Abstract

Objectives

Eating disorders are associated with significant physical, psychological, and social impairment, but existing treatments are effective only half of the time and relapse rates are high. Mindfulness-based programs (MBPs) are growing in empirical support and present a promising area of research to fill a crucial treatment gap for eating disorders. Several studies on MBPs for eating disorders show promising results, but overall the research on the use of mindfulness in eating disorder treatment is still lacking.

Methods

The goal of this theoretical paper is to present a rationale for why and how mindfulness may be helpful in the treatment of eating disorders.

Results

Several potential mechanisms by which MBPs may produce change in the eating disorder symptoms are presented: reduction in repetitive negative thinking and improvements in self-compassion, decentering, psychological flexibility, emotion regulation, and interoceptive awareness of hunger and fullness cues.

Conclusions

Research gaps and future directions for the study of mechanisms involved in MBPs for eating disorders are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Eating disorders are serious mental illnesses with the highest mortality rate of all psychological disorders (Arcelus et al. 2011). Significant physical and psychological impairments associated with eating disorders are compounded by treatment resistance and high rates of relapse (Keel et al. 2005). More research to improve the current state of eating disorder treatment is urgently needed. Mindfulness-based programs (MBPs) for other psychological conditions such as stress, anxiety, and depression have been gaining popularity and empirical support over the past 30 years (Goldberg et al. 2018). In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, MBPs were found to be superior to no treatment and equally effective to other evidence-based treatments for depression and anxiety (Goldberg et al. 2018). Furthermore, Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is a treatment of choice for preventing relapse in individuals with recurrent and treatment-resistant depression and MBPs outperformed other evidence-based treatments for smoking and other addictions in several trials (Goldberg et al. 2018, 2019; Kuyken et al. 2016).

Considering the success of MBPs in the treatment of other psychological conditions, it may also be a promising intervention for eating disorders, given that eating disorders are characterized by many of the same traits as these disorders (Fairburn et al. 2003). However, aside from a few studies testing MBPs for specific disordered eating behaviors, such as emotional eating and binge eating, the application of mindfulness to treatment of eating disorders has been limited (Warren et al. 2017). This trend could be at least partially explained by the lack of understanding of how mindfulness can be helpful in reducing eating disorder symptoms and concerns about appropriateness of these interventions for severe mental illness. Several mechanisms of action in MBPs for other psychological conditions have been identified (i.e., rumination, trait mindfulness, self-compassion), but it is unclear whether they generalize to eating disorders (Alsubaie et al. 2017; Gu et al. 2015).

The current theoretical paper aims to provide a rationale for why and how MBPs can be useful in the treatment of eating disorders and outline potential mechanisms of action to inform future research. This article is not intended to be an exhaustive literature review, but rather presents a conceptual framework to guide future research and treatment development. We will accomplish our goal in several steps. First, we will define eating disorders and mindfulness and provide a brief overview of existing MBPs for eating disorders. Second, we will describe research on existing mechanisms of action in MBPs for other psychological conditions and summarize theorized mechanisms for how mindfulness may produce change in eating disorder symptoms. Third, we will review existing evidence for each identified and hypothesized mechanism and provide justification for why it may or may not apply to the treatment of eating disorders. Finally, we will outline the proposed model integrating these mechanisms of action and discuss directions for future research stemming from this model.

Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are characterized by maladaptive behaviors and cognitions, such as food restriction, binge eating, purging, excessive exercise, overvaluation of weight and shape, and fear of weight gain. The three primary eating disorder diagnoses include anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge eating disorder (BED), but about 50% of individuals with eating disorders fall into other specified feeding and eating disorder (OSFED; Machado et al. 2007). Eating disorders affect individuals between 7 and 70 years old (Watson and Bulik 2014), and the lifetime prevalence of any eating disorder diagnosis is estimated to be 8.4% for women and 2.2% for men (Galmiche et al. 2019). AN is characterized by significantly low body weight due to restriction of food (reduction of energy intake) and other behaviors that prevent weight gain (i.e., exercise, self-induced vomiting, or laxative use), fear of weight gain, and overvaluation of weight and shape. BN is characterized by reoccurring episodes of binge eating (eating within 2-h period what most people would consider an unusually large amount of food and experiencing loss of control over eating) and purging (behaviors to prevent weight gain such as self-induced vomiting, fasting, or over-exercising) and overvaluation of weight and shape. BED is characterized by reoccurring episodes of binge eating associated with marked distress, but without any compensatory behaviors. OSFED diagnosis is given when eating-related behaviors cause a significant distress, but full criteria for one of the three above diagnoses are not met (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

Eating disorders are associated with significant physical, psychological, and social impairment, including potentially life-threatening medical complications (Westmoreland et al. 2016). Medical complications, high comorbidity rates (up to 90%), lack of awareness of illness, and low motivation to change make eating disorders very difficult to treat (Fassino and Abbate-Daga 2013; Hudson et al. 2007). Resistance to treatment is sometimes conceptualized as one of the symptoms of eating disorders, and treatment dropout rates reach 50–70% (Fassino et al. 2009). Some reasons for such high dropout rate and poor treatment engagement include unwillingness to gain weight (e.g., intense fear of weight gain) or accept a higher weight range and unwillingness to give up eating disorder as a coping strategy (Watson and Bulik 2014). Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders (CBT-E) is currently the treatment of choice for individuals with BN and BED but is effective only 50% of the time (Fairburn et al. 2009, 2015). Further, no empirically supported treatments exist for adults with AN. Even among individuals for whom treatment is effective, relapse rates for eating disorders are as high as 60% (Keel et al. 2005). More research is urgently needed to fill the eating disorder treatment gap. One form of treatment that is gaining traction both outside of eating disorders and within the eating disorder field are MBPs.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness was introduced to psychology by Kabat-Zinn (2013) who defined it as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” (p. 4). Mindfulness is a complex construct comprised of several aspects. State mindfulness refers to a temporary experience of being mindful and trait mindfulness is a disposition to act mindfully across different situations (Brown and Ryan 2003). Furthermore, the following facets are commonly examined: non-reactivity (letting thoughts and feelings come and go without getting caught up in them), acting with awareness (attending to present moment activities), observing (noticing sensory experiences), describing (labeling experiences such as sensations or cognitions with words), non-judgment (refraining from an evaluation of thoughts and feelings), and acceptance without judgment (refraining from applying evaluative labels such as good/bad or right/wrong, and to allow reality to be as it is without attempts to avoid, escape, or change it; e.g., Baer et al. 2004). In the context of psychotherapy, mindfulness is used to describe a psychological trait, a practice of cultivating mindfulness (e.g., mindfulness meditation), or a mode or state of awareness (Germer et al. 2005). Interventions that utilize mindfulness meditation have received strong empirical support for the treatment of depression, generalized anxiety, and stress (Alsubaie et al. 2017; Khoury et al. 2013) and showed preliminary support for treatment of substance use, social anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Boyd et al. 2018; Carroll and Lustyk 2018; Norton et al. 2015). The primary difference between MBPs and traditional cognitive-behavioral approaches is that instead of attempting to change the content of thoughts, the focus is placed on developing awareness and changing an individual’s relationship with thoughts (Beck 2011).

