Abstract

This article explores the use of critical reflection to facilitate the construction of knowledge resulting from participation in e-service-learning courses. Such an instructional approach integrates an interdisciplinary curricular framework with site-specific service-learning opportunities resulting in an environment richer and more accessible through the use of technology. By facilitating the reflection process through this combination of service learning pedagogy and an online course format, students are empowered to both assess individual learning goals as well as collaborate with others to make meaning of their individual service-learning experience. Results from this study indicate that students felt reflection was essential to learning through gaining multiple perspectives and being introduced to a diversity of ideas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Creating and encouraging engagement in opportunities for dialogue, discourse, and inquiry are critical to facilitating students’ successful participation in e-service-learning courses. Within such a context, students’ and teachers’ engagement with curricula, learning environments, and technologies combine to ignite uniquely collaborative experiences. These experiences are essential to constructing new areas of knowledge that are representative of individualized meaning making as well as collective problem solving. It is through such processes that students develop capacities for the critical reflection and inquiry essential to learning and knowing: about themselves, the academic disciplines with which they are engaged, and societal challenges. In this study, service learning is situated in individual placements with nonprofit organizations. An interdisciplinary curricular framework is integrated with a range of instructional delivery media to provide a context in which students interpret and analyze their experiences at community service sites. When such opportunities are examined through broad multi-disciplinary lenses, reflective learning becomes individualized, spontaneous, and personally meaningful. The purpose of this study was to explore students’ perceptions of reflective learning in e-service-learning courses. How students learned through reflection, specifically whether they connected the course work to their service-learning experience, and if so, how they did this in an online environment was the focus.

Reflection in an online environment

Reflection is key to revealing the developmental opportunities in experience (Dewey 1933; Hatcher and Bringle 1997). Reflective inquiry has been conceptualized as the fundamental process through which human beings gain knowledge from their experiences (Fenwick 2001; Illeris 2007). Specifically structured reflection activities are critical for students to learn from experiences (Boud et al. 1985; Eyler et al. 1996; Guthrie and Bertrand Jones 2012).

In order for meaningful reflective inquiry to occur, secure intellectual and emotional spaces within virtual academic environments must be created; the skillful combination of pedagogical approaches as implemented through the use of technology is particularly important to promoting a high level of connectedness among course participants in online classrooms (Herner-Panode et al. 2011). Evolving learning is nurtured by promoting activities which facilitate a continuous process of structured reflection that enables transformation on cognitive and emotional levels. In this way, academic access is strengthened both via the use of technologies, as well as through the implementation of inclusive curricula that combine structured coursework with experiential learning opportunities through service learning.

Siemens (2009) and Williams et al. (2011) suggest that the interaction between multiple curricular variables enables spontaneous and unpredictable awareness, and as such, results in emergent learning. A “pluralistic learning ecology” (Williams et al. 2011, p. 44) consists of both structured experiences as well as opportunities to incorporate individual reflection. This ecology results in collective synergies that have the capacity to generate spontaneous meaning; reinforcing that reflective inquiry and practice are necessary for individuals, as well as learning communities, to acquire learning in a rapidly changing world (Kircher 2004).

Relationship of reflection to e-service-learning pedagogy

Many researchers and educators have identified critical inquiry, engaged dialogue, and reflective practice as essential to furthering substantive learning in experiential settings (Boud et al. 1985; Boyer et al. 2006; Kolb and Kolb 2005; Marsick and Mezirow 2002; Taylor 2000), such as e-service-learning. Such processes form the foundation for future decision-making and behaviors (Daudelin 1996). Knowledge resulting from reflective learning contributes to transferrable skills that include “…a process of critical examination that involves challenging assumptions, testing the logic of conclusions, considering multiple perspectives—not merely identifying facts and feelings…” (Clayton et al. 2005, p. 14). The role of reflection is particularly important because it enables informed experimentation to base the quality of critical analysis essential to developing personal awareness, academic understanding, and professional practice (Schön 1983; McGuire et al. 2009). Reflection occurring as a result of service learning has the potential to influence cognitive, affective, and moral development (Jones and Abes 2004; Strain 2005; Wang and Rodgers 2006); without such reflection, learning is not sustainable in a way to guarantee its future transference and application (Chickering 2008).

