Abstract

In modern western societies, the female body is a predominantly used dimension in self and social evaluations. In fact, the perceived discrepancy between one’s current and ideal body image may act as a pathogenic phenomenon on women’s well-being. Furthermore, significant differences in the tendency to engage in disordered eating attitudes and behaviours have been verified between women sharing similar characteristics and perceptions about body's weight and shape, which suggests that different emotion regulation processes may be involved in this association. This study thus aims to clarify the mediational effect of two different emotional regulation processes, experiential avoidance and decentering, on the association of weight and body shape-related variables and shame with disordered eating, in a sample of 760 women. The tested path model explained 44 % of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours, and showed an excellent model fit. Results demonstrated that body mass index had a direct effect, albeit weak, on disordered eating behaviours, and that body-image discrepancy and shame presented indirect effects through the mechanisms of experiential avoidance and decentering. Results also revealed that experiential avoidance and decentering showed significant mediator effects on the relationship of weight and body shape and shame with disordered eating behaviours. These findings suggested that while experiential avoidance exacerbates the impact of weight and body shape and shame on disordered eating attitudes and behaviours, decentering seems to attenuate this association. Our findings appear to offer significant clinical and research implications, highlighting the importance of targeting maladaptive emotion processes and of the development of decentering abilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Women’s perceived discrepancies between current and idealized body image have been pointed out as a central risk factor for eating psychopathology (e.g., [1]).In fact, several accounts suggested that these perceived discrepancies may explain body-image dissatisfaction and promote maladaptive eating-related behaviours (e.g., [2, 3]). Moreover, the perception of one’s own body as different from the socially idealized body is associated with negative affect, such as shame (e.g., [4, 5]).

In accordance with the biopsychosocial model, shame is a self-conscious emotion which emerges in the relational context when one perceives that the self exists negatively in the mind of others [as inferior, undesirable, or powerless (e.g., [6, 7])]. Indeed, this painful affect arises as a warning sign that allows to notice one’s characteristics and/or behaviours as incapable of positively impress others, putting the self at risk of criticism and rejection (e.g., [7, 8]). In this sense, shame is fundamentally a socially focused emotion of great evolutionary significance linked to a series of defense responses (e.g., concealment or submission [8]). Particularly, literature has suggested that some individuals, when dealing with shame experiences, may endorse maladaptive defensive strategies with the purpose of correcting or concealing one’s negatively perceived attributes or characteristics (e.g., [9, 10]). In fact, although shame has been highlighted as an adaptive emotion, high levels of shame are strongly associated with several social difficulties, and to different mental health conditions (e.g., [8, 11]). Furthermore, literature suggested shame as a central feature in body-image and eating difficulties (e.g., [12, 13]).

In modern societies, the female body shape is a particularly used dimension in self and social evaluations (e.g., [14, 15]). This context may explain shame feelings in women who perceive their body as significantly different from female attractiveness’ sociocultural standards. Moreover, negative feelings (e.g., inferiority) may explain women’s engagement in maladaptive behaviours (e.g., [16, 17]). In this line, disordered eating behaviours may arise with the intention of controlling weight and body shape and serve the functional purpose of avoiding being rejected or judged due to one’s body image [12, 13]. However, differences in eating psychopathology between women that shared similar weight and shape perceptions have been reported, which suggests that different emotional regulation processes may be involved in this association.

In accordance with Hayes, Strosahl, and Wilson [18], human suffering mainly emerges from attempts to avoid or control adverse inner events (e.g., emotions, sensations, and thoughts; [19]). For that reason, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy's (ACT) interventions aim to increase psychological flexibility by developing one´s availability to experience and accept internal experiences [20].

Experiential avoidance is a main process of psychological inflexibility conceptualized as the unwillingness to be in contact with certain particular inner experiences (e.g., emotions, thoughts, or bodily sensations) and the effort to avoid or control the frequency, form, and context in which they occur (e.g., [18, 21]). This process is not by itself malignant, since its evolutionary adaptive function; however, it can associate with several psychopathological processes (e.g., rumination, maladaptive perfectionism, and cognitive suppression [22–24]) and become a disordered process, by serving the purpose of inflexibly and rigidly controlling unwanted internal events [25]. Research has shed light on the role of different psychological inflexibility processes in the proneness of some individuals to eating disorders (e.g., [26]), namely experiential avoidance, manifested by extreme diet, binge eating, or compensatory behaviours [27, 28].