Mindfulness in the Treatment of Eating Disorders

Overview

Despite MBPs success with other psychological conditions, their use with eating disorders has been limited. Several MBPs for anxiety and depression, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn 1990) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal et al. 2013), have been adapted to treat binge eating disorder (BED) by increasing focus on eating practices, such as mindful eating (i.e., Bankoff et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2006). Mindful eating is a practice of eating slowly, without judgment or distraction, and focusing on sensory qualities of the food, such as smell, look, and taste (Courbasson et al. 2010). One of the first MBPs specifically designed for BED was conducted by Kristeller and Hallett (1999). Kristeller and Wolever (2010) developed mindfulness-based eating awareness training (MB-EAT) for BED, incorporating MBCT and MBSR traditions but focusing primarily on emotions and cognitions associated with binge eating. Later, a variety of mindfulness-based groups for BED emerged that combined a wide range of mindfulness and acceptance-based techniques (i.e., informal mindfulness and metaphors; Courbasson et al. 2010; Duarte et al. 2017). Additionally, dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) was adapted for treatment of BED and BN with good outcomes (Bankoff et al. 2012; Safer et al. 2001) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) showed preliminary support for treatment of AN (Juarascio et al. 2013). In this paper, DBT and ACT are not included when referring to MBPs because the primary interest is in mechanisms of action in MBPs with a strong mindfulness meditation component. Because DBT and ACT primarily focus on acceptance, informal mindfulness practices, and use of metaphors, mechanisms of action in these treatments may be different.

Theoretical Rationale

The theoretical rationale for using mindfulness to treat eating disorders is based primarily on the affect regulation model of eating disorders, which suggests that many eating disorder behaviors (i.e., binge eating, purging, and restricting) are methods to cope with negative affect (Corstorphine 2006; Lavender et al. 2014). From a mindfulness perspective, these behaviors may be considered a form of experiential avoidance and an attempt to find relief from negative emotional experiences that are perceived as uncontrollable (Baer et al. 2005). Mindfulness improves emotion regulation by teaching acceptance of emotions and increases tolerance of negative emotional states (Baer et al. 2005; Garland et al. 2017). Furthermore, mindfulness training helps individuals identify emotions as transient and non-threatening events that can be tolerated, which reduces the urge to avoid them by engaging in binge eating, purging, or restricting (Hepworth 2010). Some eating disorder presentations (i.e., AN) are characterized by poor awareness of emotional states and difficulty identifying feelings (i.e., alexithymia; Nowakowski et al. 2013). Mindfulness may help increase such emotional awareness (Baer et al. 2005).

Another common conceptual rationale for using MBPs for eating disorders is related to physiological sensations of hunger and fullness. Individuals with all eating disorders show disrupted awareness of hunger and fullness cues (Kissileff et al. 1996; Wierenga et al. 2015). It is hypothesized that long-term food restriction and binge eating lead to loss of awareness of natural appetite cues and individuals rely instead on external cues such as the presence of food, boredom, emotional, and social triggers (Lowe 1993). Lack of sensitivity to hunger may make it easier to avoid eating for long periods of time making it easier to restrict food intake. Disrupted fullness awareness may make it easier to ignore sensations of fullness and eat to the point of discomfort, which may lead to purging (Kristeller and Wolever 2010). Mindfulness practices, especially those specifically focused on hunger and fullness, are hypothesized to help individuals learn to recognize physiological cues of hunger and fullness and become less reactive to external triggers, such as the presence of food (e.g., Arch and Craske 2006).

Efficacy of MBPs for Eating Disorders

The majority of research testing MBPs for eating disorders focus on the treatment of BED. Across studies, researchers observed a significant reduction in binge eating episodes, binge eating symptoms, and overall eating disorder symptoms, including weight and shape concerns, restriction, body dissatisfaction, and fear of weight gain (i.e., Courbasson et al. 2010; Hepworth 2010; Pinto-Gouveia et al. 2016; Woolhouse et al. 2012). Research with non-clinical populations observed a reduction in food cravings, emotional eating, and external eating (eating triggered by being in proximity to food; i.e., Alberts et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2006, 2008). Several studies observed an increase in psychological flexibility and self-compassion (Duarte et al. 2017; Pinto-Gouveia et al. 2016), non-judgment (Baer 2006) and improved emotion regulation (Leahey et al. 2008). Only one study included participants with all of the three eating disorders (i.e., BED, BN, and AN) and found that there were no differences in outcomes by diagnosis (Hepworth 2010). To our knowledge, only two studies compared MBPs with other interventions. MB-EAT intervention was equally effective to cognitive-behavioral psychoeducation condition in reducing binge eating episodes in individuals with BED, but both performed better than the wait-list condition (Kristeller et al. 2014). MBSR was more effective than cognitive-behavioral-stress reduction program in reducing pain and increasing energy, but both conditions were equal in reducing binge eating episodes in a non-clinical population (Smith et al. 2008).

Although there is growing evidence for MBPs for eating disorders, a recent systematic review of third-wave behavioral therapies for the treatment of eating disorders found that no third-wave intervention currently meets the criteria for an empirically supported treatment (Linardon et al. 2017). The majority of symptom improvements seen in MBPs for BED are pre-post or compared with wait-list controls. However, when compared with other psychological interventions, MBPs do not outperform treatments as usual or cognitive behavioral interventions (Linardon et al. 2017). These results indicate that additional research is needed to improve and test MBPs for eating disorders, as well as expand its application to AN and BN. Although there is a theoretical rationale for using MBPs with all eating disorders (i.e., in addition to BED), very few studies have applied MBPs with these populations. Further, evidence suggests that MBPs are frequently used by clinicians in the treatment of eating disorders (at least as often as cognitive-behavioral therapy) as mindfulness gains more and more popularity in the psychotherapy field (Cowdrey and Waller 2015). Further investigation into how MBPs can benefit eating disorders and move these interventions towards meeting criteria of empirically supported treatments, potentially filling eating disorder treatment gap.

The paucity of research on MBPs for eating disorders may be at least partially explained by lack of understanding of how and why mindfulness may be helpful for an eating disorder. The clinicians may be ambivalent about using mindfulness with individuals with certain eating disorders, such as those with AN. One concern in using MBPs for individuals who are underweight, in starvation mode, or are severely depressed, is that mindfulness strategies may feel too aversive and reinforce desire to avoid thoughts and emotions possibly resulting in further restriction (Cowdrey and Park 2012). To our knowledge, no research has examined attitudes of individuals with eating disorders towards using mindfulness in their treatment. Although evidence shows that MBPs improve anxiety, depression, and stress by increasing individual’s trait mindfulness and self-compassion and reducing rumination, worry, and emotional avoidance (see section below for a detailed description of mechanisms of action), it is still unclear how MBPs may improve eating disorder symptoms. It would be reasonable to theorize that some mechanisms may generalize to eating disorders, but no theoretical model for the use of mindfulness in the treatment of eating disorders has been proposed. Such a theoretical model may help move forward research on MBPs for eating disorders and inform design of MBPs tailored for eating disorders. For example, if emotion regulation is identified as a mechanism, then mindfulness strategies that specifically target emotion regulation symptom should be included in treatment. This theoretical paper aims to propose a foundation for such a model.

Mechanisms of Action in Mindfulness-Based Programs for General Psychopathology

Mechanisms of action are defined as “the processes or events that are responsible for the change in therapy” (Kazdin 2007, p. 3). Mechanisms are identified primarily through the use of mediational analyses using longitudinal or experimental data (see Kazdin 2007 for a detailed description of criteria for mechanisms of action). Consistent with Kazdin’s recommendations, when discussing mediators, we will only be referring to the mediational analyses conducted in longitudinal treatment data; cross-sectional mediation analyses are not included. Mechanisms of action are usually studied after the efficacy of the treatment has been established to understand how the treatment works. However, understanding potential mechanisms of action is important in the initial process of treatment development and building a theory for why the treatment may work for a certain condition. Theoretically informed interventions produce better outcomes (Craig et al. 2008; Michie and Prestwich 2010).