Educators acknowledge that learners derive meaning from experiences that occur through direct involvement and action. Such learning is possible only to the extent that conscious reflection about the experience occurs (Argyris 2003; Brockbank and McGill 1998; Davis and Sumara 2011; Kolb 1984). Interaction (with others, environments, cultures, and technologies) is a critical component of the learning-teaching relationship in order for experience to be analyzed as purposeful and for meaning to extend beyond the individual (Bell 2011; Eyler et al. 1996; Illeris 2007; Olsson et al. 2008; Strait and Sauer 2004). Kukulska-Hulme (2010) describes this process of learning from experience as the development of “context awareness” (p. 4) that evolves as a result of increased consciousness of one’s environment.

A variety of pedagogical approaches enables outreach to students with a wide range of cognitive processes. The capacity for reflection-in-action is best cultivated through participation in structured opportunities for authentic and purposeful learning which is both cyclical and progressive (Fiddler and Marienau 2008). For example, individual reflections facilitated through engagement in ongoing asynchronous discussions that utilize specific guiding questions emphasize the importance of integrating perceptions of experiences with meaningful academic learning. The facilitation of online discussions is particularly effective in encouraging reflective practice; when conscientiously created such activities promote a thoughtful exchange of ideas among learning peers. Such conversations generally center around specific topics identified in the review of course materials discussed within the context of experiences students have during participation at their community service experiences.

The process of challenging students’ approaches to self reflection (as demonstrated, for example, through ongoing contributions to web-based journals and asynchronous threaded discussions, or as expressed in reflective essays and position papers) encourages them to critically think. Knowledge, then, results from the culmination of navigating the curricula, balancing collaborative and individual learning opportunities, internalizing goals and outcomes, and integrating experiences to transform learning in ways that are relevant and valuable (Kolb 1984). The development of critical thinking and meta-cognitive skills are particularly important outcomes of students’ participation in a reflective process situated in experience (Ash et al. 2005) to the extent that metacognition captures the essential features of self-appraisal and self-management.

A reflective process that facilitates both active and passive inquiry (for example, questioning occurring during the experience as opposed to questioning afterwards) enables the depth and breadth required for learning to extend beyond personal awareness to impact individual cognitive change (Doyle 2007). Reflective learning is both spontaneous and purposeful, the outcome of a synergy which includes the contributions of many interactions.

Community of inquiry

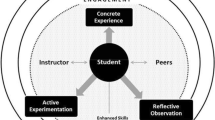

Garrison et al. (2000) and Garrison and Hanuka (2004) discuss a community of inquiry model that provides the framework for realizing reflective, experientially based pedagogies as implemented in virtual learning environments. Attention to combined teaching, social, and cognitive elements enables an instructional presence that reinforces the reflective learning critical to achievement within as e-service-learning framework. Through methods such as written journals and reflection papers, text-based exchanges, peer-to-peer collaboration, and team/small group presentations reflective learning is achieved (Garrison et al. 2000; Garrison and Hanuka 2004; Ginns and Ellis 2007; Guthrie and Bertrand Jones 2012; Guthrie and McCracken 2010). By uniting these key aspects of the instructional process, teachers, students, and placement personnel form meaningful partnerships that facilitate ongoing dialogue, foster developing insight, generate both individual and collective learning outcomes, and contribute to strengthening active and collaborative communities. Furthermore, partnerships are created between the community service organizations and institutions, thus sustaining the capacity to extend the potential for community impact through engagement with future students.

