Abstract

Lead ions (Pb2+) possess characteristics similar to Ca2+. Because of this and its redox capabilities, lead causes different toxic effects. The neurotoxic effects have been well documented; however, the toxic effects on cardiac tissues remain allusive. We utilized isolated guinea pig hearts and measured the effects of Pb2+ on their contractility and excitability. Acute exposure to extracellular Pb2+ had a negative inotropic effect and increased diastolic tension. The speed of contraction and relaxation were affected, though the effects were more dramatic on the speed of contraction. Excitability was also altered. Heart beat frequency increased and later diminished after lead ion exposure. Pro-arrhytmic events, such as early after-depolarization and a reduction of the action potential plateau, were also observed. In isolated cardiomyocytes and tsA 201 cells, extracellular lead blocked currents through Cav1.2 channels, diminished their activation, and enhanced their fast inactivation, negatively affecting their gating currents. Thus, Pb2+ was cardiotoxic and reduced cardiac contractility, making the heart prone to arrhythmias. This was due, in part, to Pb2+ effects on the Cav1.2 channels; however, other channels, transporters or pathways may also be involved. Acute cardiotoxic effects were observed at Pb2+ concentrations achievable during acute lead poisoning. The results suggest how Cav1.2 gating can be affected by divalent cations, such as Pb2, and also suggest a more thorough evaluation of heart function in individuals affected by lead poisoning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lead is a post-transition heavy metal whose usual ionic form is +2 (Pb2+) (Casas and Sordo 2011). It is basically a non-biodegradable, toxic material that is found naturally and has widespread human uses, but can also cause significant environmental contamination. Human exposure to organic or inorganic lead can result in acute or chronic poisoning. Thus, it is a relevant worldwide health problem (Gidlow 2015). Though lead intoxication in humans has diminished since the prohibition of lead addition to gasoline and paint, it is still a problem for certain populations at risk of exposure related to the manufacturing and disposal of some car batteries and other commercial products. It has been estimated by the WHO Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation that nearly 1 million people died worldwide in 2013 because of lead poisoning (Organization 2016).

Lead has been in use by humans for different purposes since approximately 4000 BC. It began to be recognized as toxic around 200 BC, but its toxicity was clearly identified after the seminal work by Burton and Turner in the nineteenth century (Pearce 2007). Since then, lead toxicity began to be recognized and characterized in children and adults (Chandran and Cataldo 2010). Chronic exposure to lead has effects on the nervous system, mainly during its development. It produces neurocognitive, behavioral and psychiatric problems. It also impairs renal and reproductive functions, causes anemia, diminishes vitamin D levels and increases the risk for hypertension (Rosin 2009). Initially, acute or chronic lead poisoning was recognized by the association of high blood Pb2+ levels with non-specific signs and symptoms (Patrick 2006b). The blood threshold limit for safety to lead exposure has been estimated at 10 μg/dl, but, as our knowledge increases, there appears to be no apparent threshold for safety to lead exposure (Vorvolakos et al. 2016). Many studies on lead toxicity have focused on its neurotoxicity and effects on cognitive development and intellectual impairment in children (Bellinger et al. 1987; Canfield et al. 2003; Lidsky and Schneider 2003).

While it can be hypothesized that lead exposure affects heart functioning, lead cardiotoxicity has been largely overlooked. Pb2+ exhibits some chemical similarities with calcium ion (Ca2+) that can help to explain the molecular mechanisms of lead toxicity and why the former is toxic, whereas the latter is not (Kirberger and Yang 2008; Simons 1992). The Shannon effective ionic radius is similar in both metal ions (1.14 Å for Ca2+ compared to 0.95 to 1.33 Å for different ionic forms of lead) in solution (Shannon 1976). This has been attributed to the lanthanide contraction of electron orbitals due to the poor shielding of the nucleus by the 4f14 electrons (Housecroft and Sharpe 2012). In addition, like Ca2, Pb2+ exhibits a face-centered cubic structure, resulting in the same coordination number (8) (Schwerdtfeger 2002). Finally, their charge-to-ionic radius ratios are also similar (1.79 for Ca2+, 1.55 for Pb2+) (Schwerdtfeger 2002).

Many of the effects of lead toxicity are due to the fact that, because of its similarity with Ca2+, Pb2+ can interfere with many intracellular processes in which Ca2+ is involved, for example, as a second messenger (Bressler et al. 1999; Simons 1986, 1992). This may be due to an important molecular feature, the similarity of the electron orbitals of Pb2+ and Ca2+ that has been implicated in lead toxicity. For example, the outer shell electrons orbitals are 4s2 for Ca2+ and 6s2 and 6p2 for Pb2+. It is easier for lead to lose the s orbitals, resulting in the most common oxidized state of +2, instead of +4. However, due to its different atomic number, Ca2+ has only underlying 3p6 electron orbitals, whereas Pb2 has low-lying p plus d orbitals (6p2, 5d10 and 5p6) (Haynes 2016). Due to this difference, Pb2+ has a greater tendency than Ca2+ to form strong bounds with anions and specific elements (Martell and Smith 1974; Nieboer and Richardson 1980; Sillen et al. 1964; Simons 1986, 1992). This is particularly relevant to nitrogen and sulfur atoms in biomolecules, as they are particularly susceptible to form covalent bonds with Pb2+. Because of this, Pb2+ can modify biomolecules, resulting in another molecular mechanism that can result in lead toxicity. Finally, biochemical reactions promoted by exposure to heavy metals, in general, are particularly important in generating cellular free radical oxidants (Dietz et al. 1999; Lopes et al. 2016; Patrick 2006a).

Utilizing the various mechanisms stated above, Pb2+ can interfere with ion channels, receptors and transporters, altering intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, and these actions can explain, in part, the pathogenesis of lead poisoning and its production of symptoms in animals and humans (Atchison 2003; Audesirk 1993; Oortgiesen et al. 1993). Thus, lead ions can alter the direct function of ion channels by binding to calcium affinity sites or by redox modification (Atchison 2003; Lopes et al. 2016). Neurotoxicity of lead exposure has been extensively studied and many ion channels, receptors, transporters and pumps have been directly or indirectly implicated in lead toxic effects (Baranowska-Bosiacka et al. 2012; Kursula and Majava 2007; Neal and Guilarte 2010).

It has been reported, mostly from experiments in isolated neurons, that voltage-dependent calcium channels (VGCC) can be directly affected by lead ion exposure (Atchison 2003; Bernal et al. 1997; Busselberg 1995; Busselberg et al. 1994b; Peng et al. 2002). In addition, lead ions can directly bind to calmodulin (Kursula and Majava 2007; Wilson and Brunger 2003), and calmodulin has been implicated in the ion-dependent inactivation of L-type calcium channels (Halling et al. 2005; Qin et al. 1999; Zuhlke et al. 1999). However, detailed studies of lead exposure on inactivation or gating currents of these channels have not been conducted. Lead ions do not irreversibly block VGCC, and in some cells VGCC have been reported as one of the main pathways of cellular entry of lead ions (Simons and Pocock 1987).

Other calcium permeable channels have been studied as targets during lead poisoning, especially in the central nervous system. NMDA receptors are known to be inhibited by lead ion exposure, resulting in memory problems related to long-term potentiation and cognitive dysfunction (Busselberg et al. 1994a; Cory-Slechta et al. 1997; Gavazzo et al. 2001; Guilarte 1997; Karri et al. 2016). Pb2+ has been shown to enter cells through TrpC1 channels as well as playing a role in stimulating TrpC5 channels at extracellular concentrations around 1 μM (Sukumar and Beech 2010; Zhang et al. 2014). Other channels reported as pathways of entry of Pb2+ into cells are the store-operated Ca2+ channel complex Orai1-STIM1 (Chiu et al. 2009). TrpM channels can be completely blocked by concentrations of Pb2+ around 10 μM (Sukumar and Beech 2010). Voltage-gated sodium channels in hippocampal CA1 neurons have also been shown to be inhibited and inactivated by Pb2+ concentrations around 100 μM, (Gu et al. 2005; Yan et al. 2008). The effects on sodium channels due to chronic Pb2+ exposure during development in rats has been studied by Yan et al. (2008). Lead ions have also been reported to reversibly inhibit delayed and transient outward potassium currents in hippocampal neurons (Madeja et al. 1995, 1997; Yu et al. 2003). These effects were found in both steady-state activation and inactivation experiments (Madeja et al. 1997; Yu et al. 2003); however, similar findings were not observed in Kv channels from outer hair cells (Liang et al. 2004). In addition to the NMDA receptor, acute lead exposure has been reported to modify the action of other receptors by modifying their function and also reducing their expression levels during chronic exposures (Marchetti 2014; Vijverberg et al. 1994b).