Mechanisms of action of MBPs for psychological conditions other than eating disorders (i.e., anxiety, depression) have been extensively studied. Increases in trait mindfulness and self-compassion and decreases in rumination and worry have been identified as primary mechanisms of action in MBCT and MBRS (Alsubaie et al. 2017; Gu et al. 2015; van der Velden et al. 2015). Some studies identify increases in decentering or meta-cognitive awareness (ability to observe thoughts and feelings as mental events) and decreases in cognitive and emotional reactivity (the extent to which mild stressor activates negative thinking and emotional response) as mediators of MBPs (Alsubaie et al. 2017; Gu et al. 2015). Several other models of mechanisms of actions of MBPs have been proposed. For example, Shapiro et al. (2006) proposed that self-regulation, value clarification, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral flexibility, and exposure (extinction of fear of emotions) as mechanisms of action in MBPs. Emotion regulation is often theorized as one of the mechanisms of actions in MBPs (Chambers et al. 2009; Hölzel et al. 2011; Roemer et al. 2015). There are currently few methodologically rigorous studies testing the hypothesized mechanisms in statistical mediation analyses or experiments. Therefore, most of these proposed mechanisms do not yet meet criteria for a mechanism of action (see Kazdin 2007 for detailed criteria).

Mechanisms of Action in Mindfulness-Based Programs for Eating Disorders

The research on mechanisms of action in MBPs for eating disorders is scarce. Most studies discuss hypothesized mechanisms, but only one study specifically tested mediators of treatment change (Pinto-Gouveia et al. 2016). These researchers found that increases in psychological flexibility and self-compassion, reduction in body image cognitive fusion, and self-judgment mediated a decrease in binge eating; only psychological flexibility and non-reactivity mediated change in overall eating psychopathology (Pinto-Gouveia et al. 2016). Other hypothesized mechanisms of action of MBPs in eating disorders, in the order of being most frequently mentioned across studies, include increases in emotion regulation and distress tolerance, increases in awareness of physical sensation of hunger and fullness, and increases in psychological flexibility and decentering from weight and shape-related concerns. However, no theoretical model of how mindfulness may produce change in eating disorders has been proposed. A recent systematic review concluded that across all types of MBPs for binge eating, study outcomes were consistent with hypothesized mechanisms, but lack of proper study designs and statistical analyses (i.e., mediation) makes it difficult to make any conclusions about mechanisms of action (Barney et al. 2019).

Among hypothesized mechanisms of action in MBPs for eating disorders, several received empirical support in studies with other psychological disorders, such as trait mindfulness, psychological flexibility, self-compassion, and decentering. Non-reactivity is a facet of trait mindfulness, which was identified as a mechanism in MBCT and MBSR for depression and anxiety (Alsubaie et al. 2017; Gu et al. 2015). Psychological flexibility and self-compassion have some support as mechanisms in MBSR (Gu et al. 2015). Reduction in body image cognitive fusion is, in essence, decentering, which was identified as a mechanism in MBCT and MBSR (Alsubaie et al. 2017). Although there is plenty of evidence that mindfulness improves emotion regulation and distress tolerance (Chambers et al. 2009; Hölzel et al. 2011; Roemer et al. 2015), studies testing emotion regulation as a mediator in MBPs are lacking. There is a compelling theoretical foundation suggesting that emotion regulation may be one of the mechanisms in MBPs, and future research should test this theory. Rumination is not usually mentioned as one of the hypothesized mechanisms in eating disorder literature, but it may apply to eating disorders. Finally, increases in awareness of physical sensation of hunger and fullness may be an eating disorder-specific mechanism of action as it directly relates to eating behavior. See Table 1 for a description of each mechanism. In the following sections, we provide an overview of evidence for each mentioned mechanism. Specifically, we discuss all the mechanisms that have empirical support in MBPs for varied psychological conditions (trait mindfulness, self-compassion, rumination and worry, decentering, and psychological flexibility) and also those that are hypothesized in MBPs for eating disorders (emotion regulation and awareness of hunger and fullness cues).

Trait Mindfulness as a Mechanism

During MBPs, repeated mindfulness meditation practice contributes to the development of trait mindfulness (Kiken et al. 2015) by altering neurobiological activity (Hölzel et al. 2011). Recent systematic reviews found that MBCT and MBSR resulted in decreased anxiety, depression, and stress by increasing participants’ level of trait mindfulness (van Aalderen et al. 2012; Gu et al. 2015). Specifically, the mindfulness facets acceptance, non-reactivity, and acting with awareness received the most support as mechanisms of action (Batink et al. 2013; Labelle et al. 2015). Individuals with eating disorders have lower trait mindfulness than those without eating disorders, and trait mindfulness is inversely related to eating disorder symptoms (Adams et al. 2012; Butryn et al. 2013; Compare et al. 2012). Mindfulness facets that are most implicated in eating disorders are acting with awareness and non-reactivity. Two prospective studies found that non-reactivity inversely predicted bulimic symptoms, and lower acting with awareness predicted higher drive for thinness and bulimic symptoms over time (Sala and Levinson 2017; Sala et al. 2019b). In a residential treatment setting, higher levels of mindful acceptance predicted lower levels of eating disorder symptoms at discharge (Espel et al. 2016). One study found that non-reactivity facet of mindfulness mediated the effect of MBP on eating disorder symptoms (Pinto-Gouveia et al. 2016). Although more research is needed to determine if MBPs can increase levels of trait mindfulness in eating disorders, it is proposed to be one of the mechanisms of action in MBPs for eating disorders. Specifically, an increase in the acting with awareness facet of mindfulness may help individuals with eating disorders become more aware of maladaptive cognitions that drive eating disorder behaviors (i.e., thought “I am too full and will gain weight” leading to purging). Increases in the non-reactivity facet of mindfulness may allow inhibition of emotional and behavioral response to cognitions. Self-compassion may be useful in reducing shape- and weight-related self-judgments in EDs and interrupting the link between body dissatisfaction and ED behaviors by promoting body acceptance.

Reduction in Repetitive Negative Thinking as a Mechanism

Repetitive negative thinking is a transdiagnostic process defined as repetitive thinking focused on negative content that is difficult to control (Ehring and Watkins 2008). Two commonly identified forms of repetitive negative thinking are rumination and worry. The differences between these processes are that rumination is predominantly past oriented and worry is future oriented (Dar and Iqbal 2015; Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008). It is suggested that mindfulness helps individuals disengage from reflective repetitive negative thinking responses, about the past or future, and bring their attention to the present moment (Teasdale 2004). Rumination has strong empirical support as a mechanism of action in MBCT and MBSR for anxiety and depression (Alsubaie et al. 2017; Gu et al. 2015). Specifically, brooding rumination (focusing on negative symptoms), but not reflective thinking (contemplating symptoms to better understand or eliminate them) is implicated. Worry has also been identified as a mediator in several MBSR and MBCT, but less studies investigated worry (Batink et al. 2013; Labelle et al. 2015). These results suggest that the reduction in repetitive negative thinking, whether past or future oriented, is proposed to be a mechanism of action in MBPs.

