Abstract

Insulinoma is the commonest functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. The only curative treatment is surgical excision after preoperative localization. A retrospective analysis of nine patients (February 2017–June 2020), 2 males and 7 females, was done for clinical presentation, biochemistry, localization methods, intraoperative findings, postoperative outcome, histopathology reports, and follow-up. Techniques for localization of the tumor were pancreatic protocol triple-phase multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), Ga 68 DOTANOC PET-CT, and Ga 68 NOTA-exendin-4 PET-CT (GLP1R scan). The mean age was 38 (range 20–68) years and mean duration of symptoms 34 (range 8–120) months, and symptoms of Whipple’s triad were present in all cases after a supervised 72-h fast. MDCT localized tumor in 8/9 cases. EUS before MDCT in one patient had also localized tumors. Ga 68 DOTANOC PET-CT detected tumor in 2/4 patients. In one patient, MDCT or DOTANOC PET scan could not localize tumor; GLP1R scan localized tumor accurately. Two patients had associated MEN1 syndrome. All 9 patients underwent surgical resection (four open and five laparoscopic) of tumor-enucleation (3), distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy (3), and pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) (3). The last four procedures and all three enucleations were laparoscopic. Five patients developed postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF), only one grade B which required percutaneous drain placement. One patient, who had initial open enucleation, developed hypoglycemia after 48 h; PD was performed. All patients were cured and all, except one (who died of upper GI bleed), were alive and disease-free during a mean follow-up of 26 (range 2–41) months. Preoperative localization of insulinoma is important and decides the outcome of surgery in terms of cure. MDCT can localize tumors in most patients; the last resort for localization is the GLP1R scan. Laparoscopic procedures are equally effective compared to open surgery. Considering the benign nature of the disease, enucleation is the procedure of choice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Insulinomas are the most common cause of endogenous hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in adults [1]. Insulinoma is the most common functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (PNET), accounting for one-third to one-half of all PNETS and 1–2% of all pancreatic neoplasms [2,3,4,5]. Insulinomas are usually located in the pancreas, equally distributed in the head, body, and tail, extra-pancreatic extremely rare (< 2%), mostly located in the duodenal wall [6]. Surgical removal is the treatment of choice but accurate localization of the tumor is the key to successful surgical management. Insulinoma can be sporadic or part of multiple endocrine neoplasia1 (MEN1) syndrome. Eighty percent of sporadic insulinomas are small and intrapancreatic, thus making preoperative localization unsuccessful in 10–25% of cases [1]. There are very few reports of insulinoma from India [7,8,9,10].

In this study, we present a single-center experience with insulinoma and highlight the importance of accurate preoperative localization for successful surgical management.

Patients and Methods

Between February 2017 and June 2020, nine patients with a final diagnosis of insulinoma were identified at a tertiary care center in west India. The medical records of these patients were reviewed for demographic data, clinical presentation, biochemistry, localization methods, intraoperative findings, postoperative outcome, histopathology reports, and follow-up.

Biochemical diagnostic criteria used for the diagnosis of insulinoma were plasma concentration of glucose < 55 mg/dl, insulin level of at least 3.0 µIU/ml, and C-peptide level of at least 0.6 ng/ml [11]. A 72-h fasting test was done on all patients. All the cases were screened for MEN syndrome after confirming the diagnosis of insulinoma.

Techniques for localization of the tumor were pancreatic protocol triple-phase multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), Ga 68 DOTANOC PET-CT, and Ga 68 NOTA-exendin-4 PET-CT (GLP1R scan).

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is defined as per the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) [12].

All statistical analyses were done using the computer program Microsoft Excel 2019.

Results (Table 1)

Clinical Profile

A total of 9 patients, 2 males and 7 females, with a mean age of 38 (range 20–68) years were diagnosed with an insulinoma. All the patients presented with typical features of Whipple’s triad, i.e., symptoms of hypoglycemia, low blood glucose levels, and relief of symptoms after glucose administration; the mean duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 34 (range 8–120) months. Two patients had insulinoma associated with MEN 1 syndrome.