The use of technologies is critical in the construction of student-instructor relationships in order to effectively facilitate the collective work of e-service-learning as well as assist students in realizing specific learning goals. It is essential to think beyond merely integrating technologies to revise the ways in which applications can transform instructional goals and learning outcomes (Garrison and Hanuka 2004). For purposes of this study, such goals included cultivating and facilitating productive and participative learning communities, as well as promoting ongoing individual and collective inquiry through reflection and engagement (King and Kitchener 1994). Technologies utilized in the instruction of the studied course are commonly used in educational settings; their use reinforces significant learning and facilitates personal and academic development in service-learning courses (Barab et al. 2001). Educational technologies were selected based on their capacities to facilitate interaction, communication, and collaboration in order to generate shared learning goals, solve common problems, and address the concerns and competencies of all stakeholders. A secure web-based environment formed through a learning management system enabled the use of a range of technologies to support collaborative learning (Kiely et al. 2004). Continuous communications and interactions were facilitated in conjunction with the integration of asynchronous discussion boards, blogs, and email as well as synchronous chat, and audio and video conferencing applications, or facilitated through cloud computing platforms that enabled critical interactions. Depending upon the nature and focus of the students’ learning goals, various online social networking services were also integrated into their experiences.

Research design

The purpose of this study was to explore students’ perceptions of reflective learning in e-service-learning courses. Approval for the use of human subjects was reviewed and granted by the institution attended by participants included in this study. In exploring e-service-learning pedagogy, which is contextual, a singular case study on how students make meaning through reflection is appropriate. Stake (2005) specifies that an “intrinsic case study” (p. 445) is undertaken because a better understanding of a particular case is the goal. An “instrumental case study” is a particular case that may provide insight into a broad issue (Stake 2005, p. 445). The design of this case study takes both intrinsic and instrumental types of case studies into account.

Due to the exploratory nature of the study, a mixed approach to the research design that combined qualitative and quantitative methods enabled the exploration of possible learning and potential impact. A brief web-based survey was initially distributed where respondents could agree to participate in subsequent interactive interviews. The approach taken in this study enabled the exploration of the phenomenon of experiential learning through service learning and reflection on that learning as guided by current qualitative methods, emphasizing that all learning is actualized through interaction, discourse, conversation, and narratives (Denzin and Lincoln 2005).

The online survey collected demographic information, initial reactions, and invited participation in the interview segment of the study. Collecting information through a survey and subsequently interviewing student respondents provided insight to the phenomenon of learning to the extent that participants shared their perceptions of their lived world (Kvale 1996). This data collection led to the articulation of specific knowledge about personal learning, which enhanced the understanding of one specific e-service-learning course and reflective pedagogies used in that course. The interactive interview segment enabled descriptive and interpretive analysis related individual and collective learning made possible through participation in reflective inquiry.

The e-service-learning course each student took in this study examines community engagement from a positive social action framework, exploring the means by which different leadership styles enact positive, sustainable change within organizations, neighborhoods, and larger communities. Students identify and develop community service projects that result in specific outcomes planned in collaboration with their onsite supervisors. Course requirements include the completion of individual action plans, 60 h of community service, participation in structured discussions, reflection journals, and reflective essays connecting individual community service with course readings, and concludes with final culminating papers. Upon completion of this course students gain a general understanding of service learning through participation in an ongoing reflective learning process; development of core personal values; recognition of various historical social change leaders; and, creation of an ethical framework as applied in action to civic engagement and leadership issues.

Participants

Potential participants were contacted by gaining access through the institution’s academic department through which the e-service-learning courses were offered. Enrollment lists from three academic semesters provided contact information related to potential participants. Students enrolled throughout nine sections of one specific e-service-learning course provided the context for this study. At the time of the request, 283 students were enrolled in the nine service-learning sections over three semesters. In the summer of 2012, 74 students were contacted; in the fall of 2012, 111 students were contacted; and, in spring 2013, 98 students were contacted. Once a list of possible participants was verified, each individual was contacted via e-mail with a link to the anonymous online survey. Of the 283 students contacted, 192 completed the survey for a 68 % return rate. Of the 192 students that completed the survey, 80 students or 42 % provided individual contact information with their consent to be interviewed; of this number, 44 students, 55 % were actually interviewed. Table 1 provides participant demographics.