In contrast, and in line with the promotion of psychological flexibility, decentering is an important mechanism against psychopathological symptomatology and a fundamental therapeutic process of change (e.g., [18, 29]). In fact, this process is conceptualized as the capability of observing and coping with one’s inner experiences (thoughts or feelings) as subjective and temporary events which occur in the mind, as opposed to objective reflections of the self or reality [30, 31]. Decentering abilities, contrarily to self-focused forms of attention, allow individuals to observe one’s feelings and thoughts and to recognize them as mere products of the mind that do not demand particular responses [30]. Furthermore, decentering has been described as the ability to adopt a present-focused, nonjudging, and accepting attitude towards one’s own private events [32]. Research has pointed out the positive association between the adoption of a decentered perspective and well-being [30, 33].

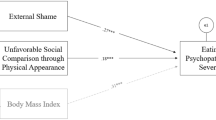

The present study examines a path model which explores the role of experiential avoidance and decentering in the relationship between core risk factors of eating psychopathology and the engagement in maladaptive eating behaviours. Specifically, this model explored the mediational role of these different emotional processes in the link between body mass index (BMI), body-image discrepancy, and external shame and disordered eating behaviours. It is hypothesized that experiential avoidance may fuel the association between body-image variables and external shame and eating psychopathology’s variance. In turn, it is expected that decentering abilities attenuate these association.

Materials and methods

Procedures

The current investigation is part of a wider research project about the impact of emotion regulation processes in quality of life and eating psychopathology, in the Portuguese population.

This study respected all ethical and deontological issues inherent to scientific research. Self-report measures were administered by the authors after the Ethics Committees and boards of the institutions involved (e.g., colleges, private companies, and retail services) approved the research. All participants gave their written informed consent after being informed about the purpose and procedures of the study, the voluntary nature of their cooperation, and the confidentiality of the data.

The original sample consisted of 1099 participants of both genders, aged between 17 and 60 years. However, considering the aims of this study, data were cleaned to exclude: (1) male participants and (2) participants who were younger than 18 or older than 35 years. The final sample was composed of 760 women.

Participants

A total of 760 women from the general population (including students and individuals working in private companies and retail services), with ages ranging from 18 to 35, participated in this study. Participants presented a mean age of 20.66 (SD = 2.18) and a mean of 13.23 (SD = 1.61) years of education.

Participants' body mass index (BMI) mean was 21.86 (SD = 3.13), corresponding to normal weight values [34]. Moreover, it was verified that the sample’s BMI distribution is equivalent to the female Portuguese population’s BMI distribution [35].

Measures

Body mass index (BMI) BMI, a measure of body fat, was calculated from participants' self-reported current height and weight using the Quetelet Index (Kg/m2).

Figure rating scale (FRS; [ 36, 37 ]) FRS is a well-known measure of body image with good psychometric properties [36]. It consists of a series of nine schematic figures of different sizes, ranging from a very thin silhouette (1) to a very large silhouette (9). Participants were asked to select two silhouettes, one that best indicate their self-perceived current body shape and other that represents their ideal body image. FRS was, therefore, used as a measure of the discrepancy between the actual and the ideal body image(BID), by calculating the difference between the two chosen silhouettes.

Other as shamer scale-2 (OAS-2; [ 38 ]). This is a shorter version of the OAS [39] consisting of eight items to evaluate external shame, that is, the perception that others judge the self negatively (e.g., “I think that other people look down on me”). The response options are rated on a five-point scale, ranging from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“almost always”). Higher results in this scale indicate higher levels of external shame [39]. OAS-2 has shown excellent internal consistency (0.82); concerning the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

Experiences Questionnaire (EQ; [ 30, 40 ]). The EQ comprises 20 items that aim to assess the participants' abilities of decentration and disidentification with negative thoughts in daily experiences (e.g., “I can observe unpleasant feelings without being drawn into them”). These items are scored on a five-point scale (ranging from 1: Never to 5: Always), according to their frequency, with higher scores indicating greater capability to view one’s feelings and thoughts as temporary and separated from the self. This scale has shown good reliabilities in the original version (α = 0.83) and in the Portuguese version (α = 0.81). In this study, its Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79.

