contribute to increased concentration of heavy metals in river sediment. For instance, the heavy metal pollution derived from the Magdalena River in Columbia was a clear consequence of direct discharges from coal mining and oil transportation sources (Tejeda-Benitez et al. 2016). Kumarkhali textile in Kushtia industrial area of Bangladesh contaminated Goral River sediment with toxic heavy metals (Islam et al. 2015). The presence of heavy metals in Guadiamar River in Spain was adduced to wastewater from pharmaceutical and textile industries (Garrido et al. 2016).

Pollutant discharges from industries can lead to metal bioaccumulation in fishes and prolonged release of heavy metals from contaminated sediment into surface water (Bian et al. 2016; Pourabadehei and Mulligan 2016). Considering the relevance of the Alaro River as it feeds the Ona River, which is the main source of water supply to the populace in Ibadan, it is important to investigate the impact of heavy metal pollution arising from the industries in the river sediment. The surface water quality of the Alaro River had been previously reported (Ipeaiyeda and Onianwa 2011) leaving out information on the sediment component of the river system. In this study, the objective was to investigate the impact and distribution of some toxic heavy metals from industrial discharges in Alaro River sediment. The pollution status of the river was assessed through the enrichment factor and pollution load index.

Materials and methods

Study design and sediment sampling

The sampling locations were purposively selected. The upstream, downstream and junction of the effluent channel to the river were selected for sediment sampling. One location, designated as JN (0 m), was selected at the junction where the combined industrial effluent collectively flows into the Alaro River. Two locations were selected upstream to serve as controls and were denoted as U1 (150 m) and U2 (300 m). Five sampling points were located downstream of the river channel and were depicted as D1 to D5 at about 150 m away from each other. There was no sampling point selected along the combined effluent channel because the floor is a concrete and contains no sediment. The sediment samples were collected monthly within a year to cover both wet and dry seasons. A total of seventy-eight sediment samples were collected with a stainless Van Veen grab sampler, placed in polyethylene bags and stored in an ice chest.

Sediment analysis

In the laboratory, the samples were air-dried, ground into fine powder, sieved through 0.5-mm screen and placed in polyethylene bags until the analysis period. The analysis methods were carried out according to the international standard ISO procedures. Sediment samples were digested with nitric acid based on protocols highlighted by Office Fe´de´ral de la Protection de l’Environment (Hurlimann 1981). The nitric acid digestion of 5.0 g of sediment samples with 50 mL of 3 M HNO3 in a covered glass bottle was performed in a boiling water bath for 2 h. The analytical procedure was monitored throughout the analysis using the standard reference material (ST-SD-3) obtained from Canada Centre for Mineral and Energy Technology (CANMET, Canada). A blank and standard solutions were analyzed periodically. The concentrations of Ni, Zn, Cr, Co, Cu, Cd and Pb in the digests were determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry.

Particle size analysis was conducted using the pipet and hydrometer method involving the dispersion of the samples in 5% sodium hexametaphosphate after digestion of organic matter content with 30% hydrogen peroxide (Loveland et al. 2000). Total organic carbon (TOC) was determined using Walkley and Black method (Pansu and Gautheyrou 2007). This method involves oxidation of organic matter with excess amount of dichromate (K2Cr2O7) in acidic medium and back titration of excess dichromate with standard Fe2SO4 solution.

Assessment of sediment pollution load

The pollution level of sediment with heavy metals was determined using the enrichment factor (EF) and pollution load index (PLI). The enrichment factor was calculated using the equation, Cm/Cn, being the ratio of the concentration of the metal of interest in the analyzed sediment (Cm) to the corresponding background concentration (Cn) of the metal (Hakanson 1980). The metal in the sediment is predominantly of natural origin if EF value of 1.0 is obtained. If EF > 1.5 indicates enrichment by anthropogenic impacts (Hakima et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2016). The pollution index (PLI) was calculated using the expression PLI = (EF1 × EF2 × EF3… × EFn)1/n where n is the number of elements determined in the samples. PLI value > 1 indicates pollution of the sediment quality, while PLI value < 1 implies that the pollution is not occurring (Tomlinson et al. 1980).