Participants in this study were enrolled a wide range of academic disciplines. Business, including Management and Accounting majors, were the most represented with 82 students; 33 students were studying Computer Science, 22 students were studying Criminal Justice and Legal Studies; 14 students were enrolled as Communications majors; Political Science, History, and Psychology were each represented by 7 students; and Global Studies, Math, Biology and Chemistry each had 5 major reporting. One hundred sixty-four students reported that they were motivated to enroll in one of the service-learning online courses because it fulfilled a general education requirement; 21 students responded that it fulfilled a requirement for their major; and, 7 reported participating out of personal interest.

Survey design

The brief seven-question survey was created to collect demographic information as well as initial reactions to reflective pedagogy. General demographic information collected included age, gender, major, year in school, ethnicity, and frequency of enrollment in online courses. Open ended questions such as, “how do you define reflection?”; “how do you best make meaning of the experiences you have?”; “what forms of reflection are required for the service-learning course you are currently enrolled in?”; and, “what other types of reflection would be useful for you to make meaning of your experiences?” were asked. The final survey question invited students to participate in a follow up interview conducted via telephone. The qualitative nature of the survey provided opportunities for the expression of perceptions and reactions through narratives.

Interview plan and process

Forty-four students participated in an interview either via telephone or an online audio platform between May and June 2013. The interviews typically were 20–40 min in length and were conducted by the lead researcher. The goal of this semi-structured interview was to collect detailed descriptions of the students’ experiences, thoughts, and feelings related to the service-learning course they participated, with a specific focus on the value and role of reflective inquiry on learning outcomes. The survey answers provided a starting point for the interview. The first interview questions were asking the open ended survey questions again. Additional primary questions asked during the interview included, “What were the top three things you learned from participating in this course?”; “In the online service-learning course you were enrolled in, what was the most meaningful way you connected your service to the course material?”; “Was there a specific moment in the course, either during discussion board responses, your service experience, or journal writing that you feel was influential in your learning?” The interview instrument gathered direct quotations, a basic source of raw data in a qualitative study in as much as such data reveal respondents’ emotional interpretation and reactions as they organize their experiences with respect to learning, reflection, and basic perceptions (Patton 1980).

In implementing the semi-structured interview, two types of questions were used: primary questions and probing questions identified as appropriate for inclusion in the semi-structured interview (Rubin and Rubin 1995). Primary questions were prepared for the interview ahead of time and were consistently asked of all participants. Probing questions were used during the interviews to clarify participants’ initial responses, giving them opportunities to expound on ideas that evolved from reflective inquiry.

Data analysis

Description, analysis, and interpretation were the three ways of organizing, reporting, and analyzing qualitative data in this study (Wolcott 1994). Researching themes and foci prior to data collection allowed the authors to acquire additional knowledge related to constructing a framework for interpretation. This research was initially accomplished through a review of literature and reflection on personal experiences as both students participating in and faculty members teaching in online instructional environments. Initial codes were created and included ideas found in previous studies on reflection.

In the analysis of data, transcripts from the interviews were read and reviewed multiple times by two researchers; data that aligned with initial codes were highlighted. Phrases and words were used to determine codes for each participant. Emerging themes were also identified when the same ideas surfaced in three or more student transcriptions. Once emerging themes were studied, relationships among those themes were examined. Moreover, a researcher external to the data collection process was solicited to further review the data in order to obtain an additional perspective related to the identification of relevant themes. This combination of analyses related to theme differentiation found in both the external and primary researchers’ reviews are presented for discussion.

Reflection as essential to learning

Of the 192 students who completed the survey, 154 responded that reflection was essential to achieving a significant level of learning. Regardless of the technology utilized to facilitate inquiry and awareness (for example, through writing reflective essays and journals, or participating with peers, instructors, or colleagues in discussions), reflection was described as essential to their learning process. Such directed reflection had the effect of connecting the class to the readings and course materials, as well as students to each other, and was found to have contributed to positive learning outcomes.