Biochemical Analysis

All patients had typical neuroglycopenic symptoms with hypoglycemia. All patients underwent a supervised 72-h fast test; mean plasma concentration of glucose was 41 (range 30–54) mg/dl, insulin 8.3 (range 3.1–16) µIU/ml, and C-peptide 1.9 (range 0.9–4.3) ng/ml.

Preoperative Localization

Once hypoglycemia was documented, preoperative localization procedures were done. All patients underwent pancreatic protocol triple-phase multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) which was able to locate the tumor in 8/9 cases. One patient had undergone EUS before coming to our center which had also localized the tumor. Due to financial constraints, we were able to get Ga 68 DOTANOC PET-CT done in 4 patients only and it detected the tumor in only 2/4 patients. In one patient, we were not able to localize the tumor with either MDCT or DOTANOC PET scan; this patient underwent GLP1R scan which localized the site of the tumor accurately.

Operative Procedure

After preoperative localization, all nine patients underwent surgical resection of the tumor—this included enucleation in three, distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy in three, and pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) in three patients. Four patients had open and five underwent laparoscopic procedures. The last four procedures and all three enucleations were done laparoscopically; no blind surgery in the form of distal pancreatectomy had to be performed, because of accurate preoperative localization of the tumor in all cases. The mean postoperative hospital stay was 8 (range 3–14) days.

Syndromic Insulinoma

On hormonal work-up, two patients were found to have associated MEN1 syndrome. The first patient was a 45-year-old female with typical clinical diagnostic features of primary hyperparathyroidism, insulinoma, and multiple collagenoma but genetic work-up could not be done because of financial constraints. The second patient was a 20-year-old female with parathyroid adenoma with microprolactinoma diagnosed to have menin gene on genetic work-up.

Perioperative Blood Sugar Management

Patients were started on intravenous dextrose and intermittent D25 infusions with hourly blood sugar monitoring. In the operation theater, dextrose drip was stopped just after the removal of the tumor and normal saline with insulin infusion was started, if required, to maintain the blood sugar around 200 mg/dl. One patient required insulin even after discharge but it was stopped after 1 month on follow-up.

Histopathology

Mean tumor size was 2.6 (range 1.5–5.5) cm. The tumor was located in the pancreatic head (2), uncinate process (1), body (4), and tail (2) of the pancreas. All tumors were benign, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor grade I. Immunohistochemical marker study was also suggestive of insulinoma in all patients.

Postoperative Complications

Only two out of the nine patients had major (Clavien-Dindo grade IIIa and IIIb) complications. One of these two patients with grade B POPF required percutaneous drain placement. The other patient initially underwent open enucleation of the tumor; histology revealed insulinoma. But the patient developed an episode of hypoglycemia after 48 h and a repeat MDCT revealed a remaining tumor, so PD was performed; histology was residual insulinoma. Four patients had grade BL (biochemical leak) POPF which settled on its own. Three patients did not have any complications.

Follow-up

The mean follow-up period was 26 (range 2–41) months and none of the patients was lost to follow-up. All patients were cured of the disease and, except one, all were alive and disease-free during the follow-up. One patient developed an upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleed after pancreatic stent removal on follow-up; the bleed initially stopped with conservative treatment but he again had another episode of UGI bleed and died 2 months after surgery. None of the patients developed recurrence.

Discussion

Very few reports of insulinoma have been published in India. Paul et al. [7] published their experience with 18 patients managed at the Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore, over 10 years (1995–2005) [7]; Gopal et al. [8] published their experience with 26 patients managed at the King Edward Memorial (KEM) Hospital, Mumbai, over 16 years (1993–2009) [8]; and Jyotsna et al. (2006) published their experience of 31 patients at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, over 13 years (1992–2005) [9] and later in 2016 of 35 patients over 8 years (2006–2013). We report our experience with 9 patients managed over 3 years (2017–2020) [10].