Repetitive negative thinking is a salient feature of eating disorder psychopathology (Smith et al. 2018). Rumination and worry are associated with higher eating disorder symptoms (Naumann et al. 2015; Sternheim et al. 2012), and individuals with eating disorders have higher rates of both rumination and worry than controls (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2007; Rawal et al. 2010). Longitudinal studies show that rumination and worry predict higher eating disorder symptoms over time (Holm-Denoma and Hankin 2010; Sala et al. 2019a; Sala and Levinson 2016). Repetitive negative thinking is often considered to be a maladaptive coping strategy (Nolen-Hoeksema 2000). Specifically, in individuals with eating disorders, a rumination style of coping increases body dissatisfaction and negative mood (Svaldi and Naumann 2014). Additionally, individuals with eating disorders experience high levels of eating disorder-specific rumination and worry related to food, weight control, and body shape (Rawal et al. 2010; Seidel et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2017). Overall, based on this evidence, reduction in repetitive negative thinking as a mechanism of action in MBPs is proposed to generalize to eating disorders. A reduction in rumination and worry may lower depression and anxiety frequently associated with eating disorders. A decrease in repetitive negative thinking about body shape and weight may lower their impact on one’s self-worth and reduce body dissatisfaction (Svaldi and Naumann 2014). Lower rumination and worry about eating and food may reduce shame and anxiety associated with eating and, thus, lead to less compensatory behaviors and restriction.

Self-Compassion as a Mechanism

Self-compassion is a multifaceted construct that includes three components: practicing kindness to oneself instead of criticism and judgment, seeing one’s experience as part of common human experience rather than isolating, and maintaining awareness of negative thoughts and feelings without avoiding them or overidentifying with them (Neff 2003). Neff (2003) states that although cultivation of mindful attitude is necessary for developing self-compassion, they are separate psychological constructs. A systematic review by Gu et al. (2015) initially identified only preliminary support for self-compassion as mediator in MBSR and MBCT (Keng et al. 2012; Kuyken et al. 2010). Since then, several other studies emerged supporting self-compassion as a mechanism of action in MBSR and other MBPs (Gu et al. 2017; Ștefan et al. 2018; Takahashi et al. 2019). Overall, there is evidence supporting self-compassion as mechanism of action in mindfulness interventions, even without specifically targeting self-compassion. Some suggest that self-compassion is one of the outcomes of mindfulness practice (Bishop et al. 2006; Brown et al. 2007).

Individuals with eating disorders have lower levels of self-compassion than control samples (Ferreira et al. 2013), and self-compassion is inversely associated with eating disorder pathology (Fresnics et al. 2019). Self-compassion may be particularly relevant to constructs related to body dissatisfaction, as it is negatively associated with shape and weight concerns, body preoccupation, eating guilt, and overall eating disorder symptoms in both clinical and non-clinical samples (Ferreira et al. 2013). Several self-compassion interventions have been tested in clinical eating disorder samples resulting in an increase in self-compassion and decrease in body dissatisfaction and overall eating disorder symptoms (Albertson et al. 2015; Kelly and Carter 2015; Pinto-Gouveia et al. 2016). Further, increased self-compassion early in treatment predicted a greater decrease in eating disorder symptoms (Kelly et al. 2014). Body dissatisfaction was found to predict future eating disorder symptoms in individuals with low self-compassion, but not those high in self-compassion (Stutts and Blomquist 2018). Regarding mechanisms of action, one study found that self-compassion mediated the effect of MBP on binge eating (Pinto-Gouveia et al. 2016). Considering these results, it is proposed that self-compassion may be a mechanism in MBPs for eating disorders. Self-compassion may be useful in reducing shape- and weight-related self-judgments in eating disorders and interrupt the link between body dissatisfaction and eating disorder behaviors by promoting body acceptance.

Decentering as a Mechanism

Decentering refers to the ability to recognize and observe thoughts and emotions as temporary psychological events rather than true descriptions of reality (Safran and Segal 1990). Decentering is also sometimes referred to as metacognitive awareness (Teasdale et al. 2002) and is closely related to diffusion (Hayes et al. 1999) and reperceiving (Shapiro et al. 2006). It is suggested that repeated mindfulness meditation practice leads to the increase of decentering ability (Carmody et al. 2009). We are aware of only one study that tested decentering as a mediator of MBP. Hoge et al. (2015) found that decentering mediated the effect of MBSR on generalized anxiety symptoms. Other studies found that increase in decentering and meta-cognitive awareness was associated with symptom improvement in MBPs (Hargus et al. 2010).

Little research exists on the relationship between decentering and eating disorders. Several studies found that decentering ability was significantly negatively associated with eating disorder symptoms (Mendes et al. 2017; Palmeira et al. 2014). Future research should examine longitudinal relationship between decentering and eating disorder symptoms. Although limited evidence is available, decentering has potential to be one of the mechanisms of action in MBPs for eating disorders. Decentering skills may help individuals with eating disorders see their body and food-related cognitions and emotions as transient events in their mind rather than reality. For example, decentering may help individuals recognize the thought “I ate too much food” as a thought that will pass instead of a fact that necessitates behavioral response.

Psychological Flexibility as a Mechanism

Psychological flexibility is defined as the ability to remain in the present moment and accept arising thoughts and emotions while engaging in behaviors consistent with one’s values (Hayes et al. 2006). A few studies found psychological flexibility to be a mediator of MBPs’ effect on stress, mood, and anxiety (Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia 2017; Labelle et al. 2015). Psychological flexibility is at the center of the conceptual theory of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and is considered to be a core mechanism of action (Stockton et al. 2019). Both mindfulness and psychological flexibility foster present moment awareness and non-attachment to thoughts and emotions (Hayes et al. 1999). Therefore, it is probable that psychological flexibility may be one of the mechanisms of action in MBPs.

Psychological flexibility is inversely associated with eating disorder symptoms (Masuda and Latzman 2012). Merwin 2011suggested that high need to attend to emotional and body-related experiences drives eating disorder behaviors and improvements in psychological flexibility may help these individuals detach from these experiences and engage in value-driven action. Treatments that target psychological flexibility were shown to reduce eating disorder symptoms (i.e., Juarascio et al. 2013). Additionally, body image psychological flexibility has been studied in the context of eating disorders. Body image psychological flexibility refers to engaging in value-driven behaviors in the presence of distressing internal experiences related to body dissatisfaction (Sandoz et al. 2013). Body image psychological flexibility is associated with greater body acceptance and lower eating disorder pathology and predicted lower eating disorder symptoms in patients with eating disorders at discharge from residential treatment center (Bluett et al. 2016). One study found that increases in psychological flexibility mediated the effect of MBP on eating disorder symptoms (Pinto-Gouveia et al. 2016). Overall, the evidence for psychological flexibility as a mechanism of action in MBPs for eating disorders is preliminary, but promising. Psychological flexibility could facilitate following treatment recommendations. For example, eating a meal despite feeling fat or guilty because individual values being healthy and recovering to spend more time with family.