The percent recovery capacity (RC) of the river sediment from metal pollution load was calculated using the expression RC = [(Co − C1)/Co] × 100 (Knox et al. 2016), with Co as the concentration of metal at the last downstream reach of the river and C1 as the corresponding concentration upstream where there is no effluent discharge.

Estimation of toxicity

The environmental toxicity of downstream sediment was evaluated using the mean effects range-medium expression quotient (mERMq) = \(1/N\;\sum\nolimits_{i}^{n} {Ci/ERMi}\) (Long 2006). The variable N is the amount of toxic metals considered in the evaluation, Ci is the main concentration of the toxic metal in the sediment sample, and ERMi is the concentration estimated for a particular metal above which toxic effect is expected.

Data analysis

The relationship between the studied metals was determined using Pearson correlation (p = 0.01 and 0.05). The cluster analysis was adopted to identify the pollution source that might be either anthropogenic or natural. The average metal concentrations of upstream and downstream were compared using Waller–Duncan test. The distribution pattern along the river network was explained using a stepwise regression procedure, which relates the metal concentrations with distances along the river channel (Nour 1972).

Results and discussion

Sediment quality of Alaro River

Contamination of sediments with toxic metals is commonly related to particle grain size. The sediment samples of Alaro River were majorly composed of fine grained sand with average contents varying from 86.1 ± 9.5% to 92.9 ± 1.6% (Table 1). This implies that the hydromorphic distribution patterns of contaminants are supported in the fine sandy fraction of the river sediment (El Azhari et al. 2016). In rivers, sandy fraction often offers a favorable condition for remobilization of accumulated metals. Toxic metals accumulated in sand readily travel long distance as suspended sediments remobilize particularly with little disturbance of the bottom sediment (Salomons and Förstner 2012).

The pH values of the sediments ranged from 6.8 to 7.5 (Table 1). The effluent discharges received by the river at the junction only raised the background pH of the sediment by 7.6%. Sediment pH values at upstream were not significantly different from those of downstream. This indicates the fact that the effluent has not significantly impacted the sediment pH. When pH value increases, most heavy metals are removed from solution by precipitation process and adsorbed on the bottom sediment because of the production of hydroxide (Li et al. 2016). The pH downstream was 7.3 ± 0.1, which was higher than 6.6 ± 1.2 for downstream pH. This is an indication that the concentrations of metals would possibly be more pronounced in downstream sediment than upstream sediment.

Nickel concentration in the downstream sediment was elevated by effluent inputs. This was reasoned from the high concentration of nickel in the downstream sediment in comparison with the upstream sediment. Nickel level at the discharge point was 8.5 ± 6.9 mg/kg, which was much higher than the upstream nickel level of 7.74 ± 0.97 mg/kg (Table 1). Concentrations of nickel in sediment samples after the discharge point generally increased as distance increased downstream (Fig. 2). There were high levels of other potentially toxic metals (Zn, Cr, Co, Cd and Pb) in downstream sediments. The increased concentration is traceable to the combined industrial wastewater that flows into the Alaro River with evidence of high metal concentrations at the discharge point as shown in Table 1. Regarding the metal concentrations at downstream location, 19.5 ± 4.6 mg/kg (Zn), 5.78 ± 0.47 mg/kg (Cr), 9.6 ± 1.6 mg/kg (Co), 7.36 ± 0.61 mg/kg (Cu), 0.47 ± 0.03 mg/kg (Cd) and 7.76 ± 0.80 mg/kg (Pb) were obtained (Table 1). These concentrations were significantly higher than the corresponding concentrations in upstream sediments.

The majority of the metals (Cr/Ni, Co/Ni, Cu/Co, Cd/Co, Cd/Cu and Pb/Cd) showed significant correlations indicating similar origin of the metals (Table 2). The uptake of toxic metals by sediments is influenced by total organic matter (TOM) which potentially binds with the metals (Xu et al. 2016). The organic matter as well as sand-sized particle acts as an efficient scavenger for toxic metals in sediments (Venkatramanan et al. 2015). It seems the concentrations of all toxic metals were not solely controlled by organic matter considering the correlation values of TOM with metal concentrations. The association of organic matter with copper was much compared with other metals analyzed in the samples. The organic matter content is strongly correlated with Cu (r = 0.521, p = 0.01; Table 2). Poor correlation of organic matter with other metals is an indication that sediment is not the major heavy metals transporter in the Alaro River ecosystem.

