Abstract

Objectives

In order to provide a broad overview of the body of peer-reviewed literature on self-compassion and close relationships, this scoping review describes how self-compassion relates to thoughts, feelings, and behaviors within the context of current personal relationships between family members, romantic partners, friends, or others referred to as “close.”

Methods

Two reviewers independently screened peer-reviewed articles retrieved based on a defined search strategy within three online databases, extracted data from 72 articles that met inclusion criteria by consensus, and summarized findings thematically.

Results

With few exceptions, self-compassion is positively associated with secure attachment, adaptive parenting behaviors, healthy family, romantic and friendship functioning, and constructive conflict and transgression repair behavior. In families, evidence suggests that parent self-compassion is linked to supportive parenting behavior, which is in turn linked to higher levels of child self-compassion.

Conclusions

Self-compassion is associated with a wide variety of close interpersonal relationship benefits. These associations may be complex and bidirectional, such that positive social relationships promote self-compassion, while self-compassion promotes relational and emotional well-being. For a deeper understanding of these nuances and to establish causality, future research should include heterogeneous samples, longitudinal designs, and observational and multi-informant methodologies, and consider attachment style and personality trait covariates. The potential implications for interventional research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Compassion has been described as an affective state where one is attentive to and emotionally affected by another’s suffering, with subsequent motivation to help the person in distress (Goetz et al. 2010). Similarly, rooted in Buddhist tradition, self-compassion is described as treating oneself with care and support during times of difficulty. Neff (2003a) conceptualized self-compassion as a dynamic construct that entails three inter-related aspects. First, self-compassion involves self-kindness, which refers to warm, self-soothing responses to distress, as opposed to self-criticism. A second element is common humanity, which is described as the recognition that all people encounter hardships and emotional distress at one time or another. This attitude promotes a sense of connection rather than isolation or self-pity amidst difficulty. Finally, self-compassion includes mindfulness, which refers to a balanced and non-judgmental response to negative emotions, as opposed to avoiding or becoming overwhelmed by them. Evidence suggests that self-compassion is both an adaptive emotion regulation strategy and resilience factor (Finlay-Jones 2017; Trompetter et al. 2017), with meta-analyses demonstrating strong positive associations with well-being in adults (Zessin et al. 2015) and inverse associations with anxiety, depression, and stress in adult and adolescent samples (MacBeth and Gumley 2012; Marsh et al. 2018).

In addition to links to individual well-being, growing evidence suggests that self-compassion is linked to various aspects of interpersonal well-being. For example, self-compassion is linked to altruism, empathy, perspective taking, willingness to forgive and apologize, and social connectedness (Fuochi et al. 2018; Howell et al. 2011; Neff and Pommier 2013). Self-compassion is linked to lower levels of personal distress in response to another’s difficulty, which may explain increased willingness to help others (Welp and Brown 2014). Individuals high in self-compassion also report less over-dependency on others (Denckla et al. 2017) and appear less negatively impacted when receiving critical feedback from others (Leary et al. 2007). Thus, it is plausible that by tending to one’s own emotional needs compassionately and from a “shared humanity” perspective, one is better equipped to recognize and respond skillfully to the needs of others.

Moreover, the link between self-compassion and interpersonal well-being may be bidirectional, such that those who have experienced caring, supportive relationships develop greater capacity to be self-compassionate. For example, adolescents and adults who recall warm and supportive childhood experiences report higher levels of self-compassion (Kelly and Dupasquier 2016; Marta-Simões et al. 2016; Temel and Atalay 2018). Alternatively, those who recall their childhood caregivers showing low warmth, rejection, or indifference, or those who experienced abuse, report lower self-compassion levels (Pepping et al. 2015; Potter et al. 2014; Tanaka et al. 2011; Westphal et al. 2016). These findings suggest that self-compassion may co-develop with secure attachment, or the enduring emotional bond that a child has with a caregiver who is responsive to his or her needs (Cassidy 2018). Evidence consistently shows that secure attachment provides a basis for healthy self-relating and the capacity for intimate relationships throughout the lifespan (Shaver et al. 2016). Likewise, it is posited that experiencing support from early caregivers provides the foundation for supportive and self-compassionate inner dialogs in adulthood (Neff and McGehee 2010).

Despite evidence suggesting that self-compassion and interpersonal well-being may influence one another and may be rooted in one’s early caregiving experiences, less is known about the role of self-compassion in specific current close relationship contexts. There are also mixed findings regarding self-compassion and interpersonal factors. For example, a longitudinal study of adolescents across 9th to 12th grades found that self-compassion did not contribute to general prosocial behavior development (i.e., willingness to help others in need) over time (Marshall et al. 2020). Similarly, several studies have found no relationship between self-compassion and general concern or compassion for others (Gerber et al. 2015; López et al. 2018).

Given this background, the purpose of this study is to broadly explore the evidence regarding the role of self-compassion in the context of current close relationships including family members, romantic partners, and friends. We explore close relationships as opposed to more general measures of social connection, because close relationships are a critically important aspect of one’s well-being. The quality of one’s close relationships are a key determinant of health (Farrell et al. 2018), with supportive relationships buffering against stress and having direct effects on well-being (Cohen and Willis 1985). We explore close relationships from a social psychology perspective, considering how self-compassion relates to one’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in these contexts (Fiske 2010). Given the importance of close relationships in promoting well-being, and given substantial evidence that self-compassion can be cultivated through intervention (Ferrari et al. 2019), a greater understanding of how self-compassion and close relationships may influence one another will offer potential targets for optimizing both individual and relational well-being.

We synthesize the data available on this topic using a scoping review methodology (Arksey and O’Malley 2005) as opposed to a systematic review, given that our primary goals are not related to answering a specific question that will inform policy or practice. Rather, we aim to identify and map the existing evidence in this field, including the extent of and gaps in knowledge (Munn et al. 2018), as a way to guide future research trajectories. This study aims to answer the following broad research question: Within the peer-reviewed literature, how is an individual’s self-compassion, as measured by two formats of the self-compassion scale, associated with current close relationship qualities, as measured by thoughts, feelings, or behaviors towards family members, romantic partners, friends, or others identified as “close”?

Methods

We followed the steps suggested by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) for conducting scoping reviews: (1) Identifying the research question (described above); (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

Search Strategy

After refining the research question, we identified relevant peer-reviewed studies by searching three online databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus. Articles were limited to those published from 2003 (when the first self-compassion scale was developed) (Neff 2003a, b) through June 2019. We limited articles to those written in English, human studies, and published in a peer reviewed journal. Searches included the combination of the following groups of key words or MeSH terms: (Self-compassion*) AND (“Parent-Child Relations”[Mesh] OR “Parenting”[Mesh] OR parenting[tw] OR parental[tw] OR parents[tw] OR parent[tw] OR mothers[tw] OR mother[tw] OR father[tw] OR fathers[tw] OR interpersonal[tw] OR dyad[tw] OR dyads[tw] OR dyadic[tw] OR relation*[tw]OR child*[tw] OR family[Mesh] OR family[tw] OR families[tw] OR familial[tw] OR sibling*[tw] OR brother*[tw] OR sister*[tw] OR husband[tw] OR wife[tw] OR marri*[tw] OR spous*[tw] OR couple*[tw] OR partner*[tw] OR significant other*[tw] OR household[tw] OR caregiver[tw] OR friends[Mesh] OR friend*[tw] OR attachment[tw] OR peer[tw] OR peers[tw] OR social[tw] OR relative*[tw]).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Following the scoping review methodology, we next selected studies that met inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were eligible for review if they examined self-compassion, as measured by the either the 26-item self-compassion scale (Neff 2003a, b) or its brief form (Raes et al. 2011) and any measure of the thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviors of a person whose self-compassion is measured towards another close individual or group of individuals with whom they currently interact (See Supplementary Table for a complete listing of all of the measures included.). We considered thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, three aspects commonly studied by social psychologists, to be highly inclusive for exploring how one is functioning within close relationships. We included studies that assessed hypothetical relationships (e.g., those which measured how one might behave if they had a current romantic partner). For the purpose of this review, close relationships included those with parents, children, siblings, families, romantic partners, significant others, and friends. Given our interest in attachment as a general measure of trust and belonging in close personal relationships, we included all measures of current attachment.