Two males and seven females in our study suggest female preponderance which is similar to other studies [13]. The mean age of presentation was in the fourth decade and the mean duration of symptoms before diagnosis was long, i.e., 34 (range 8–120) months, because symptoms of hypoglycemia are vague and non-specific [6]. Clinically, these patients have varied neurological symptoms ranging from simple confusion and neurocognitive deficits to frank seizures and even coma [14, 15]. Typical manifestations of insulinoma are the symptoms of hypoglycemia usually provoked by fasting or exercise [16]. A wide spectrum of clinical manifestations in patients with insulinoma is the reason for the difficult recognition of the disease with a long time interval between the onset of the symptoms and the diagnosis. Insulinoma is confirmed by the presence of endogenous hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. The diagnostic “gold standard” for insulinoma is the 72-h fast test [17]. One-third of patients develop corresponding symptoms within 12 h, 80% within 24 h, 90% within 48 h, and almost 100% of patients within 72 h after the test initiation [6]. The 72-h fast test was done in all our patients and the results were positive as per the standard guidelines. Diagnosis of endogenous hyperinsulinism can be made by the presence of blood glucose level < 55 mg/dl (3.0 mmol/l); concomitant insulin level ≥ 3 µIU/ml (≥ 18 pmol/L); C-peptide level ≥ 0.6 ng/ml (0.2 nmol/L); and proinsulin level 5.0 pmol/L [18]. The mean insulin and C-peptide levels in our study were similar to the NIH data [19].

Medical therapy can control hypoglycemic symptoms in approximately 50–60% of patients with insulinoma but surgery remains the only curative treatment [20]. Surgical excision is the definitive treatment and the majority of the patients become symptom-free after surgical removal of the tumor [16]. The most important factor in the successful surgical management of insulinoma is the preoperative localization of the tumor in the pancreas [21]. The recurrence rate is about 7% in insulinomas without MEN 1 but increases to 21% in those with MEN 1 [22]. Preoperative localization facilitates pancreas-preserving surgery such as enucleation or limited segmental resection [23], decreases the operating time, increases the chances of surgical cure, and prevents the need for repeat surgeries [19, 24, 25].

A basket of preoperative localization modalities is currently available and these range from non-invasive imaging such as abdominal ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to invasive modalities such as arteriography, transhepatic portal venous sampling (THPVS), intraarterial calcium stimulation with hepatic venous sampling (ASVS), endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), and intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS). Recently, newer modalities for localization, e.g., Ga 68 DOTANOC PET-CT, Ga 68 DOTATATE PET-CT, and Ga 68 NOTA-exendin-4 PET-CT (GLP1R scan), have been described which have sensitivities up to 98% [26].

Though US is a widely available, non-invasive, low-cost test, it was not done in our study for localization as it is highly operator-dependent and 9–66% can only be localized [27, 28]. Contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) using microbubbles is more accurate with a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 87%, because of the strong vascularity of the insulinomas [29, 30].

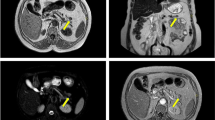

In our study, we performed MDCT in all patients with a sensitivity of 89%, similar to other studies. CT is a simple and safe procedure to perform that is operator-independent. CECT of the abdomen is one of the most commonly used diagnostic procedure with a sensitivity of 35–82% [31, 32]. The thin-section MDCT is more accurate, reaching a sensitivity of 83–94% [33, 34]. CT visualizes the exact location of an insulinoma, its relationship to vital structures, and the presence of metastases [35]. Multi-phase CECT is currently accepted as the first-line investigation for the visualization of insulinoma. Typically, insulinomas are hypervascular and, as a result, demonstrate a greater degree of enhancement than the normal pancreatic parenchyma during the arterial and capillary phases of contrast bolus (Fig. 1) [36]. Atypical CT appearances of insulinoma are occasionally encountered and can include hyperdense lesions precontrast, hypovascular and hypodense lesions post-contrast, cystic masses, and calcified masses [36]. Calcification, when it occurs, tends to be discrete and nodular, and is more common in malignant than in benign tumors [37, 38]. Technical advances have improved the quality of CT, with a recent study reporting that an MDCT enabled visualization of as many as 94% of insulinomas [34].

We did not perform MRI in our cases but, currently, strong evidence is emerging for the use of MRI in the imaging of insulinomas and investigators have shown high sensitivity for MRI in the detection of insulinomas [35]. The sensitivity of MRI for the localization of an insulinoma is 35–63% and can detect smaller lesions than CT scans [27, 39]. Like CT, MRI is safe, non-invasive, and rapid, and facilitates the detection of metastases. Insulinomas generally demonstrate low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images [37]. In current practice, MRI is a second-line (after CT) investigation for the localization of insulinomas, but it could potentially take over from CT in the future as it becomes more widely available and expertise improves.

