Abstract

A 70-year-old woman was referred to our hospital because of slight elevation of soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) and accumulation of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in S8 of the liver on positron emission tomography. The mass was strongly suspected to be malignant because of contrast enhancement and enlargement in size of the mass, and suspicion of portal vein invasion. Hepatic S8 subsegmentectomy was performed for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the resected specimen showed small lymphocytes with no atypia and no formation of lymphoid follicles. Immunostaining showed CD3-positive cells in the interfollicular region and CD20-positive cells in the lymphoid follicles. Both CD10 and BCL-2 were negative in the follicular germinal center. CD138-positive plasma cells were observed and there was no light chain restriction. Based on polyclonal growth pattern of lymphocytes in the lymphoid follicles and interfollicular region, she was diagnosed with hepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH).

Review of the English literature of hepatic RLH which referred to imaging findings yielded 23 cases, including this case. As a result, we suggest that liver biopsy should be performed for definitive diagnosis, when hepatic RLH is suspected by imaging findings and backgrounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH), also known as pseudolymphoma, presents lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers and polyclonal reactive proliferation with no atypia in the lymphocytes [1, 2]. No typical imaging of hepatic RLH has been reported. Therefore, preoperative diagnosis of hepatic RLH is difficult and hepatic RLH is mostly diagnosed postoperatively. In this report, we present a rare case of hepatic RLH with characteristic imaging findings.

Case report

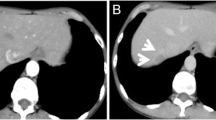

A 70-year-old woman had been treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy for intra-abdominal follicular lymphoma 12 years before, and had been remained in remission. She was followed up by blood tests and positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET-CT). She was referred to our hospital because of slight elevation of soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) and accumulation of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in S8 of the liver in PET-CT (Fig. 1a). Laboratory data, including lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, total protein, albumin, and globulin, were within normal range. Hepatitis B virus DNA and hepatitis C virus RNA were negative. Antinuclear antibody and anti-mitochondrial antibody were negative. Tumor markers, including α fetoprotein, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohydrate antigen 19–9, were within normal range except for slight elevation of s-IL-2R: 592 U/ mL. Abdominal ultrasonography (US) showed a hypoechoic mass, 16 mm in size, in the S8 of the liver, which was well defined and homogeneous (Fig. 1b). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CE-CT) showed a pale ring-shaped contrast enhancement in the early phase and washed out in the late phase (Fig. 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed hypointense on T1-weighted image and hyperintense on T2-weighted image, and diffusion restriction along the mass and surrounding the portal vein (Fig. 3). Contrast-enhanced MRI (CE-MRI) showed contrast enhancement in the early phase, washed out in the late phase, hypointense in the hepatocyte phase (Fig. 3). The background liver was normal on all imaging findings, and there was no evidence of fatty liver, hepatitis, or cirrhosis. Re-examined CE-CT after 3 months showed that the hepatic mass became well defined and slightly enlarged, and portal vein invasion was suspected (Fig. 4). The mass was strongly suspected to be malignant, such as the recurrence of follicular lymphoma, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Although the preoperative diagnosis was difficult because of the lack of typical findings on imaging, liver biopsy was not performed due to the risk of dissemination. Hepatic S8 subsegmentectomy was performed for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Macroscopically, multiple white nodules without capsules were observed within an area of 16 mm in diameter (Fig. 5). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the resected specimen showed small lymphocytes with no atypia and no formation of lymphoid follicles (Fig. 5). There was no hepatitis in the resected specimen. Immunostaining showed CD3-positive cells in the interfollicular region and CD20-positive cells in the lymphoid follicles. Both CD10 and BCL-2 were negative in the follicular germinal center. CD138-positive plasma cells were observed and there was no light chain restriction, because the κ/λ ratio was within normal range (Fig. 6). These results indicated polyclonal growth pattern of lymphocytes in the lymphoid follicles and interfollicular region. Portal vein invasion of the tumor was suspected on the preoperative imaging; however, pathological finding shows many lymphocytes around the portal vein and no direct invasion into the portal vein. Thus, she was finally diagnosed with hepatic RLH.

Immunostaining showed CD3-positive cells in the interfollicular region, CD20-positive cells in the lymphoid follicles. Both CD10 and BCL-2 were negative in the follicular germinal center. CD138-positive plasma cells were observed and there was no light chain restriction, because the κ/λ ratio was within normal range

Discussion

Hepatic RLH presents lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers and polyclonal reactive proliferation with no atypia in the lymphocytes [1, 2]. This disease is thought to be related to autoimmune disease, chronic hepatitis, and malignancies [2,3,4, 19]. To our knowledge, only 87 cases of hepatic RLH/ pseudolymphoma have been reported in the English literature on PubMed. No typical imaging finding of hepatic RLH has been reported. CE-CT and CE-MRI imaging show a variety of findings in each case. Therefore, preoperative diagnosis of hepatic RLH is difficult, and hepatic RLH is mostly diagnosed postoperatively.