Comparison of metal concentrations with sediment quality guidelines

The comparison of metal concentrations in river sediments with sediment quality guidelines (SQGs) is important for determining the likelihood that such sediments would be toxic to aquatic and sediment-dwelling organisms. Each country is encouraged to develop SQGs by SETAC Sediment Advisory Groups for managing contaminated sediments. SETAC is a Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, whose mission is not implemented in Nigeria as SQGs have not yet been developed. This necessitated the comparison of data from this study with the Canadian and Ontario SQGs, and toxicity reference value set by US EPA (Table 3). The levels of Ni, Cr, Zn, Co Cu, Cd and Pb in downstream sediments were below the sediment quality guidelines. To have metal concentrations in the sediment not exceeding SQG does not suggest non-toxic effect to benthic and other sediment-dwelling organisms. The actual SQGs are formulated from locations where mixtures of toxic contaminants exist. Therefore, biological responses at these locations are certainly affected by multiple toxicants which were not considered in this study. The occurrence of SQGs does not take into consideration the bioavailable fraction of the toxic heavy metals. This has been identified as one of the limitations of SQGs (Burton 2002). Hence, other approaches of assessing the sediment contamination such as EF, PLI and mERMq are important and can be explored.

Quantification of sediment contamination

The highest EF value of 2.04 was observed for Nickel, and the lowest EF of 1.36 for Zn (Table 1). The pollution load index (PLI) for the sediment was 1.74, which indicates that the Alaro River sediment is impacted with Ni, Zn Cr, Co, Cu and Pb whose EF values > 1. This implies that a significant level of each heavy metal is obtained from non-crustal materials portraying anthropogenic discharges into the river (Zhang et al. 2017). Upon contamination by these metals, recovery capacities ranging from 34.0 to 58.7% from metal pollution load of effluent discharges were obtained (Table 1).

The mERMq is an index that takes into consideration not only the concentration of target toxic metal in the sediment sample, but also toxicological data realized in the laboratory using model organisms under controlled experimental conditions as mentioned in the literature (Long and Morgan 1990). Regarding values of ERMi, the only available data for Ni, Zn, Cr, Cu and Cd are 16, 110, 26, 16, 0.6 and 31, respectively (US EPA 1999). The range of 0–0.1, 0.1–0.5, 0.5–1.5 and > 1.5 is stipulated as mERMq values indicating categories of non-toxic, slightly toxic, moderately toxic and highly toxic, respectively. Each range of values of mERMq shows a corresponding probability of being toxic by 9%, 21%, 49% and 76%, respectively (Rodríguez-Barranco et al. 2013). The mERMq value for the sediments collected in this study was evaluated using the concentrations of Ni, Z, Cr, Cu, Cd and Pb since Co has no toxicity reference value. The mERMq of 0.40 was obtained for the sediment of Alaro River indicating that the sediment is slightly toxic.

Seasonal variation and distribution pattern of heavy metals in sediment

The high input of heavy metals was observed in dry season compared to wet season (Fig. 2). The seasonal variations of heavy metal contamination of the Alaro River particularly for Cd, Cr, Cu and Zn were similar to that of Liaohe River of Northeast China (Wang et al. 2017) and Subarnarekha River of India (Banerjee et al. 2016). Hierarchical cluster analysis was employed to describe the difference in metal concentration at different sampling locations. Figure 3 reveals three main groups of sediment samples. The grouping derived from the cluster analysis is based on the varying degree of influence of industrial discharges on the Alaro River sediment. The sediments collected (UI and U2) upstream are grouped together as Cluster 1, and sediment samples collected downstream are divided into two groups (Clusters 2 and 3). The reason for this separation is that locations D1, D2 and D3 which make up Cluster 2 contain significant input of Ni, Zn, Cr, Co, Cu, Cd and Pb from industrial discharges such that the sediment got enriched to high levels. Cluster 3 reflects relatively lower concentrations of the heavy metals than for Cluster 2.