Susceptibility to lead poisoning is particularly important during early development, because the brain structure is not yet mature, and lead ions can more easily penetrate the blood–brain barrier (Goasdoue et al. 2016). After its entry into the central nervous system, lead can be found stored in glial cells, affecting nearby neurons and synaptic transmission (Baranowska-Bosiacka et al. 2012; Marchetti 2014). Initial reports concluded that dopamine receptors are not modified by lead (Winder and Lazareno 1985); however, subsequent studies found changes in these receptors during chronic exposure to lead. Dopamine receptors in the mesocorticolimbic pathway are altered by Pb2+, leading to hyper- or hypo-dopaminergic responses related to the timing of lead exposure and its effects on different regions of the mesocorticolimbic pathway (Gedeon et al. 2001). More recently, these changes have been speculated to play a role in the development of schizophrenia (Stansfield et al. 2015). Similar to glutamate receptors (especially NMDA receptors), GABA receptor functioning and GABA release at presynaptic locations are impaired by lead exposure, either in their excitatory phase during development or at later stages in life (Stansfield et al. 2015; Wirbisky et al. 2014; Xiao et al. 2006; Zizza et al. 2013). Inhibition of GABA release can be linked to VGCC blockage by Pb2+, and this has been proposed as a possible explanation for cognitive disorders caused by lead exposure (Xiao et al. 2006). In addition, nicotinic cholinergic receptors (nACh) in the rat hippocampus have been shown to be affected by lead, resulting in lead ion activation of PKC, which in turn inhibits the function of nACh ligand gated channels, affecting excitatory as well as inhibitory pathways involving glutamate and GABA release (Braga et al. 2004). The direct blocking effects of lead ions on nACh have also been reported (Oortgiesen et al. 1990). Exposure to lead ions in structures of the mesolimbic pathway in rats during early development also stimulated or inhibited the function and the expression of purinergic receptors in distinct ways for different regions of this pathway (Baranowska-Bosiacka et al. 2016).

Several membrane ion transporters have been implicated in the uptake of lead ions into cells. Among these are the divalent metal transporters or DMT1 transporters. In astrocytes, in addition to DMT1 transporters, pH-sensitive transporters have also been implicated in lead toxic effects (Bressler et al. 2004; Cheong et al. 2004). Lead toxicity in astrocytes may also influence the metabolism of neurons through interactions with glutamate transporters (Struzynska 2005, 2009). In addition, zinc transporters may also play a role in lead toxicity, by increasing cellular uptake of Pb2+ (Fu et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2007). In yeast and plants, which store Pb2+ in lead-polluted environments, P1B-ATPase and ABC transporters appear to play a role either in the uptake of lead ions or in lead detoxification through vacuolar transport inside these cells (Gravot et al. 2004; Sousa et al. 2015). Aquaporins may also play a role in lead accumulation in vegetables and some marine animals (Amado et al. 2012; Przedpelska-Wasowicz and Wierzbicka 2011). Differential effects of Pb2+ have been reported regarding Na+/K+ pump activity in different cells (Fox et al. 1991). Although the binding affinities for Na+ and K+ are not affected, exposure to Pb2+ seems to restrict the pump to a phosphorylated state (the E2 conformational state) (Bartolommei et al. 2010).

Pb2+ interferes with calcium homeostasis mechanisms by altering Ca2+ channels that are also pathways of lead ion cellular uptake or by effects on intracellular Ca2+ channels and transporters. The interference of Pb2+ with intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis has been previously recognized (Pounds 1984; Simons 1986, 1993). These effects were proposed, in part, to be due to the shared affinity of Ca2+ and Pb2+ by the same binding sites in Ca2+-binding proteins and enzymes (Goering 1993; Gorkhali et al. 2016; Habermann et al. 1983; Kirberger et al. 2013; Kirberger and Yang 2008; Ouyang and Vogel 1998).

Bones are also an important target during lead poisoning, as lead ions can be stored in bones by displacing Ca2+ and interfering with the normal metabolism of bone cells (Rosen and Pounds 1989). In many cells, such as endocrine and smooth muscle cells, calcium-activated potassium channels participate in the mechanisms of calcium homeostasis (Orio et al. 2002). The effect of lead ions in small, intermediate and large conductance calcium-activated K+ channels seems to be different among various isoforms in diverse cell types (Vijverberg et al. 1994a). A precise oscillation of Ca2+ is needed for the normal development of embryos in many animals (Armant 2015). For example, it has been reported in zebrafish that lead ions interfere with this process, leading to abnormal embryo development (Chen et al. 2009).

Normal heart function critically depends on good temporal and spatial correlations between ion channels, transporters and intracellular Ca2+. As such, these channels and transporters are likely targets during lead poisoning. Moreover, there are some clinical reports about heart effects seen during lead poisoning, but there are only a few studies that have attempted to understand the effects of lead exposure in the heart at the molecular level (Basha et al. 2012; Bhatnagar 2006; Kurppa et al. 1984; Missiaen et al. 2000; Scoote and Williams 2004; Silva et al. 2015; Taylor 1996; Tollestrup et al. 1995; Williams et al. 1983). In this paper, we study the effects of Pb2+ on contractility, heart rate and arrhythmias in isolated heart cells from guinea pigs and mice. We also report the effects of acute lead ion exposure of the Cav1.2 L-type calcium channels in the heart. We show that acute exposure to inorganic Pb2+ (in the concentration range 0–100 μM) has negative inotropic effect, such as incremental effects on diastolic pressure and arrhythmic patterns, in isolated guinea pig hearts. We also show that Pb2+ in the same concentration range blocks L-type Cav1.2 channels and increases their fast inactivation. In addition, action potentials are reduced in amplitude and elongated in the presence similar concentrations of lead ions. These findings show that the heart could be an important Pb2+ target, especially during acute exposures to lead. Therefore, we suggest that heart function must be clinically monitored in these situations, especially when the levels of free Pb2+are likely to be relatively high, in the range of μM.

Alterations in cardiac function produced by acute exposure to Pb2+ in isolated guinea pig hearts

Guinea pigs weighing approximately 300 g were sacrificed according to bio-ethical procedures accepted by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Sciences (IACUC/AALAS). The protocol was submitted and approved by the Uruguayan Honorary Committee on Animal Ethics (CHEA) (Application 071140-001788-09). To avoid suffering, the animals were sacrificed by fast cervical dislocation. This procedure had to be used, because anesthetics can alter functioning of the hearts to be isolated, producing an artificial cardiorespiratory depression (Heavner 2002). Hearts were rapidly removed from the animals (in less than 1 min), and the aortas were perfused with a gravity-driven coronary retro-perfusion system (50–80 mmHg) using Tyrode’s solution with 1.8 mM Ca2+ warmed to 37 °C and bubbled with oxygen at a constant pressure of 50–100 kPa as described in Costa et al. (2014). After cannulating the heart, the removal of blood from the coronary arteries was monitored. Tyrode’s solution flow varied between 12 and 18 ml/min. After the hearts were stable, a tiny incision that did not damage heart vessels was made in the left wall of each heart. A small clip was fixed and connected from the base of the papillary muscles to a FT-03 transducer with an inextensible thread to measure tension (Grass Astromed). Electrical records were obtained with two non-polarizible Ag+/AgCl electrodes positioned at both ends of the papillary muscle. Alternatively, platinum electrodes were used. If required to initiate a particular fixed beating frequency, stimulating electrodes were added. The signals were amplified 100 times and filtered at 10–100 Hz after acquisition through a Mini-Digi Model 1A at 1 KHz using an Axoscope Model 9.2 (Axon Instruments, now Molecular Devices). Data was analyzed with Clampfit (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices) and later processed with Sigma SYSTAT software. Results corresponding to the same type of experiment are shown as mean ± SEM. This procedure allowed us to monitor heart function simultaneously by their contractility and excitability.

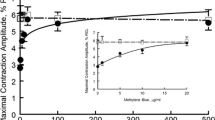

To explore the acute effects of lead ions on isolated hearts, inorganic Pb2+ (as PbCl2) was added to Tyrode’s solution at different concentrations. In Fig. 1a, the effects of applying different concentrations of PbCl2 on the inotropism/contractility of the isolated hearts are shown. Increasing concentrations of Pb2+ (1-200 μM) decreased the amplitude of the contractile force recorded at the papillary muscle, measured as tension to normalize force for different surfaces of muscles (force/surface of recording). These results were also obtained when monitoring tension in other regions of the isolated heart or the whole heart (data not shown). Isolated hearts were allowed to beat at their own pace in this set of experiments. After applying each dose of extracellular Pb2+, we waited long enough for the hearts to equilibrate, usually 5–10 min, so that we could record during a period that their contraction patterns were stable. We then explored the effects of different concentrations of Pb2+ on the amplitudes of contraction. It is interesting to note that at relatively low concentrations of Pb2+ (1–20 μM), the contraction patterns lost their amplitude stabilities over time. At higher concentrations of Pb2+ (>100 μM), the contraction amplitudes diminished even more, and, at doses above 200 μM of Pb2+, 40% of the hearts underwent cardiac arrest. In Fig. 1b, a dose–response curve of the amplitude of contraction versus lead concentration is shown for isolated hearts (n = 6). The amplitude of contraction was found to decay monotonically with increasing concentrations of extracellular Pb2+. The midpoint of inhibition where 50% of the amplitude was lost occurred at approximately 50–70 μM Pb2+. To confirm this, a Hill equation was used to generate a dose–response curve from the data, where R = Ro + [a* d^h/(IC50^h + d^h)], and R and d are response and dose, respectively, h is the Hill coefficient, a is the maximal variation, and Ro is the asymptotic level. From the Hill equation, an IC50 (half-maximal effect of Pb2+ concentration) could be estimated at approximately 55 μM and an h of approximately − 2.