In addition, although there is recent debate in the self-compassion literature regarding the best way to measure self-compassion (Muris and Petrocchi 2017; Neff et al. 2019), we only included studies that reported findings using the above two self-compassion scales for three reasons: (1) the majority of studies to date utilize these scales; (2) the concept as described by Neff (2003a) necessitates the three components (self-kindness, common humanity and mindfulness) interacting dynamically as a system; and (3) it is yet unclear if using the subscales separately, or separating the subscales into the two factors of positive self-responding and negative self-responding, or simply using the positive self-responding items alone (all suggestions for defining and operationalizing self-compassion) represents the same or a different concept as that of Neff (Neff et al. 2017, 2019; Phillips 2019). For these reasons, we have chosen to use Neff’s conceptualization of self-compassion, and included only those studies that utilize the scales reflecting this conceptualization.

Furthermore, articles were excluded if they did not report self-compassion using the total score of the self-compassion scale, 26-item or 12-item versions (i.e., used a modified or subscale only version of the self-compassion scale); used an interpersonal measure that did not specify a close personal relationship (i.e., measure used vague terms like “others” or “peers”); were qualitative, case study, study protocol, editorials, review, or book review only; did not have any comparison between the self-compassion measure and the interpersonal measure (e.g., interventional studies that reported pre-post changes in measures only); used an interpersonal measure based on reflecting on past interactions only (e.g., memories of childhood relationships); used an interpersonal measure in a professional setting only (e.g., client-therapist, student-teacher); or used an interpersonal measure that is broad and/or not interactional (e.g., connection to community or society, social anxiety in a general context). Wherever possible, the actual measures used were obtained to verify that the scale items and instructions fit our definition of a close interpersonal measure.

Review Procedures and Data Abstraction

Two reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts for preliminary inclusion. Full texts were skimmed for those articles whose abstract did not provide enough information to determine the screening result. Those reviewers then independently reviewed the full-text version of all potentially relevant articles. Any articles that received conflicting ratings were discussed between the two reviewers. If agreement could not be reached, the article was presented to the full team (4 authors) for a discussion and final decision.

In step four of the scoping review process, studies that met final inclusion were extracted in order to allow comparison of the following: year of publication, country of origin, study design, overall study aims, study sample (including sample size, recruitment source, % male, race composition, and mean age), self-compassion scale used (26- or 12-item), close interpersonal measure(s) used, main findings relevant to this review, and study limitations.

The final step involved summarizing, collating, and reporting results. For ease of review, we organized results below thematically by close relationship type: family or parent-child, attachment, romantic, mixed close, or friendship.

Results

Summary of Included Studies

After removal of duplicates, the search returned 1,121 potentially relevant results. Three hundred fifty-three articles remained after title and abstract screening stage, and after full text review, a total of 72 articles met inclusion criteria. Some articles included multiple studies that met inclusion criteria, for a total of 81 studies. A PRISMA flowchart is provided in Fig. 1.

Of the 72 articles that met inclusion criteria, several contained more than one study, for a total number of 81 included studies. A total of 26,483 participants were assessed in these studies. Overall, participants were majority female (17,278; 65.2%) with an average age of 30.1 (for samples 18 years of age or older) and 14.4 (for samples 18 years of age and younger). Eight studies (3,739 participants) did not report enough data to calculate a mean age. The majority of studies were conducted in the USA (n = 36, 44%), followed by Portugal (n = 9, 11%), and the UK (n = 9, 11%); however, a wide breadth of countries were represented, including Iran (6 studies), Australia (4 studies), China (4 studies), and Korea (4 studies). Among the 36 US-based studies, 65.4% of participants identified as White, 9.9% as Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, or Hmong, 7.9% as Black or African-American, 6.8% as Hispanic or Latinx, 0.65% as Native American or Alaska Native, and 8.3% as “Other,” multiracial, or a non-reported racial/ethnic identity. Table 1 provides a summary of included study characteristics, including study designs and sample types. Overall, the majority of included studies were cross-sectional. Supplementary Table 1 provides a summary of the various interpersonal measures used in the included studies.

Self-Compassion, Family, and Parent-Child Relationships

Thirty-two studies measured self-compassion in the context of either family or parent-child relationships. The following results are organized first by relationship type (family versus specifically parent-child) and then, within the parent-child category, by whether self-compassion was measured in the child or in the parent.

Family Relationships

A number of studies explored how the quality and functioning of current family relationships are associated with one’s self-compassion, and how self-compassion mediated the relationship between family functioning and one’s well-being. Two studies examined college students’ level of family functioning using the Circumplex Model of cohesion and flexibility (Berryhill et al. 2018a). College students reporting higher levels of chaotic-enmeshment (fluid family roles and severe emotional dependency) had significantly lower self-compassion and higher anxiety. Meanwhile, students with cohesive (balanced involvement of family members in each another’s lives) and flexible (democratic decision-making) family functioning reported higher self-compassion and lower anxiety (Berryhill et al. 2018b). Self-compassion mediated the relationship between dysfunctional family relationships and student well-being. Thus, although dysfunctional family dynamics may lower college students’ level of self-compassion, authors conclude that increasing self-compassion may be helpful in improving mental health among the students.

Similarly, other studies in college-aged samples have confirmed that positive family factors including high relationship quality (Grevenstein et al. 2019), family functioning (Neff and McGehee 2010), and perceived family supportiveness (Hayes et al. 2016; Hood et al. 2020) are positively linked to self-compassion. Hayes et al. (2016) reported that high family supportiveness and low family distress are linked to higher self-compassion levels in a large sample of college students receiving mental health services. Likewise, in adolescent samples, higher levels of family cohesion (Jiang et al. 2016) and family functioning (Neff and McGehee 2010) are linked to higher self-compassion and youth well-being. Mediational analysis showed that self-compassion partially mediates the link between family functioning and youth wellbeing (Neff and McGehee 2010), suggesting self-compassion may be a useful intervention target for youth who come from dysfunctional family environments. However, in a sample of UK social work students, participants’ perception of the level of shame their families would feel if the participants had a mental health problem, which could be viewed as low perceived supportiveness, was unrelated to their self-compassion (Kotera et al. 2019).