The self-purification capacity of the Alaro River sediment is reflected with the decreasing trend of metal concentrations downstream. The distribution patterns observed for heavy metals in sediments of Alaro River were similar such that the concentrations of Ni, Zn, Cr, Co, Cu, Cd and Pb decreased downstream from the discharge point (Fig. 4). Regarding the reduction in metal concentrations in sediments as at the last sampling point, the concentrations decreased by 27.2% (Pb), 35.2% (Zn), 18.5% (Cr), 28.8% (Co), 15.2% (Cu), 11.8% (Cd) and 23.3% (Pb). Accumulation of heavy metals in sediments is usually a long-term pollution source. Toxic metals deposition on it can remain stored for many years unless remobilized by flooding and input of industrial discharges. Storage depends on the magnitude and frequency of the input (Zhao and Marriott 2013). The distribution pattern of toxic metals in sediments of Alaro River with distance downstream is similar to that of Severn River. For both rivers, the sand-sized particles are predominant and their association with heavy metals is such that remobilization of heavy metals can readily occur to possibly become secondary source of diffuse pollution. This possibility explains how heavy metals released into the Alaro River water system from the sediment particles by remobilization can be transported to pollute the adjoining Ona River. Dilution by the influx of upstream water flow is another possible mechanism by which concentrations of metals decrease downstream (Ipeaiyeda and Onianwa 2016).

Different studies have been published on data analysis using the least square model to explain the relation between heavy metal concentrations and distance of the river from the point of receiving polluted wastewater (Islam et al. 2015; Świetlik and Trojanowska 2016). Appropriate fitting of the experimental data using the regression model procedure carried out at 95% confidence limit produced a set of quadratic equations with R2 values ranging from 0.8810 to 0.9990 (Table 4).

Comparison of metal concentration in Alaro River sediment with other studies

The concentrations of metals in Alaro River sediment were lower than those found in sediments of Buriganga, Ganga and Korotoa Rivers. The only exception was that of copper whose concentration at downstream location (0.47 ± 0.03 mg/kg) was above the concentration range of copper (0.26–2.80 mg/kg) found in Korotoa River sediment. It seems the levels of heavy metals found in sediment of Alaro River would result in less adverse effect on the aquatic organisms compared to what the impact of the metals would be in the rivers of other countries. The Severn River was contaminated with Pb (33.2–291 mg/kg), Zn (108–232 mg/kg), Cu (14.4–24.5 mg/kg), Co (19.7–818 mg/kg) and Cd (1.6–2.8 mg/kg), resulting from the nonferrous metal process. In the sediment of the Severn River, sand-sized particles were predominant and their association with the heavy metals encouraged remobilization of metals in the river system. Sediments of Zhejiang coastal mud of China were enriched with potentially toxic metals (Cu, Pb, Zn, Cr and Cd) traceable to human activities. The concentrations of metals in this area as shown in Table 2 were more than the corresponding levels of metals in sediments of Alaro River which sourced from industrial discharges. Arising from industrialization, a large amount of wastewater containing heavy metals is discharged into the Red River in Vietnam. The discharge was such that the concentration of metals was higher in comparison to that of River Alaro sediment. The only exception was cobalt concentration (0.35 ± 0.27 mg/kg) which was lower than 0.47 ± 0.03 mg/kg obtained in this study (Table 2).

The distributions of heavy metals in sediment of the Pearl River in China (Zhen et al. 2016) were similar to the dispersion pattern of metals downstream observed in this study. The enrichment to toxic metals in these sediments was largely controlled by anthropogenic pollution.

Validation of analytical procedure

The standard reference material (SRM) which was analyzed along with the sediment samples for quality assurance purpose yielded satisfactory metal concentrations. The concentrations of Pb (40.0 ± 2.5 mg/kg), Cd (1.27 ± 0.30 mg/kg), Cu (32 ± 11 mg/kg), Co (17.5 ± 3.5 mg/kg), Cr (28.9 ± 5.1 mg/kg), Ni (23.5 ± 2.3 mg/kg), and Zn (202 ± 86 mg/kg) were not significantly different from the corresponding reference values of 39, 1.0, 38, 14, 34, 25 and 192, respectively, using student’s t-test at 95.0% confidence limit. The corresponding recovery values of replicate analysis of SRM were 103% (Pb), 127% (Cd), 84.0% (Cu), 125% (Co), 85.0% (Cr), 94.0% (Ni) and 105% (Zn).