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II; [ 41, 42 ]). The AAQ-II is a 7-item scale which assesses experiential avoidance (e.g., ‘I worry about not being able to control my worries and feelings’). Participants evaluate each item on a seven-point scale (ranging from 0: Never true, to 7: Always true) according to their accuracy. This measure revealed good internal consistency values in the original study (α = .84, across six samples) and in the Portuguese validation study (α = 0.90). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q; [ 43, 44 ]) The EDE-Q is a 36-item self-report questionnaire adapted from the Eating Disorder Examination Interview (EDE; [45]). It consists of four subscales (restraint, weight concern, shape concern, and eating concern) which evaluate the frequency and intensity of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours. The items are rated for the frequency of occurrence or for the severity. Higher scores reveal greater levels of disturbance. This measure presented good psychometric properties in both the original and the Portuguese versions. In the current study, the global and subscale’s score of EDE-Q presented a Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.74 to 0.93.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the software IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 (v.22; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and path analysis was performed via the software AMOS [46].

Descriptive statistics were performed (means and standard deviations) to analyze the characteristics of the final sample. Product-moment Pearson correlation analyses were performed [47] to examine the relationships between the study’s variables. Finally, path analyses were conducted to explore whether BMI, body-image discrepancy (BID), and external shame (OAS-2) would predict disordered eating attitudes and behaviours (global score of EDE-Q), mediated by decentering (EQ) and experiential avoidance (AAQ-II). BMI, body-image discrepancy, and external shame were considered as exogenous variables; decentering and experiential avoidance were hypothesized as mediator variables, and EDE-Q was the dependent endogenous variable. The maximum-likehood method was used to estimate the significance of all model's path coefficients and fit statistics, and a series of goodness-of-fit measures were calculated to examine the adequacy of the overall model (e.g., CMIN/DF; CFI; TLI; RMSEA; [48]). The adjustment of the path model to the empirical data was analyzed recurring to the Chi-square goodness-of-fit (that indicates a good fit when non-significant; [49]), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker and Lewis Index (TLI) which reveal a good model fit when values are superior to .95 [48, 50], and the Root-Mean-Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA, which reveals a good adjustment when values are inferior to .06; [48]). Resorting to the Bootstrap resampling method, the significance of the direct, indirect, and total effects was also examined, with 5000 Bootstrap samples, and 95 % bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) around the standardized estimates of total, direct, and indirect effects. The fit of individual parameters in the model was assessed through the analysis of parameters estimates (b, which indicates that the model is poor when their signal falls outside the admissible signal range; [51]) and standard errors (SE, another indicator of poor model fit when excessively large or small; [51]). The indirect effects were considered statistically different from zero (p < 0.05) if zero was not on the interval between the lower and the upper bound of the 95 % bias-corrected confidence interval [52].

Results

Preliminary analyses

Univariate and multivariate normalities were confirmed by the analysis of Skewness (Sk) and Kurtosis (Ku) values [52]. In addition, preliminary analyses showed that data followed the assumptions of normality, homoscedasticity, linearity, independence of errors, and multicollinearity among the variables [53].

Descriptive and correlations analyses

Descriptive and Pearson’s correlation results are presented in Table 1.

Results showed that BMI was positively and strongly associated with body-image discrepancy (BID) and moderately with eating psychopathology (EDE-Q). In addition, results demonstrated that BMI revealed a non-significant association with external shame (OAS-2), decentering abilities (EQ), and experiential avoidance (AAQ-II). Furthermore, results indicated that BID presented weak correlations with OAS-2 and EQ, positive and negative, respectively, and a non-significant association with AAQ-II. In addition, BID showed a positive and strong correlation with EDE-Q.