The most accurate diagnostic tool for insulinomas is EUS with a sensitivity of 94% alone or up to 100% when combined with CT [27, 31]. EUS gives information on the adjacent lymph nodes also [27, 40, 41] and its power of detection is maximum for lesions in the head and the body of the pancreas with a sensitivity of 95% and 98%, respectively [31]. It allows to perform biopsy or cytology with fine-needle aspiration [42] and mark the lesion with a tattooing agent [43]. EUS also helps to know whether tumor enucleation is possible as it can estimate the distance between the tumor and the main pancreatic duct [44]. The limitations are that it is invasive, operator-dependent, and frequently incapable of detecting tumors of the pancreatic tail [31, 45]. In our study, EUS was done in only one patient before the patient was referred to our center and it detected the tumor accurately.

Despite this wide array of localization modalities available, some investigators still prefer to minimize the number of preoperative investigations, as surgical exploration with palpation and intraoperative ultrasonography (IOUS) by experienced surgeons has consistently been shown to have an impressive overall sensitivity of 95 to 100% [46, 47]. At our center, we did not have to perform IOUS in any case because we were able to localize the tumor preoperatively in all patients.

18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET is not useful for the diagnosis of insulinoma because of its low proliferation rate [27]. Different somatostatin receptors (SSTR) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptors are expressed by benign and malignant neoplasms [26, 48, 49]. In our study, Ga 68 DOTANOC PET-CT accurately localized the tumor in only 2 out of 4 patients because benign insulinomas show a low expression of SSTR subtype 2, with a sensitivity of 25–31% [50,51,52]. Prasad et al. found that SSTR2 expression in insulinomas is present in up to 80% of cases [53] and, in a recent study, 68 Ga-DOTATATE scans localized the tumor in 9 out of 10 cases (sensitivity of 90%) [54]. Benign insulinomas express GLP-1R on the cell surface with high (> 90%) incidence and high density [48], which makes them highly detectable with GLP-1R scan, a technique that uses an agonist of GLP-1R, even though it is not widely available. In the prospective study conducted in 2016 by Luo Y et al., GLP-1R showed a sensitivity of 98% [26, 55, 56]. In our study, in one patient in whom other investigations failed, GLP-1R scan accurately localized the tumor (Fig. 2).

Invasive localization studies such as arteriography and selective arterial calcium stimulation test (SACST) have the sensitivity of 70–100%, but in clinical practice are not used now because of their invasiveness [57].

With the use of accurate preoperative localization, the Mayo Clinic reported the reduction of blind explorations from 26 to 0% over the last 20 years [58].

After the localization of the tumor, surgery is the only curative treatment. In our study, no blind distal pancreatectomy was performed as it used to be done in past in the management of patients with occult insulinoma [7, 8]. The exact surgical procedure for insulinoma remains a matter of debate, although most investigators would advocate a pancreas-sparing approach [7, 47]. One of the studies found enucleation to be associated with a higher risk of microscopic positive margins compared with a formal resection (38% vs 0%, p = 0.043) but R1 resection was not associated with an increase in recurrence or reduced survival [59, 60]. Our patients’ surgery was done by both open and laparoscopic techniques and included resection and/or enucleation. Laparoscopically, total of five procedures were done including enucleation in three and distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy in two. This was possible because of preoperative localization. The success rate of laparoscopic resection is 70–100% with minimal mortality and equivalent safety and efficacy rates as open resection [28]. To achieve better accuracy in localization, one can use the laparoscopic US. Laparoscopic surgery, including enucleation, is being increasingly used to treat insulinomas and may become the surgical approach of choice in the future [7, 61].

The cure rate of surgery is 77–100% [49] and overall survival after resection is 97% at 5 years and 88% at 10 years [20]. In our study, we were able to get a 100% cure because of accurate preoperative localization of the tumor in all cases. All (except one, who died) of our patients are symptom-free on follow-up and without any recurrence of the disease.