Control of pollution sources

Sediments from the Alaro River are evidently burdened with toxic metals as manifested by a characteristic proportion of the heavy metals, EF and PLI. Disposal of inadequately treated effluents from the array of industries from Oluyole industrial estate can deplete dissolved oxygen and cause severe problems to aquatic life of the river. Hence, better control of industrial sources is needed to minimize or desist from discharging grossly contaminated wastewater into the river. In particular, heavy metals could be adequately removed by secondary effluent treatment process if all industries in the estate were to install efficient wastewater treatment plants (EWTP). Therefore, the local environmental protection agency should mandate and enforce all industries in the estate to comply with the installation of EWTP. This enforcement should subsequently be accompanied by proper monitoring of the industries.

In addition, the treated effluents could be channeled and employed by the government for irrigation by those farmers engaging in small-scale farming around the vacant plots of land in the estate. The treated effluent could be recycled to the water system used by the industries. Sludge produced as a product of inadequate treatment process in some industries around the estate is another major disposal problem that promotes the formation of contaminated sediment in the river. This sludge contains essential metals such as zinc which can enrich the plant if the sludge is spread out on the vacant land used for farming.

Conclusion

Investigation of heavy metals in downstream sediments of the Alaro River with respect to the upstream sediment revealed contamination with Ni, Zn, Cu, Co, Cr, Cd and Pb traceable to industrial discharges from Oluyole industrial area. The enrichment factors and pollution load corroborated the fact that the sediments contained heavy metal concentration above the background levels. The sediment was considered to be slightly toxic based on the toxicity estimation carried out. The study showed a decreasing trend of heavy metal contamination from the discharge point to the last downstream reach of the river. Regarding the marked increase in heavy metal released during industrial activities in areas such as Oluyole industrial estate that support the economic growth of the city, regular compliance monitoring of the river system and enforcement is required by the concerned board. This is because toxic metals are released during industrial activities. Therefore, water pollution control board of major cities worldwide should pay more attention to the risks associated with heavy metals in river system that plays an important role in social life of the people.

References

Ahmed MJK, Ahmaruzzaman M (2016) A review on potential usage of industrial waste materials for binding heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions. J Water Process Eng 10:39–47

Ali MM, Ali ML, Islam MS, Rahman MZ (2016) Preliminary assessment of heavy metals in water and sediment of Karnaphuli River, Bangladesh. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag 5:27–35

Banerjee S, Kumar A, Maiti SK, Chowdhury A (2016) Seasonal variation in heavy metal contaminations in water and sediments of Jamshedpur stretch of Subarnarekha river, India. Environ Earth Sci 75:1–12

Bian B, Zhou Y, Fang BB (2016) Distribution of heavy metals and benthic macroinvertebrates: impacts from typical inflow river sediments in the Taihu Basin, China. Ecol Ind 69:348–359

Burton GA Jr (2002) Sediment quality criteria in use around the world. Limnology 3:65–76

Chandran M, Mumtaz M, Thiruvalluvan M, Mangaleshwari R (2016) Heavy metals load and its impact on surface water quality of Vaigai river near Madurai city. World J Pharm Pharm Sci 5(5):1760–1770

du Plessis A (2017) Global water quality challenges, freshwater challenges of South Africa and its Upper Vaal River. Springer, Cham, pp 13–44

El Azhari A, Rhoujjati A, Hachimi MLE (2016) Assessment of heavy metals and arsenic contamination in the sediments of the Moulouya River and the Hassan II Dam downstream of the abandoned mine Zeïda (High Moulouya, Morocco). J Afr Earth Sc 119:279–288

Fernandes GW, Goulart FF, Ranieri BD, Coelho MS, Dales K, Boesche N, Bustamante M, Carvalho FA, Carvalho DC, Dirzo R (2016) Deep into the mud: ecological and socio-economic impacts of the dam breach in Mariana, Brazil. Nat Conserv 14:35–45

Garrido E, Camacho-Muñoz D, Martín J, Santos A, Santos JL, Aparicio I, Alonso E (2016) Monitoring of emerging pollutants in Guadiamar River basin (South of Spain): analytical method, spatial distribution and environmental risk assessment. Environ Sci Pollut Res 23:25127–25144