OAS-2 presented significant associations with the studied emotional processes, a negative and moderate correlation with EQ, and a positive and strong association with AAQ-II. Furthermore, OAS-2 showed a positive and moderate association with the global measure of eating psychopathology (EDE-Q). EQ and AAQ-II revealed a negative and strong association between each other and were moderately associated with EDE-Q (with negative and positive correlations, respectively). Finally, regarding the EDE-Q’s subscales, positive associations, from weak to moderate magnitudes, were found with BMI. With BDI, OAS-2, and AAQ, the EDE-Q’s subscales correlated positively, with moderate-to-high correlations (except for the weak correlation between EDE-Q_rest and OAS). In addition, negative correlations were found between EDE-Q’s subscales and EQ.

Path analysis

Path analysis was performed to test whether decentering and experiential avoidance mediate the effects of BMI, body-image discrepancy, and external shame on the engagement in disordered eating behaviours.

The theoretical model was tested by a saturated model (i.e., with zero degrees of freedom), comprising 24 parameters. Results indicated that three paths were not significant: the direct effect of body-image discrepancy on experiential avoidance (b BD = .425; SE b = .325; Z = 1.31; p = .191); the direct effect of BMI on decentering (b BMI = .089; SE b = .065; Z = 1.58; p = .169); and the direct effect of BMI on experiential avoidance (b BMI = −.124; SE b = .078; Z = −1.59; p = .112). These paths were progressively removed and the rectified model was then tested.

The final model (Fig. 1) presented an excellent model fit, with a non-significant Chi-Square [\(X_{{_{( 3)} }}^{ 2}\) = 6.127; p = .106] and excellent goodness-of-fit indices (CMIN/DF = 2.042; CFI = .998; TLI = .988; RMSEA = .037; [IC = .000 − .079; p = .631]; [53]. All path coefficients were statistically significant (p < .05) and in the expected directions. The model explained 44 % of EDE-Q's variance and accounted for 16 % and 28 % of decentering and experiential avoidance's variances, respectively.

Body-image discrepancy predicted decentering and EDE-Q variance, with a direct effect of −.07 (b BD = −.350; SE b = .162; Z = −2.168; p = .030) and .44 (b BD = .488; SE b = .038; Z = 12.877; p < .001), respectively. BMI directly predicted higher levels of EDE-Q, with an effect of .09 (b BMI = .033; SE b = .012; Z = 2.810; p = .005). In turn, external shame had a direct effect of −.38 on decentering (b OAS = −.384; SE b = .034; Z = −11.454; p < .001), of .53 on experiential avoidance (b OAS = .868; SE b = .051; Z = 17.170; p < .001), and of .10 on EDE-Q (b OAS = .022; SE b = .007; Z = 3.194; p < .010). It was also verified that both decentering and experiential avoidance had a direct effect of −.13 (b EQ = −.027; SE b = .007; Z = −3.972; p < .001) and .24 (b AAQ = .031; SE b = .005; Z = 6.772; p < .001) on EDE-Q, respectively.

The analysis of indirect effects revealed that body-image discrepancy presented an indirect effect of .01 on EDE-Q through the mechanisms of decentering (95 % CI = .000–.019). External shame presented an indirect effect of .17 (95 % CI = .14–.22) on EDE-Q, which was partially mediated through the mechanisms of decentering and experiential avoidance, respectively.

Overall, the model accounted for 44 % of eating psychopathology’s variance, and revealed that decentering abilities and the tendency to engage in experiential avoidance mediate the impact of body-image discrepancy and external shame on disordered eating behaviours.

Discussion

Consistent empirical evidence has been suggesting that the perceived discrepancy between one’s current weight and body shape and an ideal body image is a pathogenic phenomenon for women’s well-being and mental health (e.g., [2]). Several studies have suggested that the pervasive effect of this discrepancy may be explained by shame feelings and by the engagement in disordered eating attitudes and behaviours (e.g., [9]). Nevertheless, research has pointed out significant differences in the tendency to adopt disordered eating behaviours between women that shared similar weight and body shape characteristics and perceptions, which suggests that different emotional regulation processes may be involved in this association.

The current study aimed to further explore how experiential avoidance and decentering abilities mediate the impact of core risk factors of eating psychopathology (BMI, body-image discrepancy and external shame) on the engagement in disordered eating behaviours.