Acute exposure to inorganic lead ions has a negative inotropic effect on isolated guinea-pig hearts. a Recordings of tension at the base of the papillary muscle versus time after application of different concentrations of extracellular Pb2+. The Pb2+ was added to the extracelular perfusion solution (1.8 mM Tyrode’s solution). Application of 20 μM Pb2+ causes appearance of contractions at various times with varying amplitudes. The overall average amplitude diminishes with increasing extracelular lead. b Dose–response curve of force amplitude of contraction versus extracelular Pb2+ concentration. There is also a monotonic decrease of force, measured as tension, with increasing Pb2+ concentrations. Symbols represent average values with standard error bars (n = 6). The solid line corresponds to the best fit of a Hill equation of the type F = Fo + AF. D^h / (IC50^h + D^h), where h is the hill coefficient, IC50 is the half-dose for the observed effect, Fo is the minimal force, AF is the maximum observed variation in force (force initially at dose 0−Fo at maximal dose), F is force amplitude and D is the concentration of extracellular lead ions

Using isolated hearts from neonatal rats fed with Pb2+, Williams et al. (1983) reported a negative effect on heart contractility (inotropism). However, in the Williams et al. (1983) experiments, exposure to Pb2+ could have indirectly altered heart function due to its reported neurotoxic effects. In our experiments we can eliminate that possible explanation, because the Pb2+ was directly applied onto the isolated hearts and was not fed to the intact animals. Moreover, in lead-treated Wistar rats, chronic exposure to Pb2+ resulted in changes in myocardial contractility, although these changes were not as dramatic as those seen in acute lead exposures (at higher Pb2+ doses). This work also mentioned the possibility that lead exposure causes deleterious effects on blood vessels (Fioresi et al. 2014; Simoes et al. 2011). The reported effects from chronic Pb2+ exposure can take place with variations (or not) in the diastolic tension. Incremental changes in diastolic tension suggested that there were changes in intracellular Ca2+ and/or effects of lead on promoting direct interactions between actin and myosin, or other possible effects.

In a series of experiments on isolated hearts extracellular Pb2+ was increased from 0 to 100 μM, and the effects of Pb2+ on diastolic tension, contractile activation-relaxation and heart rate were recorded (Figs. 2, 3, 4). For example, a plot of force amplitude versus time revealed the effects of Pb2+ on heart rate in a low-time resolution plot is shown in Fig. 2, in which heart contractions are presented as thick lines. The red vertical line indicates the time at which Pb2+ was first placed into the extracellular solution. This experiment was performed by increasing Pb2+ concentrations in 20-μM increments every 10 s until a concentration of 100 μM Pb2+ was achieved, or after a total of approximately 50 s. The lower level of contraction amplitude represents the basal diastolic tension. It can be seen that extracellular application of Pb2+ increased the basal tension and that a stationary level was achieved quite rapidly after the extracellular application of Pb2+ (50–60 s, almost simultaneously with the added increments of extracellular Pb2+). After a stationary level was reached (after the application of 100 μM Pb2+), the irregularities in amplitude of force contraction described above were seen quite frequently as different alternating peak amplitudes. This effect of Pb2+ has not been thoroughly studied. There are a few reports regarding the inhibition of the ATPase cycling rate by Pb2+ in actomyosin complexes isolated from the smooth muscle of uterus after oral lead administration (Dabyntseva et al. 1995; Labyntseva et al. 1998). This would be consistent with our findings in isolated hearts, although the changes in resting tension could also be due to incremental changes in resting intracellular Ca2+ concentrations due to increasing Pb2+ concentrations. Both explanations are possible and not mutually exclusive.

Increasing the extracelular Pb2+ concentration increases the resting diastolic tension in isolated hearts. Recordings of amplitude of contraction versus time are shown at low temporal resolution in order to demonstrate the behavior of minimal levels of tension during the application of extracellular Pb2+ (at 0–100 μM). Extracellular Pb2+ was applied after the red line. Concomitantly, the resting level of basal diastolic tension increased until it reached a stationary value, which was higher than the one observed in the control (before the red line). Interestingly, the appearance of the contractions after reaching the stationary value are also more spread out and unpredictable with respect to their high and low values when compared with the control

Analysis of the first derivative of tension versus time plots (dT/dt) of a typical control and Pb2+-treated hearts are shown in Fig. 3. The first derivative of the contractile activity represents the velocity of contraction for the activation and deactivation of contractility, respectively. This was obtained by numerical calculus using a program we developed under Sigma SYSTAT software, or lim h→0 [f(x + h)-f(x)/h]. The upper part of Fig. 3a represents the traces in controls as a cloud of data points and as a line for the average filtered signal for eight superimposed representative traces. This procedure was done to minimize noise in the primary data and to obtain a first derivative of these data devoid of the usual noise. As shown in the lower part of Fig. 3a, the horizontal line corresponds to a first derivative equal to zero, and as such it will be reached during the peak of the contraction and also when full relaxation without appreciable variation of tension begins. The vertical lines indicate particular moments of correspondence between the contraction and first derivative data (lines b, d, f in Fig. 3a when the first derivative is zero). Note the correspondence between the primary recording of maximal (positive) activation velocities and the minimal (negative) velocities with the first derivative data (lines a, c, e and g in Fig. 3a). The maximal and minimal velocities for activation and relaxation correspond roughly to the primary data slopes at the times of half-activation and half-relaxation, respectively. In Fig. 3b similar data are shown when 80 μM Pb2+ is added to the extracellular solution. The upper trace of Fig. 3b shows the average primary record (average of 8 traces) of tension versus time. In the lower part of Fig. 3b, the first derivative is shown as a horizontal line, and the vertical lines are similar to those presented in Fig. 3a. Both velocities are reduced by the presence of 80 μM Pb2+, although the effects are more dramatic for activation than for relaxation (for example, compare the maximal and minimal velocities in control and lead-treated hearts, 20% for maximal velocities compared to 40% for minimal velocities).

Acute Pb2+ exposure modifies the velocities for contractile activation and relaxation. a Upper panel Control recordings of tension versus time. The thick line represents the average filtered trace (n = 8). The dots represent several control contractions for this particular heart. Lower panel The first derivative dT/dt of the record shown in (a) was calculated using numerical calculus. The horizontal line corresponds to zero. The vertical lines show that the maximum velocity of contraction occurs at half-activation (a, e). The peak of contraction and the lowest diastolic tension corresponds to zero (b, d, f), and the minimal (negative) velocity occurs approximately at the time of half-deactivation of the contraction (c, g). b Upper panel The tension recordings are as in (a), but with Pb2+ at 80 μM. Lower panel Same as in (a, lower panel), except with 80 μM Pb2+. The horizontal line corresponds to zero and the letters at each of the vertical lines have the same meaning as in (a). Note that exposure of the isolated heart to Pb2+ at 80 μM affects both activation and deactivation velocities, but the effect is more dramatic on the velocity of activation

Activation of contraction is related to Ca2+ release from the SR, diffusion to the sarcoplasm and binding to troponin C, whereas relaxation is related to Ca2+ pump activity by SERCA inside the SR, Ca2+uptake by mitochondria, and Ca2+ extrusion to the extracellular media (Dibb et al. 2007). This suggests that the release of Ca2+ from the SR is more likely affected by Pb2+ than the mechanisms that remove Ca2+ from the sarcoplasm. It is also consistent with findings in other cell types where Pb2+ was found to increase Ca2+ release (Gorkhali et al. 2016; Jang et al. 2008; Sandhir and Gill 1994; Wang et al. 2015; Westerink and Vijverberg 2002) and a report related to chronic lead exposure to rat hearts (Fioresi et al. 2014).

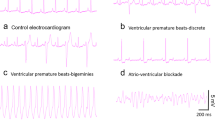

To determine roughly how the whole isolated heart can be affected by acute Pb2+ exposure, we measured the electrical activity. Figure 4 shows simultaneous recordings of monophasic action potentials in the papillary muscle and how electrical activity, such as heart rate and likelihood of obtaining arrhythmias per analyzed bins, are affected by acute extracellular Pb2+ exposure. To obtain compound monophasic action potentials one electrode was kept active on one end of the papillary muscle, while the other was connected to ground at the other, damaged end of the muscle. This was arranged to follow a parallel array of cylindrical fibers with cardiomyocytes (Jochim et al. 1935; Yang and Kittnar 2010). Simultaneous recordings of monophasic action potentials and tension versus time are shown in a control and an experiment with extracellular Pb2+ at concentrations of 10 and 50 μM (Fig. 4a). With increasing Pb2+ concentrations, the basal tension increases and the amplitude of the contractions diminishes, consistent with data shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Monophasic action potentials also changed their shape. At 50 μM Pb2+, the plateau almost disappeared, the action potentials lasted longer and their amplitudes were lower. This result suggests that Pb2+ blocks Cav1.2 channels, and, at higher doses, possibly K+ channels as well. These results are consistent with previous reports using other cell types, and can explain the toxic actions of lead (Atchison 2003; Liang et al. 2004; Madeja et al. , 1997; Peng et al. 2002; Yu et al. 2003).