While participants’ majors and areas of studies varied, students related to one another’s experiences through connecting the instructional elements that guided a reflective process. Participation in the course was reported as beneficial to online students on several levels. For example, of the 44 students interviewed, 35 students (81 %) discussed that reflection occurring as a result of participation in this course was essential to their learning. The curriculum combined with a guided instructional approach facilitated ongoing reflection and critical inquiry that enabled the diverse student population to achieve a synergy that transcended disciplinary boundaries. One student explained, “Being able to reflect both personally through the journal and with others in the discussion board was critical to my learning. It pushed me to think of things differently.” Another student reported, “The amount of reflection in this class was incredible. At first I was not sure if I would like it, but it ended up being what I learned the most from.” A third student explained her/his experience of engagement due to the integration of reflection related to the learning process,

Being able to learn from a classmate’s take on my experience was cool. The discussion board helped bring people studying different things together and relate to each other through our experiences and course topics. I think because we were trying to explain our own experiences doing our community service it made us more engaged… I can’t think of that happening in any other online classes I have taken.

While students integrated their experiences through discipline-specific lenses, the data collected indicated the primacy of reflection to their learning processes.

Additional feedback received from students noted the ways in which key topics sequenced in the curricula relate to current world problems and situations. Actual topics covered include community engagement, lifelong learning, and the ways one can make positive change. While the focus of reflection often directly relates to current events, it also speaks to students on a personal level. Reflection on the ways the course topics relate to each student’s individual experience with service enables them to build the confidence to take the course theory and put it into practice in their communities. Reflection becomes the means to achieve connectedness to the course material, classmates, and instructor.

Benefit of multiple perspectives

During the interviews, respondents repeatedly reported the benefit of multiple perspectives as having a positive effect on overall learning, especially when critically thinking about course material. Of the 44 students interviewed, 22 students (50 %) mentioned that multiple perspectives not only reinforced their learning experiences, but also were often needed to solve major issues. On two specific occasions in the studied course, students were given a case study regarding a social issue in our society. Their charge was to provide next steps in moving towards solving this social issue. Online discussions provided a particularly effective environment for students to explore the interpretations and analyses of those social issues with a range of experiences, placement settings, and academic disciplines in mind. The structured questions characteristic of guided discussions focused around course materials, and in this way reinforced learning outcomes achieved in the service-learning courses. This integrative process required students to incorporate personal experiences at community service sites with theoretical concepts to form both individual and collective analyses.

Students enrolled specifically in the online service-learning classes frequently mentioned the need for and benefit of multiple perspectives in resolving major social issues. One student emphasized, “I think of large societal problems like health care, homelessness, or global warming. These are issues that affect all of us. We need multiple perspectives, people with different expertise to solve them.” A second student commented, “This class made me realize how we need many different strategies to solve issues that plague our communities. I would not have gotten this in my major only classes.” Five students referred to an engaging online discussion a group of students had in one class around ending homelessness. One student noted, “I am a numbers person, so I was thinking about money only. Others were thinking about services and policy. It was interesting.” The student who initiated the conversation said,

I was doing my service in a homeless shelter, so I threw the question of how we should end homelessness out there. It was incredible to see how people from different disciplines would solve it. I have never been so engaged in an online discussion. I realized…we need many people with many different backgrounds to solve such a large problem in our society.

Another student referred to the same conversation,

A guy in our class was doing his service at a homeless shelter and he was wondering how we should end homelessness. The conversation was amazing and it made me realize that we need to tackle major problems that affect many from different angles. Not just one of group of people can solve it.

Whether focused on a specific conversation or a general observation, students felt guided opportunities for reflection provided them rich opportunities to discuss multiple perspectives on experiences, problems, and goals. These varying perspectives and the resulting reflection assisted in opening conversations of ways collaboration can be powerful when used to benefit society as a whole.