Emotional Regulation as a Mechanism

Emotion regulation is a multifaceted construct with heterogeneity of definitions. Broadly, emotion regulation refers to a variety of strategies that can be implemented at different times, from when emotions arise to when they are experienced and expressed (Goldin and Gross 2010). Mindfulness may (a) help build awareness and acceptance of emotions, (b) let go of judgmental evaluations of emotions as good and bad, (c) increase the ability to engage in valued action in the presence of distressing emotions (similar to psychological flexibility), (d) inhibit impulsive behaviors (similar to non-reactivity facet), (e) enhance the ability to tolerate, and (f) willingness to experience negative emotions as a part of life (Gratz and Tull 2010). The latter is referred to as distress tolerance, which is a dimension of emotion regulation (Gratz and Roemer 2004). Although there is wealth of evidence that mindfulness meditation improves emotion regulation (Chambers et al. 2009; Hölzel et al. 2011; Roemer et al. 2015), very few studies have examined emotional regulation as a mediator of MBPs using longitudinal data. One study found evidence to suggest that increased attentional control from mindfulness training leads to less reactivity, which in turn results in better emotion regulation via cognitive reappraisal, and subsequently increases positive affect (Garland et al. 2017). An experimental study found that participants who completed a short breathing exercise experienced significantly less negative affect viewing negative slides than those who were instructed to worry or focus their attention on nothing in particular (Arch and Craske 2006). Neuroimaging studies show that mindfulness training reduces reactivity in brain regions responsible for emotional response (Guendelman et al. 2017; Kral et al. 2018).

Emotion dysregulation is a core feature of eating disorders and individuals with eating disorders report higher levels of emotion regulation difficulties compared with controls (Mallorquí-Bagué et al. 2018; Pisetsky et al. 2017). Additionally, the severity of eating pathology is associated with emotion regulation difficulties (Svaldi et al. 2012). The cognitive-behavioral model of eating disorders identifies mood intolerance (i.e., low distress tolerance) as one of the risk factors for developing an eating disorder (Fairburn et al. 2003). Indeed, Lampard et al. (2011) found that individuals with eating disorders showed intolerance of both negative and positive affect. All eating disorders are sometimes conceptualized as disorders of emotion dysregulation, and binge eating, purging, and restricting are considered maladaptive and ineffective ways to regulate negative affect (Merwin 2011). Treatments targeting emotion regulation difficulties in eating disorders (i.e., dialectical behavioral therapy [DBT]) show good outcomes (Godfrey et al. 2015; Haynos et al. 2016). Overall, emotion regulation (and the distress tolerance aspect specifically) is proposed to be one of the mechanisms of action in MBPs for eating disorders. Future research should test emotion regulation as a mediator in MBPs. Reduced emotional reactivity to triggers and ability to effectively regulate and tolerate emotions may reduce the need to engage in eating disorder behaviors, such as binge eating, purging, restricting, excessive exercising, and body checking.

Awareness of Hunger and Fullness as a Mechanism

Increased awareness of physical sensations of hunger and fullness is at the core of the theoretical rationale for using mindfulness in the treatment of eating disorders (Kristeller and Wolever 2010), but to our knowledge, it has not been examined as a potential mechanism of action. Some evidence exists that mindfulness meditation increases awareness of hunger and fullness cues beyond solely improving eating outcomes (Beshara et al. 2013; Hong et al. 2014; Kristeller et al. 2014). Sensations of hunger and fullness, along with other bodily sensations such as heartbeat, body temperature, and pain are part of interoceptive awareness, which has been more extensively studied. Interoceptive awareness is described as the processes of perception and interpretation of internal signals relating to body states (Khalsa and Lapidus 2016). Formal mindfulness practices aim to purposefully bring attention to interoceptive sensations and increase body awareness (i.e., body scan). MBPs were shown to improve interoceptive sensitivity across a variety of physical and psychological conditions (Bornemann et al. 2015; Fischer et al. 2017; Fissler et al. 2016). Individuals with eating disorders have marked deficits in interoceptive awareness (Brown et al. 2017; Khalsa et al. 2015). One study found that interoceptive awareness had an indirect effect on the relationship between mindfulness and eating disorder symptoms above and beyond emotion dysregulation (Lattimore et al. 2017). To our knowledge, no studies, however, examined interoceptive awareness as a mediator in MBPs. Considering the preliminary evidence, improvements in interoceptive awareness of hunger and fullness cues may be one of the mechanisms of action in MBPs for eating disorders. Better awareness of physiological sensations of hunger may help individuals with eating disorders eat intuitively rather than relying on rules, urges, or external triggers and re-learn how to guide food intake based on body’s needs rather than dieting rules.

Discussion

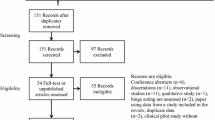

MBPs are gaining popularity in the treatment of eating disorders, but none currently meet criteria of evidence-based treatments. However, MBPs represent a potentially promising solution to fill the treatment gap in eating disorders. Although research on the use of mindfulness for other psychological conditions is flourishing, the field of eating disorders trails behind. Describing the rationale for how mindfulness may be useful in treating eating disorders and providing a theoretical model of potential mechanisms of action may help stimulate additional research in this area. In an effort to provide a foundation for such model, we have examined evidence for hypothesized mechanisms of action in MBPs for eating disorders and how known mediators of MBPs in other psychological disorders may generalize to eating disorders. Overall, we identified seven potential mechanisms of action with various levels of empirical support: reduction in repetitive negative thinking and improvements in self-compassion, decentering, psychological flexibility, emotion regulation, and interoceptive awareness of hunger and fullness cues. See Fig. 1 for an illustration of our theorized model.

The model shows that reduction in repetitive negative thinking and improvements in trait mindfulness, self-compassion, decentering, psychological flexibility, emotion regulation, and interoceptive awareness of hunger and fullness cues may partially or fully mediate the effect of MBPs on improvement in eating disorder symptoms. First, two facets of trait mindfulness, non-reactivity and acting with awareness, may be particularly relevant to eating disorders. Increases in acting with awareness may help individuals with eating disorders become more aware of maladaptive cognitions that drive eating disorder behaviors (i.e., thought “I am too full and will gain weight” leading to purging), and increases in non-reactivity may allow them to inhibit the emotional and behavioral response to such thought. Second, a reduction in rumination and worry may lower depression and anxiety frequently associated with eating disorders. Additionally, a decrease in repetitive negative thinking about body shape and weight may lower their impact on one’s self-worth and reduce body dissatisfaction. Third, self-compassion may be useful in reducing shape- and weight-related self-judgments in eating disorders and interrupt the link between body dissatisfaction and eating disorder behaviors by promoting body acceptance. Fourth, decentering skills may help individual with eating disorders see their body and food-related cognitions and emotions as transient events in their mind rather than reality. Fifth, psychological flexibility may help facilitate following treatment recommendations, such as adhering to a meal plan despite negative thoughts and emotions. Sixth, reduced emotional reactivity to triggers and ability to effectively regulate and tolerate emotions may reduce the need to engage in eating disorder behaviors, such as binge eating, purging, restricting, excessive exercising, and body checking. Finally, interoceptive awareness of hunger and fullness cues may be an eating disorder-specific mechanism that helps individuals with eating disorders regulate their eating based on the needs of their body. Future research should test if this model fully or partially explains how MBPs may be helpful in treating eating disorders.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current theoretical paper has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First and foremost, we have attempted to provide a complete and up-to-date overview of the literature on the topics, but we have not conducted a systematic review of the literature. Therefore, it is possible that some studies may have been omitted, including those that do not support our proposed mechanisms of action. The proposed model has been formulated based on prior research and has not been empirically tested. We hope that development of this model will lead to future research. Third, the model of mechanisms of actions in MBPs for eating disorders proposed here is meant to lay a foundation for future research and we do not claim that it fully explains how mindfulness works in the treatment of eating disorders. Only some mechanisms (reduction in repetitive negative thinking and improvements in trait mindfulness, self-compassion, and decentering) have empirical support and the rest are hypothesized based on limited available research. Further, the hypotheses are based primarily on correlational and treatment studies, whereas experimental studies are required to establish true causal effect (Kazdin 2007). At this time, we are not able to suggest whether each proposed mechanism makes a unique contribution to change in MBPs or if some overlap exists. It is also not clear whether the proposed mechanisms would function concurrently or whether one occurs before the other (i.e., increase in decentering before improvement in emotion regulation). Moreover, other mechanisms, not mentioned in this paper, may be relevant in MBPs for eating disorders. For example, we did not consider neurological mechanisms of MBPs (Hölzel et al. 2011). Lastly, this model may not apply to all eating disorder diagnoses.