Extracellular lead ion affects heart rate in a dual dose-dependent manner and makes the heart susceptible to arrhythmias. a Simultaneous recordings of tension and monophasic action potentials in isolated hearts. At higher doses of extracellular Pb2+ early after-depolarizations are frequent, yielding contractions altered in amplitude and time. b The heart rate increases with increasing concentrations of Pb2+ at low dose levels but diminishes with increasing concentrations of Pb2+ above 20 μM (n = 8). c Anomalous heart beats indicative of the susceptibility of the heart to arrhythmias, such as early after-depolarizations, increase quite significantly at concentrations of Pb2+ above 20 μM (n = 8)

We found that heart beat rate increases at intermediate Pb2+ concentrations and diminishes at higher doses (Fig. 4a). Anomalous heart beats that yield irregular contractions with time, and/or amplitude changes, occur with increasing concentrations of Pb2+. For example, at 50 μM Pb2+ early after-depolarization, irregularities appear quite frequently, and isolated hearts are prone to arrhythmias (Weiss et al. 2010). In Fig. 4b, the dependence of heart beat rate with respect to extracellular lead concentration is shown for 6 isolated hearts. The heart rate is initially increased by extracellular lead in the concentration range of 1–20 μM, but at concentrations above 20 μM Pb2+ it begins to decay below the control heart rate. Concomitantly, the shapes of monophasic action potentials change at Pb2+ concentrations below 20 μM, losing completely their plateau values above 20 μM Pb2+. This result suggests that Pb2+ blocks Cav1.2 channels, similar to what has been reported in other cell types (Atchison 2003; Peng et al. 2002; Prozialeck et al. 2008). It may also suggest that, at doses of Pb2+ above 20 μM, there could be blockage of HCN channels at the sinusal nodes, although this has not yet been examined. The only indirect evidence in agreement with this result is that exposure to lead during rat development increases the threshold to seizures provoked by chemicals (Chen and Chan 2002).

During the repolarization or resting periods heart after-depolarization events can be observed more frequently as the extracellular concentration of Pb2+ is increased (Fig. 4). For example, in Fig. 4c, the average numbers of anomalous events per bin are plotted against the extracellular concentration of Pb2+. Increasing extracellular lead increases arrhythmias in the range of Pb2+ concentrations of 10–100 μM. In parallel to these acute effects by Pb2+ that are likely explained by their effects on ion channels, receptors and transporters, there have been reported metabolic changes in hearts due to Pb2+, especially after chronic exposure to lead (Ansari et al. 2013; Kopp et al. 1980). In summary, in this section, we have reported our findings on how cardiac function is affected by the acute exposure to Pb2+ in isolated guinea pig hearts.

Extracellular Pb2+ blocks Cav1.2 channels in isolated cardiomyocytes

The data from isolated hearts, like those presented in Fig. 4, suggest that Pb2+ blocks currents through Cav1.2 channels (ICa). To test this hypothesis, we isolated cardiomyocytes from guinea pig hearts, recorded ICa, and then applied extracellular Pb2+ to the cells and measured ICa. Myocytes were isolated using the methods of Mitra and Morad with minor modifications (Ferreira 1992; Ferreira et al. 1997a; Mitra and Morad 1985). The solutions used for myocyte isolation and Pb2+ exposure are described in Ferreira et al. (1997a). After rinsing, the enzymatically treated isolated hearts in Tyrode’s solution with 0.2 mM Ca2+, the tissue was minced into 1-mm slices at 37 °C in the same solution. Cells were dispersed by agitation at 37 °C for 5–10 min under bubbling O2, and the released cells were then forced through a 200 × 200 μm mesh and placed in petri dishes with Tyrode’s solution containing 1.8 mM Ca2+ at room temperature. Extracellular Ca2+ was increased to 5 mM before patching, and then switched back to the normal Tyrode’s solution with 1.8 mM Ca2+. The cells were placed into a chamber on an inverted microscope, and effective cell isolation was estimated in normal Tyrode’s solution as the percentage of rod-shaped striated cells divided by the total number of cells counted per field using an average of 10 fields. It was routinely 40 ± 8%. An extracellular perfusion system was devised in order to obtain laminar flow of extracellular solutions immediately on the surfaces of the patched cells. Whole-cell patch clamp was accomplished using rod-shaped cardiomyocytes, following the usual procedures described for patch clamping (Hamill et al. 1981; Sakmann and Neher 2009). To record ICa, extracellular solutions were normal Tyrode’s solution with 1.8 mM Ca2+ (control or reference situations) and normal Tyrode with 1.8 mM Ca2+ plus various concentrations of PbCl2. We also used extracellular and intracellular solutions as described in Ferreira et al. (1997a). Pipettes were prepared from borosilicate glass without filaments (Corning 7052–7056) in a Sutter puller (Model P-2000) and polished with a Narishige microforge (model MF-900). When the prepared pipettes were filled with the intracellular or extracellular solutions, they had a resistance of 1-3 MΩ. The time constant for clamping under these conditions was approximately 0.8 ms. Pipettes were held in a head stage of 500 MΩ resistance connected to a patch clamp amplifier (AM-Systems 2400). Recordings were acquired with a Digidata Model 1322A (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices), using pClamp 9 (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices). Sampling frequency varied between 10 and 20 Khz, and records were filtered at 5 KHz. Control pulses were obtained with a P/4 protocol from a holding potential of − 90 mV. After the data were collected, they were analyzed with Clampfit (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices) and later processed with Sigma SYSTAT software.

The results of applying 30 μM Pb2+ to the isolated guinea pig cardiomyocytes and measuring ICa through Cav1.2 channels are shown in Fig. 5. The pulse protocol is shown in Fig. 5a. The holding potential was − 90 mV. To eliminate sodium ion currents (INa), we applied a 50 ms prepulse at − 40 mV. To record ICa near its maximum peak, pulses were applied from − 40 to 0 or + 20 mV (Ferreira et al. 1997a, b). In Fig. 5b, the ICa elicited by pulses from − 40 to + 20 mV are shown from the initial control, to the traces found with 30 μM Pb2+ (Fig. 5b, left panel). In agreement with our hypothesis and the results found with isolated guinea pig hearts, ICa was blocked or reduced significantly by 30 μM Pb2+. Since we placed a microperfusion pipette on top of the patched cells under laminar flow, the extracellular perfusion exposed the cells to Pb2+ almost instantaneously. Washout from a Pb2+extracellular solution to a normal reference Tyrode’s solution showed that lead blockage of Cav1.2 channels is fully reversible (Fig. 5b, right panel). It is interesting that the kinetics of the current by the end of the pulse appears to be different compared to reference and washout traces. This could be explained by interference of Pb2+ with the inactivation mechanisms of Cav1.2 channels, or by its effect on outward currents by the end of the pulse (for example, by blockage of K+ currents). In addition, there could be other non-inactivating currents superimposed on the ICa trace. These did not seem to significantly interfere with our results on this time scale, because replacing K+ with methansulfonate did not change dramatically the appearance of the currents and their Pb2+ blockage. The kinetics of blockage and washout are shown in Fig. 5c. After a few seconds of exposure to extracellular Pb2+, ICa reached a stationary stage of inhibition, suggesting the direct interactions of Pb2+ with the Cav1.2 channels. As suggested in previous reports, part of the mechanism of toxicity of Pb2+ is likely due to its similarity with Ca2+, and its ability to substitute for Ca2+ in Ca2+-binding sites of different Ca2+-binding channel pore proteins (Gorkhali et al. 2016; Kirberger et al. 2013). The Cav1.2 channels are in such a group of Ca2+-binding channel pore proteins (Neumaier et al. 2015). The fact that the channels are blocked by Pb2+ suggests that the permeation pore of Cav1.2 has a stronger affinity for Pb2+ than for Ca2+. Because of an apparent stronger affinity for Pb2+, the ICa can be blocked by extracellular Pb2+. When extracellular lead ions are removed, Pb2+ rapidly leaves the Ca2+-binding site, restoring the Ca2+ permeability through the Cav1.2 channels. In Fig. 5d, a dose–response curve of the normalized ICa peak has been plotted against extracellular Pb2+ concentration. The symbols in Fig. 5d correspond to averages ± SEM (n = 6). The solid line represents the best fit of a Hill equation. Values for the parameters from the best fit of the Hill equation were 18 ± 8 μM for the IC50 and − 1.28 for h, the Hill coefficient. These values are lower than those reported for the inotropic negative effects of lead ions in isolated hearts (see Fig. 1), suggesting that blockage of ICa by lead ions explains partially the negative inotropic effects of Pb2+. The properties of Pb2+ on other Ca2+−dependent receptors and transporters are likely implicated by our data. Although the IC50 values are somewhat higher for Cav1.2 channels in neurons and in HEK293 cells (~ 1.5 μM) compared to those found here for isolated cardiomyocytes, a likely explanation is that the dose–response curves from the former were determined using Ba2+ not Ca2+ in the supporting solutions (Marchetti 2013). The affinity of Ba2+ for the ion permeation pathway and selectivity filter of Cav1.2 channels is less than for Ca2+(Li et al. 2010). Another possible explanation could be that the auxiliary subunits of Cav1.2 channels in neurons and in the heart are different. If this is true, it would imply that Pb2+ at the concentrations we used may affect not just the main subunit of Cav1.2 channels, but also their auxiliary subunits. This could add diversity about targeting of Cav1.2 channels by Pb 2+ and the observed toxic effects in different cells expressing distinct auxiliary subunits. It is also interesting to note that many blockers of Cav1.2 channels possess high affinities for the pore, and they actually can permeate the channel but at a much lower rate, yielding low channel currents (Hess et al. 1986; Lansman et al. 1986). This would implicate, as it has been proposed in other cells, that VGCC can be pathways for entry of Pb2+ into the cardiomyocytes (Legare et al. 1998; Tomsig and Suszkiw 1991).