Review of the English literature of hepatic RLH/pseudolymphoma which referred to imaging findings yielded 23 cases [1, 2, 5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], including this case (Table 1, Table 2). The average age was 60 years and most cases were females (96%) (Table 1). Hepatitis virus infection was present in 33% of them, and 67% were non-infected (Table 1). Elevation of hepatic enzymes were not seen in 87% of the patients (Table1), and hepatic tumor markers were not elevated in all cases (Table 1). The antinuclear antibody was positive in 8 cases, and 3 cases (Case 3, 20, 21) of them had no history of autoimmune disease (Table1). A history of autoimmune disease was observed in 8 cases and malignancy was observed in 6 patients (Table 1). It occurred a little more frequently in the right lobe of the liver (56%) (Table 2). The average size was 15 mm in diameter (Table 2). On imaging, US showed hypoechoic mass (100%). CE-CT and CE-MRI showed contrast enhancement in the early phase and relatively wash out in the late phase (95%). MRI showed hypointense on T1-weighted image (100%) and hyperintense on T2-weighted image (100%), and diffusion restriction (100%) (Table 2). Preoperative diagnoses included HCC (50%), metastatic liver tumor (13%), any malignant tumor (25%), intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (4%), RLH (4%), and hepatic adenoma (4%) (Table 2). Eighty-eight percentage of the cases underwent surgery (Table 2), other 12% (Case3, 16, 23) of the cases performed liver biopsy for diagnosis and did not receive hepatic resection (Table 2). In Case 3, percutaneous ethanol injection was performed [5]. In Case 16, radiofrequency ablation was performed [14]. Case 23 was followed up without treatment [21]. These cases has been followed up without recurrence and evidence of malignancy [5, 14, 21].

Hepatic RLH rather than HCC is suspected based on the patient’s background and imaging as follows. Hepatic RLH is mostly middle-aged women. Laboratory data show no elevation of hepatic enzymes or hepatic tumor markers. Autoantibodies, such as antinuclear antibodies, are frequently positive in hepatic RLH. Hepatic RLH is often associated with autoimmune diseases and malignancies [2,3,4, 19], and hepatitis virus infection is less common than HCC.

This case had undergone radiation chemotherapy for intra-abdominal follicular lymphoma 12 years ago and remained in remission. This time, only a hepatic mass was detected on systemic imaging examinations. We also suspected a recurrence of follicular lymphoma due to mild elevation of s-IL2R, but pathology of the resected liver specimen revealed hepatic RLH. The follicular lymphoma has been followed up without recurrence. It is unclear whether a history of lymphoma was associated with hepatic RLH in this case. Although the cause of hepatic RLH is not yet fully understood, an abnormal immune system due to autoimmune disease or malignancy may be involved in hepatic RLH [3, 19].

Contrast CT and MRI findings of hepatic RLH are similar to those of HCC, but hepatic RLH often shows a peripheral contrast effect (Table 2), which is considered to reflect lymphocytes around the portal vein [2] and is consistent with the findings of linear diffusion restriction along the portal vein on DWI [22]. In hepatic RLH, swelling of the portal vein area caused by lymphocytes may show diffusion restriction on MRI, so vascular invasion is often suspected as a finding of malignancy. However, this finding is characterized by linear diffusion limitation along the portal region [22]. Contrast-enhanced US (CE-US) can confirm the contrast enhancement overtime and shows very earlier contrast enhancement and washout than HCC [23], and thus, CE-US is useful for differentiating hepatic RLH from HCC. The timing of CE-CT phase imaging differs by facility, and it creates variety of contrast enhancement. Nevertheless, our data showed that the contrast enhancement was relatively washed out in many cases (95%). Therefore, for a hepatic mass with atypical imaging findings, contrast enhancement of CE-US, peripheral contrast effect of CE-CT/MRI, and diffusion limitation along the portal vein could be useful for the diagnosis of hepatic RLH.

If hepatic RLH is suspected by the patient’s background and imaging, liver biopsy is needed for definitive diagnosis of hepatic RLH. It has been reported that a sufficient amount of liver tissue can be obtained for the diagnosis of this disease by liver biopsy and that immunostaining can determine lymphocyte polyclonality [4]. There have been cases of hepatic RLH with background normal liver or autoimmune disease diagnosed by liver biopsy [4]. In those cases, a reduction in mass size was confirmed during follow-up period [4, 5, 14, 21].