Our results seem to corroborate literature (e.g., [2, 3]) and are in accordance with our hypothesis, indicating that BMI, body-image discrepancy, and external shame are linked to higher levels of disordered eating behaviours. Furthermore, these findings confirm previous research (e.g., [28, 33]) revealing the moderate association of decentering abilities and experiential avoidance on EDE-Q (with negative and positive correlations, respectively).

These associations were further examined through a path analysis that tested the impact of BMI, body-image discrepancy, and external shame on EDE-Q, considering the mediator effects of experiential avoidance and decentering abilities. Results showed that the tested model explained a total of 44 % of eating psychopathology’s variance and presented an excellent model fit. Moreover, results indicated that women who presented higher body-image discrepancy, defined as the difference between one’s perceived current body shape and ideal body image [37], and showed higher levels of shame revealed a greater tendency to engage in disordered eating attitudes. In addition, BMI revealed a significant, albeit weak, direct impact on eating psychopathology. It is also noteworthy that the impact of body-image discrepancy and external shame on disordered eating behaviours were partially mediated by experiential avoidance and decentering abilities. These findings indicate that even higher discrepancy between one’s current and idealized body image and shame directly impact on the adoption of maladaptive eating behaviours, the attempt to control, or avoid inner experiences significantly amplifies these associations. In contrast, decentering (that is, the ability to adopt a present-focused, nonjudging, and accepting attitude towards one’s own thoughts and feelings [32]) seems to attenuate the impact of the negative perception of body image and shame on disordered eating. Our results seem to suggest that decentering abilities and experiential avoidance are important mechanisms to explain the impact of body-image negative perceptions and a sense of inferiority or undesirability on the engagement in disordered eating behaviours. In fact, the current study suggests that the impact of body-image discrepancy and external shame in the proneness to eating psychopathology is mediated through lower levels of decentering and higher levels of experiential avoidance.

However, the present results should be considered along with several limitations. First, the main limitation of this study concerns its cross-sectional nature, which does not allow the inference of casual directions between the studied variables. To determine the directionally of the relations, a longitudinal research should be conducted. Another limitation is the use of a sample exclusively composed of women from the general population. Even though the engagement in disordered eating behaviours is more prevalent in females, upcoming studies should explore this model in male samples and investigate gender differences. Future research should also analyze our hypothesis in clinical populations (e.g., obese and eating disorder patients). Finally, another possible limitation is related to the use of self-report measures, which may be susceptible to biases and impair the generalization of the data. Future research should use other non-self-report instruments (such as structured interviews) to test our findings.

In conclusion, our results seem to support the hypothesis that the impact of body-image discrepancy and of external shame on disordered eating behaviours is carried by the effect of lower decentering abilities and higher experiential avoidance. Furthermore, our findings seem to hold relevant contributions for the development of intervention programs in the community to target body and eating difficulties, emphasizing the importance of the development of decentering and acceptance abilities.

References

Blowers LC, Loxton NJ, Grady-Flesser M, Occhipinti S, Dawe S (2003) The relationship between sociocultural pressure to be thin and body dissatisfaction in preadolescent girls. Eat Behav 4(3):229–244. doi:10.1016/S14710153(03)00018-7

Mond J, Mitchison D, Latner J, Hay P, Owen C, Rodgers B (2013) Quality of life impairment associated with body dissatisfaction in a general population sample of women. BMC Public Health. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-920

Stice E, Shaw HE (2002) Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: a synthesis of research findings. J Psychosom Res 53(5):985–993. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9

Furnham A, Badmin N, Sneade I (2002) Body image dissatisfaction: gender differences in eating attitudes, self-esteem, and reasons for exercise. J Psychol 136(6):581–596. doi:10.1080/00223980209604820

Gilliard TS, Lackland DT, Mountford WK, Egan BM (2007) Concordance between self-reported heights and weights and current and ideal body images in young adult African American men and women. Ethn Dis 17(4):617–623

Gilbert P (2007) The evolution of shame as a marker for relationship security: a biopsychosocial approach. In: Tracy J, Robin R, Tangney J (eds) The self-conscious emotions: theory and research. Guilford, New York, pp 283–309