Addition of lead ions in the micromolar range to the reference Tyrode’s solution with 1.8-mM calcium blocks currents through Cav1.2 channels in isolated cardiomyocytes. a Pulse protocol to record ICa from a holding potential of − 90 mV. A short 50 ms pre-pulse to − 40 mV was applied in order to inactivate sodium channels. The pulse from − 40 to + 20 mV records mostly ICa. b Recordings elicited by repeatedly applying pulses from − 40 to 20 mV while 30 μM Pb2+ was added to the reference Tyrode’s solution. The addition of Pb2+ promotes a blockage of ICa (left panel). This blockage was not irreversible, as washing-out or removing extracelular Pb2+ and returning to the reference Tyrode’s solution augmented ICa (right panel). The kinetics of the current in the reference Tyrode’s solution before addition of Pb2+and after the addition of lead ions seems to be slightly different (right panel). c Time course of experiments similar to those reported in (b). The peak of ICa elicited by the repetitive pulses from − 40 to + 20 mV is plotted against time in reference Tyrode’s solution, after addition of 30 μM Pb2+ and after washing-out the lead ions. The onset kinetics of blockage is quite fast, taking place in less than 20 s. The same applies to the kinetics of washing out the Pb2+ from the extracellular Tyrode’s solution. d Dose–response curve of the normalized ICa peak (ICa/ICa max) versus dose of extracelular Pb2+. The symbols represent the average values for each dose (n = 6). The solid line represents the best fit of Hill equation to the data. Main parameters of the best fit were IC50 ~ 18 μM and h ~ −1.3

Extracellular Pb2+ enhances inactivation of currents through Cav1.2 channels in isolated cardiomyocytes.

After establishing that Pb2+ blocks ICa through Cav1.2 channels in isolated cardiac myocytes, we then sought to determine if lead ions could affect the gating machinery of these channels. To accomplish this, we designed an experiment to test how activation and inactivation of Cav1.2 channels could be affected by extracellular Pb2+. In the pulse protocol (shown in Fig. 6a), we applied a 50-ms pre-pulse to − 40 mV from a holding potential of − 90 mV to eliminate the INa+ signal. Further stimulus test pulses were applied from − 40 mV in steps of 10 mV from − 60 to + 60 mV (arrows) to test ICa at different voltages on a classical current–voltage (I–V) curve. To eliminate the capacitive currents, pulses were also applied from a holding potential of − 90 mV following the P/4 classical procedure and substracted from the test pulse for ICa to obtain the ICa without capacitive currents. In Fig. 6b, theI–V curves for ICa are shown in controls (Fig. 6b, left panel) and after the addition of 30 μM Pb2+ (Fig. 6b, right panel). Pb2+ blocked ICa at all potentials tested in this experiment. The maximal peak of ICa was found at 0 or +20 mV in reference experiments (n = 8). When 30 μM Pb2+ was added to the reference solution, ICa was inhibited at all potentials tested, and there was a slight shift of the maximal ICa peak towards positive potentials (0–10 mV) (Fig. 6d).

Extracellular lead ions reduce activation and increase inactivation of Cav1.2 channels from cardyomyocytes isolated from guinea pig hearts. a Pulse protocol to eliminate the contribution of INa. Using a 50-ms pre-pulse to − 40 mV from a holding potential of − 90 mV inactivates most of the sodium current. From − 40 mV above, the applied stimulus test pulses cause almost exclusively ICa from Cav1.2 channels. b A family of I–V recordings of ICa currents through Cav1.2 channels in reference controls and in the presence of 30 μM Pb2+. c Average I–V curves from recordings of reference controls and in the presence of 30 μM Pb2+ (n = 8). Pb2+ inhibits Cav1.2 channels at all potentials tested. d Steady-state activation curves for the ionic conductance of Cav1.2 channels in reference controls and in the presence of 30 μM Pb2+. The thick solid line represents the best fit of a Boltzmann equation to the data. Lead ions shifted the half-activation Vm from − 20 to approximately 0, and the activation is shallower in the presence of Pb2+. e Inactivation measured as extent of inactivation of a 120-ms pulse at different potentials. Pb2+increased the fast-inactivation process, especially after channel opening at − 40 to approximately − 30 mV

The same type of experiment was conducted in tsA201 and in HEK 293 cells that expressed α1C, β2a and α2δ subunits of the rabbit cardiac Cav1.2 channels (Fig. 7). The membrane conductance for Ca2+ (gCa) was calculated from the I–V curve as well as for measurements from tails. From the I–V curve. it was obtained by the ratio ICa/(Vm-VCa) where Vm is the membrane potential from the applied pulse, VCa is the equilibrium potential for Ca2+ and ICa is the Ca2+ current elicited by the pulse (Vm). From tail currents. conductance was obtained from ICa at the instant of repolarization from the stimulus test pulse (Vm). Normalized average values (gCa/gCamax) for each membrane potential are shown in Fig. 7d. The solid line represents the best fit of a Boltzmann equation to the data. In reference, half activation potential was ~ − 15 mV and the slope was ~2. Consistent with the I–V curves in the presence of 30 μM Pb2+, the half-activation potential was shifted towards more positive potentials (by ~10 mV) and the slope increased to 8. These results suggest that blockage by Pb2+ interferes with the gating activation mechanisms in Cav1.2 channels. The half-activation time for the maximal current was ~12.5 ms in reference controls compared with 17 ms in Pb2+-treated cells. These results are consistent with blockage of the permeation pathway of BK channels by extracellular ions (Pb2+) (Neyton and Pelleschi 1991). As significant blockage occurred above − 40 mV, these data along with interference with the kinetics and steady state activation results are consistent with the hypothesis that most of the Pb2+ blockage takes place during the opening pathway of the Cav1.2 channels. The fact that the steady state activation curve was modified by Pb2+ (both the half-activation potential and the slope factor) suggests that Pb2+ interferes with channel opening, modifying the Cav1.2 voltage sensor or its coupling to the Cav1.2 gate for opening. The extent of inactivation for all ICa recordings at different voltages was plotted against membrane voltage in Fig. 7e. The addition of Pb2+ increased the extent of inactivation by ~60% (from 0.7 to 0.3), particularly at voltages above − 20 mV that open the channels (as in Fig. 7d). The lengths of the pulses were about 120 ms, suggesting that Pb2+ increases a fast inactivation mechanism that could involve ion-dependent inactivation due to its ability to bind to calmodulin and act as an agonist for Ca2+ (Halling et al. 2005; Kursula and Majava 2007). The fast inactivation of Cav1.2 channels also affected their gating currents in a process dependent on the binding of divalent cations (Ferreira et al. 2003). This result implies that. after channel opening, Pb2+ remains in the proximity of the Cav1.2 channel permeation pathway or gating machinery and alters its inactivation properties. In summary, in addition to blocking the Cav1.2 channel, extracellular Pb2+ alters the gating mechanism of these channels, slowing their activation and speeding up their inactivation.

Lead ions enhance the fast voltage-dependent inactivation of cardiac Cav1.2 channels expressed in tsA 201 cells. a A pulse protocol to study the shift of charge distribution promoted by inactivating–conditioning pulses of different lengths of time. The pulse shown with a horizontal arrow on top corresponds to the inactivating-conditioning pulse of varying duration (Tc). After conditioning, a test pulse was applied to record the gating currents. A very short interpulse to − 40 mV was applied to mimick the conditions used to study ICa in isolated cardiomyocytes. The procedure was done in control and in 30 μM Pb2+. b Gating current recordings obtained in control Tyrode’s solution (black traces) and in Tyrode’s solution plus 30 μM Pb2+ (gray traces). The recordings in the upper panel are superimposed with a low temporal gain. Lower panel, the same recording is shown with the OFF trace at a higher temporal resolution. The area under the gating currents corresponds to the charge movement obtained at that particular test pulse. c A plot of half-voltage activation (V1/2) versus conditioning time length (Tc). For each duration of conditioning voltages an entire charge distribution was used, and the half-voltage activation (V1/2) was obtained by the best fit of a Boltzmann distribution. The procedure was repeated for different conditioning lengths of time in control and in 30 μM Pb2+. The solid lines correspond to biexponential fits in control (black) and in 30 μM lead (dark gray). The half-activation potential (V1/2) is shifted towards more negative values by conditioning the pulse more rapidly in the presence of 30 μM Pb2+ than in controls. This result suggests that extracellular lead promotes fast VDI in cardiac Cav1.2 channels