None of our patients was found to have nesidioblastosis which is an abnormal proliferation of β cells throughout the entire pancreas [62]. It is a rare cause of adult hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia seen in only 0.5 to 5% of cases [63]. It is difficult clinically and biochemically to distinguish between diffuse nesidioblastosis and insulinoma [64]. The treatment of adult nesidioblastosis is surgical resection of the pancreas in the form of subtotal pancreatectomy leaving a rim of pancreatic tissue attached to the second part of the duodenum [65].

Insulinomas can be sporadic or a part of MEN 1 syndrome. Ninety percent of insulinomas measure < 2 cm and 30% are < 1 cm in diameter. Ten percent are multiple, 10% are malignant [66], and 10% are associated with MEN 1 [67]. The average age of occurrence is 45 years for sporadic cases and 25 years for MEN 1 [1, 4, 68]. Sporadic insulinomas are usually solitary, benign, and encapsulated small lesions. MEN1 patients may present with multiple tumors in 80% of cases so the surgical approach should be more aggressive and radical [69]. In our study, two patients had associated MEN 1; both underwent distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy (no other tumor was present in the pancreas during surgery) and in one parathyroidectomy was also required.

Limitations of our study are its retrospective nature and the small number of patients but we were able to achieve 100% preoperative localization of the tumor, using mainly MDCT and supportive imaging modalities 68 Ga DOTANOC PET-CT and GLP1R scan. This ensured complete excision of the tumor and symptom-free survival during a follow-up of more than 24 months.

Conclusion

After clinical suspicion and biochemical diagnosis, preoperative localization of insulinoma is very important and will decide the outcome of surgery in the form of a cure. MDCT can localize the tumor in most patients. The last resort for localization is the GLP1R scan which can detect insulinoma with 100% sensitivity. Laparoscopic procedures are equally effective compared to open surgery. Considering the benign nature of the disease, enucleation is the procedure of choice.

References

Grant CS (2005) Insulinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 19(5):783–798

Halfdanarson TR, Rubin J, Farnell MB, Grant CS, Petersen GM (2008) Pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: epidemiology and prognosis of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer 15(2):409

Ito T, Igarashi H, Jensen RT (2012) Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: clinical features, diagnosis and medical treatment: advances. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 26(6):737–753

Öberg K, Eriksson B (2005) Endocrine tumours of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 19(5):753–781

Sotoudehmanesh R, Hedayat A, Shirazian N, Shahraeeni S, Ainechi S, Zeinali F, Kolahdoozan S (2007) Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) in the localization of insulinoma. Endocrine 31(3):238–241

Okabayashi T, Shima Y, Sumiyoshi T, Kozuki A, Ito S, Ogawa Y, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K (2013) Diagnosis and management of insulinoma. World J Gastroenterol: WJG 19(6):829–837

Paul TV, Jacob JJ, Vasan SK, Thomas N, Rajarathnam S, Selvan B, Paul MJ, Abraham D, Nair A, Seshadri MS (2008) Management of insulinomas: analysis from a tertiary care referral center in India. World J Surg 32(4):576–582

Gopal RA, Acharya SV, Menon SK, Bandgar TR, Menon PS, Shah NS (2010) Clinical profile of insulinoma: analysis from a tertiary care referral center in India. Indian J Gastroenterol 29(5):205–208

Jyotsna VP, Rangel N, Pal S, Seith A, Sahni P, Ammini AC (2006) Insulinoma: diagnosis and surgical treatment Retrospective analysis of 31 cases. Indian J Gastroenterol. 25(5):244

Jyotsna VP, Pal S, Kandasamy D, Gamanagatti S, Garg PK, Raizada N, Sahni P, Bal CS, Tandon N, Ammini AC (2016) Evolving management of insulinoma: experience at a tertiary care centre. Indian J Med Res 144(5):771

Hsien-chiu T, Chong-zheng Y, Shou-xian Z, Jian-xi Z, Yu Z (1984) Percutaneous transhepatic portal vein catheterization for localization of insulinoma. World J Surg 8(4):575–581

Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, Allen P, Andersson R, Asbun HJ, Besselink MG, Conlon K, International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) (2017) The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surgery. 161(3):584–91