This paper presents a preliminary model of how and why MBPs may be effective at treating eating disorders to inform future research. Additionally, we identified several gaps in the literature that should be addressed. Increases in trait mindfulness and self-compassion and reduction in repetitive negative thinking were separately identified as mechanisms of action in MBPs, but it is not clear whether they occur simultaneously. Future research should examine whether an increase in trait mindfulness as a result of meditation practice leads to reduced repetitive negative thinking and increased self-compassion. Although research shows that repetitive negative thinking is a salient feature of eating disorder psychopathology, future studies should test whether interventions focused on decreasing repetitive negative thinking lead to the reduction of eating disorder symptoms. Similarly, more research on self-compassion interventions for eating disorders is needed. Although decentering and psychological flexibility are clearly important in the process of MBPs, very little is known about their potential role in eating disorder treatment. More research is needed to examine whether increased awareness of hunger and fullness cues corresponds with improvements in eating disorder symptoms in MBPs. Another question to be answered is whether mindfulness meditation or mindful eating on their own is sufficient for a change in eating disorder symptoms or if they need to be combined.

To gather further support for the proposed model, experimental studies can be useful to establish causal links between MBPs and proposed mechanisms and between mechanisms and eating disorder outcomes. fMRI scans done before and after mindfulness exercise can help illuminate the neurological processes of emotion regulation. Additionally, brief mindfulness induction in an experimental setting may not be sufficient to induce changes in outcomes. Future research should use mediational analyses to examine if reduction in repetitive negative thinking and improvements in trait mindfulness, self-compassion, decentering, psychological flexibility, emotion regulation, and interoceptive awareness of hunger and fullness cues mediate the effect of MBPs on eating disorder symptoms independently and in a combined model. The latter will help clarify if each mechanism contributes to the process of change individually or if their effects overlap. We hope that future research testing the proposed model helps improve MBPs for eating disorders and potentially help fill the eating disorder treatment gap.

References

Adams, C. E., McVay, M. A., Kinsaul, J., Benitez, L., Vinci, C., Stewart, D. W., & Copeland, A. L. (2012). Unique relationships between facets of mindfulness and eating pathology among female smokers. Eating Behaviors, 13(4), 390–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.05.009.

Alberts, H. J. E. M., Thewissen, R., & Raes, L. (2012). Dealing with problematic eating behaviour. The effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on eating behaviour, food cravings, dichotomous thinking and body image concern. Appetite, 58(3), 847–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.009.

Albertson, E. R., Neff, K. D., & Dill-Shackleford, K. E. (2015). Self-compassion and body dissatisfaction in women: A randomized controlled trial of a brief meditation intervention. Mindfulness, 6(3), 444–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0277-3.

Alsubaie, M., Abbott, R., Dunn, B., Dickens, C., Keil, T. F., Henley, W., & Kuyken, W. (2017). Mechanisms of action in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in people with physical and/or psychological conditions: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 55, 74–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2017.04.008.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., & Nielsen, S. (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724–731. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74.

Arch, J. J., & Craske, M. G. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness: Emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(12), 1849–1858. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BRAT.2005.12.007.

Baer, R. A. (2006). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg015.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: The Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment, 11(3), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191104268029.

Baer, R. A., Fischer, S., & Huss, D. B. (2005). Mindfulness and acceptance in the treatment of disordered eating. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 23(4), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-005-0015-9.

Bankoff, S. M., Karpel, M. G., Forbes, H. E., & Pantalone, D. W. (2012). A systematic review of dialectical behavior therapy for the treatment of eating disorders. Eating Disorders, 20(3), 196–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2012.668478.

Barney, J. L., Murray, H. B., Manasse, S. M., Dochat, C., & Juarascio, A. S. (2019). Mechanisms and moderators in mindfulness- and acceptance-based treatments for binge eating spectrum disorders: A systematic review. European Eating Disorders Review, 27(4), 352–380. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2673.

Batink, T., Peeters, F., Geschwind, N., van Os, J., & Wichers, M. (2013). How does MBCT for depression work? Studying cognitive and affective mediation pathways. PLoS One, 8(8), e72778. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072778.

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Beshara, M., Hutchinson, A. D., & Wilson, C. (2013). Does mindfulness matter? Everyday mindfulness, mindful eating and self-reported serving size of energy dense foods among a sample of South Australian adults. Appetite, 67, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPET.2013.03.012.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2006). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077.

Bluett, E. J., Lee, E. B., Simone, M., Lockhart, G., Twohig, M. P., Lensegrav-Benson, T., & Quakenbush-Roberts, B. (2016). The role of body image psychological flexibility on the treatment of eating disorders in a residential facility. Eating Behaviors, 23, 150–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.10.002.

Bornemann, B., Herbert, B. M., Mehling, W. E., & Singer, T. (2015). Differential changes in self-reported aspects of interoceptive awareness through 3 months of contemplative training. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1504. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01504.

Boyd, J. E., Lanius, R. A., & McKinnon, M. C. (2018). Mindfulness-based treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of the treatment literature and neurobiological evidence. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 43(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.170021.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701598298.

Brown, T. A., Berner, L. A., Jones, M. D., Reilly, E. E., Cusack, A., Anderson, L. K., Kaye, W. H., & Wierenga, C. E. (2017). Psychometric evaluation and norms for the multidimensional assessment of interoceptive awareness (MAIA) in a clinical eating disorders sample. European Eating Disorders Review, 25(5), 411–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2532.

Butryn, M. L., Juarascio, A., Shaw, J., Kerrigan, S. G., Clark, V., O’Planick, A., & Forman, E. M. (2013). Mindfulness and its relationship with eating disorders symptomatology in women receiving residential treatment. Eating Behaviors, 14(1), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EATBEH.2012.10.005.

Carmody, J., Baer, R. A., Lykins, E., & Olendzki, N. (2009). An empirical study of the mechanisms of mindfulness in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(6), 613–626. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20579.

Carroll, H., & Lustyk, M. K. B. (2018). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance use disorders: Effects on cardiac vagal control and craving under stress. Mindfulness, 9(2), 488–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0791-1.

Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2009.06.005.

Compare, A., Callus, E., & Grossi, E. (2012). Mindfulness trait, eating behaviours and body uneasiness: A case-control study of binge eating disorder. Eating and Weight Disorders, 17(4), e244–e251. https://doi.org/10.3275/8652.

Corstorphine, E. (2006). Cognitive-emotional-behavioural therapy for the eating disorders: Working with beliefs about emotions. European Eating Disorders Review, 14(6), 448–461. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.747.

Courbasson, C. M., Nishikawa, Y., & Shapira, L. B. (2010). Mindfulness-action based cognitive behavioral therapy for concurrent binge eating disorder and substance use disorders. Eating Disorders, 19(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2011.533603.