Tangney JP, Dearing RL (2002) Shame and guilt. Guilford Press, New York

Gilbert P (2002) Body shame: A biopsychosocial conceptualization and overview with treatment implications. In: Gilbert P, Miles J (eds) Body shame: conceptualisation, research and treatment. Brunner Routledge, New York, pp 3–54

Ferreira C, Trindade IA, Ornelas L (2015) Exploring drive for thinness as a perfectionistic strategy to escape from shame experiences. Span J Psychol. doi:10.1017/sjp.2015.27

Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Sherry SB, Habke M, Parkin M, Lam RW, McMurtry B, Ediger E, Stein M, Fairlie P (2003) The interpersonal expression of perfectionism: perfectionistic self-presentation and psychological distress. J Pers Soc Psychol 84(6):1303–1325. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1303

Lamont JM (2015) Trait body shame predicts health outcomes in college women: a longitudinal investigation. J Behav Med. doi:10.1007/s10865-015-9659-9

Goss KP, Gilbert P (2002) Eating disorders, shame and pride: a cognitive-behavioural functional analysis. In: Gilbert P, Miles J (eds) Body shame: conceptualization, research and treatment. Brunner-Routledge, Hove, pp 219–255

Pinto-Gouveia J, Ferreira C, Duarte C (2014) Thinness in the pursuit for social safeness: an integrative model of social rank mentality to explain eating psychopathology. Clin Psychol Psychother 21(2):154–165. doi:10.1002/cpp.1820

Troop NA, Allan S, Treasure JL, Katzman M (2003) Social comparison and submissive behaviour in eating disorders. Psychol Psychother: Theory, Res Pract 76:237–249. doi:10.1348/147608303322362479

Ferreira C, Pinto-Gouveia J, Duarte C (2013) Drive for thinness as a women´s strategy to avoid inferiority. Int J Psychol Psychol Ther 13(1):15–29

Cockell SJ, Hewitt PL, Seal B, Sherry S, Goldner EM, Flett GL, Remick RA (2002) Trait and self-presentational dimensions of perfectionism among women with anorexia nervosa. Cogn Ther Res 26(6):745–758. doi:10.1023/A:102123741636

Strahan EJ, Wilson AE, Cressman KE, Buote VM (2006) Comparing to perfection: how cultural norms for appearance affect social comparisons and self-image. Body Image 3:211–227. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.07.004

Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG (1999) Acceptance and commitment therapy: an experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press, New York

Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG (2012) Acceptance and commitment therapy: the process and practice of mindful change, 2nd edn. Routledge, London

Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond F, Masuda A, Lillis J (2006) Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther 44:1–25. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

Hayes SC, Gifford EV (1997) The trouble with language: experiential avoidance, rules and the nature of verbal events. Psychol Sci 8:170–173

Campbell-Sills L, Barlow DH, Brown TA, Hofmann SG (2006) Effects of suppression and acceptance on emotional responses on individuals with anxiety and mood disorders. Behav Res Ther 23:1037–1046. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.001

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Harrel ZA (2002) Rumination, depression, and alcohol use: tests of gender differences. J Cognit Psychother: Int Quart 16:391–403. doi:10.1891/jcop.16.4.391.52526

Santanello AW, Gardner FL (2007) The role of experiential avoidance in the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and worry. Cogn Ther Res 31:319–332. doi:10.1007/s10608-006-9000-6

Kashdan TB, Barrios V, Forsyth JP, Steger MF (2006) Experiential avoidance as a generalized psychological vulnerability: comparisons with coping and emotion regulation strategies. Behav Res Ther 9:1301–1320. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.003

Heffner M, Eifert GH (2004) The anorexia workbook: how to accept yourself, heal your suffering, and reclaim your life. New Harbinger Publications, Oakland

Claes L, Vandereycken W, Vertommen H (2001) Self-injurious behaviours in eating-disordered patients. Eat Behav 2:263–272

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R (2003) Cognitive-behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther 41:509–528. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8

Sauer S, Baer RA (2010) Mindfulness and decentering as mechanisms of change in mindfulness and acceptance-based interventions. In: Baer RA (ed) Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change. New Harbinger, Oakland, pp 25–50