Self-compassion has also been explored in the context of caring for family members with special needs. In parents caring for a child with autism, higher perceived support from their families was associated with higher self-compassion (Wong et al. 2016). Meanwhile, Lloyd et al. (2019) explored how self-compassion relates to coping strategies in family caregivers of people with dementia. A significant negative association was found between self-compassion and caregiver burden. Mediation analysis revealed that self-compassion had a significant negative indirect effect on burden via lower levels of dysfunctional coping. This result suggests that self-compassion may equip caregivers with coping skills to handle family caregiving demands.

Parent-Child Relationships, Parenting Behavior, and Child Self-Compassion

Numerous studies have explored how qualities of the parent-child relationship and parent behaviors relate to child self-compassion. While most studies hypothesized that the secure parent-child relationship may lead to child’s high self-compassion, one study explored the possibility of child self-compassion leading to relational well-being with their parents.

To begin, in two large cross-sectional studies in Portugal, secure attachment to parents (as measured by self-reported cognitive and affective experiences of trust, communication, and closeness with parents) was positively associated with adolescent self-compassion (Moreira et al. 2017, 2018). Path analyses revealed that secure parent-child attachment was positively associated with adolescent self-compassion, which was then positively associated with a multi-dimensional measure of adolescent well-being. Meanwhile, a study exploring a model of body appreciation in a large, all-female US college sample revealed a significant negative association between students’ anxious attachment to their mothers (characterized by worry about the availability of support) and self-compassion (Raque-Bogdan et al. 2016).

Several studies examining attachment to parents in adolescent and young adult samples have shown mixed or contrary findings. Jiang et al. (2017) examined attachment to mother and father in a sample of junior high school students in China. Trust, communication, and closeness attachment dimensions were examined separately. Controlling for child age and gender, adolescents’ closeness to mother and closeness to father each significantly predicted their self-compassion; however, parental trust and communication subscales were unrelated to child self-compassion. In contrast, there was no significant association between first-year college students’ attachment to parents and their self-compassion (Holt 2014).

Other studies explore how parents’ behavior or level of supportiveness relates to child self-compassion. Two studies in Portugal demonstrated that parent-reported mindful parenting (see below for a discussion mindful parenting, which entails high quality parenting behaviors) is positively linked to adolescents’ self-compassion (Gouveia et al. 2018; Moreira et al. 2018). Neff and McGehee (2010) reported that adolescents’ and young adults’ perceived supportiveness of their mothers was positively associated with their self-compassion. However, sexual minority high school students’ perceived parental support and monitoring was not related to their self-compassion (Hatchel et al. 2018).

Finally, Yarnell and Neff (2013) hypothesized that a child’s self-compassion may lead to higher levels of relational well-being. The study showed that young adults’ self-compassion was positively associated with greater relational well-being with both mothers and fathers. This relationship was mediated by their lower tendency to self-subordinate compared to compromise in conflicts with parents, which was considered a sign of healthy balance between their own needs and the needs of close others.

Parent Self-Compassion, Parent-Child Relationship, and Parenting Behaviors

Eleven studies examined the links between parent self-compassion and various measures of the parent-child relationship and/or parenting behaviors. Several of these used the self-report Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting scale (IM-P) (Duncan 2007; Duncan et al. 2009) to examine five dimensions related to adaptive caregiving skills and supportive parent-child interactions, which authors term “mindful parenting”: (1) listening to child with full attention, (2) emotional awareness of self and child, (3) self-regulation in the parenting relationship, (4) non-judgmental acceptance of self and child, and (5) compassion for self and child. Given the IM-P scale contains items examining a parent’s ability to compassionately relate to oneself during difficult situations with their child, it would be expected that the self-compassion scale would correlate with the IM-P. Indeed, several large cross-sectional studies with parents in Portugal and Korea have documented significant positive associations between parents’ self-compassion and mindful parenting using translated versions of the IM-P (Gouveia et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2019; Moreira et al. 2016; Moreira and Canavarro 2017).

Two cross-sectional studies examined how mothers’ attachment style with their own maternal figure is associated with their self-compassion and parenting outcomes. In both studies, maternal insecure attachment (i.e., anxious and avoidant subtypes) was negatively associated with maternal self-compassion (Moreira et al. 2015, 2016). Further, maternal attachment anxiety was negatively associated with mindful parenting indirectly via lower levels of maternal self-compassion (Moreira et al. 2016). In other words, mothers with attachment anxiety had decreased ability to parent mindfully possibly because of a lower level of self-compassion. Meanwhile, maternal attachment avoidance (characterized by emotional distance) was not significantly related to maternal self-compassion, but was negatively associated with mindful parenting. Using path analysis, another study examining 171 mother and school-aged child dyads reported that maternal insecure attachment was significantly negatively associated with maternal self-compassion, which was then strongly negatively associated with parenting stress (Moreira et al. 2015). These findings suggest that parenting challenges rooted in mothers’ insecure attachment histories may be improved through interventions targeting maternal self-compassion; however, differences between avoidant and anxious attachment subtypes may exist.

Meanwhile, only one study used an observational methodology, whereby parents and children are given instructions for an interactive task and parents’ behaviors are rated based on an established scale. This study of 38 parents in remission from recurrent depression rated the sensitivity (e.g., responsiveness to child’s bids for attention) of parents’ responses during several play tasks and found no significant association between parent self-compassion and their level of sensitivity (Psychogiou et al. 2016).

Another unique pair of studies in Iran examined attachment variables for women in the perinatal period. These studies found positive correlations between women’s self-compassion and her attachment to the fetus (Mohamadirizi and Kordi 2016) and newborn child (Kordi and Mohamadirizi 2018).

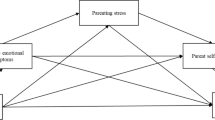

Other cross-sectional studies have reported how parent self-compassion relates to parenting stress, burden, and self-efficacy outcomes in both community-based and special needs populations. As mentioned above, Moreira et al. (2015) found significant negative associations between maternal self-compassion and parenting stress in a large, community-based normative sample of mothers of children aged 8–18 in Portugal. Another normative sample of 333 mothers and fathers (26.1% male) in Portugal reported that parent self-compassion had a significant negative relationship with parenting stress and a significant positive relationship with authoritative parenting style, a style considered positive and supportive (Gouveia et al. 2016). Furthermore, using path analysis, authors demonstrated that parent self-compassion was negatively indirectly associated with parenting stress via mindful parenting. This suggests that parents who have high self-compassion experience lower parenting stress due to their mindful parenting behaviors. Meanwhile, parent self-compassion was negatively associated with both parenting stress in parents of autistic children (Neff and Faso 2015), and with perceived burden in parents of adult children with intellectual disability (Robinson et al. 2017). Finally, a study of 23 parents of children with special needs showed a moderate but nonsignificant association (r = 0.34) between parent self-compassion and their parenting self-efficacy, described as how they view their capacity to meet the demands of parenting (Benn et al. 2012). There was also no significant relationship between parent self-compassion and their perceived quality of interaction with their child (Benn et al. 2012).

There is also evidence suggesting that parent self-compassion is linked to the way parents perceive their child’s behavior. Psychogiou et al. (2016) reported that parent self-compassion is linked to more adaptive thought patterns and coping within the parental context. Using semi-structured interviews, 38 parents with a history of recurrent depression were asked to imagine their 2- to 6-year-old child in various ambiguous behavior scenarios. While controlling for child gender, parent education, and depressive symptoms, there were significant associations between parent self-compassion and the tendency to attribute child behaviors to more transient, situation-related factors rather than fixed child characteristic-related factors.