Appreciation of diverse ideas

Diversity of ideas was demonstrated throughout the service-learning courses, students consistently remarking that they valued opportunities to consider ideas in new ways. While the benefit of multiple perspectives were discussed around solving social issues and the critical thinking that occurs, appreciation of diverse ideas focused more on personal processing and placing self in a specific academic discipline. Participating in these e-service-learning courses with students from various geographical locations, backgrounds, experiences, and academic interests provided a positive environment in which to discuss diverse ideas. Twenty (45 %) of the students interviewed discussed a variety of ideas and the opportunity provided by online forum to discuss these diverse ideas were appreciated. For example, one student commented, “I really appreciated the diversity of ideas this class brought. This last year I have only been in classes with people in my major. It was good to be with others who have different ideas.” As this student stated, having a course with students from other majors enabled new perspectives to emerge as a result of both previous and current experiences. Another student said, “I liked how people were from different majors in this class. It made the ideas presented in our discussions very different.” Yet another student said, “Since there were people from all colleges in this online class, we heard a variety of ideas on every topic.”

As this data indicates, integrating students from a variety of academic disciplines provided a forum for the discussion diverse topics and ideas; such discussions not only enabled an understanding of the service they were providing, they also constructed emerging ideas by both individuals and the collective. Students indicated having an online course which guides reflection of individual experiences was a positive experience that contributed to their overall learning. Actually applying the diversity of students’ experiences to the course material brought richness to the reflection and enhanced the overall application of material. One student said, “Integrating everyone’s diverse experiences and applying it to material in the class was great. I definitely learned from it.” Another student said, “I never thought I would learn so much in an online class. While I learned from our course readings, I learned more from the interaction of our classmates… The range of ideas opened my eyes.”

As these students attest, having the opportunity discuss diverse ideas through reflection in interdisciplinary courses was a positive experience for many participants. The combination of service-learning opportunities and assignments that facilitate reflection when conducted with an interdisciplinary student population in an online classroom provides a rich environment for learning. It also enables emergent ideas related to student self analyses and instructional direction to be constructed.

Discussion and implications

The results of this study suggest that e-service-learning courses delivered to interdisciplinary students provide rich opportunities for reflective and collaborative learning. This particular academic blend holds promise related to generating learning strategies, technology applications, and teaching approaches. Each component acts in concert with the next to exact potential based on individual and collective goals, needs, and learning styles. However, the emergent qualities of this instructional approach can be fleeting; such innovation and creativity are virtually impossible to replicate since their evolution is dependent upon context.

Reflective process as key to learning

As illustrated by the results of this study, instructional processes that facilitate reflection upon individual and collective experiences enable depth and breadth to learning. Seaman (2008), however, cautions that such reflection can be a limiting activity because it conforms to institutional standards, such as a specific curriculum; in this context reflection—and the subsequent learning—has the potential to be a prescriptive exercise. There is also a potential for service learning to be negatively internalized in such a way that obsolete attitudes, values, and biases are reinforced. By facilitating an environment that fosters continuous critical reflection without judgment or bias, instructors assist students to develop self-knowledge resulting from experiences that span an intellectual continuum.

Promise of experiential learning

Reflection must be a guided process in order for its results to be consistent with institutional goals, viewed as academically viable as well as individually meaningful (Boud et al. 1985; Seaman 2008). When introduced into teaching environments in which it is not practiced skillfully or fully understood, there is the potential for misuse (Doyle 2007). As an intervention, both Doyle (2007) and Brookfield (2011) recommend an instructional approach which change is the norm to cultivate an environment rich in critical thought and being.

Supporting students with a wide range of competencies as they develop essential skills to generate and continue ongoing engagement requires ongoing attention. Instructors facilitating virtual classrooms must invest to understand students’ developmental levels related to communication proficiency in a highly text-based learning environment, the use of specific technical tools, and the ability to integrate a variety of relationships into a multi-dimensional educational experience. Understanding topics of social responsibility and civic engagement are challenging in that these are complex and highly personal endeavors in meaning making. Guiding students on these reflective journeys can be challenging when interaction is not instantaneous.

Interdisciplinarity as a viable instructional framework

An interdisciplinary approach to instruction is an inclusive method that attempts to ensure representation across academic disciplines; such approaches reinforce both individualization and collaboration. Such interdisciplinarity is integrated throughout an online curriculum when the participant population represents a range of disciplines. A final assessment of teaching methods is refined only after the final enrollments are set and class composition is known. Once discipline affiliations are clear, instructors can modify approaches based on population traits and demographic information. As indicated in the study, students generally remarked related to the value of learning about other’s experiences from a range of disciplinary focuses. However, an argument can be made for the benefits of discipline-specific focused learning experiences; it is true those participating in similar experiences will derive learning from shared resources, goals, needs, and outcomes.