Cowdrey, F. A., & Park, R. J. (2012). The role of experiential avoidance, rumination and mindfulness in eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 13(2), 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.01.001.

Cowdrey, N. D., & Waller, G. (2015). Are we really delivering evidence-based treatments for eating disorders? How eating-disordered patients describe their experience of cognitive behavioral therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 75, 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.10.009.

Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., Petticrew, M., & Medical Research Council Guidance. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 337, a1655. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.A1655.

Dar, K. A., & Iqbal, N. (2015). Worry and rumination in generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder. The Journal of Psychology, 149(8), 866–880. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2014.986430.

Duarte, J., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2017). Mindfulness, self-compassion and psychological inflexibility mediate the effects of a mindfulness-based intervention in a sample of oncology nurses. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 6(2), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCBS.2017.03.002.

Duarte, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Stubbs, R. J. (2017). Compassionate attention and regulation of eating behaviour: A pilot study of a brief low-intensity intervention for binge eating. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(6), O1437–O1447. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2094.

Ehring, T., & Watkins, E. R. (2008). Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1(3), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2008.1.3.192.

Espel, H. M., Goldstein, S. P., Manasse, S. M., & Juarascio, A. S. (2016). Experiential acceptance, motivation for recovery, and treatment outcome in eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders, 21(2), 205–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0235-7.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(5), 509–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., Doll, H. A., O’Connor, M. E., Bohn, K., Hawker, D. M., Wales, J. A., & Palmer, R. L. (2009). Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with eating disorders: A two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(3), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.0804060.

Fairburn, C. G., Bailey-Straebler, S., Basden, S., Doll, H. A., Jones, R., Murphy, R., O'Connor, M. E., & Cooper, Z. (2015). A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behavior therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders. Behavior Research and Therapy, 70, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.04.010.

Fassino, S., & Abbate-Daga, G. (2013). Resistance to treatment in eating disorders: A critical challenge. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 282. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-282.

Fassino, S., Pierò, A., Tomba, E., & Abbate-Daga, G. (2009). Factors associated with dropout from treatment for eating disorders: A comprehensive literature review. BMC Psychiatry, 9(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-9-67.

Ferreira, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, C. (2013). Self-compassion in the face of shame and body image dissatisfaction: Implications for eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 14(2), 207–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.005.

Fischer, D., Messner, M., & Pollatos, O. (2017). Improvement of interoceptive processes after an 8-week body scan intervention. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 452. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00452.

Fissler, M., Winnebeck, E., Schroeter, T., Gummersbach, M., Huntenburg, J. M., Gaertner, M., & Barnhofer, T. (2016). An investigation of the effects of brief mindfulness training on self-reported interoceptive awareness, the ability to decenter, and their role in the reduction of depressive symptoms. Mindfulness, 7(5), 1170–1181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0559-z.

Fresnics, A. A., Wang, S. B., & Borders, A. (2019). The unique associations between self-compassion and eating disorder psychopathology and the mediating role of rumination. Psychiatry Research, 274, 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2019.02.019.

Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G., & Tavolacci, M. P. (2019). Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5), 1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy342.

Garland, E. L., Hanley, A. W., Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J. (2017). Testing the mindfulness-to-meaning theory: Evidence for mindful positive emotion regulation from a reanalysis of longitudinal data. PLoS One, 12(12), e0187727. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187727.

Germer, C. K., Siegel, R. D., & Fulton, P. R. (Eds.). (2005). Mindfulness and psychotherapy. Guilford Press.

Godfrey, K. M., Gallo, L. C., & Afari, N. (2015). Mindfulness-based interventions for binge eating: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-014-9610-5.

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Wampold, B. E., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011.

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2019). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the treatment of current depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(6), 445–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2018.1556330.

Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J. (2010). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion, 10(1), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018441.

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94.

Gratz, K. L., & Tull, M. T. (2010). Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments. In R. A. Baer (Ed.), Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change (pp. 107–133). Context Press/New Harbinger Publications.

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Bond, R., & Cavanagh, K. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2015.01.006.

Gu, J., Cavanagh, K., & Strauss, C. (2017). Investigating the specific effects of an online mindfulness-based self-help intervention on stress and underlying mechanisms. Mindfulness, 9(4), 1245–1257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0867-y.

Guendelman, S., Medeiros, S., & Rampes, H. (2017). Mindfulness and emotion regulation: Insights from neurobiological, psychological, and clinical studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00220.

Hargus, E., Crane, C., Barnhofer, T., & Williams, J. M. G. (2010). Effects of mindfulness on meta-awareness and specificity of describing prodromal symptoms in suicidal depression. Emotion, 10(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016825.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BRAT.2005.06.006.

Haynos, A. F., Hill, B., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2016). Emotion regulation training to reduce problematic dietary restriction: An experimental analysis. Appetite, 103, 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.04.018.

Hepworth, N. S. (2010). A mindful eating group as an adjunct to individual treatment for eating disorders: A pilot study. Eating Disorders, 19(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2011.533601.

Hoge, E. A., Bui, E., Goetter, E., Robinaugh, D. J., Ojserkis, R. A., Fresco, D. M., & Simon, N. M. (2015). Change in decentering mediates improvement in anxiety in mindfulness-based stress reduction for generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 39(2), 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9646-4.

Holm-Denoma, J. M., & Hankin, B. L. (2010). Perceived physical appearance mediates the rumination and bulimic symptom link in adolescent girls. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39(4), 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2010.486324.

Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671.

Hong, P. Y., Lishner, D. A., & Han, K. H. (2014). Mindfulness and eating: An experiment examining the effect of mindful raisin eating on the enjoyment of sampled food. Mindfulness, 5(1), 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0154-x.

Hudson, J. I., Hiripi, E., Pope, H. G., Kessler, R. C., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 348–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040.

Juarascio, A., Shaw, J., Forman, E., Timko, C. A., Herbert, J., Butryn, M., Bunnell, D., Matteucci, A., & Lowe, M. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy as a novel treatment for eating disorders. Behavior Modification, 37(4), 459–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445513478633.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Delacorte Press.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Random House Publishing Group.

Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432.

Keel, P. K., Dorer, D. J., Franko, D. L., Jackson, S. C., & Herzog, D. B. (2005). Postremission predictors of relapse in women with eating disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(12), 2263–2268. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2263.

Kelly, A. C., & Carter, J. C. (2015). Self-compassion training for binge eating disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 88(3), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12044.

Kelly, A. C., Carter, J. C., & Borairi, S. (2014). Are improvements in shame and self-compassion early in eating disorders treatment associated with better patient outcomes? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22196.

Keng, S. L., Smoski, M. J., Robins, C. J., Ekblad, A. G., & Brantley, J. G. (2012). Mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based stress reduction: Self-compassion and mindfulness as mediators of intervention outcomes. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 26(3), 270–280. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.26.3.270.

Khalsa, S. S., & Lapidus, R. C. (2016). Can interoception improve the pragmatic search for biomarkers in psychiatry? Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7, 121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00121.

Khalsa, S. S., Craske, M. G., Li, W., Vangala, S., Strober, M., & Feusner, J. D. (2015). Altered interoceptive awareness in anorexia nervosa: Effects of meal anticipation, consumption and bodily arousal. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(7), 889–897. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22387.

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., Chapleau, M. A., Paquin, K., & Hofmann, S. G. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 763–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005.

Kiken, L. G., Garland, E. L., Bluth, K., Palsson, O. S., & Gaylord, S. A. (2015). From a state to a trait: Trajectories of state mindfulness in meditation during intervention predict changes in trait mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences, 81, 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.044.