A second longitudinal study by Psychogiou et al. (2016) examined parents’ (mixed community-based and depressed) critical versus positive comments about their child during a 5-min speech sample as well as self-reported typical responses to their child’s negative emotions. After controlling for child gender, parent education, and depressive symptoms, mothers’ self-compassion was significantly associated with fewer critical comments, while fathers’ self-compassion was significantly associated with fewer distressed and more problem-focused responses to their children’s negative emotions.

In summary, most evidence suggests that individuals who report higher functioning family relationships and secure attachment to their parent(s) have higher self-compassion. This relationship may be bidirectional, such that those with higher self-compassion function more adaptively within the family context. Nearly all these studies used self-report measures (rather than observed behaviors) and cross-sectional designs. For parents, high self-compassion is linked to supportive parenting behavior, less burden and stress, and better coping. Parent self-compassion may also help parents view their child’s behavioral difficulties in a more positive light. In turn, supportive parenting behavior is linked to higher self-compassion in the child.

Self-Compassion and Attachment

Twenty-five studies assessed the relationship between individuals’ general attachment styles in close relationships and their self-compassion. Of these, the majority of studies used various versions of the Experiences in Close Relationships measure (ECR) (Wei et al. 2007). In this scale, insecure attachment is represented by anxious and avoidant domains. Attachment anxiety is defined as those who tend to fear rejection or abandonment in close relationships, seek excessive approval, and feel distressed when support from others is unavailable. On the other hand, attachment avoidance involves a fear of dependency on close others, and as such, avoidant individuals tend to be self-reliant and emotionally distant in relationships. In addition, avoidant individuals often deny attachment needs and may under report difficulties with others.

Attachment anxiety and avoidance, as measured via the ECR, has been significantly negatively associated with self-compassion in a variety of samples including self-identifying gay men (Beard et al. 2017), community adults (Fuochi et al. 2018; Wei et al. 2011; Zhang and Chen 2017), community-dwelling older adults (Homan 2018), undergraduates from the USA (Huang and Berenbaum 2017; Øverup et al. 2017; Pepping et al. 2015; Raque-Bogdan et al. 2011; Wei et al. 2011), undergraduates in Korea (Joeng et al. 2017a), educators in Australia (Hwang et al. 2019), service-sector employees in Israel (Reizer 2019), clinically anxious and depressed adults (Mackintosh et al. 2017), and long-term breast cancer survivors (Arambasic et al. 2019).

Several studies did not report both anxious and avoidant attachment styles or had inconsistent findings. For example, in 132 trauma-experienced adults, attachment avoidance was significantly negatively associated with self-compassion (Bistricky et al. 2017); attachment anxiety was not measured. In a large undergraduate sample examining recalled bullying exposure, secure attachment was positively linked to self-compassion (Beduna and Perrone-Mcgovern 2019). However, in a study of 156 community adults in Israel examining how self-compassion relates to interpersonal orientations, self-compassion was significantly related to lower levels of attachment anxiety, but was not linked to attachment avoidance (Gerber et al. 2015).

Moreover, a number of these studies demonstrated that self-compassion mediates the relationships between attachment and a variety of health outcomes. For example, self-compassion mediated the relationships between insecure attachment and a multidimensional measure of health in older adults (Homan 2018) and workplace well-being (Reizer 2019). In undergraduate samples, self-compassion mediated relationships between attachment and various mental health outcomes (Joeng et al. 2017b; Raque-Bogdan et al. 2011), including measures of shame (Beduna and Perrone-Mcgovern 2019). Further, Mackintosh et al. (2017) demonstrated that avoidant attachment positively predicts emotional distress via lower self-compassion in a clinically anxious and depressed sample. These studies suggest that self-compassion may have a positive effect on emotional well-being in the context of insecure attachment.

A few studies found mixed results regarding self-compassion as a mediator between anxious and avoidant attachment and outcomes. Wei et al. (2011) investigated whether self-compassion mediated the relationships between both attachment insecurity subtypes and subjective well-being in two different samples. In this case, self-compassion was a significant mediator between anxious attachment and well-being for college student and community adult samples. However, results indicated that self-compassion mediated the relationship between avoidant attachment and well-being for community adults only. A study in a large university sample showed similar discrepant findings, whereby self-compassion significantly mediated paths between attachment anxiety and depressive symptoms, while the avoidant path was not significant (Øverup et al. 2017). Authors in both articles speculated that this finding is due to greater variability in self-views and self-compassion for avoidant individuals.

Meanwhile, some studies have explored alternative measures of attachment including the Relationship Questionnaire (Bartholomew and Horowitz 1991) and the Revised Adult Attachment Scale (Collins 1996). The Relationship Questionnaire uses two by two combinations of self-views (either positive or negative) and other-oriented views (either positive or negative) to create four categories regarding close relationships: secure (positive self-views and other-oriented views), preoccupied (negative self-views, positive other-oriented views), dismissive (positive self-views, negative other-oriented views), and fearful (negative self-views and other-oriented views). Self-views generally refer to the degree to which one feels worthy of love, while other-oriented views refer to the degree to which one is comfortable with emotional intimacy.

There are somewhat mixed findings regarding the correlations between self-compassion and the four attachment categories defined using the Relationship Questionnaire. For example, a study examining a clinical adult population of 128 individuals who hear voices reported that self-compassion was positively associated with secure attachment and negatively associated with fearful attachment, but not associated with preoccupied or dismissive categories (Dudley et al. 2018). Meanwhile, in two studies examining adult romantic partners (Neff and Beretvas 2013) and adolescent and college student samples (Neff and McGehee 2010), self-compassion was positively associated with secure attachment, negatively associated with both preoccupied and fearful attachment, and not associated with dismissive attachment. Additional mediational analysis for the combined sample revealed that self-compassion partially mediated the link between attachment styles (specifically secure, preoccupied, and fearful types) and a summary well-being measure, controlling for age and gender (Neff and McGehee 2010).

An interventional pilot study in Spain examined the effects of attachment-based compassion therapy (ABCT) in healthy adults compared with a waitlist control group (Navarro-Gil et al. 2020). The study measured active participants’ changes in attachment style as measured by the Relationship Questionnaire. Shifts from insecure to secure attachment, principally pre-occupied and dismissive types, were mediated through increases in self-compassion.

Finally, two studies explored attachment using the Revised Adult Attachment Scale. These studies showed negative associations between insecure attachment patterns and self-compassion in individuals receiving treatment for sex addiction (Kotera and Rhodes 2019) and in university students in Iran (Valikhani et al. 2018). However, while self-compassion mediated the relationship between student insecure attachment and measures of stress, anxiety, and depression (Valikhani et al. 2018), it did not mediate the relationship between insecure attachment and sex addiction (Kotera and Rhodes 2019).

In summary, using a wide variety of attachment measures and in varying populations, evidence shows that individuals who are securely attached in current close relationships tend to report high self-compassion. Likewise, insecure attachment in current close relationships is inversely linked with self-compassion; however, there is variability by attachment domain; the strongest links are evident for anxious attachment. The directionality of these associations cannot be assessed due to the cross-sectional designs of nearly all these studies. In addition, self-compassion may be an important mechanism by which attachment style impacts well-being outcomes.