Hakanson L (1980) An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control. A sedimentological approach. Water Res 14:975–1001

Hakima Z, Mohamed M, Aziza M, Mehdi M, Bendahhou Z, Jean-Francois B (2017) Environmental and ecological risk of heavy metals in the marine sediment from Dakhla Bay, Morocco. Environ Sci Pollut Res 24(9):7970–7981

He W, Bai ZL, Liu WX, Kong XZ, Yang B, Yang C, Jørgensen SE, Xu FL (2016) Occurrence, spatial distribution, sources, and risks of polychlorinated biphenyls and heavy metals in surface sediments from a large eutrophic Chinese lake (Lake Chaohu). Environ Sci Pollut Res 23:10335–10348

Hurlimann H (1981) Office federal de la protection de l’environment 1971-1981: textes rediges a l’occasion de son dixieme anniversaire, Office federal de la protection de l’environment 1971-1981: textes rediges a l’occasion de son dixieme anniversaire

Ipeaiyeda AR, Onianwa PC (2011) Pollution effect of food and beverages effluents on the Alaro River in Ibadan City, Nigeria. Bull Chem Soc Ethiop 25(3):347–360

Ipeaiyeda AR, Onianwa PC (2016) Sediment quality assessment and dispersion pattern of toxic metals from brewery effluent discharged into the Olosun river, Nigeria. Environ Earth Sci 75:1–12

Islam MS, Ahmed MK, Raknuzzaman M, Habibullah-Al-Mamun M, Islam MK (2015) Heavy metal pollution in surface water and sediment: a preliminary assessment of an urban river in a developing country. Ecol Ind 48:282–291

Khatri N, Tyagi S, Rawtani D (2016) Assessment of drinking water quality and its health effects in rural areas of Harij Taluka, Patan district of Northern Gujarat. Environ Claims J 28:223–246

Knox AS, Paller MH, Milliken CE, Redder TM, Wolfe JR, Seaman J (2016) Environmental impact of ongoing sources of metal contamination on remediated sediments. Sci Total Environ 563:108–117

Li X, Wu Y, Zhang C, Liu Y, Zeng G, Tang X, Dai L, Lan S (2016) Immobilizing of heavy metals in sediments contaminated by nonferrous metals smelting plant sewage with sulfate reducing bacteria and micro zero valent iron. Chem Eng J 306:393–400

Long ER (2006) Calculation and uses of mean sediment quality guideline quotients: a critical review. Environ Sci Technol 40:1726–1736

Long ER, Morgan LG (1990) The potential for biological effects of sediments-sorbed contaminants tested in the National Status and Trends Program. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Silver Spring

Long ER, Macdonald DD, Smith SL, Calder FD (1995) Incidence of adverse biological effects within ranges of chemical concentrations in marine and estuarine sediments. Environ Manag 19:81–97

Loveland PJ, Whalley WR, Smith KA, Mullins CE (2000) Particle size analysis. In: Smith KA, Mullins CE (eds) Soil analysis–physical methods, pp 281–314

Nguyen TTH, Zhang W, Li Z, Li J, Ge C, Liu J, Bai X, Feng H, Yu L (2016) Assessment of heavy metal pollution in Red River surface sediments,Vietnam. Mar Pollut Bull 113:513–519

Nour ARA (1972) A statistical methodology for predicting the pollutants in a river. JAWRA J Am Water Resour Assoc 8:15–23

Pandey M, Tripathi S, Pandey AK, Tripathi B (2014) Risk assessment of metal species in sediments of the river Ganga. CATENA 122:140–149

Pansu M, Gautheyrou J (2007) Handbook of soil analysis: mineralogical, organic and inorganic methods. Springer Science & Business Media

Patra H, Adhikari SK, Kunar S (2016) Groundwater quality and contamination, groundwater prospecting and management. Springer, Singapore, pp 183–195

Peng X, Xiong S, Ou W, Wang Z, Tan J, Jin J, Tang C, Liu J, Fan Y (2017) Persistence, temporal and spatial profiles of ultraviolet absorbents and phenolic personal care products in riverine and estuarine sediment of the Pearl River catchment, China. J Hazard Mater 323:139–146