In conclusion, a hepatic mass with atypical imaging findings and backgrounds, hepatic RLH should be considered as a differential diagnosis. Middle-aged women with autoimmune disease or malignancy, and even if not, measuring autoantibodies may help in the diagnosis. Diagnosis of hepatic RLH includes early contrast enhancement and relatively early washed out on CE-CT/US, peripheral contrast effect of CE-CT/MRI, and diffusion limitation along the portal vein on MRI may be useful imaging findings. We suggest that liver biopsy should be considered to avoid surgery in patients who do not have typical risk factors for HCC or other hepatic malignancy, but have characteristics for hepatic RLH as described above.

Abbreviations

- RLH:

-

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia

- PET-CT:

-

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- sIL-2R:

-

Soluble interleukin-2 receptor

- FDG:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose;

- US:

-

Ultrasonography

- CE-CT:

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CE-MRI:

-

Contrast-enhanced MRI

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- CE-US:

-

Contrast-enhanced US

References

Takahashi H, Sawai H, Matsuo Y, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver in a patient with colon cancer: report of two cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:25.

Machida T, Takahashi T, Itoh T, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5403–7.

Ishida M, Nakahara T, Mochizuki Y, et al. Hepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia in a patient with primary biliary cirrhosis. World J Hepatol. 2010;2:387–91.

Zen Y, Fujii T, Nakanuma Y. Hepatic pseudolymphoma: a clinicopathological study of five cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:244–50.

Matsumoto N, Ogawa M, Kawabata M, et al. Pseudolymphoma of the liver: Sonographic findings and review of the literature. J Clin Ultrasound. 2007;35:284–8.

Park HS, Jang KY, Kim YK, et al. Histiocyte-rich reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver: unusual morphologic features. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23:156–60.

Okada T, Mibayashi H, Hasatani K, et al. Pseudolymphoma of the liver associated with primary biliary cirrhosis: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4587–92.

Hayashi M, Yonetani N, Hirokawa F, et al. An operative case of hepatic pseudolymphoma difficult to differentiate from primary hepatic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:3.

Marchetti C, Manci N, Di Maurizio M, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of liver mimicking late ovarian cancer recurrence: case report and literature review. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16:714–7.

Amer A, Mafeld S, Saeed D, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver and pancreas. A report of two cases and a comprehensive review of the literature. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:e71-80.

Song JS, Yu HC, Moon WS. Hepatic mass with lymphadenopathy in a B viral hepatitis patient. Liver Int. 2014;34: e324.

Lv A, Liu W, Qian HG, et al. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma: incidental finding of two cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5863–9.

Kwon YK, Jha RC, Etesami K, et al. Pseudolymphoma (reactive lymphoid hyperplasia) of the liver: A clinical challenge. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2696–702.

Calvo J, Carbonell N, Scatton O, et al. Hepatic nodular lymphoid lesion with increased IgG4-positive plasma cells associated with primary biliary cirrhosis: a report of two cases. Virchows Arch. 2015;467:613–7.

Yang CT, Liu KL, Lin MC, et al. Pseudolymphoma of the liver: Report of a case and review of the literature. Asian J Surg. 2017;40:74–80.

Suzumura K, Hatano E, Okada T, et al. Hepatic Pseudolymphoma with fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on positron emission tomography. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2017;10:826–35.

Seitter S, Goodman ZD, Friedman TM, et al. (2018) Intrahepatic Reactive Lymphoid Hyperplasia: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Surg 9264251.

Kunimoto H, Morihara D, Nakane SI, et al. Hepatic Pseudolymphoma with an occult hepatitis B virus infection. Intern Med. 2018;57:223–30.

Zheng YC, Xie FC, Kang K, et al. Hepatobiliary case report and literature review of hepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia with positive anti-smooth muscle antibody and anti-nuclear antibody tests. Transl Cancer Res. 2019;8:1001–5.

Inoue M, Tanemura M, Yuba T, et al. A case of hepatic pseudolymphoma in a patient with primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7:1863–9.

Bai Y, Liang W. Potential value of apparent diffusion coefficient in the evaluation of hepatic pseudolymphoma. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2019;9:340–5.

Kobayashi A, Oda T, Fukunaga K, et al. MR imaging of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1282–5.

Dong C, Lu Q, Wang W, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound features of hepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia correlation with histopathologic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:2379–88.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Human/animal Rights

Since this case is a case report, we consider that it is a report of the results of practical medical care and is not included in the ‘medical research involving human subject’ covered by the Declaration of Helsinki. We are careful about the ethical aspects of our patient.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was given to the patient during examination and treatment.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsuyama, S., Fukuda, A., Omatsu, R. et al. A case of hepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia: the review of 23 cases from the literatures. Clin J Gastroenterol 16, 877–883 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-023-01844-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-023-01844-4