Self-Compassion and Romantic Relationships

Seventeen studies examined self-compassion in the context of romantic relationships using a variety of sample types and interpersonal measures. To begin, four cross-sectional studies examined self-compassion and romantic partnership measures in couples experiencing health challenges. In women facing infertility, self-compassion was negatively correlated with self-reported infertility-related concerns and difficulties (e.g., difficulty talking about infertility) with their romantic partner (Raque-Bogdan and Hoffman 2015). In a study of women with chronic vulvovaginal pain and their romantic partners, self-compassion was unrelated to women’s relationship satisfaction. However, their partner’s self-compassion was significantly associated with the partner’s relationship satisfaction, even after controlling for pain duration and income (Santerre-Baillargeon et al. 2017). In couples facing lung cancer, patients’ self-compassion was significantly associated with better self-reported communication with their partner about the cancer (Schellekens et al. 2017). Finally, in a study examining dating behaviors in a sample of unpartnered breast cancer survivors, self-compassion was significantly negatively associated with dating anxiety and positively associated with a measure of interpersonal competence with a hypothetical romantic partner (Shaw et al. 2018). Self-compassion was not a significant predictor of dating anxiety when covariates were included in the model. However, self-compassion remained a significant predictor of interpersonal competence (a measure which included hypothetical relationship initiation, negative assertion, disclosure, emotional support, and conflict management). These studies suggest that self-compassion may be beneficial to how one relates to romantic partners in the context of managing health threats.

Self-compassion may also be linked to romantic relationship benefits outside of challenging health contexts. Jacobson et al. (2018) examined undergraduates in a relationship for at least 3 months and found that self-compassion was positively associated with both relationship satisfaction and dyadic adjustment, which includes concepts such as conflict resolution and cohesion. Self-compassion was significantly negatively associated with romantic partner attachment anxiety and mediated the relationship between attachment anxiety and body appreciation in a study of first year college women (Raque-Bogdan et al. 2016). Yarnell and Neff (2013) demonstrated that self-compassion was significantly associated with college students’ reports of higher relational well-being in current or former romantic relationships. In the context of conflict resolution, higher self-compassion was associated with increased likelihood to compromise with a romantic partner as opposed to either self-subordinate or self-prioritize. Moreover, the tendency to compromise partially mediated the association between self-compassion and relational well-being in romantic partnership conflicts. Finally, evidence suggests that after controlling for covariates such as relationship length and self-esteem, self-compassionate college students and community adults are more accepting of both their own and their romantic partner’s personal flaws (Zhang et al. 2020). Path analysis showed adult participants’ self-acceptance is positively linked to acceptance of their romantic partner, which is then positively linked to how accepted participants feel by their partner.

In adult samples, self-compassion has been positively associated with various measures of marital satisfaction and functioning in parents of children with autism (Shahabi et al. 2020) and Iranian couples (Maleki et al. 2019), and lower levels of jealousy in a jealousy-provoking context (Tandler and Petersen 2018). Mediation analysis further suggested that self-compassionate partners had lower levels of jealousy partly through greater willingness to forgive (Tandler and Petersen 2018). Neff and Beretvas (2013) reported that self-compassion was positively associated with relational well-being, which includes self-worth, positive affect, authenticity, and ability to self-express within the romantic relationship. Moreover, individuals who were high in self-compassion received higher positive relationship behavior ratings from their partners (e.g., they were perceived as more caring, accepting and autonomy-granting), lower negative relationship behavior ratings (e.g., they were perceived as less controlling, aggressive, and detached), and had partners who were more satisfied in the relationship.

A series of studies by Baker and McNulty (2011) suggested that self-compassion influences relationship behavior differentially depending on gender. For women, researchers found a positive main effect of self-compassion on motivation to correct an interpersonal mistake within a romantic relationship. In men, there was a moderation effect of self-compassion and conscientiousness. Men high in both self-compassion and conscientiousness reported higher levels of motivation to repair mistakes, while those high in self-compassion but low in conscientiousness reported lower levels of motivation to repair. This interaction effect was not significant for women.

A second study by Baker and McNulty (2011) in newlywed couples revealed no main effects of self-compassion on problem-solving behaviors during an observed conflict discussion in both women and men. However, similar to above findings, men high in self-compassion and conscientiousness were more likely to demonstrate constructive problem-solving behaviors, while those high in self-compassion but low in conscientiousness were less likely to demonstrate these behaviors.

Finally, Baker and McNulty (2011) followed a different sample of newlywed couples over the first five years of marriage to examine how self-compassion and conscientiousness may be associated with relationship satisfaction and severity of marital problems. For wives, self-compassion was associated with greater stability of marital satisfaction over time and less severe initial marital problems. For husbands, the association of self-compassion with changes in marital satisfaction and marital problem severity depended on level of conscientiousness. Authors summarize findings by noting that for women, self-compassion appeared to be beneficial to romantic relationship constructs. For men, the benefit of self-compassion depended on their level of conscientiousness.

In summary, evidence from primarily cross-sectional studies in various samples and contexts suggests that self-compassion is associated with adaptive romantic relationship qualities, including healthy conflict resolution behaviors, communication, acceptance of flaws, relationship satisfaction, and forgiveness. The directionality of these associations is unknown and may be reciprocal, and associations may depend on other factors such as gender and personality traits.

Self-Compassion and Mixed Close Relationships

Thirteen studies examined self-compassion in the context of close relationships, where the relationship measure indicated general “close relationships,” a combination of relationship types (e.g., support from family, friends, and significant others), or the analysis precluded separate findings by close relationship type.

Allen et al. (2015) conducted two experimental studies where participants were randomly assigned to scenarios where they “let down” another person, including close others. Participants were then asked how they typically would respond. Findings revealed that men high in trait self-compassion were more likely to use self-compassionate versus self-critical statements when discussing the incident with another person. For women, trait self-compassion was associated with a lower likelihood of self-critical responses but was not associated with self-compassionate responding. Authors suggest that self-compassion is associated with lower likelihood of outward expression of self-criticism in the context of repairing a mistake.

The second study by Allen et al. (2015) used similar measures, but in this case, the participants were “let down” by another person who was close to them. Participants were asked to rate their likelihood of forgiving the transgressor based on the content of their response. Findings revealed that those low in self-compassion preferred hearing self-critical statements by the transgressor. Meanwhile, participants high in self-compassion preferred to hear self-compassionate apologies and were equally likely to forgive the transgressor independent of the nature of their response. Authors suggest that people may prefer apologies that are consistent with their own self-attitudes.

Another study aimed to understand how self-compassion relates to emotional and behavioral responses to difficult interpersonal vignettes for persons with chronic pain (Purdie and Morley 2015). The vignettes corresponded with six situations with friends, family, and work colleagues and involved unpleasant self-relevant events (e.g., letting someone down). Independent of the relationship context, higher self-compassion was associated with affect responses that were less negative (less sadness, anxiety, anger, and embarrassment). Additionally, self-compassion was linked to lower likelihood of maladaptive coping responses (e.g., catastrophizing) in these interpersonal contexts.

A study in Israel explored how healthy adults’ self-attitudes, including self-compassion, related to their concern for others (Gerber et al. 2015). In reference to close relationships, self-compassion was inversely associated with pathological concern for others, or the denial of self-needs combined with the tendency to overinvest in others’ needs. Meanwhile, a second study reported that self-compassion was associated with lower rejection sensitivity, or lower concern about the outcome when making hypothetical requests from significant others, while controlling for positive and negative mood (Gerber et al. 2015).