Fresco DM, Moore MT, Dulmen MH, Segal ZV, Ma SH, Teasdale JD et al (2007) Initial psychometric properties of the experiences questionnaire: validation of a self-report measure of decentering. Behav Ther 38:234–246

Safran JD, Segal ZV (1990) Interpersonal process in cognitive therapy. Basic Books, New York

Fresco DM, Segal ZV, Buis T, Kennedy S (2007) Relationship of posttreatment decentering and cognitive reactivity to relapse in major depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 75(3):447–455. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.447

Lara P, Trindade IA, Ferreira C (2014) Can the impact of body dissatisfaction on disordered eating be weakened by one’s decentering abilities? Eat Behav 5(3):392–396. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.04.012

WHO (1995) Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Reports of a WHO Expert Committee. WHO Technical Report series 854. Geneva, World Health Organization

Poínhos R, Franchini B, Afonso C, Correia F, Teixeira VH, Moreira P, Durão C, Pinho O, Silva D, Lima Reis JP, Veríssimo T, de Almeida MDV (2009) Alimentação e estilos de vida da população Portuguesa: metodologia e resultados preliminares [Alimentation and life styles of the Portuguese population: methodology and preliminary results]. Alimentação Humana 15(3):43–60

Thompson JK, Altabe MN (1991) Psychometric qualities of the figure rating scale. Int J Eat Disord 10(5):615–619. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199109)10:5<615:AID-EAT2260100514>3.0.CO;2-K

Ferreira C (2003) Anorexia Nervosa: A expressão visível do invisível. Contributos para a avaliação de atitudes e comportamentos em relação ao peso e à imagem corporal [Anorexia Nervosa: The visible expression of the invisible. Contributions for the assessment of attitudes and behaviors in relation to weight and body image]. (Unpublished master´s thesis). University of Coimbra, Coimbra

Matos M, Pinto-Gouveia J, Gilbert P, Duarte C, Figueiredo C (2015) The other as shamer scale—2: development and validation of a short version of a measure of external shame. Personal Individ Differ 74:6–11. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.037

Goss K, Gilbert P, Allan S (1994) An exploration of shame measures: I: the ‘other as shamer’scale. Personal Individ Differ 17(5):713–717. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90149-X

Pinto-Gouveia J, Gregório S, Duarte C, Simões L (2012) Decentering: psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the experiences questionnaire (EQ). In: Quevedo-Blasco R, Quevedo-Blasco V (eds) Avances en psicología clínica, pp 445–449. Santander: Asociación Española de Psicología Conductual (AEPC). http://www.ispcs.es/xcongreso/portugues/livroresumos.html

Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KC, Guenole N, Orcutt HK, Waltz T, Zettle RD (2011) Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological flexibility and acceptance. Behav Ther 42:676–688. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007

Pinto-Gouveia J, Gregório S, Dinis A, Xavier A (2012) Experiential avoidance in clinical and non-clinical samples. Int J Psychol Psychol Ther 12:139–156

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (1994) Assessment of eating disorders: interview of self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 16(4):363–370. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199412)

Machado PP, Martins C, Vaz AR, Conceição E, Bastos AP, Gonçalves S (2014) Eating disorder Examination questionnaire: psychometric properties and norms for the Portuguese population. Eur Eat Disord Rev 22(6):448–453. doi:10.1002/erv.2318

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z (1993) The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT (eds) Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment, 12th edn. Guilford, New York, pp 317–360

Arbuckle JL (2006) Amos (Version 7.0) [Computer Program]. Chicago: SPSS

Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS (2003) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences, 3rd edn. Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Hu L, Bentler P (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55

Hair J, Anderson R, Tatham R, Black W (1998) Multivariate data analysis, 5th edn. Prentice Hall International, London

Hopper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M (2008) Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron J Bus Res Methods 6(1):53–60

Byrne BM (2010) Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming, 2nd edn. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ

Kline RB (2005) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 2nd edn. Guilford Press, New York

Field A (2004) Discovering statistics using SPSS, 3rd edn. Sage Publications, London

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mendes, A.L., Ferreira, C. & Marta-Simões, J. Experiential avoidance versus decentering abilities: the role of different emotional processes on disordered eating. Eat Weight Disord 22, 467–474 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0291-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0291-7