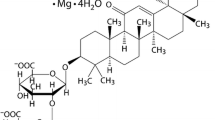

When Cav1.2 channels are inactivated, there is a shift of the half-distribution potential of the charge movement from the voltage sensor that follows a fast and slow kinetics processes. As these inactivation processes affect the movement of the voltage sensor, we have included them in the voltage-dependent inactivation (VDI) (Ferreira et al. 2003). Although it is not clear how fast VDI is related to ion-dependent inactivation, it seems that ion-dependent inactivation can affect gating currents, contrary to what was initially proposed (Babich et al. 2007; Shirokov et al. 1992). Therefore, we tested to see if there was a gating currents shift related to the fast inactivation that was enhanced by Pb2+. Finding this shift could mean that the fast inactivation that it is enhanced by Pb2+ corresponds to fast VDI that could be related to ion-dependent inactivation. In addition, it has been shown that it is dependent on the presence of divalent cations in the permeation pathway (Ferreira et al. 2003). Figure 7 presents experiments with Cav1.2 channels expressed in tsA 201 cells. Transfection was done by traditional calcium-phosphate methods using the Cal-Phos kit (ClonTech), as described previously (Ferreira et al. 1997b, 2003). To record gating currents, we applied a charge solution blocking the Cav1.2 channels with 1 μM Gd3+ as detailed in Ferreira et al. (1997b, 2003). In Fig. 7a, the pulse protocol that monitors the charge movement shift after conditioning inactivating pulses is shown. Stimulus test pulses were applied in charge solution from an interpulse at − 40 mV, and charge movement was measured in the OFF position. In Fig. 7b, the recordings of gating currents in reference controls and in 30 μM Pb2+-treated cells are shown. Below the ON and OFF traces, the OFF traces in reference and in 30 μM Pb2+ are shown superimposed. After the addition of 30 μM Pb2+, the OFF gating currents and charge movements were significantly reduced. The reduction was easily seen for inactivating, conditioning pulses lasting more than 100 ms. In Fig. 7c, the average values of the half-activation potentials obtained for the charge movement distribution after inactivating conditioning pulses are shown. As the length of the conditioning pulses were increased, the half-activation potentials of the charge movement were shifted towards negative values, indicating a VDI process. Most of the difference between the shift of the half-activation potential between reference controls and 30 μM Pb2+-treated cells occurred after 100 ms, and then it stabilized. This result suggested that extracellular Pb2+ enhances VDI and that the promotion of fast inactivation observed in ICa in the presence of Pb2+ (Fig. 6) is at least partially fast VDI, where Pb2+ affects the movement and/or the coupling of the voltage sensor with channel opening. It is interesting to note that the effects of extracellular Pb2+ on inactivation take place under blockage of the channel by Gd3+. This could be explained by sites related to gating of Cav1.2 channels and divalent ion occupancy of the extracellular milieu of the channels (Babich et al. 2005, 2007) and/or by multi-ion occupancy of the permeation pathway by the blocker and Pb2+ (Hess et al. 1986; Lansman et al. 1986). In summary, we found that the enhancement of fast inactivation of the currents by Pb2+ could be explained by the promotion of fast VDI by this metal ion.

A possible mechanistic interpretation of the results of Pb2+ on Cav1.2 channels

The results presented in this paper allow us to speculate that the acute exposure of Cav1.2 channels to Pb2+ is the result of the direct action of lead ions on the channels. This is likely because of the fast kinetics, the way that Pb2+ affects ion and gating currents and the reversibility and of the observed effects. A possible interpretation of the effects of Pb2+ on Cav1.2 channels is presented on Fig. 8. The figure summarizes a possible interpretation of the results we obtained. Fig. 8a, b are the PDB files that have been submitted to NIH regarding the structure of calcium channels (PDB ID 4MVQ) (Tang et al. 2014a). Figure 8a shows the upper view of the Cav1.2 channel according to the structural data. Enclosed in light blue circles delimited by red lines are indicated what are believed to be the pore domain (PD) and the voltage sensor domain (VSD) of the channel and one of the channel repeats, respectively. The PD has the structural underpinnings for the selectivity for Ca2+ of the Cav1.2 channels and the VSD for its voltage dependence. Under discussion is the importance and contribution of the domains from different channel repeats (Zamponi et al. 2015). In Fig. 8b, a lateral view of the structure of the Cav1.2 channel is shown indicating two additional domains, a gate domain (GD), (the lower region pf the PD related to the opening and closing of the channel) and the coupling domain (CD) (a linking structure that couples the VSD with the GD). In Fig. 8c, a scheme is shown indicating all the domains and the possible direct action of lead ions on the Cav1.2 channels. Due to its structural similarity, Pb2+ might interact directly with the PD (shown in purple) or the VSD (shown in red). It has been reported that extracellular Ca2+ affects Cav1.2 gating (Babich et al. 2005) and Pb2+ might substitute for Ca2+ in the ion permeation pathway of the pore domain (shown as gray lines from Pb2+) (Sather and McCleskey 2003; Tang et al. 2014b). The experiments that suggest these possible interactions are those related from Fig. 5, 6, 7. Alternatively, the CD (shown in green in Fig. 8c) might be affected by lead ions if Pb2+ blocks but still permeates the channel in small amounts, as has been reported for blockage mechanisms in several ion channels (Lansman et al. 1986).

Possible sites of interaction of lead ions with the Cav1.2 α1C subunit. a Structural model of the α1C subunit as seen from above, corresponding to PDB ID 4MVQ. Enclosed in light blue circles delimited by red lines are the pore domain (PD) and the voltage sensor domain (VSD) from one of the channel repeats. b Structural transmembrane model shown as a lateral view of the α1C subunit. The arrows indicate the coupling domain (CD) and the gate domain (GD). c. Transmembrane model of the α1C domains and possible sites of interaction of lead ions. The VSD from each repeat is indicated in red. The PD in each repeat is indicated in purple. The lower part of the PD corresponds to the gate domain (GD) and it is indicated by brown double-ended arrows, to indicate the dynamism of that lower part of the pore that fluctuates between closed and open states. The coupling domain (CD) of each repeat is indicated by green. Possible lead ion interactions between the VSD and PD are indicated by dark gray dashed lines with arrows. In the case of the PD, there might be a Pb2+ influx that in turn blocks the channel to the Ca2+ influx (see dark gray arrow). The Calmodulin-IQ C-term region might interact with the I-II linker and/or β subunit. Pb2+ binding to Calmodulin increases then both inactivation mechanisms, fast VDI and CDI

Finally, it is quite interesting that calmodulin binds to an IQ motif in the C-term region of the channel, and this is related to ion-dependent inactivation (CDI) (Halling et al. 2005; Peterson et al. 1999). It is known that lead ions bind strongly to calmodulin and some other Ca2+− binding proteins like Calcineurin, with an agonist effect (Goering 1993; Gorkhali et al. 2016; Kern and Audesirk 2000; Kern et al. 2000; Kirberger et al. 2013; Kirberger and Yang 2008; Ouyang and Vogel 1998). This is a fast inactivation mechanism with a time constant in the order of tens of miliseconds in solutions with Ca2+. We and others have shown that there are at least two voltage-dependent mechanisms (VDI) in Cav1.2 channels. In particular, we have shown how these voltage-dependent inactivayion mechanisms affect Cav1.2 gating currents (Ferreira et al. 1999, 2003). These findings were confirmed later by other groups with different procedures (Hering et al. 2000; Stotz et al. 2000). However, it is unclear how fast VDI and CDI might be related. It is interesting to note that both fast VDI and CDI are dependent on the nature of the permeant ion and on the presence of divalent cations (Ferreira et al. 1999, 2001, 2003). Cav1,2 beta subunits are also able to modify fast VDI (Kobrinsky et al. 2004; Pragnell et al. 1994; Stotz et al. 2000, 2004; Stotz and Zamponi 2001a, b). Thus, we speculate that CDI and fast VDI can be related to the linker between Repeats I and II and that there is a putative interaction between the C-term calmodulin to this region or to the Cav1.2 channel β subunit. The results obtained with lead ions and our previous reports are consistent with this notion (Ferreira et al. 1997b, 1998, 1999, 2001, 2003). If Pb2+ permeates the channel and binds as an agonist to Calmodulin, it is expected that lead ions will increase both CDI and fast VDI, as has been reported in this paper. We did not observe an effect on calcium-dependent facilitation, which has been proposed to be promoted by binding of Ca2+ to two different Ca2+ binding sites, possibly located on the N-terminal lobe of calmodulin binding sites on Cav1.2 channels (Dzhura et al. 2000; Liang et al. 2003; Zuhlke et al. 1999). These sites have different affinities for divalent cations than the ones associated with CDI, located in the C-terminal lobe of calmodulin binding sites in Cav1.2 channels. They also show distinct conformational changes upon divalent cation binding that affect Cav1.2 channel gating in different ways (Findeisen and Minor 2010; Minor and Findeisen 2010; Poomvanicha et al. 2011). These reported differences are a likely explanation for the absence of Ca2+-dependent facilitation by Pb2+.