Related to pathological relationships, a study of undergraduates examined self-compassion and early maladaptive schemas (Thimm 2017). The enmeshment subscale pertained to close interpersonal relationships, whereby participants were asked about feeling as if they do not have a separate identity from their parent(s) or partner. Results showed self-compassion was unrelated to the construct of enmeshment.

Another study explored how the quality of undergraduates’ relationships with close family members, friends, or romantic partners associated with self-compassion (Huang and Berenbaum 2017). The close others identified by participants were also asked to evaluate their view of the relationship with participants. Self-compassion was positively associated with a composite score for positive close relationship quality and negatively associated with negative close relationship quality, but unrelated to reports by close others regarding both positive and negative relationship quality evaluation. Meanwhile, in samples of sexual and gender minorities, self-compassion has been negatively linked to the frequency of negative social exchanges with close family or friends (Bell et al. 2019) and positively linked to the number of caring adults adolescent participants can rely on, excluding parents (Vigna et al. 2018).

Finally, several studies revealed that self-compassion was related to one’s perception of support from close others in challenging circumstances. In adults who have experienced serious trauma (Maheux and Price 2016), sexual minorities (Williams et al. 2017), and women in Iran with breast cancer (Alizadeh et al. 2018), self-compassion was positively associated with a composite measure of social support from family, friends, and significant others. In the trauma-experienced sample, perceived close other support was positively associated with self-compassion after controlling for age, gender, income, and multiple trauma exposure (Maheux and Price 2016). Meanwhile, a study examining parents of children with autism in China found that self-compassion was positively linked to a composite measure of perceived supportiveness from their friends and significant other (Wong et al. 2016). While self-compassion is consistently linked to perceived support, it is unclear if self-compassionate people perceive others in a more positive and supportive light, or if being supported by others increases one’s capacity for self-compassionate responding.

In summary, most studies examining “close others” showed that self-compassion is linked to relational benefits, including more adaptive responses to challenging interpersonal scenarios, higher levels of relationship quality, balanced concern for oneself and others, and higher perceived supportiveness of others. The directionality of these associations cannot be concluded.

Self-Compassion and Friendships

Finally, four studies found self-compassion to be linked to various friendship benefits. One longitudinal study involving college freshman examined self-compassion in the context of two types of friendship goals: self-image goals (goals related to obtaining and maintaining a positive social image) and compassionate goals (goals related to helping friends without expectation of self-benefit) (Crocker and Canevello 2008). Higher levels of self-compassion predicted higher average levels of compassionate friendship goals over the 10-week data collection period. Another study examined the association between self-compassion and methods of conflict resolution between best friends (Yarnell and Neff 2013). College students high in self-compassion reported higher relational well-being, were more likely to compromise as opposed to self-subordinate, and less likely to experience emotional turmoil when resolving conflicts with best friends. Lastly, self-compassion has been negatively associated with college students’ peer attachment anxiety (Raque-Bogdan et al. 2016) and adolescents’ perceptions of daily hassles with friends (Xavier et al. 2016). In all, these studies suggest that self-compassion and positive friendship qualities are positively linked.

Discussion

This review highlighted 72 articles (81 studies) with over 18,000 participants that examined self-compassion in the context of current family, parent-child, romantic, mixed close, and friend relationships. Overall, the body of literature reviewed suggests a positive association between an individual’s self-compassion and a wide range of factors relating to current close relationship health and functioning, with some notable gaps and caveats discussed below.

Qualities within the family environment, including level of supportiveness, cohesion, secure attachment, and parenting behaviors that are responsive to children’s emotions and needs, may play an important role in the development of child self-compassion. Meanwhile, parent self-compassion is linked to lower parenting stress (Gouveia et al. 2016), more adaptive thought patterns and coping in the context of parenting challenges (Psychogiou et al. 2016), and enhanced self-reported ability to be attentive and responsive towards their child (Moreira et al. 2016). Together, these findings suggest an intergenerational pattern of self-compassion development within families whereby parent self-compassion promotes supportive caregiving behaviors and the child’s secure attachment, which in turn fosters the child’s self-compassion. Therefore, parent self-compassion interventions have the potential to benefit both parent and child, and break cycles of dysfunction or insecure attachment.

There are areas where evidence is lacking regarding family self-compassion literature. First, only one study used behavior ratings of recorded parent-child interactions to more objectively assess parenting behavior. This study, although limited by small sample size, failed to find a significant association between parent self-compassion and sensitive responding during structured and unstructured play tasks (Psychogiou et al. 2016). To gain a better understanding of this line of research, observational studies with larger sample sizes are needed. Studies that observe and assess parents’ behavior in scenarios where the child is experiencing a difficult emotion or exhibiting challenging behavior may be helpful. These contexts may highlight specific patterns of behavior that distinguish between parents with high versus low self-compassion. Also, studies focus on pre-adolescent, adolescent, and college-aged participants and their mothers. To expand the field, studies that examine younger children and their observed interactions with fathers and families are needed. This approach permits a more comprehensive exploration of the role of parent self-compassion in the quality of caregiving behaviors, co-parenting and sibling relationships, and overall family climate.

Another promising area of investigation examines how parent self-compassion relates to thoughts about their child’s behavior. Psychogiou et al. (2016) reported that self-compassion in parents with a history of recurrent depression is related to the tendency to attribute child behaviors to more transient and situational causes rather than stable characteristics of the child. This finding links self-compassion to literature showing that parental attribution style, or how parents interpret caregiving events, is associated with parent, relationship, and child outcomes (Joiner and Dineen Wagner 1996). Given self-compassion has been linked to adaptive self-directed cognitions in response to difficult life events (e.g., Leary et al. 2007), it is plausible that self-compassion may also positively influence the way parents interpret their child’s challenges or weaknesses. Self-compassion training, therefore, may benefit parent attribution style, and may offer a method of intervening before maladaptive thoughts lead to harsh or unsupportive parenting behaviors.

Relatedly, there were consistently positive associations between secure attachment and self-compassion. These findings provide added support to the theory that healthy attachment relationships serve as a foundation for self-acceptance, emotion regulation, and self-worth (Shaver et al. 2016). Meanwhile, there was wide support in diverse populations for the inverse relationship between attachment insecurity and self-compassion, although significant associations were less consistent for avoidant (e.g., Gerber et al. 2015; Pepping et al. 2015; Wei et al. 2011) and dismissive attachment subtypes (Neff and McGehee 2010). This finding highlights the need for further investigation of how different attachment styles relate to self-compassion, and implications for close relationship quality.

Regarding self-compassion and romantic relationships, self-compassion appears to be largely associated with a host of adaptive characteristics in both health-stressed and general community samples. Aside from one study (Baker and McNulty 2011), all of these studies used self-report relationship ratings, highlighting the need for more objective measures of behavior and dyadic relationship quality. Moreover, only one study examined the moderating effect of a personality trait (i.e., conscientiousness) on the self-compassion-interpersonal health relationship (Baker and McNulty 2011). Authors found conscientiousness to be an important moderating factor for men but not women and suggested that self-compassion may, in certain circumstances, lead to decreased motivation to resolve relationship issues. Future studies should continue to explore gender and personality variables as moderators, as well as the potential relational downsides of self-compassionate tendencies.