Iglesias P, Díez JJ (2014) Management of endocrine disease: a clinical update on tumor-induced hypoglycemia. Eur J Endocrinol 170(4):R147–R157

Valente LG, Antwi K, Nicolas GP, Wild D, Christ E (2018) Clinical presentation of 54 patients with endogenous hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycemia: a neurological chameleon (observational study). Swiss Med Wkly 148:w14682. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2018.14682

Jagadheesan V, Suresh SS (2008) Episodic confusional state: due to insulinoma. Indian J Psychiatry 50(3):197

Boukhman MP, Karam JH, Shaver J, Siperstein AE, Duh QY, Clark OH (1998) Insulinoma–experience from 1950 to 1995. West J Med 169(2):98

Service FJ (1995) Hypoglycemic disorders. N Engl J Med 332(17):1144–1152

Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, Heller SR, Montori VM, Seaquist ER, Service FJ (2009) Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94(3):709–28

Guettier JM, Kam A, Chang R, Skarulis MC, Cochran C, Alexander HR, Libutti SK, Pingpank JF, Gorden P (2009) Localization of insulinomas to regions of the pancreas by intraarterial calcium stimulation: the NIH experience. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94(4):1074–1080

Abboud B, Boujaoude J (2008) Occult sporadic insulinoma: localization and surgical strategy. World J Gastroenterol: WJG 14(5):657

Van Nieuwenhove Y, Vandaele S, de Beeck BO, Delvaux G (2003) Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas. Surgical Endoscopy And Other Interventional Techniques 17(10):1658–1662

Service FJ, McMahon MM, O’Brien PC, Ballard DJ (1991) Functioning insulinoma—incidence, recurrence, and long-term survival of patients: a 60-year study. Mayo Clin Proc 66(7):711–719

Falconi M, Mantovani W, Crippa S, Mascetta G, Salvia R, Pederzoli P (2008) Pancreatic insufficiency after different resections for benign tumours. J Br Surg 95(1):85–91

Gupta RA, Patel RP, Nagral S (2013) Adult onset nesidioblastosis treated by subtotal pancreatectomy. JOP 14(3):286–288

Doppman JL, Chang R, Fraker DL, Norton JA, Alexander HR, Miller DL, Collier E, Skarulis MC, Gorden P (1995) Localization of insulinomas to regions of the pancreas by intra-arterial stimulation with calcium. Ann Intern Med 123(4):269–273

Luo Y, Pan Q, Yao S, Yu M, Wu W, Xue H, Kiesewetter DO, Zhu Z, Li F, Zhao Y, Chen X (2016) Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor PET/CT with 68Ga-NOTA-exendin-4 for detecting localized insulinoma: a prospective cohort study. J Nucl Med 57(5):715–720

De Herder WW, Niederle B, Scoazec JY, Pauwels S, Klöppel G, Falconi M, Kwekkeboom DJ, Öberg K, Eriksson B, Wiedenmann B, Rindi G (2006) Well-differentiated pancreatic tumor/carcinoma: insulinoma. Neuroendocrinology 84(3):183–188

Mathur A, Gorden P, Libutti SK (2009) Insulinoma. Surg Clin 89(5):1105–1121

An L, Li W, Yao KC, Liu R, Lv F, Tang J, Zhang S (2011) Assessment of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in diagnosis and preoperative localization of insulinoma. Eur J Radiol 80(3):675–680

Wang H, Ba Y, Xing Q, Du JL (2018) Diagnostic value of endoscopic ultrasound for insulinoma localization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 13(10):e0206099

McLean A (2004) Endoscopic ultrasound in the detection of pancreatic islet cell tumours. Cancer Imaging 4(2):84

Burghardt L, Meier JJ, Uhl W, Kahle-Stefan M, Schmidt WE, Nauck MA (2019) Importance of localization of insulinomas: a systematic analysis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 26(9):383–392

Fidler JL, Fletcher JG, Reading CC, Andrews JC, Thompson GB, Grant CS, Service FJ (2003) Preoperative detection of pancreatic insulinomas on multiphasic helical CT. Am J Roentgenol. 181(3):775–80

Gouya H, Vignaux O, Augui J, Dousset B, Palazzo L, Louvel A, Chaussade S, Legmann P (2003) CT, endoscopic sonography, and a combined protocol for preoperative evaluation of pancreatic insulinomas. Am J Roentgenol 181(4):987–992