Finally, we have developed a basic kinetic nine-state model to explain the experimental inactivation of Cav1.2 channel currents and charge immobilization. This model was developed in IDL 7 (Harris Geospatial Solutions/Research Systems), with a system of differential equations that summarizes the possible transitions in the gating pathways. It is described in detail in a previous publication (Ferreira et al. 2003). We used this model to simulate the experimental results obtained with Pb2+. The nine-state model and the mathemathical simulations of ionic and gating currents using this model are shown in Fig. 9. The nine-state model is a basic gating model for the Cav1.2 channels that attempts to explain channel inactivation in ionic and gating currents. In Fig. 9a, the basic kinetic model is presented. It contains a central activation pathway for opening the Cav1.2 channels, with two closed states and an open state. In parallel, there are two inactivation pathways: (1) The fast VDI, shown above the central activation pathway [FAST (a)] in the inactivated states, that is strongly modulated by the presence of divalent cations, and (2) The slow VDI shown below the central activation pathway in the inactivated states [SLOW (b)]. Both processes are reflected as a biexponential decay of the ionic currents and a biexponential shift of the charge distribution of the gating currents. The arrows of various widths indicate the relative speeds of the reaction. The simulated ionic current traces using this model in reference solution and with Pb2+(assuming an affinity approximatey 5-times higher for Pb2+ than for Ca2+) in the O to Ia transition is shown in Fig. 9b. The kinetic constant from O to Ia is increased roughly 5 times by Pb2+. This model also assumes that the affinity of the ion for the pore is 5–10 times higher for Pb2+ than for Ca2+. This results in a reducing and blocking of the current in Cav1.2 channels (see gray or upper trace for the simulation in the presence of Pb2+ and Ca2+ together). As a result, the simulated ionic currents show increased fast inactivation, and they are reduced in magnitude similar to what has been seen experimentally in Figs. 5 and 6. In Fig. 9c, the I-V curves obtained by simulation for the control and experiment in the presence of Pb2+ are shown. Pb2+ reduces calcium currents at all potentials, similar to what we reported in Figs. 5, and 6. In Fig. 9d, the gating currents at high temporal resolution obtained with this model are shown using the same assumptions. The simulation in Fig. 9d reproduces quite well the experimental result shown in Fig. 7.(Ferreira et al. 2003).

A nine-state model with increasing affinity and kinetics for Pb2+ than for Ca2+ for fast inactivation reproduces most of the experimental observations. a Nine-state model. The central pathway accounts for activation with at least two closed states. The upper inactivation pathway with subscript a, represents the fast inactivation process, which proceeds mostly after opening the channel. it is strongly modulated by pore occupancy by divalent or trivalent cations. The lower inactivation pathway (subscript b) represents the slow inactivation process, which proceeds mostly from the open state, but it can also take place in the absence of pore occupancy by divalent or trivalent cations. For the simulations, we assumed roughly a 5-fold higher affinity of Pb2+ ions over Ca2+ ions in the open state. We also assumed that the rate of transition from the open to the fast-inactivated state Ia, was roughly 5 times faster. b Simulated current traces from the model and assumptions explained in (a). In Pb2+, currents are reduced in amplitude and they increase their fast inactivation. c I–V curves for the simulated ionic currents shown in (b) at different voltages. b and c reproduce the experimental findings in Figs. 5 and 6. d Simulated gating currents obtained with the model and assumptions explained in (a). In the presence of Pb2+, gating currents and charge movement are reduced. This simulation reproduces the experimental result shown in Fig. 7

In summary, we have attempted to explain with a structural and a kinetic model the direct effects of Pb2+ on the Cav1.2 channels. These results are interesting in the context of lead poisoning but also in explaining the gating of Cav1.2 channels and its modulation by Pb2+.

Concluding remarks

Here, we have shown that Pb2+ alters cardiac functioning at concentrations in the micromolar range. The maximal values accepted as minimal risk to chronic lead exposure by the WHO are actually around 10 μg/dl (which is roughly 0.5 μM). During acute lead poisoning Pb2+ levels can easily be 10–100 times higher (Findeisen and Minor 2010; Madhusudhanan and Lall 2007; Minor and Findeisen 2010), reaching concentrations between 5 and 50 μM. Most of the research on lead poisoning has focused on its neurotoxic and cognitive effects (Garza et al. 2006; Neal and Guilarte 2010; White et al. 2007). Using isolated guinea pig hearts, which is a good model for the human heart, we found significant effects of low concentrations of Pb2+ on cardiac function that could compromise health via cardiac toxicity. Exposure to extracellular lead ions promoted a decrease in contractility that can be explained by blockage of the L-type Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels. We speculate that the blockage of this current inhibits Ca2+-induced- Ca2+ release (CICR) from the SR, reducing the contractility of the heart. This was also suggested by a reduction of the speed of contraction in the presence of extracellular Pb2+. In addition, extracellular Pb2+ also modified the gating properties of these channels, reducing their activation and increasing their inactivation. This modification of the gating properties of the Cav1.2 channels enhances the inhibition of CICR.

Cardiac excitability was also altered by extracellular Pb2+. Heart beat frequency was increased and later inhibited by lead ions, although the most dramatic change was the appearance of early pro-arrhytmic, after-depolarizations at increasing concentrations of Pb2+ exposure. Heart contractions were also changed from their characteristic regular times and amplitudes. Our results indicated that heart functioning has to be thoroughly evaluated in lead poisoning, especially in patients with acute lead ion exposure. In addition, one of the methods to block acute cardiotoxicity from lead ions is complete removal, or the promotion of counteracting effects on the Cav1.2 channels. Since Cav1.2 channels are widely distributed in different cells and tissues, studies of lead ion toxicity on these channels in the heart can be extrapolated to other cells, tissues and organ types in which Cav1.2 channels play a critical physiological role. Alternative explanations for a direct effect of Pb2+ on Ca2+ channels might be 1− a direct effect of Pb2+ on other ion channels and transporters critical for CICR, such as the Ryanodine receptor type 2 channels from the SR, the Ca2+ pumps from the SR and the plasma membrane or the NCX transporter. Additionally, there could be indirect effects of Pb2+ on Ca2+ signaling pathways and redox systems, disrupting the calcium homeostasis. Though all these alternative mechanisms might play a role, the kinetics of the observed effects and independence of the cell systems argue in favor of Pb2+ acting directly through Cav1.2 channels. Exactly how lead ions interfere directly with Cav1.2 channels is not known, but it could be explained by fast binding kineticsof on and very slow kinetics of off reactions with Cav1.2 channels. Based on our results, we are continuing to develop in our laboratories additional experiments to further test the cardiotoxicity of lead ions.

References

Amado EM, Freire CA, Grassi MT, Souza MM (2012) Lead hampers gill cell volume regulation in marine crabs: stronger effect in a weak osmoregulator than in an osmoconformer. Aquat Toxicol 106-107:95–103. doi:10.1016/j.aquatox.2011.10.012

Ansari MA, Maayah ZH, Bakheet SA, El-Kadi AO, Korashy HM (2013) The role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway in cardiotoxicity of acute lead intoxication in vivo and in vitro rat model. Toxicology 306:40–49. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2013.01.024

Armant DR (2015) Intracellular Ca2+ signaling and preimplantation development. Adv Exp Med Biol 843:151–171. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2480-6_6

Atchison WD (2003) Effects of toxic environmental contaminants on voltage-gated calcium channel function: from past to present. J Bioenerg Biomembr 35:507–532

Audesirk G (1993) Electrophysiology of lead intoxication: effects on voltage-sensitive ion channels. Neurotoxicology 14:137–147

Babich O, Isaev D, Shirokov R (2005) Role of extracellular Ca2+ in gating of CaV1.2 channels. J Physiol 565:709–715. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086561

Babich O, Matveev V, Harris AL, Shirokov R (2007) Ca2+−dependent inactivation of CaV1.2 channels prevents Gd3+ block: does Ca2+ block the pore of inactivated channels? J Gen Physiol 129:477–483. doi:10.1085/jgp.200709734

Baranowska-Bosiacka I, Gutowska I, Rybicka M, Nowacki P, Chlubek D (2012) Neurotoxicity of lead. Hypothetical molecular mechanisms of synaptic function disorders. Neurol Neurochir Pol 46:569–578

Baranowska-Bosiacka I et al (2016) Effects of perinatal exposure to lead (Pb) on purine receptor expression in the brain and gliosis in rats tolerant to morphine analgesia. Toxicology 339:19–33. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2015.10.003

Bartolommei G, Gramigni E, Tadini-Buoninsegni F, Santini G, Moncelli MR (2010) Confining the sodium pump in a phosphoenzyme form: the effect of lead(II) ions. Biophys J 99:2087–2096. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.050

Basha DC, Basha SS, Reddy GR (2012) Lead-induced cardiac and hematological alterations in aging Wistar male rats: alleviating effects of nutrient metal mixture. Biogerontology 13:359–368. doi:10.1007/s10522-012-9380-9

Bellinger D, Leviton A, Waternaux C, Needleman H, Rabinowitz M (1987) Longitudinal analyses of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development. N Engl J Med 316:1037–1043

Bernal J, Lee JH, Cribbs LL, Perez-Reyes E (1997) Full reversal of Pb++ block of L-type ca++ channels requires treatment with heavy metal antidotes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 282:172–180

Bhatnagar A (2006) Environmental cardiology: studying mechanistic links between pollution and heart disease. Circ Res 99:692–705. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000243586.99701.cf