Finally, findings from the literature on mixed close relationships and friendships also support the association between self-compassion and a wide variety of markers of relationship health. With one exception (Thimm 2017), the body of literature suggests that self-compassion promotes perspective taking and socially acceptable advocacy for one’s needs in close relationships (Gerber et al. 2015; Neff and Beretvas 2013; Yarnell and Neff 2013). Future studies should expand upon how the balancing of needs between oneself and close others may be beneficial, particularly for those experiencing caregiver burnout.

There are several strengths and limitations both to this study and to the body of literature reviewed. First, in following the scoping review methodology, we have provided a broad overview of the extant literature. However, we have not assigned quality ratings; thus, the studies included may have biases or methodological flaws that should be taken into consideration. This review does not provide conclusions, but rather offers a guide for future rigorous inquiries.

Relatedly, because most of the studies reviewed were cross-sectional, it is unclear if self-compassion precedes and promotes relationship benefits, if healthy relationships promote self-compassionate tendencies, or both. In order to examine these nuances, future research should include longitudinal study designs, cross-lagged analyses, interpersonal measures that include multi-informant and observed relationship measurements, and a bio-ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner 1979) that considers the many levels of influence on individuals and families (e.g., individual personality traits, peer, school and community factors). Additionally, more diverse age, race/ethnicity, male gender, and sexual minority samples are needed.

Finally, a recent meta-analysis shows that self-compassion can be increased through a wide variety of interventions (Ferrari et al. 2019). These interventions mainly assessed impact on individual level outcomes (e.g., depression, anxiety, life satisfaction). However, this review highlights the relevance of relational outcomes, and suggests that self-compassion may be an important mechanism by which relationship health impacts individual health. Therefore, self-compassion interventions that target individuals in challenging or stressed close relationships hold particular promise.

References

Alizadeh, S., Khanahmadi, S., Vedadhir, A., & Barjasteh, S. (2018). The relationship between resilience with self-compassion, social support and sense of belonging in women with breast cancer. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 19(9), 2469–2474. https://doi.org/10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.9.2469.

Allen, A. B., Barton, J., & Stevenson, O. (2015). Presenting a self-compassionate image after an interpersonal transgression. Self and Identity, 14(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2014.946958.

Arambasic, J., Sherman, K. A., & Elder, E. (2019). Attachment styles, self-compassion, and psychological adjustment in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 28, 1134–1141. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5068.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Baker, L. R., & McNulty, J. K. (2011). Self-compassion and relationship maintenance: The moderating roles of conscientiousness and gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(5), 853–873. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021884.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244.

Beard, K., Eames, C., & Withers, P. (2017). The role of self-compassion in the well-being of self-identifying gay men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 21(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2016.1233163.

Beduna, K. N., & Perrone-Mcgovern, K. M. (2019). Recalled childhood bullying victimization and shame in adulthood: The influence of attachment security, self-compassion, and emotion regulation. Traumatology, 25(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000162.

Bell, K., Rieger, E., & Hirsch, J. K. (2019). Eating disorder symptoms and proneness in gay men, lesbian women, and transgender and gender non-conforming adults: Comparative levels and a proposed mediational model. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2692. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02692.

Benn, R., Akiva, T., Arel, S., & Roeser, R. W. (2012). Mindfulness training effects for parents and educators of children with special needs. Developmental Psychology, 48(5), 1476–1487. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027537.

Berryhill, M. B., Harless, C., & Kean, P. (2018a). College student cohesive-flexible family functioning and mental health: Examining gender differences and the mediation effects of positive family communication and self-compassion. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 26(4), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480718807411.

Berryhill, M. B., Hayes, A., & Lloyd, K. (2018b). Chaotic-enmeshment and anxiety: The mediating role of psychological flexibility and self-compassion. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal, 40(4), 326-337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-018-9461-2.

Bistricky, S. L., Gallagher, M. W., Roberts, C. M., Ferris, L., Gonzalez, A. J., & Wetterneck, C. T. (2017). Frequency of interpersonal trauma types, avoidant attachment, self-compassion, and interpersonal competence: A model of persisting posttraumatic symptoms. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 26(6), 608–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1322657.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Cassidy, J. (2018). The nature of the child’s ties. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment (3rd ed., pp. 3–24). The Guilford Press.

Cohen, S., & Willis, T. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

Collins, N. L. (1996). Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(4), 810–832. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.4.810.

Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2008). Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.555.

Denckla, C. A., Consedine, N. S., & Bornstein, R. F. (2017). Self-compassion mediates the link between dependency and depressive symptomatology in college students. Self and Identity, 16(4), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2016.1264464.

Dudley, J., Eames, C., Mulligan, J., & Fisher, N. (2018). Mindfulness of voices, self-compassion, and secure attachment in relation to the experience of hearing voices. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12153.

Duncan, L. (2007). Assessment of mindful parenting among families of early adolescents: Development and validation of the Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting Scale (unpublished dissertation). Pennsylvania State University.

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent-child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3.

Farrell, A. K., Imami, L., Stanton, S. C. E., & Slatcher, R. B. (2018). Affective processes as mediators of links between close relationships and physical health. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12(7), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12408.

Ferrari, M., Hunt, C., Harrysunker, A., Abbott, M. J., Beath, A. P., & Einstein, D. A. (2019). Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness, 10(8), 1455–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01134-6.

Finlay-Jones, A. L. (2017). The relevance of self-compassion as an intervention target in mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review based on an emotion regulation framework. Clinical Psychologist, 21(2), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12131.

Fiske, S. (2010). Social beings: Core motives in social psychology (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons Inc..

Fuochi, G., Veneziani, C. A., & Voci, A. (2018). Exploring the social side of self-compassion: Relations with empathy and outgroup attitudes. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(6), 769–783. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2378.

Gerber, Z., Tolmacz, R., & Doron, Y. (2015). Self-compassion and forms of concern for others. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.052.

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018807.

Gouveia, M. J., Canavarro, M. C., & Moreira, H. (2018). Is mindful parenting associated with adolescents’ emotional eating? The mediating role of adolescents’ self-compassion and body shame. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02004.

Gouveia, M. J., Carona, C., Canavarro, M. C., & Moreira, H. (2016). Self-compassion and dispositional mindfulness are associated with parenting styles and parenting stress: The mediating role of mindful parenting. Mindfulness, 7, 700–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0507-y.

Grevenstein, D., Bluemke, M., Schweitzer, J., & Aguilar-Raab, C. (2019). Better family relationships––Higher well-being: The connection between relationship quality and health related resources. Mental Health & Prevention, 14, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mph.2019.200160.

Hatchel, T., Merrin, G. J., & Espelage, D. (2018). Peer victimization and suicidality among LGBTQ youth: The roles of school belonging, self-compassion, and parental support. Journal of LGBT Youth, 15(2), 134–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2018.1543036.

Hayes, J. A., Lockard, A. J., Janis, R. A., & Locke, B. D. (2016). Construct validity of the self-compassion scale-short form among psychotherapy clients. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 29(4), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2016.1138397.

Holt, L. J. (2014). Help seeking and social competence mediate the parental attachment–college student adjustment relation. Personal Relationships, 21(4), 640–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12055.

Homan, K. J. (2018). Secure attachment and eudaimonic well-being in late adulthood: The mediating role of self-compassion. Aging and Mental Health, 22(3), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1254597.

Hood, C. O., Thomson Ross, L., & Wills, N. (2020). Family factors and depressive symptoms among college students: Understanding the role of self-compassion. Journal of American College Health, 68(7), 683–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2019.1596920.