The importance of intentionally constructing the learning environment

The ongoing engagement, examination, analyses, and review of students’ participation required when utilizing reflective pedagogies are most effectively managed when class size is limited. However, growing enrollments pose challenges to managing the relational dynamics inherent in the facilitation of intimate course discussions. While different formats and technologies are useful in creating highly interactive discussions, it is sometimes at the sacrifice of connectedness with the entire course, which, then impacts students’ potential for collective learning. For example, in large classes, students seem reluctant to become vulnerable by sharing emotional stories with such large numbers of people.

Conclusion

This case study suggests that within the context of e-service-learning courses, technologies, pedagogies, and learning environments, there is relevance and application of reflective learning and teaching. This approach to teaching and learning enables both individual self-direction and collective knowledge development; as such, this instructional combination can be assessed as effectively interactive. The overall teaching approach serves multiple pedagogical functions focusing on the integration of experience and reflection as the means to further both academic growth and skill development. E-service-learning courses enable increasingly personal learning through customizable technologies, individual experiences, and collective spaces that combine to produce emergent meaning: a new direction for teaching, learning, and reflecting. While this study focused on a specific case, more institutions should explore e-service-learning courses as viable options to engage students in their community and assist them in making meaning from these experiences.

References

Argyris, C. (2003). A life full of learning. Organization Studies, 24(7), 1178–1192.

Ash, S., Atkinson, M. P., & Clayton, P. H. (2005). Integrating reflection and assessment to capture and improve student learning. Journal of Community Service Learning, 11, 49–60.

Barab, S., Thomas, M., & Merrill, H. (2001). Online learning: From information dissemination to fostering collaboration. Michigan Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 12(1), 105–143.

Bell, F. (2011). Connectivism: Its place in theory-informed research and innovation in technology-enabled learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(3), 98–118.

Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Promoting reflection in learning: A model. In R. Keogh, D. Walker, & D. Boud (Eds.), Reflection: Turning experience into learning (pp. 19–40). New York: Kogan Page.

Boyer, N., Maher, P., & Kirkman, S. (2006). Transformative learning in online settings: The use of self-direction, metacognition, and collaborative learning. The Journal of Transformative Education, 4(4), 335–361.

Brockbank, A., & McGill, I. (1998). Facilitating reflective learning in higher education. Buckingham: OUP.

Brookfield, S. (2011). The skillful teacher: Core practices of skillful teaching [pdf document]. Available from Jossey-Bass Faculty Development http://www.josseybass.com/WileyCDA/Section/id-302502.html

Chickering, A. W. (2008). Strengthening democracy and personal development through community engagement. New Directions in Adult and Continuing Education, 118, 87–95.

Clayton, P. H., Ash, S. L., Bullard, L. G., Bullock, B. P., Moses, M. G., Moore, A. C., et al. (2005). Adapting a core service-learning model for wide-ranging implementations: An institutional case study. Creative College Teaching, 2, 10–26.

Daudelin, M. W. (1996). Learning from experience through reflection. Organizational Dynamics, 24(3), 36–48.

Davis, B., & Sumara, D. (2011). Learning communities: Understanding the workplace as a complex system. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 92, 85–95.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston: D. C. Heath.

Doyle, M. (2007). A reflexive critique of learner-managed learning: An emerging curriculum model for a foundation degree. Reflective Practice, 8(2), 193–207.

Eyler, J., Giles, D. E., & Schmeide, A. (1996). A practitioner’s guide to reflection in service- learning: Student voices and reflections. A Technical Assistance Project funded by the Corporation for National Service. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University.

Fenwick, T. (2001). Experiential learning: A theoretical critique from five perspectives. Columbus: Ohio State University.