Braga MF, Pereira EF, Mike A, Albuquerque EX (2004) Pb2+ via protein kinase C inhibits nicotinic cholinergic modulation of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 311:700–710. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.070466

Bressler J, K-a K, Chakraborti T, Goldstein G (1999) Molecular mechanisms of lead neurotoxicity. Neurochem Res 24:595–600

Bressler JP, Olivi L, Cheong JH, Kim Y, Bannona D (2004) Divalent metal transporter 1 in lead and cadmium transport. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1012:142–152

Busselberg D (1995) Calcium channels as target sites of heavy metals. Toxicol Lett 82-83:255–261

Busselberg D, Michael D, Platt B (1994a) Pb2+ reduces voltage- and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-activated calcium channel currents. Cell Mol Neurobiol 14:711–722

Busselberg D, Platt B, Michael D, Carpenter DO, Haas HL (1994b) Mammalian voltage-activated calcium channel currents are blocked by Pb2+, Zn2+, and Al3+. J Neurophysiol 71:1491–1497

Canfield RL, Henderson CR Jr, Cory-Slechta DA, Cox C, Jusko TA, Lanphear BP (2003) Intellectual impairment in children with blood lead concentrations below 10 μg per deciliter. N Engl J Med 348:1517–1526

Casas JS, Sordo J (2011) Lead: chemistry, analytical aspects. Environmental Impact and health effects. Elsevier , Amsterdam

Chandran L, Cataldo R (2010) Lead poisoning: basics and new developments. Pediatr Rev 31:399–405

Chen HH, Chan MH (2002) Developmental lead exposure differentially alters the susceptibility to chemoconvulsants in rats. Toxicology 173:249–257

Chen ZZ, Zhu L, Yao K, Wang XJ, Ding JN (2009) [Interaction between calcium and lead affects the toxicity to embryo of zebrafish (Danio rerio)] Huan jing ke xue= Huanjing kexue / [bian ji, Zhongguo ke xue yuan huan jing ke xue wei yuan hui "Huan jing ke xue" bian ji wei yuan hui] 30:1205-1209

Cheong JH, Bannon D, Olivi L, Kim Y, Bressler J (2004) Different mechanisms mediate uptake of lead in a rat astroglial cell line. Toxicol sci 77:334–340. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfh024

Chiu TY, Teng HC, Huang PC, Kao FJ, Yang DM (2009) Dominant role of Orai1 with STIM1 on the cytosolic entry and cytotoxicity of lead ions. Toxicol Sci 110:353–362. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp099

Cory-Slechta DA, Garcia-Osuna M, Greenamyre JT (1997) Lead-induced changes in NMDA receptor complex binding: correlations with learning accuracy and with sensitivity to learning impairments caused by MK-801 and NMDA administration. Behav Brain Res 85:161–174

Costa C, Torres H, Hartmann H, Dutra J, Ferreira G (2014) Chemical cardiomyopathies: functional consequences of the application of chloroquine to guinea-pig isolated hearts. AnFaMed 1:65–79

Dabyntseva RD, Ulianenko TV, Borisevich AN, Filonenko LP, Chuiko AL, Lozinskii MO, Kosterin SA (1995) Combined effect of Pb2+ and divalent mental complexes on superprecipation and ATPase activity of myometrial actomyosin. Ukr Biokhim Zh 67(1978):46–52

Dibb KM, Graham HK, Venetucci LA, Eisner DA, Trafford AW (2007) Analysis of cellular calcium fluxes in cardiac muscle to understand calcium homeostasis in the heart. Cell Calcium 42:503–512. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2007.04.002

Dietz K-J, Baier M, Krämer U (1999) Free radicals and reactive oxygen species as mediators of heavy metal toxicity in plants. In: Heavy metal stress in plants. Springer, Berlin, pp 73–97

Dzhura I, Wu Y, Colbran RJ, Balser JR, Anderson ME (2000) Calmodulin kinase determines calcium-dependent facilitation of L-type calcium channels. Nat Cell Biol 2:173–177. doi:10.1038/35004052

Ferreira G (1992) Registro y caracterizacion del movimiento de carga intramembrana en miocitos aislados de miocardio ventricular de cobayo. MSc Thesis PEDECIBA, Universidad de la República

Ferreira G, Artigas P, Pizarro G, Brum G (1997a) Butanedione monoxime promotes voltage-dependent inactivation of L-type calcium channels in heart effects on gating currents. J Mol Cell Cardiol 29:777–787

Ferreira G, Yi J, Ríos E, Shirokov R (1997b) Ion-dependent inactivation of barium current through L-type calcium channels. J Gen Physiol 109:449–461

Ferreira G, Takeshima H, Rios E, Gonzalez A 1998. High intracellular calcium affects L-type calcium channel gating. Biophys J 74:A101

Ferreira G, Yi J, Ríos E 1999.Fast and slow mechanisms of voltage dependent inactivation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. Biophys J 76:A340

Ferreira G, Reyes N, Pizarro G, Brum G, Rios E 2001. Correlation between surfaces of inactivation of ionic currents and charge availability in L-type Ca2+ channels. Biophys J 80:620A

Ferreira G, Rios E, Reyes N (2003) Two components of voltage-dependent inactivation in ca(v)1.2 channels revealed by its gating currents. Biophys J 84:3662–3678. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75096-6

Findeisen F, Minor DL Jr (2010) Structural basis for the differential effects of CaBP1 and calmodulin on ca(V)1.2 calcium-dependent inactivation. Structure (London, England : 1993) 18:1617–1631. doi:10.1016/j.str.2010.09.012

Fioresi M, Simoes MR, Furieri LB, Broseghini-Filho GB, Vescovi MV, Stefanon I, Vassallo DV (2014) Chronic lead exposure increases blood pressure and myocardial contractility in rats. PLoS ONE 9:e96900. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096900

Fox DA, Rubinstein SD, Hsu P (1991) Developmental lead exposure inhibits adult rat retinal, but not kidney, Na+,K(+)-ATPase. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 109:482–493

Fu X, Zeng A, Zheng W, Du Y (2014) Upregulation of zinc transporter 2 in the blood-CSF barrier following lead exposure. Exp Biol Med (Maywood, NJ) 239:202–212. doi:10.1177/1535370213509213

Garza A, Vega R, Soto E (2006) Cellular mechanisms of lead neurotoxicity. Med Sci Monit 12:RA57–RA65

Gavazzo P, Gazzoli A, Mazzolini M, Marchetti C (2001) Lead inhibition of NMDA channels in native and recombinant receptors. Neuroreport 12:3121–3125

Gedeon Y, Ramesh GT, Wellman PJ, Jadhav AL (2001) Changes in mesocorticolimbic dopamine and D1/D2 receptor levels after low level lead exposure: a time course study. Toxicol Lett 123:217–226

Gidlow DA (2015) Lead toxicity. Occup Med (Oxford, England) 65:348–356. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqv018

Goasdoue K, Miller SM, Colditz PB, Bjorkman ST (2016) Review: the blood-brain barrier; protecting the developing fetal brain. Placenta. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2016.12.005

Goering PL (1993) Lead-protein interactions as a basis for lead toxicity. Neurotoxicology 14:45–60

Gorkhali R, Huang K, Kirberger M, Yang JJ (2016) Defining potential roles of Pb(2+) in neurotoxicity from a calciomics approach. Metallomics 8:563–578. doi:10.1039/c6mt00038j

Gravot A, Lieutaud A, Verret F, Auroy P, Vavasseur A, Richaud P (2004) AtHMA3, a plant P1B-ATPase, functions as a cd/Pb transporter in yeas. FEBS Lett 561:22–28. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(04)00072-9

Gu Y, Wang L, Xiao C, Guo F, Ruan DY (2005) Effects of lead on voltage-gated sodium channels in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. Neuroscience 133:679–690. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.039

Guilarte TR (1997) Pb2+ inhibits NMDA receptor function at high and low affinity sites: developmental and regional brain expression. Neurotoxicology 18:43–51

Habermann E, Crowell K, Janicki P (1983) Lead and other metals can substitute for Ca2+ in calmodulin. Arch Toxicol 54:61–70

Halling DB, Aracena-Parks P, Hamilton SL (2005) Regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by calmodulin. Sci STKE 2005:re15 doi:10.1126/stke.3152005re15

Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ (1981) Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Archiv 391:85–100

Haynes WM (2016) CRC handbook of chemistry and physics, 97th edn. CRCress, Boca Raton

Heavner JE (2002) Cardiac toxicity of local anesthetics in the intact isolated heart model: a review. Reg Anesth Pain Med 27:545–555

Hering S, Berjukow S, Sokolov S, Marksteiner R, Weiss RG, Kraus R, Timin EN (2000) Molecular determinants of inactivation in voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. J Physiol 528(Pt 2):237–249

Hess P, Lansman JB, Tsien RW (1986) Calcium channel selectivity for divalent and monovalent cations. Voltage and concentration dependence of single channel current in ventricular heart cells. J Gen Physiol 88:293–319

Housecroft CE, Sharpe AG (2012) Inorganic chemistry. Pearson, Harlow

Jang HO et al (2008) The effect of lead on calcium release activated calcium influx in primary cultures of human osteoblast-like cells. Arch Pharm Res 31:188–194