Kissileff, H. R., Wentzlaff, T. H., Guss, J. L., Walsh, B. T., Devlin, M. J., & Thornton, J. C. (1996). A direct measure of satiety disturbance in patients with bulimia nervosa. Physiology & Behavior, 60(4), 1077–1085 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8884936.

Kral, T. R. A., Schuyler, B. S., Mumford, J. A., Rosenkranz, M. A., Lutz, A., & Davidson, R. J. (2018). Impact of short- and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. NeuroImage, 181, 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2018.07.013.

Kristeller, J. L., & Hallett, C. B. (1999). An exploratory study of a meditation-based intervention for binge eating disorder. Journal of Health Psychology, 4(3), 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910539900400305.

Kristeller, J. L., & Wolever, R. Q. (2010). Mindfulness-based eating awareness training for treating binge eating disorder: The conceptual foundation. Eating Disorders, 19(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2011.533605.

Kristeller, J., Wolever, R. Q., & Sheets, V. (2014). Mindfulness-based eating awareness training (MB-EAT) for binge eating: A randomized clinical trial. Mindfulness, 5(3), 282–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0179-1.

Kuyken, W., Watkins, E., Holden, E., White, K., Taylor, R. S., Byford, S., Evans, A., Radford, S., Teasdale, J. D., & Dalgleish, T. (2010). How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(11), 1105–1112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.08.003.

Kuyken, W., Warren, F. C., Taylor, R. S., Whalley, B., Crane, C., Bondolfi, G., Hayes, R., Huijbers, M., Ma, H., Schweizer, S., Segal, Z., Speckens, A., Teasdale, J. D., Van Heeringen, K., Williams, M., Byford, S., Byng, R., & Dalgleish, T. (2016). Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(6), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0076.

Labelle, L. E., Campbell, T. S., & Carlson, L. E. (2010). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in oncology: Evaluating mindfulness and rumination as mediators of change in depressive symptoms. Mindfulness, 1(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-010-0005-6

Labelle, L. E., Campbell, T. S., Faris, P., & Carlson, L. E. (2015). Mediators of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR): Assessing the timing and sequence of change in cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22117.

Lampard, A. M., Byrne, S. M., McLean, N., & Fursland, A. (2011). Avoidance of affect in the eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 12(1), 90–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EATBEH.2010.11.004.

Lattimore, P., Mead, B. R., Irwin, L., Grice, L., Carson, R., & Malinowski, P. (2017). ‘I can’t accept that feeling’: Relationships between interoceptive awareness, mindfulness and eating disorder symptoms in females with, and at-risk of an eating disorder. Psychiatry Research, 247, 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.022.

Lavender, J. M., Wonderlich, S. A., Peterson, C. B., Crosby, R. D., Engel, S. G., Mitchell, J. E., Crow, S. J., Smith, T. L., Klein, M. H., Goldschmidt, A. B., & Berg, K. C. (2014). Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in bulimia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(3), 212–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2288.

Leahey, T. M., Crowther, J. H., & Irwin, S. R. (2008). A cognitive-behavioral mindfulness group therapy intervention for the treatment of binge eating in bariatric surgery patients. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 15(4), 364–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CBPRA.2008.01.004.

Linardon, J., Fairburn, C. G., Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Wilfley, D. E., & Brennan, L. (2017). The empirical status of the third-wave behaviour therapies for the treatment of eating disorders: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 58, 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2017.10.005.

Lowe, M. R. (1993). The effects of dieting on eating behavior: A three-factor model. Psychological Bulletin, 114(1), 100–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.100.

Machado, P. P. P., Machado, B. C., Gonçalves, S., & Hoek, H. W. (2007). The prevalence of eating disorders not otherwise specified. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(3), 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20358.

Mallorquí-Bagué, N., Vintró-Alcaraz, C., Sánchez, I., Riesco, N., Agüera, Z., Granero, R., Jiménez-Múrcia, S., Menchón, J. M., Treasure, J., & Fernández-Aranda, F. (2018). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic feature among eating disorders: Cross-sectional and longitudinal approach. European Eating Disorders Review, 26(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2570.

Masuda, A., & Latzman, R. D. (2012). Psychological flexibility and self-concealment as predictors of disordered eating symptoms. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 1(1–2), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2012.09.002.

Mendes, A. L., Ferreira, C., & Marta-Simões, J. (2017). Experiential avoidance versus decentering abilities: The role of different emotional processes on disordered eating. Eating and Weight Disorders, 22(3), 467–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0291-7.

Merwin, R. M. (2011). Anorexia nervosa as a disorder of emotion regulation: Theory, evidence, and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18(3), 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01252.x.

Michie, S., & Prestwich, A. (2010). Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychology, 29(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016939.

Naumann, E., Tuschen-Caffier, B., Voderholzer, U., Caffier, D., & Svaldi, J. (2015). Rumination but not distraction increases eating-related symptoms in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(2), 412–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000046.

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843X.109.3.504.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Stice, E., Wade, E., & Bohon, C. (2007). Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(1), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x.

Norton, A. R., Abbott, M. J., Norberg, M. M., & Hunt, C. (2015). A systematic review of mindfulness and acceptance-based treatments for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(4), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22144.

Nowakowski, M. E., McFarlane, T., & Cassin, S. (2013). Alexithymia and eating disorders: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Eating Disorders, 1(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-2974-1-21.

Palmeira, L., Trindade, I. A., & Ferreira, C. (2014). Can the impact of body dissatisfaction on disordered eating be weakened by one’s decentering abilities? Eating Behaviors, 15(3), 392–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.04.012.

Pinto-Gouveia, J., Carvalho, S. A., Palmeira, L., Castilho, P., Duarte, C., Ferreira, C., Duarte, J., Cunha, M., Matos, M., & Costa, J. (2016). Incorporating psychoeducation, mindfulness and self-compassion in a new programme for binge eating (BEfree): Exploring processes of change. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(4), 466–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316676628.

Pisetsky, E. M., Haynos, A. F., Lavender, J. M., Crow, S. J., & Peterson, C. B. (2017). Associations between emotion regulation difficulties, eating disorder symptoms, non-suicidal self-injury, and suicide attempts in a heterogeneous eating disorder sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 73, 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.11.012.

Rawal, A., Park, R. J., & Williams, J. M. G. (2010). Rumination, experiential avoidance, and dysfunctional thinking in eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(9), 851–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BRAT.2010.05.009.

Roemer, L., Williston, S. K., & Rollins, L. G. (2015). Mindfulness and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COPSYC.2015.02.006.

Safer, D. L., Telch, C. F., & Agras, W. S. (2001). Dialectical behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(4), 632–634. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.632.

Safran, J. D., & Segal, Z. V. (1990). Interpersonal process in cognitive therapy. Jason Aronson.

Sala, M., & Levinson, C. A. (2016). The longitudinal relationship between worry and disordered eating: Is worry a precursor or consequence of disordered eating? Eating Behaviors, 23, 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.07.012.

Sala, M., & Levinson, C. A. (2017). A longitudinal study on the association between facets of mindfulness and disinhibited eating. Mindfulness, 8(4), 893–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0663-0.

Sala, M., Brosof, L. C., & Levinson, C. A. (2019a). Repetitive negative thinking predicts eating disorder behaviors: A pilot ecological momentary assessment study in a treatment seeking eating disorder sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 112, 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BRAT.2018.11.005.