Persaud D, Jaagumagi R, Hayton A (1992) Guidelines for the protection and management of aquatic sediment quality in Ontario: Report. Water Resources Branch, Ontario Ministry of the Environment

Pourabadehei M, Mulligan CN (2016) Resuspension of sediment, a new approach for remediation of contaminated sediment. Environ Pollut 213:63–75

Rodríguez-Barranco M, Lacasaña M, Aguilar-Garduño C, Alguacil J, Gil F, González-Alzaga B, Rojas-García A (2013) Association of arsenic, cadmium and manganese exposure with neurodevelopment and behavioural disorders in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ 454:562–577

Salomons W, Förstner U (2012) Metals in the hydrocycle. Springer, Berlin

Shikazono N, Tatewaki K, Mohiuddin K, Nakano T, Zakir H (2012) Sources, spatial variation, and speciation of heavy metals in sediments of the Tamagawa River in Central Japan. Environ Geochem Health 34:13–26

Świetlik R, Trojanowska M (2016) Mobility of chromium and its chemical fractions in river sediment polluted by tannery effluents (Poland). Soil Sedim Contam Int J 25:266–278

Tamim U, Khan R, Jolly YN, Fatema K, Das S, Naher K, Islam MA, Islam SA, Hossain SM (2016) Elemental distribution of metals in urban river sediments near an industrial effluent source. Chemosphere 155:509–518

Tejeda-Benitez L, Flegal R, Odigie K, Olivero-Verbel J (2016) Pollution by metals and toxicity assessment using Caenorhabditis elegans in sediments from the Magdalena River, Colombia. Environ Pollut 212:238–250

Tomlinson D, Wilson J, Harris C, Jeffrey D (1980) Problems in the assessment of heavymetal levels in estuaries and the formation of a pollution index. Helgol Mar Res 33:566–575

Tripathee L, Kang S, Sharma CM, Rupakheti D, Paudyal R, Huang J, Sillanpää M (2016) Preliminary health risk assessment of potentially toxic metals in surface water of the Himalayan Rivers, Nepal. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 97:855–862

United State Environmental Protection (US EPA) (1999) National Recommended Water Quality Criteria–correction: EPA 822/Z-99-001

Venkatramanan S, Chung SY, Ramkumar T, Gnanachandrasamy G, Kim TH (2015) Evaluation of geochemical behavior and heavy metal distribution of sediments: the case study of the Tirumalairajan river estuary, southeast coast of India. Int J Sedim Res 30:28–38

Wang H, Sun L, Liu Z, Luo Q (2017) Spatial distribution and seasonal variations of heavy metal contamination in surface waters of Liaohe River, Northeast China. Chin Geogr Sci 27:52–62

Wu Q, Zhou H, Tam NF, Tian Y, Tan Y, Zhou S, Li Q, Chen Y, Leung JY (2016) Contamination, toxicity and speciation of heavy metals in an industrialized urban river: Implications for the dispersal of heavy metals. Mar Pollut Bull 104:153–161

Xu G, Liu J, Pei S, Hu G, Kong X (2016) Sources and geochemical background of potentially toxic metals in surface sediments from the Zhejiang coastal mud area of the East China Sea. J Geochem Explor 168:26–35

Ye F, Huang X, Zhang D, Tian L, Zeng Y (2012) Distribution of heavy metals in sediments of the Pearl River Estuary, Southern China: implications for sources and historical changes. J Environ Sci 24:579–588

Zhang C, Shan B, Tang W, Dong L, Zhang W, Pei Y (2017) Heavy metal concentrations and speciation in riverine sediments and the risks posed in three urban belts in the Haihe Basin. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 139:263–271

Zhao Y, Marriott SB (2013) Dispersion and remobilisation of heavy metals in the River Severn system, UK. Procedia Environ Sci 18:167–173

Zhen G, Li Y, Tong Y, Yang L, Zhu Y, Zhang W (2016) Temporal variation and regional transfer of heavy metals in the Pearl (Zhujiang) River, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 23:8410–8420

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ipeaiyeda, A.R., Onianwa, P.C. Monitoring and assessment of sediment contamination with toxic heavy metals: case study of industrial effluent dispersion in Alaro River, Nigeria. Appl Water Sci 8, 161 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-018-0815-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-018-0815-6