Fiddler, M., & Marienau, C. (2008). Developing habits of reflection for meaningful learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 118, 75–85. doi:10.1002/ace.297.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. Internet and Higher Education, 2(3), 87–105.

Garrison, D. R., & Hanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet and Higher Education, 7(2), 95–105.

Ginns, P., & Ellis, R. (2007). Quality in blended learning: Exploring the relationships between on-line and face-to-face teaching and learning. Internet and Higher Education, 10(1), 53–64.

Guthrie, K. L., Bertrand Jones, T. (2012). Teaching and learning: Using experiential learning and reflection for leadership education. In: Guthrie, K. L., Osteen, L. (Eds.), Developing students’ leadership capacity (New Directions for Student Services, No. 140, pp. 53–64). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Guthrie, K. L., & McCracken, H. (2010). Promoting reflective discourse through connectivity: Conversations around service-learning experiences. In L. Shedlesky & J. Aitken (Eds.), Cases on online discussion and interaction: Experiences and outcome (pp. 66–87). Hersey, PA: IGI Global Publishers.

Hatcher, J. A., & Bringle, R. G. (1997). Reflection: Bridging the gap between service and learning. College Teaching, 45(4), 153–158.

Herner-Panode, L., Lee, H., & Baek, E. (2011). Reflective e-learning pedagogy. In Information Resources Management Association (Ed.), Instructional design: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications. IGI-Global: Hershey, PA.

Illeris, K. (2007). What do we actually mean by experiential learning? Human Resource Development Review, 6(1), 84–95.

Jones, S. R., & Abes, E. S. (2004). Enduring influences of service-learning on college students’ identity development. Journal of College Student Development, 45(2), 149–166.

Kiely, R., Sandmann, L., & Truluck, J. (2004). Adult learning theory and the pursuit of adult degrees. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 109, 17–30.

King, P. M., & Kitchener, K. S. (1994). Developing reflective judgment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Kircher, P. (2004). Design, development, and implementation of electronic learning environments for collaborative learning. ETR&D, 52(3), 39–46.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 4(2), 193–212.

Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2010). Learning cultures on the move: Where are we heading? Educational Technology and Society, 13(4), 4–14.

Kvale, S. (1996). InterViews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Marsick, V., & Mezirow, J. (2002). New work on transformative learning. The Teachers College Record. New York: Teachers College Record.

McGuire, L., Lay, K., & Peters, J. (2009). Pedagogy of reflective writing in professional education. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 9(1), 93–107.

Olsson, A., Bjöörn, U., & Jönson, G. (2008). Experiential learning in retrospect: A future organizational challenge? Journal of Workplace Learning, 20(6), 431–442.

Patton, M. Q. (1980). Qualitative evaluation methods. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (1995). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Seaman, J. (2008). Experience, reflect, critique: The end of the “learning cycles” era. Journal of Experiential Education, 31(1), 3–18.

Siemens, G. (2009). Complexity, chaos, and emergence. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/View?docid=anw8wkk6fjc_15cfmrctf8&pli=1

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 443–466). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Strain, C. R. (2005). Pedagogy and practice: Service-learning and students’ moral development. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 103, 61–72.

Strait, J. & Sauer, T. (2004). Constructing experiential learning for online courses: The birth of e-Service. EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 27(1). Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/EDUCAUSE+Quarterly/EDUCAUSEQuarterlyMagazineVolum/ConstructingExperientialLearni/157274

Taylor, E. (2000). Analyzing research in transformative learning theory. In J. Mezirow (Ed.), Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress (pp. 285–328). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wang, Y., & Rodgers, R. (2006). Impact of service-learning and social justice education on college students’ cognitive development. NASPA Journal, 43(2), 316–337.

Williams, R., Karousou, R., & Mackness, J. (2011). Emergent learning and learning ecologies in Web 2.0. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(3), 39–50.

Wolcott, H. F. (1994). Transforming qualitative data: Description, analysis and interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guthrie, K.L., McCracken, H. Reflection: the importance of making meaning in e-service-learning courses. J Comput High Educ 26, 238–252 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-014-9087-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-014-9087-9