McAuley G, Delaney H, Colville J, Lyburn I, Worsley D, Govender P, Torreggiani WC (2005) Multimodality preoperative imaging of pancreatic insulinomas. Clin Radiol 60(10):1039–1050

Noone TC, Hosey J, Firat Z, Semelka RC (2005) Imaging and localization of islet-cell tumours of the pancreas on CT and MRI. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 19(2):195–211

Balci NC, Semelka RC (2001) Radiologic diagnosis and staging of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Radiol 38(2):105–112

Kurosaki Y, Kuramoto K, Itai Y (1996) Hyperattenuating insulinoma at unenhanced CT. Abdom Imaging 21(4):334–336

Antwi K, Fani M, Heye T, Nicolas G, Rottenburger C, Kaul F, Merkle E, Zech CJ, Boll D, Vogt DR, Gloor B (2018) Comparison of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) PET/CT, SPECT/CT and 3T MRI for the localisation of occult insulinomas: evaluation of diagnostic accuracy in a prospective crossover imaging study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 45(13):2318–2327

Öberg K (2010) Pancreatic endocrine tumors. In Seminars in oncology. 37(6):594–618). WB Saunders

Tsang YP, Lang BH, Shek TW (2016) Assessing the short-and long-term outcomes after resection of benign insulinoma. ANZ J Surg 86(9):706–710

Kann P, Moll R, Bartsch D, Pfützner A, Forst T, Tamagno G, Goebel J, Fourkiotis V, Bergmann S, Collienne M (2017) Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNA) in insulinomas: indications and clinical relevance in a single investigator cohort of 47 patients. Endocrine (1355008X) 56(1)

Luigiano C, Ferrara F, Morace C, Mangiavillano B, Fabbri C, Cennamo V, Bassi M, Virgilio C, Consolo P (2012) Endoscopic tattooing of gastrointestinal and pancreatic lesions. Adv Ther 29(10):864–873

Joseph AJ, Kapoor N, Simon EG, Chacko A, Thomas EM, Eapen A, Abraham TD, Jacob PM, Paul T, Rajaratnam S, Thomas N (2013) Endoscopic ultrasonography-a sensitive tool in the preoperative localization of insulinoma. Endocr Pract 19(4):602–608

Challis BG, Powlson AS, Casey RT, Pearson C, Lam BY, Ma M, Pitfield D, Yeo GS, Godfrey E, Cheow HK, Chatterjee VK (2017) Adult-onset hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia in clinical practice: diagnosis, aetiology and management. Endocr Connect 6(7):540–548

Lo CY, Lam KY, Kung AW, Lam KS, Tung PH, Fan ST (1997) Pancreatic insulinomas: a 15-year experience. Arch Surg 132(8):926–930

Rothmund M, Angelini L, Brunt LM, Farndon JR, Geelhoed G, Grama D, Herfarth C, Kaplan EL, Largiader F, Morino F, Peiper HJ (1990) Surgery for benign insulinoma: an international review. World J Surg 14(3):393–398

Korner M, Christ E, Wild D, Reubi JC (2012) Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor overexpression in cancer and its impact on clinical applications. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 3:158

Portela-Gomes GM, Stridsberg M, Grimelius L, Rorstad O, Janson ET (2007) Differential expression of the five somatostatin receptor subtypes in human benign and malignant insulinomas–predominance of receptor subtype 4. Endocr Pathol 18(2):79–85

Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, Bartsch DK, Capdevila J, Caplin M, Kos-Kudla B, Kwekkeboom D, Rindi G, Klöppel G, Reed N (2016) ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of patients with functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology 103(2):153–171

Luo Y, Yu M, Pan Q, Wu W, Zhang T, Kiesewetter DO, Zhu Z, Li F, Chen X, Zhao Y (2015) ^ sup 68^ Ga-NOTA-exendin-4 PET/CT in detection of occult insulinoma and evaluation of physiological uptake. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 42(3):531

Sharma P, Arora S, Dhull VS, Naswa N, Kumar R, Ammini AC, Bal C (2015) Evaluation of 68 Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT imaging in a large exclusive population of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Abdom Imaging 40(2):299–309