Howell, A. J., Dopko, R. L., Turowski, J. B., & Buro, K. (2011). The disposition to apologize. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(4), 509–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.05.009.

Huang, A. B., & Berenbaum, H. (2017). Accepting our weaknesses and enjoying better relationships: An initial examination of self-security. Personality and Individual Differences, 106, 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.031.

Hwang, Y.-S., Medvedev, O. N., Krägeloh, C., Hand, K., Noh, J.-E., & Singh, N. N. (2019). The role of dispositional mindfulness and self-compassion in educator stress. Mindfulness, 10, 1692–1702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01183-x.

Jacobson, E. H. K., Wilson, K. G., Solomon Kurz, A., & Kellum, K. K. (2018). Examining self-compassion in romantic relationships. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 8, 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.04.003.

Jiang, Y., You, J., Hou, Y., Du, C., Lin, M.-P., Zheng, X., & Ma, C. (2016). Buffering the effects of peer victimization on adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: The role of self-compassion and family cohesion. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.09.005.

Jiang, Y., You, J., Zheng, X., & Lin, M. P. (2017). The qualities of attachment with significant others and self-compassion protect adolescents from non suicidal self-injury. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000187.

Joeng, J. R., Turner, S. L., Kim, E. Y., Choi, S. A., Kim, J. K., & Lee, Y. J. (2017a). Data for Korean college students′ anxious and avoidant attachment, self-compassion, anxiety and depression. Data in Brief, 13, 316–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2017.06.006.

Joeng, J. R., Turner, S. L., Kim, E. Y., Choi, S. A., Lee, Y. J., & Kim, J. K. (2017b). Insecure attachment and emotional distress: Fear of self-compassion and self-compassion as mediators. Personality and Individual Differences, 112, 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.048.

Joiner, T. E., & Dineen Wagner, K. (1996). Parental, child-centered attributions and outcome: A meta-analytic review with conceptual and methodological implications. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01448372.

Kelly, A. C., & Dupasquier, J. (2016). Social safeness mediates the relationship between recalled parental warmth and the capacity for self-compassion and receiving compassion. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.017.

Kim, E., Krägeloh, C. U., Medvedev, O. N., Duncan, L. G., & Singh, N. N. (2019). Interpersonal mindfulness in parenting scale: Testing the psychometric properties of a Korean version. Mindulness, 10, 516–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0993-1.

Kordi, M., & Mohamadirizi, S. (2018). Neonatal-maternal attachment and self-compassion in postpartum period. Iranian Journal of Neonatology, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.22038/ijn.2018.25128.1327.

Kotera, Y., Green, P., & Sheffield, D. (2019). Mental health attitudes, self-criticism, compassion and role identity among UK social work students. British Journal of Social Work, 49, 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcy072.

Kotera, Y., & Rhodes, C. (2019). Pathways to sex addiction: Relationships with adverse childhood experience, attachment, narcissism, self-compassion and motivation in a gender-balanced sample. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 26, 54–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2019.1615585.

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Allen, A. B., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events : The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887.

Lloyd, J., Muers, J., Patterson, T. G., & Marczak, M. (2019). Self-compassion, coping strategies, and caregiver burden in caregivers of people with dementia. Clinical Gerontologist, 42(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1461162.

López, A., Sanderman, R., Ranchor, A. V., & Schroevers, M. J. (2018). Compassion for others and self-compassion: Levels, correlates, and relationship with psychological well-being. Mindfulness, 9(1), 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0777-z.

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003.

Mackintosh, K., Power, K., Schwannauer, M., & Chan, S. W. Y. (2017). The relationships between self-compassion, attachment and interpersonal problems in clinical patients with mixed anxiety and depression and emotional distress. Mindfulness, 9, 961–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0835-6.

Maheux, A., & Price, M. (2016). The indirect effect of social support on post-trauma psychopathology via self-compassion. Personality and Individual Differences, 88, 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.051.

Maleki, A., Veisani, Y., Aibod, S., Azizifar, A., Alirahmi, M., & Mohamadian, F. (2019). Investigating the relationship between conscientiousness and self-compassion with marital satisfaction among Iranian married employees. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8(76). https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_105_18.

Marsh, I. C., Chan, S. W. Y., & Macbeth, A. (2018). Self-compassion and psychological distress in adolescents — A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 9, 1011–1027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0850-7.

Marshall, S. L., Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P. D., & Sahdra, B. K. (2020). Is self-compassion selfish? The development of self-compassion, empathy, and prosocial behavior in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(S2), 472–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12492.

Marta-Simões, J., Ferreira, C., & Mendes, A. L. (2016). Self-compassion: An adaptive link between early memories and women’s quality of life. Journal of Health Psychology, 1359105316656771. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316656771.

Mohamadirizi, S., & Kordi, M. (2016). The relationship between multi-dimensional self-compassion and fetal-maternal attachment in prenatal period in referred women to Mashhad Health Center. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 5(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-9531.184550.

Moreira, H., & Canavarro, M. C. (2017). Psychometric properties of the interpersonal mindfulness in parenting scale in a sample of Portuguese mothers. Mindfulness, 8, 691–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0647-0.

Moreira, H., Carona, C., Silva, N., Nunes, J., & Canavarro, M. C. (2016). Exploring the link between maternal attachment-related anxiety and avoidance and mindful parenting: The mediating role of self-compassion. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 89(4), 369–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12082.

Moreira, H., Fonseca, A., & Canavarro, M. C. (2017). Assessing attachment to parents and peers in middle childhood: Psychometric studies of the Portuguese version of the People in My Life questionnaire. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(5), 1318–1333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0654-3.

Moreira, H., Gouveia, M. J., & Canavarro, M. C. (2018). Is mindful parenting associated with adolescents’ well-being in early and middle/late adolescence? The mediating role of adolescents’ attachment representations, self-compassion and mindfulness. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1771–1788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0808-7.

Moreira, H., Gouveia, M. J., Carona, C., Silva, N., & Canavarro, M. C. (2015). Maternal attachment and children’s quality of life: The mediating role of self-compassion and parenting stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(8), 2332–2344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0036-z.

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

Muris, P., & Petrocchi, N. (2017). Protection or vulnerability? A meta-analysis of the relations between the positive and negative components of self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(2), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2005.

Navarro-Gil, M., Lopez-del-Hoyo, Y., Modrego-Alarcón, M., Montero-Marin, J., Van Gordon, W., Shonin, E., & Garcia-Campayo, J. (2020). Effects of attachment-based compassion therapy (ABCT) on self-compassion and attachment style in healthy people. Mindfulness, 11, 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0896-1.

Neff, K. (2003a). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860390129863.

Neff, K. (2003b). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860390209035.

Neff, K. D., & Beretvas, S. N. (2013). The role of self-compassion in romantic relationships. Self and Identity, 12(1), 78–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2011.639548.

Neff, K. D., & Faso, D. J. (2015). Self-compassion and well-being in parents of children with autism. Mindfulness, 6(4), 938–947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0359-2.

Neff, K. D., & McGehee, P. (2010). Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self and Identity, 9(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860902979307.

Neff, K., & Pommier, E. (2013). The relationship between self-compassion and other-focused concern among college undergraduates, community adults, and practicing meditators. Self and Identity, 12, 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2011.649546.