Prasad V, Sainz-Esteban A, Arsenic R, Plöckinger U, Denecke T, Pape UF, Pascher A, Kühnen P, Pavel M, Blankenstein O (2016) Role of 68 Ga somatostatin receptor PET/CT in the detection of endogenous hyperinsulinaemic focus: an explorative study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 43(9):1593–1600

Nockel P, Babic B, Millo C, Herscovitch P, Patel D, Nilubol N, Sadowski SM, Cochran C, Gorden P, Kebebew E (2017) Localization of insulinoma using 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT scan. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102(1):195–199

Sharma P, Arora S, Karunanithi S, Khadgawat R, Durgapal P, Sharma R, Kandasamy D, Bal C, Kumar R (2014) Somatostatin receptor based PET/CT imaging with 68Ga-DOTA-Nal3-octreotide for localization of clinically and biochemically suspected insulinoma. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 60(1):69–76

Brown E, Watkin D, Evans J, Yip V, Cuthbertson DJ (2018) Multidisciplinary management of refrsactory insulinomas. Clin Endocrinol 88(5):615–624

Shin JJ, Gorden P, Libutti SK (2010) Insulinoma: pathophysiology, localization and management. Future Oncol 6(2):229–237

Placzkowski KA, Vella A, Thompson GB, Grant CS, Reading CC, Charboneau JW, Andrews JC, Lloyd RV, Service FJ (2009) Secular trends in the presentation and management of functioning insulinoma at the Mayo Clinic, 1987–2007. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94(4):1069–73

Nikfarjam M, Warshaw AL, Axelrod L, Deshpande V, Thayer SP, Ferrone CR, Fernández-del CC (2008) Improved contemporary surgical management of insulinomas: a 25-year experience at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Ann Surg 247(1):165

Goh BK, Ooi LL, Cheow PC, Tan YM, Ong HS, Chung YF, Chow PK, Wong WK, Soo KC (2009) Accurate preoperative localization of insulinomas avoids the need for blind resection and reoperation: analysis of a single institution experience with 17 surgically treated tumors over 19 years. J Gastrointest Surg 13(6):1071–1077

Fernández-Cruz L, Cesar-Borges G (2006) Laparoscopic strategies for resection of insulinomas. J Gastrointest Surg 10(5):752–760

Witteles RM, Straus FH II, Sugg SL, Koka MR, Costa EA, Kaplan EL (2001) Adult-onset nesidioblastosis causing hypoglycemia: an important clinical entity and continuing treatment dilemma. Arch Surg 136(6):656–663

Anlauf M, Wieben D, Perren A, Sipos B, Komminoth P, Raffel A, Kruse ML, Fottner C, Knoefel WT, Mönig H, Heitz PU (2005) Persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in 15 adults with diffuse nesidioblastosis: diagnostic criteria, incidence, and characterization of β-cell changes. Am J Surg Pathol 29(4):524–533

Toyomasu Y, Fukuchi M, Yoshida T, Tajima K, Osawa H, Motegi M, Iijima T, Nagashima K, Ishizaki M, Mochiki E, Kuwano H (2009) Treatment of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia due to diffuse nesidioblastosis in adults: a case report. Am Surg 75(4):331–334

Klöppel G, Anlauf M, Raffel A, Perren A, Knoefel WT (2008) Adult diffuse nesidioblastosis: genetically or environmentally induced? Hum Pathol 39(1):3–8

Klöppel G, Anlauf M (2006) Pancreatic endocrine tumors. AJSP: Rev Rep 11(6):256–67

Callender GG, Rich TA, Perrier ND (2008) Multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Surg Clin North Am 88(4):863–895

Jani N, Moser AJ, Khalid A (2007) Pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 36(2):431–439

Antonakis PT, Ashrafian H, Martinez-Isla A (2015) Pancreatic insulinomas: laparoscopic management. World J Gastrointest Endosc 7(16):1197

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, A., Varshney, P., Kasliwal, R. et al. Insulinoma—Accurate Preoperative Localization Is the Key to Management: An Initial Experience. Indian J Surg Oncol 13, 403–411 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-022-01534-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-022-01534-6